Chapter 4

Sovereign wealth funds and state-owned entities

4.1

The terms of reference for the inquiry directed the committee to examine

both the international and Australian experience of sovereign wealth funds

(SWFs) and state-owned entities (SOEs). In this chapter the committee turns to outline

the recent emergence of SWFs and SOEs before then examining the effectiveness

of Australia's regulatory system for managing foreign investment applications

by sovereign wealth funds and state-owned entities.

4.2

In recent years the rapid accumulation of assets in various countries

has resulted in the growing number of SWFs. SWFs have emerged as a key player

in the international capital markets and SWFs are currently estimated to hold

close to $US3 trillion in assets.[1]

Evidence received by the committee suggested that their presence is set to grow

with the IMF estimating that SWFs could grow to about US$12 trillion by 2012.[2]

In their submission, Dr Malcolm

Cook and Mr Mark Thirlwell, Lowy Institute for International Policy, referred

to SWFs as a 'move towards state capitalism'.[3]

4.3

The Future

Fund's Chairman Mr David Murray AO, explained from where the money contained in

SWFs has been sourced:

...75 per cent of the money in sovereign wealth funds, as far

as I can assess it, is oil sourced, about 20 per cent export surplus sourced

and about five per cent budget surplus sourced. Australia would be in that last

category.[4]

4.4

Mr Murray also explained that some nations establish SWFs because they

are resources dependant while others establish SWFs because they are export

surplus countries. Resource dependent countries like the United Arab Emirates,

Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Norway and Brunei look to protect themselves from

resource depletion by setting up significant SWFs for the long term.

4.5

Dr Brian Fisher, Concept Economics, referred to this as 'rents from

exhaustible resources'. He suggested that these 'rents' could be used

productively to ensure intergenerational equity through drawing on the annual

output from the capital stock:

There is a vast amount of economic literature on this very

interesting subject that goes back a long time and, in fact, led the Norwegians

to establish their oil investment fund. Basically, their view was that you can

either have the oil in the ground and save it up until some point in the future

or you can exploit it and put a proportion of the rent into some fund, invest

the money and earn interest on the money. Under reasonable conditions those two

things are potentially equivalent. Much of the economic literature talks about

what is the optimal trajectory for the exploitation of a non-renewable resource

such as oil.

The theory is relatively straightforward, but in the

practical world where we have uncertainty about what future demand is for a

particular commodity the practice is a little bit more difficult. In the case

of iron ore, for example, it is unlikely that there is going to be, in the near

term, lots of substitutes for steel, so we are going to end up using lots of

iron ore into the future, and it just so happens, luckily, that there is lots

of iron ore on the planet as well, so we are unlikely to run out of the stuff

in the short term or even the very long term...

If, for example, you decide to store a product in the ground

like oil and somebody turns up with a nice substitute, all of a sudden you are

sitting on some black stuff that five years ago was very valuable and now all

of a sudden is not very valuable at all...It is much more difficult to think

about intergenerational equity than just saying that we will save the iron ore

for future generations. It might actually be much more efficient to sell to the

Chinese, Japanese and the Koreans iron ore today and put the rent in the bank

or in your super fund, save it that way and then pass it on to future generations.[5]

4.6

The other category of SWF referred to by Mr Murray is that established

by export surplus countries:

In the case of export surplus countries, they simply arrive

at a situation, for various reasons, where their foreign reserves are much

larger than could normally be expected to be needed in their central bank for

the normal reserve purposes...They often split their funds into either wealth

funds or budget stabilisation funds, in addition to what is held for

international purposes in the central bank...In Australia's case, we are working

off favourable terms of trade over a considerable period in which we had budget

surpluses and we have chosen to set those aside in the interests of better

public sector savings specifically to deal with the likely budget situation

from 2020 and beyond with ageing of the population.[6]

4.7

At the Budget Estimates hearing of June 2009, Mr Patrick Colmer

explained that FIRB had not identified any significant problems with SWFs in

Australia:

The experience that we have had with sovereign wealth funds

goes back many years. There has been some very recent attention on sovereign

wealth funds. Our experience over quite a few years has been that, generally

speaking, we have not identified any problems with sovereign wealth funds in

the way that they operate in Australia.[7]

Characteristics of SWFs

4.8

Mr David Murray—who along with being the Future Fund's Chairman of Board

of Guardians is also Chairman of the newly formed International Forum of

Sovereign Wealth Funds—suggested that their were three distinguishing features

of a SWF:

-

It has a defined special purpose;

-

Its assets are held for the community and not individual

interest; and

-

It invests in financial assets.[8]

4.9

The International Working Group on Sovereign Wealth Funds draws

attention to the status and behaviour of SWFs:

-

In their home countries, SWFs are institutions of central

importance in helping to improve the management of public finances and achieve

macroeconomic stability, and in supporting high-quality growth;

-

In many instances they take a long term view of investment and

'ride out' business cycles, bringing important diversity to global financial

markets.[9]

Examples of Sovereign Wealth Funds

Abu Dhabi Investment Authority

4.10

Established in 1976, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority's (ADIA) principal

funding source is from a financial surplus from oil exports. The ADIA replaced

the Financial Investments Board which was created in 1967 as part of the then

Abu Dhabi Ministry of Finance. It is the largest SWF; it is wholly owned and

subject to supervision by the government of Abu Dhabi. The fund is an

independent legal identity with full capacity to act in fulfilling its

statutory mandate and objectives. As much as 75 per cent of its assets are administered

by external managers.

