Chapter 3 - Australia's

current account – key issues

At some point, net

external liabilities to GDP have to stop rising. They cannot go on going up

forever, but it is far from obvious how much further net external liabilities

to GDP could rise.[18]

Background

3.1

This section of the report explores a number of key

issues relating to Australia's

current account which were raised in submissions to the Inquiry, and discussed

during the Round Table held in Canberra

on 15 August 2005.

3.2

The economists who participated in the Round Table

were:

-

Professor Ross Garnaut, Professor of Economics,

Division of Economics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian

National University;

-

Dr David Gruen, Chief Adviser (Domestic),

Macroeconomic Group, Department of the Treasury;

-

Mr John Hawkins, Manager, Domestic Economy

Division, Department of the Treasury;

-

Mr Anthony Pearson, Head of Australian

Economics, ANZ Banking Group;

-

Mr Michael Potter, Director of Economics and

Taxation, Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry; and

-

Dr Richard Simes, Vice President, CRA

International (appearing in a private capacity).

3.3

Evidence presented by Mr

Pat Conroy,

National Projects Officer of the Australian Manufacturing Workers Union (AMWU)

at the public hearing in Sydney

on 16 May 2005 was also

considered in the context of this chapter.

3.4

At the conclusion of the Round Table, the Chair invited

each participant to make concluding remarks.

The concluding remarks are set out in full in Appendix 4 to this report,

as they are a good summation of the views expressed.

3.5

The key issues which were considered during the Inquiry

are expressed as a series of questions in this chapter.

What has been driving the Current Account Deficit?

3.6

There was general agreement in the evidence received by

the Committee that the household sector has been the main driver behind the

Current Account Deficit (CAD) in recent years.[19]

3.7

Professor Garnaut

expressed it this way:

The biggest single cause of a large current account deficit is

the decline in household savings, which I think most economists ... would

attribute above all else, directly and indirectly, to the extraordinary wealth

effects of our housing boom, which is

large by our historical standards and large by world standards. It led

Australian households ... to think that they were very wealthy and very

comfortable, and that they could comfortably go through a period of higher

consumption expenditure and low, zero or negative savings ...[20]

3.8

Dr Gruen

also believes that the present CAD is attributable to the household sector. He

said:

In the last 25 years it is only in the last couple of years that

the household sector has run a savings-investment imbalance of the order of the

size of the current account. I think it is reasonable from that perspective to

say that it is the household sector where, if you like, you can explain why the

current account has been as large as it has recently. I think it is reasonable

to say that that is largely a consequence of savings-investments decisions by

the household sector.[21]

3.9

Likewise, Mr Conroy

identified households as the driver of economic growth in recent years:

The growth in household

debt has been the driver of Australia’s economic growth over the last eight years

and in particular the last two years.[22]

3.10

But Mr Pearson

said that he preferred to look at the CAD from a trade perspective. He attributes the present high CAD to an

'acceleration of import growth since 2001, particularly in volume terms, but in

particular there has been flatness in the volume of exports'. That meant a

widening trade deficit which fed into a high CAD. However, he considered that the breaking of

the drought would lift agricultural exports and higher prices for minerals and

energy can also be expected to lift exports.[23]

What is the outlook for Australia's

current account?

3.11

At the

Round Table discussion Dr Simes expressed the view that the average of the CAD is moving up to a new

and higher level. He said:

My assessment of the numbers is that, after some of the things

in the system work their way through, we are probably looking at the average of

the current account deficit to GDP increasing from around 4½ per cent to maybe

between five and six per cent.[24]

3.12

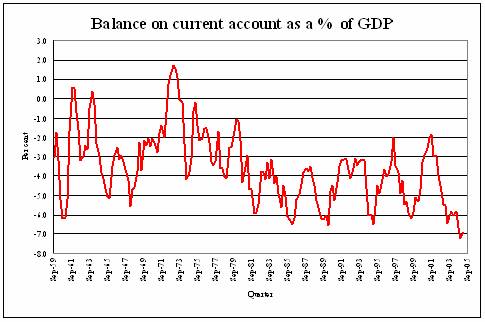

Figure 3.1 shows the wide fluctuations over the last 45

years in the balance of the current account when expressed as a percentage of

GDP. As discussed in Chapter 2, the

current account has been in continuous deficit since 1973 and the deficits

appear to be increasing in size, both in dollar terms and as a percentage of GDP.[25]

Figure 3.1: Balance on current account as a percentage of GDP

Sources: ABS, Balance of Payments and International

Investment Position (Cat. No. 5302.0) and National Income Expenditure and Product (Cat. No. 5206.0)

3.13

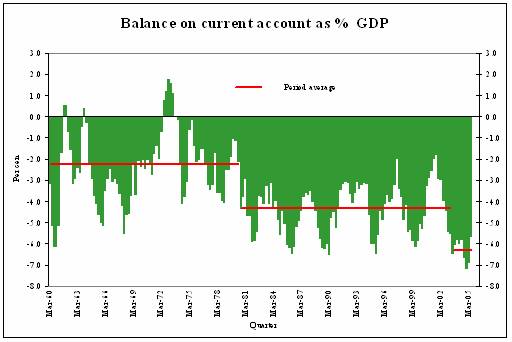

A way of looking for trends is to identify if there

have been periods which have involved a quantum shift. Figure 3.2 suggests that

since 1960 the CAD has experienced two periods involving quantum shifts, with a

possible third period starting in 2003.

Figure 3.2: Balance on current account as a

percentage of GDP, showing period averages

Source: ABS, Balance of

Payments and International Investment Position (Cat. No. 5302.0) and ABS, National

Income Expenditure and Product (Cat. No. 5206.0). Bars show quarterly results based on original

figures.

3.14

Figure 3.2 shows that in the period 1960 - 1980 the CAD

averaged 2.4 per cent of GDP. There was a quantum shift to a new level for the

period 1981 - 2002, during which the CAD averaged 4.4 per cent of GDP. Figure 3.2 speculates that in 2003 Australia

may have taken another quantum step up, to a period when the CAD could average

around 6 per cent of GDP per annum.

3.15

During the second 'step' period shown in Figure 3.2

(1981 - 2002) the quarterly CAD was less than the average of the previous

period in only two quarters - in the June 2001 quarter (2.0 per cent), and in

the September 2001 quarter (1.8 per cent).

All the other quarters in the second period recorded current account

deficits which were above the 2.4 per cent average for the 1960 - 1980 period.

3.16

There have been several periods since 1960 during which

the CAD has exceeded 5 per cent for more than three consecutive quarters. These periods were:

Table 3.1: Periods of consecutive quarters

when the CAD exceeded 5% of GDP.

|

Period |

Number

of consecutive quarters the CAD exceeded 5% of GDP |

|

June 1960 – March 1961 |

4 |

|

December 1981 – June 1982 |

3 |

|

June 1985 - September 1986 |

6 |

|

December 1988 - March 1990 |

6 |

|

September 1994 – June 1995 |

4 |

|

September 1998 - March 2000 |

7 |

|

December 2002 – present (June 2005) |

11 |

Source: ABS, Balance

of Payments and International Investment Position (Cat. No. 5302.0)

3.17

These periods of high CAD appear to be occurring more

frequently and for longer.

