Chapter 6

Transitional assistance

6.1 The CPRS package involves transitional assistance to companies heavily

affected by the CPRS. There are two primary reasons. The first is to avoid

'carbon leakage'. The second is to assist firms to transit to operation in a

carbon-constrained environment whilst maintaining energy security.

6.2 Firms engaged in emissions-intensive-trade-exposed activities may be

constrained in their ability to pass through the increases in the carbon cost

because they are price takers on the world market. Introducing carbon

constraint ahead of other countries could lead to a loss of competitiveness for

these industries and lead to 'carbon leakage'.[1]

Carbon leakage

6.3 Carbon leakage is most commonly expressed as a fear that having strict

rules in Australia will lead to emissions-intensive industries shifting to

countries without emissions caps and with the result of increased emissions or

no global reduction in emissions occurring.

6.4 There are a number of conditions that must be in place before carbon

leakage in this narrow sense would be likely to occur:

-

the emissions permit price in Australia is a significant proportion of costs;

-

there is no similar price currently being imposed in an alternative production

centre;

-

there is unlikely to be a similar price imposed in an alternative

production centre for a significant proportion of the life of the project;

-

there are not large relocation costs;

-

there

are not significant damages to the company's reputation from being seen to

avoid responsibility for its greenhouse gas emissions[2];

-

shifting production does not lead to offsetting increases in other ongoing

costs (eg the transport of raw material from Australia, or higher prices for

raw materials in the other centre); and

-

the production process in the alternative centre

is more emissions-intensive.

6.5 Another variant of 'carbon leakage' is where the Australian producer

does not move offshore, but loses market share to an overseas competitor as a

result of Australia introducing a price for greenhouse gas emissions. The

relocation costs argument above does then not apply, but importantly the final

point still does.

6.6 A number of witnesses asserted that there remains a risk of 'carbon

leakage', notwithstanding assistance for emissions-intensive, trade-exposed

industries (EITEs):

A decay in the assistance rate over time will make cement

produced in Australia uncompetitive compared to imported cement. If this leads

to lower output from, or even the closure of Australian cement plants, offshore

plants would increase production – hence carbon leakage.[3]

The apparent cap on the allocation of permits to EITE

industries (or activities) is inconsistent with the objective of preventing

carbon leakage. This restrictive allocation is artificially circumscribing the

extent of assistance available under the EITE measure.[4]

This high cost impost poses a real risk of investments moving

offshore, resulting in an economic loss to the Australian economy without any

net environmental benefit as emissions would merely shift elsewhere.[5]

6.7 Other witnesses argued there was a widespread view that the problem of

carbon leakage was greatly overstated.

6.8 As noted by the White Paper, work by the International Energy

Agency suggests there has been little carbon leakage from the EU since their

ETS was introduced.[6]

The Committee asked an expert witness, James Cameron, from the United Kingdom

about the European experience and was told:

We are not experiencing significant competitiveness issues in

any sector, even those most exposed to international competition...On the whole

people do not move their businesses for these reasons...carrying the cost of

carbon is not a significant factor.[7]

6.9 An ABARE study in 2007 found that only about an eighth of the reduced

emissions in Australia may be offset by increased emissions abroad, even if

Australia moved ahead of the rest of the world.[8]

The Department of Climate Change summarised the evidence as follows:

If you look at the experience in Europe, there is very little

evidence to suggest that carbon leakage was a significant problem and, in the

Treasury modelling, there is a suggestion that carbon leakage is unlikely to be

a significant issue.[9]

6.10 A number of witnesses, including to this and other inquiries, have also

questioned the likely extent of carbon leakage:

Those [carbon leakage] arguments need to be robustly

challenged, because they very rarely stand up to scrutiny.[10]

We have a report...by independent experts...which looked in

particular at aluminium and LNG, for example, and concluded that the concerns

about carbon leakage were grossly overstated.[11]

As for carbon leakage, the chance of this happening on any

significant scale is virtually nil. As John Hewson once memorably told me,

"You just don't throw an aluminium smelter in a backpack and take it off

to Indonesia."[12]

Attempts to estimate carbon leakage empirically show

significant variation...some studies report higher results...others point to

minimal carbon leakage occurring.[13]

6.11 Alcoa indicated that, although they were seeking some further assistance

for the most electricity intensive EITE industries, they were willing to work

with the challenge of climate change imperatives:

In terms of the efficiency of operating here in Australia,

these are very, very long-life assets. I think the replacement value of the

assets we have in Australia would be in excess of $20 billion. So they are not

something that we would want to undermine, run down or walk away from easily.

