CHAPTER 2

Key Issues

2.1

The ABF Bill and the ABF Amendment Bill raise quite distinct issues. It

follows that this chapter will examine each of the bills separately.

The ABF Bill

2.2

Submissions to the inquiry identified a number of key issues affecting the

ABF Bill. These issues related to the provisions dealing with directions, oaths

and affirmations, resignation from and termination of employment, alcohol and

drug tests, and secrecy.

Directions

2.3

As noted in chapter 1, the ABF Bill empowers the minister, the secretary

and the ABF Commissioner to give binding directions. Some submissions have

argued that the ABF Bill allows for a dangerous lack of accountability,

providing the minister and the ABF Commissioner with open‑ended powers.[1]

However, the joint submission of the department and customs explained that the

ABF Bill is substantively based on the Customs Administration Act 1985

(Cth) (CA Act) and, as such, the majority of the provisions in the ABF Bill,

including those related to directions, have been made 'subject to parliamentary

scrutiny on various occasions in the past'.[2]

For example, the provision allowing the minister to direct the ABF Commissioner

on the policies and priorities to be pursued and then to ensure that a copy of

the direction is laid before each House of the Parliament within 15 sitting

days correlates to section 4A of the CA Act.[3]

The joint submission also stated that the minister's power to direct the ABF Commissioner

would be consistent with the direct accountability of the ABF Commissioner

to the minister and, furthermore, the minister would remain bound by section 19

of the Public Service Act 1999 (Cth), limiting the minister's capacity

to make directions on breaches of the APS Code of Conduct and other individual

employment matters.[4]

2.4

Some submitters claimed that, as directions of the secretary and the ABF

Commissioner would be binding, IBP workers, including contractors, would be compelled

to adhere to a directive, irrespective of individual conscience, organisational

code of conduct or perceived duty of care.[5]

2.5

The joint submission of the department and customs explained that:

Immigration and Border Protection workers will make decisions

and exercise powers that affect the safety, rights and freedoms of individuals

(sometimes significantly and irrevocably) as well as trade and commerce in

Australia. They will hold a privileged place at the border and in the

community, with access to secure environments and law enforcement databases.

They will also exercise significant enforcement powers under the Customs Act,

the Migration Act, the Maritime Powers Act and other Commonwealth laws. The

community and Government trust Immigration and Border Protection workers to

exercise these powers reasonably, lawfully, impartially and professionally...It

is imperative that the ABF be established as a disciplined and professional

workforce that can be flexibly deployed in line with changing requirements and

risks.[6]

2.6

The department and customs clarified that the provisions that would empower

the secretary and the ABF Commissioner to make binding written directions on

the administration and control of the department and the ABF, respectively, were

broadly modelled on section 4B of the CA Act.[7]

2.7

The Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU) and the Asylum Seeker

Resource Centre (ASRC) in-principle did not have an objection to the specific

legislative power to issue directions requiring essential qualifications but

both criticised the lack of specificity as to how and when essential qualifications

could be introduced.[8]

The ASRC did acknowledge that the Explanatory Memorandum to the ABF Bill

contemplates that IBP workers may need to undergo psychometric and resilience

training to ensure that they have the 'emotional and mental disposition suitable

for the performance of certain duties'.[9]

The Law Council of Australia (LCA) stated that the person making a direction on

essential qualifications should ensure that they are consistent with relevant

obligations not just under the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth),

but also the Age Discrimination Act 2004 (Cth), the Racial

Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) and the Sex Discrimination Act 1984

(Cth).[10]

2.8

The department and customs stated:

Establishing a specific legislative power to issue such

directions will assist the department to ensure the workforce has the necessary

skills and attributes relevant to the roles being performed within the

integrated department and enable the highest standards of operational

effectiveness and professional integrity to be achieved.[11]

2.9

The CPSU challenged the need for a specific legislative power to allow

the secretary or the ABF Commissioner to make directions on mandatory

reporting. The CPSU submitted:

The deployment of these powers will produce a work

environment that is lacking in trust; a poor workplace culture that is likely

to drive behaviours that are not conducive to uncovering the very behaviour

that this legislation aims to prevent. Efforts to promote teamwork and bonds

necessary between workers performing difficult and dangerous duties and their

management will be undermined by this requirement. The introduction of these

powers will only serve to make potentially criminal or corrupt elements within

the Department more secretive and harder to detect by anyone.[12]

2.10

By contrast, the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity

(ACLEI) stated:

Integrity measures, such as Mandatory Reporting and

Organisational Suitability Assessments, help to mitigate the likelihood of

staff members exercising inappropriate discretion about what to report.

