Chapter 3 - The Petrol Price Rollercoaster

Introduction

3.1

Daily and weekly fluctuations in the price of petrol cause significant bafflement

to many Australians, resulting in confusion about why price cycles fluctuate so

markedly. Consumers that provided submissions to the inquiry expressed great

frustration at the extent of the fluctuations in the price of petrol during the

course of the day or a week, describing fluctuations as great as 10 cents per

litre or more depending on the location. Consumers also voiced their concerns

at what they believe to be price hikes timed to coincide with public holidays

and long weekends.

3.2

The NRMA described consumer sentiment towards price variations as:

...a major source of anger for consumers, who express bewilderment

and feelings of being exploited when they see the retail price of petrol

varying from 10 to 15 cents per litre within the space of 24 hours and even

more over a seven day period.[1]

3.3

The frustration conveyed to the Committee by one consumer spoke for many

others in the community:

...I am frustrated and annoyed at the daily and weekly

fluctuations in the prices I pay for petrol in Sydney. For example, yesterday I

drove past the SOLO service station in Five Dock at 9.15am and the price of unleaded petrol was 129.9. When I next drove past at 4.30pm, it was 144.9 (a 10% increase). Two days earlier it had been 133.9. The simple task of filling

up each week has become a frustrating and stressful game of cat and mouse, most

days feeling ripped off and occasionally feeling like you got a bargain.[2]

3.4

The Motor Trades Association of Australia (MTAA) commented that price

volatility also creates challenges for fuel retailers and not just consumers:

While retail price fluctuations are a matter of irritation and

confusion to some motorists, they are also confusing and irritating for service

station operators (for the physical changing of prices on boards and pumps and

also because of the complaints from motorists that the fluctuations inevitably

and understandably generate).[3]

3.5

This chapter examines the nature of the price cycles that consumers

observe during the week, why they occur and the impact on the community. Finally,

the chapter considers whether the community derives benefit from the price

cycles or if action should be taken to reduce fluctuations in the price of

petrol.

What is the cause of petrol price cycles?

3.6

Petrol price cycles vary in intensity and duration according to the

location and the number of competing fuel retailers in the area. Aggressive

price cycles tend to be observed most commonly where a number of fuel retailers

are competing for market share, such as along main arterial roads where

fluctuations in the price of petrol can be observed throughout the day.

3.7

Volatile price cycles are apparent in major metropolitan cities and the

surrounding areas, as well as in some rural centres. They tend to be regular

and frequent, displaying a saw tooth pattern which suggests that prices rise

and fall over a short period. This is presented in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1––Retail unleaded price cycles in metropolitan areas

(March 2006)[4]

3.8

Evidence to the inquiry noted the greatest variations to the price of

petrol on the retail market are observed between early in the week (when daily

average prices are generally at their lowest point) to late in the week when

prices reach a high. According to analysis conducted by the ACCC, of the five

largest metropolitan centres price cycles commonly tend to peak in Sydney, Melbourne,

Brisbane and Adelaide on Thursday and reach the lowest daily average on

Tuesday. In Perth prices tend to peak on Wednesday and reach the lowest point

on Sunday.[5]

The ACCC commented that regular price cycles tend not to exist in Canberra or Darwin.

3.9

This pattern of activity is attributed to a number of key factors

including:

- competition between petroleum retailers for market share,

including the provision of price support to some retailers by the oil companies

to greater facilitate competition;

- variations in the demand for petroleum products during the week

which influences retail petrol prices;

- variations in the wholesale price paid for petrol (for example, a

cheaper price paid for the wholesale purchase of petrol means that retailer can

engage in more aggressive competition);

- consumer behaviour whereby consumers actively seek out the

cheapest price for petrol, thereby driving strong competition between retail

fuel outlets for market share; and

- a stable and consistent demand for petroleum products that

facilitates regular and predictable price cycles by petrol retailers.

3.10

Whilst it is clear from the discussion in Chapter 2 that the price of

petrol is constrained by circumstances in the international petroleum market

and tightening Australian fuel standards, competition in the market is the

foremost driver of petrol prices in the retail market. The extent to which the

retailer can engage in aggressive market competition to lower prices and

capture a greater share of the market depends upon the ability of the retailer to

secure low prices from petroleum wholesalers or distributors.

