Introduction and background

Reference

1.1

On 17 March 2016, the Senate referred the following matter to the

Environment and Communications References Committee (the committee) for inquiry

and report by 30 May 2016:

The response to, and lessons learnt from, recent fires in

remote Tasmanian wilderness affecting the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage

Area, with particular reference to:

- the impact of global warming on fire frequency and

magnitude;

- the

availability and provisions of financial, human and mechanical resources;

- the adequacy of fire assessment and modelling

capacity;

- Australia's

obligations as State Party to the World Heritage Convention;

- world best practice in remote area fire management;

and

- any related matter.[1]

1.2

On 8 May 2016, the Governor–General issued a proclamation dissolving the

Senate and the House of Representatives on 9 May 2016 for a general election on

2 July 2016. As a result of the dissolution of the Senate, the committee

ceased to exist and the inquiry lapsed.

1.3

The 45th Parliament commenced on 30 August 2016 and the

committee was appointed on 31 August 2016.[2]

On 13 September 2016, the Senate agreed to the committee's recommendation that the

inquiry be re-adopted with the terms of reference unchanged and with a

reporting date of 1 December 2016. The Senate agreed also that the committee

have the power to consider and use the records of the Environment and

Communications References Committee appointed in the 44th Parliament.[3]

1.4

The reporting date was subsequently extended to 8 December 2016.[4]

Conduct of the inquiry, acknowledgement and note on references

1.5

In accordance with its usual practice, the Environment and

Communications References Committee of the 44th Parliament advertised

the inquiry on its webpage, and wrote to organisations and individuals, inviting

submissions by 15 April 2016. The committee continued to receive

submissions after this date. In total, the committee received 34 submissions, which

are published on the committee's website and listed at Appendix 1.

1.6

In addition to the published submissions, the committee received nine

form letters in relation to the inquiry. These were available to the committee

throughout the inquiry but the form letters were not published as submissions.

1.7

The committee held public hearings in Canberra on 1 November 2016 and

Launceston on 2 November 2016. A list of witnesses who appeared at the hearings

is at Appendix 2 and the evidence received by the committee is available on the

committee's website.

1.8

The committee thanks those organisations, individuals, departments and

agencies that contributed to the inquiry.

1.9

All references in this report are to the proof Hansard and page

numbers may vary between the proof and the official Hansard.

Structure of the report

1.10

This chapter outlines the history and effect of the bushfires that

occurred in the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA) in early 2016.

The chapter particularly notes the vegetation types affected by the fires.

1.11

The following chapters examine:

-

the impact of climate change on fire frequency and magnitude in the

TWWHA (chapter two);

-

the adequacy of the TWWHA's fire assessment and modelling

capacity (chapter three);

-

the financial, human and mechanical resources that were available

and provided for the bushfires in the TWWHA (chapter four); and

-

Australia's obligations under the Convention Concerning the

Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage and world best practice in

remote area fire management (chapter five).

Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area

1.12

The TWWHA covers approximately 1.6 million hectares, occupying almost

one-quarter of Tasmania and encompassing four national parks.

Figure 1.1: Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area

Source:

Parliamentary Library

1.13

The TWWHA is one of the largest temperate natural areas in the southern

hemisphere and is recognised as a World Heritage property for its Outstanding

Universal Value (OUV). It contains significant natural and cultural heritage,

including a wide range of plant communities (flora). Two‑thirds of

Tasmania's endemic higher plant species occur only in the TWWHA, and many

species provide living evidence of the Gondwanan origin of the Tasmanian flora.

Some species are representative of plant communities that once dominated

mainland Australia.[5]

1.14

The Parks and Wildlife Service, Tasmania (PWS) describes the TWWHA as

'the Australian stronghold of cool temperate rainforest'. Some vegetation

species in these forests date back over 60 million years and were once dominant

components of the vegetation across the Australian continent (before the

arrival of the eucalypts and acacias that now dominate the Australian flora). The

ancestors of many rainforest species—such as myrtle-beech, native plum and

leatherwood—evolved on the ancient continent of Gondwana. Many rainforest

species are extremely fire sensitive and can take 400 years or more, in the

absence of any further fires, to recover to their former glory after fire.[6]

1.15

According to the PWS, the TWWHA also hosts 'the most extensive and

pristine areas of alpine vegetation in Australia'. The dominant species are

shrubs, rather than the tussock grass and herb-dominant communities of the mainland

Australian Alps. About 60 per cent of the alpine flora is endemic to Tasmania. These

include such species as cushion plants, scoparia and Tasmania's only native

deciduous species, the deciduous beech. This alpine environment is extremely

fragile and susceptible to damage from fire.[7]

1.16

Most of Tasmania's unique conifers occur within the TWWHA: the second

longest lived organism in the world, the Huon pine; and the sole

representatives of the family Taxodiaceae to be found in the southern

hemisphere, the endemic King Billy pine (Athrotaxis selaginoides), the Pencil

Pine (Athrotaxis cuppressoides) and their natural hybrid, Athrotaxis laxifolia.

