Chapter 25

ASIC's responsibilities and funding: problems with the current framework

and suggested changes

25.1

This chapter considers two issues fundamental to ASIC's performance as

a regulator: its functions and responsibilities and the resources available for

it

to perform these tasks. Successive governments have given additional

responsibilities to ASIC at various times since it was established. In recent

years there has been a marked increase in the functions ASIC has acquired.[1]

This chapter considers the implications of this and, in light of the issues

raised in previous chapters, the extent to which ASIC's growing list of

functions and responsibilities has affected the agency's performance.

25.2

When considering the responsibilities given to ASIC, it is helpful,

indeed necessary, to examine the resources given to ASIC to perform these

tasks. Accordingly, this chapter also considers the amount of funding ASIC

receives and whether the mechanism in place for funding ASIC should be changed.

Is ASIC overburdened and underfunded?

25.3

There is clearly a correlation between the list of responsibilities ASIC

has, the funding it receives and the outcomes it can achieve. ASIC's submission

contained

the following statement on this relationship:

What we are able to achieve also depends on our level of

funding. Ensuring ASIC has adequate resources affects the strength and

integrity of the financial system and the confidence of investors.

ASIC can only achieve what it is resourced to do. Funding

levels should be set by reference to Government and community expectations of

what ASIC should deliver and, as a result, what level of resilience they want

in the financial system.[2]

25.4

Figure 25.1 outlines ASIC's operating revenue, expenses and staff

numbers since the 2000–01 financial year. Between 2000–01 and 2012–13, ASIC

produced an operating surplus for eleven of the 13 financial years, averaging a

$16.7 million surplus each year.

Figure 25.1: ASIC's operating revenue, expenses and

staff levels,

2000–01 to 2012–13

Source:

Figures for operating revenue and expenses taken from research prepared by the

Parliamentary Library, based on cash flow statements contained in ASIC's annual

reports, various years. Figures for staff levels are taken from ASIC's annual

reports, various years.

Note: Total operating revenue includes

appropriation revenue and other cash received.

25.5

A 2012 report prepared by staff of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)

argued that ASIC 'has rightfully earned its reputation as an effective and

credible enforcer of market regulation, but would benefit from increased

resources and budgetary flexibility'. The IMF staff argued that:

...ASIC is hampered in its ability to fully carry out proactive

supervision because of the lack of budgetary resources. A significant amount of

ASIC's funding is non-core funding earmarked for specific projects, and the

share of non-core funding has been increasing in the last few years. To

supervise a large number of financial services licensees, ASIC uses desk-top,

rather than on-site, reviews for initial risk-based assessments, reflecting in

part its resource constraints. In determining the target and intensity of its

supervisory actions, ASIC relies heavily on its initial risk-based assessments,

self-reporting of breaches of regulatory requirements and third party

notifications. It is important that ASIC be given more resources and

flexibility over its operational budget.[3]

25.6

Many individuals and organisations agreed that ASIC is currently

underfunded. A view also frequently expressed was that ASIC's expanded

regulatory remit had negatively affected ASIC's performance. This was either as

a logical consequence of ASIC having a longer and more diverse list of

responsibilities,

or because the additional funding provided to supplement specific new responsibilities

has been insufficient. The following extracts from the evidence taken by the

committee illustrate some of the concerns:

In recent years, two trends regarding ASIC have emerged.

Firstly, ASIC has been given increasing responsibility for important areas of

corporate and financial regulation, including stock market regulation,

financial services licensing, consumer protection in financial services,

business names registration and credit regulation. These matters add to ASIC's

already full regulatory brief covering general corporate regulation and

administrative matters (document lodgments, searches and maintenance of

registers). During this time while ASIC's funding has increased, much of the

funding has been tied to particular projects (such as key investigations into

HIH and other high profile matters), and the numbers of staff working at ASIC

has only increased from 1221 in 2000 to 1738 in 2012 (according to ASIC's

Annual Reports). The increases in funding and staffing are wholly inadequate to

account for exponential increase in ASIC's responsibilities.[4]

* * *

...the increase in ASIC's mandate over the last decade has not

been matched by financial appropriations and has stretched its personnel.[5]

* * *

...the constant accrual of functions and services by ASIC has

played some part in reducing the ability of ASIC to devote resources to its

legislative, surveillance and investigative responsibilities.[6]

* * *

Our sense is that the problem ASIC has is complexity of

legislation, huge areas of responsibility and resources that are too limited.

It is not a lack of powers, it is a lack of resources, really, and the

practical ability to make things happen.[7]

* * *

In our view, any deficiencies in ASIC's performance and

effectiveness are more likely to be caused by a lack of adequate funding and resources

to allow ASIC to fulfil its role as a corporate regulator. Being well-funded

and resourced is essential for a regulator to be able to effectively use its

powers and discharge its duties. Relevantly, being adequately resourced allows

a regulator to be more pro-active and therefore maximise the chances of ASIC

being able to properly enforce existing legislation. Company Directors has long

called for and supported moves to provide appropriate funding to ASIC and other

regulators to meet the increasing demands that they face, and we continue to

believe that this is the best way to increase ASIC's performance as a

regulator.

