Chapter 2 - Background to Australia's

current account

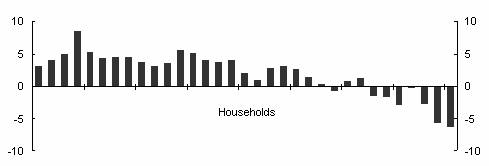

The household sector has

been borrowing (indirectly, via the banking system) from the rest of the world

to fund spending in excess of income.[2]

What is the current account?

2.1

Put simply,

the current account indicates whether a country has absorbed more goods and

services and income than has it produced.[3] A current account deficit means that

total payments exceed total receipts, while a current account surplus means the

reverse.

2.2

Another way of looking at the current account is

through savings and investment. If a country's balance on current account is in

deficit, then national investment exceeds national saving and the country is a

net recipient of investment funds from the rest of the world.

2.3

A current account deficit (CAD) is financed by

borrowing from overseas and/or by foreign equity investments in Australia.

Australia's

current account[4]

2.4

Since 1950, Australia

has had a surplus on its current account in only four years: 1950-1, 1952-3,

1956-7, and 1972-3. The other years all

recorded current account deficits. [5]

2.5

The annual balance on current account from 1959-60 to

2004-05 is shown in Table 2.1. In

2004-05 the balance on the current account was in deficit by $57.2 billion.

Table 2.1: Balance on current account, original, $billion[6]

|

Year

|

Balance on current

account, $b

|

Year

|

Balance on current

account, $b

|

|

1959-60

|

-0.5

|

1984-85

|

-11.3

|

|

1964-65

|

-0.8

|

1989-90

|

-22.7

|

|

1969-70

|

-0.8

|

1994-95

|

-28.4

|

|

1974-75

|

-1.3

|

1999-2000

|

-32.6

|

|

1979-80

|

-2.2

|

2004-05

|

-57.2

|

Source: ABS, Balance of Payments

and International Investment Position (Cat. 5302.0)

2.6

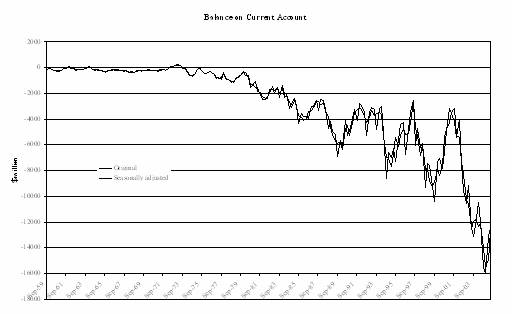

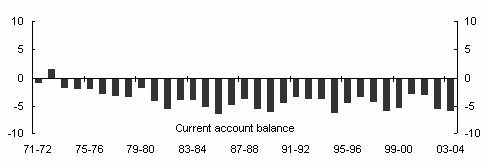

Figure 2.1 shows the movement in the balance on current

account on a quarterly basis since the September 1959 quarter, in value

terms. Both original and seasonally

adjusted figures are shown. Table 2.1

shows the annual results, while Figure 2.1 graphs the quarterly movements.

Figure 2.1: Australia's balance on current account, quarterly (September 1959 quarter to

June 2005 quarter), $m, original and seasonally adjusted

Source: ABS, Balance of Payments

and International Investment Position (Cat. 5302.0)

2.7

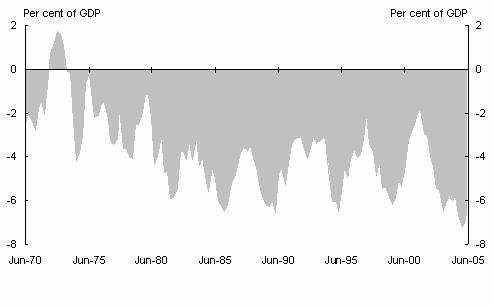

The current account is often expressed as a percentage

of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to put its economic significance into context.

The CAD fluctuated between 2 and 3 per cent of GDP in the 1960s and 1970s and

between 4 and 6 per cent of GDP in the 1980s and 1990s. It has been over 5 per cent for the last 11

quarters (i.e. since the June 2003 quarter).

2.8

Australia's

balance on current account as a percentage of GDP since 1970 is shown in Figure

2.2. Over that period Australia

has recorded a deficit in every year except 1972-3.

Figure 2.2: Current account balance as a percentage of

GDP, quarterly

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)

catalogue no. 5302.0 and 5206.0.