3.18

The CAD of 5.7 per cent in the June 2005 quarter means

that the CAD has now been over 5 per cent of GDP for eleven consecutive

quarters (including the new record of 7.2 per cent set in the December 2004

quarter). The average of the CAD for the last 11 quarters was about 6 per cent.[26]

3.19

Mr Conroy

opined that the recent current account deficits would have been higher except for

the record terms of trade. He said:

The only reason that the 2004 and 2005 current account deficits

have not attracted as much concern as the ones in the mid-80s is due to the

record high terms of trade. Had the terms of trade stayed at their 1990s average,

the external deficit would now be 10 per cent, not 6.75 per cent, of GDP ... These historic

terms of trade cannot last and serve to conceal the true nature of Australia’s external imbalance.[27]

3.20

Professor Garnaut

made a similar point when he said that the recent high levels of CAD would have

been even higher except for a fortuitous combination of events - Australia's

very high terms of trade and very low international interest rates. He said:

There are a couple of features of that big number [CAD of 7.2%]

... it has occurred at a time of historically extremely high terms of trade ... a

time of unusually low global interest rates so that the financing demands of

the large external liabilities are less severe than they would be in normal

times for international interest rates. If international interest rates were

near the average of the last 20 years, rather than historically extremely low,

then that would add possibly a couple of per cent to the current account

deficit.[28]

3.21

Dr Gruen

disagreed as to the level of risk posed by future increases in international

interest rates:

In terms of servicing the foreign debt, I do not think that

global interest rates are all that relevant. The ABS did a survey in 2001 of

the hedging practices of Australian companies. They have just redone this

survey and the results will be published later in the year. When the first

survey was done, the ABS was given the answer that 77 per cent of the value of

foreign currency denominated debt was hedged back to Australian dollars. That

is more than three-quarters. If you hedge foreign currency debt back to

Australian dollars, you effectively pay Australian interest rates. I do not

know the results of the more recent survey, but, if that is a reasonable

reflection of the situation as it is now, the servicing of Australia’s

foreign debt is largely in Australian interest rates, and a change in global

interest rates has a relatively small effect on that.[29]

3.22

Mr Hawkins

supported that assessment by Dr Gruen:

... while we have large net external liabilities to GDP, as had

some of the East Asian countries, we are much less vulnerable to a large

movement in the exchange rate, because, as David [Gruen] commented earlier, we

are not in a position where all our debt is in foreign currency and unhedged. A

significant amount of our debt is in Australian dollars and a significant

amount of the debt that is not is either hedged in financial markets or

naturally hedged through the export flows that companies which have borrowed

have.[30]

3.23

But Professor Garnaut

cautioned that currency hedging is not risk-free:

... I think we should not become too complacent about a high

proportion of our foreign debt being hedged against currency risk, because

there are specific terms to those hedging contracts and when they come to an

end they have to be recontracted. And if there is any deterioration in our

circumstances—in interest rates, perceptions of capacity to repay the debt of

Australian entities or currency risk—then that will affect the terms on which

the hedges are rolled over. So that can mean that a problem is phased in, if

things turn against us, but it does not mean to say that you avoid the problem

altogether.[31]

Is there a link between offshore borrowing and the current account?

3.24

Offshore borrowing by banks and other financial institutions

has increased in recent years.[32] The RBA estimates that the major Australian

banks now consistently source around 25 per cent of their liabilities offshore.[33] This suggests that approximately $50

billion per year of funding is sourced from overseas.[34]

3.25

Although

offshore borrowing as a transaction is recorded on the capital account

(the counterpoint to the current account), is there a link between offshore borrowing and the

current account? For example, could a large inflow of funds exert upward

pressure on the value of a currency?

3.26

The Committee did not receive any direct evidence of a

possible relationship between large inflows of offshore funds and the current

account, but it would like to see Treasury undertake further research in this

area.

Committee views

3.27

The Committee agrees that the driver of the CAD in

recent years has been the household sector which has gone on a spending spree.

3.28

There is evidence that the household sector is now more

cautious than a couple of years ago.

Household consumption increased by 3 per cent in 2004-05, well below its

long-term average. In contrast, business

investment increased about 12 per cent and appears to be replacing

households as the main driver of economic growth.[35]

3.29

The Committee does not agree with Treasury's view that

there has been no obvious trend in the balance on current account. The evidence clearly suggests a long-term

trend towards larger deficits.

3.30

Could we be in the beginning of a new and higher

'step' level for a CAD averaging around 6 per cent of GDP, as implied in Figure

3.2?

3.31

The long-term trend in the CAD warrants close

monitoring by the Government. What would

it mean for Australia

if the CAD averages around 6% of GDP over an extended period? At what level does the CAD become

unsustainable? The Committee believes that such questions need to be asked,

researched and debated so that appropriate policy responses can be identified

and adopted as required.

3.32

An intriguing issue is that of a possible relationship

between the inflow of offshore borrowing and the current account. Can capital

inflow of such dimensions exert upward pressure on a currency, with all the

consequences of a higher-than-normal currency? Does it matter that much

of the overseas borrowings by the financial sector have been for unproductive

purposes, unlike corporate borrowings that would increase productivity and

exports? Are these borrowings keeping the currency at levels that make it

difficult for the export sector to compete in overseas markets? The Committee

would like to see more research to clarify whether such linkages exist and

their significance.

Recommendation 1

The Committee

recommends that Treasury undertakes more analysis related to the longer-term

outlook for the current account, and publishes its findings to enhance public

understanding and discussion.

Is the present level of Australia's

net foreign liabilities a problem?

3.33

Australia's

foreign liabilities have been increasing for many years, both in value and as a

proportion of GDP, but do they pose a major risk to the economy at this stage?

Table 3.2 shows details of Australia's

net foreign debt and net foreign equity positions since 1980.

Table 3.2: Australia's net foreign liabilities[36]

| |

Net foreign debt |

Net foreign equity |

Total net foreign

liabilities |

|

As at 30 June |

Net foreign debt $b |

% of total net foreign

investment % |

% of GDP % |

Net foreign equity $b |

% of total net foreign

investment % |

% of GDP % |

$billion |

|

1980 |

-7.9 |

29.0 |

6.1 |

-19.4 |

71.0 |

15.1 |

-27.4 |

|

1985 |

-53.1 |

67.2 |

23.5 |

-25.9 |

32.8 |

11.5 |

-78.9 |

|

1990 |

-130.8 |

75.7 |

34.0 |

-42.0 |

24.3 |

10.9 |

-172.8 |

|

1995 |

-190.8 |

74.7 |

40.6 |

-64.7 |

25.3 |

13.8 |

-255.5 |

|

2000 |

-272.6 |

82.9 |

43.7 |

-56.1 |

17.1 |

9.0 |

-328.8 |

|

2005 |

-430.0 |

83.2 |

49.8 |

-86.9 |

16.8 |

10.1 |

-516.8 |

Sources: ABS, Balance of Payments and International

Investment Position (Cat. No. 5302.0);

ABS, National Income, Expenditure

and Product (Cat. No. 5206.0)

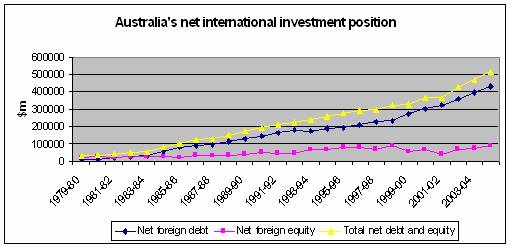

3.34

Most of the foreign investment coming into Australia

now is in the form of debt (borrowings) rather than equity investment, as shown

in Table 3.2 and graphically in Figure 3.3. As at June 1980, 29.0 per cent of

foreign investment came into Australia

in the form of borrowings and 71.0 per cent was in the form of equity

investment in Australian companies. By June 2005 the proportions had reversed

with 83.2 per cent coming in as borrowings and 16.8 per cent coming in as

equity investment.

Figure 3.3:

Australia's

net international investment, by debt and equity.

Source: ABS, Balance of

Payments and International Investment Position (Cat. No. 5302.0).

3.35

Table 3.3 shows the major sources of foreign debt

(borrowings) in the last four calendar years.

Note that this is total or gross foreign debt, whereas the

amounts in Table 3.2 are for net foreign debt.

Table 3.3: Major sources of foreign debt (borrowing) in Australia, calendar years

|

Country |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

| |

As at 30 December,

$ billion |

% of total |

|

UK |

123.8 |

150.8 |

155.3 |

179.1 |

24.3 |

26.2 |

25.4 |

25.6 |

|

USA |

114.4 |

136.7 |

159.0 |

165.1 |

22.5 |

23.7 |

26.0 |

23.6 |

|

International Capital Markets |

90.0 |

94.7 |

98.4 |

137.9 |

17.7 |

16.5 |

16.1 |

19.7 |

|

Unallocated |

25.6 |

26.9 |

33.1 |

50.3 |

5.0 |

4.7 |

5.4 |

7.2 |

|

Japan |

33.6 |

32.3 |

27.2 |

25.7 |

6.6 |

5.6 |

4.5 |

3.7 |

|

Belgium

/ Luxembourg |

9.0 |

7.3 |

10.9 |

17.7 |

1.8 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

2.5 |

|

Hong Kong |

26.1 |

29.6 |

21.0 |

16.8 |

5.1 |

5.1 |

3.4 |

2.4 |

|

Singapore |

22.8 |

20.8 |

17.6 |

15.0 |

4.5 |

3.6 |

2.9 |

2.1 |

|

Total all countries |

508.6 |

575.5 |

611.4 |

699.2 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Source:

ABS, International Investment Position, Australia: Supplementary Country Statistics 2004 (Cat No. 5352.0)

3.36

These figures raise the question whether lenders in Japan,

Hong Kong and Singapore

could be losing confidence in Australia

(perhaps because of the consistently high current account deficits we have

recorded in recent years?). Fortunately

the biggest lenders to Australia,

the UK and USA,

do not appear to share these concerns.

