Chapter 1

1.1

Since 2001, there has been an exponential increase in private equity

investment in global markets from just under $US200 billion to just over $US800 billion.[1]

The strong growth in private equity in Australia is, however, a more recent

phenomena having accelerated only during 2006. Two proposed private takeovers of

high profile companies — Qantas and Coles — increased public interest in the

issue of private equity in Australia and its potential costs and benefits.

1.2

Accordingly, on 29 March 2007 the Senate referred an inquiry into

private equity investment and its effects on capital markets and the Australian

economy to the Standing Committee on Economics. The terms of reference for the

inquiry are as follows:

That

the Senate, noting that private equity may often include investment by funds

holding the superannuation savings or investment monies of millions of

Australians, and because of the actual and potential scale of private equity

market activity, refers the following matters to the Economics Committee for

inquiry and report by 20 June 2007:

- an assessment of domestic and international trends concerning private

equity and its effects on capital markets;

- an assessment of whether private equity could become a matter of concern

to the Australian economy if ownership, debt/equity and risk profiles of

Australian business are significantly altered;

- an assessment of long-term government revenue effects, arising from

consequences to income tax and capital gains tax, or from any other effects;

- an assessment of whether appropriate regulation or laws already apply to

private equity acquisitions when the national economic or strategic interest is

at stake and, if not, what those should be; and

- an assessment of the appropriate regulatory or legislative response

required to this market phenomenon, if any.

1.3

Given the high level of public interest in the topic, the Senate granted

a time extension and requested that the committee report on 20 August 2007.

Conduct of the inquiry

1.4

In accordance with usual practice, the committee first advertised

details of the inquiry in the Australian on 4 April 2007. Details of the inquiry were also placed on the committee's website. The committee wrote to a

number of organisations and stakeholder groups inviting written submissions and

ultimately received 31 submissions. These are listed in Appendix 1. The committee

also conducted three hearings: in Sydney on Wednesday 25 July 2007, in Melbourne on Thursday 26 July 2007, and in Canberra on 9 August 2007. The witnesses who appeared at the hearings are listed in Appendix 2.

Acknowledgments

1.5

The committee thanks all those who contributed to its inquiry by

preparing written submissions. Their work has been of considerable value to the

committee.

Background

1.6

This section provides some background to the private equity industry and

the nature of buyouts. It runs through the mechanics of private equity and the

types of transactions that are involved. It also refers to two private equity buyouts

of Australian businesses in order to illustrate the process. Finally, it

considers some of the benefits of private equity.

1.7

Chapter 2 will consider trends in the international and domestic private

equity market, as well as the forces that have driven the private equity surge.

Introduction[2]

1.8

Private equity provides a source of capital for enterprises in addition

to that available through the public capital markets. The private equity market

is highly diverse[3]

and every private equity organisation and individual deal contain their own

characteristics. The market encompasses everything from funding new company

start-ups (venture capital), helping companies grow and develop, through to

increasing the operating potential of mature companies, funding mergers and

acquisitions and turning failing companies around. It also covers large scale

takeovers of mature, listed companies. Private equity firms characterise their

funds as venture capital, expansion, buyout or distressed according to the life

stage of the companies in which they invest. Individual private equity firms

often target deal sizes within a particular range (which naturally correlates

to the life cycle stage of their target companies).

1.9

Private equity often invests in unlisted businesses. These can include

private family companies, other unlisted firms as well as public companies that

private equity firms purchase and delist from a stock exchange.

1.10

Private equity investments in venture capital and buyouts share some

common features but they involve different levels of investment and carry different

risks, incentives and potential gains for investors. Historically, venture

capital funds were such an important subset of private equity that the term

'venture capital' used to mean 'private equity'.[4]

However, today the market environment is quite different. Although the venture

capital segment of the private equity market remains essentially unchanged, the

top tier of the private equity market (and to a lesser extent the mid-market)

has evolved substantially. The increasing scale and complexity of the larger transactions,

some of which is filtering down into mid-market deals, is having a growing

impact and a greater profile.

1.11

Private equity buyouts of established firms are the principal focus of

the committee's inquiry. Unlike venture capital, these do not attract

government incentives to encourage investment.

