Chapter 3

Issues raised

3.1 The submissions received by the committee raised a number of issues about the provisions and implementation of the Temporary Budget Repair Levy (the Levy), which this chapter will discuss in turn.

3.2 First, in brief, it will outline submissions that were broadly supportive of the Levy's introduction. It will then outline the concerns submitters raised about the Levy, which included:

- its short timeframe and temporary nature;

- perceived flaws in the Levy's design, including adding potential complexity to the tax system and providing opportunities for tax minimisation opportunities;

- potential implementation issues for the superannuation industry; and

- failure to address inequities in the broader tax system.

Support for repairing the budget

3.3 A number of submissions recognised the importance of 'restoring Australia's public finances to a sustainable condition'.[1] For example, the Grattan Institute stated:

Perhaps the most important argument for budget reform is that deficits borrow from the future. They require future generations of taxpayers to pay for today's spending. There are fundamental issues of intergenerational fairness if future taxpayers are forced to bear the burden of today’s spending that they do not have a say in, nor benefit from.[2]

3.4 In this regard, it is important to note that according to government estimates, the debt is heading for $667 billion unless the government takes corrective action.[3]

Support for the Levy

3.5 The committee received some evidence voicing support for the Levy.

3.6 The Australia Institute considered that the Levy would begin to address growing inequality in Australia, particularly the widening gap in income levels between the highest and lowest earners.[4] While it supported the levy, the Institute wanted the government to go further to make the levy permanent.[5]

3.7 Mr Saul Eslake stated the Levy's design would not affect Australia's economic activity or labour force participation negatively.[6] Moreover, Mr Eslake supported

'the notion that the "burden" of restoring Australia's public finances to a sustainable condition should be (and should be seen to be) "fairly shared" as between different stakeholders', particularly through changes to the tax system to target high income earners.[7]

3.8 However, Mr Eslake thought the Levy was not 'the best way to achieve this goal' and suggested more effective and equitable tax measures could be found

to ensure high income earners contributed to 'Budget repair'.[8]

3.9 Although the Grattan Institute argued that the Levy does not meet all of the criteria of effective budget repair, it does meet some. The Levy:

- is being introduced quickly;

- has a reasonably clear explanation and rationale;

- ensures that tax as well as spending is part of the solution; and

- those on high incomes make some contribution to fixing the budget.[9]

Criticisms of the Levy

The Levy's timeframe

3.10 Taxpayers Australia considered the Levy's implementation period was too short to make a real contribution to 'Budget repair'. Its submission contended that the Levy will end right at the time government spending pressures will be particularly high and need some support:

Estimates released by Treasury show public debt accelerating rapidly over the period 2018–2023 but we note that the Debt Tax is scheduled to end in 2017. The $3.1bn which Treasury estimates the tax will raise contributes little to the repair of the budget and contributes nothing in the period when action is most required (post 2017).[10]

3.11 The Australia Institute argued the Levy should be a permanent feature of Australian income tax scales, rather than a temporary measure ending in mid-2017.[11] Its submission encouraged the government to consider 'incorporating it into the regular income tax scales and perhaps increasing the top marginal rate over time'.[12]

3.12 Along similar lines, the Grattan Institute noted that the Levy fails on one of the most important criteria for effective budget repair—it has no impact on the long term structural position of the Budget, as it will cease in 2017–2018.[13]

3.13 In regard to this criticism, the committee believes that it is imperative to keep in mind the broader sweep of budget measures. The minister explained that the government's focus has been on pursuing structural savings and structural reforms, mostly on the spending side but also on the revenue side:

Re-introducing indexation of the fuel excise, for example, is a structural reform on the revenue side. But the virtue and challenge that comes with structural reforms is that they start low and slow and build over time. So the judgement that the government made was that there was a need for an immediate effort to get us into a stronger starting position as we set out to repair the budget for the medium to long term. In order to do that, we did make some decisions in relation to immediate savings on the spending side and some immediate additional effort on the revenue side. Over the forward estimates, about 80 per cent of the budget repair effort comes from spending reductions and just over 20 per cent comes from revenue increases.[14]

3.14 According to the minister, the temporary budget repair levy is part of the short-term, immediate effort to get Australia into a stronger starting position 'to repair the budget mess that we have inherited'. He then explained that 'beyond that three-year period, progressively, the structural savings and the structural reforms will continue to build'.[15]

Flaws in Levy's design

Introducing complexities into the tax system

3.15 The Tax Institute expressed the view the Levy would create unnecessary complexity in the Australian tax system, which would create a burden of compliance for taxpayers while not substantially increasing tax returns for government.[16]

3.16 It suggested the bills would introduce unnecessary complexity to the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 by the addition of three steps to calculate a taxpayer's basic income tax liability.[17] The Institute's submission stated:

Section 4–10 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (the Tax Act) works out how much tax you must pay, and the calculation consists of four steps. Three additional steps are required to the calculation in order implement the Levy. The Levy is not included in calculating the taxpayer's basic income tax liability under Step 2 of the method statement in section 4–10(3) of the Tax Act. Instead a further 3 Steps are required to adjust the calculation in the method statement in order to take into account the Levy: see section

4–11(3) inserted by Item 2 of Tax Laws Amendment (Temporary Budget Repair Levy) Bill 2014. A note to section 4–10(3) is to be inserted to remind the relevant taxpayers that they must pay the Levy in addition to the income tax liability that they have calculated under section 4–10(3).

