Appendix 5 - Factors contributing to household debt

The evidence presented to

the Committee focussed on housing related debt and credit card debt. Although

opinions differ about impact of the various contributing factors, most

commentators agree that the primary factors behind the strong growth in

household debt levels include:

-

Freeing up of the financial markets, which meant

credit became much more readily available;

-

A prolonged period of low inflation and low

interest rates gave consumers a feeling of confidence in the economy;

-

Increased competition in lending, more

advertising and promotion;

-

A much wider range of products from lenders,

including lines of credit and interest-only loans;

-

The stockmarket boom in the mid-to-late 1990's

followed by the real estate boom and the ability of consumers to borrow for

investment purposes;

-

The growing acceptance of the concept of debt

used for investment as 'good debt', actively promoted by financial advisers

promoting wealth creation strategies based on investment in equities and

property;

-

Increasing financial literacy and the

realisation of the baby boomer generation that it would have to take more

responsibility for funding a comfortable retirement;

-

Rising asset values, especially in residential

real estate, which gave home owners a feeling of increased wealth (so-called

'wealth effect'), and the ability to unlock that wealth through new financial

products such as loans based on home equity;

-

A sustained period of economic growth, low

inflation, low interest rates, and falling unemployment.

Treasury sees the rise in

household debt as:

...a rational response to the deregulation of the financial

system, allowing consumers to smooth their consumption more efficiently over

their life cycle...Lower inflation, leading to lower nominal interest rates, has

also made it easier for households to borrow more.

Treasury stated that the

increased ability to borrow (which is a function of both deregulation and lower

interest rates) probably helped drive up house prices, increasing the amount

that households needed to borrow.[213]

The ANZ bank had a similar

view, stating that debt levels had been driven by 'a sustained boom in house

prices, a sustained low interest rate environment and solid growth in household

incomes'[214].

The RBA's view is that the

main reason debt has risen is that households can afford to borrow more in a

low interest rate environment. The Bank also points out that in a low inflation

environment, the real value of loans is eroded more slowly than when inflation

is high; and financial deregulation has played a significant role, increasing

lender competition and providing innovations such as home equity loans and

redraw facilities.[215]

All commentators agree

that increased investor activity in the housing market has further increased

demand in the market, contributing significantly to increases in housing prices

and household debt levels.

Some commentators consider

that banks and other finance providers may also have influenced demand by

increasing the amount of money available to the market, aggressive promotion of

lending products and allowing lending standards to slip in a bid to maintain

profits and market share. This view is disputed by lenders who maintain that

the borrowing is entirely driven by demand factors, which the lending

institutions merely find more creative ways of satisfying.

Wealth effects, whereby

households feel encouraged to spend on the basis of perceived increased wealth

resulting from increased house prices, may also have had an effect on debt

levels.

The rise in household debt

is also partly attributable to the increase in the number of additional people

who have borrowed money in response to the above factors. The RBA notes that

the number of households with owner-occupied housing debt appears to have

increased by over 40 per cent since 1996, considerably faster than the growth

in the number of households.[216]

The housing boom

As the Governor of the RBA

observed in 2003:

The story about household debt is largely a story about housing

and, of course, is intimately tied up with the subject of rising house prices.[217]

Australian house prices

are at a historical high, having more than doubled since 1996. This rise was

particularly pronounced in the period between March 2001 and March 2004, with

around 40 per cent of the rise in the last decade occurring in that period.

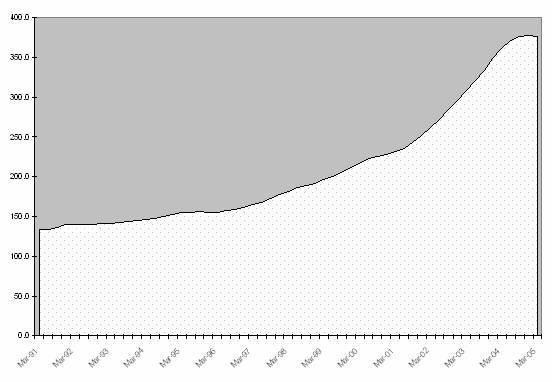

Figure 1 below shows the rise in house prices since March 1991.

