Chapter 6 - Petrol Prices in Country Areas

Introduction

6.1

Inquiry after inquiry has found that consumers living outside of

metropolitan areas pay more for petrol, sometimes significantly so. During a

time of rising prices the differentials can be especially marked. Although it

is widely acknowledged that higher freight costs incurred in longer transportation

distances add to country petrol prices, this is not the only expense

contributing to higher prices in many regional, rural and remote locations.

6.2

As discussed in Chapter 3 – The Petrol Price Rollercoaster, the retail

price of petrol reflects the wholesale price plus a number of other factors,

including freightage and distribution costs, but the price is also influenced

by the relative absence of competitive pressures in many local markets, both at

the retail and wholesale level. Furthermore, a lower turnover rate of petrol at

retail sites often leads to higher prices at the bowser. These factors, as well

as a range of other influences which lead to country consumers[1]

paying more for petrol, are examined in this chapter.

Are country petrol prices really higher than city prices?

6.3

The Australian Automobile Association (AAA) described consumer sentiment

towards rising petrol prices, and in particular, the country and city price

differential:

...motorists find it difficult to understand why prices can vary

so much from place to place. This is particularly the case in rural and

regional areas, where prices are higher than in the capital cities...during the

past 18 months, there have been occasions when the differential has

increased dramatically in some locations.[2]

6.4

The Sustainable Transport Coalition WA submitted that whilst higher

petrol prices in country areas are justifiable to an extent, significant price

differentials are not:

It is obvious that those roadhouses which are isolated and have

to provide their own power generation and sustenance will have higher operating

costs than those in the towns, and this will be reflected in even higher retail

fuel prices at such roadhouses. However, some instances of petrol pricing in

(WA's) north west could bear scrutiny. It seems difficult to justify cases

where fuel is sold up to 32% higher per litre than Perth city prices.[3]

6.5

The higher cost of fuel in the country not only adds to the weekly costs

of transport borne by consumers, but residents also experience a general

increase in the cost of living and doing business when fuel prices are high.

Additionally, much of their travel is non‑discretionary, there are few if

any alternative transport modes, and the distances that people drive are often

greater than those of people living in metropolitan areas:

For Queensland’s Outback and remote business operators,

communities, and householders, fuel is an essential part of life. Fuel prices

impact on business and enterprise financial decisions and priorities, as well

as communities’ and householder’s quality of life and lifestyle.[4]

6.6

A number of personal submissions described the limited alternatives

available to country residents:

A lot of us do have to use our own car as there is no transport

in a lot of rural areas. [I] can't carpool as there is no one to carpool with.

I'm sure I'm not just speaking for myself here. How can people put up with it?[5]

It must be realised that we do not have services to our door

like urban dwellers, for example, even our garbage must be transported to 'collection

sites' for disposal. It is not economical to perform this task daily with one

bag of garbage, so it is collected until a trailer load can be transported,

likewise...water is essential...[and] must be transported from the public

bores...this demonstrate[s] that vehicles of a suitable power to weight ratio

must be utilised, [so] reducing petrol bills is extremely difficult.[6]

6.7

The Remote Area Planning and Development (RAPAD) Board reported that the

cost of living in a remote community like Boulia (located 1 719 km from

Brisbane, 305 km south of Mount Isa and 364 km west of Winton) was already

double the cost of living in a larger provincial centre like Toowoomba.[7]

6.8

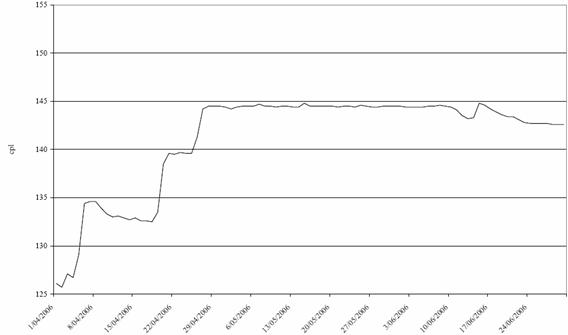

Figure 6.1 illustrates that the average price of petrol in metropolitan Sydney

as compared to NSW country is consistently lower for the period July 2005 to

June 2006 and the extent of the differential can vary quite significantly.