4.11

ADIA's funding sources derive from oil, specifically from the Abu Dhabi

National Oil Company (ADNOC) and its subsidiaries which pay a dividend to help

fund the ADIA and its sister fund Abu Dhabi Investment Council (ADIC).

Established in 2006, the Abu Dhabi Investment Council has a local and regional

focus and holds stakes in two large state owned banks, Abu Dhabi Commercial

Bank and the National Bank of Abu Dhabi.[10]

Singapore's Temasek Holdings

4.12

Created in 1974, Singapore's Temasek Holdings is a SWF which primarily focuses

on Asia and Singapore. Temasek holds significant stakes in the major

corporations: Merrill Lynch, Barclays Bank and SingTel. (SingTel, who owns

Optus is majority owned by Temasek Holdings, which holds 54 per cent of

SingTel's issued share capital.) The Lowy Institute for International Policy

suggests that Singapore has been the regional leader in 'creating new

investment vehicles to manage the accumulation of a diversified portfolio of

foreign assets'.[11]

China Investment Corporation (CIC)

4.13

The China Investment Corporation (CIC) was established in September

2007. Modelled on Singapore's Temasek Holdings, the CIC is responsible for

managing part of China's foreign exchange reserves. It is responsible for

managing China's $200 billion sovereign wealth fund. To date it has made

substantial investments in financial firms. The previous vehicle, state-owned

Central Huijin Investment Limited, was merged into the new company as a

wholly-owned subsidiary company. Typically there is a separate entity that is

interposed to manage investments on behalf of the CIC. The Lowy Institute for

International Policy explains that two-thirds of the CIC's investment portfolio

is expected to be targeted at recapitalising the domestic financial sector with

only one-third for investment overseas, mostly through fund managers.[12]

Australian Government Future Fund

4.14

Established in 2006, the Australian Government Future Fund, or pension

fund, is an independently managed investment fund into which the Australian government

has deposited fiscal surpluses. The purpose of the fund is to meet the

government's future liabilities for the payment of superannuation to retired

public employees. The stated aim of the fund is to hold $140 billion by 2020;

this figure would free up $7 billion in superannuation payments each year from

the federal budget.

4.15

The Future Fund was established by the Future Fund Act 2006 to

assist future Australian governments meet the cost of public sector

superannuation liabilities by delivering investment returns on contributions to

the Fund. Investment of the Future Fund is the responsibility of the Future

Fund Board of Guardians with the support of the Future Fund Management Agency.

From 1 January 2009, the Board of Guardians gained responsibility for the

investment of the assets of the Education Investment Fund (EIF), the Building

Australia Fund (BAF) and the Health and Hospitals Fund (HHF).

4.16

The Board is collectively responsible for the investment decisions

relating to the special purpose public funds and is accountable to the government

for the safekeeping and performance of those assets. As such, the Board's

primary role is to set the strategic direction of the investment activities of

the funds consistent with the Investment Mandate for each fund. The Board is

supported in its functions by the Future Fund Management Agency. The Agency is

responsible for the development of recommendations to the Board on the most

appropriate investment strategy for each fund and for the implementation of

these strategies. All administrative and operational functions associated with

the management of the funds are undertaken by the Agency.[13]

The Future Fund invests in an array of assets and as at 31 March 2009 the

Future Fund assets (including Telstra shares valued at $6.8 billion) are $58.1

billion.[14]

4.17

Mr Murray was question by the committee as to whether the Future Fund

may look to invest in resource and infrastructure projects within Australia

into the future, to which he responded:

To achieve our objective we need to invest in an array of

assets. We do that by building a strategic asset allocation that, in our

opinion, is likely to meet the return objective we have been given in our

mandate from the government. We, therefore, need to have some diversity of

assets but, given the type of return target we have, infrastructure investments

will be an important component and Australian equities will be an important

component. By investing in Australian equities we would be an important

investor in Australian mining companies.[15]

4.18

The committee also notes that numerous submitters to the inquiry

recommended that Australian entities, in particular the Future Fund and

superannuation funds, look to invest more in Australia's resource sector,

arguing that this would reduce the sector's reliance on foreign capital.[16]

Largest

Sovereign Wealth Funds (in US$ Billions)[17]

|

Country |

Fund(s) |

Size |

|

UAE |

Abu Dhabi Investment Authority |

704 |

|

Norway |

Government Pension Fund |

379 |

|

Singapore |

Government Investment

Corporation/ Temasek Holdings |

378 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

No designated name |

287 |

|

Kuwait |

Revenue Fund for Future

Generations/ Government Reserve Fund |

222 |

|

China |

China Investment Corporation |

218 |

|

Russia |

Reserve Fund/ National Welfare

Fund |

158 |

|

Australia |

Australian Future Fund |

101 |

|

Libya |

Libya Investment Corporation |

86 |

|

Algeria |

Reserve Fund/ Revenue

Regulation Fund |

56 |

|

USA |

Alaska Permanent Reserve Fund |

50 |

|

Qatar |

State Reserve Fund/

Stabilisation Fund |

44 |

|

Brunei |

Brunei Investment Authority |

43 |

|

Korea |

Korea Investment Corporation |

31 |

|

Kazakhstan |

National Fund |

30 |

International Working Group of Sovereign Wealth Funds and the Santiago

Principles

4.19

The International Working Group (IWG) comprises 26 IMF member countries

with SWFs.[18]