Figure 1: Median Price Established Houses Sold ($000)

Weighted average 8 capital cities –

average of previous 4 quarters

Source: Parliamentary Library

housing data derived from Real Estate Institute of Australia, Market Facts.

An alternative way of

considering the increase in house prices is to compare how much these have

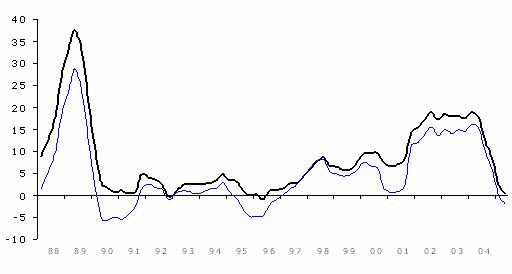

changed from previous years. Figure 2 shows this change in prices as a percentage,

expressed in nominal and real terms. The graph puts the recent increases in

house prices in context, showing that this was not the first occasion when

large price movements have happened.

In the massive boom of the

late 1980s, prices increased in one year by 40 per cent. The rate of increase

has been less during the current boom, but has been sustained over a long

period. It has also been seen consistently across the country. As observed by

the Productivity Commission, 'the upswing in housing prices since the mid-1990s has been bigger and more

widespread than in previous cycles'[218].

Figure 2: House prices over the last 17 years (Nominal and real terms)

showing the percentage change from the previous year.

Source: ABS, reproduced from

Submission 17, ANZ Bank.

But why have house prices

risen? Housing prices behave in accordance with the basic principles of supply

and demand. Put simply, demand for housing forces prices up if supply falls

short of what the market needs. During this boom, growth in demand has

outstripped the growth in supply. Construction of new dwellings, while at very

high levels, has not kept pace with the rise in the number of households and

investors seeking to buy properties.

There is evidence that the

boom in house prices has come to an end, and that a cooling off in the market

is taking place. Treasury advised the Committee that the housing cycle is

unwinding, and that as this market cools, growth in dwelling investment and

consumer spending should ease and household saving rise.[219]

The RBA also believes that

the boom in prices for housing has come to an end in most capital cities. In

its August 2005 Statement on Monetary Policy, the RBA published the following

table (Table 1), which shows a fall in Sydney prices and low or static prices

except in Perth and Adelaide. A feature of this table is that the RBA is now

able to publish statistics that are stratified by market segment, and are a

more reliable indicator of what is happening in the market.

Table 1:

Composition-adjusted house prices – percentage change

| |

18 Months

to Dec qtr 2003 |

18 Months

to June qtr 2005 |

|

Sydney |

25 |

-7 |

|

Melbourne |

20 |

0 |

|

Brisbane |

62 |

5 |

|

Adelaide |

35 |

9 |

|

Perth |

33 |

19 |

|

Canberra |

41 |

0 |

|

Australia |

29 |

0 |

Source: RBA, Statement on monetary policy, August

2005.

The RBA also notes that

lending for housing remains above its 2004 average, but has softened in recent

months. While housing credit growth was still running at an annualized rate of

10.9 per cent in the six months to June 2005 this is half the peak rate of

2003.[220]

Deregulation of the financial system

The most fundamental

change that occurred as a result of the deregulation of the financial section

was that instead of governments attempting to regulate the operation of

financial markets through supply-side measures, demand became the main factor

influencing the amount of money borrowed. This was well summed up by the

Australian Bankers Association (ABA) in its submission:

A central tenet of the financial sector deregulation achieved in

Australia over

the past two decades has been the removal of iniquitous credit rationing that

had previously prevailed, thereby allowing policy to influence credit through

demand-side factors. [221]

Deregulation had a number of significant

effects, including:

-

removal of restrictions on lending;

-

increased competition between lenders, further

enhanced by the entry of foreign banks and non-traditional lenders into the

market; and

-

innovation increased, leading to a much wider

range of financial products becoming available to borrowers.