To promote procedural fairness and accountability...it is

appropriate and advisable for the Secretary and the ABF Commissioner to have a

legislative basis for issuing binding directions relating to these integrity

controls.[13]

2.11

The Explanatory Memorandum to the ABF Bill notes that the proposed

mandatory reporting powers would be consistent with subsection 4B(2) of the Customs

Administration Act 1985 (Cth). The Explanatory Memorandum reasons that:

The intention of the power for the ABF Commissioner to impose

mandatory reporting requirements is to support the identification and

investigation of potential criminal behaviour or corruption that is likely

affect the operation or reputation of the Department...Given the type of work

that IBP workers perform and the importance of maintaining a high integrity

workplace, mandatory reporting of such conduct or activities is considered a

useful preventative, deterrence and response tool.[14]

Oaths and affirmations

2.12

A few submissions commented on the requirement for the ABF Commissioner

to make and subscribe to an oath before beginning to discharge his or her

duties. The submissions argued that the particular form of the oath has not

been specified as it would be prescribed by the relevant rules.[15]

The LCA and the Combined Refugee Action Group (CRAG) also questioned the need

for a provision which would allow the ABF Commissioner to request an IBP worker

to make and subscribe to an oath or affirmation, respectively arguing that

junior clerks of the department and contractors should not be made subject to

this provision.[16]

Moreover, the Australian Public Service Commissioner recommended that the

content of any such oath or affirmation should be consistent with the APS

Values, Employment Principles and Code of Conduct.[17]

2.13

The department and customs commented that the requirement to make and

subscribe to an oath or affirmation would be:

...critical in an

environment where significant enforcement powers are being exercised

and there is community

expectation of the highest standards

of integrity.

The ABF Commissioner will have the same standing

as the Chief of the Defence Force

and the Australian Federal

Police Commissioner. These

offices have oaths or affirmations attached to them. It

is therefore appropriate that the ABF Commissioner should also be required to make and subscribe an oath or affirmation and that he or she should be able to request certain

ABF officers to make

and subscribe an oath or affirmation as well. It is anticipated that the oath or affirmation given by

these officers would be similar to the kind prescribed for certain Australian Federal Police officers under section 36 of

the Australian Federal Police Act 1979

(Cth).[18]

2.14

The committee notes that ABF Bill would only empower the ABF

Commissioner to request an IBP worker in the ABF or a person whose

services were made available to or who was performing services for the ABF, not

junior clerks of the department, to make and subscribe to an oath or

affirmation.[19]

The Explanatory Memorandum to the ABF Bill states:

Requiring employees responsible for exercising significant

enforcement powers to subscribe to behaviour that upholds public service

professionalism and ethics is essential to safeguard the reputation of the

Department and the safety of the general public. The oath or affirmation is

intended to be similar to the kind prescribed for certain AFP officers in the

AFP Regulations.[20]

Resignation and termination

2.15

The CPSU challenged both the resignation and termination powers proposed

by the ABF Bill arguing that they were superfluous, given that existing powers

under the Australian Public Service Act 1999 (Cth) would be sufficient

to secure the integrity of the workplace.[21]

Other submitters, including the LCA, submitted concerns relating to the

proposed provisions limiting the extent to which an employee could seek

remedies under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) after a declaration is made

by the secretary or the ABF Commissioner confirming termination of employment on

grounds of serious misconduct.[22]

The CPSU and LCA argued that the proposed termination provision and associated

declaration power would curtail an employee's right to natural justice by

taking away any appeal mechanism to examine the merits of the decision to

terminate the employment and removing the defence of reasonable excuse.[23]