3.37

As at 30 June

2005, official (i.e. government) gross foreign debt liabilities

(borrowings) totalled $32.4 billion while official foreign debt assets and

reserve assets totalled $64.1 billion.

So the government sector is in surplus.[37]

3.38

As at 30 June

2005, of Australia's

total gross foreign liabilities $275.8 billion was repayable in Australian

dollars (38.9%) and $433.4 billion was repayable in foreign currencies (60.1%).[38]

Borrowings in US dollars represented 56 per cent of total foreign

currency borrowings as at 30 June 2005.[39]

3.39

The Round Table considered various aspects of Australia's

foreign liabilities. Mr Hawkins

pointed out that on several counts Australia's

foreign debt did not pose major problems:

There are three aspects that people consider in looking at

whether or not a debt is a problem. One aspect is the public-private ratio, and

the fact that ours is predominantly private is better than it being

predominantly public. The second aspect is the currency in which the debt is

denominated. In the classic cases of countries having debt crises, all of the

debts have been in foreign currencies. In Australia’s

case, quite a lot of our debt is in Australian dollars or is hedged one way or

another. The third aspect is the maturity structure of the debt. Ours is around

the OECD average. It is certainly not all short-term debt, as has been the case

in some countries that have had a crisis.[40]

3.40

However, Professor

Garnaut pointed out that having

predominantly private sector debt is not risk-free:

I am not seeking to draw a parallel between Australia and any of

the East Asian countries that went into crisis, but until right on the point of

the crisis, in the main, those economies had consenting-adult deficits, mainly

driven by debt-funded assets booms in the private sector. We are taking comfort

from the consenting-adults view of debt and the fact that it is in the private

sector. There have been lots of circumstances in other countries where that has

looked like a comfort for a while and then quite quickly has ceased to be a

comfort. Even in our own history, the most severe depression we ever had, in

the 1890s, followed the deflation of a private sector asset boom: the great

housing boom of the late eighties, which extended into 1890 and then collapsed,

which was greatest in Melbourne

but had Australia-wide ramifications in the early 1890s. It was not principally

a problem of government debt, and yet the consequences were severe.[41]

3.41

On the question whether equity is better than borrowings

Mr Pearson

commented:

There is no ‘right’ form of foreign capital inflow. Debt is not

‘bad’ and equity is not ‘good’. Remember, if you go back in the political

debate in Australia there was a time when people did not want to have equity,

because they thought that was ‘selling off the farm’, and the alternative was

to have debt. Neither is better or worse. They have different servicing

obligation characteristics and different ownership characteristics, which are

neither good nor bad. They are just different.[42]

3.42

Professor Garnaut

observed:

On the question of debt versus equity, if the concern that we

have about an unusually large current account deficit is that, in certain

circumstances, it would make us vulnerable to the need for painful adjustment,

selling off a lot of equity leaves us less vulnerable than selling off a lot of

debt, because if our economy comes upon harder times then the equity that

foreigners hold loses value; foreigners share in that adjustment.[43]

3.43

Mr Hawkins

indicated that the maturity structure of the debt is about average for the OECD

economies,[44] and Mr

Pearson provided the following detail:

On the question of foreign debt, the latest figures up to the

March [2005] quarter were that there is about $370 billion of gross foreign

debt in risk liabilities of more than one year’s maturity. The total

outstanding is about $690 billion. That is, more than half have more than one

year’s maturity.[45]

Servicing Australia's

foreign liabilities

3.44

The financing of a deficit on the current account

produces an increase in foreign liabilities.[46] Dr Gruen

commented that, while net foreign liabilities as a proportion of GDP cannot

increase indefinitely, he did not see the present circumstances as posing a

particular threat to Australia. He said:

As a consequence of that [current account deficits], net

external liabilities as a proportion of the size of the economy have been

gradually rising. But, again, that has been true for 20 years, and I do not

think there are any magic numbers here. At some point, net external liabilities

to GDP have to stop rising. They cannot go on going up forever, but it is far

from obvious how much further net external liabilities to GDP could rise. I do

not think it indicates emerging structural problems in the economy. In the broad,

I think it is a continuation of something that we have seen for an extended

period.[47]

3.45

Debt service ratios provide an indication of the

ability of a country to service its foreign liabilities. Table 3.4 shows how Australia's

debt service ratios have changed since 1990.

Table 3.4: Debt service ratios, 1990 - 2005

|

June

quarter |

Net

interest payments to exports, % |

Net

income[48] payments to exports, % |

Net

interest payments to GDP, % |

Net

income payments to GDP, % |

|

1990 |

19.6 |

25.0 |

3.1 |

4.0 |

|

1993 |

12.2 |

16.5 |

2.2 |

3.0 |

|

1996 |

11.5 |

19.7 |

2.3 |

3.9 |

|

1999 |

9.4 |

16.5 |

1.8 |

3.1 |

|

2002 |

8.9 |

12.8 |

1.9 |

2.8 |

|

2005 |

9.5 |

19.2 |

1.8 |

3.6 |

Source: RBA Bulletin, Australia's service

payments on net foreign liabilities,

Table H7.

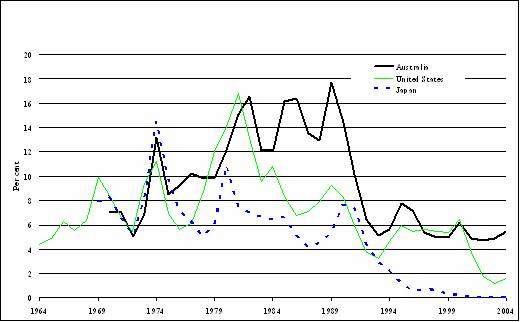

3.46

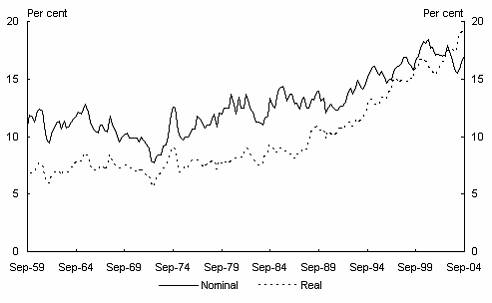

The figures in Table 3.4 show that net interest

payments as a percentage of export earnings almost halved between 1990 and

2002, but that ratio is now edging up.

The early 1990s was a period of very high interest rates, and Australia

obviously benefited from the significant fall in interest rates in subsequent

years (see Figure 3.4 below).

3.47

However, the ratio of net income payments as a

percentage of exports is again getting uncomfortably close to 20%. This ratio reflects both interest payments

and dividend payments and reinvested earnings. Foreign shareholders appear to

be reaping the benefits of their equity investments in Australian companies.

3.48

The high ratings given to Australia

by the international rating agencies suggest that they continue to regard Australia's

debt service ratios as manageable, despite the sharp increase in the net income

payments ratio in the last 3 years. On this point Professor Garnaut commented:

We have been able to finance the large current account deficit

because the international financial markets, the various sources of capital -

equity and debt—and other instruments of capital transfer have not formed a

view that the Australian deficit is unsustainable.[49]

3.49

Later in the discussion Dr

Gruen made a similar point:

The reason we were re-rated back up to AAA by the rating

agencies, even though the current account deficit remained large, was precisely

because their view about the rest of the economy was that it was more resilient

and that it was performing well based on a wide range of other factors.[50]

3.50

Mr Potter

made the observation that the international rating agencies are experienced

judges of risk:

What else, other than the international ratings agencies, can we

use to indicate independently that it [a high CAD] is a problem? Saying it is

at historical highs does not really indicate anything much.[51]

3.51

Mr Conroy

commented:

The AMWU believe that

foreign debt is not a problem as long as foreigners are happy to hold

Australian debt - which they have been in recent years because of Australia’s AAA credit rating and high interest rates

relative to the rest of the world[52].