Enhanced competition

between lenders resulting from deregulation has also reduced borrowing costs by

putting downward pressure on interest rates and operating margins. Treasury

advised that competition within the sector has brought about a reduction of

interest rate margins from 3.6 per cent in 1994 to 1.8 per cent in 2004.[222]

Competition encouraged

innovation, leading to the introduction of financial products that are more

flexible and can be tailored to the needs of a wider group of consumers, making

them more attractive to borrowers. Developments in the mortgage market are a

good example. Treasury advised the Committee that in 1980 there were 26 types

of mortgages available and that deposit-taking institutions were the main

source of home finance. By 2003, approximately 3000 differentiated mortgage

products were available to consumers.[223]

A number of new

institutions also now offer housing finance, although banks retain 85 per cent

of the market. According to the ABA, about 10 percent of all home loans are now

provided by non-conforming lenders, that is, lenders who are not subject to

APRA's prudential supervision because they do not take deposits.[224] This group includes lenders such as

mortgage originators, of whom Aussie Home Loans is a well-known example.

Non-conforming lenders raise money by issuing securities in the money market to

raise funds for lending, a process known as securitisation.

The ABA

argued that while the market share of non-conforming lenders is still

relatively small, its influence is considerable, and has led to the

introduction into the banking sector of a number of new financial products such

as 'low-doc' loans which originated in the non-conforming sector.[225]

Mortgage brokers have also

entered the Australian housing market and have made a significant impact.

Mortgage brokers are essentially middlemen between borrowers and lenders whose

role is to find and arrange home loans for customers. The ABA told the

committee that this group now represent about 30 per cent of the housing loan

market, and their presence has exerted downward pressure on interest rates:

...I understand that

mortgage brokers constitute about 30 per cent of the market...As a result of

financial deregulation initiated by various governments, mortgage brokers are a

fact of life. They have certainly assisted in the downward pressure on interest

rates and, I guess from a customer viewpoint, they have proven to be a good

thing.[226]

Other significant

innovations in the housing loan market include mortgage insurance, which allows

a lending institution to lend where income-to-repayment ratios exceed 30 per

cent, or where the buyer has less than the required deposit; and home equity

loans, which enable a home owner to access equity and can be used for a range

of purposes including the purchase of property for investment purposes.

A natural consequence of

deregulation is that finance is available to many more people, increasing

demand. As Treasury pointed out in its submission, this increased ability to

borrow has probably helped to drive up house prices, which in turn increased

the amounts households needed to borrow.

Interest rates and inflation

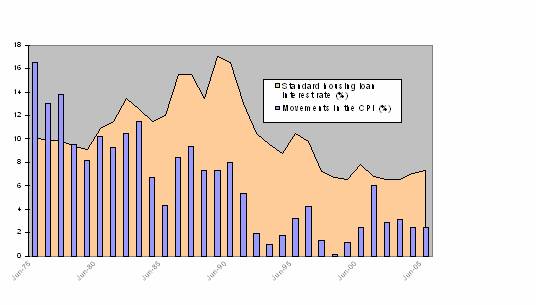

Australian interest rates

have declined steadily for the last fifteen years, and have been consistently

low for most of the last decade. As shown in Figure 3, interest rates charged

by the banks for housing mortgages declined steeply from their 1989 peak of 17

per cent, and have remained low by Australian standards for most of the last

decade.

This reduction in interest

rates has a close relationship with the decline of inflation. As Treasury noted

in its submission to the inquiry, lower inflation, leading to lower nominal

interest rates, has made it easier for households to borrow more. However this increased ability to borrow

'probably helped to drive up house prices, thereby increasing the amount

households needed to borrow'.[227]

Figure 3: Housing

loan interest rate and movements in the CPI 1975 – 2005.[228]

Source:

RBA

A fall in interest rates

also places mortgage finance within reach of a larger proportion of the

population, some of whom would not have previously qualified for a loan under

the income tests that lenders traditionally applied to borrowers.