The CPSU, LCA and the Refugee Council of Australia (RCOA) came to the same

conclusion: that the existing provisions in the Public Service Act 1999

(Cth) that apply to serious misconduct are adequate to ensure the integrity of

the immigration and border protection workforce as the Fair Work Commission

would not overturn a termination decision that had merit; the Fair Work

Commission would only question a case where the alleged misconduct was found not

to have occurred, where it occurred but the employee had a reasonable excuse or

where the misconduct was not serious enough to warrant dismissal.[24]

2.16

The department and customs justified the proposed resignation powers by

stating:

Under current provisions of the Public Service Act, an

investigation into a breach of the APS Code of Conduct can continue after an

employee has resigned but there is no provision to apply a sanction to the

person as he or she is no longer an employee. This confines the ability of the

department to address instances of serious misconduct and corrupt conduct. The

proposed power to delay the date of effect of a person's resignation is an

appropriate measure to address this issue as it will permit any investigation

to be concluded, and where warranted, sanctions to be applied. This is an

important demonstration to staff, the Government and the wider community of the

department's commitment to professionalism and high standards of integrity and

its unwillingness to tolerate conduct that threatens these values.[25]

2.17

The department and customs also explained that the termination provision

and associated declaration power would be an essential part of securing the

integrity of the department as they would provide the secretary and the ABF

Commissioner an ability to quickly and decisively remove an employee, thereby

removing any possibility that highly sensitive information could be exposed.

Furthermore, the efficient termination of an employment contract would avoid mixed

signals being sent to other employees and the general public about the

department's level of tolerance for serious misconduct.[26]

The LCA and the joint submission of the department and customs highlighted that

the termination and declaration-making powers of the secretary and the ABF

Commissioner would not affect an employee's right of review under the Administrative

Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth).[27]

The joint submission also noted that general protections claims under the Fair

Work Act 2009 (Cth) and claims under anti-discrimination legislation would

not be affected by the proposed provisions, adding that:

This provision mirrors the declaration provision currently

applicable to ACBPS workers under section 15A of the Customs Administration Act

and it is proposed to replicate its effect across the integrated department.

Section 15A of the Customs Administration Act was modelled on the declaration

of serious misconduct provisions applicable to Australian Crime Commission and

Australian Federal Police staff. The provision was introduced in 2012 as part

of a series of measures designed to increase the resistance of Commonwealth law

enforcement agencies to corruption and to enhance the range of tools available

to agencies to respond to suspected corruption. The declaration

provisions were subject to parliamentary scrutiny at that time and the

Committee recommended passage of the provisions in their entirety.[28]

Alcohol and drug tests

2.18

Although the CPSU had no objections to the concept of drug and alcohol

testing, the CPSU stated that it was concerned with the way in which the ABF

Bill proposed to introduce the testing. The CPSU contended that the proposed universal

drug and alcohol testing regime may act to undermine employee trust and the

testing regime may be abused by management, opening up the possibility that

certain employees could be unfairly targeted for tests or harassed by repeated

requests for tests. Additionally, the CPSU was not convinced that the benefit

of alcohol and drug testing certain employees, such as those in administrative

roles, could justify the cost.[29]

2.19

ACLEI supported the proposed regime contending that passive integrity

measures are not sufficient to address the emerging threat of corruption‑enabled

border crime. ACLEI cited operational experience that showed that mandatory

reporting and drug testing have provided an effective deterrent to corrupt

behaviour and a general rise in professional standards and threat awareness.

ACLEI, through recent investigations, observed that law enforcement staff had

used illicit drugs, but considered this behaviour to be private and separate

from their law enforcement roles. ACLEI stressed that:

Those investigated...failed to realise that, by using illicit

drugs, they exposed themselves to considerable risk of compromise, including

possible exposure to blackmail in return for keeping their drug use hidden.