Figure 6.1––Average monthly

retail prices (Sydney and NSW country)[8]

6.9

Mr Jim Turnour noted that communities in Far North Queensland are

particularly dependent on the tourism industry and rising petrol prices have

reduced the number of domestic tourists travelling to Cairns, Douglas Shire, Cape

York and the Torres Strait:

Our communities are therefore experiencing hardships in a number

of ways as a result of spiralling petrol prices.[9]

6.10

The RAPAD Board commented that the latest statistics from Tourism Queensland

showed an eight per cent fall in tourism to Queensland's outback and that

anecdotally, higher fuel prices have been a major factor influencing the

decisions of potential holiday makers to the outback.[10]

The self-drive tourism market is especially threatened by rising petrol prices:

It is cheaper to fly to Bali from Melbourne return than to tow a

caravan from Melbourne to Winton and return as part of a holiday. A Melbourne

to Bali return airfare including prepaid airfare taxes, 7 nights'

accommodation, plus free full breakfast daily is currently being promoted at

$744. The indicative fuel cost of towing a caravan from Melbourne to Winton and

return is $1270.[11]

6.11

However, Caltex disputed the claim that a large price difference exists

between country and city petrol prices, stating that in the first half of 2006 there

was 'only a small difference on average between the average prices of petrol in

regional and metropolitan areas when freight is excluded, apart from WA',

accounting for an average difference of 2.2 cents per litre (cpl), not

including freight and excluding the WA market. This was argued to be similar to

the historical average.[12]

What factors contribute to the price of petrol in country areas?

6.12

The margins set by retailers are dependent on factors such as the average

volume of sales, the ability to retail goods and services other than petrol,

and the level of competition in the area. A retailer must have sufficient

margins to make a profit and keep the business viable. Country service stations

typically sell less than half the fuel of a metropolitan service station and

unlike metropolitan service stations, those in country areas tend to rely

primarily on their petrol sales to maintain the business, so they require

higher profit margins.

6.13

When questioned about the impact of the volume of sales on petrol

prices, Dr John Tilley from the Australian Institute

of Petroleum (AIP) told the Committee that there are many other factors which also

add to petrol prices in regional, rural and remote locations:

Senator JOYCE—In a local market then if I

were to go to Kalgoorlie where there is a massive amount of diesel used, I

would expect a cheaper price for diesel, wouldn’t I?

Dr Tilley—What you would expect in Kalgoorlie

is the underlying price level to reflect the wholesale price of diesel, plus

the local area factors and competition. How much does it cost to freight diesel

to Kalgoorlie? Is it double-handled along the way? Is it stored in depots so

the distribution and handling costs are higher? What is the nature of the

market in Kalgoorlie? How many service stations are located in that market?

What is the nature of competition between those service stations? What is the

average customer base for each of those sites? Do they have the opportunity to

move large volumes of diesel over time?[13]

6.14

The experience of operating a fuel retail outlet in a remote location

was described by Mr Michael Carr:

It does cost more to service the

country. I spent five years on the Nullarbor, running service stations there,

and we do hear a lot of complaints about the price of fuel in the country, but

there are a lot of extra costs such as freight, power and water.[14]

6.15

The key influences driving the country and metropolitan price

differential, such as freight, transport and distribution costs, local market

competition and the lack of price cycles in country markets, are canvassed

below.

Freight, transport and distribution

costs

6.16

The further away a fuel retailer is from a refinery terminal, freight

and transport charges will be higher, whilst the retailer may also have to pay

a distributor for fuel acquisitions, thereby creating an additional expense.

Caltex Australia estimated that freight is typically 1.5 to 3.0 cpl greater for

country deliveries as compared to deliveries in metropolitan locations. Whilst

freight and transport costs are perhaps the most widely publicised cause of

higher country petrol prices, as pointed out by Mr Turnour, the difference in

petrol prices cannot be explained by distance alone:

Cairns regularly experiences fuel prices greater than those in Innisfail

and Atherton. Both of these are smaller centres approximately 100 km from Cairns.