2.9

Treasury's submission to the Inquiry explains that

there are two ways of looking at the current account - from a trade perspective

and from a savings/investment perspective.[7]

The current account from a trade

perspective

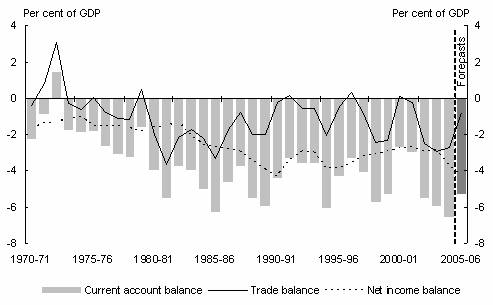

2.10

From a trade perspective, a country's current account

is the sum of its trade balance (exports of goods and services less imports of

goods and services) and its income balance (interest payments and dividends

received less paid) and current transfers. [8]

2.11

Figure 2.3 shows that the deficit in the income balance

(the broken line in the graph) has usually been bigger than the deficit in the

trade balance (continuous line) thus contributing more towards the overall

deficit in the current account. However, most of the fluctuation in the current

account has been as a result of fluctuations in the trade balance, as the net

income deficit has been relatively stable, or slowly declining, since its sharp

run up in the mid-1980s.[9]

Figure 2.3: Current account balance as a per cent of GDP,

year average

Source:

Australian Bureau of Statistics cat. no. 5302.0 and 5206.0, and

Treasury.

Australia's

trade balance

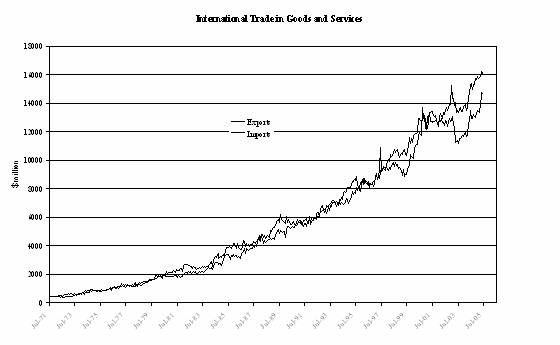

2.12

Australia

has generally run a deficit in its balance of trade - that is, it tends to

import more goods and services than it exports. Figure 2.4 shows that the gap

between imports and exports has usually been relatively small. However, the value of exports of goods and

services has exceeded the value of imports of goods and services in only 6

years since 1970.

Figure 2.4:

Australian imports and exports of goods and services, 1971 - 2005

Source: ABS, International Trade in Goods and

Services (Cat. No. 5368.0). Monthly

figures are seasonally adjusted.

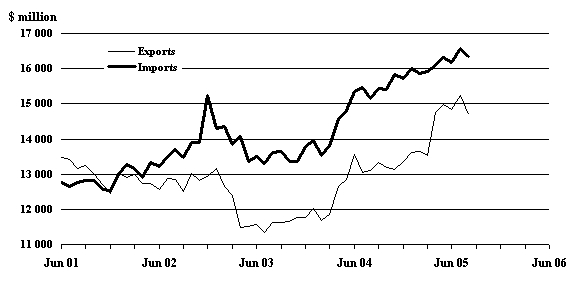

2.13

Small balance of trade surpluses were achieved in 1996-97

and again in 2000-01, but then significant trade deficits were recorded in

2002-03, 2003-04 and 2004-05. Figure 2.5 shows these changes on an enlarged

scale for the period June 2001 to June 2005. The trade deficit narrowed

slightly in the June 2005 quarter as higher export prices for minerals and

energy took effect and exports grew faster than imports, but then widened again

in August 2005, when exports slowed more than imports.

Figure 2.5: Australian imports and exports of goods and services, 2001

- 2005

Source: ABS, International Trade in Goods and Services (5368.0)

2.14

Predictions are that export volumes of minerals and

energy commodities are beginning to pick up, as infrastructure constraints are

eased. The combination of high export

prices and higher export volumes should result in the gap between exports and

imports closing over the next few months.

2.15

The Treasury submission notes that the trade balance

tends to move with the economic cycle. When domestic demand grows faster in Australia

than in the rest of the world, import volumes tend to rise more than export

volumes and so the trade deficit becomes larger (as has happened recently).