The rationale behind treating the Levy as a further adjustment to the section 4–10(3) calculation is to ensure that the Levy cannot be offset by non-refundable tax offsets except the foreign income tax offset: Explanatory Memorandum at para 1.14. We would expect that the number of non-refundable tax offsets available to those earning taxable income exceeding $180,000 would be limited. If there is no substantial increase in the tax collected, we question the practical utility of adding this complexity to the calculation of the individual's income tax liability under section 4–10(3).[18]

3.17 Additionally, the Tax Institute considered that the bills would add a discrepancy to the Income Tax Rates Act 1986. It outlined the situation in its submission:

...the increase in the top rate of tax appears to apply inconsistently. Amendments to the Income Tax Rates Act 1986 (the Rates Act) in Items 35 and 36 Income Tax Rates Amendment (Temporary Budget Repair Levy) Bill 2014 increase references to 45% in certain provisions of the Rates Act by 2%. These Items do not include a reference section 12(1) and Schedule 7 of the Rates Act. This has the effect that the rate of tax on superannuation remainders and employment termination remainders under section 1(a) and (aa) of Schedule 7 of the Rates Act remain at 45%. The rationale for this discrepancy is not explained in the Explanatory Memorandum.[19]

3.18 The committee received advice from Treasury about whether the Levy added any unnecessary complexity to the tax system. Treasury stated that 'Our view is that changes to the income tax system are among the simplest of tax changes'.[20]

3.19 Moreover, Treasury suggested there was more than enough time for high income taxpayers to recalculate their tax liabilities for 2014–15 to incorporate the Levy, especially considering they would also have to incorporate the new Medicare Levy rate from 1 July 2014.[21]

Tax minimisation and arbitrage opportunities

3.20 Some submissions to the inquiry argued the Levy's design contained opportunities for high income earners to minimise their tax liabilities. For instance, Mr Eslake's submission suggested the Levy could be avoided by most high income earners through:

... greater use of the myriad provisions in the income tax system which offer preferential or concessional treatment for particular types of income, forms of business organization or categories of investment vehicles.[22]

3.21 Taxpayers Australia shared this view, commenting that 'only the wealthy but poorly advised will be paying the Debt Tax'.[23] It contended that the Treasury's projections for the tax raising $3.1 billion over three years may be overstated, as:

...considerable amounts of relatively straightforward tax planning is likely to take place which have the effect of reducing taxable income, often to beneath the $180,000 threshold.[24]

3.22 According to Taxpayers Australia, many tax advisers are already actively marketing strategies to avoid the Levy, including:

- accelerating tax receipts or tax deductible expenditures into years where tax relief is available or the Levy is not active;

- deferring tax receipts or tax deductible expenditures into years where tax relief is available or the Levy is not active;

- exploiting the misalignment between the financial and FBT years through salary packaging programs;

- increasing contributions to superannuation funds, which will continue to be taxed at 15 per cent, and so reducing taxable income below the Levy's threshold; and

- using family trusts to split and stream incomes across the beneficiaries of the trusts (e.g. children and spouses), to lower tax liabilities and reduce the main earner's income below the Levy's threshold.[25]

3.23 The committee received advice from Treasury about general tax minimisation or avoidance behaviours potentially encouraged by the introduction of the Levy.

3.24 Treasury stated that a central feature of the Australian tax system was a degree of flexibility in the way taxpayers could receive payments in different years or through different entities.[26] Treasury argued that, even if this flexibility could reduce the tax liabilities of some individuals, 'there are substantial limits on this flexibility':

As with elsewhere in the tax system, should individuals abuse this flexibility and seek to put in place arrangements driven solely by tax benefit, their behaviour will constitute tax avoidance and be subject to the general anti-avoidance rules in Part IVA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936.[27]

3.25 The Treasury informed the committee that there were 'specific anti-avoidance rules directed at preventing taxpayers from re-arranging their affairs to gain a tax benefit in the manner raised in submissions.' such measures include 'rules in relation to the alienation of personal services income, pre-paid outgoings and advance expenditure'.[28]

Misalignment with the Fringe Benefits Tax system

3.26 Some submitters noted the opportunities high income earners will have to exploit the Levy's misalignment with the FBT system through the use of salary packaging and fringe benefits schemes. This would both reduce their taxable income and impose a lower rate of tax on money they put into these schemes.

