Chapter 4

The renewable energy target as a complement to emissions trading

The RET and an ETS

4.1

It is commonly argued that an effective emissions trading scheme will

provide emissions mitigation at lower cost than a RET with a binding target. If

the RET is non-binding, then it just results in wasted administrative and

compliance costs:

...reductions in emissions of greenhouse gases should be

achieved at the lowest possible cost. Ai Group therefore supports a broad-based

market approach in the form of a well-designed ETS to drive lowest-cost

emissions abatement across the whole economy. If the proposed CPRS is passed,

with appropriate amendments to assist affected industries during the transition,

there will be no need for the RET at all.[1]

If you were comfortable with all of the parameters of an ETS

and you thought that the targets were right and other dimensions of the scheme

were right, I do not think you could make a case for the renewable energy

target. It would be redundant. Any case for the renewable energy target depends

on your not thinking that the ETS is defined in a way that will do the job. You

do not think the targets are ambitious enough or you think something else is

wrong with it...Is the renewable energy scheme an economically efficient way of

reducing emissions? No, the emissions trading scheme is more efficient.[2]

An MRET operating in conjunction with an ETS would not

encourage any additional abatement, but still impose additional administration

and monitoring costs. To the extent that the MRET is binding (which is its

purpose) it would constrain how emission reductions are achieved — electricity

prices would be higher than otherwise and market coordination about the

appropriate time to introduce low-emissions energy technologies would be

overridden. If it was non-binding, it would simply increase administrative, compliance

and monitoring costs. Moreover, it would also help to foster a perception that governments

are amenable to interfering with the least cost abatement objective of the ETS.

This could encourage other potential beneficiaries to seek special programs

that neither increase abatement nor reduce its cost.[3]

4.2

The bill amends the existing act so that instead of aiming 'to reduce

emissions of greenhouse gases', the goal is now 'to reduce emissions of

greenhouse gases in the electricity sector'. This may be an acknowledgement

that under the CPRS it will be the targets set in the CPRS that determine total

emissions and reducing them in the electricity sector 'frees up' permits for

other sectors to increase their emissions.

4.3

One submitter wanted this interaction made more explicit:

The Committee should recommend that this Bill mandate full

disclosure in RECs transactions such that householders are properly advised

that when they sign across RECs or Solar Credits they are displacing other

renewables already required by law, achieving zero additional renewable energy

and zero reduced emissions for Australia.[4]

4.4

Whether the RET will be binding will depend on how strict is the target

under the CPRS. Treasury told the Committee that if the CPRS target for 2020

emissions is a five per cent reduction from 2000 levels, then renewable energy

accounts for only about 10 per cent of total electricity sources in 2020.[5]

Under this modest CPRS, the RET doubles the usage of renewable energy.

4.5

With a more ambitious target of a 25 per cent reduction in emissions, it

is projected that the CPRS would lead to almost 25 per cent of Australian

electricity generation coming from renewable energy in 2020.[6]

This would exceed the proportion set by the RET, so in this sense the RET might

be regarded as redundant.

4.6

Some witnesses did not believe the case had been made for any RET:

...the proposed expansion of the renewable energy target is

occurring without the evidence of market failure.[7]

4.7

The Clean Energy Council responded:

...we do not have a full carbon price globally which would make

these investments unequivocally beneficial... We are trying to discover what

these technologies can do and at what scale. We know that they can do a lot; it

is just a question of how much, and how much they will cost and how quickly and

how big they can deploy. You can wait for the market to do that but, without

signals, the market may take a generation to actually start answering those

questions. There is a time imperative in the current advice on climate science,[8]

The RET as an industry development measure

4.8

A RET may be justified as a complement to an emissions trading scheme if

there is an industry development objective. The Department of Climate Change

explained it as follows:

The expanded RET scheme is a key transitional measure

accompanying the proposed CPRS. Whereas the CPRS will help bring renewable

technologies into the market over time, the national RET scheme will accelerate

deployment of renewable energy technologies by providing a guaranteed market

for renewable energy. The RET will conclude in 2030, at which time the CPRS is

expected to be the primary driver of renewable energy deployment...As the carbon

price increases, you would not need a renewable energy target to make the

renewable energy cost competitive because the pure carbon price itself from the

CPRS makes it competitive. That is why the RET is explicitly a transitional

measure...[9]

4.9

This is how many witnesses and submitters see the RET:

The idea of a renewable energy target is an industry

development measure to drive and accelerate deployment and development of these

technologies ahead of any carbon price...[10]