During the recession of the early 1990s (and the slowdown around 2000), import

volumes were more subdued and the trade deficit was correspondingly smaller.[10]

Australia's

income balance

2.16

The income balance shows the annual cost of servicing Australia's

net foreign liabilities. The change over the last 20 years in Australia's

net foreign liabilities is shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Australia's net foreign liabilities[11], current prices, $billion

|

As at 30 June

|

Net foreign debt (borrowing), $b

|

Net equity liabilities, $b

|

Total net foreign liabilities, $b

|

|

1985

|

-53.1

|

-25.9

|

-78.9

|

|

1990

|

-130.8

|

-42.0

|

-172.8

|

|

1995

|

-190.8

|

-64.7

|

-255.5

|

|

2000

|

-272.6

|

-56.1

|

-328.8

|

|

2005

|

-430.0

|

-86.9

|

-516.8

|

Source: RBA monthly bulletin,

Table H5 Australia's net

foreign liabilities

2.17

Since 1950 Australia

has always had deficits in its income balance - that is, Australia

has paid more in interest payments and dividends on foreign borrowings and

foreign investment in Australia

than it has received from money Australia

has lent and invested overseas.

2.18

The main components of the income balance are payment

of interest on foreign debt (borrowings) and payments of dividends and

reinvested earnings on equity investments.

These are shown in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Major components of Australia's income balance at current prices, 1999-00 to 2004-05, $billion[12]

|

Year

|

Net interest payments

|

% of total

|

Other net income payments[13]

|

% of total

|

Total net income payments

|

Total %

|

|

1999-00

|

-13.4

|

74%

|

-4.8

|

26%

|

-18.3

|

100%

|

|

2000-01

|

-14.6

|

78%

|

-4.1

|

22%

|

-18.7

|

100%

|

|

2001-02

|

-13.6

|

70%

|

-5.7

|

30%

|

-19.3

|

100%

|

|

2001-03

|

-11.6

|

54%

|

-9.9

|

46%

|

-21.5

|

100%

|

|

2003-04

|

-12.5

|

53%

|

-11.2

|

47%

|

-23.7

|

100%

|

|

2004-05

|

-15.4

|

49%

|

-15.8

|

51%

|

-31.2

|

100%

|

Source: RBA Monthly Bulletin,

Table H7 Australia's service

payments on net foreign liabilities

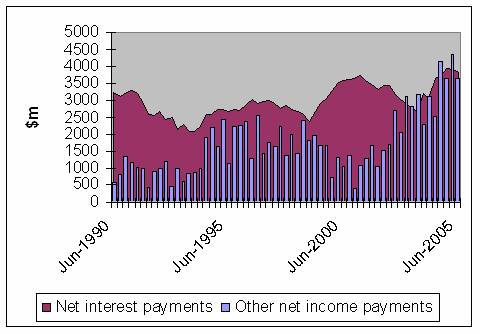

2.19

Figure 2.6 shows how the major components of the income

balance 'net interest payments' and 'other net income payments' have changed

since 1990, on a quarterly basis.

Figure 2.6: 'Net interest payments' and 'Other net income payments',

quarterly changes, $m

Source: RBA Monthly Bulletin,

Table H7

2.20

Until recently the 'Other net income payments'

component of the income balance (shown as bars in Figure 2.6) was less

significant than the 'Net interest payment' component within the total income

balance. However, as Figure 2.6 shows

that is changing with both components now representing about 50% each of the

total. Changes in the income balance are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3

(paras 3.49 to 3.68).

The current account from a

savings/investment perspective

2.21

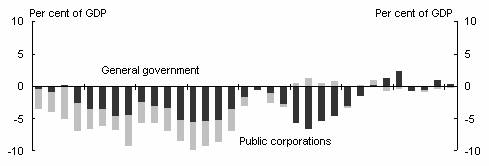

The Treasury submission explains that while the CAD is

most commonly discussed from a trade perspective, it is best understood within

a saving/investment framework. [14] This is illustrated in Figure 2.7.

2.22

The first three panels of Figure 2.7 show ‘net

lending’ (when saving exceeds investment) or ‘net borrowing’ (when saving falls

short of investment) by government, corporations and households in Australia.

The final panel is the current account balance (which can be thought of as ‘net

borrowing’ by Australia

from the rest of the world). The numbers in first three panels add up to the

current account balance shown in the final panel.

Figure 2.7: Net lending, year average

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics cat. no.

5204.0, 5302.0 and Treasury (original data).

2.23

Figure 2.7 shows that for most of the period since 1970

the public (or official or government) sector (panel 1) was a net borrower, but

it has now become a small net lender - that is, the public sector is in overall

budget surplus.