Several had also failed to recognise the potential value to organised crime

groups of the information each held as a result of their official duties...Accordingly,

having regard to the sensitive functions undertaken by DIBP employees...broad-based

drug testing of employees is an important corruption deterrence and detection

measure.[30]

2.20

The department and customs reiterated that the proposed alcohol and drug

testing regime would help increase the department's capacity to better resist

corruption and ensure a safer working environment. The joint submission

explained:

Where Immigration and Border Protection workers are privately

participating in the use and possession of illicit drugs, this behaviour is in

direct conflict with their official duties and may enhance vulnerability to

corruption. Corruption can have a significant detrimental effect on the ability

to enforce the law, and the introduction of a drug and alcohol testing regime

will provide another tool to detect corruption and misconduct across the

broader department...The Government also considers that implementation of drug

and alcohol testing is an appropriate response to the significant consequences

that could arise from Immigration and Border Protection workers acting under

the influence of drugs or alcohol in the course of their duties.[31]

2.21

The joint submission indicated that existing drug and alcohol screening

arrangements have proven to operate effectively for customs, the Australian

Federal Police and the Australian Crime Commission. As with the existing

testing arrangements, the department and customs noted an intention that the

testing would be conducted in line with the relevant Australian standards and

procedures, helping to minimise any privacy concerns.[32]

Secrecy and disclosure

2.22

Several submissions were critical of the proposed secrecy and disclosure

provisions in Part 6 of the ABF Bill. The submissions argued that the

provisions essentially criminalise any whistleblowing by IBP workers that does

not fall within an exception, questioning whether the provisions would act to

limit the public disclosure of human rights abuses or breaches of law.[33]

The ASRC highlighted that the evidentiary burden of proving that whistleblowing

falls within an exception would fall on the accused.[34]

The LCA recommended that:

The secrecy offences should include an express requirement

that, for an offence to be committed, the unauthorised disclosure caused, or

was likely or intended to cause, harm to an identified essential public

interest.[35]

2.23

The committee takes the view that such an express requirement is not

necessary as paragraph 42(2)(c) of the ABF Bill already provides an exception

where 'the making of the record or disclosure is required or authorised by or

under a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory'.[36]

The term 'a law of the Commonwealth' includes the Public Interest Disclosure

Act 2013 (Cth) that facilitates the 'disclosure and investigation of

wrongdoing and maladministration in the Commonwealth public sector'.[37]

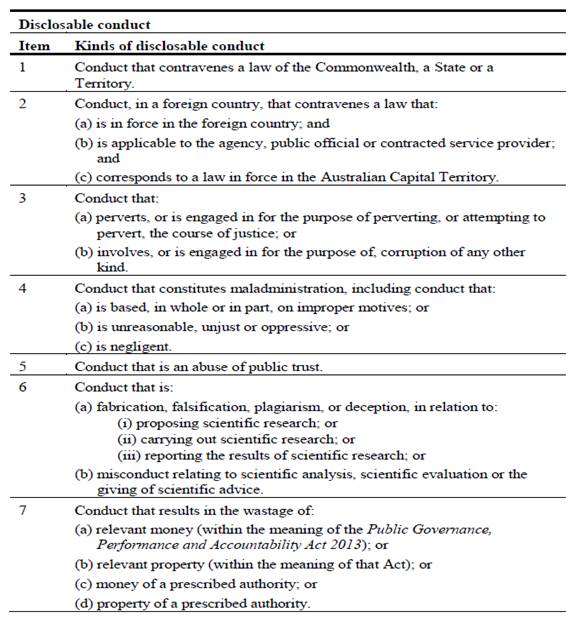

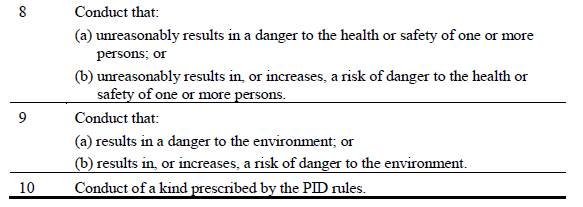

Section 29 of the PID Act defines 'disclosable conduct' as conduct by an

agency, public official or contracted service provider that falls under one or

more items in the following table:

2.24

ACLEI made the point that under clause 43 of the ABF Bill potential

whistleblowers and potential witnesses could also provide any relevant

information directly to ACLEI without the need to seek authorisation, avoiding

the onus of proving a defence.[38]

2.25

The department and customs advised that the proposed secrecy and disclosure

provisions were modelled on section 16 of the Customs Administration Act

1985 (Cth), and adapted to ensure that the new provisions could operate

efficiently and effectively within the context of the broader functions of the

department and with other information protection and disclosure provisions in

related legislation. The joint submission reasoned that:

The proposed application of these information protection

provisions to the integrated department will enable the department to regulate

the disclosure of sensitive information in a way that is appropriate and

measured. This framework will also provide partner agencies and stakeholders,

including industry and international law enforcement and intelligence partners,

with assurances that information provided to the department can only be

disclosed in the manners contemplated by the information protection provisions.