The ABA

advised the Committee that traditionally, the standard income test that a bank

applies is that the monthly loan repayment should not exceed 30 per cent of

gross income. Higher income individuals may qualify for a higher ratio. This

income test is applied 'conservatively', incorporating an interest rate buffer

of one or two per cent.[229]

The Productivity

Commission quantified the increase in borrowing capacity that has resulted from

lower interest rates in its report First

Home Ownership, observing that average borrowing capacity over the last

five years was about 70 per cent higher than for the period 1983 to 1993[230].

There is evidence that the

increased affordability that results from low interest rates has also affected

buyer preferences, and many previous home owners have traded up to better,

larger homes in more desirable areas. New homes are also significantly larger

on average than houses built a decade ago. In its report First home ownership, the Productivity Commission explains this

effect succinctly:

For owner-occupiers, a halving of the interest rate almost

doubles the mortgage potentially obtainable, as well as nearly doubling the

price of a home that a home that can be 'afforded' for a given budget or

income.[231]

The RBA agrees that debt

has risen because households can afford to borrow more, but points out that a

low inflation environment also means that households hold their debt for

longer. This is because the real value of the debt is not eroded as fast as it is

in a high inflation environment. The RBA considers that these two factors (low

interest and slower debt erosion) could account for an approximate doubling of

the debt-to-income ratio.[232]

Investor activity in the housing market

Significantly higher

investment activity in the housing market is an important factor adding to

housing demand. Investor activity increases buyer competition and, as a result,

prices.

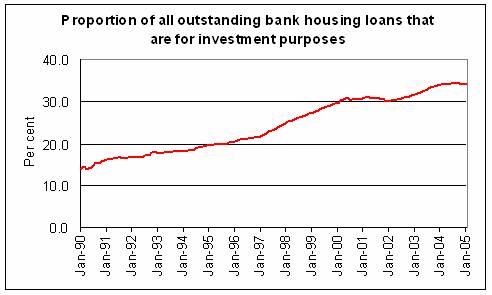

As shown in Figure 4, investment

loans as a proportion of total outstanding housing loans have grown from around

15% in 1990 to about 34% in 2005. This

growth has slowed in response to the softening of the property market since

2004.

Figure 4: Proportion of bank housing loans for investment property.

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletins.

While Australia

(70%) has roughly the same rate of home ownership as the UK

(69%), the USA

(67%) and Canada

(64%) it has a significantly higher rate of ownership of investment

property. About 13% of Australian

households receive rental income (up from about 9% a decade ago), compared with

about 6.5% in both the USA

and Canada, and

2% in the UK.[233]

The rise in property investment

appears to have been driven by a number of factors, including:

-

Perceptions that this is a profitable activity,

anticipating capital appreciation;

-

Taxation considerations (eg: negative gearing,

favourable capital gains tax treatment);

-

The availability of a range of diversified

banking products particularly suited to investors (eg home equity loans); and

-

Money more freely accessible as a result of

financial sector deregulation.

The Productivity

Commission identified a 'supportive' tax environment and aggressive marketing

of property investment 'opportunities'

among the factors that further stimulated the investor-driven component of the

demand for housing.[234]

The RBA has expressed

particular concern about the rise of investor activity in the housing market,

warning that many people were more exposed to risk than they perhaps realised.

Income and employment growth

A number of commentators,

including the ANZ and the Productivity Commission, have identified rising

household incomes and employment rates as contributing to rises in demand for

housing and price rises.[235]

In its report First Home Ownership, the Productivity

Commission pointed out that aggregate household income had increased in real

terms by 2.8 per cent a year since 1992-93, while real disposable income

increased by an average rate of 1.2 per cent per year.

In the same period, the

number of people in full time jobs increased by approximately one million, an

average increase of 1.5 per cent per year.[236]

The Commission argued that

as income and employment rise, more people have the capacity to purchase

housing, and existing owners have increased capacity to trade up to higher

quality housing if that is their preference.