...the purpose of a renewable energy target is...to provide for

industry development.[11]

...we view the RET as a transitionary measure which is one part

of a package of policies that will stimulate investment in renewable

technologies.[12]

While the objective of the CPRS is to bring down Australia’s

emissions, the purpose of the RET is to build the energy industries Australia

requires to deliver this sustainably.[13]

4.10

The Minister has explained the rationale for the RET in the following

terms:

The policy point of the renewable energy target is to bring

on investment into renewable technologies earlier than would otherwise have

been. It is the case that there are a number of technologies that have not yet

been commercially deployed. There are technologies which are already being

utilised. This is a substantial ramp-up in the target, in part to provide a

market incentive for the private sector to invest in renewable energies.[14]

4.11

The argument for industry development is that renewable energy is an

industry of the future and Australia is lagging behind. Greenpeace suggest:

There is not a single wind turbine anywhere in Europe that

was built as a result of their emissions trading scheme—not one. They were

built as a result of the renewable energy targets and feed-in tariffs and other

direct regulatory policies.[15]

4.12

Another perspective is that the RET seeks to accelerate the take-up of

renewable power rather than prop it up artificially indefinitely. Professor

Wills offers this comparison:

...the IT industry in the 1980s started without government

intervention. It started because there was a perceived demand for the

technology, and businesses paid at the very expensive end of the technology

curve in the eighties for IT equipment that over the last 25 years has become

very affordable and very mainstream. I have no doubt that the renewable energy

industry, if left alone, would do the same thing over the next 25 to 30 years.

But the challenge for us here, today, in 2009, is that we want technologies

that will reduce emissions today and not in 20 or 30 years time. So the problem

for us is that we actually have to pay the premium price for a service that

cannot really be delivered in any other way at this point—that is, emissions-free

energy.[16]

Encouraging diversity of renewable energies

4.13

A concern with the RET is that it may not encourage development of a

diverse range of renewable energies, but lead to a concentration on whichever

is viewed as currently the cheapest, probably wind:

The Bill needs to provide support for new and emerging

technologies which may be less competitive against the mature lowest-cost

offering today but which offer longer term potential in the market. This point

was made in the Stern Report and expressed as “While markets will tend to

deliver the least‑cost short-term option, it is possible they may ignore

technologies that could ultimately deliver huge cost savings in the long term”.

“Policy should be aimed at bringing a portfolio of low-emission technology options

to commercial viability.”[17]

...the value of the RECs to the business case of projects built

in the first few years of the scheme may result in projects offering an early

and extended return getting off the ground against projects ready for

development in the middle of the scheme with higher up front development costs

ultimately producing cheaper or, overall, a more cost effective energy over the

lifetime of the project.[18]

4.14

In particular, the geothermal industry is concerned that the RET will

encourage the more mature renewable energy industry, such as wind, and be

phased out before it can assist emerging renewable energies:

...the incentives offered under the scheme might not be

available by the time geothermal generation projects and other emerging

renewable energy technology projects were ready to come onstream... the RET

scheme will in fact defer the development of geothermal energy projects in

Australia, as the incentives it provides will encourage the development of the

existing technologies at a level that will effectively lock out geothermal

energy projects.[19]

4.15

This criticism may be overstated. The Department of Climate Change

pointed out:

...the modelling indicates a reasonable diversity of renewable

energy at 2020 including a substantial amount of geothermal.[20]

Banding

4.16

A desire to ensure diversity of renewable energy sources has led to some

calls for requiring minimum contributions from particular renewable sources,

sometimes referred to as 'banding', 'tranches' or 'carve-outs':

...amending the legislation to create specific carve-outs for

emerging technology...would essentially ensure that a sufficient proportion of

the RET would be reserved for emerging renewable technologies when they are

expected to be developed.[21]

4.17

Professor Andrew Blakers calls for a specific tranche of 15,000 GWh for

solar energy (photovoltaics and solar thermal energy) which he argues has the

most long‑run potential:

Solar energy will eventually dominate clean energy markets –

its immense advantages are clear. However, another decade will be required to

get the cost of solar energy down to the 12c/kWh mark where it will

successfully compete at large scale with wind.[22]

4.18

It has been pointed out that the scheme proposed in the United Kingdom

encourages a diversity of sources:

...the United Kingdom‘s banded scheme, which proposes awarding

the equivalent of a quarter of a Renewable Energy Certificate per megawatt hour

of electricity to established technologies such as landfill gas, one

Certificate for wind and two for an emerging technology like solar thermal.[23]