1.12

Takeovers of mature companies are typically financed partly with debt

from third party lenders and increased gearing[5]

levels are a prominent feature of the private equity model. This feature particularly

distinguishes leveraged buyouts (LBOs).[6]

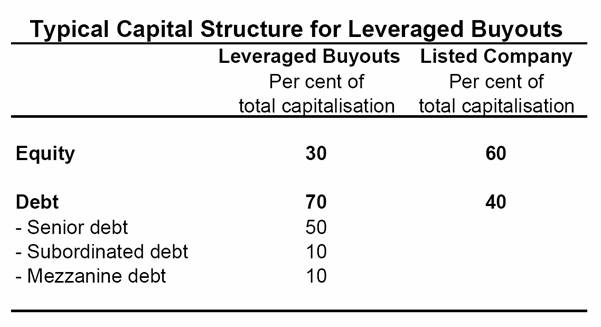

1.13

Typically when buying an investee company, LBOs use approximately 30 per

cent equity, supplemented by around 70–75 per cent debt for the acquisitions.[7]

In the larger and more complex deals, the debt component is usually structured

into various tranches, depending on its creditworthiness. The more senior debt,

which has a claim over assets, is typically about half the overall funding;

lower ranking debt such as subordinated debt and mezzanine debt makes up the

rest. The gearing ratio is typically over 200 per cent which is a higher level

of gearing than is typical for a listed company but it is not so high as to

trigger thin capitalisation concerns. This is shown in the following table:[8]

1.14

The investment by private equity is usually medium to longer term, an

average of 4.5 years, and unlike hedge fund investments, normally involves

taking control of the company concerned.

1.15

In the past, private equity targets included poorly managed companies

that provided the private equity firms with opportunities to turn them around

by introducing efficiencies through improved management and cost cutting. More

recently, mature companies with good cashflows that are undervalued by the

market have increasingly become the focus of private equity bids and the proposed

purchase of large, well-known companies (sometimes referred to as 'icons') has

raised the public awareness of the private equity industry.

1.16

Private equity pools the funds of investors and substantially augments

the funds with borrowings from financial institutions. Through leverage

therefore, it can accumulate significant amounts of capital. Investors in

private equity vehicles are wealthy individuals or institutions, including

insurance companies, university endowment funds, banks and superannuation/pension

funds. Institutional investors currently account for around 80 per cent of the

investor funds under management.[9]

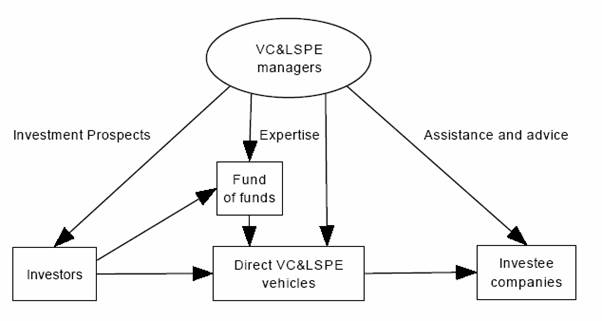

1.17

There are two broad types of private equity vehicles: those that

generally invest directly in investee companies, and those which pool funds and

generally invest through the direct investment vehicles.[10]

1.18

Direct investment is made by private equity firms in other firms

that are seeking expansion capital or have been identified as a buy-out target.

The controllers of the private equity firm decide which investments to make and

how the investment will be financed. Occasionally, several private equity firms

combine to form consortia for the particular purpose of acquiring larger

companies.

1.19

Indirect investment often represents the equity component in the direct

investment. It represents the capital contributed by those that invest in the

funds controlled by the private equity firm/s. These investors do not generally

control the underlying investment. Instead, they are typically seeking passive

exposure to private equity as an asset class.

1.20

Finally, there is at least a further layer of private equity investment

which is more passive than indirect investment. This involves investors,

institutional or retail, investing in a diversified fund of private equity

funds (fund of funds). That is, the fund places its investments with a variety

of other private equity funds which invest in unlisted companies. These

investors are seeking to minimise and spread the risk of investing indirectly

by relying on the skill and vetting of the manager of the fund of funds in

selecting the best possible private equity funds in which to invest. This type

of investment provides greater diversification of risk than investing in one

fund alone.

1.21

The investment decisions of the vehicles are made by a manager, who is

often a skilled business person and financial analyst. The manager spends

considerable time gathering commitments from investors, as well as evaluating

potential targets in which to invest. The manager further provides assistance

and advice to the investee company.

1.22

The usual relationship between the investors, managers, vehicles and

investee companies is illustrated below (reproduced from the Australian Bureau

of Statistics):[11]

The mechanics of private equity

1.23

Almost all private equity investment is conducted via investment funds

formed by private equity firms specifically for this type of investment.

