Macroeconomic outlook

Budget Resources

Ian Zhou

Introduction

The 2023–24 Budget’s ‘Economic outlook’ (Statement 2 in Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2023–24) provides:

- the

Australian Government’s assessment of the overall health of the Australian economy

- forecasts

of key economic parameters that reflect Australia’s likely economic conditions over

the forward estimates (2024–25 to 2026–27).

Forecasts of key economic parameters underlie many budget figures

and are used in calculating projections of government revenue and expenses. Policymakers,

investors and consumers can use the economic outlook as a guide to inform their

decisions and plans.

Domestic macroeconomic parameters

Compared with the October 2022–23 Budget, the 2023–24 Budget

forecasts for the 6 key domestic macroeconomic parameters have been revised

upwards slightly, indicating a better-than-expected outlook (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Major economic

parameters

Source: Australian Government,

Budget Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1:

2023–24, 6.

Real GDP growth

A key indicator of a country’s economic health is its gross

domestic product (GDP), which measures the total value of all goods and

services produced within a country in a given period. Australia’s real GDP –after

adjusting for inflation – is projected to grow by 1.5% in 2023–24 and then maintain

at least a 2% per annum growth rate over the forward estimates (Budget paper

no. 1, p. 6).

GDP growth is driven by the ‘three Ps’: population,

productivity and workforce participation.

Population

The Budget forecasts total net overseas migration of 1.5 million

people between 2022–23 and 2026–27 (Federal

financial relations: budget paper no. 3: 2023–24, p. 118). Budget paper

no. 1 notes that much of this figure reflects a large temporary increase, with

net overseas migration ‘forecast to be 400,000 in 2022–23 and 315,000 in

2023–24’, followed by a return to normal migration levels from 2024–25.

The Government has attributed

the near-term increase to an influx of international students and working

holidaymakers – rebound effects from the lifting of COVID-19 pandemic

travel restrictions and the subsequent economic recovery. It further argues that

the projected post-COVID recovery in net overseas migration will contribute to restoring

long-term population growth forecasts, reinforcing Australia’s economic rebound

(Budget paper no. 1, p. 39).

Stakeholders in the business and healthcare sectors point

out a critical shortage of skilled workers in their respective industries

and argue it is crucial that skills shortages are addressed as part of the anticipated

population intake (discussed below under the ‘wage price index’ section).

On the other hand, Opposition Leader Peter

Dutton has criticised the Government’s migration policy and noted some of

the challenges regarding the impacts of population growth. In his Budget

reply, Mr Dutton argued:

The Albanese government’s big Australia approach was never mentioned

before the election, but it will make the cost-of-living crisis and inflation

worse … Over five years, net overseas migration will see our population

increase by 1.5 million people. It’s the biggest migration surge in our country’s

history, and it’s occurring at exactly the same time as a housing and rental

crisis. Australians are struggling to rent or purchase a property now … And the

government is now proposing to bring in almost 6,000 people per week, which

will make a very bad situation even worse … A coalition government will

sensibly manage migration, as we’ve done in the past, in conjunction with

proper infrastructure planning.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has responded that migration

forecasts were higher under the former Coalition Government. Treasurer Jim

Chalmers has asserted that ‘Peter Dutton is playing the usual divisive and

dishonest politics when it comes to population’.

The

Age’s chief political correspondent commented on 11 May:

Labor is being pulled in two directions at once. It needs the

migrant intake to sustain economic growth and prevent a recession, but it needs

to keep the number in check to keep faith with Australians who worry that population

growth is too high. It could revise the 1.5 million forecast downward over

time.

If migration does add to inflation, this

impact will potentially be felt more heavily in Queensland, due to internal

migration trends. The Budget includes an assumption that around 99,000 people

will migrate interstate from 2023–24 to 2026–27. Of these, 86,000 people are

expected to move to Queensland, mostly from NSW and South Australia (Parliamentary

Library calculations based on data in Budget paper no. 3, p. 119). This may

create distributional challenges, additional to the nationwide economic impacts

– positive and negative – of aggregate population growth.

For further detail regarding Australia’s migration program

and the evolution of population forecasts since the former Coalition

Government’s March 2022–23 Budget, see the Budget review 2023–24 article

‘Immigration’.

Productivity

Productivity

refers to how much output can be produced with a given set of inputs (labour,

capital, raw materials). Put simply, the more productive a person or a company is,

the more output they can produce with the same levels of input.