4.19

A variant of this approach has been suggested by the Australian

Geothermal Energy Association:

...it is quite a good proposal that merging technologies have

to generate 0.75 per cent of a megawatt hour to get a REC and that existing

technologies have to generate 1.25 megawatts to get their REC, and that way you

end up with basically the same cost across the scheme.[24]

4.20

Another approach to the same end is the use of 'boosters':

For instance a “Solar Booster” would provide additional value

above both the market energy cost and the REC market value for energy produced

by certified and contracted solar technology. A Booster would be a fixed,

designated payment per Megawatt-hour provided as an ‘after market’ payment. The

Government would have the control and ability to establish Boosters tailored to

the specific needs of a new emerging technology...[25]

4.21

These approaches have been rejected by many submitters, notably

including those involved with wind energy, as 'picking winners' rather than

relying on market forces:[26]

The carve outs have been used internationally in a number of

schemes, for instance in the UK, and they have not really worked very well.[27]

...we cannot support technology carve outs as proposed by some

organisations for emerging technologies. Our view is that the commercialisation

path for those technologies, geothermal, solar thermal etcetera should be

advanced through appropriate and targeted policy mechanisms so that in time

they can operate under a renewable energy target framework or indeed a CPRS in

the longer term.[28]

...introducing banding into the RET will reduce the efficient

operation of the market by bringing forward more expensive technologies, adding

to the overall cost of the measure; and risk constraining the development of

industries that are close to commercially viable.[29]

...there will be stakeholders who want to micro-manage the

energy market in an attempt to gain some advantage for the most fashionable and

exciting form of power generation, even though it might be many years away from

being ready for commercial-scale deployment. Their proposal...is a recipe for

endless government involvement in a market that performs best without it.[30]

Impact of banking

4.22

The banking of RECs (described in paragraph 2.9) may also hamper the

development of a range of technologies by encouraging overproduction early on

using the currently cheapest technology rather than technologies which may

become cheaper in later years:

...this banking distorts the market. It allows you to sit on

RECs that you have created and acquit them later...there is a huge incentive to

start doing that from 2010, when you get RECs, therefore, from your first

project, for 20 years of the scheme.[31]

Unlimited banking creates an incentive to stockpile Renewable

Energy Certificates by investing in wind power and more mature renewable energy

sources potentially at the expense of solar thermal.[32]

Feed-in tariffs

4.23

Another way of allowing differentiated tariffs for different

technologies is to have a gross feed-in tariff (FIT).

4.24

A 'feed-in tariff' refers to a premium rate paid for electricity fed

back into the electricity grid from a renewable electricity generation source.

The most commonly discussed source is a solar panel on the roof of a home which

may generate more power than is consumed within the home. However, FITs can

also be applied to large scale commercial projects. A net feed in

tariff, also known as export metering, pays the provider only for surplus

energy they produce; whereas a gross feed-in tariff pays for each kilowatt

hour produced by a grid connected system, whether it is consumed by the

producer or fed into the grid.

4.25

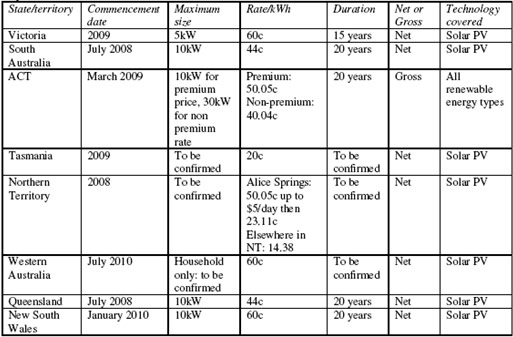

State governments currently have or have planned such tariffs (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1: Feed-in

tariff schemes (as at June 2009)

Source: Greg Buckman, Submission

21, p 12.