The arguments that service stations need to charge more because of higher

transport costs or smaller volume of sales do not hold up in these

circumstances. A lack of competition in the Cairns market is enabling service

station owners to price gouge local consumers.[15]

6.17

In terms of the WA petroleum market, the Royal Automobile Club of

Western Australia (RACWA) stated that whilst it is difficult to generalise

about costs, it is estimated that in many cases transport costs are only a

minor influence affecting the price of petrol.[16]

6.18

The costs of acquiring wholesale fuel from a source other than directly

from the refinery terminal, such as from a regionally-located storage depot or

from a distributor servicing the country area region, can also add further

expense to retail petrol prices. Where a retailer is able to source petrol

directly from a refinery terminal, then the wholesale price the retailer will

pay is generally lower. Purchases from a distributor (via a storage depot),

however, results in higher handling costs incurred by the fuel retailer and

additional expenses will be reflected in the retail price. BP submitted that

its direct retail activities in regional Australia are 'almost non-existent'

because the company sells petrol to distributors who then on-sell the BP

product to retailers.[17]

Competition in local markets

6.19

Caltex Australia summed up the key reason for the price differential as

competition:

In almost all cases, these differences are the result of local

competitive factors, including site volumes and site density, the presence of

discounters including supermarkets and the impact of new entrants seeking to

establish volume.[18]

6.20

The Committee found that while many people recognised that competition

in the local market has an impact on prices, concern remains as to why country

petrol prices do not fall at the same rate as those in metropolitan centres

following international price drops:

There is certainly a lack of competition and, in any particular

fuel retail outlet, volumes are much lower in these remote parts than they are

in the heavily populated parts of the country. So we recognise it is necessary

for the retailer to have a higher cents per litre mark-up on his product in

order to cover his overhead costs. But the bit that hurts is that price drops

at the retail level seem to be far quicker in the cities than they are out

here.[19]

6.21

Councillor Stanley Collins from the RAPAD Board described the impact of

reduced competition on country petrol prices:

I do not think that the claims have ever come from this region

that we are cross-subsidising or subsidising city consumers or that fuel

companies are jacking the price up out here to put a lower than cost price in

the cities. But they find it very easy because of the lack of competition just

to take an undue time to drop their prices here. Their margins are pretty good

out in these areas because of that.[20]

6.22

There is generally a time lag of around one to two weeks between changes

in these prices and price changes at petrol bowsers due to the averaging

formula used by refiners in Australia and the frequency of changes to terminal

gate prices. This lag is generally longer in country areas because petrol

stocks are replenished less often by wholesalers and retailers, due to the

generally lower volume of sales. This accounts for why a change to the

international price of petrol or crude oil tends to be reflected more rapidly

in metropolitan areas, as compared to that in country areas.

6.23

Locations which have a small population and perhaps little traffic

through the town are also likely to have fewer service stations and therefore

less competition, and higher margins may be needed to ensure the business is

financially viable and sustainable into the future. Fuel retailers located in

country areas that are close to or on major highways will tend to generate

higher volumes of sales of both petrol and other consumer goods, so these sites

may be in a position to offer a lower price for petrol. Alternatively, if they

are the only fuel retailer in the location or one of very few retailers, then

the retailer may be in a position to charge higher prices because of a lack of

local competition in the market.

6.24

Furthermore, greater competition in the wholesale market generally means

fuel retailers are able to secure supply at a lower price and so the relative absence

of competitive pressures not only in the retail market, but also in the

wholesale market in country areas means retailers have a reduced ability to offer

lower prices to consumers.

Lack of price cycles

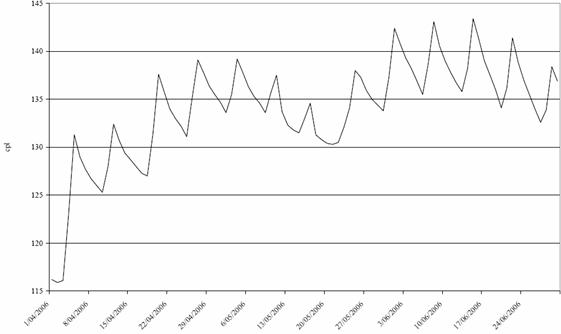

6.25

Reduced competitive pressures in the market of country locations

generally results in regular price cycles being uncommon and consequently, country

prices are more stable than in metropolitan areas. Whilst some country areas do

have regular cycles, these tend to be located in areas close to metropolitan

cities. Figure 6.2 illustrates the level of price movements in Tamworth, New

South Wales as an example of the extent of price movements in a regional hub.