We have been here for more than 40 years. We want to stay for decades to come.

So we will do whatever we can to maintain the competitiveness of the Australian

industry.[14]

6.12 Dr. Richard Dennis from the Australia Institute believes that the

argument that if emissions trading is introduced, there will be carbon leakage

and corporations will exit the country as "absurd" arguing that if

they were that mobile they would have been more likely to leave when our

exchange rate was at US90c.[15]

6.13 The Department of Climate Change notes that the quantum of assistance in

the CPRS can not be justified by carbon leakage arguments:

...there is more support being proposed than is necessary to

deal solely with the issue of carbon leakage.[16]

Transitional adjustment assistance

6.14 As noted above, the Department of Climate Change agreed that the

assistance to EITEs was not based solely on the grounds of climate leakage. The

other goal was described as follows:

...the government is attempting to smooth the transition for

individual firms, rather than just have them take a hit on their profit.[17]

6.15 Other submitters made an argument for transitional assistance:

The draft legislation clearly demonstrates to us an

appreciation of the fact that the Australian economy will require a period of

transition to become a low-carbon economy. There is also a recognition of the

potential competitiveness at threat for some aspects of the Australian

industry. We can also see evidence in the legislation that the government has

considered the emissions trading schemes in other jurisdictions and has looked

to learn from the mistakes and some of the challenges that have been

experienced with those schemes.[18]

The overriding consideration for the AWU has been to ensure

that the EITE industries most exposed to the impacts of the ETS, and least able

to pass on costs associated with participation in the Scheme have the maximum

level of assistance during the transition to an international framework for

emissions trading (which includes both developed and developing countries) on a

true burden sharing basis.[19]

6.16 The transitional assistance is aimed at maintaining business confidence

during the process of adjustment to a carbon-constrained economy and

maintaining energy security.

6.17 The exposure draft legislation proposes to provide free permits to some

EITEs. The permits provided will be based on the industry's historic average emissions

intensity, avoiding penalising individual firms who are lower than average

polluters and retaining an incentive for firms to cut emissions. Assistance

will be linked to production: expanding firms will receive an increased number

of permits and contracting firms will receive fewer permits. A firm which

ceases to operate in Australia will no longer receive permits. To some extent

this part of the CPRS operates like a 'baseline and credit' or 'intensity'

system.[20]

6.18 Trade exposure will be assessed based on either having trade share

(average of exports and imports to value of domestic production) greater than

10 per cent in any year 2004-05 to 2007-08 or a 'demonstrated lack of capacity

to pass through costs due to the potential for international competition'.[21]

Emissions intensity refers to emissions relative to either revenue or value

added, averaged over the lowest four years from 2004-05 to 2008-09.

6.19 Initial assistance will comprise permits to the value of 90 per cent of

the allocative baseline for activities with emissions intensity above 2000 t CO2e

per $million of revenue or 6000 t CO2e per $million of value added.

Permits to the value of 60 per cent of the allocative baseline for activities

with emissions intensity of 1000 to 2000 t CO2e per $million of

revenue or 3000 to 6000 t CO2e per $million of value added.

6.20 The White Paper suggests that, for example, aluminium smelting

and integrated iron and steel manufacturing are likely to qualify for the 90

per cent assistance and alumina refining, petroleum refining and LNG production

as likely to qualify for 60 per cent assistance. If the CPRS is extended to

cover agriculture, it is likely that beef cattle, sheep, dairy cattle, pigs and

sugar cane would qualify for assistance.[22]

6.21 Firms that are able to produce the same quantity of output with fewer

permits than are provided will be able to sell the difference. In effect, they

will receive credit for performance above the baseline. Firms with emissions

above the baseline level will have to buy additional permits.

6.22 The 60 and 90 per cent assistance rates will be gradually scaled down

over time, by 1.3 per cent a year.[23]

However, the Government concedes that 'the share of permits provided to EITE

industries will increase over the first 10 years of the scheme', perhaps to

around 45 per cent.[24]

As other countries introduce broadly consistent carbon pricing schemes, the

assistance programme will be reviewed, but in general five years' notice will

be given of any changes. The reviews may be informed by Productivity Commission

reports on the Scheme's impact on particular industries.