They were formed to identify and draft a set of generally accepted principles

and practices (GAPP) that properly reflect their investment practices and

objectives. These investment practices and objectives have come to be embodied

in the Santiago Principles. Mr David Murray informed the committee about the

development of the Group:

I would like to point to the history of development of that

group. When there was first fairly serious concern in the US and Europe about

investments from sovereign wealth funds into predominantly western countries

the IMF, through its representative ministers, formed an international working

group of sovereign wealth funds and set out to form an agreed standard of

practices dealing with sovereign wealth funds, which eventually became the

Santiago principles. Australia was a supporter of that process through its IMF

representative minister, the Treasurer, and the guiding objectives for those

principles were to help maintain a stable global financial system and free flow

of capital investment to comply with all applicable regulatory and disclosure

requirements in the countries in which sovereign wealth funds invest, to invest

on the basis of economic and financial risk and return-related considerations,

and to have in place transparent and sound governance structures.[19]

4.20

The Santiago Principles are the generally accepted principles and

practices of the International Working Group of Sovereign Wealth Funds. As

suggested above, the Santiago Principles were a response to pressure,

particularly from the U.S. Congress, through the IMF, to create a set of

principles which, if adhered to would give recipient countries of foreign

investment comfort that those sovereign wealth funds acted more from commercial

principles than any other principles. They also sought to provide a framework

that reflects appropriate governance, accountability and transparency

arrangements. Mr Murray added: 'The publication of those principles has gone a

long way to placate some of the critics of sovereign wealth funds'.[20]

There are 24 generally accepted principles and practices. These were

established on 11 October 2008 and can be found at: http://www.iwg-swf.org/pubs/gapplist.htm.

International Forum of Sovereign

Wealth Funds

4.21

In April 2009 the International Working Group of Sovereign Wealth Funds

established the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds through the

'Kuwait Declaration'. The Forum is a voluntary group of SWFs that seeks to

provide the opportunity for SWFs to meet, exchange views on issues of common

interest, and facilitate an understanding of the Santiago Principles and SWF

activities. The Forum does not seek to be a formal supranational authority and

its work does not carry any legal force.[21]

4.22

The purpose of the Forum is to act as a platform for:

-

Exchanging ideas and views among SWFs and with other relevant

parties. These will cover, inter alia, issues such as trends and developments

pertaining to SWF activities, risk management, investment regimes, market and

institutional conditions affecting investment operations, and interactions with

the economic and financial stability framework;

-

Sharing views on the application of the Santiago Principles

including operational and technical matters; and

-

Encouraging cooperation with investment recipient countries,

relevant international organisations, and capital market functionaries to

identify potential risks that may affect cross-border investments, and to

foster a non-discriminatory, constructive and mutually beneficial investment

environment.[22]

4.23

This has proved another endeavour to establish international frameworks for

SWFs to help develop confidence across the international community.

Committee view

4.24

The committee notes that while concern has been expressed about the size

and power of SWFs the evidence obtained by the committee does not point to any

significant concern about the investments or behaviour of SWFs. By contrast,

the majority of the concerns that were raised over the course of the inquiry

related to the investment activities of state-owned entities. Some submitters

classified SWFs and SOEs in the same terms. The committee saw this as

problematic and recognised that, by and large, they represent two distinct

types of investment activity.

4.25

While the committee welcomes the fact that organisations like the International

Working Group of Sovereign Wealth Funds have sought to codify the behaviours of

SWFs, through establishing a set of core principles related to governance,

accountability and transparency, the committee believes that the best way for

Australia to regulate the conduct of foreign investors (be they SWF, SOE or private

commercial operator), is through developing robust domestic legislation.

State-owned entities

4.26

SOEs are distinguished from SWF by their institutional closeness to the

state. SOEs are a legal entity created by a government to undertake commercial

or business activities on behalf of the owner government. Like SWFs, SOEs may

have access to funds that often exceed that available to private commercial

interests and they may have levels of influence and power that extends beyond

many large multinational companies. What distinguishes SOEs from SWFs are some

of the features of SWFs outlined above. Moreover, the International Working

Group of Sovereign Wealth Funds has also sought to distinguish SWFs from SOEs

through the Santiago Principles in terms of their standards of public

disclosure, governance frameworks and reporting requirements.[23]

4.27

Professor Peter Drysdale and Professor Christopher Findlay point out

that there may be substantial variation in the character and operations of SOEs

and that SOEs operate under a range of policy regimes:

State-owned enterprises operate under different policy

regimes in different countries. The regime under which Swedish state-owned

enterprise operates may be different from that under which Chinese or Indian

state-owned enterprise operates. Do these differences affect the impact of

investment from these different sources? And the regime under which state-owned

enterprise operates changes over time, as it clearly has changed and is

changing in China. Do these changes need to inform the strategy that host

countries might adopt towards FDI from this source?[24]

4.28

There is concern the foreign governments might not act in the same way

as private investors—they may be more explicitly political in their behaviour

and may seek to exert influence in ways that extend beyond seeking to protect

their investment. Beyond concerns about the power, size and scope of SOEs,

various submitters to the inquiry expressed concerns about the effect

investment by SOEs may have on: corporate governance, competition and national

security. These arguments are outlined below.

Corporate governance

4.29

There have been criticisms that operators of SOEs lack transparency and

accountability. Board members may find themselves representing two sets of

interests—those of the SWF/ SOE and those of the company on whose board they

sit:

...if you have board members appointed by the foreign owned

enterprise ... (t)hat person may have divided loyalties towards the target

company or the Australian company and the foreign country that appoints them.