3.11

The difference between the retail price of petrol (the price paid by

consumers at the pump) and the wholesale price of the fuel (the price paid by

the retailer to purchase petrol from a refinery or distributor, such as the

Terminal Gate Price) is referred to as the retailer's margin. Figure 3.2

outlines what is included in the price of petrol at the pump. It can be noted

that margins (the oil company, distributor and retail fuel operator share) are

only a very small percentage of the total price of petrol:

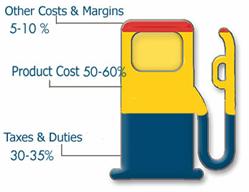

Figure

3.2––What is included in the price of petrol?[6]

3.12

For example, the retail price of petrol of 134.1 cents per litre (cpl)

could be broken down into the following components:[7]

- product: 79.5 cpl

- tax (excise and GST): 50.3 cpl

- retailer's and refiner's margins: 4.3 cpl

3.13

The retailer's margin also incorporates any additional costs to the

retailer incurred during the process of obtaining fuel from a wholesaler or

distributor such as freight and distribution costs whilst the price may also be

affected by factors in the wholesale market which could lead to more

competitive prices being secured by the retailer.

3.14

The cost of freighting the petrol from the terminal gate of the refinery

to the retail fuel outlet generally increases the further away the retailer is

located from the petroleum terminal or refinery. For retailers located at

significant distances from a terminal, the retailer may rely on a distributor

sourcing petrol from a storage depot in a regional area, thereby producing higher

costs for the supply of petrol as compared to retailers which are able to

source petrol directly from the terminal gate. These factors can add to the

price of fuel at the pump and create considerable price differentials depending

on the location of the retailer.

3.15

Business arrangements between the wholesale supplier and the retailer

can be influenced by the circumstances in the wholesale market. For example, where

several wholesale suppliers are present, competition between wholesalers often

results in the retailer securing supply at lower prices.[8]

Contractual terms and arrangements (including any discounts for bulk purchases

or price support provided by the major oil companies to the retailer) between

the wholesaler and the retailer can also enhance the ability of the retailer to

compete more aggressively with competitors in the retail market. This is

because the retailer may have paid a lower wholesale price for the petrol (so

they can engage more vigorously in price wars with other retailers) or has an

arrangement established with an oil company that will see any losses sustained during

competitive price wars being subsidised by the oil company.

3.16

Alternatively, the retailer may have structured their business in such

as way as to be able to subsidise any losses in the sale of petrol through

increased sales of other goods in the business (that attract higher profit

margins than petrol) such as food or beverage sales. Caltex Australia described

the importance of maintaining traffic through fuel retail outlets, commenting:

If somebody finds that the traffic through their station is low,

they will follow the price down of somebody who has already led the price down

to get their volume back up. This is very much a low-margin, high-volume kind

of business, and it is important that people bring more motorists into their

stations. From the standpoint of the person who operates the station—in many

cases, franchisees—the majority of their profit actually comes from what they

sell in their convenience store and not what they sell at the petrol pump. So

bringing the traffic in is very important to maintain overall profitability.[9]

3.17

A detailed discussion on the impact of competition and whether

circumstances exist within the Australian petroleum market that could indicate anti-competitive

behaviour is included in Chapter 4 – Competition or Collusion? Furthermore, a

very comprehensive discussion of the causes of the price cycles is included in

the ACCC report, Reducing Fuel Price Variability.[10]

Why is the public so acutely aware of petrol price cycles?

3.18

Price cycles affect the community in different ways. Petrol consumers

can generally be considered as people who are either:

- acutely aware of the price of petrol and that take direct action

to benefit from reduced petrol prices, such as driving across town to purchase

petrol from a lower cost supplier and only buying petrol on certain days of the

week;

- aware of prices but that will limit modifying their behaviours to

take advantage from cheaper petrol prices, such as preferring to buy petrol

early in the week where possible; and

- largely unaware of petrol prices and do not modify their

behaviour in accordance with the price of petrol.[11]

3.19

The Royal Automobile Club of Queensland (RACQ) explained that some

cross-sections of the community are far more sensitive to variations in the

price cycle than others:

Obviously, there will be those in lower income groups who will

probably be more sensitive to movements in petrol price than those at a higher

income level. Those people in lower income groups are more likely, in the short

term, to cut back their consumption and cut back discretionary driving and so

on than those at a higher income level.[12]

3.20

Commentators noted that the price of petrol is highly visible to the

public, with price boards at the front of retail fuel outlets providing

consumers with the ability to remain cognisant of price fluctuations and to

identify which retailer is offering the lowest price at a particular time. The

ACCC noted that because of these factors, petrol prices are more visible to the

public than are the prices of other household commodities.[13]

3.21

Unleaded petrol (ULP) is also a largely homogenous commodity.