4.26

A number of witnesses and submissions called for a national gross

feed-in tariff.[33]

... BP Solar certainly has been advocating and lobbying hard

for the adoption of a gross feed in tariff across all of Australia’s jurisdictions

with the inclusion of the commercial and industrial sectors...Gross feed in

tariffs have now been adopted in more than 45 countries and over 18 states and

provinces around the world...Feed in tariffs have been proven as the cheapest and

the fastest way of deploying solar PV into the marketplace and we would

certainly want to see a gross national feed in tariff in place before the solar

credit scheme winds up by the year 2015.[34]

Finally, with almost 30 years of experience directly within

the Solar PV industry, RFI believe that the implementation of a Gross National

Feed-in Tariff (FIT) is the natural and required market stimulation model to

provide certainty, value and benefits to all parties within the renewable

energy sector. This is a proven and well known model internationally and one

which has been described in detail to government and proven to provide the

positive benefits of renewable energy over the short to medium term. The Gross

FIT has turned several European countries into world leaders in the field of

Renewable Energy and we believe the time has come for Australia to adopt this

initiative as a significant tool in the drive for greater adoption of renewable

energy in our country.[35]

A common factor amongst the world’s strongest renewable energy

markets is the use of “Feed-in Tariffs” for driving the uptake of renewable

energy.[36]

4.27

Some submissions want business to be able to participate:

In stark contrast to Australia, solar power is being

successfully promoted in many countries to business through gross feed-in

tariff mechanisms. Feed‑in tariffs in virtually every country are open to

businesses to participate and profit from investing in solar power production.[37]

4.28

The Clean Energy Council preferred a RET over a feed-in tariff using

arguments reminiscent of those for preferring an emissions trading scheme over

a carbon tax:

A feed-in tariff...sets the price and then the volume is set by

the market, whereas a renewable energy target sets the volume and then lets the

market set the price.[38]

4.29

The Department of Climate Change noted:

A Renewable Energy Target (RET) and feed-in tariff are

alternative policy mechanisms for promoting renewable energy uptake often

designed to meet similar objectives. A RET sets the quantity of renewable

energy and allows for a range of cost effective technologies to be deployed. A

RET does not specify the precise rate of support required for each technology.

In contrast, a feed in tariff provides a certain amount of support for

specified technologies which is set in advance for a future period of time.

Given the uncertainty and complexity in setting prices for each technology,

feed in tariffs could lead to more or less of certain technologies being

deployed if the price set does not accurately reflect the amount of support required

by that technology.[39]

4.30

Concerns have been expressed about equity aspects of feed-in tariffs

aimed at households:

It is deeply inequitable, because the people who can afford

it tend to be people with some reasonable amount of money. Here [in the ACT] it

is a gross tariff of 50c a kilowatt hour, which is pretty good. It is about

four times what we sell our retail tariff for normal energy. That cost, of

course, has to be borne by the whole of the community, including the poorer

people of the community who spend 15 per cent of their budget on energy as

against the better off people who spend five per cent of their budget on

energy. There is an equity issue there and, also, it is very expensive.[40]

4.31

There was also claims that it provides less incentive for innovation:

...if you are too generous with the feed-in tariff, you build

fat into the technology and the technology becomes lazy and does not strive to

continually improve its performance and, if you underset the rate of the

feed-in tariff, then you do not get any project development.[41]

4.32

One submitter suggested that only households buying 100 per cent green

power should be eligible to be paid a high price under a feed-in tariff.[42]

4.33

COAG decided in November 2008 not to implement a national feed-in

tariff.

Sunset clauses

4.34

Another means of encouraging diversity is to restrict the period for

which projects can earn RECs:

...sunset clauses so that projects can only earn renewable

energy certificates for a period of years. That will also help us address

issues of promising but still emerging renewable technologies such as hot rock,

which might be coming into play later than some of the early technologies.[43]

Other measures supporting diversity

of renewable energy

4.35

In the 2009-10 Budget, the Government announced the $4.5 billion Clean

Energy Initiative. This includes;

-

Australian Solar Institute to support research into solar

technologies ($0.1 billion);

-

Solar Flagships programme to create an additional 1,000 megawatts

of solar generation capacity ($1.5 billion);

-

Australian Centre for Renewable Energy to promote the

development, commercialisation and deployment of renewable technologies ($0.5

billion);

-

Renewables Australia to support technological research and

bringing it to market ($0.5 billion); and

-

National Solar Schools programme ($0.5 billion).[44]

4.36

Some of these programmes complement the RET to develop renewable

technologies that may not be viable in the short term but have long term

promise:

...the renewable energy target effectively deploys the lowest

cost renewable energy currently available at the time it is rolled out. The

government expenditure based programs are targeted at areas that would be

likely to be more expensive than the current ones picked up on the renewable

energy target, but you would expect there would be more novel or innovation

benefits from assisting those technologies so that you have a broader suite of

renewable energy technologies.[45]

Committee view

4.37

The Committee would like to see a range of renewable technologies develop.