This notion of a separate legal entity is well established in our corporate law

system, but it may not be so well established in other legal systems where if

you sit as a board member you have a duty to that company solely. This issue of

divided loyalties is being dealt with under corporate law in Australia, whereas

the person may have those divided loyalties and it may be hard to pin those

down.[25]

4.30

However, Fortescue Metals Group, who as outlined above, recently

accepted a deal worth $650 million which saw Hunan Valin assume a 17.55 per

cent stake in the company, informed the committee of steps they had taken to

reduce or eliminate the prospect of any such conflict:

...when Fortescue sought investment and got investment from Hunan

Valin, we were quite clear to restrict their shareholding, their board

positions and their ability to look through to our costs...So we were quite

clear: yes, they could be on the board; yes, they could be part of discussions,

but if it involved anything to do with our cost or pricing structure they would

have to excuse themselves from the discussion and not be circulated with any of

the relevant information...

The other thing that we did was ensure that the

representative on our board was a specified person. The reason for that was

some concern on our part that the Chinese can at times send a subordinate to

fulfil the role, he can be difficult and then, when you have argued with them

and argued with them, ultimately they say, 'Sorry, he wasn't really authorised

to do that', and they pull him out and put somebody else in. Our view was that

the way to control that was to make sure that it is actually the chairman of

Hunan Valin who is on our board and that he is not allowed to send an

alternate. That means that whatever he says he has to stand by.

4.31

Mr Tapp further explained that as a result of their investment they

obtained the right to have one board member but were not allowed a

representative on any of the subcommittees. Moreover, that as a condition of

FIRB approval, Valin was required to sign up to Fortescue's code of conduct.

While this would have been required under the Companies Act, because it was

attached to the FIRB approval, it was given additional weight.[26]

4.32

Writing about Chinese SOEs, Dr Ann Kent has also raised concerns about

both the differences in corporate culture and the enforcement of insider

trading laws. In the first instance she explains: it is not simply that

businessmen can become politicians without election but that the relationship

between commerce and officialdom in China is much more complex and fluid than

Australia. In the second, when referring to the proposed Chinalco acquisition

of an interest in Rio Tinto, she suggests that while board members 'would be

subject to our laws by virtue of their board positions and under Australian

insider trading laws, the enforcement of such obligations is poor in both

Australia and China'.[27]

4.33

By contrast, IPA suggests that while there has been a 'perception of

risk' associated with SOEs, appropriate regulation would see that Australian

interests are protected:

In Australia an SOE only enjoys the same commercial

environment as any other investor. And the Australian government maintains the

right to appropriately regulate where there may be a perceived risk from an

external SOE investor. For example, the government can do so by ensuring that

the standards of corporate governance for firms listed on the Australian Stock

Exchange are rigorous and prevent large controlling shareholders from looting

the firm’s assets or expropriating firm value from minority shareholders. Given

appropriate corporate governance standards, large controlling shareholders need

not pose any investment threat or any other type of threat to Australia. With

appropriate shareholder protection all investment would be in the national

interest.[28]

4.34

This position was reinforced by evidence provided by Mr Patrick Colmer

who reiterated that all Australian law applies to equally to all investors:

It is important to recognise that an investor in this country

will be subject to the industrial law, to the environmental law, to the health

and safety law. All the Australian laws apply equally to a foreign investor

once they are established in the country as they do to any other company

operating in this country.[29]

4.35

Dr Brian Fisher, Concept Economics, suggested therefore that it was up

to Australia to develop adequate regulatory frameworks for foreign investors:

What this really comes back to is ensuring that our domestic

legislation holds everyone to the same playing field. It does not matter who

owns the company just as long as the OH&S rules, environment rules and the

competition rules—all of those things—apply to those entities equally and we

make sure that there is no improper transfer pricing and so on. That really comes

down to our domestic arrangements. In my view, this is more about domestic

settings than it is about attempted control of the initial investment.[30]

Competition

4.36

The committee also heard concerns about competition and market

manipulation in instances where buyers gain control over the supply chain. In

relation to Chinese investment in the Australian resource sector, there is

criticism that the Chinese government will use pricing information obtained

through their association with the target company in their future contract

negotiations. Associate Professor Zumbo suggested that this could result in

manipulation or discriminatory pricing, that:

-

benefit state-owned companies

that are customers of the Australian target company, or (ii) benefit customers

from the country sponsoring the sovereign wealth fund or which controls the

state-owned companies. Such discriminatory practices would be detrimental to

other customers of the Australian target company competing with those favoured

customers from the country sponsoring the sovereign wealth fund or which

controls the state-owned companies.[31]

4.37

Associate Professor Zumbo also raised concerns about patterned strategic

acquisitions—whereby a SWF or SOE seeks to acquire a series of companies within

the same sector in order to gain a controlling stake in certain sectors of the

economy. This, he suggests, would limit or remove the freedom of action of

those target companies to negotiate with competitors and may ultimately result

in forcing up prices for domestic consumers. Beyond the domestic market,

Associate Professor Zumbo suggests that 'the process of creeping acquisitions

in the same sector on a global scale would pose a very real and considerable

danger to competition and consumers around the world'.[32]

Concern over patterned or creeping acquisitions in the resources sector was

also raised by Mr William Edwards:

The areas where they are showing most interest in buying our

assets are those that involve inputs into their own economy, so that they are

able to exercise a stranglehold. There is a consistency to the pattern of their

investment elsewhere in the world, and that is to get a stranglehold on things,

particularly natural resources.[33]

Committee view

4.38

The committee acknowledges that the legislation identifies a substantial

interest is where a person, alone or together with any associate(s), is in a

position to control not less than 15 per cent of the voting power or holds

interests in not less than 15 per cent of the issued shares of a corporation.