Invariably, the price boards at the front of retail fuel outlets will advertise

the price of regular ULP. Although consumers may have a preference for a

certain brand of petrol, the homogenous nature of the product clearly gives the

price-conscious consumer the ability to select a retail fuel outlet based on

the most competitive price. Therefore, retail fuel operators rely on

competitive prices as the key to remaining viable in the industry.

3.22

Whilst price cycles also apply to other consumer goods, such as

groceries and household consumables, the cycles generally change on a weekly

basis rather than a daily basis. Prices also tend not to be displayed nearly as

prominently as is the price of petrol, which can be readily identified on large

price boards. There is also generally a greater public awareness of petrol

prices than perhaps applies to other consumer goods. Mr Mick McMahon of Coles

Express commented:

When I am at a barbecue or with friends and I say what I do, the

first question is going to be something about the price of fuel...and everybody

knows the price of fuel to the second decimal point. But if I say, ‘Tell me

about the price of milk,’ in general almost no-one knows it...or the price of

bread.[14]

3.23

Furthermore, Mr McMahon said that public sensitivity towards petrol

prices and cycles is certainly understandable:

...it is such a big part of people’s weekly budget, particularly

when prices are very high. So I would say that in Australia people drive large

distances. We put a price board on just about every corner but certainly on

every location, with big letters telling people what the price is, which is not

necessarily the case in all markets overseas. There is heightened media

interest—I do not know why, but there certainly is. So the prices are known.

There are Pricewatch segments. It is on talkback radio.[15]

3.24

Evidence also discussed the role of the media in creating hype around petrol

price cycles, particularly around long weekends and public holidays:

I would put it down to the media in many respects. The media

have a whole series of stories that are repeated time and time again, and

petrol prices and holiday weekends are one of those stories which you can be

sure will occur regularly. We have experienced this. We get ready for it, and

we put information out—such as the sorts of things that we are discussing with

you today—but, frankly, the industry is a whipping boy when it comes to this sort

of thing.[16]

3.25

The Royal Automobile Club of Queensland (RACQ) told the Committee that

media reporting on price cycles actually helps to minimise enquiries from the

public:

We do hear a lot from our members but, at the times when petrol

prices spike, we receive an extraordinary number of queries and requests for

comment from the press. Often those requests for comment can outnumber the

actual requests we hear from members on a particular day when the price has

risen. I think that we would receive a lot more inquiries and comments from our

members if indeed we were not commenting on a regular basis via the media—TV,

radio, newspapers and so on.[17]

3.26

The Western Australian Commissioner for Fair Trading argued that regular

media attention contributes to encouraging retailers to offer cheaper prices

for petrol because it raises the profile of retailers selling petrol at a

better price than their competitors.[18]

Is it true that petrol prices rise on long weekends and public holidays?

3.27

A number of submitters contended that prices tend to hit greatest

heights at the onset of a long weekend, coinciding with events such as Easter,

Christmas or other holidays where people are most likely to be travelling long

distances in the car.[19]

3.28

Describing the Perth petrol market, a consumer commented that:

...it is particularly remarkable how [world oil prices and

associated factors] always seem to come into play and cause sharp increases in

petrol prices just before long weekends and public holiday periods in WA.[20]

3.29

Mr Gerald Hueston, President of BP Australia responded to claims that

prices increase before long weekends, stating:

Mr Hueston—Moving on to retail pricing: one

of the issues that get highlighted in the media is that whenever there is a

long weekend the prices tend to go up. Our argument would be that, in normal

price cycles in most of the metropolitan cities, the prices tend to go up later

in the week and then diminish over the weekend and the early part of the week,

and then they spike back up again. So, if you have a look at that—

CHAIR—It is not just long weekends, though.

Mr Hueston—It is every weekend. The objective of showing

this is: could you pick where the long weekends are? Our view is that you could

not, when you look at that detail. There is nothing special about the long

weekends compared with any other week in which we operate.[21]

3.30

Mr Michael Carr, an independent retail fuel owner, stated that

increasing the price of petrol prior to a long weekend would have only a

limited effect on profit margins for oil companies:

...more fuel is sold to industry than to the general public

regardless of long weekends or not. If the fuel cycle timing was designed to

take advantage of extra volume then it would always cycle up at the start of

the working week.[22]

3.31

Mr Richard Beattie from Caltex Australia commented that such media

attention would be better directed to raising awareness about price cycles:

So I suggest that it is this constant opportunity the week

before a holiday weekend for various people—and not just the media. There are

certain motoring organisations whose representatives say, ‘Look what’s coming,’

but they could just as easily make the comments that we have been making about

price cycles. We are more than prepared to say to consumers, ‘Take advantage of

the [price] cycle.’[23]

3.32

Analysis by the ACCC of the five major metropolitan markets (Adelaide, Brisbane,

Melbourne, Perth and Sydney) also did not support the hypothesis that the

price of petrol is higher before public holidays when compared to non-public

holidays, commenting:

There have been suggestions in the media that petrol price

increases before public holidays are always higher than the price increases

that occur at non-public holiday times. From [ACCC] analysis this generally is not

the case for the five largest metropolitan cities.[24]

3.33

Examining petrol price data from the 2006 Queen's Birthday long weekend

(9–12 June), Figure 3.3 demonstrates that the national average petrol price did

not deviate significantly from the typical price pattern for this holiday:

Figure 3.3––Retail ULP price

cycle for Queen's Birthday long weekend 2006[25]

Does the public benefit from price cycles?

3.34

The question arises as to whether the public is deriving advantage from

price cycles, or are they just an unnecessary source of frustration for

motorists?

3.35

BP Australia and Caltex asserted that points in the cycle of petrol

where the prices are lower coincide with the days when the greatest volume of

petrol is sold, reflecting that consumers understand the price cycles and seek

to benefit from cheaper prices.[26]

Based on data from the Sydney and Melbourne markets, the ACCC report on petrol

price variability found that around 60 per cent of the total volume of fuel is

sold at prices which are below the average price of petrol for the cycle (such

that consumers are buying on the days where petrol is at its lowest price),

whilst the remaining 40 per cent of volume is sold above the average price for

the cycle.[27]

3.36

The ACCC report into reducing fuel price variability[28]

recommended undertaking a public campaign to raise consumer awareness of the

price cycles so that more people may benefit from lower prices. Consequently,

the ACCC launched its petrol price website in November 2002 to provide

consumers with information on taking advantage of the petrol price cycles in

the five major metropolitan centres.

3.37

However, the MTAA commented that because price cycles are not observed

across all areas of Australia, not all consumers are able to benefit from price

cycles:

It is therefore motorists in particular locations, rather than

all motorists, who benefit from price fluctuations in the retail price of

petroleum.[29]

3.38

Furthermore, price cycles are of little use to

some consumers such as industries that are reliant upon the use of

vehicles to sustain their businesses and cannot limit purchasing to certain days

of the week:

Contractors are at the mercy of the weekly cycle of retail

petrol prices. Contractors are usually in no position to take advantage of

lower price days because of the sheer quantity of petrol that their vehicles

consume while performing the mail service.[30]

3.39

The Australian Taxi Industry Association noted:

The trend to volatile pricing in capital cities, especially

where it is based on particular days of the week, is especially frustrating and

nonsensical from the perspective of an industry such as ours that purchases

fuel on a daily basis. The taxi industry has little capacity to avoid

purchasing fuel on high price days.[31]

3.40

One consumer called for the mandatory introduction of a recommended

retail price to be displayed by retail fuel operators to counter fluctuating petrol

prices:

It may be a perception by the general public, but it is a very

strong perception, that the oil companies hold the public to ransom, and no-one

inclusive of the government are capable of controlling them. I would also

suggest that the continuing changing of the displayed price at service stations

is just another ploy by the oil companies to keep the general public in a

complete state of confusion.[32]

Intervening in the market––the Western Australian experience

3.41

Intervention in the Western Australian petroleum market has reportedly

led to a reduction in the volatility of price cycles, at least on a daily

basis. The Western Australian Government introduced the FuelWatch system in

January 2001, a petrol price monitoring system to increase price transparency

and pricing certainty in the WA petrol market. The system is administered under

the state-based Petroleum Products Pricing Act 1983 (the Act) and the

associated regulations and orders and applies to fuel retail outlets within the

FuelWatch boundaries.[33]

3.42

Under the Act retail fuel outlets must notify the WA Commissioner for

Fair Trading about the next day's petrol price for ULP, premium unleaded petrol,

lead replacement petrol, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), 98 RON and biodiesel

blends by 2 pm on a daily basis. Subsequently the prices are publicly announced

on both the FuelWatch website and via a telephone hotline after 2.30 pm. The retailer is committed to selling petrol at the notified prices for the

following day. Retailers within the FuelWatch boundaries must also ensure they

maintain price boards displaying the retail price of ULP, LPG and three other

fuel products.