Private equity fund structures can take various forms, but the most common is a

limited partnership structure. The limited partnership consists of a 'general'

partner who has unlimited liability for the debts and obligations of the

partnership and one or more 'limited' partners, whose liability is restricted

to the amount of their investment. The general partner is the private equity

fund manager and the limited partners are other investors in the fund. Limited

partners do not generally take part in the management of the business, though,

if they do so, they become liable for debts and obligations incurred during the

period of their involvement.

1.24

Investors undertake detailed evaluation of the fund manager, including

assessing and monitoring the manager's prior investment performance.[12]

The investors also review the fund documentation and have sufficient bargaining

power to negotiate terms with the managers. Additionally, they make use of

independent expert advisors who are expected to exercise high levels of

scrutiny and due diligence.

1.25

Typically, the funds have the following features:[13]

- they are mostly 'closed-end' structures. That is, all investments

of the funds will be realised and the money returned to investors within a

particular timeframe, usually 5 to 10 years. Investors pledge a certain amount

(committed capital) which represents the maximum amount that the fund may

drawdown. A drawdown from investors is the amount of capital committed by

investors that has actually transferred to a private equity fund in aggregate

for the life of the fund;

- the 'J-curve effect'. In most funds' early years, investors can

expect low or negative returns, due to the small amount of capital actually

invested at the outset combined with the customary establishment costs,

management fees and running expenses. As portfolio companies mature and exits

occur, the fund will begin to distribute proceeds;

- each fund has a specific investment mandate which details matters

such as the stage of the targeted investments, industries and countries that

can be invested in, and the proportion of fund assets that can be allocated to

any particular investment. As previously mentioned, private equity funds tend

to specialise in certain market segments. For example, some focus on purchasing

at a discount the debt of companies that are in, or close to, bankruptcy

(distressed debt). They then exert influence in the restructure and recovery of

the enterprise and are able to sell the debt at more favourable prices. Others

restrict their investments to management buyouts, or to particular stages of

venture capital (eg early stage, development, expansion etc);

- ‘blind pool’ investing. While private equity managers must follow

general investment guidelines and restrictions set out in the fund

documentation, they still have very wide discretion in selecting particular

companies in which to invest; and

- wide divergence of returns. The dispersion of returns between

upper quartile and lower quartile managers is significantly wider for private

equity managers than for listed equity managers.

1.26

After a fund is closed (ie after it has raised the funds to be managed)

the manager invests the fund's capital across a set of investments that fit the

fund's investment mandate or focus. The fund is said to be 'fully invested'

once this process is complete — typically after three to five years.

1.27

Over the life of a fund, the managers will assess hundreds of potential

investments, conduct detailed due diligence on perhaps 10 per cent of these,

but only invest in a small number. AVCAL suggests around 10 to 15 investments.

Competition for investments is fierce and a fund manager's bid will not always

succeed, in which case the time and money expended on assessing an investment

and preparing an offer is lost, although in some circumstances break fees may

be paid.

1.28

In order to illustrate how private equity operates, two examples of

private equity success stories are outlined below.

Pacific Brands

In November 2001, a private

equity consortium, including CVC Asia Pacific and Catalyst Investment Managers,

bought the Pacific Brands division of Pacific Dunlop for around $730 million.

This division held the biggest collection of consumer brands which included

Bonds, Grosby, Holeproof, Hang Ten, Candy and 32 other clothing, hosiery,

sporting and footwear brands. At the time, the deal was the second largest

Australian leveraged buyout (LBO) ever.

The deal was financed by

$235 million in equity provided by CVC and Catalyst, and around $500 million in

debt facilities.[14]

The new owners increased

spending on advertising – from an initial advertising budget of $30 million to

about $70 million; increased expenditure on staff training by 163 per cent,

strongly focused on working capital, and changed the outlook and strategy of

the company.[15]

For example, rather than making branded commodities as cheaply as it could and

delivering them to retailers to sell, Pacific Brands focused on building brands

that consumers would seek out. It shed $90 million of low-margin sales to

concentrate on its core brands.

The speed of decision-making

was increased under private equity. The initial board meeting to agree on a

strategy for the company reportedly took only 90 minutes.[16]

Within a fortnight of the buyout, the Chief Executive of Pacific Brands

received $20 million for capital expenditure.[17]

He says that approval for the funds took less than two hours and his request

was contained in a two-page summary outlining the purpose of the funds. This

was in contrast to his usual 60 pages to request funds for which he was still

waiting a year after submitting the request under the previous ownership

structure.

In April 2004 private equity

exited the investment. Pacific Brands was listed on the stock exchange at an

enterprise value of $1.7 billion and with a market capitalisation of $1.25

billion. The private equity investors made more than five times their initial

investment for an internal rate of return (IRR) of 105 per cent.[18]

Pacific Brands listed at a

share price of around $2.50.

Bradken

In December 2001, the Smorgon

Steel Group sold its heavy engineering division, Bradken, to a consortium of

CHAMP Private Equity, US-based ESCO Corporation and Bradken management.[19]

At the time of the $185.5 million management buyout (MBO) the company had a

turnover of $300 million and staff of 1400.[20]

The consortium funded the company with a total of about $200 million, 30 per

cent of which came from equity held by management and CHAMP, and 70 per cent

from bank borrowings.[21]

Bradken remained under private

ownership for just under three years. During this period, approximately $25

million of new capital expenditure was invested for capturing growth

opportunities and cost reductions. Bradken's EBITDA[22]

grew over 60 per cent from approximately $30 million per annum to $50

million per annum at the time of its successful[23]

public listing in August 2004. The

investment achieved an internal rate of return of 49 per cent[24] and CHAMP retained a 10.1 per cent

stake in the company.[25]

Bradken's Managing Director said

that the advantages of private equity ownership included the capital injection

into the company that the previous owners could not make.[26]

Other less obvious advantages included the reduction in non-value adding work

for senior managers. People became more focussed and there was a reduction in

reporting. 'You do not do as much filling out of monthly reports to send up

through the levels of an organisation; you are at the top of the organisation

and you talk directly to the people involved.'[27]

Mr Hodges also noted that as

Bradken became a stand-alone entity there was a period of three to five years

with specific things to do and targets to meet. He also found that the private

equity owner was significantly closer to the business and challenged many of

the known norms.[28]

There was also an effect on

employment levels. Prior to the private equity takeover a number of plants were

shut down and people retrenched. Although there was little capital expenditure,

efficiencies were driven through work practices and other changes. From 2002

onwards staff levels increased. Currently the company employs around 3,000

people and there have been no further staff reductions.[29]

Types of private equity

transactions[30]

1.29

There are several types of private equity transaction ranging from the

purchase of a private company, the purchase of a division of, or entire, public

company to the exit from the investment. These transactions are outlined below.

Purchase of a private company

1.30

The most common form of private equity transaction is the purchase of a

private company. Owners of private businesses increasingly see private equity

funds as an attractive source of expansion capital and management expertise

that is needed for the business to expand to a point where it will be suitable

and ready for a trade sale or initial public offering (IPO). In such cases, the

private equity manager invests capital for a stake in the business and also

provides ongoing advice to management of the company.

1.31

Many business owners who are looking to retire after building up a

business over many years, are selling to private equity managers in order to

realise the capital that they have accumulated in their business.

Purchase of

a publicly listed company

1.32

This is the smallest category of private equity transaction. According

to the Australian Private Equity and Venture Capital Association Limited (AVCAL),

only about a dozen publicly listed companies in Australia have ever been taken

private by private equity.[31]

Nonetheless, this is the category that receives the most attention,

particularly when icon status or economically significant companies are

involved.

Purchase of

a division of a publicly listed company

1.33

A more common type of private equity investment is the purchase by a

private equity fund of a division (rather than the whole) of a listed company.

Often the listed company describes the division being sold as 'non-core' and

has, for some years, concentrated its attentions (and capital investment) on

other divisions.

Sales of

businesses by private equity

1.34

Unless they are written off, all businesses bought by private equity are

sold, generally via either a trade sale or an initial public offering (IPO) on

the stock exchange or, in a small but growing percentage of cases, to another

private equity fund.

Returns

from private equity investment

1.35

The use of debt means that investors can receive a higher rate of return

on the capital they have invested in the funds. Private equity investment

targets a return of at least five per cent above the return on public

equity markets.

1.36

Fund managers receive a management fee based on the size of the fund and

they also receive a share in the capital gains delivered to the fund's

investors. The management fee is usually calculated as a percentage of the

funds under management. The percentage is negotiated between the investors and

the manager at the time the fund is raised. An indicative figure is one to two

per cent for larger private equity funds. This figure covers the overheads of

the business including salaries and the costs of conducting due diligence on

investments.[32]

1.37

The manager's share of capital gains (referred to as 'carried interest'

or 'the carry') is 20 per cent in virtually all funds globally and is

calculated after all fees and expenses paid by the fund have been returned to

the investors. The manager only receives a share in capital gains if the fund

has delivered a minimum return known as the 'preferred return'. If the target

is not met, the manager receives no share in capital gains. AVCAL advises that

the preferred return is usually similar to the long-term bond rate, currently

about eight per cent per annum.

1.38

These percentages for the returns from the investments are often

referred to as the '2 and 20 rule'.

1.39

There is a wide gap between the returns of the best performing private

equity funds and the rest. Private Equity Intelligence Ltd states that this gap

is around 10 per cent per year between the first quartile returns and the

median return of funds.[33]

Further, those funds in the bottom quartile return around 10 per cent below the

median returns per year. The differences in funds tend to persist over time and

this is a consistent pattern across all types of private equity fund, including

funds of funds.

1.40

Research conducted by Private Equity Intelligence Ltd indicates that the

largest funds outperformed the smaller ones.[34]

The difference between the groups in certain years is as much as 20 per cent.

It can be explained by the fact that the general partners who manage large

scale buyout funds are generally well known, established players with long and

successful track records, who have been able to raise increasingly large funds

as they become more experienced and have established good reputations within

the industry. Limited partners are keen to invest in these funds because of

their excellent returns, as well as their relatively lower risk compared to

other forms of private equity investment.

Benefits of private equity

1.41

Private equity generates economic activity through increasing mergers

and acquisitions. To make money they have to increase productivity and

profitability, which are important for economic growth. The industry argues

that it increases jobs and profitability which in turn generate taxation

revenue. Further, the deals generate significant fee income for banks, lawyers

and accountants.

For

takeover targets

1.42

In addition to an injection of capital into buyout targets, private

equity offers non-financial skills such as non-executive directors, extensive

business networks and management expertise. AVCAL claims that private equity

adds value to businesses by ensuring that each investment has the

characteristics outlined below.

Alignment

of interests

1.43

The foundation of private equity's ability to add value is its closer

alignment of interests between all shareholders, owners and management. In

contrast to the wide range of investors in public companies, each has a genuine

stake in the business and is firmly focused on increasing its value.[35]

Private equity-backed companies have concentrated and stable ownership and

private equity owners hold at least one board seat (and often control the

board) allowing for more effective engagement with management teams and the

board if problems arise. Further, the level of management ownership in private

companies is significantly higher than in public companies, which creates

additional incentives for the managers. In many cases, the senior executive

team (and sometimes those lower down) invest alongside their new owners, making

them owners too.[36]

The executives are expected to invest their own money into the venture — often

hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars.

Long-term

focus

1.44

Private equity invests with a three to five year horizon which enables private

equity-backed companies to invest in new products, new businesses and new

employees without concern for short-term earnings effects. This is in contrast

to public companies that may be under pressure from analysts and shareholders for

shorter-term returns. In addition to their continuous disclosure obligations,

public companies must issue annual and half-yearly reports, and in some cases

quarterly cashflow reports.[37]

These obligations can affect a company's day-to-day share price.

Detailed

due diligence

1.45

The research and assessment that private equity managers conduct during

the investment process provides detailed insight into:

- the strengths and weaknesses of a business, both financial and

non-financial;

- the dynamics of the industry in which the business operates;

- the business’s potential for growth; and

- the prerequisites for achieving this growth (for example, a

change of strategy, operational improvements and capital expenditure).

1.46

The insight from due diligence allows the private equity owners to

develop with the management a comprehensive and coherent long-term plan to

increase the value of the business. This plan will typically:

- stress the importance of sales growth as well as cost efficiency;

- emphasise cash as much as earnings;

- focus on a small number of essential performance measures;

- include a training and development program for employees; and

- include a capital expenditure program to ensure that the business

has the plant and equipment necessary to meet its growth targets.[38]

For investors

1.47

The key benefit of investing in private equity is the potential to earn

higher returns than in the traditional asset classes. In order to achieve these

returns, investors must accept a higher level of risk and also a less liquid

investment.[39]

According to UniSuper Limited, super-normal profits are expected to arise from

information arbitrage opportunities that result from the market's immaturity,

and hence relative inefficiency.[40]

However, the strong growth in the size of the private equity market and the

increase in the number of managers and investors in these markets may have led

to the information asymmetry arbitrage being eroded. As previously mentioned,

while some private equity funds yield significant returns, it is not

universally the case across the sector and in some cases investors are taking

on additional risk without receiving adequate compensation.

1.48

Another benefit for investors arises from diversification. Due to their

low correlation with traditional asset classes such as listed equity, property

and fixed income, private equity investments can be used to diversify an

investment portfolio and, therefore, to reduce the overall risk of the

portfolio.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page