Similar information protection and disclosure provisions also

exist in comparable legislation such as the Australian Federal Police Act 1979,

the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979, the Income

Tax Assessment Act 1997 and the Australian Crime Commission Act 2002.[39]

The ABF Amendment Bill

2.26

The key issues pertaining to the ABF Amendment Bill may be broken down

into three separate categories, being issues relating to the proposed

amendments to the WHS Act, issues relating to the proposed extension of ACLEI's

jurisdiction to investigate the whole department, and issues relating to the

proposed consequential amendments to other Acts. Each of these categories will

be examined in turn.

Proposed amendments to the WHS Act

2.27

The RCOA submitted that the proposed provisions of the ABF Amendment Bill

that would permit the suspension of specified sections of the WHS Act are

unnecessary, arguing that the WHS Act 'already offers significant flexibility

in responding to the varied work health and safety issues which may arise in a

wide range of workplaces'.[40]

2.28

The statutory work health and safety regulator, Comcare, noted

declaration powers similar to those proposed in Schedule 4 of the ABF Amendment

Bill are already available to certain agencies under the WHS Act. Comcare cited

that the consultation and approval requirements proposed would provide

sufficient safeguards and submitted that it could not foresee any issues with

its operations or the regulation of work health and safety in the ABF.[41]

2.29

The department and customs added that:

The proposed amendments to the WHS Act appropriately

recognise the risks faced by Australian Border Force officers in protecting

Australia's national security and defence. The declarations are not intended to

weaken protections for workers, or remove any obligations for the department as

an employer to ensure a safe workplace. In contrast, they can only be put in place

where necessary, and with the required consultations and Ministerial approvals,

to remove any uncertainty for ABF workers regarding their obligations under the

WHS Act.

It is intended that ABF officers will continue to undertake

risk assessments, follow instructions and be well-trained and equipped for the

performance of all duties. At all times, the department will prioritise the

health and safety of its workers and promote the objectives of the WHS Act to

the greatest extent consistent with maintenance of Australia's national

security and defence.[42]

Proposed extension of ACLEI's

jurisdiction to the whole department

2.30

Both the department and customs and ACLEI supported the proposed

expansion of ACLEI's jurisdiction, which would allow it to investigate serious

and systemic corruption issues throughout the department, not just the ABF. As

noted by the department and customs:

...Immigration and Border Protection workers will have access

to secure environments, protected systems and sensitive information which are

valuable and therefore attract a heightened integrity risk...The consequences of

any corruption in the department, including in the ABF, would pose a

significant threat to the integrity of the border and Australia's national

security...These provisions will ensure the Integrity Commissioner's unhindered

ability to investigate suspected law enforcement related corrupt activity

across the integrated department regardless of the specific role, location or

job title of the individual worker.[43]

2.31

ACLEI reiterated these points, adding:

...an emerging risk seen in a number of recent ACLEI

investigations is that "back office" staff—administrative and other

support staff who also have access to sensitive information—may be as

vulnerable to compromise as operational staff. In addition, since they may be

less prepared to respond to improper approaches, support staff may be more

exposed to risk than was previously considered to be the case...A whole‑of‑agency

approach also reduces the potential for disputation or legal contest over the

scope of ACLEI’s jurisdiction.[44]

Proposed consequential amendments

to other Acts

2.32

The department and customs explained that the proposed amendments in Schedules

2, 5, 6 and 7 of the ABF Amendment Bill were designed to provide transitional

provisions and consequential arrangements to ensure continuity of operations

and information and intelligence sharing between relevant agencies following the

repeal of the Customs Administration Act 1985 (Cth).[45]