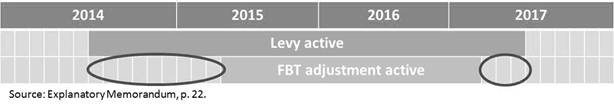

3.27 The Levy will be active across financial years, and so will commence on 1 July 2014, whereas adjustments to FBT settings will align with the Fringe Benefits year, and so will be introduced on 1 April 2015. Similarly, the Levy will end on 31 June 2017, whereas FBT adjustments will end three months before this on 31 March 2017.

3.28 As a result, FBT rates will be 2 per cent lower than the top marginal rate (including the Levy and Medicare Levy) in periods highlighted in the following timeline.

3.29 This discrepancy was noted by Hayes Knight, who highlighted the reduction of government revenues that would come from the increased use of salary sacrificing programs by high income earners in these periods.[29]

3.30 Taxpayers Australia also highlighted the arbitrage opportunities this offers taxpayers on the top marginal rate and noted the potential lost revenues for government this represents.[30]

3.31 Looking at this issue from a tax policy and a compliance point of view, Mr Rob Heferen, from the Treasury suggested that 'given that the FBT rate is going to change, the probability of people restructuring affairs for nine months in order to have to move back is pretty minimal'.[31] He explained:

There are costs in entering into such arrangements. So that balanced with the idea of having separate FBT rates for the one FBT year, and this happens because the FBT year...is from 1 April to 31 March. That would introduce quite significant costs to taxpayers and employers. Given that there is only going to be nine months, in essence, it is really the flood levy story again.[32]

3.32 Mr Heferen emphasised the fact that the compliance costs for employers and employees, 'in grappling with that change for the 2014–15 year, would be quite significant'. He was not aware of any time where the FBT rate has been changed out of alignment with the FBT year.[33]

3.33 The committee also requested additional written advice from Treasury about the potential effects of the mismatch between financial and fringe benefits cycles. In its written response, Treasury indicated that this mismatch was a well-established feature of the tax system, so had been considered in the Levy's design. The Treasury provided the following advice:

While the rate of fringe benefits tax is aligned with the highest marginal rate of income tax applicable to individuals (plus the rate of the Medicare levy), the income tax and fringe benefits tax have always applied over different annual periods. As these periods differ, to have any rate apply over the same period would require at least one tax to have a split period in which two different rates would apply.[34]

3.34 Treasury's written advice also confirmed the assessment that delaying the introduction of the higher FBT rate until the 2015–16 FBT year would avoid imposing a burden of compliance on businesses and employers, which would be caused by demanding they calculate part-year fringe benefits for their employees.[35] Furthermore, it reinforced the argument that 'the small size and temporary nature of the levy would limit the likelihood of taxpayers taking action to avoid the levy'.[36]

Effects on the superannuation system

3.35 Some submitters, including ASFA, and the Tax Institute,[37] discussed the amendments to the superannuation system made by the bills, and raised two potential negative effects:

- the superannuation industry would have difficulty implementing the Levy, due to the short timeframe between the policy announcement in the

2014–15 Budget on 13 May 2014 and the implementation date of 1 July 2014; and

- unintended inequity introduced into the superannuation system by amendments to excess non-concessional contribution arrangements.[38]

3.36 The Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia Limited (ASFA) expressed the concern that the superannuation industry may struggle to implement the Levy by the start of the 2014–15 financial year.[39]

3.37 ASFA explained that superannuation entities have a more complex tax collection process than individuals and employers, which involves superannuation companies calculating and deducting tax imposts from member benefits payments before they are paid (rather than tax being deducted from an employee's pay based on the ATO's assessment of their 2013-14 income). Therefore, the introduction of the Levy would mean:

For the superannuation industry...the appropriate tax will need to be deducted from benefit payments that are paid from 1 July 2014 as failure to do so would result in the incidence of the tax falling on the superannuation trustee.[40]

3.38 ASFA highlighted two situations that would particularly affect the superannuation industry:

The two examples of this, which create implications for superannuation entities, are the provisions relating to Departing Australia Superannuation Payments (DASP) and the tax levied on the no-[Tax File Number] contributions income of funds.[41]

3.39 On the basis of these concerns, ASFA requested the commencement date of the bill relating to Departing Australia Superannuation Payments be delayed until 1 October 2014, to allow the industry sufficient time to adapt. Moreover, they requested the non-Tax File Number component of the new legislation not apply to superannuation funds.[42]