Figure

6.2––Average daily retail prices for Tamworth (April–June 2006)[21]

6.26

This compares starkly with average daily retail prices over the same

period for Sydney, as shown in Figure 6.3.

Figure 6.3––Average daily

retail prices for Sydney (April–June 2006)[22]

6.27

Although a marked difference in petrol prices is apparent between cities

and country areas, the Committee received evidence that in some regional locations

the differential is declining. For example, the difference in prices between

Bunbury and Perth has declined. In January 2004, consumers paid on average

eight cpl more than in Perth, whilst in September 2006 the differential had

dropped to just under 5 cpl on average.

6.28

The entrance of a major new competitor to the Bunbury market appears to

have produced lower prices. Mr John Bain described the positive affect of increased

competition in this country market:

Coles Express has really put a cat amongst the pigeons. There

were two of them. Caltex and Woolworths on two sites were the only two that put

a cat amongst the pigeons. Now there are six.[23]

6.29

The differential between Busselton and Perth, and Kalgoorlie and Perth has

also declined. This phenomenon can also be observed in data provided to the Committee

from the RAPAD Board which compares average petrol prices in Brisbane and

Longreach between June 1998 and June 2006.[24]

This was supported in evidence submitted by the RACWA (included at Figure 6.4),

which illustrates the declining price differential between Bunbury and Perth.

Figure 6.4––Bunbury and Perth

price differential[25]

6.30

However, in other regional areas such as Albany and Geraldton the price differential

has remained steady whilst the differential between Port Hedland and Perth is

increasing:

The point we are making here is that it is difficult to

generalise about the trends in regional prices. There are local, geographical

and economic factors that tend to be pushing things one way or the other.[26]

Do petrol taxes impose a greater burden on country consumers?

6.31

As discussed in Chapter 5 – Petrol, Excise and GST, higher petrol prices

attract higher amounts of GST. Several submissions argued that GST on fuel in

regional, rural and remote communities should be abolished or lowered.[27]

The RAPAD Board submitted that outback residents are paying an additional 1 cpl

or more GST on their fuel purchases.[28]

Mr Turnour argued that this is discriminatory towards non-metropolitan

consumers:

It is completely unfair for communities in the Torres Strait to

be paying 7 cents per litre in GST more than those in places like Brisbane

and up to 15 cents more GST per litre in the outer islands.[29]

6.32

Mr Robert Parry proposed that the GST on fuel is removed in tandem with

an increase of 7 cpl to both fuel excise and the Fuel Tax Credits, and the

additional 7 cents collected in excise revenue could be distributed among

the State and Territory Governments at an agreed ratio.[30]

Mr Parry's submission also suggested a number of reforms to simplify the

collection of excise revenue.

6.33

Lower excise rates for fuel purchases in non-metropolitan areas were

also proposed:

The fuel excise system does not reward Outback and remote

business operators, communities and householders. It is discriminative,

increasing the cost of transported items through the compounding effect of the

fuel excise...

...The higher fuel price provides the opportunity for the

Australian Government to revert to the fuel excise system that existed prior to

1959. This would mean the removal of fuel excise as a means of raising general

revenue but hypothecated towards those areas from which it is collected –

expenditure on roads, rail, air transport.[31]

6.34

However, the Committee notes that those who are eligible for Fuel Tax

Credits would not benefit from such a measure because they are already

effectively paying reduced or nil excises on fuel. Mr Michael Potter from the

Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI) told the Committee that

reforms to the petrol taxation structure to assist country consumers would be

difficult to implement:

You could argue that fuel taxes should be lower in the regions.

That is probably too hard to implement, though. The Government had the Fuels

Sales Grant Scheme designed to keep down the price of fuel in rural and

regional areas, but most analysis showed that it was not hugely successful at

keeping down fuel prices in rural and regional areas.[32]

So what can be done to reduce country petrol prices?

6.35

Given that competition has been shown to make the most significant

contribution to lowering petrol prices in country areas, it is clear that consumers

derive benefit from a market which promotes healthy competition between

retailers and wholesalers and the emergence of more competitors into the

market. The example of Coles Express entering the Bunbury market in Western

Australia substantiates this point.