3.43

On 19 December 2002, additional measures were introduced in WA to

increase price transparency in the wholesale petroleum market and to facilitate

access to more competitive wholesale prices from terminals. The Terminal Gate

Price (TGP) system requires that terminal operators advise the Commissioner for

Fair Trading whenever the TGP is changed, as well as the components making up

this price. Prices (not including individual components) are published on the

FuelWatch website so retailers or distributors are able to compare wholesale

petrol prices. For all purchases wholesalers must provide itemised invoices

which clearly list the TGP plus any other charges included in the price such as

freightage or branding. TGP information is also used by the Commissioner for

Fair Trading to monitor movements against fluctuations in the international

petrol pricing benchmark and average retail petrol prices for the major oil

companies in Perth with terminal gate prices.[34]

3.44

The benefits of the FuelWatch system to date were described by the Commissioner

for Fair Trading, Mr Patrick Walker as:

...enabling consumers to plan their purchases and to buy at the cheapest

price in their area. With information about the cheapest price being made

available through FuelWatch and the media, retailers are encouraged to offer

lower prices in order to gain sales.[35]

FuelWatch has proven to be an extremely popular and useful

source of fuel pricing information. Continued growth in the number of motorists

using the various FuelWatch services suggests that WA consumers are planning

their fuel purchases to benefit from the competitive rates being offered on any

given day.[36]

3.45

He told the Committee that metropolitan motorists reported 'saving an

average of $2 per week' through FuelWatch information, equating to a

substantial saving for motorists annually, whilst petrol prices in Perth were

now lower than those in Adelaide and Brisbane for a year and lower than prices

in Sydney and Melbourne 'for the majority of the year'.[37]

Furthermore:

Price hikes now occur much less frequently in WA than previously

so consumers are able to benefit from lower prices for longer periods. Perth

now has significantly longer price cycles than other Australian capital cities.

On average ULP price hikes are occurring every 13 days in Perth compared to

every seven to eight days in the eastern states capitals...[38]

3.46

The ACCC cautioned that whilst the FuelWatch system increases

transparency in petrol pricing, the 24-hour notification rule may have a

negative impact on competition in the market:

There was—this is anecdotal, of course—an individual retailer in

WA that just a little while ago objected to the 24-hour notification and, as I

recall, posted on the site that he intended to charge $100,000 a litre the next

day for petrol because he frankly was going to work on the basis of discounting

over a more regular period than 24-hour notification. The sorts of movements

that we were talking about earlier today in discounting have tended,

particularly where there is vigorous discounting in the price cycle occurring,

to occur on a half-hourly or hourly basis. Of course, that cannot occur in Western

Australia, where 24-hour notification is required before the price can be

posted. To that extent, we have concern that that 24-hour notification can have

a negative impact on competition.[39]

3.47

The proposition that the 24-hour notification rule be rolled out

nationwide was met with criticism by Queensland-based independent fuel

retailer, Matilda:

I find that quite scary. I have looked at that. If you went to

work in the morning and found that the service station down on the next corner

was a cent or two below you and you did not have the ability to come down and

match that, I think that is wrong. I think I would be prepared to go to jail. I

would just say, ‘I’m going to drop my price and if you want to prosecute me for

it, go ahead.’[40]

3.48

The value of FuelWatch in lowering petrol prices was questioned by Mr Gerald

Hueston, President of BP Australia:

I think what FuelWatch does is slow down the speed with which

the cycle moves—both on the way down and on the way up, I would suggest. It is

very difficult to untangle what is happening in a competitive sense and what is

being driven by regulation. Frankly, I think it is a long bow to draw that

regulation has driven lower prices.[41]

3.49

In addressing concerns about the 24-hour notification rule, the Royal

Automobile Club of Western Australia's (RACWA), Mr David Moir stated that in

addition to providing information to consumers about where they can secure the

lowest petrol prices, the 24-hour rule provides consumers with confidence that

the advertised price will not change over the course of the day. He also described

FuelWatch as reducing the severity of price cycle fluctuations in the market:

Senator WEBBER—When we first heard from the ACCC, I asked

them about our FuelWatch system. They said they thought that one of the

disadvantages would be that we do not get the wild fluctuations downwards in

price, but it seems to me, looking at your graph, that it protects us from some

of the wild fluctuations upwards. We are probably winning more than we are losing,

if you look at that graph.