3.40 The Tax Institute raised another issue: the bills may unintentionally introduce inequity into the superannuation system that would particularly affect members of Defined Benefits Funds. Its submission outlined the problem:

Amendments in the Superannuation (Excess Non-concessional Contributions Tax) Amendment (Temporary Budget Repair Levy) Bill 2014 and paragraphs 1.70 to 1.72 of the Explanatory Memorandum indicate that tax rate applying to excess non-concessional contributions tax will increase from 47 to 49 per cent of an individual's excess non-concessional contributions for a financial year. The Tax Institute is concerned that this will result in inequity, particularly for members of Defined Benefit Funds. Employees in some funds routinely exceed the cap through no fault of their own as they have no control over what is paid in by their employer by reason of an award. Those in Defined Benefit Funds are unable to have the sum returned to them to avoid the excess and therefore cannot take advantage of the amendment announced in the 2014–15 Budget whereby those non-concessional contributions withdrawn from a fund can be taxed at the individual's marginal rate. Instead, members of Defined Benefit Funds, (who may not be on the highest marginal tax rate) would be taxed at 49% on these deemed excess contributions which they might never receive.

The rate of tax on non-complying superannuation funds will increase from 45 per cent to 47 per cent, as will the rate of tax on the non-arm's length component of the taxable income of a superannuation fund. As with the rate change to Excess Non-Concessional Contributions Tax, this will impact taxpayers who are not on the highest marginal rate of tax.[43]

3.41 3.23 The committee received advice from Treasury about the potential repercussions of the Levy's introduction on the superannuation system that were discussed in submissions.

3.42 Treasury responded to the concerns ASFA raised about implementation timeframes and equity issues. Regarding the timeframe for the Levy's introduction, Treasury noted that many tax changes had been announced on Budget night for application in the next financial year and that the resulting 'burden...for taxpayers, especially sophisticated taxpayers, is minor'.[44]

3.43 Regarding ASFA's proposed adjustment to Departing Australia Superannuation Payments, Treasury stated that:

...having different rates applying for different parts of the tax year creates significant compliance burdens. Further, having a different rate apply for particular amounts, especially when, as with Departing Australia Superannuation Payments, the timing of payments is largely within the control of the taxpayer, poses integrity risks and is therefore generally inappropriate.[45]

3.44 Treasury also responded to the concerns raised by the Tax Institute about the Levy's effects on Excess Non-Concessional Contributions Tax, by noting:

...work is underway to implement the Government's 2014–15 Budget announcement to provide a mechanism to ensure individuals are not excessively taxed and we expect the Government will consult closely with the sector to ensure appropriate relief is available to all taxpayers with excess non-concessional contributions.[46]

Conclusion

3.45 The committee understands that in order 'to repair the budget and deliver important structural reforms' that would 'facilitate future growth in living standards', the government was asking all Australians, including high income earners, to contribute to achieving a healthy budget.

3.46 The committee has considered all the concerns that were raised by submissions and received expert advice on these matters from the Treasury.

3.47 Some submitters were concerned the Levy's introduction would encourage tax minimisation or avoidance by taxpayers. The committee considers the Levy will not encourage undue tax minimisation or avoidance behaviours by Australian taxpayers, as the Levy's design intentionally adjusts a number of tax rates to reflect the introduction of the Levy. These adjustments have been proposed to reduce potential opportunities for taxpayers to avoid their tax liabilities.

3.48 The committee acknowledges the adjustments to FBT are scheduled to begin after the introduction of the Levy, and that this may result in some tax avoidance behaviour by taxpayers. However, the committee supports the decision to adjust FBT in line with the Fringe Benefits Year rather than the financial year, as this will avoid imposing undue compliance costs and increasing unnecessary red tape for businesses and employers.

3.49 Overall, the committee supports the introduction of the temporary Levy. The Levy will ensure high income earners will make a contribution to the government's Budget Repair Strategy, which was announced in the 2014–15 Budget.

3.50 The committee considers the Levy is a simple and reasonable measure in the 2014-15 Budget context; it is entirely appropriate for the government to ask all Australians to make a contribution to Budget repair when they can afford to do so.

3.51 The committee supports the targeting of the measure to the highest income earners, so that the most vulnerable Australians are protected. The committee notes the threshold of $180,000 was chosen so almost none of the Australians affected by expenditure cuts to direct assistance in the 2014-15 Budget, such as family payments and pensions, would be liable to pay the Levy.

3.52 Moreover, the committee supports the progressiveness of the Levy, which would also ensure taxpayers who are better off will contribute a little more to the repair of the Budget, based on their ability to pay.

Recommendation 1

3.53 The committee recommends that the Senate pass the bills.

Senator David Bushby

Chair

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page