Renewable Energy Targets have been adopted internationally to provide

transitional assistance to renewable energy technologies, where a purely market

based approach would not result in sufficient investment and take up in the

short term. However the committee is not attracted to the idea of 'banding',

which it regards as excessively prescriptive. It welcomes the support for

diverse renewable technologies contained in the programmes under the Clean

Energy Initiative.

4.38

The Committee understands the geothermal industry's concerns about the

impact of unlimited banking of RECs, but also sees the merit in terms of

flexibility of allowing for some banking.

Recommendation 3

4.39 The Committee recommends that the banking of renewable energy

certificates be assessed as a part of the 2014 review.

The Spanish experience

4.40

A paper on the Spanish experience by Dr Alvarez concludes that promoting

renewable energy is 'terribly economically counterproductive', and that:

...since 2000 Spain spent €571,138 to create each “green job”,

including subsidies of more than €1 million per wind industry job....2.2 jobs

destroyed for every “green job” created...Principally, the high cost of

electricity affects costs of production and employment levels in metallurgy,

non-metallic mining and food processing, beverage and tobacco industries.[46]

4.41

There seem to be quite a few important differences between the Spanish

scheme of subsidy payments to nominated renewable industries and the more

flexible RET in Australia. Alvarez points to some design flaws, such as

arbitrary limits on eligible plant size that increased costs and are not part

of the Australian scheme. He also refers to low interest rates sparking a

speculative boom in the economy as a whole, not just in the renewable energy

sector. Also as a member of the eurozone, Spain effectively has a fixed

exchange rate.

4.42

The study has a short-term focus, basing its conclusions on employment

outcomes in a period of global recession. It does not refer to the long-term

employment benefits of Spain having installed energy sources with low marginal

costs. Not is there any reference to the benefits of accelerating investment in

renewables to fight climate change effectively. The company he cites as having

been driven away from Spain by the higher energy prices, Acerinox, opened a new

plant in the US, which is of course now introducing its own measures which will

increase the relative price of power.

4.43

The Alvarez study has been critiqued within Spain by Portillo et al, of

the Reference Centre for Renewable Energies and Employment, who claim it

misrepresents the Spanish system, ignores relevant influences such as past

subsidies for fossil fuels, and omits the beneficial effect wind energy has had

on electricity prices.[47]

4.44

The Spanish Government is scathing about the study, describing it as:

...based on a simplistic, reductionist and short-term

view...[which] contradicts most of the previous studies carried out by different

researches...[48]

4.45

Alvarez's estimates of 'green jobs' created are much lower than other,

credible, estimates.[49]

4.46

The Department of Climate Change drew the Committee's attention to how

the Spanish Government:

...questions the economic methodology employed by the study,

and...the focus on short-term economic outcomes at the expense of the medium to

long-term impacts of lowering the carbon intensity of electricity production.[50]

4.47

The Department's own views are also critical:

From preliminary analysis of the Alvarez report by DCC, the

report uses a simplistic equation to estimate the amount of jobs that would

otherwise have been created if the ‘green job’ was not created. This is

measured through a simplified equation that compares the subsidy to renewables

against the average productivity of a worker.[51]

4.48

The Australian Conservation Foundation has also critiqued the article

and concluded:

The study relies on a flawed methodology, unsourced data and

use of secondary sources that are often not cited. The study is an advocacy

document, written in English, which was primarily directed at influencing the

US political debate.[52]

4.49

There are doubts about the objectivity of the author:

...he has affiliations with a number of climate sceptic

conservative organisations—including the Centre for the New Europe which has

accepted funding from Exxon Mobil—has spoken to the Heartland Institute on many

occasions, heads up a small Spanish free-trade think tank and is a climate

sceptic himself...[53]

4.50

The Institute of Public Affairs cites Alvarez' work, but then makes a

more extreme point than Alvarez himself. Dr Moran says that Spain's promotion

of renewable energy 'has contributed to an economic disaster' and was 'a

significant factor' in Spanish unemployment rising from around the OECD average

to the highest rate – 18 per cent.[54]

4.51

Mr Comley from the Department of Climate Change is sceptical about

drawing a link between use of renewable energy and high unemployment in Spain:

I would find it quite implausible that those sorts of

policies would have any sort of correlation of that type with unemployment. I

suspect in the Spanish case that the ending of a construction boom, associated

with a range of factors within Europe, is likely to be of greater significance.[55]

4.52

It has also been pointed out that the Spanish unemployment rate was 25

per cent before the renewable energy policy was introduced.[56]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page