This lack of funding is likely, at least in part, to be due

to the fact that ASIC's role as a regulator has been increased significantly

over time and its resources have been stretched as a result. In addition to

increasing the existing funding and resources of ASIC, going forward ASIC's

roles should only be added to or extended where there is also a commensurate

increase in ASIC's funding and resources.[8]

* * *

The finance world is increasingly complicated with emerging

risks and challenges. It is essential that ASIC is adequately funded and

resourced to carry out its duties. We would not support any proposals to cut

ASIC's funding.[9]

25.7

Members of the public that had dealt with ASIC also called for ASIC

to receive more funding:

ASIC needs more funding to go after criminals and credit

providers. ASIC should have enough funding that it can anticipate rorts and

take steps to protect people...There is a perception in the community that ASIC

is reluctant to take a stand possibly because of lack of funding.[10]

25.8

Others were less sure. Levitt Robinson Solicitors argued that 'ASIC's

failures cannot be blamed on budgetary constraints, given ASIC's apparent

profligacy in the deployment of public money spent on, or in outsourcing legal

services'.[11]

CPA Australia noted that ASIC is possibly overworked, but it considered

other problems with ASIC's approach were more significant:

I think there has been a lot of commentary by ASIC to say

that they are very stretched with their resources and there is more to do.

There may be an element of truth in that argument. I think the bigger issue is

that their sense of priority needs to be revisited.[12]

25.9

The Institute of Chartered Accountants Australia (ICAA) noted that all

organisations face financial pressure and need to ensure they use the resources

they have as efficiently as possible. The ICAA argued that ASIC is currently

undertaking work which 'generally has very little effect but consumes quite a

lot of resources'.[13]

On this issue, the Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU) acknowledged that

every organisation needs to focus on and review whether it is undertaking

activities in the most efficient way. However, the CPSU argued:

...if you are not actually reinvesting in the work that is

needed to be done, and having that investment being made then you are likely to

see the services slip. And I think we sometimes confuse at the moment

conversations about productivity and effectiveness with cuts.[14]

25.10

It is evident that funding issues are not just relevant to ASIC; rather

they are something that all regulators encounter. The former chairman of the

Trade Practices Commission, the predecessor to the ACCC, argued that there 'is

a fundamental flaw in the way in which our regulators are funded':

Having acted as chairman of the Trade Practices Commission

(TPC)...I can say with complete confidence that the level and nature of funding

provided to the TPC at the time to conduct its various activities was well

below what was needed to properly and adequately undertake its tasks. This was

certainly the case in the context of community and media (and some

politicians') expectations of the role of the regulator. The apparent

unwillingness of the TPC to undertake certain investigations or to pursue

certain court actions was often misunderstood, because the critics did not

appreciate the problems that the regulator faced due to its inadequate and

restricted use of its funding.[15]

25.11

Professor Baxt added that regulators also have 'inadequate' resources to

bring cases that challenge well-resourced defendants that 'usually enjoy deep

pockets and are not burdened by significant restrictions in the way in which

they operate in defending the relevant matter'.[16]

25.12

Whether ASIC has sufficient resources to adequately supervise the

entities

it regulates can also be considered by reviewing the number of staff ASIC

allocates to each group of the regulated population. As noted in Chapter 4, ASIC

publishes figures on the number of staff members allocated to each of its

stakeholder teams, the number of regulated entities they oversee and the number

of years it would theoretically take to conduct surveillance on every regulated

entity. These figures highlight the challenges ASIC faces in fulfilling its

regulatory responsibilities with its current resources. For example, ASIC has

29 staff members that oversee 3,394 AFS licensees authorised to provide

personal advice as well as 1,395 AFS licensees authorised

to provide general advice. Approximately 65 staff members oversee: 173

authorised deposit-taking institutions; 141 insurers; 641 licensed

non-cash payment facility providers; 13 trustee companies; and 5,688 non-ADI

credit licensees with 28,201 credit representatives. These figures were

outlined in full in Chapter 4 (refer to Table 4.1).

25.13

However, striking figures on supervision coverage and an imbalance

between the regulator's financial resources and those of the large firms it

regulates are not unique to ASIC. For example, in recent fiscal year budget

requests to the United States Congress, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

has given the following bleak assessments of its resources and capacities:

...during the past decade, trading volume in the equity markets

has more than doubled, as have assets under management by investment advisers,

with these trends likely to continue for the foreseeable future. A number of

financial firms spend many times more each year on their technology budgets

alone than the SEC spends annually on all its operations. Similarly, SEC

enforcement teams bring cases against firms that spend more on lawyers' fees

than the agency's annual operating budget.[17]

* * *

Currently, the average transaction volume cleared and settled

by the seven active registered clearing agencies is approximately $6.6 trillion

a day. Yet the SEC only has approximately sixteen examiners devoted to them,

with limited on-site presence in only three of the seven.[18]

* * *

Seven years ago, the SEC's funding was sufficient to provide

nineteen examiners for each trillion dollars in investment adviser assets under

management. Today, that figure stands at ten examiners per trillion dollars.[19]

How do ASIC's responsibilities compare with foreign regulators?