3.52

But Mr Conroy went on to caution that the differential

between Australian and US interest rates would decrease as US rates go up. That will put pressure on the Reserve Bank to

lift Australian interest rates with potentially dire results for the local

economy.

3.53

As we have seen with movement of the net income

payments ratio, debt service ratios can change quickly if economic

circumstances change. Figure 3.4 shows

that international interest rates have been at historical lows, but some rates

are now showing signs of moving up. That trend is already starting to be

reflected in the higher interest payments ratios shown in Table 3.4. There is little to suggest the net interest

payments ratio will not worsen in the foreseeable future.

Figure 3.4: Short term interest rates, Australia, USA and Japan, 1964 –

2004

Source: RBA Bulletin datastream

3.54

The recent upturn in US and UK interest rates is

evident in Table 3.5, which shows the movement in interest rates in seven

countries since 2000.

Table 3.5: Short term interest rates, selected countries, 2000 - 2005

|

Country |

Calendar year annual

average % |

Month of June 2005, % |

| |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

|

USA |

6.5 |

3.7 |

1.8 |

1.2 |

1.6 |

3.2 |

|

UK |

6.1 |

5.0 |

4.0 |

3.7 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

|

Japan |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Germany |

4.4 |

4.3 |

3.3 |

2.3 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

|

EU av. |

4.8 |

4.4 |

3.5 |

2.6 |

2.6 |

2.6 |

|

Canada |

5.7 |

4.0 |

2.6 |

3.0 |

2.3 |

2.6 |

|

Australia |

6.2 |

4.9 |

4.8 |

4.9 |

5.5 |

5.7 |

Source: RBA Bulletin datastream

3.55

Low international interest rates have benefited

Australia. For example, while Australia's net foreign debt increased by $257

billion between June 2000 and June 2005, net interest payments to service the

debt only went from $14.6 billion in 2000-01 to $15.4 billion in 2000-05, as

shown in Table 3.6 below.

Committee views

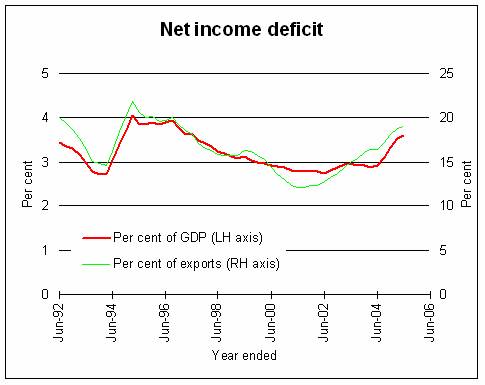

3.56

The May 2001 edition of Treasury's Economic Roundup

bulletin contained an article titled 'The

net income deficit over the past two decades'. The article found that the net income deficit

had shown steady improvement (i.e. decrease) since the mid-1990s, which augured

well for Australia's future ability to finance its foreign liabilities. However, that trend of steady improvement in

the net income deficit between 1996 and 2002 has not continued, with the trend

reversing and the net income deficit sharply worsening in the last year as

shown in Figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5: Net income deficit as a percentage of exports and of GDP

Sources: ABS, International Trade in Goods and Services (Cat.

No. 5368.0) - for export data; ABS, National Income, Expenditure and Product

(Cat. No. 5206.0) - for GDP data; Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin,

Table H7 - for net income payments

3.57

Table 3.6 shows Australia's net foreign liabilities

(debt and equity) and the amounts used to service those liabilities over the

last six years. The Committee notes with concern that the net income balance

has deteriorated sharply, from -$18.2 billion in 2000-01 to -$31.2 billion in

2004-05.

Table 3.6: Net foreign liabilities and their annual servicing amounts,

$billion

| |

Net foreign debt, as

at 30 June |

Net interest payments

over 12 months |

Net foreign equity, as

at 30 June |

Other net income

payments over 12 months |

Total net income

balance over 12 months |

|

1999-2000 |

-272.6 |

-13.4 |

-56.1 |

-4.8 |

-18.2 |

|

2000-01 |

-302.5 |

-14.6 |

-63.1 |

-4.1 |

-18.7 |

|

2001-02 |

-324.2 |

-13.6 |

-41.0 |

-5.7 |

-19.3 |

|

2002-03 |

-357.9 |

-11.6 |

-70.3 |

-9.9 |

-21.5 |

|

2003-04 |

-394.7 |

-12.5 |

-75.8 |

-11.2 |

-23.7 |

|

2004-05 |

-430.0 |

-15.4 |

-86.9 |

-15.8 |

-31.2 |

Source: Derived from RBA monthly bulletin, Tables H5 and H7.

3.58

This deterioration is also reflected in the debt

service ratios shown in Table 3.4 and shown graphically in Figure 3.5, above.

After several years of improving ratios, net income payments as a percentage of

exports jumped from 12.8 per cent to 19.2 per cent in three years. Over the same period net income payments as a

percentage of GDP rose from 2.8 per cent to 3.6 per cent

3.59

While these figures are still below the highs reached

in the December 1990 quarter (26.5 per cent and 4.3 per cent respectively), the

Committee considers that recent trends are worrisome.

3.60

The Committee is puzzled by the sharp increase in the

category 'other net income payments' (basically, dividends and reinvested

earnings paid to foreign equity holders). Most commentators suggest that this

is a result of the very high corporate profits earned in Australia in the last

couple of years, but can that be the whole story behind a four-fold increase in

just five years (from $4.1 b in 2000-01 to $15.8 b in 2004-05)? Such a dramatic change begs for a clearer

explanation by Treasury.

3.61

The Committee received conflicting evidence in relation

to the likely impact of movements in international interest rates on the income

balance. Professor Garnaut believes that if international interest rates go

back to historical average levels, that would have a significant impact on

Australia's income balance and possibly add a couple of points to the CAD.

However, the Treasury representatives (Dr Gruen and Mr Hawkins) argue that

hedging of foreign borrowings by Australian banks has greatly reduced the risks

posed by higher international interest rates.[53]

3.62

The Committee considers that it would be useful for

Treasury to undertake some modelling of various scenarios (such as a rise in

international interest rates, and a fall in the terms of trade), to ascertain

what impact such changes would have on the current account. The results of that research should be

published to facilitate understanding and debate on this important issue. The

Committee is concerned at recent trends, and believes that it would be useful

for Treasury to regularly publish detailed analyses of developments in the

trade balance and income balance.

Why are exports important?

3.63

Exports are important because, together with imports,

they make up the trade balance. If

exports grow faster than imports, the trade balance improves and there is a

likelihood that the current account deficit may decrease. However, if export growth is slower than

import growth, then the deficit in the trade balance widens which puts pressure

on the current account.

3.64

So, two key issues to consider are the prospects for a

better performance by exports in the future, and whether it is realistic to

hope for regular trade surpluses.

3.65

After matching import growth for most of the 1990s,

export growth slowed in 1997. It then

grew rapidly, to such an extent that in 2000-01 exports actually exceeded

imports. But since that time export

growth has again fallen behind import growth.[54]

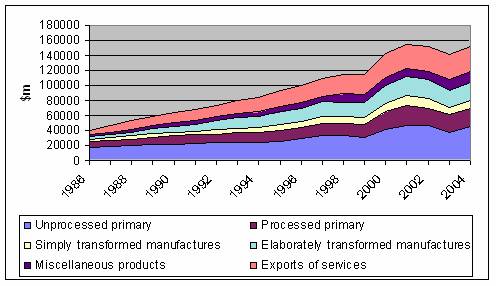

3.66

Figure 3.6 shows how exports have performed. After solid growth through the 1990s they

grew very quickly during 1999-2001.

However, they declined in 2002 and 2003 and are only now picking up

again due to higher prices of mineral and energy exports.

Figure 3.6: Exports of Goods and Services

Sources: Department of

Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), Exports

of Major Commodities Time Series; DFAT, Exports

of Primary and Manufactured Products Australia; ABS, Balance of Payments and International Investment Position (Cat. No.