2.24

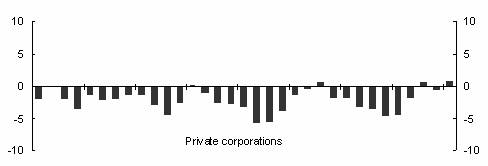

The private sector is made up of private corporations

and households. Panel 2 in Figure 2.7 shows that while private corporations

have traditionally been borrowers, in recent years they have become net lenders

as high profits exceed investment. In

contrast, households (panel 3) have traditionally been net lenders (due to

strong savings) but in recent years they have become net borrowers. Households have been borrowing (indirectly,

via the banking system) from the rest of the world to fund spending in excess

of income.[15]

2.25

Over the past 15 years the household sector has changed

progressively from being a net lender to the rest of the economy to being a net

borrower. This reflects both an increase in household investment and a fall in

household saving (see Chapters 4 and 5 for a detailed discussion of household

debt in Australia).

2.26

The graphs in Figure 2.7 show that, from a

savings/investment perspective, since about 2000-01 Australian household

spending/debt has been the principal contributor to the current account

deficit.

How does the CAD impact on net foreign liabilities?

2.27

Australia

has nearly always had a deficit on its current account, although it wasn't

until the 1980s that these deficits were associated with a build up of foreign

debt (borrowings). Earlier deficits were relatively small and the capital

inflow to finance those deficits was largely in the form of long-term equity

investment. However, from the early 1980s the size of the average CAD almost

doubled, to 4.4 per cent of GDP, over the next 20 years.[16] Almost all the capital inflow which

financed these higher deficits was in the form of overseas borrowings rather

than equity.

2.28

While current account deficits contribute to a nation's

net foreign liabilities, the CAD for a given period does not necessarily equal

the change in net foreign liabilities that occurred over that period. For

example, in 2004-05 the current account deficit totalled $57 billion, but net

foreign debt (borrowings) increased by $35 billion and net foreign equity

increased by $11 billion, giving a total increase in net foreign liabilities of

$46 billion over that 12 months.

2.29

The relationship between the CAD and net foreign

liabilities is quite complex. A detailed

explanation is provided in Appendix 3.

How does Australia's

current account compare with other countries?

2.30

In 2004, of the 30 countries included in the bulletins

of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), thirteen

had current account surpluses and seventeen had deficits. The overall average for the OECD was a

deficit of 1.2% of GDP.[17]

2.31

Of the countries with surpluses, only Austria

(0.3%) had a current account surplus of less than 2.6%. The highest surpluses were recorded by Sweden

(8.0%), Luxembourg

(8.8%), Switzerland

(12.0%) and Norway

(13.8%).

2.32

Of the countries with a current account deficit, the

lowest was France

(0.3%) and the highest were Australia

and New Zealand

(both 6.3%), Portugal

(7.8%), Iceland

(8.1%), and Hungary

(9.4%).

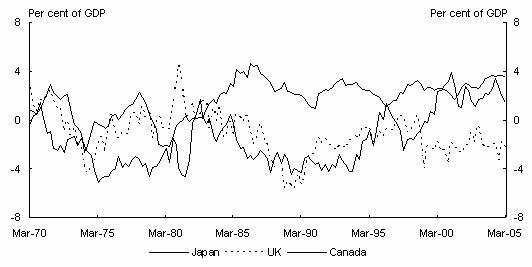

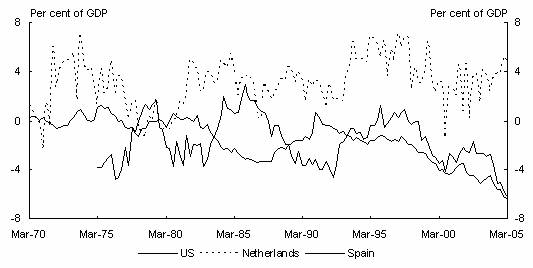

2.33

Figure 2.8 (below) shows the movement in the current

account as a percentage of GDP of six OECD countries since 1970: Japan,

UK and Canada

are shown in the first panel, and the USA,

the Netherlands

and Spain in

the second panel.

Figure 2.8: Current account balance as a per cent of GDP,

quarterly, selected countries

Source: OECD

Economic Outlook Bulletin

2.34

The graphs suggest that the early 1980s were a turning

point for several countries. Since then, the USA,

UK and Spain

have experienced mainly deficits in their current accounts while Japan

commenced a period of sustained surpluses. That was also the time that Australia's

average CAD stepped up to a new level (see Figure 3.2).

2.35

Canada

has had an interesting experience with its current account. After recording a number of relatively high

current account deficits in the 1970s and 1980s, in 1994 the size of the

deficits started shrinking and Canada

has recorded current account surpluses since 1999.

2.36

Given the similarities between Australia

and Canada, the

Committee feels that there may be salient lessons to be learnt from Canada's

experience.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page