6.23 The argument for concentrating assistance on the EITEs is that other

industries should not be adversely affected:

...if they are not emissions intensive then the costs they will

face will be very low. If they are not trade exposed, that means that all

participants in that industry in Australia will face similar costs and they can

raise prices and pass it on to the community.[25]

6.24 In addition, there will be calculations of the impact of higher electricity

prices resulting from the CPRS on various industries and if required further

permits will be allocated to firms based on this.

6.25 In designing the assistance package, the Government is aware of the need

to avoid subsidies that would place it in breach of WTO rules or undertakings

under bilateral trade arrangements.

6.26 As with all redistributive measures, there will be differing perceptions

of what is fair. The Secretary of the Department of Climate Change put it this

way:

This issue of balance is critical to achieving long-term

sustainability for the scheme. The carbon market we are seeking to create is

created by regulation, and ultimately rests on social consensus. Hence, a sense

of fairness is absolutely critical, not only in its own right but because it contributes

to the longer term policy goal. The value of permits in the emissions trading

scheme can be used to help householders and businesses adjust to a carbon

price. However, we need to bear in mind that assistance that we provide to one

group is assistance that cannot be provided to another.[26]

Criticisms of assistance provided

to EITEs

6.27 There have been two main groups critical of the assistance: companies

who believe they should receive more assistance than envisaged under the CPRS

and those who feel an excessive proportion of the (potential) revenue from the

sale of permits is being returned to large polluters.

6.28 Some examples of the claims from aggrieved companies are:

...all EITE activities should maintain their initial

allocations of permits (ie 60 per cent and 90 per cent) until 80 per cent of

all carbon emissions globally are covered by a comparable carbon constraint.[27]

...trade exposed operations should receive up to 100% of scope

1 permits and up to 100% of permits needed to fully offset costs passed-through

by non-trade exposed industry...remove allocation ‘decay’...[28]

...assistance measures for EITE industries in the CPRS should

be amended to reduce the unbearable cost burden on the domestic steel industry...[29]

...full allocation of permits for Australia's natural gas

exports until competitor countries impose similar carbon costs; and removal of

the 1.3% annual reduction in permit allocations.[30]

6.29 Many industry submissions argue that Australian firms will be unable to

compete internationally if they are required to meet the cost of their carbon

emissions while foreign competitors in the third world are not.[31]

6.30 Arguing that industry should be 'compensated' for the impact of the CPRS

on competitiveness implicitly assumes Australia still has a fixed exchange rate

so that any increase in costs must hurt competitiveness. However:

you would expect a modest exchange rate depreciation as a

result of the introduction of a scheme like this, so those that are not

relatively emissions‑intensive can in fact gain more from the exchange rate

effect than they will face in additional costs.[32]

...the Australian economy as a whole is not affected very much

by whether we compensate trade-exposed industries. One of the things that

happens is that we end up with a lower exchange rate, or a different exchange

rate, so you end up encouraging some other export industries.[33]

The Garnaut approach

6.31 Professor Garnaut has a different proposal for industry assistance which

is elaborated in the Garnaut Review. The key prescription is:

For every unit of production, eligible firms receive a credit

against their permit obligations equivalent to the expected uplift in world

product prices that would eventuate if our trading competitors had policies

similar to our own.[34]

6.32 Professor Garnaut's view is supported by his colleague Dr Jotzo. One of

his criticisms of the CPRS approach is that, unlike that advocated by Professor Garnaut:

...the scheme encourages continuation or indeed expansion of

high emissions activities in Australia that would not be competitive in a world

with comprehensive carbon pricing.[35]

6.33 A criticism of Professor Garnaut's suggestion is that calculating what

price would prevail were foreign countries to adopt differing policies would be

difficult in practice and could be seen as a matter of judgement. Dr Betz, an expert in emissions trading schemes, warned:

The difficulty of this approach is in modelling that... Being

an economist and knowing some of these models I know that they are all based on

an assumption. So the difficulty is in practically implementing it.[36]

6.34 Furthermore, Professor Garnaut's approach would result in no assistance

being provided to those firms whose emissions intensity is higher than the

global average, for example aluminium produced with brown coal fired

electricity.