5302.0)

3.67

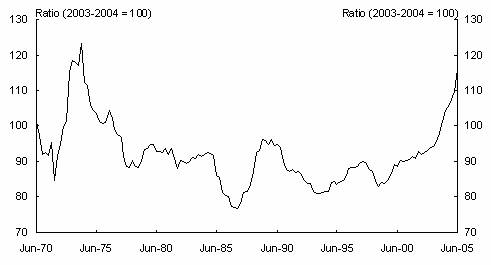

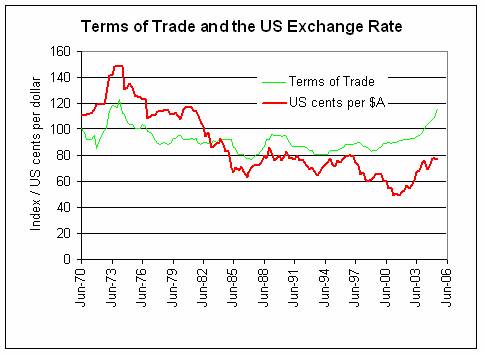

The commodity boom has pushed up the price of exports

relative to imports with the result that Australia's terms of trade are at 30

year highs as shown in Figure 3.7. The

terms of trade are expected to settle back to more normal levels in the next

few years.

Figure 3.7: Terms of trade, quarterly

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics cat. no.

5206.0.

3.68

A rise in the terms of trade adds to real national

income. According to Treasury's

submission: 'While real GDP expanded by 1½ per cent through 2004, the rise in

the terms of trade meant that real national income grew by almost 3 per cent'.[55]

3.69

If export

prices are so high, why have export revenues not accelerated? The

Treasury submission provides one explanation:

There is currently very strong demand for our resource exports.

This is reflected in high prices for these exports, but so far there has been

little rise in export volumes. This is partly due to firms underestimating the

strength of global demand and the lags associated with expanding capacity.

Furthermore, the diversity of ownership of the various linkages between mines

and ships has made coordination of improvements to transport and port

facilities difficult. Nevertheless, there is a substantial amount of investment

currently under way, which should allow significant expansion in these exports

in coming years.[56]

3.70

While Treasury is confident that export volumes for

resource exports will pick up shortly, it is less sanguine in relation to

exports of manufactures for the following reasons:

The volume of manufactures exports has been weak for some time.

This reflects maturing of the sector, the appreciation of the Australian

dollar, growing sophistication of Asian competitors and perhaps some diversion

of production as a result of high domestic demand.[57]

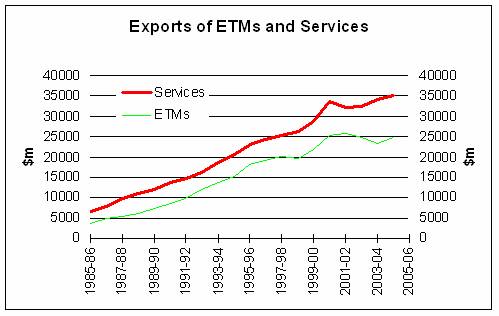

3.71

The export of Elaborately Transformed Manufactures

(ETMs) and Services both grew strongly from the mid-1980s to late 1990s,

increasing their share of total exports and increasing their contribution to

GDP. However, both have slowed

significantly in recent years, as shown in Figures 3.8 and 3.9.

Figure 3.8: Exports of Elaborately

Transformed Manufactures and Services

Sources: Department of

Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), Exports

of Major Commodities Time Series; DFAT, Exports

of Primary and Manufactured Products Australia; ABS, Balance of Payments and International Investment Position (Cat. No.

5302.0)

3.72

The declining contribution to the economy made by

exports of ETMs and services since about 1997 is apparent when they are shown

as a percentage of GDP, as in Figure 3.9.

Figure 3.9: Exports of ETMs and Services as a percentage of GDP

Sources: Department of

Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), Exports

of Major Commodities Time Series; DFAT, Exports

of Primary and Manufactured Products Australia; ABS, Balance of Payments and International Investment Position (Cat. No.

5302.0)

3.73

In Australia high terms of trade normally reflect high

commodity prices, and the exchange rate usually moves in sympathy with the

terms of trade. That means exports

become relatively more expensive and over time tend to fall, while imports

become relatively cheaper and tend to rise.

Receipts for exports of commodities reflect the higher export prices,

but manufactured products and services feel the impact of the higher exchange

rate and tend to fall.

3.74

Professor Garnaut pointed out that a number of periods

of economic prosperity ended when there was a sharp fall in the terms of trade

- as a result of which the exchange rate falls, inflationary pressures

increase, interest rates rise, investment falls, and government revenue (and

expenditure) falls. He said:

I am not predicting a

large and sudden retreat of the terms of trade, but one has to recognise that

it is historically normal to get these corrections, so it is one of things that

we should turn our minds to. If that were accompanied by a lift in global

interest rates, increasing the cost of servicing our external debt, it would

put an additional burden on our external accounts.[58]

3.75

Dr Simes noted that exports of ETMs and services grew

quickly from the mid 1980s to the late 1990s, due to a combination of factors

such as the low exchange rate; the removal of tariffs which made local firms

more internationally competitive; and the intensified engagement with

Asia. But the situation has changed:

If you look at the situation today, we have got a much more open

economy - that is, the imports to GDP is much higher than it was then [in the

1980s] ... it is hard to conceive of a scenario where we are going to get a lot

of mileage from the rural sector ... it is hard to see a situation where we get a

long-term big boost from the mining sector also. A lot of the big boost we have

at the moment is coming off the terms of trade ... the focus needs to come back

to ... do something a bit more proactive on manufacturing and services.[59]

3.76

Mr Hawkins pointed out that the greater diversity of

Australia's exports makes us less vulnerable.

While Professor Garnaut agreed with that assessment, he called for a

careful analysis of the reasons for the recent slowdown in exports of ETMs and

services. He said:

It is very important to the diminution of vulnerability in

future that we understand that slowdown [in exports]. My thoughts would go not

to new interventions by government to artificially increase incentives to those

sectors but to understanding the barriers of various kinds that have emerged to

continued rapid growth in services and manufacturing exports.[60]

3.77

Mr Potter agreed with Professor Garnaut – 'I understand

what you are saying: we should not be looking at industry specific measures to

artificially promote a sector, but we might want to look at industry-specific

barriers to those particular industries. I think that is absolutely correct [61]

3.78

Mr Conroy saw innovation as the key to increasing

exports of ETMs:

We believe that if we

increase innovation in the industry, and in manufacturing in particular, it

will increase our long-term competitiveness and our exports because we could

then compete with Asian countries not on the price of labour - which we can

never win - but on the price of our innovation and keeping ahead of the curve.[62]

Committee views

3.79

It seems to the Committee that there is little prospect

that Australia's net income balance will improve over the short-to-medium

term. If anything, the deficit on the

income balance is likely to worsen given the combination of rising net foreign

liabilities and rising US and UK interest rates. So if there is to be a significant

improvement in the CAD it will most likely have to come from the trade

balance. But how realistic is such an

expectation?

3.80

For the trade balance to have a significant impact on

the CAD, exports must consistently grow faster than imports. The ideal

situation would be for Australia to run a trade balance surplus on a regular

basis.

3.81

The Round Table noted that the short term prospects are

for strong growth exports, driven by high export prices for minerals and energy

and increased export volumes as infrastructure capabilities are expanded. But

if China's extraordinary growth falters, that scenario could quickly change.

3.82

Most of the discussion focused on the need to improve

the export performance of ETMs and services, which had stalled in recent years.

3.83

The Committee agrees that exports of ETMs and services

must perform well if there is to be a medium-to-long term improvement in the

trade balance. Unfortunately the Round

Table did not have sufficient time to consider possible strategies to achieve

that goal but in any case that is the role of the Australian Trade Commission

(Austrade).[63]

3.84

Austrade is the Government's export promotion agency.

Its focus is on the export of ETMs and services, as commodities are

internationally traded goods and exports of commodities basically look after

themselves.

3.85

Austrade's priority for the last 5 years has been to

double the number of exporters. To

achieve that goal Austrade has concentrated its efforts on small-to-medium

sized companies. Realistically, such

companies will make very little difference to Australia's overall exports for

many years to come. Large companies,

with the necessary financial and management resources, are the only ones which

can make a significant impact. Australia needs to nurture manufacturers and

service companies which export $10 million per annum, not $10 000.