It also notes that the legislation identifies an aggregate substantial interest

as an instance where one or more persons together with any associate(s), are in

a position to control not less than 40 per cent of the voting power or hold

interests in not less than 40 per cent of the issued shares, of a corporation.[34].

4.39

The committee also notes that if a SOE sought to acquire a series of

companies within the same sector, in order to gain a controlling stake in

certain sectors of the economy, then the ACCC could rule against successive

acquisitions on the basis that they were anticompetitive. Section 50 of the

Trades Practices Act prohibits mergers and acquisitions that would be likely to

have the effect of substantially lessening competition in a market in

Australia. The committee also believes that the Treasurer would also have the

power to prevent such acquisitions if he believed they were against the

national interest.

Benchmark pricing regime for iron

ore

4.40

Prices for iron ore are largely determined by the benchmark pricing

system, whereby producers negotiate with consumers and agree on a price that

will prevail for the following year. Price is affected as much by supply and

demand as it is determined by the effectiveness of the two parties' negotiating

position. While participants often regard this system as flawed, and companies

like BHP-Billiton have withdrawn from annual benchmark pricing negotiations,

progress towards a more transparent market pricing system has been limited. Fortescue

identified the repercussions this might have for partner/ buyers.

The point I want to make about this is that having

information about the cost structure of Australian entities could potentially

be damaging to those undertaking benchmark negotiations. It is not clear how

long the benchmark system will continue to run. But certainly our view is that

for the Japanese joint ventures, to the extent that they have had a look

through to mining costs, that has favoured them when it comes to the annual

benchmark negotiations because they have an understanding of what the cost

position of the person they are negotiating with is.

The issue at stake here is that, ultimately if uncommercial

expansion takes place for the purpose of driving down the price, that will be

damaging to Australia's national interest.[35]

4.41

In order to protect their interests, Mr Tapp explained that Fortescue

were quite clear to restrict Hunan Valin's 'shareholding, their board positions

and their ability to look through to our costs' and they (given the way the

investment has been structured) 'see no threat'.[36]

Therefore, to protect Fortescue's bargaining position in price negotiations,

they limited Chinese access to price sensitive materials that may be used in

benchmark pricing negotiations. Mr Tapp went further in identifying the way in

which Fortescue have eliminated the capacity of the owner/ buyer to drive the

price down:

As far as we are concerned, what was imposed on Hunan Valin

was entirely consistent with our own corporate code of conduct and entirely

consistent with the Corporations Act. If you are a director of a company, you

have a duty to declare when you have a conflict of interest. If you are on that

board representing the Chinese government or, indeed, a steel mill, you have a

conflict of interest when it comes to negotiating the price. So we were quite

clear: yes, they could be on the board; yes, they could be part of discussions,

but if it involved anything to do with our cost or pricing structure they would

have to excuse themselves from the discussion and not be circulated with any of

the relevant information...

I will be quite clear about what our fear is: investment in

expanding production for the sole purpose of increasing supply to drive the

price down. That is not something you can do unless you control the entity. It

is not something you can do if you only control a very small entity.

Clearly, when large companies like Fortescue, Rio or BHP are

involved, they are able to increase their production to the point where they

can have a material impact on the overall supply situation. I would not want to

see a situation where somebody else controlled them to the extent that they had

the ability to demand that they expand production. Even though that would be

bad for the company, it would ultimately be good for the customer. If you are

the Chinese government and you own both the company and most of the steel

mills, it can be in your interest to engage in such commercial activity.[37]

Committee view

4.42

The committee notes with interest the evidence offered by the Fortescue

Metals Group and considers it a useful example of where conditions may be

placed on SOEs where it is believed there is potential for some type of

commercial conflict.

National security and geo-strategic

concerns

4.43

The fifth principle contained in the Treasurer's Guidelines for Foreign

Investment Proposals focuses on national security:

An investment may impact on Australia's national security.

The Government would consider the extent to which investments

might affect Australia's ability to protect its strategic and security

interests.

4.44

Recently the Treasurer ruled against the Minmetals $2.6 billion bid for

OZ Minerals in March 2009 on national security grounds as the Prominent Hill

copper/gold mine was deemed to be within the Woomera Prohibited Area of South

Australia, a weapons testing range. Subsequently the terms of the deal were

revised, omitting the Prominent Hill mine and the Treasurer approved the

application.

4.45

With respect to Chinese investment in Australia, it is worth noting that

traditionally Australia's most important trading partners have also been its security

partners. They have also been democracies. Mark Thirlwell, Lowy Institute for

International Policy, notes:

A further important complication is (geo-) political.

Traditionally Australia’s most important trading partners have also been our

key security partner (the UK and then the US)—or at least an ally of our key

security partner (Japan), all of them democracies. Now for the first time our

largest trading partner is authoritarian, a quasi-mercantilist, and a strategic

competitor of our major ally.[38]

4.46

Others submitters did not see the national security concerns

explicitly linked to security. Rather they referred to the way in which Chinese

acquisitions would result in a gradual erosion of Australian sovereignty. This

concern has been outlined above.[39]

Additional concerns about Chinese

SOEs

4.47

Many of the concerns related to Chinese foreign investment were similar

to those related to foreign investment generally. These typically relate to

issues of transparency; conflict of interest (wherein the seller becomes a

buyer); loss of control over natural resources in a time of global resource

scarcity; and concern over whether the Chinese government might not act in the

same way as a private investor. China-specific concerns related to: the fact

that Chinese SOEs are considered to be government controlled; the ceding of

sensitive technologies to a potential military competitor; and the human rights

record of the Chinese government and by extension its state-owned entities. The

Leader of the Opposition, Malcolm Turnbull, has raised two further concerns:

one related to the transfers of assets, the other related to matters of

mutuality.[40]

4.48

Others have a more extreme position arguing that the operations of

Chinese SOEs are part of a strategic campaign by a non-democratic nation to

undermine the Australian economy and threaten Australian sovereignty. A number

of submitters to the inquiry articulated this strategic dominance/ Trojan horse

thesis. The National Civic Council warned that China's emergence as a hegemonic

economic power presents an acute challenge to Australia's national security and

that Australia risks falling victim to China's strategic dominance through its

foreign investment.[41]

Chinese capital and China's outbound investment

4.49

For some years the People's Republic of China (PRC) has been acquiring

very significant foreign reserves. The PRC currently has around US$2 trillion

in foreign exchange reserves in US currency or US Treasury bonds. In addition

to the US$200 billion sovereign wealth fund, which is managed by the China

Investment Corporation (CIC), China also has the National Social Security Fund

(NSSF, $U.S. 80 billion). The NSSF collects pension contributions and the

proceeds of state assets and has signalled that it would explore further

investments offshore.

4.50

The Chinese market accounts for one third of global demand and two

thirds of global demand growth in industrial metals. China consumes over a

third of the world's aluminium, over a quarter of the world's copper and over

half of the world's seaborne iron ore.[42]

China's domestic iron ore resources cover less than 50 per cent of demand.

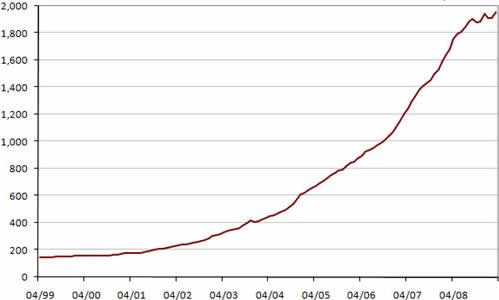

Chinese

foreign reserves (US billions)[43]

4.51

Therefore, it is not surprising that China is considering ways of

diversifying its investments through securing investment in the international

resource sector. With so much money, at a time of scare global liquidity, the

Chinese government is actively encouraging its domestic entities to diversify

and explore overseas opportunities—particularly in the energy and resource

sector. Resource-rich nations like Australia and Canada have become the focus

of China's strategic efforts.

China's 'going out' strategy

4.52

China's recent foreign investment activity has been prompted by the

announcement, at the Chinese Communist Party's Sixteenth Congress in 2002, that

the Chinese leadership was encouraging Chinese companies to 'zou chuqu'—step

out into the global economy, not only through exports, but also by investing

overseas. Professor Peter Drysdale offered the following context for this

strategy:

They are undertaking this investment in the context of what

is called in China a 'going out' strategy, which is a policy that released the

controls on foreign investment abroad and encouraged Chinese enterprise to take

up stakes in foreign companies and undertake foreign investment, and foreign

investment has grown rapidly under that policy.[44]

4.53

Professor Drysdale went on to explain how China's State-owned Assets

Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council has been

charged, since 2003, with devolving responsibility of SOEs; making SOEs

implement corporate governance reforms and having SOEs conform to commercial

market disciplines:

Since 2003 the State-owned Assets Supervision and

Administration Commission of the State Council, SASAC, in China has assumed the

responsibility for exercising ownership of state owned enterprises on behalf of

the Chinese government. SASAC has two important roles. It supervises the key

state enterprises and their management; it exercises a monetary role in their

profit and management performance. Its second important role is that it carries

forward the reform of state owned enterprises. It has the responsibility for

reforming state owned enterprises, the privatisation of state owned

enterprises, their governance and their consolidation. All of these things are

also a main responsibility for SASAC.[45]

4.54

Professor Drysdale's argument extended further suggesting that it was

important for Australia to engage these enterprises because it offers an

opportunity to influence them and introduce them to the Australian system.[46]

Commercial imperatives of Chinese SOEs

4.55

The committee received evidence that those Chinese companies seeking to

invest in Australia display highly commercial orientations. The Australia China

Business Council suggested that there is 'growing evidence that corporate China

is behaving commercially, or, as the Chinese would say, they are following a

policy of "zhengqi fenkai"—proper separation of government

functions from business operations'.[47]

In speaking of his personal experience dealing with Chinese SOEs Mr Douglas

Ritchie, Rio Tinto, explained:

I have to say that not only do I find them commercial in

their approach but I find that their standards, in terms of employment,

occupational health and safety and attitudes to environment, are every bit as

good as those of equivalent corporations elsewhere. I would also say that I

have found that the people who manage these corporations manage them in exactly

the same way as people like me manage our own corporations and they are judged

in exactly the same way. That has to do with return on investment and the

standards that one maintains that relate to the standards that the corporation

itself sets. So I think that a lot of these fears that you express, Chair, as

being around the place come from primarily, and unfortunately, a lack of

familiarity with these state owned enterprises by the people who are making

these comments.[48]

Chinese

investment in Australia by industry, as approved by the Foreign Investment

Review Board (FIRB) 1992–2007[49]

|

Year |

Number |

Agriculture,

forestry and fisheries

($A

million) |

Manufacturing |

Mineral

exploration and resource processing |

Real

estate |

Services

and tourism |

Total |

|

1993–94 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

1994–95 |

927 |

0 |

1 |

42 |

426 |

52 |

522 |

|

1995–96 |

267 |

0 |

6 |

52 |

137 |

31 |

225 |

|

1996–97 |

102 |

10 |

3 |

5 |

176 |

17 |

210 |

|

1997–98 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

1998–99 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

1999–00 |

259 |

35 |

5 |

450 |

212 |

10 |

720 |

|

2000–01 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

2001–02 |

237 |

0 |

47 |

20 |

234 |

10 |

311 |

|

2002–03 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

2003–04 |

170 |

0 |

2 |

971 |

121 |

5 |

1,100 |

|

2004–05 |

206 |

2 |

0 |

39 |

181 |

42 |

264 |

|

2005–06 |

437 |

0 |

223 |

6,758 |

279 |

0 |

7,259 |

|

2006–07 |

874 |

15 |

700 |

1,203 |

712 |

11 |

2,640 |

4.56

The committee also received evidence that characterised Chinese

companies very differently. The National Civic Council suggested:

...Chinese corporations—at least government-owned

corporations—are not only government owned but these corporations are

overwhelmingly state-run monopolies in which the key positions are appointed

not just by the government but by a sole party which runs the government, which

is the Chinese Communist Party.[50]

4.57

Referring to the size of China's SWF, the Farmers from the Liverpool

Plains suggested that the Chinese government were 'wandering around the world...picking

the eyes out of pretty well anything they can find and having a go at

purchasing it'.[51]

Regulation of SOEs

4.58

Australia's guidelines for assessing foreign investment applications by

foreign governments are similar to those for private sector proposals; however,

they do identify some differences. In a February 2008 statement titled,

'Government improves transparency of foreign investment screening process'

Treasurer Swan stated:

Proposed investments by foreign governments and their

agencies (for example, state-owned enterprises and sovereign wealth funds

(SWF)) are assessed on the same basis as private sector proposals. National

interest implications are determined on a case-by-case basis.

However, the fact that these investors are owned or

controlled by a foreign government raises additional factors that must also be

examined.

This reflects the fact that investors with links to foreign

governments may not operate solely in accordance with normal commercial

considerations and may instead pursue broader political or strategic objectives

that could be contrary to Australia’s national interest.

The Government is obliged under the Foreign Acquisitions

and Takeovers Act 1975 to determine whether proposed foreign acquisitions

are consistent with Australia’s national interest.[52]

4.59

The committee received varying evidence related to the government's

guidelines for assessing investment by sovereign wealth funds and state-owned

entities. Professors Drysdale and Findlay raised concern about the government's

new guidelines arguing that 'the elaboration of these principles was somewhat

damaging to Australia's foreign investment climate'. They suggest that the

government's statement that 'investors owned or controlled by a foreign

government raise additional factors that must also be examined', has the effect

of discriminating specifically against Chinese investment proposals and creates

uncertainty about Australia's foreign investment policy. Moreover, that through

creating a class of investments which require special scrutiny Australia has

departed from a 'well-established and respected case-by-case approach'.[53]

Rio Tinto had a different view explaining it 'supports the six principles set

out by the Treasurer in February 2008 for screening investments linked to

foreign governments'.[54]

4.60

The committee received strong evidence suggesting that the government

must act to ensure the appropriate legislative and regulatory frameworks are in

place for assessing applications from SOEs. The IPA suggested:

Rather than fearing investment from SOEs, the Australian

government should be: ensuring the appropriate legislative and regulatory

frameworks are in place to ensure investors act appropriately; and liberalising

the Australian investment regulatory regime to ensure Australia is an

attractive destination for investment capital.[55]

4.61

In its submission, the Lowy Institute for International Policy explained

that while they view the emergence of new sources of foreign capital as

positive for Australia they believe that a greater degree of regulatory

oversight is required in the case of foreign investment by

government-controlled entities:

In our judgment, the present regulatory and policy framework

for foreign investment applications is robust enough to manage this growing

trend and provides a reasonable balance between Australia's openness to foreign

investment and the responsibility of the government to ensure that economic and

commercial change in Australia is in line with community interests and

concerns. This framework's long-standing distinction between private sector

foreign investment and investment originating from state-owned entities is both

justifiable...[56]

We also believe, however, that a greater degree of regulatory

oversight in the case of foreign investment by government-controlled entities

compared to that applied to private foreign investment is warranted.[57]

4.62

Arguing that as Australia seeks new forms of capital investment from

overseas it needs to come to terms with applications from state-owned entities,

Professors Drysdale and Findlay suggested:

There is no reason in principle why state-owned foreign firms

will not deliver benefits to Australia or other host countries to foreign

investment of a kind that is similar to those delivered by private owned

foreign corporations. Technological advantages, management know-how, market

ties, capital costs or other advantages that come with FDI can be associated

with state-owned firms and support their competitiveness and viability in the

same way as they do with private multinational corporations. It would therefore

be unusual if the ownership of foreign investors was germane to approval of

their investment. In seeking to secure supplies and establish relationships

that are important to integrated operations across a resource supply chain or

to exploit marketing advantages, an investment involving state ownership would

be behaving no differently than many privately owned investments.[58]

4.63

By extension, they posit that 'there are no issues that cannot be dealt

with under the umbrella test of national interest in managing the growth in

Chinese FDI into the Australian minerals sector'.[59]

Professors Drysdale and Findlay identify three main 'additional factors' that

could demand a test of suitability beyond the 'national interest':

-

FDI investments involving state ownership and dominant

shareholding and control might be used to serve as a vehicle for shifting

profits back to the home country through underpricing exports.

-

FDI investments involving state ownership and dominant

shareholding and control might be used to serve as an instrument for

subsidising the development of 'excess capacity' or 'extra-marginal' projects

and ratchetting resource prices down.

-

FDI investments involving state ownership and dominant

shareholding and control might be used to pursue political or strategic goals

inconsistent with the efficient development and marketing of national

resources.

4.64

However, they conclude that in each case a 'national interest' test

provides adequate protection.[60]

Dr Malcolm Cook, Lowy Institute for International Policy, similarly stated:

...we think the existing regulatory framework before an

investment review board and within that the differentiation made between

private sector for an investment into Australia above 15 per cent and foreign

investment by state owned entities is justified. Our basic view is that it is not

broken so there is no real need to fix it.[61]

4.65

This perspective was reiterated by Mr Mark Thirlwell, Lowy Institute for

International Policy:

It is not clear to me what falls through the gaps of the

existing system, what additional tool we would need or what additional review

processes we would need that is not already provided for in the existing

framework.[62]

4.66

Mr Stephen Creese, Rio Tinto, also offered the following advice for

determining the independence of SOEs

We think there is a subset of questions that really need to

be asked about independence from the government from which the state owned

enterprise springs. We say you have to go down to the real nitty-gritty

questions of control. Can the state owned enterprise actually control operating

assets through its investment? Can it actually influence and control key

business decisions about such things as capital investments, product mix,

production levels, pricing, contracting strategies, marketing and those things?

You need to go down to that level of detail. If you answer, 'Yes, they can',

then you have got to say, 'Now we understand the detail of how that might work

in the context of that particular transaction, is this contrary to the national

interest in terms of the way that would operate?' So we think there is a more

detailed level of inquiry than simply looking at: is it 'independent'?[63]

4.67

While suggesting that there was no need for wholesale conceptual reform,

the Australia China Business Council suggested that the Foreign Acquisitions

and Takeovers Act should be tightened so that:

...the policy requirements in relation to investments by SWFs

and SOEs (are incorporated) into the body of the Foreign Acquisitions and

Takeovers Act to avoid arguments that the policy requirements may be beyond the

ambit of the FATA...[64]

4.68

By contrast, the committee also heard several calls for the reform of

FIRB and for increasing the regulation of foreign investment by SOEs. These

included:

-

Establishing an authority that is separate from the FIRB to

control and administer the investment of sovereign funds into Australia,

especially into the mining and resource sector.[65]

-

Abolishing the case-by-case approach to better manage creeping

acquisitions by SOEs.[66]

-

Establishing more restrictive caps on foreign acquisitions/ ownership

within specific strategic sectors (the mining industry, prime agricultural

land) where a certain percentage of capitalisation should not exceed a certain

level.[67]

-

Giving FIRB to power to examine licenses issued by state

governments.[68]

Committee view

4.69

Historically, one of the reasons Australia has relied upon foreign

investment is because it has had shallow domestic capital markets. This

continues to be the case particularly when it comes to capital intensive

sectors such as the mining industry. The committee considers that it is

critical that Australia continue to be seen as a country that welcomes foreign

investment and remains an attractive and competitive place to invest. The

committee believes that foreign investment is critical to the development of

Australia's industries and infrastructure and has significant benefits for the

Australian community at large.

4.70

The committee also believes that the best way for Australia to manage

the new capital flows that have stemmed from the emergence of SWFs and SOEs is

through developing robust domestic legislation. The committee has acknowledged

that the FATA legislation could be tightened to deal with complex acquisitions

where takeovers of smaller strategic assets may be masked by an application

which, in total, does not represent more than 15 per cent, and therefore does

not trigger review. As suggested above, the committee would like FIRB to give

adequate consideration to the interaction between the various components of a

total acquisition.

4.71

As has been suggested throughout this chapter, much of the evidence

received by the committee argued that the current system for assessing foreign

investment applications is adequate. Nevertheless, the committee also heard a

range of other opinions which suggested that the current system was either too

restrictive or not restrictive enough. The committee notes that while the

Treasurer's recent announcement to increase the thresholds for reviewing

applications from $100 million to $219 million may be welcomed by those seeking

a more liberal foreign investment regime; it will be of serious concern to

others. The committee notes that those who are critical of the current system,

and who would like the thresholds for reviewing foreign investment applications

lowered, have particular concern over how these higher thresholds may be used

to assist companies or state-owned entities acquire assets in a patterned or

strategic manner which may give them an opportunity to engage in the

manipulation of pricing, particularly in the resource sector.

4.72

The committee believes that the current regulatory framework for

assessing foreign investment proposals, whether they are made by private

commercial interests, sovereign wealth funds or state-owned entities, is

sufficient. The committee considers that the combined powers of the Foreign

Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975, Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers

Regulations 1989, Trade Practices Act 1974 and laws related to transfer

pricing and environmental and worker protection, are sufficient to provide for

the robust assessment of foreign investment applications and satisfactory

regulation of the conduct of foreign investors. The committee is also of the

belief that, having considered all the evidence, the system of case-by-case

assessment, based on the national interest, has also served Australia well.

Senator Alan

Eggleston

Chair

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page