Chapter 3 - Effects of private equity on capital markets

3.1

Regulatory bodies such as the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and the UK

Financial Services Authority discussed the possibility of private equity

reducing the quality and depth of capital markets.[1]

The RBA did however indicate in the Financial Stability Review that to date

this had not been the experience in Australia.

3.2

The committee's terms of reference ask it to assess the effects of

private equity on capital markets. The committee received limited evidence on

this matter. However, testimony from the regulatory agencies and other

witnesses suggests that there are limits to the growth of private equity that

will mitigate against significant equity market effects.

3.3

Capital markets also encompass debt markets. The evidence suggests that

activity in debt markets has a greater impact on private equity than the

converse. This chapter considers these capital market effects.

Equity markets

3.4

The same economic conditions that have expanded capital markets, and

mergers and acquisitions more generally, have driven the escalating numbers and

value of private equity transactions. These conditions include low interest

rates, high levels of liquidity and low volatility. Private equity provides

capital for companies to grow and consolidate; it is therefore in competition

with public capital markets to provide these funds. Consequently, some of the

concerns about the continuing growth of private equity relate to the

implications for the quality, depth and efficiency of public capital markets.

3.5

Some of the ways in which private equity can potentially affect

stockmarkets include removing companies from and relisting companies on stock

exchanges, as well as by indirectly affecting the quality of the markets

through precipitating defensive behaviour by listed companies that are seeking

to avoid a private equity buyout.

3.6

Hypothetically, these impacts may raise concerns about whether private

equity will reduce overall capital market efficiency, but in Australia the

relative size of the private equity industry, in combination with an

anticipated slowing of private equity activity, suggests that there will not be

significant effects on capital markets.

Stockmarket capitalisation

3.7

Theoretically, falling stockmarket capitalisation could lead to more

limited non-intermediated investment choices for investors, difficulties

raising capital, removal of larger companies from the market as private equity

deal sizes increase and increasing risk for investors due to fewer

opportunities to diversify portfolios.

3.8

Internationally, there is some evidence that changes to stockmarket

composition are occurring. For example, the value of stockmarket

capitalisation, after abstracting from changes in prices, is estimated to have

fallen in 2006 in continental Europe, the United Kingdom and the United States.[2]

However, it is difficult to attribute such effects solely to private equity

activity, despite the fact that private equity is more developed in those

markets than it is in Australia. While private equity does remove public

companies from stockmarkets, companies also delist for various other reasons.

Additionally, there are other explanations apart from delistings for falls in

stockmarket capitalisation.

3.9

In the United Kingdom, the funds raised by private equity in the first

half of 2006 exceeded new capital raised through initial public offerings

(IPOs) on the London Stock Exchange. There is also concern that in addition to

falls in market capitalisation, an increasing proportion of companies with

growth potential are being taken private. Consequently, the growth potential of

those companies that are listed may have been fully exploited and this could

then affect the quality of the stockmarket overall. Furthermore, the

development of a secondary private equity market, may lead to fewer private

companies going public.

3.10

Despite these developments, the UK Financial Services Authority

considers that while they could be meaningful in smaller markets, to date both

public and private markets appear to be deep, liquid and encompass high growth

potential companies.[3]

3.11

The evidence received by the committee suggests that private equity is

not a threat to the public capital markets in Australia.[4]

There are four main reasons. Firstly, despite the surge in private equity activity

in 2006, public company buyouts as a proportion of the overall equity market is

small — Australian leveraged buyouts (LBOs) in 2006 were equivalent to

approximately one per cent of the equity market.[5]

3.12

Secondly, the market is in the process of adjusting to changed

conditions, the effect of which is likely to be a slowing in the number and

value of LBOs. The Reserve Bank advised the committee that the global boom in

LBO activity has been a consequence of the low cost and ready availability of

debt. At the same time, returns on equity have been very high, and consequently

there has been a large financial incentive to replace equity with debt. The RBA

provided the committee with the following graph to illustrate this disparity in

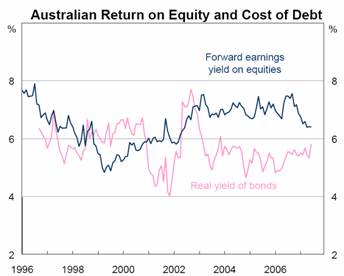

yields:[6]

3.13

However, the unusually large gap between returns on equity and debt is

starting to close. This is occurring because the cost of debt is rising

primarily as a consequence of the problems in the US mortgage market in recent

months. The spreads on corporate debt and lower rated debt have widened so it

is becoming more costly for investors to raise debt in the US (which is the

source of a significant proportion of LBO financing). Globally therefore, the

source of funding for these buyouts is starting to dry up and the conditions

that gave rise to the surge in private equity in 2006 have receded.[7]