3.86

The recent falling off of export growth suggests that

Austrade should urgently re-assess its priorities.

3.87

The Committee urges Austrade to develop strategies

which will increase the export of ETMs and services on a sustainable

basis. Exports as a whole, and in

particular ETMs and services, need to grow at a faster rate than imports for

the next few years if there is to be any chance for the CAD to achieve a

significantly lower average level.

Recommendation 2

The Committee

recommends the Government develop new strategies to promote the export of

Elaborately Transformed Manufactures and services to underpin a long term

improvement in the balance of trade.

What are the links between household debt, imports and the CAD?

3.88

The overall aim of this Inquiry was to explore possible

links between household debt, demand for imported goods and the current account

deficit (CAD). One of the specific terms of reference was to look at 'the

extent to which demand for imported goods by Australian households contributes

to the current account deficit'.

3.89

Mr Conroy saw a direct link between household

consumption and imports and the CAD. He

said:

The explosion in the

current account deficit in the last five years has been driven by an increase

in imports. It is not about borrowing more to fund capital expansion here; it

is about borrowing more and buying more consumer goods. If you look at the

growth rates in the last eight years, consumer goods have risen by about 140

per cent and capital good imports only by 70 per cent, so what is happening is

that Australians are buying more and more consumer goods from overseas. This is

part of an underlying structural problem here in that we are not funding

productive investment; we are borrowing now to purchase goods and we will pay

for it later ...[64]

Households and the CAD

3.90

There is a direct link between household debt and the

current account deficit. As discussed in

Chapter 2, from a savings/investment perspective, household debt has been the

principal contributor to the CAD in recent years.[65]

3.91

The official or government sector is now a net lender

(that is, the government sector is in overall budget surplus). The private

sector is made up of corporations and households. Corporations have

traditionally been heavy borrowers but in the last couple of years they have

become net lenders as high profits have exceeded investment. In contrast, households have traditionally

been net lenders but in recent years they have become net borrowers. Since

about 2000-01 household spending/debt has been the main driver of the current

account deficit.

Imports and the CAD

3.92

There is also a direct link between imports and the CAD

in the sense that imports are part of the trade balance which, in turn, is a

major component of the current account - see discussion on the trade balance in

paragraphs 2.10 to 2.20 in Chapter 2.

Households and imports

3.93

One could reasonably expect a link between households

and imports, particularly imports of consumption goods. Households consume both domestically produced

goods and services, and imported goods and services. These might be direct purchases of imported

televisions or cars or indirect purchases of, for example, kitchen appliances

if a house they buy is fitted with imported kitchen appliances.

3.94

Figure 3.10 shows the result of plotting the movement

of household liabilities against imports of consumption goods in the period

1987-88 to 2003-04, both measured at constant prices. Superficially, the graph suggests a strong

linear relationship between these two variables (reflected in the high

regression coefficient of 0.9711). However, it would be premature to read too

much into this graph without further research to more definitely establish the

causal links.

Figure 3.10: Statistical correlation between household liabilities and

imports of consumption goods

Sources: ABS, Financial

Accounts (Cat. No. 5232.0) - for total household liabilities; ABS, National Income Expenditure and Product

(Cat No. 5206.0) - for the implicit price deflator for non-farm GDP; ABS, International

Trade in Goods and Services (Cat. No. 5368.0) - for imports of consumption

goods.

3.95

Imports of consumption goods have grown strongly in recent

years, driven by strong consumer demand.

Strong Asian competition and an appreciating Australian dollar have

helped to keep prices of imported manufactured goods relatively low.

3.96

Figure 3.11 shows how imports of goods and

services have increased since 1981-82, and Figure 3.12 is a representation of

how the major components of total imports have changed. This shows that imports of consumption goods

have increased at a faster rate than the other components, thus increasing

their share of total imports of goods and services.

Figure 3.11: Imports of goods

and services, by major components

Source: ABS, International Trade in Goods and Services

(Cat. No. 5368.0)

3.97

Figure 3.12 shows the percentage of total

imports represented by its four components: consumption goods; capital goods;

intermediate goods; and services.

Consumption goods have increased their share of the value of total

imports of goods and services from 16 per cent in 1981-82 to 25 per cent in

2004-05, largely at the expense of intermediate goods and services.

Figure 3.12: Composition of

imports of goods and services, percentage of total

Source: ABS, International

Trade in Goods and Services (Cat. No. 5368.0)

3.98

A recent Treasury study examined the question: 'Why

have Australia's imports of goods increased so much?'[66]

The study noted that imported goods increased their share of nominal

domestic demand from about 11 per cent in the 1960s to about 17 per cent in

2004, as shown in Figure 3.13, below.

Figure 3.13:

Import penetration ratio (imports of goods as a % of GNE.

Chart 1: Import penetration ratio

(imports of goods as percentage of gross national expenditure)

Sources: Australian Bureau of

Statistics, Balance of Payments and

International Investment Position, cat.

5302.0 and National Income

Expenditure and Product, cat. 5206.0.

3.99

Treasury identified rising incomes and falling relative

prices for imports as the key factors behind increased imports. In the last 10 years growth in household

spending exceeded growth in income, with the short-fall made up from a

combination of decreasing savings and increasing debt.

3.100

The study concluded:

Over the past decade the volume of imported goods grew by an

average rate of 9 per cent a year, while real Gross National Expenditure grew

by 4½ per cent. While a large part of the fast growth in imports can be

explained by rising incomes and falling relative prices, other factors such as

changes in tastes and specialisation have also played an important role.[67]

Committee views

3.101

The Committee concludes that there are a number of

linkages between households and imports and the CAD, some more direct than

others.

3.102

The import penetration ratio (Figure 3.11) suggests

that imports represent a growing share of consumption. At least some of that would be at the expense

of local manufacturing. That is an

unfortunate fact of life in an increasingly globalised world. Communication and access are much easier

today. Australian consumers demand access to an ever-wider range of products in

quality and price, and that expectation can not be denied. The growth of

imports would be of less concern if exports as a percentage of GDP were also

growing, which is not the case, as shown in Figure 3.9.

What are the risks of a persistently high CAD?

3.103

In the December 2004 quarter the CAD set a new record

of 7.2% of GDP. A number of economists

pointed out that this record was reached during a period when Australia's terms

of trade were the highest in 30 years (which should have improved the trade

balance), and when international interest rates have been low (which should

have improved the income balance). One could reasonably have expected this to

be a period of relatively low current account deficits, instead of a period

when new records were being set.

3.104

The Treasury submission points out that the CAD has

fluctuated between 3 and 6 per cent over the last 20 years, commenting:

Fluctuations in the CAD are not a bad thing. They are a means by

which Australia smoothes consumption in the face of income shocks, such as the

Asian crisis. That is, the CAD, like the exchange rate, acts as a buffer or

shock absorber between domestic demand and global developments.[68]

3.105

The Round Table discussed the question of whether a

high level of CAD is necessarily bad, and the risks involved.

3.106

Dr Gruen saw the record deficit of 7.2% as a natural

part of the wide fluctuations which have characterised the CAD over the last 20

years. He said:

The Australian current account deficit has cycled between about

two and seven per cent of GDP for 20 years now and has averaged just under five

per cent of GDP for 20 years ... in the last several years we have seen both the

highest ratio to GDP and the lowest. My characterisation of the situation would

be that we have seen quite big cycles in the current account but no obvious

trend over that period. As I say, it has been around 5 percent - I think the

average is 4.75 per cent - of GDP for 20 years and there have been quite big

cycles around that.[69]

3.107

On the other hand, both Professor Garnaut and Dr Simes

expressed concern at recent levels of the CAD.

Professor Garnaut commented:

Having a current account deficit of seven per cent of GDP does

not prove that you have a big problem or crisis coming, but it should be a

warning bell that you should look very carefully at what is generating it and

at whether or not the things that are generating it are sustainable. It is an

unusual figure for Australia and very unusual in the world, especially amongst

developed countries ... in earlier periods when it has gone up to that level it

has been followed by quite severe adjustment problems. That does not prove that

it is a problem now but it should get us thinking. [70]

3.108

Dr Simes described his misgivings about a CAD of recent

proportions on several occasions during the Round Table, in the following

terms:

To me, a high current account deficit is a signal of something

not quite right and it is something that ... you should be cautious about.[71]

...