Like rainforest species, these conifers are highly susceptible to fire and in

some areas, extensive stands of dead 'stags' bear testimony to the ravages of

previous fires. Some species will never recover from burning.[8]

1.17

Moorlands are found throughout the TWWHA, with the sedge (buttongrass)

being the dominant species. The buttongrass moorlands contain over 150

vascular plant species, a third of which are endemic to Tasmania. Buttongrass

moorlands have a high frequency of fire and as a result, the acidic peat soil in

which they grow is among the most nutrient poor in the world.[9]

1.18

The TWWHA also provides secure habitats for some of the most unique

animals (fauna) in the world, as well as endangered species. Tasmania

and the TWWHA have a high proportion of endemic fauna, including five species

of mammal. Over half of the mammal species are a distinct subspecies from their

mainland counterparts. The TWWHA is also home to the three largest carnivorous

marsupials in the world: the Tasmanian devil; the spotted-tail quoll; and

eastern quoll. Endangered species within the TWWHA include species that have

recently become extinct or threatened on the mainland, and rare and threatened

species within Tasmania—such as the orange‑bellied parrot and the white

goshawk.[10]

1.19

In addition to its flora and fauna, the TWWHA is recognised for its

heritage values. These include: some of the richest and best preserved

Indigenous sites in Australia dating back around 45000 years; an 'outstanding'

example of one of the most significant features of world population movement in

the 18th and 19th centuries (the Macquarie Harbour

Historic Site); a profusion of complex and well‑exposed geological

features; and the most significant and extensive glacially modified landscapes

in Australia.[11]

1.20

Further, the TWWHA is important to Tasmania's culture, identity and

economy.[12]

For example, in 2008 a report commissioned by the (then) Department of the

Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts estimated that Tasmania's World Heritage

Areas contributed $721.8 million in annual direct and indirect state output or

business turnover, $313.5 million in annual direct and indirect state value

added, and 5372 direct and indirect state jobs.[13]

The 2016 bushfires and their estimated impact on the TWWHA

1.21

Bushfires are a part of Australia's natural environment. Compared to the

mainland, Tasmania has relatively infrequent fire weather and high intensity bushfires.

However, these fires can occur throughout the fire season (December to March).[14]

1.22

In January to February 2016, Tasmania experienced a series of dry

lightning strikes (commencing on 13 January). Fire authorities responded to

2350 incidents, including 639 vegetation fires. Of these fires, eighteen affected

the TWWHA, burning out approximately 19 936 ha (1.3 per cent).[15]

The majority of the burnt area was at Lake Mackenzie (13 822 ha), Mt

Cullen or Gordon River Road (3520 ha), and Maxwell River South (1389 ha).[16]

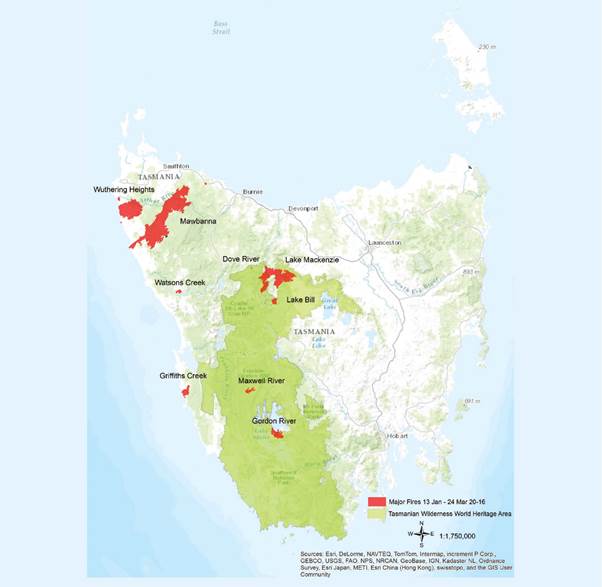

Figure 1.2: Major fires in Tasmania, 13 January to 24

March 2016

1.23

According to the Tasmanian Government, the majority of the burnt area

was composed of vegetation types and fauna that are adapted, or resilient, to

the effects of fire, and are therefore likely to recover to something similar

to their original state.[17]

Vegetation with high ecological

value

1.24

The Tasmanian Government identified the Mersey Forest Complex fires on

the alpine and sub-alpine vegetation around Lake Mackenzie as having the most

significant potential impact to vegetation values in the TWWHA:

The most significant flora value affected is Pencil Pine (Athrotaxis

cupressoides). This species is an iconic example of Gondwanic legacy in the

TWWHA, identified under World Heritage Criteria (ix). It also contributes to

the aesthetic importance of the alpine landscapes of the TWWHA identified under

World Heritage Criteria (vii). The recovery of cushion moorlands, various

alpine heathlands and sedgelands and alpine sphagnum peatlands will be

dependent on the fire intensity and degree of organic soil loss.[18]

1.25

Pencil Pine is classified as a 'threatened native vegetation community'

under the Nature Conservation Act 2002 (Tas).[19]

An estimated 141 ha of Pencil Pine forest and woodland are potentially impacted

by the bushfires, representing 'approximately 0.6% of the mapped distribution

of this species'.[20]

Figure 1.3: Aftermath of bushfires, Lake Mackenzie

Source: Rob Blakers, Submission 21, p. 9.

1.26

The fires are expected also to have affected geoconservation features (organic

and mineral soils, karst and fluvial systems, wetland peats, cushion moors and

sphagnum bogs).[21]

Some of these—organic soils and karst systems—are recognised as part of the OUV

of the TWWHA.[22]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page