Chapter 2

The case for change

2.1 In recent years the science of climate change has become increasingly

well‑understood due to the efforts of the world's scientists. As public

interest and debate over the issue has grown, many of the important concepts

and debates in climate science have effectively become accepted by the mainstream

scientific community. It is interesting to note in this respect that Australia's 2007 election has been described as 'the first election in history in which

climate change...was among the top three voting issues'.[1]

The greenhouse effect

2.2 Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a gas that occurs naturally in the

atmosphere. It and other greenhouse gases absorb and re-radiate heat from the

Earth's surface, which maintains the Earth's surface temperature at a level

necessary to support life.[2]

2.3 This 'greenhouse effect' involves the sun's light energy travelling

through the Earth's atmosphere to reach the planet's surface, where some of it

is converted to heat energy. Most of that energy is re-radiated towards

space—however, some is re‑radiated towards the ground by the greenhouse

gases in the Earth's atmosphere.

2.4 Human activities such as burning fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas),

agriculture and land clearing release large quantities of greenhouse gases (particularly

CO2, nitrous oxide and methane) into the atmosphere, which trap more

heat and further raise the Earth's surface temperature.

Global warming

2.5 Since modern measurements began in the late 1800s, global average

surface temperature has increased by around 0.7ºC – 0.8ºC.

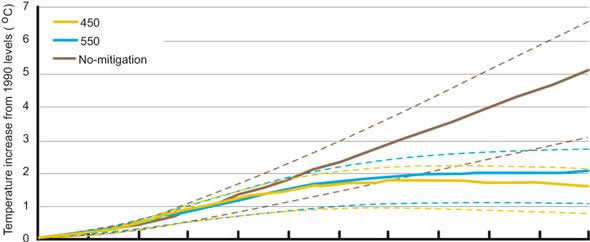

2.6 The Garnaut Review's projections for temperatures if nothing is

done, or if CO2e is stabilised at 450 and 550 parts per million, are

shown in Chart 2.1. Stabilisation at 450 ppm, which Garnaut concluded was in

Australia's interests, requires significant reductions in emissions starting

very soon.

Chart 2.1: Global average

temperature outcomes for three emissions cases 1990-2100

Note:

Temperature

increases from 1990 levels are from the MAGICC climate model (Wigley 2003). The

solid lines show the temperature outcome for the best-estimate climate

sensitivity of 3ºC. The dashed lines show the outcomes for climate

sensitivities of 1.5ºC and 4.5ºC for the lower and upper temperatures

respectively. The IPCC considers that climate sensitivities under 1.5ºC are

considered unlikely (less than 33 per cent probability), and that 4.5ºC is at

the upper end of the range considered likely (greater than 66 per cent

probability).

Source: R Garnaut, The Garnaut Climate

Change Review: Final report, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 92.

Scientific consensus on climate change

2.7 An overwhelming majority of the world's scientists, particularly climate

scientists, have concluded that greenhouse gases are the main factor

contributing to climate change since the 1950s.

2.8 The pre-eminent international body studying climate change is the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The IPCC has concluded that

warming of the climate system is unequivocal;[3]

and, with a very high confidence (at least a 9 out of 10 chance of being

correct) that the increase in global average temperature since the mid‑20th century

is due to anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations. In a 'business as usual'

world the IPCC's best estimate is that average temperatures will rise four

degrees by 2100.[4]

2.9 As an exercise in global scientific consensus the IPCC is unparalleled,

and the IPCC 2007 report is 'probably the most scrutinised scientific document

in the world'.[5]

John Holdren, now President Obama's chief science adviser, said of its

conclusions:

They are based on an immense edifice of painstaking studies

published in the world's leading peer-reviewed scientific journals. They have

been vetted and documented in excruciating detail by the largest, longest,

costliest, most international, most interdisciplinary, and most thorough formal

review of a scientific topic ever conducted.[6]

2.10 The IPCC makes clear that there is a range of uncertainty around the

projections. Prudent risk management would balance the risk of doing nothing

when the climate scientists are right – which would involve very severe and

irreversible damage to human welfare – against the outcome if action is taken

unnecessarily, which would just mean that remaining fossil fuel supplies would

last longer.

Impacts on Australia

2.11 The IPCC has predicted with high confidence (an 8 out of 10 chance of

being correct) that without mitigation, by 2100 a temperature rise of over four

degrees in Australia would lead to water security problems, and risks to

coastal development and population growth from sea-level rise and increases in

the severity and frequency of storms. It predicts with very high confidence

that Australia would suffer a significant loss of biodiversity in such

ecologically rich places as the Great Barrier Reef and the Queensland Wet

Tropics, as well as the Kakadu wetlands, south-west Australia, the

sub-Antarctic islands and alpine areas.

2.12 Notably in the light of the recent bushfires in Victoria, the IPCC

predicts with high confidence that risks to major infrastructure are likely

(66% to 99% probability) to increase, and that by 2030 the criteria for extreme

events that have been used for designing buildings and infrastructure are very

likely (90% to 99% probability) to be exceeded more frequently. There will be

greater risk of failure of floodplain protection, increased storm and fire

damage and more heatwaves.

2.13 The IPCC predicts with high confidence a decline in production from

agriculture and forestry by 2030 over much of southern and eastern Australia due to increased drought and fire.[7]

2.14 The Secretary of the Department of Climate Change warned:

Australia can expect higher temperatures, reduced rainfall in

the south and east of the country, rising sea levels and more frequent or

intense extremes, including drought, heatwaves, storm surge, extreme rainfall

and cyclones. Under a no-mitigation emissions scenario, average temperatures

across Australia are expected to rise by around five degrees Celsius by 2100.[8]

2.15 The effects of climate change also carry significant national security

implications:

...the cumulative impact of rising temperatures, sea levels and

more mega droughts on agriculture, fresh water and energy could threaten the

security of states in Australia’s neighbourhood by reducing their carrying

capacity below a minimum threshold, thereby undermining the legitimacy and

response capabilities of their governments and jeopardising the security of

their citizens. Where climate change coincides with other transnational

challenges to security, such as terrorism or pandemic diseases, or adds to

pre-existing ethnic and social tensions, then the impact will be magnified.[9]

Committee comment

2.16 The Committee heard from a broad cross section of stakeholders and the

vast majority agreed that policy needed to be adopted to address the challenges

of climate change.

2.17 The Committee believes that any policy that aims to deal with this

challenge should meet the following objectives:

-

Lower

Australia's emissions and contribute to a global solution.

-

Avoid

economic disadvantage or hardship whilst encouraging households to become more

energy efficient.

-

Transition

industry to a low carbon economy by providing assistance to avoid carbon

leakage, and ensure energy security.

-

Fast

track investment and research into renewable energy technologies.

2.18 The following chapters will examine the proposed CPRS legislation in

regards to achieving the above objectives.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page