Mr Moir—Yes. At any point in time, in all

of the capital cities there is a wide fluctuation in prices. It depends on

whether consumers choose to shop around and buy in the bottom half of the price

market or whether they are just price takers. But yes, there are some wider

fluctuations in Sydney, for example...[42]

3.50

When asked to substantiate the claim that the FuelWatch system is the

variable responsible for lowering petrol prices in the market, Western

Australian Commissioner for Fair Trading, Mr Walker was unable to provide clear

evidence:

CHAIR—I dare say that you have already covered this in an

indirect way in your submission and that your report deals with it, but let me

ask you straight out: why do you say that there is a causal relationship

between the lower average price of fuel in Western Australia and the 24-hour

rule?

Mr Walker—Because I can find no

other explanation.[43]

3.51

The uncertainty of FuelWatch as the variable producing lower prices was emphasised

by the most recent major competitor to enter the WA market, Coles Express:

First of all, you have probably heard through your hearings that

when Coles Express entered various markets, we caused quite a shake-up in the

marketplace. Without seeing the data that you are referring to, I think there

was quite an impact to start with when Coles Express entered [the Western

Australian] marketplace. It was a marketplace that has at least one very strong

independent and a number of others. It caused quite a bunfight as we competed for

customers. I would struggle to differentiate what is the effect of that

happening, the particular dynamics of that marketplace, versus the effects of

FuelWatch. I think all FuelWatch has done is flatten the price cycle. It may be

superficially attractive to regulators and so on, but I think customers lose.[44]

3.52

Whilst the FuelWatch system may have asserted a positive influence on prices

in the WA petrol market, the Committee notes the ACCC's concern that the 24-hour

notification rule may reduce the competition in the market, and competition has

been shown to lead to consumers getting a better deal. Further investigations

into the variables driving petrol prices in the WA market may produce more

conclusive evidence directly attributing the FuelWatch system to benefits for

consumers. The Committee is unpersuaded of the benefits of the WA system, and

sceptical of the (in some instances) self-serving claims about its effects in

reducing prices. The Committee is concerned that, in a market characterised by

an extremely high degree of price volatility––both upward and downward––the

imposition of an artificial constraint upon that volatility would be

counter-productive, and is just as likely to operate to arrest falls as well as

rises in the petrol price.

3.53

The Committee notes that the ACCC, which is in the best position of all

of the witnesses to bring an independent and fully-informed expert view to the

consideration of this issue, shares its scepticism of the WA system's claimed

benefits.

Conclusion

3.54

Regulating petrol prices in Australia could lead to a more stable market

with fewer fluctuations in the price of petrol at the pump and perhaps this

would address consumer concern about price cycles. However, such intervention would

interfere with competition in the market and possibly reduce the extent of

market fluctuations, both at the higher and the lower ends of the

market. This would be bad for consumers who currently benefit from purchasing

petrol at the lowest points in the price cycle.

3.55

The ACCC reported that 60 per cent of petrol is purchased at the lower

price points in the cycle and so it stands to reason that petroleum retailers

and oil companies compensate for losses sustained by selling the remaining 40

per cent of petrol during higher points in the price cycle. Capping the price

of petrol would potentially result in a situation where the price of petrol is

unlikely to be as competitively priced at the low points in the cycle because

the petroleum industry would have a limited capacity to recoup such losses through

selling petrol at a higher price at other points in the cycle.

3.56

Whilst regulating the price of petrol would certainly lead to a

flattening of the band in which the petrol prices fluctuates, this would most

likely result in an overall increase in the price that consumers pay for petrol.

And as argued by the ACCC, attempts to remove the price cycles would be to the

detriment of consumers.[45]

By understanding petrol price cycles, lower prices can be attained to the

benefit of Australians and the Committee encourages greater promotion of the

cycles by not only the ACCC, but also by motoring bodies within Australia which

are in direct contact with the people who will benefit most from such

information.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page