6.36

However, the Committee questions what can be done to help country

consumers, unless new competitors enter the market. The Committee agrees that

the most effective means of promoting competition in regional, rural and remote

areas is to ensure the market is free from unnecessary regulation or controls

which may restrict market growth.

6.37

In terms of intervening in the market, a submitter called for prices

surveillance by the ACCC to be reinstated in country areas to enable formal

petrol pricing investigations and to issue six monthly reports on price

movements.[33]

This view was shared by the NRMA which asserted that:

NRMA believes that the marked price differentials that exist

between regional and metropolitan areas (and which have increased substantially

in some locations) are sufficient justification for greater scrutiny by the

ACCC of petrol pricing in rural and regional areas. The ACCC should be given

sufficient powers to investigate the extent to which regional price differences

in automotive fuels reflect increased costs of distribution and marketing as

opposed to opportunistic price behaviour.[34]

6.38

The ACCC continues to monitor the city-country retail price differential

and retail prices in approximately 110 country towns. If the differential were to

widen significantly, it would increase the scope of monitoring. Matters

relating to the extent of desirable government intervention in the market are further

explored in Chapter 7 – Petrol Market Regulation.

6.39

As an alternative to Australia's reliance on petroleum products, the

RAPAD Board submitted that ethanol has the capacity to lower the bowser price

of fuel.[35]

However, at the hearing Councillor Collins told the Committee that he had mixed

feelings about subsidising ethanol production:

Not only I but everyone living in this part of Australia would

be very keen to see cheaper, alternative energy developed. But if it consumes

grain in particular it certainly impacts fairly heavily against the cattle

feedlotting industry, and much of the cattle coming out of this area go into

that industry. So while we might see cheaper energy we would probably also see

dearer grain prices, which would impact against us in the long term.[36]

6.40

For further information about alternative fuels, readers are referred to

the Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Committee report on Australia's

future oil supply and alternative transport fuels, tabled in December 2006.

6.41

Boyce Chartered Accountants argued that fuel subsidies would help out

rural communities struggling with rising petrol prices.[37]

It is the view of the Committee that perhaps the most targeted method of

alleviating the burden of rising petrol prices on country consumers is for

State and Territory Governments to review the level of subsidies they provide,

particularly given that all GST revenue collected on petrol is paid to the state

and territory governments. Currently, some jurisdictions provide subsidy

schemes to reduce petrol prices at either the wholesale or the retail level.

6.42

Victoria is the only state providing a subsidy at the wholesale level

(0.429 cpl) whilst jurisdiction-wide retail subsidies are provided in Queensland

(8.354 cpl), Tasmania (1.956 cpl) and the Northern Territory (1.10 cpl). In New

South Wales and South Australia, subsidies are restricted to particular zones;

five zones within New South Wales receive subsidies ranging from 1.67 cpl to

8.35 cpl; and in South Australia subsidies range from 0.82 cpl to 3.33 cpl

within two zones in the state. The Western Australian and the Australian

Capital Territory Governments do not provide subsidies.

6.43

This report has highlighted that whilst perhaps a source of frustration

for some, consumers in metropolitan areas reap the benefits of competitive market

activities which lower the price of petrol or at least provide consumers with

an opportunity to purchase petrol at a better price, such as on days when

petrol prices are at the lowest point of a price cycle. These are opportunities

simply not afforded to many in country areas, particularly those living in

remote locations or very small communities.

6.44

The Committee notes that the extent of subsidies offered in some

jurisdictions is very low or, as in the case of Western Australia and the Australian

Capital Territory, subsidies are not offered. To provide targeted assistance

to consumers in country areas, the Committee encourages State and Territory

Governments to review their existing subsidy schemes to make sure that the

people experiencing the greatest hurt because of rising petrol prices, are the

ones receiving the most assistance through subsidy schemes.

Conclusion

6.45

Petrol prices in rural, regional and remote areas are on average, higher

than prices in metropolitan areas. People in metropolitan areas benefit from

market forces and increased competition, whilst these just do not exist in

markets servicing people living in many regional, rural and remote communities of

Australia and to whom fuel is very much a non-discretionary commodity.

6.46

Although higher fuel prices flow through to higher costs of living in country

areas, other costs such as rent and property prices can be lower which goes

some way to offsetting them. Nevertheless, the Committee acknowledges that

sustained high petrol prices are particularly painful to those in country areas.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page