I think the size of the current account deficit is such that it

is symptomatic of an underlying problem and should be a source for doing

something about it. Again, because of the robustness of the financial markets

and the rest of it, I have tried to say that there is no need to do anything

quickly; it is more medium-term structural policies that we should be looking

at.[72]

...

Why is a larger current account deficit a problem? Unless it is

lifting the level of production - unless it is getting into investment and increasing

the base - there is an issue for longer-term economic welfare for the next

generation et cetera. To me it is symptomatic that we are not optimising our

long-term economic welfare.[73]

...

There is no right and

wrong level about the current account deficit in the first place. I am

concerned that we have been at 4½ per cent of GDP for 20 years, and it looks

like it is edging up. I would prefer it to be coming down ... the current account

deficit is too high today and looks like it is going to settle at an average

level which is uncomfortably high over the next, say, five years or whatever,

without policy adjusting it or doing something about it.[74]

3.109

Mr Conroy asserted that the high level of household

debt in Australia posed three specific threats to the economy:

The first is a

recession induced by household demand evaporating to service debts. The second

comes from the large external imbalance caused by the debt-induced current

account deficit and spiralling foreign debt levels. The final risk to the

economy originates from a misallocation of resources caused by the housing

bubble and the consumer debt explosion reducing the long-term competitiveness of

the Australian economy.[75]

3.110

Mr Conroy felt that the Australian economy is

vulnerable not only to recession caused by a collapsing consumer demand but

also to a change in the international sentiment regarding the Australian

economy.[76] Professor Garnaut sounded a similar

cautionary note: 'the views of international markets can change

rather quickly.' [77]

3.111

The Round Table discussed

various risks facing the private sector. Dr Gruen advised that in the

aftermath of the Asian crisis Treasury has kept a close eye on the liabilities

of the private sector. He said:

There has been much more careful analysis by regulatory

authorities of the sorts of liabilities in the private sector that could

ultimately cause systemic problems. The lesson from the Asian crisis is that

those are exactly the sorts of things you have to look at carefully. That is

precisely what we have done ... if one is going to have a consenting-adults view

about the current account it is extremely important to take a view about

possible shocks that could lead to systemic problems. In the Asian crisis case

economists were not very good at predicting it. With the benefit of hindsight,

we are much better at predicting things.[78]

3.112

The Round Table considered whether a sharp fall in

house prices would impact on the ability of households to make their loan

repayments. On this point, Dr Simes

said:

My view is that it is not only the fact that you have a large

proportion of the population who are not in debt and who can support the

others; it is also that the financial sector is attuned to providing credit et

cetera in a fairly smooth way. Given that most of this debt is secured against

a house and is being serviced by regular income, the real problem is only going

to arise if you have a sharp lift in unemployment, not just if house prices

fall.[79]

3.113

Both Dr Gruen and Mr Potter referred to a recent APRA[80] survey which found that the major

banks could comfortably accommodate a 30 per cent slump in housing prices.

3.114

Dr Simes thought there is a low risk that interest

rates would go to levels which would result in severe unemployment and have a

major impact on the ability of households to service their debts. On the other hand, if foreign investment is

withdrawn Dr Simes said that the exchange rate would respond appropriately to

restore balance:

If foreign investment is withdrawn, the adjustment will be

through the exchange rate - that is, foreign money will be available at a price

and it will be the exchange rate that does the buffering, as we saw in the

Asian financial crisis, if you like. That will be manageable unless you have a

system in the price-wage interactions where it is going to get into ongoing

inflation, and that is hard to see in the current structure of the economy or

for the next five years. You could not rule that coming back into play at some

point, but it is a long way off.[81]

3.115

The Round Table discussed the adverse

impact on local manufacturers of large fluctuations in the exchange rate within

relatively short periods, as happened about 5 years ago, when the exchange rate

went down to US$0.49 and then moved up to US$0.80. That kind of wide

fluctuation puts considerable stress on local manufacturers as they endeavour

to adjust to rapidly changing circumstances.

3.116

Dr Gruen agreed that this had put pressure on domestic

manufacturers but said that a floating exchange rate is essential to sound

economic management:

The recent period ... moving from US49c to something close to

US80c, is not very usual. We have been in an extremely unusual circumstance of

going from being viewed as the old economy in 2001 to this huge rise in the

terms of trade, and the currency has gone with it. Given that the terms of

trade are something that we get dealt largely by the rest of the world,

allowing the currency to move with them may have sectoral implications that

some people [manufacturers] would not like but, in terms of the stability of

the overall economy, it is a huge advance on the last time we had a huge

terms-of-trade rise like this, which was in 1973-74. The Australian economy did

not cope well with that. We ended up with a big rise in inflation and a lot of

other things as well. Nothing has only good sides, but my judgement is that

this is a much better way of allowing

the economy to adjust than the alternatives.[82]

3.117

Dr Gruen reinforced the importance of a floating

exchange rate by describing the important but adverse role fixed exchange rates

played in the Asian financial crisis. He

said:

... it came as a rude shock to everyone when the Asian countries

went into severe recessions. We discovered that they were running either fixed

exchange rates against the US or effectively fixed exchange rates against the

US. It was perhaps not realised that the financial health of most of the

economies, not only the financial system but also the non-financial system, was

inextricably tied to this exchange rate policy. In other words, once the

currency depreciated significantly, the unhedged foreign borrowings in the

companies and the financial system bankrupted large parts of the economy.[83]

3.118

Mr Conroy believes that manufacturing sector has

suffered because interest rates have been kept artificially high so as to

attract the funds required to meet excessive household consumption. This has pushed up the exchange rate, which

has made imports relatively cheaper and hurt local manufacturers and

exporters. He said:

The reliance on capital

inflow to fund consumer debt has adversely affected the manufacturing sector ...

it has crowded out direct foreign investment in manufacturing by forcing

interest rates and exchange rates to be higher than would otherwise have been

the case ... it has allowed unsustainable growth in domestic demand resources

which would otherwise have been allocated for manufacturing expansion ... [and] Governments continue to believe that high

and sustained economic growth can be achieved by letting the finance sector

drive the economy ... [they] no longer believe in the importance of

manufacturing.[84]

What could improve the CAD?

3.119

The Round Table discussed various ways in which the CAD

could be brought back to lower levels.

3.120

Professor Garnaut believes the CAD will eventually

self-correct, but questioned the economic and social cost of leaving such

adjustment solely to market forces. He

commented:

There is a sense in which there cannot be a long-term current

account deficit problem because in its nature it is self-correcting. Indonesia

and Thailand had current account deficits in 1996 that some people thought were

worrying. They had large current account surpluses by late 1998 and 1999, so

there is a sense in which there was no current account deficit problem because

it was self-correcting. The problem was the consequences of the adjustment that

the economy had to go through.

So the issue we are talking about is not really a problem of

whether the current account deficit will adjust or whether in the end whatever

deficit is there will be financed - by definition it will be. The question is: what will the process of adjustment be and

what stress will that place on government budgets, on unemployment and on

economic activity - or, to put it another way, will it give us a recession like

similar adjustments have in the past?

So the questions in the end become ones of vulnerability to

circumstances changing and forcing adjustment and of our capacity to handle

without excessive pain the adjustments that will be necessary.[85]

3.121

There was general agreement that the cooling-off of the

housing boom would diminish the 'wealth effect' on households which, coupled

with rising interest rates (and, more recently, rising fuel prices) would in

turn reduce household spending and borrowing.

Dr Gruen expressed it as follows:

Their [Reserve Bank] latest estimate ... is that in the 18 months

to the December quarter 2003 house prices in Australia went up 29 per cent.

Over the last 18 months they went up by exactly nothing ...the consequences of

that for the savings and investment balance of the household are going to be

very substantial. So I think there are self-correcting forces in play in the

Australian economy which should move us in the direction of smaller current

account deficits.[86]

3.122

Professor Garnaut supported this assessment:

You cannot have your households dis-saving forever, with that

being balanced by ever-increasing asset values - in this case, bubble housing

values. We are going through an adjustment now, as the housing boom has reached

a plateau ... Over time, one would expect that to significantly bring down

consumption and raise saving rates.[87]

3.123

Although Dr Simes considered the high level of the CAD

to be of concern, he does not see a crisis situation yet. He said that there

are several reasons why the level of the CAD may come back to a lower level—for

example, through a slowdown in economic demand and activity induced by a fall

in the terms of trade; or a reduction in house prices; or if foreigners

withdraw capital leading to a fall in the exchange rate. He expressed the belief that the financial

sector is strong enough to absorb such adjustments. He concluded:

The current account is an issue and something we should be

acting to address, but we can do it over the medium term, and we should be

looking at medium-term policy changes either related to savings or to exports.[88]

3.124

An increase in national savings would enable more of

Australia's investment to be financed from domestic savings rather than by

borrowing overseas, thus improving the income balance of the current account.