6.35 Another criticism of giving away free permits to some industries is that

it necessarily raises the burden on the rest of the community:

...shielding trade-exposed industries also has the effect of

redistributing the abatement burden to the non-shielded sectors within

Australia, roughly doubling the carbon price required to achieve the same

abatement and leading to an additional 0.4 percentage point reduction in GDP...[37]

...the substantial share of the total permits is being

allocated for free and that share is set to rise over time without any upper

bound to the share of permits given out for free as total permits. That share

given out for free will be greater the stricter the target is. The upshot is,

of course, that less money is available for assisting lower income households

with higher energy bills and less money is available to invest for government

investment in lower carbon technologies.[38]

Committee comment

6.36 The Committee supports the manner in which the issue of free permits to

companies does not expand with their emissions, which retains incentive to reduce

them. This is not a feature of the assistance provided in some other countries'

assistance schemes.

6.37 The Committee notes that the many assertions by companies of the extent

of carbon leakage have not been matched by much evidence that it will be as

serious a problem as they claim. Payments of assistance can be justified to

guard against carbon leakage and support emissions intensive trade exposed

industries during the transition.

Additional assistance to the coal

mining industry

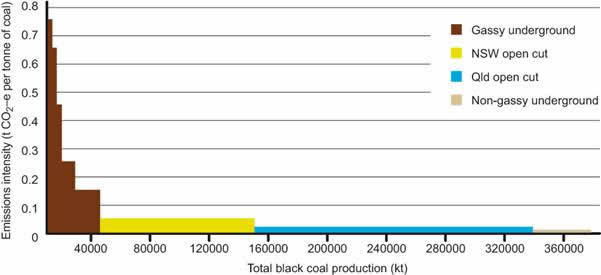

6.38 The great majority of the coal mining industry is not

emissions-intensive. There are a small minority of mines, the so-called 'gassy

mines', which are very emissions‑intensive. (Chart 6.1). The coal mining

industry is unique in having such large within-industry variation in emissions

intensity. This implies:

Were you...to treat them as an emissions intensive trade

exposed industry, you would provide a massive windfall gain to very large parts

of the coal industry and you would not actually deal sufficiently with the

problems that the gassy mines face.[39]

6.39 The Government accordingly decided to treat coal as a special case. This

reasoning was not accepted by the black coal industry's representatives:

Coal is eligible under the white paper rules for 60 per cent

transitional assistance under the arrangements for emissions intensive trade

exposed industries. Coal is well above the 1,000 tonnes of CO2 per

million dollars of revenue eligibility threshold, and we maintain that the

decision to exclude it was a political decision. The coal industry is,

therefore, seeking fair treatment not special treatment.[40]

6.40 The Australian Coal Association argued for additional support:

I will just tell you that $5 billion over five years is our

estimate of the cost of the CPRS to the coal industry. What we are being

provided with is $750 million...we are getting 10 per cent of our costs, LNG is

getting 60 per cent, cement is getting 83 per cent and aluminium is getting 90

per cent. We believe we should be in there at the EITE with 60 per cent.[41]

Chart 6.1: Black

coal mine fugitive emissions intensity (2006-07)

Source: White Paper, p

12-46.

6.41 The black coal industry's response to the issue of 'windfall gains' was

to suggest:

...you just have to slightly adjust the white paper methodology

to allocate the permits mine by mine, according to actual emissions rather than

production, and the problem of windfall gains will immediately go away.[42]

6.42 However, adopting this approach would also mean that coal was being

treated in a different way to other industries. Furthermore, if free permits

were allocated in proportion to actual emissions, it would be eroding the

incentive for coal mines to reduce their emissions intensity. A better approach

is to ensure there are incentives for the gassy mines to introduce the

available or support new abatement technologies, to reduce their emissions by concentrating

and capturing, flaring or using coal mine methane.

6.43 The Government intends to allocate up to $750 million in targeted

assistance to the coal industry, around two-thirds of which will go to 'gassy

mines' to assist in the installation of abatement equipment.[43]

6.44 An industry spokesperson has decried this level of assistance as

inadequate:

The coal industry was...offered token compensation of $750

million...the Government needs to urgently reconsider this decision.[44]

Committee comment

6.45 The Committee believes that a cogent case has been presented to explain

why the form of assistance provided to the more homogenous EITE industries

would have perverse effects in the coal industry due to the wide variety in the

emissions intensities of individual mines. The proposed assistance is more

appropriate than the suggestion of treating coal as an EITE industry. The

application of the EITE thresholds broadly across the coal industry would put a

disproportionate burden on other energy consumers including small business and

households, including pensioners and low income households.

Additional assistance to industries

producing lower emissions fuels and products

6.46 The liquid natural gas (LNG) industry made the point that natural gas is

a cleaner burning material than other fuels. Although the industry uses energy

to convert natural gas to LNG in Australia (thus increasing emissions locally),

they argue that the CPRS does not take into account that LNG has the capacity

to reduce greenhouse gases globally. LNG is 100% exported. The industry

recognises that the industry has been given EITE status (at the 60% level) but

put the case they should receive increased transitional assistance or complete

exemption from the scheme on the grounds that they lower global emissions, will

generate employment or other benefits to Australia and are highly trade exposed:

LNG has been characterised as an anomaly within the emissions

trading scheme design. Although producing LNG is emissions intensive and adds

to greenhouse gas emissions in Australia, natural gas makes a substantial net

contribution to reducing global greenhouse gas emissions. As the world

inevitably shifts to a preference for cleaner burning fuels, the substantial

strategic value of Australia’s natural gas assets can only increase. APPEA

therefore recommends that the draft Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme Bill 2009

be amended to ensure that the LNG industry does not face any costs associated

with a domestic emissions trading scheme while ever our competitors and our

customers are not subject to similar imposts.[45]

6.47 There are also proposed LNG projects that will be more emissions

intensive than the North West Shelf gas fields that the CPRS will use as the base

to calculate the rate of EITE assistance for other projects.

Committee comment

6.48 The Government has set up an expert advisory committee, chaired by

Mr Dick Warburton, to provide advice on arrangements for EITE assistance.[46]

The Warburton Committee will provide advice on activity definitions and the

delineation of boundaries around each activity for the purposes of EITE

assessment. This will enable the LNG industry to put a case for individual

projects.

Assistance to electricity

generators

6.49 The Government will assist electricity generators through the

Electricity Sector Adjustment Scheme (ESAS), which will provide an amount of

free permits, worth about $4 billion over five years.

6.50 This assistance can not be justified to avoid carbon leakage as the

power generators serve the domestic market and do not compete with overseas

companies. They should be substantially able to pass on the cost of permits to

customers (who in the case of low income households will be able to pay out of

the assistance payments), but there may be some reduction in the value of their

assets.

6.51 The Energy Supply Association of Australia argue that the $4 billion in

assistance is not enough, and pointed to figures suggesting more than twice

that amount:

The proposed $3½ billion of assistance is insufficient and

considerably lower than the consensus of modelling reports, which include two

sets of government modelling reports, which suggest at least $10 billion of

assistance is required in the first 10 years.[47]

Insufficient assistance is likely to result in an immediate

reduction in generators’ credit ratings and/or breaches of financial ratios

(due to the immediate loss in asset value). At the very least, a number of

generators would be unable to meet the prudential requirements of their Australian

Financial Services Licence and would be unable to trade.... This may result in a

series of financial defaults throughout the market.[48]

6.52 No other submissions shared this view of steeply declining asset values.

In the White Paper, the Government concluded that:

.....given the advice of the energy market institutions

regarding the likely impact on the energy market, and the provision of

assistance to the most affected generators through ESAS, it is very unlikely

that the actions of creditors will pose a risk to energy security, as it will

not be in their interests to take aggressive enforcement action, or to withdraw

an asset from the market when prices would justify continued generation.[49]

6.53 The CPRS bill commentary notes that, in regard to ESAS assistance, the

CPRS:

...will impose a new cost on fossil fuel-fired electricity

generators...relatively emissions-intensive generators are likely to face a

greater increase in their operating costs than the general increase in the

level of electricity prices...[and] lose profitability...if investors consider that

the regulatory environment is riskier...all investments in the sector could face

an increased risk premium.[50]

6.54 Some commentators have criticised the proposed assistance as unjustified

handouts:

There is no risk and there is no threat to those industries.

In fact there is no doubt that if you did due diligence before you purchased

such an asset, you would find that the due diligence suggested there was a risk

in buying these assets of a significant carbon price. And given that most of

the coal fired power stations in Australia have changed hands since that became

obvious, the notion that anyone who bought those assets has been taken by

surprise I think suggests that other people have failed in their duties. So to

give billions of dollars to those groups is, I think, an egregious waste of

taxpayers’ money.[51]

...with the electricity sector in both Victoria and New South

Wales, if you did not see this coming, then you were asleep; if you did not see

this coming, you were not doing your due diligence. In the case of Victorian

generator owners, you were both greedy and silly.[52]

Committee comment

6.55 There is a legitimate concern that the provision of power to households

not be disrupted during the transition to less carbon-intensive energy supplies.

It is noted that no renewable energy sources are currently able to provide

baseload power or rapidly increase production to meet peak demands. Therefore

it is necessary that industry assistance is provided to ensure energy security

whilst the renewable energy sector develops.

Climate Change Action Fund

6.56 The Fund will receive $2.2 billion over five years which will be

deployed to smooth the transition. Among activities to be supported from the

Fund are informing people about the operation of the Scheme, assisting small

businesses and community organisations invest in more energy efficient

equipment, competitive grants for low emission technologies, structural

adjustment for workers and communities adversely affected by the Scheme and

special assistance to gassy coal mines.

6.57 A stakeholder Consultative Committee will be formed in 2009 to advise on

the design of the Fund.

6.58 Some witnesses thought the fund would play an important role:

...if used wisely, the Climate Change Action Fund may be as

important as the carbon price...[it should be increased and used] to deliver an additional range of

business engagement and emission reduction programmes.[53]

Support for our workers, communities and regions will also be

vital and that the full weight of the Climate Change Action Fund be devoted to

this end. The CCAF may need to be supplemented if necessary (beyond $200

million) to ensure adequate coverage in the context of the transition during

the GFC and to share the benefits of new infrastructure investment and industry

assistance measures.[54]

6.59 It may be too soon to be definitive about its operations:

the details of the...climate change action fund are not there.[55]

The precise details of that scheme have not been finalised;

there are consultations going on.[56]

6.60 There were various suggestions made about priorities for the fund. The

Australian Geothermal Energy Association suggested some modest allocations to

help renewable energy companies demonstrate their commercial viability by

building pilot plants.[57]

The Energy Users Association of Australia thought it could fund measures to

encourage energy efficiency.[58]

The Australasian Railway Association called for targeted rail investment and

programmes to inform transport choices.[59]

The impact on, and assistance for, households and small business

6.61 About half the revenue raised from selling permits will be dedicated to

assisting households.

6.62 Assistance measures for households will be initially based on an assumed

carbon price of $25 a tonne. This will increase the average household's

electricity bill by around $4-5 per week and gas and other household fuel bill

by $2 per week (assuming no behavioural response).[60]

6.63 The total impact on the CPI is estimated at 1.1 per cent in 2010-11.[61]

This is also the average increase in prices facing the average household. The

impact will vary across households depending on their expenditure patterns,

from 1.4 per cent for the average low-income sole parent or pensioner household

to 0.9 per cent for the average high‑income single income childless

household.[62]

6.64 This is an upper bound for the impact on household budgets, as consumers

'shift household consumption towards goods that become relatively cheaper

because they require fewer emissions to produce'.[63]

6.65 Benefit recipients will automatically receive assistance for these price

increases as the benefits are indexed. Indeed, given the possibility of

substituting away from the products that have become dearer, they will be

overcompensated by the indexation arrangements.

6.66 In addition, the Government's plan involves additional payments to

pensioners, seniors, carers and people with disabilities of around 1½ per cent.

There will also be additional support to low- and middle-income households,

through increases in the low income tax offset, family tax benefits and

dependency tax offsets and a transitional payment of $500 for some low-income

singles.

6.67 Assistance to households is premised on the notion that, while most

households will be able to adjust their behaviour to minimise the impact of the

scheme on their standard of living, those who have a low capacity to absorb or

avoid the effects of the scheme should be provided with direct assistance.[64]

The proposed assistance comprises:

-

pensioners, seniors, carers and people with disability will

receive additional support, above indexation, to fully meet the expected

overall increase in the cost of living flowing from the scheme;

-

other low–income households will receive additional support,

above indexation, to fully meet the expected overall increase in the cost of

living flowing from the scheme;

-

around 89 per cent of low-income households (or 2.9 million

households) will receive assistance equal to 120 per cent or more of their cost

of living increase;

-

middle–income households will receive additional support, above

indexation, to help meet the expected overall increase in the cost of living

flowing from the scheme. For middle–income families receiving Family Tax

Benefit Part A, the Government will provide assistance to meet at least half of

those costs;

-

around 97 per cent of middle-income households will receive some

direct cash assistance. Around 60 per cent of all middle-income households (or

2.4 million households) will receive sufficient assistance to meet the overall

expected cost of living increase; and

-

motorists will be protected from higher fuel costs from the

scheme by ‘cent for cent' reductions in fuel tax for the first three years.[65]

6.68 Additional household assistance is provided not only to ensure that

those who can least afford the cost of living increase are not disadvantaged

but also to ensure additional support through the introduction of energy

efficiency measures and consumer information to help households take practical

action to reduce energy use and save on energy bills.[66]

This should enable households, particularly those that also modify their

behaviour, to pay for energy saving appliances and equipment.

6.69 Furthermore, the Government will bring forward the indexation around the

time of the CPRS' introduction so that the additional payments are available to

meet additional energy costs at the time the scheme commences.

6.70 The Australian Council of Social Service is guardedly satisfied with the

proposed assistance:

... whether or not the compensation proposed is sufficient. We

are concerned that it may not be but we are relying on Treasury modelling.

Other modelling suggests that the flow-through to cost of living will be higher

than 1.1 per cent, particularly for certain kinds of households, notably single

pensioners and sole parents. But we are going with the Treasury modelling and

with the promise of reviews and indexation subsequently.[67]

Committee

comment

6.71 The Committee believes the assistance programme for low income

households strikes the right balance between ensuring they are not

disadvantaged but retaining incentives to lower greenhouse gas emissions.

Furthermore, additional assistance than what is required will support

households to invest in energy efficient measures for their homes.

Transitional fuel tax offset

6.72 The impact of the CPRS on petrol prices will be offset by cuts in other

fuel taxes.

6.73 A transitional offset is not the same as temporarily excluding transport

emissions from the scheme, for a number of reasons. First, coverage should still

provide a signal to motorists that carbon prices will affect their long-term

transport decisions.

6.74 Second, scheme coverage means that fuel suppliers will be required to

participate fully in the scheme, including establishing the administrative

mechanisms required to determine and allocate liabilities for liquid fuels.

6.75 Further, coverage ensures that transport emissions are included within

the scheme cap. If transport emissions grow, more abatement will be required in

other sectors of the economy.

6.76 As a higher fuel price leads people to buy more fuel-efficient models

when they replace cars, and prefer to live nearer to public transport, the

long-run response to an increase in fuel prices is much more than the

short-term response.

We find price elasticities of -0.13 (short term) and -0.20

(long term).[68]

The short-term elasticity is usually considered as about

negative 0.1, and the long-term elasticity is more in the realm of minus 0.3 to

minus 0.5... [69]

The green paper last year by the Bureau of Infrastructure,

Transport and Regional Economics... seemed to indicate that short-run elasticity

is around 0.1 to 0.2 and long-run elasticity—perhaps five to 10 years out—is

around about 0.4 to 0.5. [70]

Committee comment

6.77 The Committee regards carbon leakage and the need to smooth the

adjustment process to a low-carbon economy as good reason for some government

assistance to industry. It is also important that low income households are not

unduly disadvantaged. The CPRS structures these assistance measures in a manner

that retains incentives to take measures to reduce emissions of greenhouse

gases.

6.78 The committee notes the persistent advocacy of industry groups for

further assistance under the scheme. On the other hand other stakeholders have

criticised the scheme for being too generous to polluting industries.

6.79 The committee believes that the Bill has the balance right, retaining

strong incentives to reduce carbon intensity while enabling important economic

assets to remain viable throughout the adjustment. This is fundamentally

important to protecting jobs and enabling jobs in the green economy to grow.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page