2.33

However, the LCA argued that some of these provisions dealing with the

expansion of powers from customs to the department could be problematic. The

LCA challenged the need to expand the controlled operations scheme and the

assumed identities scheme of Part 1AB and 1AC Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) to

the department, recommending that it should be limited to IBP workers in the

ABF. Similarly, the LCA argued that only authorised IBP workers in the ABF, not

all authorised IBP workers, should be able to apply for a freezing order under

the Proceeds of Crimes Act 2002 (Cth).[46]

The LCA also challenged the proposed amendments to the Telecommunications

(Interception and Access) Act 1979 (Cth), recommending that only the ABF

and not the broader department should be able to obtain a stored communications

warrant. The LCA submitted:

Given the intrusive nature of stored communications warrants

and their ability to reveal sensitive personal information, the Law Council

considers that it is inappropriate to permit the broader IBP Department, rather

than just the ABF, access to stored communications warrants, unless there is a

demonstrated need to do so.[47]

2.34

Finally, the LCA noted that the amendments in Schedule 5 of the ABF

Amendment Bill would expand integrity testing to the department as a whole and

this would allow ACLEI to apply for a warrant to use surveillance devices under

the Surveillances Devices Act 2004 (Cth) for the purposes of that

testing. LCA submitted that these provisions should only apply to operational

staff.

2.35

The minister, in his second reading speech, explained that controlled

operations scheme and the assumed identities scheme of Part 1AB and 1AC of the Crimes

Act 1914 (Cth) were important provisions. The minister stated:

In its 2013 report into organised crime in Australia, the

Australian Crime Commission details the significant impact serious and

organised crime has on the everyday lives of Australians. The commission

conservatively estimates organised crime costs Australia $15 billion annually

and notes the ability for such crime to undermine our border integrity, erode

the confidence in institutions and law enforcement agencies and damage our

prosperity and regional stability. This form of crime reaches across borders

and can include trafficking in drugs or in people, corruption, and money

laundering.

With the increasing threat of serious organised and

transnational crime, it is vitally important that Australia's border

arrangements continue to be able to operate with relevant powers and

protections to conduct operations that counter these threats. Accordingly, the

bill substitutes the Department of Immigration and Border Protection for the

Australian Customs and Border Protection Service as the primary agency with

overarching responsibility for protecting our borders. It therefore ensures

these provisions will continue to apply to officers in my department when the

new organisational arrangements are in place.[48]

2.36

In its submission, ACLEI expressed support for integrity testing, by

stating:

Integrity testing is a specific method of investigating

suspected corrupt conduct, whereby an officer is placed in an observed

situation that is designed to test in a fair way whether he or she will respond

in a manner that is illegal, unethical or otherwise in contravention of the

required standard of integrity. The consequences of failing an integrity test

can include disciplinary action, termination of employment or criminal charges.

The inclusion of this measure reflects and responds to

ACLEI’s experience of the challenges involved in investigating corrupt

conduct. It does so in a way which ensures accountability, protects the rights

and reputations of individuals, and provides appropriate legal protection for

officers who conduct authorised integrity tests.

Having regard to corruption enabled border crime risks, as

well as the desirability of corruption investigation and deterrence measures

being able to be applied across a jurisdiction, ACLEI supports the extension of

integrity testing to DIBP.[49]

2.37

The committee agrees with ACLEI's position on integrity testing and

accepts that the controlled operations scheme and the assumed identities

schemes should be expanded to the department as a whole.

2.38

Furthermore, the committee takes the view that, as the amended Proceeds

of Crimes Act 2002 (Cth) would only allow authorised officers of the

department to apply for a freezing order, the proposed amendments do not

drastically change the status quo. Following the same reasoning, the committee

notes that the amended Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979

(Cth) would not change the requirement that a certifying officer must be

authorised to apply for a stored communication warrant. The committee cites the

reasoning in the Explanatory Memorandum to the ABF Amendment Bill, which states

that the amendments to the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act

1979 (Cth):

...will enable the continued operation capability of key activities

currently performed by the ACBPS, which will in the future be undertaken within

the integrated Department.[50]

Recommendation 1

2.39

The committee recommends that the Senate pass the Australian Border

Force Bill 2015 and the Customs and Other Legislation Amendment (Australian

Border Force) Bill 2015.

Senator

Barry O'Sullivan

Chair

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page