Additionally, if exports grow faster than imports, the trade balance is

improved. Enhancing domestic savings and

lifting export growth helps the current account.

3.125

Dr Simes suggested looking at 'superannuation and the

like',[89] and recommended raising the superannuation contribution rate from 9 to 15

percent.[90]

3.126

Mr Pearson commented on the impediments that limit the

amount of superannuation people are prepared to take out. He felt that, before

increasing the contribution rate, more should be done to remove the impediments

to superannuation such as the taxes and the residual benefit limits.[91]

3.127

Mr Potter disagreed and argued that targeting

superannuation would not be an appropriate policy response to address the level

of CAD. He said:

We think that super policy should be driven on its own merits,

not because of the effect it has on national savings. I will separate it into

two issues. You can either have the government investing in people’s super -

that is one possibility - or increase people’s compulsory contributions. On the

first one, if the government puts more money into people’s super then that

actually reduces the fiscal balance, so you may end up with no benefit to

national savings. You might have an increase in the amount in people’s super

accounts, but a reduction in the government deficit and you would only be a

little bit better off. On the other hand, you could, for example, increase the

compulsory component of superannuation. We do not think that is such a good

idea because, in a sense, super is like a payroll tax. I think the last thing

that businesses want is to have is an increase in payroll taxes.[92]

Are the self-correcting mechanisms

working?

3.128

A recent article in The

Economist pointed out that a number of self-correcting mechanisms appeared

to have 'jammed' and were no longer working as they were supposed to according

to conventional economic theory. The article gave three examples, based on the

USA whose CAD is forecast to exceed 6 percent of GDP in 2005 (i.e. a deficit of

over US$800 billion).

Firstly, in theory a rapidly rising CAD should cause investors

to demand higher interest rates to compensate them for the increased risk of

currency depreciation. Dearer money then

helps to dampen domestic spending and thus trim the external deficit. This is

what happened when America's CAD exploded in the first half of the 1980s. Real bond yields rose, cooling domestic

demand. Along with the cheaper dollar, this helped to reduce the deficit. This

time, however, the adjustment mechanism has jammed: real American bond yields

have fallen not risen over the past few years, partly because Asian central

banks have been eager to buy US Treasury bonds to prevent their currencies from

rising. So long as low bond yields continue to support America's housing bubble

and hence strong consumer spending, they will block any significant reduction

in the CAD.

Secondly, in the past a rapid rise in consumer borrowing and

spending would cause a central bank to push up interest rates to curb

inflation. Today, however, inflation is held down by cheap goods from China and

other low-wage economies, and inflationary expectations are well anchored

thanks to the credibility of central banks.

As a result, central banks have been able to hold interest rates below

the growth in nominal GDP (the income from which debts must be serviced) for a

prolonged period. This has, in effect,

lifted any constraint on credit growth, allowing a bigger build-up of private

sector debt.

Thirdly, a broken circuit is apparent between interest rates and

growth. Sluggish economies with low

inflation require lower real interest rates than economic sprinters. Yet

despite its faster growth, America's real bond yields are lower than Japan's

and about the same as in the euro area. Yields are arguably too low for America

but too high for Germany and Japan, causing the growth gap to persist. [93]

3.129

The article describes interest rates and bond yields as

the traffic lights of the global economy: they tell economies when to go and

when to stop. The market would punish

economies where governments or households borrow recklessly with higher bond

yields, prompting them to tighten their belts. Prudent economies would be

rewarded with lower real rates. But

today financial markets are doing a poor job as economic watchdogs: in

particular, America's profligacy is being subsidised rather than punished.

3.130

In a closed economy, according to the article, if a

government increases its budget deficit it must pay higher interest rates to

persuade domestic investors to hold more bonds.

But if it can tap global savings, it can borrow more cheaply because a

smaller rise in rates is needed to attract the required funds. Even so, an

efficient international capital market is supposed to ensure that capital is

allocated to the most productive use.

Yet much of the recent inflow of foreign money into America is not

financing productive investment, but a housing bubble and a consumer binge.

3.131

A possible explanation is that, with interest rates low

everywhere, investors are hungry for any sort of yield. This has made them more willing to buy

high-yield bonds, and has pushed down the spread that riskier borrowers must

pay compared with safer borrowers. When

financial conditions tighten, investors are sure to become more discriminating

again.

3.132

The article concludes by warning that when the

inevitable correction comes, it will be all the more painful because of the

large imbalances which have developed.

3.133

The Committee acknowledges that the focus of the

article in The Economist was the USA,

but notes the many apparent similarities with the situation in Australia, with

its big increase in household consumption and debt and the related housing boom

of 2002-04.

3.134

A study by the US Federal Reserve Board in 2000 of a

number of countries found that self-correcting mechanisms should kick in when a

CAD reaches about 5 per cent of GDP:

A typical adjustment occurs after the current account deficit

has grown for about four years and reaches about 5 percent of GDP. The results

from previous episodes suggest that reversals involve a real depreciation of 10

to 20 per cent and slow real income growth for a period of about three years.

Real export growth, declining investment, and an eventual levelling off in the

net international investment position and in the budget deficit-GDP ratio are

also likely to be part of the adjustment.[94]

3.135

A speech in May 2004 by Edward Gramlich, Governor of

the US Federal Reserve Board, focused on the sustainability of rising trade and

budget deficits.[95] These issues are now attracting much more

detailed analysis and debate in the USA, as they should be in Australia.

3.136

Australia has now had a CAD of over 5 per cent of GDP

for 11 consecutive quarters, and the expected correction in the exchange rate

has not taken place. Could this be a practical example of the 'jamming'

referred to by The Economist (above)?

3.137

In another warning that global imbalances need

watching, the International Monetary Fund's World Economic Outlook bulletin

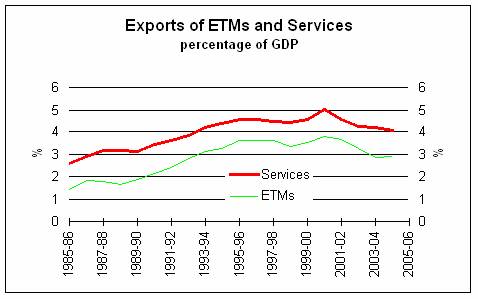

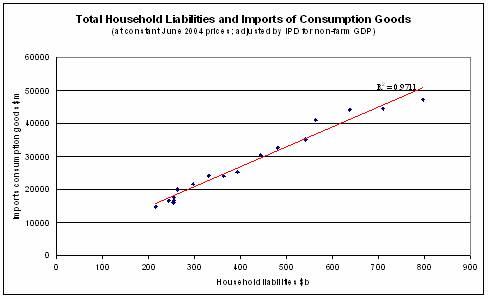

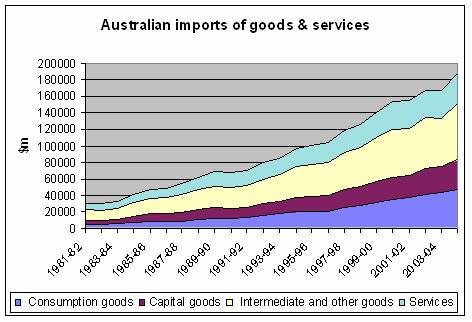

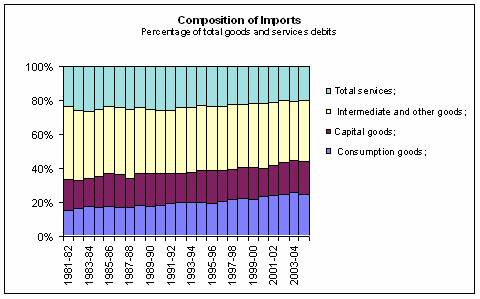

released in September 2005 warns that the USA's growing trade and budget