25.14

The breadth of responsibilities entrusted to ASIC compared to regulators

in other jurisdictions was noted by witnesses and used to argue that a review

of ASIC's responsibilities was warranted:

At the moment ASIC has an incredibly broad remit in

comparison to most securities regulators globally. If there was that reduction

in supervisory capacity or its responsibilities perhaps it would allow it to

focus more specifically on some of the issues which concern so many of the

people who made submissions to the inquiry and the members of this committee.[20]

25.15

Even a cursory comparison of Australia's framework of regulators and those

of other key jurisdictions indicates that the breadth of ASIC's

responsibilities is significantly greater than those of its foreign

counterparts. In the UK, for example, ASIC's securities and markets regulation

functions are undertaken by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The FCA also

has responsibility for market supervision and governance (through the UK

Listing Authority, a division of the FCA). The FCA also is tasked with

financial products and services regulation and credit and financial services

licensing. However, the FCA does not have responsibility for matters relating

to the corporations law generally, such enforcing directors' duties or

regulating auditors and insolvency practitioners. Company registration is

performed by Companies House, an executive agency of the Department for

Business, Innovation and Skills.

25.16

In the US, ASIC's securities and markets regulatory counterpart is the SEC,

with some functions also performed by the Federal Commodity Futures Trading

Commission (CFTC) and state authorities. However, the Consumer Financial

Protection Bureau (CFPB) is tasked with financial products and services

regulation, and credit and financial services licensing is undertaken by state

authorities.

The regulation of auditors is carried out by the Public Company Accounting

Oversight Board (PCAOB), although this is overseen by the SEC. Reflecting the chapter

11 bankruptcy and reorganisation system in place in the US, corporate

insolvency is dealt with by specialist bankruptcy courts with an office in the

Department of Justice

(the US Trustee Program) responsible for overseeing the administration of

bankruptcy cases.

25.17

In Canada, provincial and territorial regulators are responsible for securities

and markets regulation and market supervision. The Financial Consumer Agency of

Canada (FCAC) supervises financial institutions' compliance with consumer

protection obligations and promotes increased financial literacy. Financial

advice is regulated by provincial and territorial agencies. The federal

registration of companies is administered by Corporations Canada with

provincial agencies registering other companies. The Canadian Public

Accountability Board deals with auditors.

Should ASIC lose some of its functions?

25.18

Following on from the previous discussion, this section examines the

evidence received by the committee that questioned the wisdom of one agency

being given numerous important regulatory and law enforcement functions as well

as other administrative responsibilities. During the course of the inquiry, various

possible changes that could be considered were suggested or noted by

stakeholders.

These options, which are discussed in the following paragraphs, include:

-

transferring ASIC's corporate and business name registry

functions to another government agency, or privatising these functions;

-

splitting ASIC into smaller regulators along the lines of its

broad business areas; and

-

transferring responsibility for consumer protection to the ACCC

or creating a new consumer protection agency.

Corporate registration and other

administrative functions

25.19

Since ASIC was established it has been responsible for the

administration of corporate registration. However, in 2012 ASIC also gained

responsibility for the registration of business names after this function was transferred

from the states and territories to the Commonwealth. ASIC also maintains a

register of SMSF auditors. Stakeholders questioned whether it was necessary for

these functions to be performed by a regulator such as ASIC.

25.20

The devolution of ASIC's registry function to another body was noted by

the Governance Institute of Australia as a possible change that could allow

ASIC

to devote resources to its other legislative, surveillance and investigative

responsibilities. To facilitate this, an equivalent of the UK's Companies House

could be established in Australia.[21]

25.21

The committee is not aware of an example of an advanced economy where

the company registration function is undertaken by the securities and markets

regulator.

In a newspaper article published in 2010, former ASIC chairman Alan Cameron was

reported as identifying Pakistan as the only other country where these roles

are combined.[22]

When asked about ASIC's registry responsibilities, the current ASIC chairman

described them as a 'technology business' and 'not really a regulatory

business'. Mr Medcraft also considered there were a number of opportunities

to leverage economies of scale and to create a better user experience by

transforming ASIC's registry function. As an example, he referred to merging

ASIC's corporate register with other government registries:

The Siebel system we have has, currently, six million names

on it. Verizon use the Siebel system in the States for telephones. They have 70

million customers on it. So I think there are huge benefits in actually

separating out that registry business and merging it with other government

registries to leverage the economies of scale from the Siebel management

system. Basically, it has enormous capacity.

What that also means from a consumer perspective is that you

end up with a one-stop shop for financial services and even other registry

things you go to. If you want to update, you want to go to one place et cetera.

And you have to think about the massive opportunity for extracting revenue from

the metadata that actually comes from that.[23]

25.22

Mr Medcraft explained that although ASIC has its newest registers[24]

operating on the more advanced system, ASIC does not have the resources to invest

in the corporate register. Mr Medcraft opined that there 'is cash there for

somebody':[25]

...at the moment we have only two registers on the Siebel

management system. We have the business names and we have the self-managed

super funds. We have not got the capital to invest to bring the corporate

register onto that. If I were in the private sector, I would finance it as a

banker because that $70 million, by moving those registers onto Siebel, would

allow things like person search so every Australian could log on and check

everything a person has to do with ASIC—whether they are deregistered or

whatever. It also allows for online company registration. That $70 million, if

you were in private enterprise, you would invest because the cash flow you

would get out of it would pay back. It is 10-year payback in simple, straight

cash. It removes all the duplication across the registers.

There are economies of scale. Potentially, an investment in

that could eventually yield $350 million of benefits to small businesses

outside of that. So I think the registry is one that probably would be better

moved out, aggregated with other registries to provide a one-stop shop for

Australians.[26]

25.23

A small business owner similarly observed that ASIC's corporate and

business names registers do not appear to have a regulatory role 'beyond

maintaining up-to-date information and not registering conflicting names'. After

expressing criticism about the fees levied on small businesses to fulfil their

obligations to provide information, the fees imposed to access information, and

ASIC's performance at managing

the register, the small business owner concluded that a commercial enterprise

could undertake ASIC's registry functions for less than 'one tenth of the fee

ASIC charges'.[27]

Other submissions also noted the cost of accessing information on ASIC's

register, such as $18 to obtain each current and historical extract of a

company.[28]

25.24

The Governance Institute of Australia observed that ASIC's registry and

other administrative functions, including its call centre, do not utilise

senior or experienced ASIC staff; in fact it indicated that 'call centre staff

appear to be trained only to the extent of referring callers to the ASIC

website in situations where there is uncertainty about the interpretation of

specific provisions'. The Institute argued that:

...there may be service efficiencies to be gained by ASIC

outsourcing its administrative function in a bid to broaden its educative

function. That is, it might be cost-effective for ASIC to use a commercial

operator to run its administrative function rather than maintaining these

responsibilities inhouse.[29]

25.25

The CPSU was asked about the possibility of certain functions being

separated from ASIC and privatised. The CPSU argued that, as the registries

raise

'a reasonably significant source of income and would appear to be a monopoly

service', it would be in the public interest for an Australian government body

to be tasked with the function, rather than the function being privatised.[30]

25.26

Academics also commented on how privatising ASIC's registry function

could affect the provision of information for research purposes. Mr Jason

Harris,

in consultation with other academics, recommended that if ASIC's registry was

privatised, that this only occur with a requirement that information continue

to be provided for research and accountability purposes.[31]

25.27

In May 2014, as part of the 2014–15 Budget, the government announced

that a scoping study would be undertaken into future ownership options for

ASIC's registry function.[32]

Split along clusters or tasks

25.28

Stakeholder organisations and academics also identified other possible changes

to Australia's framework of regulatory institutions. One of the options for

consideration identified by the Governance Institute of Australia was dividing

ASIC into smaller agencies with specific tasks:

[A] number of smaller regulators could be established to

manage the wide range of regulatory functions currently allocated to ASIC,

leaving ASIC focused solely on its original regulatory functions or more

limited regulatory functions than it is currently tasked to manage.[33]

25.29

CPA Australia suggested that thought could be given to restructuring

ASIC and setting clear priorities:

I think it is worth a conversation and some questions perhaps

around splitting ASIC into some segments that can focus on particular things.

When you have a regulator on Monday chasing a corporate, on Tuesday charging a

small business and on Wednesday giving marriage cost advice, that says that perhaps

we need to pause for a moment, set the agenda for the year, tell the public

what they can expect and let's see how accountable you are, because that is

what you keep telling others they have to be.[34]

25.30

Associate Professor David Brown noted the committee's 2010 report that

recommended that ASIC's insolvency functions be transferred to the Insolvency

& Trustee Service Australia (ITSA), since renamed the Australian Financial

Security Authority. Professor O'Brien added that:

...a lot of the rules for that body would come from the best

practice of ITSA, which had shown itself to be a more effective regulator in

that area, because 'insolvency' was in its title as opposed to it being one of

the many functions of ASIC...[35]

Consumer protection

responsibilities

25.31

Some witnesses suggested that the division of consumer protection

responsibilities between ASIC, which has responsibility for consumer protection

in financial products and services, and the ACCC, which has responsibility for

consumer protection in the remaining sectors of the economy, should be

reviewed.[36] Other submissions outlined different proposals. For example, many individuals

dissatisfied with their treatment by ASIC and external dispute resolution

schemes called for the creation of an agency dedicated to consumer protection

in financial services.[37]

A former ASIC employee argued that ASIC has too much work and that this detracts

from ASIC's ability to protect retail investors:

These are the working Australians—the millions of people who

are putting the money into the superannuation system and are least empowered to

protect themselves. They are the ones who need the most protection. I think

they are the ones who have been let down the most by ASIC, and I think the only

way that you can really get them protected is with an agency that is dedicated

to nothing but protecting retail investors.[38]

25.32

In reaching its recommendation that responsibility for consumer

protection in financial services should be transferred from the ACCC to the

agency that ultimately became ASIC, the Wallis Inquiry considered alternative

approaches. In particular, the Wallis Inquiry noted concerns put to it that

without a dedicated consumer protection agency for financial services 'consumer

protection would otherwise become subservient to other objectives'. However,

the report concluded that:

...this risk is more likely to arise where consumer protection

is combined with the functionally different task of prudential regulation. The

tasks of consumer protection, market integrity and corporations regulation are

more complementary than conflicting.[39]

25.33

The approach taken following the Wallis Inquiry was queried at the time[40]

and more recently. In 2008, the Productivity Commission found that the

financial services carve out from the general consumer law occasionally leads

to uncertainty about whether the ACCC or ASIC had jurisdiction. The

Productivity Commission recommended that the economy-wide jurisdiction of the

ACCC for consumer protection be restored but with ASIC continuing to be the

primary regulator for financial services.[41]

Around the time of the Productivity Commission inquiry,

a former ACCC chairman and a former editor of the Australian Financial

Review wrote in various newspaper opinion articles that '[t]he natural home

of financial consumer protection is the ACCC, not the carve-out to ASIC created

by Wallis';[42]

ASIC had a 'noted lack of consumer zeal to date'; and the government should

consider making the ACCC the sole consumer regulator, including for financial

services as '[c]arving out these powers for ASIC has not worked'.[43]

Concerns about the current framework remain; for example, in late 2013 a Monash

University forum on the government's upcoming review of competition policy suggested

that the review should consider whether the ACCC's and ASIC's consumer law

functions 'should be jointly administered by a single separate body'.[44]

25.34

It is noteworthy, however, that recent reforms undertaken in other

countries have not resulted in responsibility for financial services consumer

protection being taken from the securities regulator and given to the general

consumer protection agency. For example, in the United Kingdom the opposite has

occurred.[45]

Proposal for a user-pays funding model

25.35

In addition to suggestions that some of ASIC's responsibilities be

transferred to other bodies, the committee explored how ASIC is funded and

whether the current funding model encourages better regulatory outcomes.

25.36

Although ASIC collects fees, charges and fines on behalf of the

Commonwealth, this substantial revenue ($717 million in 2012–13) is returned by

ASIC to consolidated revenue.[46]

With the exception of some cost-recovery arrangements,[47]

the majority of ASIC's funding has no relationship with the revenue collected

by ASIC.[48]

Nevertheless, the fact that ASIC collects significantly more revenue than its

operating expenses was noted in submissions.[49]

Further, although the growth in revenue from Corporations Act fees appears

steady, Treasury's submission, received in October 2013, noted that ASIC's funding

was projected to decline.[50] In May 2014, the government announced that it would achieve savings of $120.1

million over five years by reducing funding given to ASIC, with ASIC's funding

reduced in the first year by $26 million. The impact of the savings

announced by the government and the termination of various measures are outlined

in Table 25.1.

Table 25.1: Projected funding for

ASIC, 2013–14 to 2017–18 ($ million)

|

($ million)

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

2017–18

|

|

Changes announced in 2014–15 Budget

|

3.0

|

–26.0

|

–32.5

|

–32.1

|

–32.4

|

|

Total annual department expenses*

|

366.28

|

321.25

|

306.04

|

303.40

|

306.29

|

* This

funding relates to ASIC's annual departmental expenses under for its main

functions (in the Budget papers, this is Programme 1.1 under Outcome 1). That

is, ASIC's expenses for the administration of unclaimed money from banking and

deposit taking institutions and life insurance institutions are not included.

Source: Australian Government,

2014–15 Budget: Budget Related Paper No. 1.16, Treasury Portfolio Budget

Statements, May 2014, p. 159.

25.37

The committee reviewed the funding arrangements in place for foreign

regulators. As with ASIC, the US SEC collects fees and has funding linked to

government appropriations. However, the arrangement is different in that there

is more of a direct link between revenue raised and funding.[51]

Another US agency,

the CFPB, primarily receives its funding from the Federal Reserve. Subject to

statutory rules and limits, the CFPB determines the amount of funding necessary

to fund its operations. The funding is not subject to review by Congress.[52]

While these arrangements attract some controversy,[53]

it does provide the CFPB with a relatively stable source of funding.

25.38

An alternative model of funding a regulator already utilised in

Australia and prevalent internationally is based on cost-recovery levies. In

Australia, industry levies are used to fund APRA and, as noted earlier, a small

proportion of ASIC's functions. ASIC's chairman noted that, internationally,

levies are the predominant means by which regulators are funded.[54]

Examples of foreign regulators that receive funding from industry levies

include the UK FCA[55]

and the New Zealand Financial Markets Authority. ASIC also identified that

regulators in Canada, France, Hong Kong and Malaysia are funded through various

forms of levy arrangements.[56]

Other foreign professional bodies such as the US Public Company Accounting

Oversight Board, which oversees audit standards and quality, are similarly

funded through levies imposed on main accountancy firms based on their market

size.[57]

25.39

While not necessarily advocating that ASIC should be funded by industry‑based

levies, Industry Super Australia outlined some of the benefits and

disadvantages it considered such arrangements would have:

It would ensure that the cost of the regulatory framework is

borne by those who give rise to the greatest regulatory burden, so that the

funding is not just borne out of general revenue. That is obviously a clear

advantage. ASIC raises a reasonable amount of revenue in its activities,

particularly in markets. In terms of the disadvantages I suppose it changes the

nature of the relationship that ASIC has with industry. If there are parts of

industry that are providing a greater level of funding, it might alter the

perception of the independence of the regulator from those parts of the

industry.[58]

25.40

ASIC was questioned about its funding patterns and alternative funding

models such as a levy‑based arrangement. Mr Medcraft outlined how, in his

view, ASIC's expanding responsibilities had created a 'problem' with ASIC's

funding model. He explained that when ASIC was established as a corporate

regulator, the fees collected and costs incurred were 'reasonably correlated';

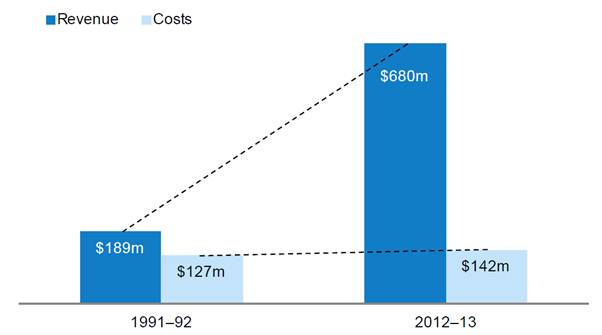

that is, in the early 1990s it cost ASIC around $127 million a year (in nominal

terms) to regulate corporations but it collected around $189 million in

revenue on behalf of the Commonwealth. However, over time this connection has

become weaker. ASIC's costs for regulating corporations have fallen in real

terms to about $142 million, largely as a result of technological advancements.

The revenue from company regulation and business names registration is now

around $680 million, 80 per cent of which comes from small businesses.

25.41

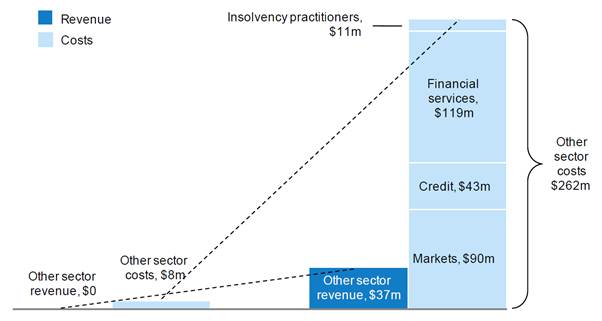

Reflecting the expansion in ASIC's responsibilities since it was

established, ASIC now allocates the majority of its financial resources to its

non-registry functions. ASIC's overall costs are currently around $350 million.

The approximately $260 million in costs that do not relate to corporate

regulation are attributable to three areas of responsibility ASIC has gained

over time: financial services; consumer credit; and markets. Mr Medcraft

explained that of these three growth areas, ASIC has only received additional

revenue associated with the markets function (about $30 million), and even then

only ASIC's frontline costs are recovered.[59]

Therefore, despite the significant financial services and markets functions

ASIC now performs, it could be considered that the revenue streams from

Corporations Act fees effectively results in the burden of funding ASIC

disproportionally falls on small business.

25.42

To further bolster its argument that the current framework may not be

fairly allocating the burden associated with funding ASIC's regulatory

functions, ASIC's chairman advised that:

-

auditors cost ASIC about $6 million a year to regulate but only

pay $425,000 in fees (also, regardless of any difference in the allocation of

resources necessary to regulate large audit firms compared to small firms, both

large and small firms pay $146);[60]

and

-

AFS licensees cost ASIC $108 million a year to regulate but only

pay $3.7 million in fees.[61]

25.43

The following diagrams summarise ASIC's evidence about how the revenue it

collects on behalf of the government and the cost of performing particular

regulatory activities have changed over ASIC's history.

Figure 25.2:

Revenue and costs—companies, business names and searches

1991–2013 (nominal terms)

Figure 25.3: Revenue and costs—all other

sectors 1991–2013 (nominal terms)

Note: Figures are estimates

only, and are not adjusted for inflation. Costs include depreciation. In Figure

25.2, revenue is from companies, business names and searches; costs are from

regulating companies, including administering business names and searches. In Figure

25.3, 'Other sectors' includes insolvency practitioners, AFS licensees, credit

providers, exchange market operators, market participants and consumers. 'Financial

services' includes financial advisers, insurers, responsible entities,

superannuation fund trustees, deposit takers, investment banks, consumers and

custodians.

Source: ASIC, Submission

45.7, pp. 2–3.

25.44

Mr Medcraft stated that he is 'a very big believer in user-pays'.

After reflecting on his evidence about how ASIC's costs and its

responsibilities have changed over time, Mr Medcraft observed that 'those that

generate the need for regulation should pay for that regulation', and that

user-pays systems are 'far more transparent'.[62]

In addition to arguments based on fairness and accountability, ASIC's chairman also

argued that a user-pays levy model could lead to better outcomes for the

financial system. According to Mr Medcraft, a well-designed levy system could

encourage better self‑regulation and lead to more efficient regulatory

outcomes:

The fundamental concept here—from my days in banking—is that

frankly if you provide somebody with the free option, they will take as much of

it as they can get. That is why I think we have to put an incentive into the

system to discourage the use of our resources and that drives an efficient

outcome.[63]

25.45

ASIC subsequently expounded on the argument that a sector-based

user-pays system designed to discourage the use of ASIC's resources could lead

to better outcomes:

At present, there are also no economic incentives (price

signals) in the market for the use of ASIC's resources. Stakeholders acting

rationally will seek to efficiently allocate their own resources and may choose

low-cost or no-cost ASIC services over other, more costly, alternatives

available in the market (e.g. private legal advice).

Price signals associated with the use of ASIC's resources

would allow business to identify the cost of regulation required to achieve the

desired regulatory outcome. If industry can deliver the Government's desired

policy outcomes more efficiently and effectively through co-regulation or self‑regulation,

and therefore require less use of ASIC's resources and cost less to regulate,

they would have an incentive to allocate resources to undertake part or all of

the regulation themselves. This would ensure that the desired policy outcomes

are delivered in the most economically efficient way. However, these price

signals are not currently in place.[64]

25.46

Mr Medcraft observed that the financial incentive such a framework

creates also 'incentivises industry groups':

...I know from running an industry group that one of the

biggest challenges you have is demonstrating your value as an industry group to

your members. If an industry group can actually say to its members, 'Look, if

you sign onto our industry standards and you do a good job and we enforce the

industry standards, we should end up with a lower cost from ASIC because

actually we are achieving the outcomes that government desires.'[65]

25.47

The committee explored how a levy-based system would operate. Mr Medcraft

outlined a model of levies that would be sector-based and adjusted periodically.

Any adjustment would be based on the costs incurred by ASIC in regulating that

sector to achieve an outcome determined by the government. Mr Medcraft

provided the following reasoning:

If you want to have a system that works you really want to

have it such that it is at a sufficiently granular level that, if the industry

does a good job, it should be adjusted both downwards and upwards. Let's take

the audit sector, for example. The government might say, 'We want to make sure

that at least no more than five per cent of audits are poor quality. If the

sector is not achieving that then it needs more effort from ASIC, therefore

more resources.[66]

25.48

ASIC put forward a proposal where $286.55 million (based on its 2012–13

costs) would be recovered from industry through a combination of:

-

fees for service of $37.84 million, where charges are directly

linked to the cost of ASIC delivering a particular service, such as takeover

approvals; and

-

sector-based levies of $248.71 million, where sector participants

pay an annual fee based on 'volume-related metrics'.[67]

25.49

The equity argument put forward by ASIC found some support. Dr Suzanne

Le Mire remarked that ASIC's point on equity 'is well made' and that a levy

system 'has some appeal'. Dr Le Mire noted that the development of levies for

ASIC could be informed by the WorkCover model:

...where you could increase levies for those who step out of

line. Using a model whereby levies are higher for those who break the rules and

lower for those who are consistently compliant would have some appeal and

perhaps give ASIC some purchase that it does not currently have without

pursuing more serious options.[68]

25.50

Dr George Gilligan was relatively supportive of the concept of

introducing

a levy-based funding system, although he indicated that the mechanism for

determining the levies would require careful consideration:

I think from the perspective of equity that it was a fairly

powerful argument when it stated the proportion of the fees that were generated

by lower-scale firms and the amount of regulatory activity or attention that

those firms actually require or receive from the regulator. So there is the

sense that there should be greater proportionality, one would have thought, in

terms of the user pays model. Philosophically, it would be hard to argue

against that. The mechanics may be a little more problematic but, certainly,

one would have thought that there could be different scales of registration or

licensing fees, for example, for the different actors who participate within

the industry, depending on the size scale and, of course, the profits that they

generate from the privilege of having the licence to operate in the industry.[69]

25.51

Professor Dimity Kingsford Smith also recognised that a user-pays levy

would support a regulatory regime that was self-executing. However, Professor

Kingsford Smith cautioned that it was necessary to ensure the public interest was

reflected in any changes:

If you have the entire regulatory revenue coming from levies,

particularly in a concentrated market such as Australia where a lot of the levy

income might come from a very few players, you have to watch out for undue influence

coming from those who pay.

I also would encourage us to do a little bit more research

into the notion that big players always cost more in regulatory resources. I

have had some experience in the UK as well, and there, with their user pays

system, particularly at the compensation-fund end, the big players are always

complaining that it is the smaller players who are having the compensation

payouts from the fund and that because they are big players they pay the levies

but the moneys go out to the clients of the smaller players, who are a bit

harder to keep in line compliance-wise.

So it is not an open and shut case by any means. But having

some of ASIC's income derived from levies could be something very seriously to

consider.[70]

Committee view

25.52

This report has highlighted specific instances where ASIC could have

performed better and considered ways that ASIC could undertake its tasks more effectively

in the future. Some of the problems identified were linked to ASIC's approach

to enforcement, failures to utilise evidence to establish links and problems

with complaints management and stakeholder communication. The committee

considers these are matters that ASIC can largely address on its own initiative.

However, ASIC's long list of regulatory tasks and the resources available to

ASIC

to perform these tasks clearly act as constraints on its ability to meet

expectations the public and stakeholders may have. Neither of these matters are

in ASIC's control; they are matters determined by the government and the

Parliament. To the extent that

a problem with ASIC relates to its funding, it would be unfair to criticise

ASIC.

25.53

Evidence before the committee strongly indicates that ASIC is unfocused

and over-stretched with an evident weakness in consumer/investor protection. ASIC

has always had a significant role in the Australian corporate world, however,

over many years successive governments have entrusted ASIC with additional important

functions. ASIC is now firmly established as one of Australia's key financial

regulators. However, one outcome of this is that it is increasingly difficult

to identify, articulate and prioritise what ASIC's key regulatory functions and

priorities should be. ASIC would have a clearer mandate if it was relieved of

some of its functions.

25.54

The committee noted earlier that in the 2014–15 Budget, the government

announced that it would fund a scoping study to consider options and provide

recommendations on the optimal ownership arrangements for ASIC's registry

function. The scoping study is intended to inform the government on key

strategic policy and implementation issues for consideration before commencing

a sale, licensing or external management process.

25.55

The committee has independently considered suggestions of re-positioning

the function elsewhere. Although these ideas were developed in parallel (one

through a public inquiry process and the other through confidential budget

processes), they both point towards a common point that the operation of a

sophisticated IT database is

a mere enabling function for ASIC and not core to its regulatory role.

25.56

The committee does not consider that it would be appropriate to make a

final decision on where those IT functions should go before the findings of the

scoping study are known. The purpose of scoping studies on government assets is

generally

to identify the most efficient and effective ways of delivering a service to

the public, without a predisposition for any particular model. The committee

fully endorses the work of the scoping study that is examining future ownership

options for ASIC's registry function as an important first step toward

relieving ASIC of its registry function.

Recommendation 49

25.57

The committee recommends that the scoping study examining future

ownership options for ASIC's registry function take account of the evidence

that has been presented to the committee.

25.58

The amount of funding allocated to ASIC through the annual

appropriations process was considered by the committee. For the health of the financial

system it is clearly necessary that ASIC receives an amount of funding that

enables proactive regulation and meaningful law enforcement. However, governments

have competing priorities and the committee recognises the difficulties associated

with increasing ASIC's funding due to the present fiscal circumstances. In any

case, the issue is not limited to the quantum of funding; it is also apparent

that the current model for funding ASIC is outdated and does not promote efficient

outcomes. ASIC regulates many different sectors of the financial system but its

funding does not account for differences in the cost of regulating each sector.

It does not provide an incentive through a price signal for sectors to take

action to limit the amount of resources ASIC allocates to regulating them.

25.59

The committee considers that ASIC should be funded on a user-pays

principle like many of its international counterparts. To implement this, a

framework of sector‑based levies should be introduced to provide the

majority of ASIC's funding. By making regulated entities more accountable for

the cost of regulating their sector,

a clear incentive would be provided for these entities to minimise the number

of problems that the regulator has to deal with. This feature of a

well-designed levy system could, over time, promote more efficient regulatory

outcomes through better self-regulation, resulting in more resources being

available, within existing financial constraints, for the regulator to investigate

misconduct reports and deliberate non‑compliance. The levies would be

reviewed periodically to ensure they are set at appropriate levels and to

provide greater transparency of how ASIC manages its resources. ASIC would need

to justify why it requires the amount of funding

it proposes and industry would have the opportunity to respond to ASIC's

assessment. However, as ASIC would no longer be funded through the Budget

process, the levies should ensure that ASIC's core funding is more stable on a

year-by-year basis and that ASIC has sufficient resources to undertake

proactive regulatory activities.

25.60

A further advantage of a levy model for funding ASIC is that it could

provide a revenue-neutral means for the government to reduce the fees charged for

lodging and inspecting information and documents. The committee considers that

the fees currently charged to the public for accessing information held by a

government body are too high. These fees effectively act as a barrier to

accessing information and potentially counteract efforts to inform the

marketplace and promote the confident and informed participation of investors

and consumers in the financial system. The public interest would be better

served if the size of these fees were significantly reduced. Increased

efficiencies resulting from the committee's recommendation regarding

the transfer of ASIC's registry responsibilities to another agency could also

allow the fees to be reduced further.

Recommendation 50

25.61

The committee recommends that the current arrangements for funding ASIC

be replaced by a 'user-pays' model. Under the new framework, different levies

should be imposed on the various regulated populations ASIC oversees, with the

size of each levy related to the amount of ASIC's resources allocated to

regulating each population. The levies should be reviewed on a periodic basis

through a public consultation process.

25.62

The government should commence a consultation process on the design of

the new funding model as soon as possible.

Recommendation 51

25.63

Following the removal of ASIC's registry responsibilities and the

introduction of a user-pays model for funding ASIC outlined in Recommendations 49

and 50, the committee recommends that the government reduce the fees prescribed

for chargeable matters under the Corporations (Fees) Act 2001 with a

view to bringing the fees charged in Australia in line with the fees charged in

other jurisdictions.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page