3.14

At the same time, the earnings yield on equities is falling. Mr Ric Battellino,

Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank, suggested that this is because the

existing owners of listed companies are starting to ask a higher price in order

to be prepared to sell and this pushes down the yield:[8]

So the returns on equity and debt are coming back more into

line. Our feeling from that is that basically we have seen the surge in LBO

activity and it is unlikely to continue at the pace we saw last year. I think

the market has equilibrated.[9]

3.15

Additionally, there are other limits that will restrict how large a

proportion of the market private equity can become. For example, Mr David Jones,

Chairman, Australian Private Equity and Venture Capital Association Limited (AVCAL),

told the committee that private equity can only be relevant in certain

circumstances.[10]

He suggested that most businesses already attract adequate capital and

management attention, and it is only in a minority of situations where private

equity can act as a catalyst for change and propose a new direction for a

business to its owners that it will become involved in an organisation. This

limit on the size of the sector is borne out by the fact that it comprises only

around 20 per cent of mergers and acquisitions, approximately 1.4 per cent of

the enterprise value of the Australian Stock Exchange in 2006, under three per

cent of bank lending, and less than five per cent of superannuation fund investments.

Mr Jones advised the committee that these proportions are not markedly

different to those in the more developed private equity markets of the United

Kingdom and the United States.

3.16

Thirdly, private equity is not a perfect substitute for public equity[11]

and there remain many advantages for institutional investors to hold their core

equity investments in listed companies,[12]

thereby limiting the volume of funds that will be invested in private equity.

The key advantage is liquidity. Although institutional investors are often the

source of private equity funding, it would be too risky for them to lock away

large parts of their portfolio in private equity investments which can tie up

funds for up to five to ten years. Mr Battellino suggested that the requirement

for liquidity will act as a natural limit on the extent to which institutional

investors are prepared to put money into private equity.

3.17

Finally, one of the methods by which private equity firms exit their

investments and realise their gains is by listing shares on the stock exchange

in an initial public offering (IPO). Over the last five years, approximately 40

per cent of exits out of private equity took place through an IPO.[13]

The Investment and Financial Services Association Limited (IFSA) submission

suggests that 'it is possible to view private equity as a facilitator of public

listings rather than a raider of publicly listed companies posing a threat to

the exchange.'[14]

In its submission, AVCAL states that private equity complements and enhances

the operation of the ASX by building many businesses to a stage where they can

be listed.[15]

3.18

In conclusion, there does not appear to be any evidence to suggest that

the Australian stockmarket is being adversely affected by the growth in private

equity. Over the last four years, the market capitalisation of the ASX has

increased 130 per cent, from $0.6 trillion to $1.4 trillion. Over the same

period, the number of listed entities grew by 34 per cent to 2,029.

Furthermore, in the last financial year, it is estimated that private equity

raisings in Australia equated to only 10 per cent of the amount of new equity

raised in the same period.[16]

Defensive behaviour of listed

companies

3.19

One effect of private equity on capital markets may be in the defensive

behaviour of listed companies which try to make themselves less attractive to

private equity overtures. To do this, companies increase their gearing, buy

back shares, make a large purchase or otherwise draw down cash reserves.

Additionally, the increased LBO activity may encourage other companies to take

on additional debt in an effort to increase their own returns by replicating

aspects of the private equity model. While this behaviour may increase a

company's risk, the Reserve Bank's view is that in aggregate the effect on the

stockmarket is limited. However, the Bank considers this particular effect of

private equity activity to have greater significance than any impact on

stockmarket capitalisation.[17]

Debt markets

3.20

The evidence received by the committee suggests that activity in the

debt markets influences the level of activity in the private equity market

because private equity is heavily dependent on ready access to cheap credit.

This state of affairs is most clearly illustrated by the increasing returns now

being demanded by investors in debt instruments based on the US subprime

market, and the attendant spillover into debt markets more generally, which is

reportedly having an impact on private equity deals.[18]

3.21

The debt financing for private equity transactions is generally

initiated by banks (in Australia, the bulk of the financing comes from overseas

banks). The banks subsequently securitise or sell the debt into the market and ultimately

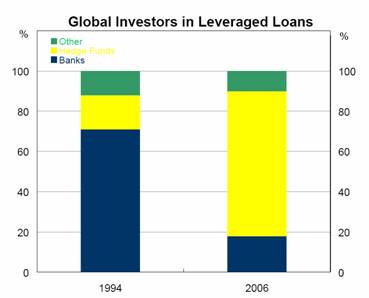

the exposure is held by hedge funds and a few other investors. The following graph

illustrates this trend by showing changes in the composition of the global

investors in leveraged loans over the past 12 years:[19]

3.22

The graph shows that over the period the bulk of the debt is now held by

hedge funds and the share held by banks is down to about 20 per cent of the

total. So, although the banks initiate the loans, hedge funds and a few other

investors are the main ongoing source of funding. While these practices have an

effect on debt markets, it is not possible to separate the impact attributable

to private equity activity from that attributable to financial market activity

more generally.