The Commission's research

indicated that the link between rising incomes and employment and rising house

prices was significant, although difficult to disentangle from other demand

side factors. However, it concluded that:

Nevertheless, it seems incontrovertible that income and

employment growth have underpinned growth in housing demand in Australia

since the 1990s, which has in turn placed upward pressure on prices.[237]

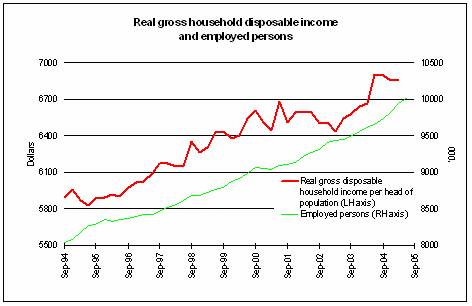

Figure 5 shows the growth

in incomes and employment over the last decade. While rising incomes may have

added to the demand for housing, they have not kept pace with the rise in debt,

which increased substantially relative to income.

Figure 5: Growth in

real income and employment 1994 – 2005

Source: ABS

Lending policies and practices of finance providers

There seems little doubt

that the lending policies and practices of banks and other financial

institutions contributed to increased demand for housing finance and thereby

household debt. However, the extent of the impact which this had is

debated. Chapter 5 of the report

explores this area in more depth.

Wealth effects

The housing boom of the

past few years resulted in substantial wealth gains in many Australian

households as existing houses were revalued upwards. The ANZ estimates that net

household wealth has increased by 45 per cent over the last three years.[238] This increase in valuations has

given rise to what commentators describe as a 'wealth effect', which is

considered to have been a factor in increasing household debt.

The Governor of the RBA, Mr

Macfarlane, described the wealth effect in

the following terms:

Recent evidence from

several countries including Australia shows that during periods when house prices

are rising rapidly households tend to react to this by increasing their

consumption faster than their income—that is, they reduce their savings. They

can do this either by reducing discretionary saving or by borrowing against the

equity in their house to finance non-housing expenditure, a process referred to

as housing equity withdrawal. This process occurred in Australia particularly in 2002 and 2003. [239]

The ANZ maintains that the

wealth effect has both monetary and psychological dimensions. In a monetary

sense, households whose property values have increased substantially are able

to tap into that wealth through a range of new loan products such as home

equity loans. From a psychological

perspective, increases in property prices make households feel wealthier and

more comfortable about dipping into savings or borrowing more.

The ANZ estimates that the

wealth effect increased household consumption growth from 4.2 per cent to 6.2

per cent for the March quarter 2004, and observed that the impact of this

effect takes up to 18 months to become fully reflected in household

consumption.[240] The ANZ's

observations are consistent with research by the RBA.

A research study conducted

by the Economic Research Department of the RBA in 2003 confirmed that the

wealth effect is significant in driving household expenditure, although the

study did not extend to whether overall debt levels increased as a result. That

study drew comparisons between stock market wealth and housing wealth:

For our preferred model, a one dollar permanent increase in

stock market wealth is estimated to increase annual consumption by 6 to 9 cents

in the long run and a similar increase in housing wealth is estimated to

increase consumption by around 3 cents. Since households' housing assets are

more than three times as large as stock market assets, our estimates imply that

a one per cent increase n housing wealth has an effect on aggregate consumption

that is at least as large as that of a one per cent increase in stock market

wealth.[241]

A manifestation of wealth effects, the use of home equity loans, has

been identified by the RBA as adding to the risks faced by those households who

use them. Households are generally acknowledged as being most at risk early in

the period of a loan, this risk being diminished as the principle is repaid and

incomes rise. The RBA has pointed out that in a low inflation environment,

households stay in this risk zone for longer because incomes rise more slowly.

The use of equity loans can further prolong the risk period as the principle

may be topped up from time to time instead of being paid out.[242]

The RBA considers that the wealth effect may have dissipated somewhat as

a result of recent developments in the housing market:

In a world where dwelling prices have stopped rising and even

declined somewhat, perceptions of ongoing rapid increases in wealth are

presumably now in the process of dissipating. This will weaken positive wealth

effects, and could possibly lead to a partial reversal in time. On the other

hand, the earlier increases in dwelling prices were very large, and even with

the latest data showing declines, a big cumulative rise in wealth has occurred

over the past decade, most of which has not been tapped. So there may yet be

some expansionary impetus in the pipeline from those earlier gains.[243]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents