Minority Report

Preface

1.1

The Committee has already issued two reports on

the Mass Marketed Tax Effective Schemes fiasco.

1.2

The first – the Interim Report (June 2001) – was

highly critical of the ATO’s management of and approach to the mass marketed

schemes affair.

1.3

The second report (September 2001) proposed an

alternative resolution and settlement option with a view to allowing taxpayers

and the ATO to resolve their differences without proceeding to court.

1.4

The recommended resolution and settlement was

proposed following consultations with taxpayers and the ATO.

1.5

Despite giving a commitment to respond to the

second report promptly, the ATO are yet to advise the Committee of their views

on the recommendations.

1.6

Many of the issues canvassed in the Interim

Report have become clearer and only add to the concerns initially raised by the

Committee.

1.7

The ATO is the manager of Australian Taxation

Law and as such is required to interpret and apply those laws – fairly and

equitably.

1.8

Under the self-assessment tax system, taxpayers

are required to abide by the law and the ATO view of the law, although they do

have a right to challenge the ATO view in the Courts.

1.9

This type of system places great onus on the ATO

to ensure clarity in both the law and their view of the law.

1.10

The ATO’s task can be made more difficult by

government policy objectives, which may impact on the application of the law.

1.11

The mass marketed schemes debacle is a good

example of how things can go horribly wrong where a lack of clarity and action

exists.

1.12

There is no question that ATO administrative

practices have been found wanting on these matters for some time.

Background

1.13

Evidence to the Committee clearly shows that the

ATO was aware of problems associated with claimed deductions in mass marketed

schemes as early as 1982.

1.14

Indeed the ATO audited some twenty-eight schemes

between 1987 and 1997. Fourteen of those audits were completed by 1994 with

nine schemes having deductions disallowed primarily on the basis of round robin

non-recourse financing.

1.15

As can be seen from the table below, scheme

deductions grew at an exponential rate from 1993 to 1998, but it is worth

noting significant increases in 1987 and 1988.

Table 1:

Increasing Scheme Deductions 1987-1998

|

YEAR

|

SCHEME DEDUCTIONS $M

|

|

1987

|

13

|

|

1988

|

113

|

|

1989

|

73

|

|

1990

|

2

|

|

1991

|

7

|

|

1992

|

54

|

|

1993

|

54

|

|

1994

|

176

|

|

1995

|

288

|

|

1996

|

666

|

|

1997

|

1095

|

|

1998

|

960

|

Source:

ATO Supplementary Submission No. 845B, Attachment 1[1]

1.16

Furthermore, historical evidence shows that both

Governments and the ATO had concerns over claimed deductions associated with

mass marketed schemes.

1.17

A press release from the Federal Treasurer as

far back as the 30th December 1982 shows that the very problem used by the ATO in 1997-1998 to support

retrospective action was a concern then. The press release says:

“On 30 December 1982 I announced that the Commissioner of

Taxation, who has independent statutory responsibility for administration of

the income tax law, had decided to take assessing action under the general

anti-avoidance provisions of Part IVA of the Income Tax Assessment Act to

disallow claims arising from participation in certain film production

arrangements where deductions are substantially leveraged by associated loan

arrangements”(emphasis added).

1.18

Moreover, during the 1980s the media regularly

featured articles on tax effective investments. These articles, as shown below,

clearly demonstrate that knowledge and concern about such activities did exist.

1.19

The Australian,

March 1981:

“Several schemes involve costs related to special loans to

investors which are structured so as to induce them into projects at no real

financial cost to themselves”(emphasis added).

1.20

The Financial Review, December 1984:

“Even the Federal Government implicitly recognises the extent of

the investment distortion caused by high marginal tax rates by two blatant

examples of tax shelters for high marginal tax payers – the film tax

deductibility rort and the licensed management investment companies (MICs)...In

recognition of these factors the previous Government introduced what may have

been seen by some as extremely generous tax concessions so that the industry

could be funded through the tax system and by direct government handouts.”

1.21

Furthermore, in relation to the history of

agribusiness investments in particular, the same article went on to say:

“The combination of tax shelter and capital gain has produced

widespread interest in a variety of primary industry pursuits. The conventional

route is to buy a rundown farm, build it up with tax deductibility investments

over some years, sell it for a capital gain during a good season. There has

been investment in angora goats, avocadoes, guava fruit, mangoes, macadamia

nuts, afforestation, jojoba nuts, the babaco fruit from Ecuador, lychee fruit,

blueberries or the pepino.”

1.22

The National Times, 7th of June 1985 said:

“ PAY TAX OR GROW A FOREST? – very attractive taxation

benefits.”

1.23

Added to that was the 1991 statement by then ATO

Commissioner Boucher, which said in part,

“I would strongly recommend that in order to be assured of their

tax position, investors obtain detailed and comprehensive advice on the full

tax implications from promoters or their own advisers prior to committing

funds.”[2]

1.24

In many cases the financing structures designed

for schemes during the 1980s were exactly the same, and had the same

objectives, as those now subject to retrospective action. That is, they aimed

to limit the investor’s risk, leverage a tax deduction, and by doing so make

the overall investment much more attractive.

1.25

Given the concerns raised by the Federal

Treasurer in 1982, ATO statements and numerous newspaper articles, it is

difficult to accept the ATO argument that it lacked information on or knowledge

of Mass Marketed Schemes and their alleged abusive features when they emerged

during the 1990s.

Effective Signalling

1.26

The ATO maintains that its concerns about

abusive features in schemes were obvious to the market place well prior to the

prolific growth in claimed deductions in the years 1993-1998.

1.27

However, evidence would suggest differently with

the ATO’s position being ambiguous at best. This is highlighted by the ATO

approving thousands of 22ID applications, and issuing a number of Private

Binding Rulings which approved the deductions sought in schemes now subject to

the application of Part IVA. Moreover, a pre ruling consultative document

(PCD9) issued by the ATO in December 1995 and claimed by them to represent a

signal also fails the test of providing clarity and certainty to taxpayers.

1.28

This failing was pointed out in a 1996 internal

ATO report which focused on the very issue of limited recourse financing. The

report stated:

“The PCD does not significantly address the limited recourse

financing issue other than with respect to early termination of the loan and

the application of section 82KL.”

1.29

As stated earlier, the ATO did conduct some

audit activity in the late 1980s- early 1990s. The following list outlines some

of the schemes audited by the ATO and the reasons their deductions were

disallowed.

Scheme

24 – Viticulture / Horticulture Scheme

1987

- Part IVA Application

- Investors were not carrying on a business

- Expenditure by investors was of a capital nature

- Arrangement was a sham

- Non-Recourse Financing

- Round-Robin Transactions

Scheme

25 – Viticulture / Horticulture Scheme

1988

- Part IVA Application

- Round-Robin Transactions

- Non-Recourse Financing

Scheme

21 – Viticulture / Horticulture Scheme

1989

- Part IVA Application

- Taxpayers were not carrying on a business

- Taxpayers were passive investors

- Borrowers borrowed 100% of the funds from an in-house financier

Scheme

28 – Crayfish Breeding

1989

- ATO disallowed deductions claimed

- Financing arrangements were considered artificial flowing in a round-robin between the in-house

finance company, the borrower and the manager.

Scheme

26 – Afforestation Scheme

1992-93

- Scheme had a mixture of full and non-recourse loan arrangements

- Non-Recourse loan element was not allowed

Scheme

22 – Viticulture / Horticulture Scheme

1993-94

- Part IVA Application

- Significant artificial management fee

- Income as a result of round-robin and non-recourse financing

- Whole scheme based on round-robin and non-recourse financing

1.30

Again the question arises that following the

disallowance of deductions in nine out of fourteen schemes on the basis of

non-recourse finance and large upfront fees, why didn’t the ATO issue a tax

ruling? Why did the ATO allow schemes with exactly the same non-recourse

financing and fee elements to continue throughout the 1990s to the extent that

so called non allowable deductions rose to $1.5 billion in 1998/1999? Finally,

why did it take until 1998 before any decisive action was taken?

1.31

Across the board evidence presented to the

Committee suggests that, at best, confusion reigned supreme and, at worst, the

management and application of the tax laws of this country was downright incompetent.

1.32

What is also clear now is there has been no

consistent application of Part IVA, and the obligation on the ATO to provide

certainty and security for taxpayers has not been met in many areas. A

demonstration of such inconsistency arises in the Infrastructure Bonds and Unit

Trusts areas.

Infrastructure Bonds

1.33

During the early 1990s the Federal Government

adopted a number of legislative and policy initiatives through the

establishment of Infrastructure Bonds. Combined with generous legislative based

tax concessions the objective was to facilitate and promote greater investment

in large infrastructure developments. While essentially based on good policy

and sound initiatives, infrastructure investments were viewed as a favourable

way to invest, as the adoption of certain financing arrangements or structures

allowed not only for a leveraged tax deduction but also a limited level of risk

to the investor.

1.34

The structure and financing arrangements of

infrastructure bonds were provided to the Committee by the ATO and illustrated

by Figure 1.[3]

1.35

As Figure 1 shows the financing structures

developed to market infrastructure bonds to retail investors are not

dis-similar to those employed within the mass marketed area. In essence the

retail investor took out a non-recourse loan, which achieved two objectives.

Firstly, the investor could not only limit their overall risk but claim an

immediate tax deduction. Secondly, the loan in many instances would have been

paid out through proceeds often derived after the completion of the project;

for instance, from tollgate revenue on a freeway project.

1.36

Many large organisations were involved in

Infrastructure Bonds including, for example:

The Commonwealth Bank

1.37

The Commonwealth Bank’s ‘Infrastructure

Investment Package for Develop Australia Bonds’ is one such example worthy of

investigation. In their Offering Memorandum dated the 23rd of April

1996 the Commonwealth Bank stated:

“The loan provided by CBA (Commonwealth Bank of Australia) is

non-recourse to the investor”.

1.38

The investment was constructed in such a way as

to provide an investor with:

“an entitlement to a tax deduction for management fees incurred

on the investment and interest on the loan”.[4]

1.39

Furthermore, the Offering Memorandum went on to

say:

“For a cash outlay of $70,048 by 14 June 1996, an investor

should be able to obtain a tax refund of $80,048”.

1.40

The last point is a clear issue of leveraging

which should surely bring into question the ‘dominant purpose’ of any investor.

However, as far as I am aware not one investor in these investments was ever

issued with an amended assessment – similar to the current ATO action – on the

grounds that their dominant purpose was to obtain a tax deduction or that the

loan arrangements were designed to limited the investor’s overall risk.

Legal and General

1.41

Another relevant example is an offering from

Legal and General Financial Services, in relation to the following products:

‘Legal and

General Infrastructure Fund 1996-2’;

‘Legal and

General Infrastructure Fund 1996-3’;

‘Infrastructure

Investment Offer’; and

‘Taxation

Advice – Individual Investors’

1.42

Advice on these products from Price Waterhouse,

dated 27 May 1996, stated:

“The financing facility will be repaid from the redemption

proceeds of the units in the Infrastructure Funds and the expected

non-assessable distribution of $25,000 per unit made to the unit holders. The

financing facility will be non-recourse to the investors.”[5]

1.43

As mentioned previously, the ATO has

consistently argued that in many instances the nature of the financing

arrangements in the current mass marketed area resulted in little if any risk

to the investor and hence warranted the application of Part IVA. However, both

the Commonwealth Bank and Legal and General Infrastructure investments sought

exactly that – to limit the investors exposure to risk through the use of

non-recourse financing. It could also be argued that, in both these cases, high

fees were set in order to leverage a substantial tax benefit for the investor.

1.44

There also appear to be inconsistencies in the

ATO’s treatment of infrastructure bonds relative to mass marketed schemes on

the issue of their underlying commerciality. First Assistant Commissioner Kevin

Fitzpatrick, in response to questions put to him by the Committee in regard to

Infrastructure Borrowings, said:

“Infrastructure borrowings are distinguishable from mass

marketed tax schemes. In the latter, round robin, non-recourse financing

arrangements have the effect that little of the funds find their way into any

productive activity.”[6]

1.45

If, as Mr Fitzpatrick alludes, the main reason

for the ATO applying Part IVA to mass marketed schemes is the fact that money does

not go into ‘productive activity’, why then have commercially successful

schemes which export their products world wide and which pay large amounts of

company tax to the Commonwealth, had all of their investors’ claimed deductions

disallowed under Part IVA?

1.46

It is farcical for Mr Fitzpatrick to promote

such an argument. If it were the case that the ATO assessed the application of

Part IVA on the grounds of commerciality or that funds actually find their way

into productive activity, then surely it would have been better for the ATO to

have ‘sifted the wheat from the chaff’ in regard the mass marketed schemes

sector. Instead, the ATO has issued amended assessments to any investor or scheme

based not on commerciality but on the financing and fee structures.

Macquarie Bank – Geared Equity Investment Portfolio

1.47

Further inconsistencies in ATO action are

evidenced by a number of Macquarie Bank Investment portfolios. Macquarie’s

‘Geared Equity Investment’ is one such example. In the first instance, the

promotional material for the investment clearly shows investors that the

investment portfolio is ‘APPROVED’ by the ATO with a Product Ruling (PR

2000/70).[7]

More importantly though, the promotional material says:

“A Geared Equities Investment from Macquarie is an ideal way to

build wealth over the long term through the share market. Macquarie will lend

your clients 100% of the value of their selected portfolio...Best of all, your

clients don’t need to take any capital risks...Macquarie offers your clients 100%

protection against the risk of losing their loan capital, giving them maximum

peace of mind.” [8]

Macquarie Bank – Apollo Trust

1.48

Macquarie Bank has another investment

highlighting similar anomalies and complexities in the ATO’s administration of

the tax law. The Apollo Trust is an investment which allows investors to access

returns subject to the performance of hedge funds. With the Apollo Trust,

Macquarie offers investors two loan facilities, of which one, a ‘Capital

Protected Loan’:

“fully protects themselves (the investor) against any fall in

the value of their investment capital (provided their units are not redeemed

before maturity).[9]

1.49

Furthermore, in relation to risk specifically,

Macquarie Bank’s promotional material goes on to say:

“The structure of the investment aims to offer you an

opportunity to increase the returns from your investment portfolio, while

reducing your overall portfolio risk”.[10]

Concluding remarks

1.50

In assessing these issues it is understandable

why investors caught up in the mass marketed agribusiness investment fiasco

feel the ‘big end of town’ has gained preferential treatment from the ATO. This

point has further credence when the ATO themselves point out that 97 per cent

of all investors now issued with amended assessments in relation to the Mass

Marketed schemes area – with associated penalties and interest – sought the

advice of a tax agent in making their claims.[11]

Questions relating to what actually constitutes due diligence by the ATO need

to be seriously addressed, particularly given the onus placed on individual tax

payers by a self assessment tax system. With this to one side, the point still

remains that the financing structures used by many of the current scheme designers

have been utilised for over 20 years with only spasmodic and inconsistent

application of Part IVA.

1.51

The reasons for the ATO applying Part IVA are

complex but are summarised in a speech by Second Commissioner Mr Michael

D’Ascenzo to the Taxation Institute of Australia on 22-24 March 2001. He argued

that there are a number of aspects which trigger the application of Part IVA

namely:

- Grossly

excessive/inflated fees;

- The

mechanisms employed to discharge investor liabilities;

- Financing

arrangements;

- Investor

business risk;

- Source

and amount of cash funds applied to the underlying activity;

- Commerciality

of the project; and

- The

financial position of the promoter and promoter related entities.

1.52

Similarly, Mr D'Ascenzo

made the following comment before the Senate Committee hearings on 23 August

2001:

“Again, the existence of non-recourse finance is a factor that

we take into account. We make it very clear that, when we see non-recourse

financing, the level of risk associated with the activity starts to give rise

to whether or not what you are really after is a tax deduction.”[12]

1.53

It is undoubtedly the case that a number of

schemes and investors now having Part IVA applied, entered into non-recourse

financing arrangements. This subsequently leveraged a tax deduction to the

investor and limited their overall financial risk. However, so did a number of

schemes marketed in the mid to early 1980s.

Infrastructure Borrowings and Part IVA

1.54

On the 14th of February 1997 the

Federal Treasurer Peter Costello issued a statement, which said in part:

“ a number of measures [are being introduced] to prevent abuse

of the infrastructure borrowings (IB) taxation concession instituted by the

Labor Government, which if left unchecked would pose a major threat to the

revenue.”

1.55

At the time IBs approved by the Development

Allowance Authority (DAA) had an estimated value in excess of $4 billion

dollars. According to the Treasurer, the DAA had been monitoring applications

and found that:

- schemes being proposed are exploiting the concession for tax

minimisation schemes; and

- these additional taxation benefits are principally being accessed by

financial packagers and high marginal tax rate investors.

1.56

Essentially, a legitimate process designed to

encourage infrastructure development was being leveraged and aggressively

marketed to such an extent that the Treasurer felt legislation had to be

implemented to curb the abuse. The Treasurer alluded to this abuse in the same

Press Release saying that:

“As a result of this transaction (i.e the re-engineering of the

accepted model), for an investment of $36,000, they (the investor) get $85,000

worth of tax deductions.”

1.57

The fact that Part IVA was never applied to

infrastructure investments, despite such evidence of aggressive leveraging,

must seem remarkably unjust to those investors in mass marketed schemes who

have had deductions disallowed and Part IVA penalties applied. This is

particularly so, given that many invested in projects that are still operating

and in many instances making good profits.

1.58

From a legal perspective the abusive

developments of IBs and the associated concerns raised by the Treasurer bring

into question the ‘dominant purpose’ of investors. Did they invest to see

infrastructure projects developed or to gain a tax deduction? This question is

answered by the Development Allowance Authority’s findings that IB schemes were

being exploited for tax minimisation purposes and taken up by high marginal tax

rate investors.

1.59

Lastly, it could be argued that the abusive

concerns in regard to IBs raised by the Treasurer himself in 1997, trigger all

7 points which facilitate the application of Part IVA, as identified by Second

Commissioner Mr Michael D’Ascenzo in his speech to the Taxation Institute in

2001. Why then were the Government and the ATO content – in the case of IBs –

only to implement legislation to curb tax abuse but not address whether Part

IVA applied as it does in the case of mass marketed schemes?

1.60

In fact, First Assistant Commissioner Kevin

Fitzpatrick, in written evidence to the committee on June 15 2001, said that in

one particular IB scheme, Part IVA did apply. He said:

“I am advised that we obtained advice from Senior Counsel in

respect of one [IB] project in which counsel concluded on the facts of that

case that there were reasonable prospects for the operation of Part IVA to some

of the retail investors.”[13]

1.61

To my knowledge, however, the ATO did not apply

Part IVA penalties to any of the retail investors alluded to by Senior ATO

counsel. Furthermore it must be noted that given the sheer size of many

infrastructure projects, one IB scheme alone could involve hundreds of millions

of dollars worth of investment capital. Again why was Part IVA not applied

either to scheme designers or retail investors in this instance? This argument

gains momentum when one considers the fact that investors involved in IBs could

in most instances be considered ‘sophisticated investors’, unlike the great

bulk of investors in the mass marketed schemes.

1.62

In many respects the inconsistencies in

treatment between IBs and mass marketed schemes goes to the heart of the self

assessment tax system and what the ATO constitutes as due diligence.

MMS and Part IVA

1.63

The inconsistencies in applying Part IVA have

engendered a serious public image problem for the ATO, as well as confusion in

the market. For instance, Colin Thomas from Hudson Croft and Thomas Accounting

firm in Sydney argued in evidence to the Committee:

“In my view no tax professional with specialist knowledge in

this area believed that Part IVA would apply to genuine business transactions

where limited recourse or indemnified loans were used to finance the

transactions. This is on the basis that the loans were properly documented and

the funds flowed to evidence the transactions. The existing rulings and tax

cases gave a clear indication.”[14]

1.64

In support of this view Robert K. O’Connor QC

argued in evidence provided to the Committee that:

“In my opinion, the ATO failed to ensure that new laws were

introduced to amend the Tax Act to overcome tax schemes. At law, the Courts had

held that round-robin transactions are valid. Similarly, non-recourse funding

was accepted in Lau’s case (1984) 84 ATC 4929.”[15]

1.65

Other aspects that need to be raised in regard

to the inconsistencies and vagueness of the ATO’s action are the following.

1.66

In October 2001, the Committee asked Assistant

Commissioner Peter Smith why Part IVA was never applied to a plantation timber

company which, in offering investors investment opportunities, clearly

exhibited a round-robin financing structure.

1.67

In answering the Committee’s concerns Mr Smith

said:

“In considering the application in respect of the year ended 30

June 1997, it was evident that the loans involved a round robin arrangement but

due to the size of the fees and the full recourse nature of the loans this was

not considered to be a problem at the time.”[16]

1.68

According to tax ruling TR 2000/8 a round robin

arrangement “includes any mechanisms employed to effect the discharge of

liabilities...”.[17]

Furthermore TR 2000/8 questions the use of round robin arrangements by asking:

“Are mechanisms of this kind commercially explicable and not part of

arrangements to inflate, or artificially create, tax deductions?”[18] In conclusion, the answer

given by Mr Smith raises the question that if the up-front fees had been

higher, or, in the ATO terms, were ‘Grossly Excessive’, would the ATO have

applied Part IVA in regard to this project? The answer to this question is

clearly NO and the following section demonstrates why.

Grossly Excessive Fees

1.69

The ATO has been repeatedly asked by the

Committee to verify what it considers to be grossly excessive in regard to

commercial rates and fees described in TR 2000/8. The Committee has also asked

the ATO to explain how it determines, through Product Rulings, the validity of

claimed tax deductions and, therefore, how it assesses the question of Part

IVA’s application and the investors’ dominant purpose. The Chair of the

Economics Committee asked Senior ATO representatives:

“I would specifically like to know how you determine what are

commercial rates, fees and charges.”[19]

1.70

Mr Bersten (former Deputy Chief Tax Counsel of

the ATO) answered:

“Senator if I can refer you to paragraph 134 of the ruling

itself, it says: A commercially realistic rate is usually fixed by looking at

fees charged by bona fide operators in respect of the actual activity and range

of services to be provided.”[20]

1.71

In addition, Mr Peterson (Assistant Commissioner

for Small Business) pointed to such things as ‘a fair margin’, or ‘what

you would normally expect to find in the market place’ and so forth.[21] However, in discussing the

level of management fees and up-front charges and the associated deductibility

of these fees, Mr Peterson emphasised that the ATO assesses such fees within a ‘fairly

broad band width’.[22]

1.72

This ‘band width’, in regard to vineyard

investments, according to Mr Peterson:

“is probably anywhere like several hundred thousand dollars.”[23]

1.73

In other words, the ATO will allow claimed

deductions for an investment in a vineyard anywhere from the average fee, let’s

say $40,000 to $340,000!

1.74

Of greater concern was Mr Peterson’s

suggested ‘band width’ for an investment in Paulownia plantations. He

argued that the band width acceptable in this area was as narrow as $500 or

$600.[24]

1.75

However, the ATO has issued Product Rulings for

Paulownia plantations with subscriptions ranging up to $52,500 per hectare,

which is clearly outside the band width set by the ATO. This amount would also

seem to fall into the grossly excessive fees category, as it in no way reflects

normal market rates.

1.76

Given that the ATO has, on numerous occasions,

used ‘grossly excessive fees’ as a justification for applying Part IVA, it is

puzzling as to why they have issued Product Rulings for projects, such as

Heritage Paulownia, which appear to have fees which exceed the market norm.

1.77

Moreover, it demonstrates that failings continue

to exist in the ATO when it comes to dealing with mass marketed tax effective

schemes.

1.78

It also highlights the major failings that

existed within the ATO’s risk assessment process in regard to earlier scheme

deductions now the subject of Part IVA action.

Additional Concerns

1.79

Throughout this saga the ATO has sought to lay

the blame squarely at the feet of promoters, advisers, scheme developers and

investors. However, and as previously stated, the evidence simply does not

support that position.

1.80

The ATO and some members of the Committee

promote a view that to allow deductions for investors involved in mass marketed

schemes to stand would be unfair on the rest of the community. There are two

things that need to be said about that view.

1.81

Firstly, the general community were never

offered the opportunity to participate but had they been offered, most would

have probably taken the offer given the approach taken in the promotion of them

and the type of professional people involved in the process.

1.82

The reality is, though, that the great bulk of

the community does not have the level of income necessary to attract these

types of investment offers.

1.83

It is my view that this approach is simplistic

and seeks to avoid the real issue behind the problem.

1.84

The culture of tax professionals and taxpayers

has been drawn more into focus as a result of the ATO’s actions relating to

mass marketed schemes. A number of issues need to be considered in this

context.

1.85

As stated in the main report, the ATO has turned

its attention to the attitudes of the culture of tax professionals.

1.86

In speeches to the community of taxation

professionals, Mr Carmody and other ATO officers have asked that community to

consider its role in maintaining the integrity of the tax system and have asked

for its help in monitoring and controlling the activities of aggressive tax

planners.[25]

1.87

In addition, a speech to the Taxation Institute

of Australia by Assistant Commissioner Michael O’Neill concluded with the

following exhortation:

“If taxation is the price we pay for civilisation, we tax

advisers, lawyers and accountants, each have a key role in advancing our

community. Your advice will assist clients when considering the legal and

financial benefits of investing in year end schemes.”[26]

1.88

Mr Carmody told the Committee that:

“In my view, the community’s tax system would be best protected

by others supporting the tax office in meeting this objective. In particular,

the tax profession, which is at the coalface on a day-to-day basis, could

provide a valuable role in bringing developments to our attention. There are

mixed views on this in the profession, some preferring the view that their only

responsibility is to their client and that this would be compromised by taking

a community responsibility. This view raises for me a number of

responsibility issues that are worthy of considering. In saying that, is it

saying that tax professionals know or knew the schemes were ineffective but,

because the tax office had yet to act, they would recommend our support claims

made for them? Otherwise, why not make them available to us? If so, is there no

responsibility to the community for the integrity of the tax system, even when

they know or expect the arrangements will not pass muster under the law?” (emphasis

added)[27]

1.89

Additionally, Mr Carmody told the Institute of

Chartered Accountants:

“It is one thing to approach an interpretation of the law from

the perspective of advising a client, particularly where the whole objective is

to minimise tax payable. It is another thing to approach the law from the

perspective of a responsibility to the community for the integrity of the law.”[28]

1.90

The statement in this last paragraph is

interesting in that it seems to seek to confuse the responsibility of the tax

professional to their client and an act of breaking the law.

1.91

Under the self-assessment tax system, it is the

responsibility of the tax professional to advise their client of every

deduction to which the client is legally entitled – that after all is what they

are paid for.

1.92

Responsibility to the rest of the community and

the integrity of the law can only be at issue when the tax professional advises

the client to break the law.

1.93

These are clearly two different things and it is

simply not good enough for the ATO to endeavour to muddy the water by mixing

the two together.

1.94

If the Commissioner and the ATO believe that tax

professionals have knowingly advised clients to break the law, then they should

prosecute them or support action by taxpayers for breach of duty against the

tax professionals so involved.

1.95

The self-assessment system also allows for a

reassessment of a taxpayer’s affairs for up to four years in general terms and

up to six years if the ATO deems that Part IVA applies and indefinitely in

cases of fraud. Where the law is clear and concise, these measures should

suffice for the ATO to collect the revenue to which it is entitled.

1.96

Any effort to employ morality as a solution to

the interpretation of tax law is doomed to failure as has been witnessed over

the life of the self-assessment tax system. Two witnesses to the Committee made

important points in this regard.

1.97

Mr Robert O’Connor QC stated:

“If morality had to be taken into account in interpreting the

meaning of the law, whose morals should be applied? The answer to what the law

is would vary and depend on the morals of the particular person giving the

opinion.”[29]

1.98

Mr Richard Gelski of Blake Dawson and Waldron

said:

“...not only is it our obligation to advise on the law as it is –

we can be sued if we do anything else – but if we fail to advise a client that

a transaction can be carried out in a more tax effective manner we can be sued

for negligence by that client.”[30]

1.99

The Committee Report draws on a submission by Mr

Michael de Palo from Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu as contrast to the above

views. In my view, Mr de Palo’s comments are not at odds with these remarks,

but represent another way of stating the same thing.

1.100

Moreover, no number of reviews into the nature

and extent of the public interest responsibility that tax professionals should

adopt for the integrity of the tax system will adequately replace clarity in

the law.

1.101

Clarity in the law is the key solution, and

where clarity does not exist then it should be sought or determined by the

Courts or legislation.

1.102

In the case of tax effective investment

products, the law should be amended to require ATO approval for the products

prior to their public marketing and sale.

1.103

If this had been the case in the past the thousands

of investors now caught in the ATO action would not be in that position and at

least $1.5 billion of tax revenue would not be at risk.

Summary

1.104

As has been highlighted in earlier parts of this

report, abusive tax activity is not a new phenomenon and the ATO has had plenty

of experience in dealing with it.

1.105

What is interesting is how the ATO have dealt

with past problems. In areas such as Unit Trusts and Infrastructure Bonds, the

ATO, Government or both moved to end abusive activities but in both cases they

did it prospectively, not retrospectively.

1.106

When this was raised with the ATO, they argued

there were important differences between Unit Trusts and Infrastructure Bonds

and Mass Marketed Schemes.

1.107

The ATO stated that in relation to afforestation

schemes, the ATO public position was that deductions would not be allowable if

Part IVA applied, but that it had not made any comparable statement in respect

of Unit Trusts and as such a clear signal existed in one area and not in the

other.

1.108

The ATO also stated that the prospective

decision on Unit Trusts was based on the arrangements being implemented in line

with the information provided to the ATO on which it based its advanced

opinions.

1.109

In contrast, the ATO allege that in the case of

Private Binding Rulings for Mass Marketed Schemes, the promoters neither

provided all of the facts nor implemented the arrangements according to the

facts presented.

1.110

However, the ATO never produced any evidence to

support these claims and it was remiss of myself and the Committee not to have

pursued this matter further as it is fundamental to the equitable application

of our tax laws.

1.111

Moreover even without greater scrutiny, the ATO

position is found wanting. For example, in the case of one Private Binding

Ruling issued to an investor in Main Camp Tea Tree Oil, the investor provided

what can only be considered as all relevant information, including information

that the investments involved limited/non-recourse financing. Indeed, the

applicant asked the ATO if they needed any further information to which they

responded in the negative.

1.112

Moreover, if the ATO felt that it didn’t have

all the relevant information, why didn’t it ask for it?

1.113

Why didn’t the ATO – given their alleged concern

about financing arrangements - specifically ask about them?

1.114

To try and hide behind a position that a clear

signal existed in one area over another simply because you have mentioned Part

IVA does not hold water.

1.115

There is no requirement for the mentioning of

Part IVA for it to apply, indeed Part IVA is there for the purpose of dealing

with breaches of the tax law, the “general anti-avoidance provision”.

1.116

In addition, I doubt the ATO ever investigated

all of the arrangements associated with Unit Trusts to determine whether or not

they were implemented exactly in accordance with the advance opinions issued.

1.117

As is cited earlier in this report on

Infrastructure Bonds, the government took prospective action in bringing to an

end the rorts occurring in that area, which given the nature of the abuse as

highlighted by Treasurer Costello, makes the ATO action in the Mass Marketed

area even more questionable. In my view, it smacks of the old ‘Animal Farm’

theory.

Concluding Remarks

1.118

There is no doubt that many features of the Mass

Marketed Tax Effective Schemes were tax abusive and needed to be stopped.

However there is also no doubt that such activities developed and flourished as

a result of identical or similar practices in other areas of the market place.

Add to that a systemic failure by the Tax Office to clarify their position ‘at

law’ and therefore their application of the law, and you have a recipe for

disaster which is what happened.

1.119

One could be forgiven for concluding that the

ATO’s action in the Mass Marketed area had more to do with the Government’s

February 1997 decision in regard to Infrastructure Bonds than anything else! It

is also a fact that – from a historical perspective - where the ATO has not

formulated a view on the application of the law, or where the ATO or Government

have changed their view in regard to particular taxpayer action, they have

consistently acted prospectively!

1.120

The ATO and its Commissioners have an obligation

under the Taxpayers Charter to treat all taxpayers equally and equitably, and

it is my view that this obligation must be upheld at all cost. It is also my

considered view that the ATO is seeking to treat one group of taxpayers (the

Mass Marketed group) in an entirely different fashion to those involved in the

same or similar activities in other areas.

1.121

Consequently the ATO’s action should be

condemned and viewed as unjust, and the Government should request the ATO to

refrain from taking any further action against these taxpayers. The ATO’s

action goes to the very heart of the integrity of the tax system and if allowed

to continue, will only increase the distrust in both the tax system and ATO now

so evidently clear.

The Managed Investment Industry – Product

Rulings

Protecting the Commonwealth Revenue

1.122

Over the past 22 years threats to the tax

revenue have operated in various forms, with the use of certain financing

structures and high management and lease fees perhaps the most prominent

examples. It is now clear that high wealth individuals have consistently been

able to gain large net cash benefits through a range of varied investments by leveraging

tax deductions through the use of limited and non-recourse financing.

1.123

Such activities occurred in the issuing of

Infrastructure Bonds (IBs), Unit Trusts as well as Mass Marketed Agribusiness

and Franchise schemes. Of most interest is the fact that in 1997 the Government

moved to block abuses in the IB area where investors were leveraging large tax

benefits and in some instances gaining a net cash benefit after tax. Similarly,

in 1998 the ATO moved to end exactly the same problems evident in the MMS area.

It is clear that limited and non-recourse financing and excessively high

management and lease fees were the more common tools used for leveraging large

tax deductions.

1.124

In June 1998 the ATO introduced the Product

Ruling system which was designed to better protect the revenue base while

providing greater certainty for taxpayers. Whether this has been achieved is

highly questionable and is an issue now canvassed by this report.

Commissions

1.125

Even though the Corporations Act clearly

stipulates that commissions must be disclosed this area of corporate governance

still exhibits many transparency related concerns. The Australian Securities

and Investment Commission (ASIC) told the Committee that out of 91 prospectus

documents investigated by ASIC:

“30%

did not disclose the commissions payable or the percentage of commission

payable.”[31]

1.126

A further illustration of this is found in a

2000-2001 Prospectus for one of Australia’s largest plantation timber companies

where the percentage or level of commissions paid by the company to associated

entities is unclear. The prospectus says:

“In addition, from their own funds, the responsible entity or

other companies within the same group of companies might pay additional fees to

licensed dealers in securities who have provided particular assistance of an

administrative or promotional nature in connection with the projects.”[32]

1.127

It is difficult to sustain a legal argument that

this vagueness over fees breaches Section 849 of the Corporations Act. However,

it does go to the heart of mandatory disclosure and the right of an investor to

know exactly how the responsible entity spends or uses their money. The

investor should be entitled to know exactly how much the company is paying in

commissions to outside entities. Is it 10% or 25% in total? Only then can an

investor make an informed judgement as to how much of their money is actually

going into the project.

Recommendation

1.128

Legislative changes need to be implemented which

force responsible entities and directors etc to clearly disclose the total

amount of commissions payable. It is clear that in a number of circumstances

the softer parts of the law are exploited by promoters to hide the true extent

of fees and commissions paid.

Large Up front Fees

1.129

Concerns with disclosure and transparency are

similarly evident with the use of large up-front management and lease fees by

companies. In the first instance, while classified as ‘Management and Lease

fees’, close scrutiny shows that in reality only a very small proportion of the

up-front fee exhibits a management and lease fee component. In fact, a

significant proportion of the fee – sometimes in excess of 40-50% – is used by

the company to purchase land or other assets to establish the project. This is

rarely disclosed to investors and raises a number of serious concerns.

1.130

In regard to blue gum plantations, some

plantation companies charge investors an up-front fee in excess of over $9,090

per hectare. Credible research from Government agencies such as the Department

of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) in Western Australia, and academic

departments such as ANU Forestry, show that it should cost no more than about

$3,000 (maximum) to establish one hectare of blue gums on leased land over a

10-12 year rotation period.[33]

1.131

Allowing large up-front management and lease

fees to be charged poses a number of problems. In the first instance, there is

significant drain on the Commonwealth revenue by allowing scheme promoters to

classify the funds contributed by investors as management and lease fees, when

in most instances nearly half of the money is used to purchase land as a

capital item. Consequently scheme managers use someone else’s money in the

guise of management and lease fees, to buy land which they can sell and take a

profit.

1.132

In essence the whole arrangement is an

inefficient mechanism by which the Commonwealth helps facilitate investment and

therefore is not dissimilar to the concerns and comments made by the Treasurer

in 1997 when putting a stop to the abuses found with IBs. On this point the

Treasurer said:

“Now,

I want to make it clear that the Government is not being critical in any sense

of the projects. The vice, however, with infrastructure borrowings is that the

taxpayer is not getting value. This is a very expensive way of getting money

into those projects. It’s tax expensive because instead of, as was the original

plan, the borrower foregoing their right to have a tax deduction and the tax

foregone by the borrower equalling the tax benefit received by the lender on

some kind of symmetric one-to-one ratio, you’re getting in these sorts of

examples ratios of one-to-seven or higher. That is, the benefit to high

marginal taxpayers in terms of their ability to save themselves tax is extreme

multiples of the tax rights foregone by the borrowers. What that means is that

this is not an effective scheme for taxpayers.” [34]

1.133

The concern with this arrangement should, in

theory, be picked up by the Managed Investments Act. However, scheme promoters

are able to smartly side step the legislative provisions. Under the MIA Act any

land bought by the scheme or through investments by investors in the scheme

should be classified as ‘Scheme Property’. However, scheme managers (ie, the

responsible entity) are able to circumvent Section 601 FC, Duties of responsible

entity, of the MIA Act. Section 601 FC states:

- In exercising its powers and carrying out its

duties, the responsible entity of a registered scheme must:

- ensure that scheme property is:

- clearly identified as scheme

property; and

- held separately from property of

the responsible entity and property of any other scheme.

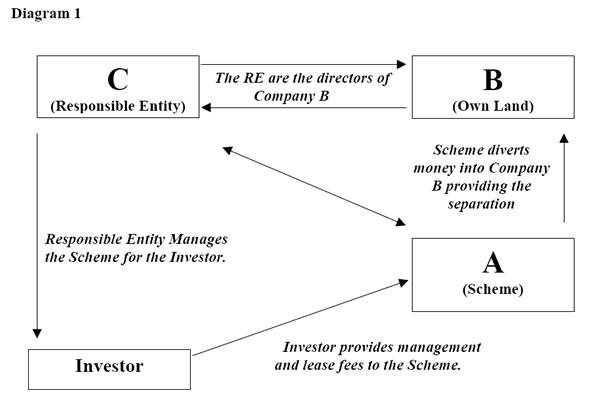

Diagram 1

1.134

As per diagram 1, to circumvent Section 601 FC

the responsible entity – or directors of the parent company running the scheme

– divert investor funds into a sister company, of which the Directors of the

parent company are themselves the principal shareholders. The directors then

use these funds to buy land to establish the project. While technically the

company complies with the law and there is no scheme property, the ethics of

the transaction are questionable because of the lack of transparency. In most

instances, it is nearly impossible to find acknowledgment of this process in

any prospectus. Investors are therefore unlikely to be aware that up to 50% of

their funds are going into the purchase of land which they do not own or have

any control over. Consequently, the tax system is essentially paying for scheme

managers to accumulate land assets which only they own.

1.135

The ability of scheme managers to circumvent

legal obligations in this manner raises concerns about the adequacy of the

rules for disclosing what a company does and does not do with investors’ money.

ASIC Policy Statement 56 ‘Prospectuses’ in section 56.119 says:

“Subsection 1021(6) specifies a more substantive information

requirement, that is, the prospectus must disclose the interests of directors,

proposed directors and experts in the promotion of, and the property to be

acquired by, the corporation (s1021 (6)).”

1.136

Furthermore, ASIC general disclosure

requirements state that, except when s1022AA applies, a prospectus must contain

all information investors and their professional advisers would reasonably

require and reasonably expect to find in the prospectus. It is obvious that

investors would ‘reasonably’ expect to know how every dollar of their

investment monies is spent.

Registration and Review of Prospectuses

1.137

ASIC in evidence to the Committee said:

“We have power to review prospectuses but, practically, we do

not have the resources to look at all of them. The Government specifically

removed the requirement to register a prospectus so our ability to stop

prospectuses at the registration stage was removed.” [35]

1.138

Currently ASIC vet only a small proportion of

all prospectuses lodged with them and assess prospectuses only in regard to

their compliance with the Corporations Law. ASIC therefore do not verify the

forecasts and projections contained in prospectus documents or the validity of

expert opinions.

1.139

This is a serious shortcoming which will

inevitably get worse once the reforms initiated under the Financial Services

Reform Act are implemented in March 2002. Under the new laws the responsible

entity of a managed investment scheme will not be required to lodge a

prospectus with ASIC. Instead the onus to comply with the law will rest solely

with the responsible entity. This is a serious problem, especially given that

under the current regime ASIC say:

“ASIC found that some RE’s had inadequate compliance monitoring

and reporting systems that, in some cases, led to breaches of the law by the

RE. Our findings demonstrated a lack of active implementation of compliance

arrangements and a lack of strong management commitment to implementing them in

some organisations.”[36]

1.140

In analysing the FSR Act it is clear that the

legislative changes were adopted to appease large financial institutions with

diverse investment portfolios. However, the legislation has failed to clear up

a number of anomalies at the lower end of the investment market that rely on

issuing prospectus documents.

1.141

It is clear from ASIC statements that they

simply do not have the resources to adequately monitor this sector and

therefore provide investors with adequate protection. Without a significant

increase in resources it can be predicted that the problems currently

experienced by the regulator will get worse.

Recommendation

1.142

It is therefore recommended that the law be

changed, or the implementation of the Financial Services Reform Act be delayed

for a further 2 years until a review of compliance is conducted.

‘Experts’

1.143

Another anomaly which must be addressed is the

use of expert opinions in prospectus or offer documents. Investors

understandably place a great deal of trust in not only the financial forecasts

and projections included in a prospectus but also in the expert reports

contained in them. However as the Business Review Weekly reported on

August 30 2001:

“Few investors would suspect, for example, that some promoters

of investment products shop around for sympathetic professional opinions for

their prospectuses.” [37]

1.144

ASIC Practice Note 55, ‘Prospectuses – citing

experts and statement of interests’, sets out clear guidelines on the use of

expert opinions in prospectuses.

1.145

Practice Note 55 states that the expert is

accountable for their advice cited in a prospectus,[38] and that the expert must give

their written consent for their opinion to be cited.[39] If such consent is withheld

but the expert opinion is nevertheless cited in the prospectus, then the directors

are liable to indemnify the expert.[40]

1.146

While Practice Note 55 is fairly extensive, a

number of serious concerns remain. First, the Practice Note does not stop

promoters from shopping around for a favourable opinion. Second, ASIC do not at

any stage verify whether the expert cited in a prospectus is in fact an

‘expert’. Consequently, ASIC say:

“If a prospectus mentions a person’s view on a matter, the ASC

will normally take the prospectus as holding the person out to be an expert on

that matter.” [41]

1.147

This raises serious questions as to the validity

of claims of expertise. Who is an expert and how qualified are they to make

judgements?

1.148

In the case of plantation forestry, this is a

serious problem, particularly as nearly all ‘experts’ will endorse the Mean Annual

Increment (MAI) growth rates reported in prospectuses. The MAI’s underpin the

forecasted returns to investors. The concern is that most plantation companies

forecast returns to investors on an average MAI of 30/c.m/ha/yr. This is

extremely misleading, firstly, because an average MAI of 30 means that some of

the trees will grow at a MAI of around 40. These figures are inflated. Sound

evidence shows that in even the best growing conditions an average MAI of

around 20-22 is achievable but very unlikely.[42]

If the lower figure were used, the forecasted return to investors would be

seriously diminished. However, so-called experts still sign off on average

MAI’s of 30. This is why some tax specialists argue that:

“...independent expert opinions are so heavily qualified that

their conclusions are almost meaningless.”[43]

1.149

In short, reliable evidence demonstrates the

misleading nature of many projections in prospectuses, which in turn casts into

doubt the credibility of ‘expert opinions’ used to support the claims of such

prospectuses.

Recommendations

1.150

Like most aspects of the managed investment

industry the area of expert opinion lacks integrity. It would seem that often

experts are ‘friends’ or close business associates of the RE and therefore paid

to give a favourable opinion. The entire system requires stronger measures to

improve independence and objectivity. It is therefore recommended that ASIC

consider either establishing a board of experts or a system for registering

experts. Under this regime it should be mandatory for experts to disclose any

conflict of interest in relation to the schemes for which they provide

opinions. For investors these measures would provide a greater degree of

certainty that the expert is indeed an expert. Currently no one including ASIC

is in a position to assess claims to expertise.

1.151

It is further recommended that ASIC be given

statutory responsibility for issuing expert opinions for all Mass Marketed

investment schemes. The onus will be on the scheme promoters, designers and/or

managers to provide ASIC with the investment proposal so that the proposal can

be independently and ‘expertly’ assessed. An ASIC report on the proposal should

include advice on general market conditions, the going market rates for

establishment of the project, the yields and returns that could be

realistically expected and the projections for the future of the industry.

Furthermore, the ASIC report must be included in the final prospectus, or any

other marketing information related to the project, and a copy must be provided

to the ATO.

Product Rulings and Grossly Excessive Fees

1.152

A further concern is that the PR system is

unable to support credible business investments and at the same time protect

Commonwealth revenue. This is because the process by which the ATO determine

whether management and lease fees are ‘Grossly Excessive’ is seriously flawed.

As a consequence the PR system is unable to prevent schemes which are extremely

expensive and which exhibit unrealistic or un-commercial fees and charges from

going ahead. Investors are then afforded tax deductibility for outgoings and

the Commonwealth props up overly expensive schemes.

1.153

It is not the role of the ATO to determine how

much a company can charge or how much an investor should outlay. Nevertheless,

the ATO does have a responsibility to clearly assess whether scheme managers

are charging fees that are, as the then Deputy Chief Tax Counsel Mr Bersten

said in evidence, ‘commercially realistic rates’.[44] The Part IVA anti-avoidance

provisions require the ATO to examine the level of fees in arrangements with

tax benefits. Grossly excessive fees are one of the eight factors that can

trigger the application of Part IVA.[45]

The problem is, however, that while the ATO cites grossly excessive fees as the

reason for applying Part IVA in some cases, it continues in other cases to

provide product rulings for schemes with management and lease fees far above

the market norm.

Product Rulings and Business

1.154

The ATO has argued consistently that the PR

process is primarily concerned with protecting investors not facilitating the

needs of business. At the outset this position is accepted in that investors

need greater protection and certainty. However, the fact that the PR process is

not overly responsive to business requirements is of concern.

1.155

There are delays in processing PR applications

which vary from 28 days to 2 years. Such inconsistencies pose considerable

problems and frustration for businesses particularly those involved in the

agri-business sector which rely heavily on planting regimes aligned to seasonal

conditions.

1.156

The delays experienced by business from the

application date of a PR to finalisation are exacerbated by the structure of PR

drafting. The best way to explain this is to provide an example of what can

occur.

PR Process Example – the 28 day clock

Example 1

- Promoters/Managers apply for a PR;

- Forward PR

application to Melbourne ATO office;

- Application is

assessed;

- Further

information may be sought;

- Further

assessment;

- Melbourne office

forwards the application to Perth for peer review;

- Further

information may be sought;

- Perth office

sends the application back to Melbourne for changes;

- Peer reviewer may well

require to view changes before the Melbourne office sends the application to

Brisbane for review by the Centre for Excellence;

- The Centre for

Excellence may require more information and changes to be made;

- The Brisbane office

then sends the application back to Melbourne with accompanying recommendations;

- Melbourne then send it

to the applicant for their approval;

- For the PR to be gazetted in Canberra on a Wednesday the Melbourne office will

have to have the application finalised in Melbourne the previous Tuesday.

Example 2

- Scheme has

already been granted 2 PRs for the previous 2 years;

- Manager applies

for an additional but identical PRr to expand the existing operation;

- Applicant has to go through the entire process again as listed in

example 1.

1.157

The above two examples actually occurred to a

medium to large agri-business company during the years 1999, 2000 and 2001. It

is clear therefore that the PR ‘sausage machine’ is antiquated and very

inefficient. In addition to delays is processing applications, the PR system

suffers from serious communication breakdowns often experienced between the ATO

and PR applicants, chronic staff shortages – our estimate is that the PR system

has no more than 30 ATO staff working on PRs nationally. Serious questions need

to be asked about the PR system and it’s ability to respond to Australian

business.

Time taken to produce PRs

1.158

The systemic inconsistencies and time delays

experienced between the initial application date and the finalisation of the

requested PR are unacceptable. As a consequence the entire PR system lacks

credibility with the business sector because on many occasions the ATO give

verbal guarantees to finish a PR within a set period of time but nearly always

fail to deliver. This is exacerbated by the ATO consistently requesting new

information from the PR applicant. On many occasions the applicant would

question the ATO as to why they failed to ask for the information at the

outset.

Structural concerns - The need to centralise the PR Process

1.159

The argument for centralising the PR system

must, as a consequence, be seriously addressed. One solution would be to have

two main offices, one in either Sydney or Melbourne and one in Perth dealing

specifically with PRs. While specific locations can be negotiated and discussed

at a later stage, the main objective should be to improve the integrity of the PR

process for investors, with a greater commitment to designing a system which

better responds to the needs of modern business.

Concluding comments

1.160

The constant delays evident in the PR process

cause a number of problems. It unnecessarily constrains business and inhibits

investment to the extent that investors – particularly international investors

– may view the consistent delays as evidence of non-compliance with tax laws by

scheme managers, rather than a sloppy bureaucratic process. As a consequence, schemes

often lose investment capital and investor confidence.

1.161

There is no reason why the PR process cannot be

redesigned to better facilitate business while continuing to provide investors

with excellent protection. If the ATO addresses the time delays, communication

and resourcing issues, there is no reason why the PR process could not be one

of the best in the world in providing investors with protection and business

with certainty.

Recommendations

1.162

It is recommended that the ATO adopt a similar

time frame or commerciality approach with PRs as they have done with Private

Rulings. The ATO gives an undertaking to provide a Private Ruling within 28

days from the application date. With PRs 28 days is simply not long enough.

However, the ATO could realistically in most cases draft a PR from application

to finalisation within a period of 3 to 4 months. The time period in essence

however is irrelevant. What is relevant to business is that they are given some

sense of certainty. As it stands they are inundated throughout the process with

requests for more information and have absolutely no idea at all when the PR

will be finalised. For most businesses it wouldn’t matter if each PR took 6-8

months as long as they knew. Only then can they forward plan their PR application

according to the investment market and seasonal planting regimes.

1.163

Furthermore, it is recommended that the ATO be

given a 28 day period starting from the application date to request further

relevant information. As it stands the ATO consistently return to scheme

managers with requests for more information some 6 months into the process.

Most find this terribly frustrating particularly when they apply for back to

back PRs for exactly the same investment project.

1.164

It is recommended that it be an offence, under

the Trade Practices Act, to market and sell an investment product involving

tax benefits without first obtaining a Product Ruling from the ATO.

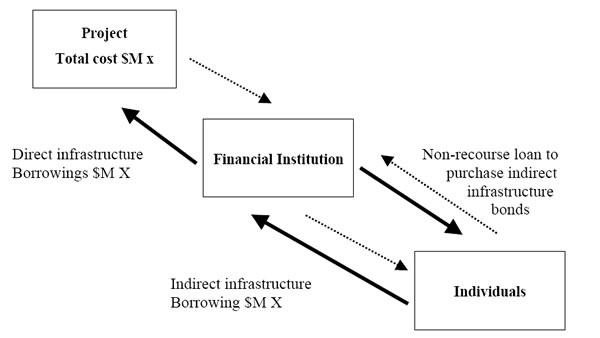

1.165

It is recommended that the ATO disallow any part

of a claimed deduction which relates to the purchase of a capital asset i.e.

land – irrespective of whether that land is purchased for the investor or

another party.

Senator

Shayne Murphy

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page