3.23

The debt is often structured into various tiers such as senior, junior

and subordinated debt which can be securitised and spread throughout the market

by being repackaged and sold, including to retail investors. The Australian

Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) is alert to the fact that retail

investors, while cognisant about the degree of risk attached to equity and

business investments, are often confused about the amount of risk that can be

inherent in fixed interest investments. These investments could include the

financial products that might flow into the market from private equity deals:

...there is some risk there, but consumers will misinterpret or

misprice the risk that is involved and merely take at face value that it is a

fixed interest investment and therefore you cannot lose your money and you are

going to be paid that level of interest.[20]

3.24

ASIC told the committee that it is vigilant about the quality of

disclosures in the prospectuses for selling these instruments to ensure that

they inform retail investors about the degree of risk that is associated with

the debt. The risk will be dependent on the complexity of the transaction,

where the debt ranks in the transaction and the level of security that is

attached to the particular debt offering.[21]

The Committee notes ASIC's related evidence to the Parliamentary Joint

Committee on Corporations and Financial Services where representatives emphasised

that its responsibilities in this area relate to ensuring adequate disclosure,

and that it does not make judgements in relation to the business that is being

carried on.[22]

3.25

Clearly, the existence of active secondary, and leveraged loan markets

for debt instruments is very important to enable private equity deals. Hypothetically,

if the banks could not remove their exposures from their balance sheets, they could

become more reluctant to lend for private equity transactions.

3.26

Recently there have been reports about private equity entities pulling

out of certain deals as a consequence of the reappraisal of risk in the US

subprime market.[23]

Additionally some corporate capital raisings have been postponed and there have

also been difficulties for banks in placing certain loans from large private

equity buy-outs in the capital markets.[24]

There are two aspects to these developments. Firstly, as credit spreads have

widened, the cost of debt — especially the more risky tranches — has increased as

investors demand a premium for more risky securities. This may mean that a

private equity deal potentially will not be as profitable as initially anticipated.

Secondly, issuers of securities may be finding some resistance in the market.

Nevertheless, the capital markets seem to be in the process of adjusting to

changed conditions and these most recent developments may not continue.

Predictions about this dynamic area are well beyond the scope of this report.

3.27

In summary, private equity transactions have an impact on debt markets

by increasing the supply of debt instruments. However, the attendant supply of

financial products is only a subset of the broader pool of instruments issued

in financial markets more generally. The greater impact is from debt markets which

have a more significant effect on private equity activity through the cost of

borrowing and the level of demand for the debt instruments that are created

from the deals.

Other effects

3.28

Private equity practices may enhance capital market efficiency in

different but related ways. These enhancements include widening the

availability and source of capital to companies, increasing the accuracy of

company valuations (for example, factoring in their growth potential),

enhancing the efficiency of corporate capital structures, and facilitating

corporate development and transformation.[25]

3.29

According to AVCAL, private equity has helped to develop the debt

markets in Australia by attracting more international banks to participate in

them.[26]

Its submission states that the entry of new lenders into the market has

increased the availability of funding for Australian businesses and investment

products for investors. In addition, private equity activity has helped to

build in Australia a liquid market in subordinated debt. These effects have increased

the efficiency of Australia’s capital markets.

3.30

Private equity, and mergers and acquisitions more generally, also

contribute to increased economic activity when they lead to the release of capital

that has been tied up in the companies that are taken over. A portion of the

released funds will be invested by the ex-shareholders.

3.31

IFSA also suggests that private equity imposes a competitive discipline

on public market operators, such as the ASX, to ensure that the cost of

compliance with market rules as well as listing and other fees are competitive.[27]

Conclusion

3.32

The committee concludes that although potentially private equity can

affect equity markets if it becomes large enough, there are certain

characteristics of the sector that should limit its size relative to the public

market. At the present time private equity is not having a significant effect

on the Australian stockmarket. Additionally, private equity transactions have

an impact on the debt markets but it may not be possible to disaggregate these

effects from other activity in the markets. Of greater significance is the role

that debt markets play in influencing private equity activity.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page