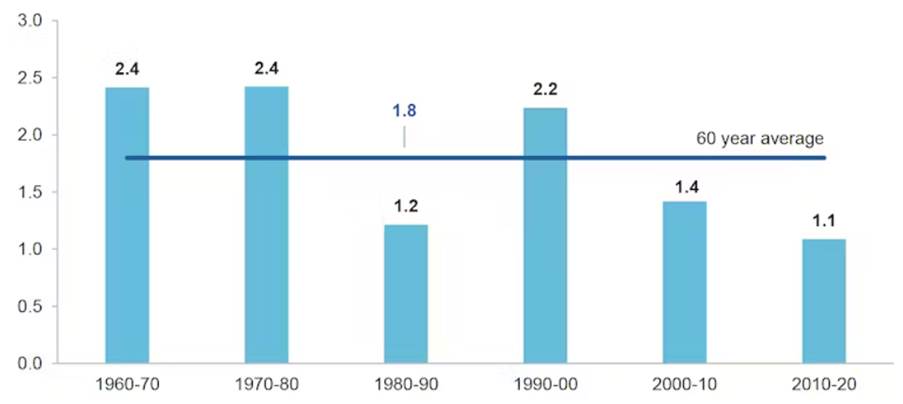

Productivity growth (as measured by labour productivity

growth rate) has been one of the key drivers of increasing living standards and

economic prosperity in Australia over the past several decades. However, Australia’s

productivity

growth has slowed down in recent years to an average of 1.1% (see Figure

2).

Figure 2: Australia’s average labour productivity growth over the past decades

Source: John Hawkins and Craig

Applegate, ‘We know how to boost productivity and lift wages – but

it will take time and much tougher tax reform’, The Conversation, 15 June 2023.

The Treasury expresses concerns that Australia’s

productivity growth and hours worked are expected to decline further as global

warming may push up average temperatures and lead to more frequent and severe

natural disasters (Budget paper no. 1, p. 120). Consequently, the

Government says its Budget fiscal policy is designed to ‘build the capability

of our people, expand the productive capacity of our economy, and support action

on climate change’ (Budget paper no. 1, p. 87).

Business groups have argued the

Government could have done more to promote productivity growth, given the

Budget contains few specific measures to drive business investment. More policies

may emerge when the Government responds to the Productivity Commission’s 5-year

Productivity Inquiry report, Advancing prosperity, and to the parliamentary

inquiry into promoting economic dynamism, competition and business formation.

Participation

The employment-to-population ratio and the labour force participation

rate are at near record-high levels, with the latter at 66.6% in 2022–23. The

participation rate is projected to remain robust at 66.25% over the forward

estimates (Budget paper no. 1, p. 56).

This projection is underpinned by the Government’s promise

to improve women’s workforce participation and economic outcomes (Budget paper

no. 1, p. 18). The October

2022–23 Budget introduced childcare reforms intended to increase the hours

worked in paid employment by women with young children. Parenting

Payment changes announced in this Budget will enable some single parents – 91% of

whom are women – to receive the Parenting

Payment Single instead of the JobSeeker Payment, allowing them to earn more

income before losing eligibility.

Nominal GDP growth

Real GDP growth is adjusted for inflation, while nominal GDP

growth is not. As such, Australia’s nominal GDP growth is directly influenced

by swings in global commodity prices – in particular, the prices of iron ore,

coal, natural gas and agricultural commodities.

Nominal GDP is projected to grow by 10.25% in 2022–23 due to

higher-than-expected commodity prices (Budget paper no. 1, p. 6). The war in

Ukraine has exerted inflationary pressures on food and energy commodity prices

around the world, largely by

driving exceptionally strong global demand for these commodities relative

to available supply. China’s

lifting of COVID-19 restrictions has similarly increased iron ore demand

expectations and hence prices.

Australia is a commodity-exporting country and is

well-positioned to benefit from these elevated prices. Higher-than-expected commodity

prices over the past 12 months have helped to deliver a tax windfall, an

underlying cash balance surplus and strong nominal GDP growth for Australia in 2022–23.

The Treasury says it expects nominal GDP growth to decline

sharply – from 10.25% in 2022–23 to 1.25% in 2023–24 – and then remain low over

the forward estimates, partly because commodity prices are forecast to decline swiftly

to ‘long-term price levels’ (Budget paper no. 1, p. 75). For example, the

Treasury assumes the iron ore spot price will decline from a March quarter 2023

average of US$117 to US$60 per tonne in 2023–24 (Budget paper no. 1, p. 77).

Some of the assumptions are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Commodity price assumptions in the 2023–24 Budget

Source: Budget Paper No. 1, 77.

However, as the Australian Financial Review has

pointed out, federal and state treasuries have a long history

of underestimating commodity prices. Whatever its technical merits, this

approach does allow governments to frame the economic benefits from revising conservative

commodity price forecasts upwards as budget improvements. The Treasury

acknowledges that ‘the commodity price assumptions remain conservative and at

the lower range of market forecasts’ (Budget paper no. 1, p. 73).

Consumer price index

The consumer price index (CPI) is a widely used measure of

inflation. Rising inflation means the goods and services households buy will

cost more, increasing the cost of living: that is, the same incomes will no

longer command the same purchasing power. The Treasury believes inflation in

Australia peaked in late 2022, and that it will moderate as global price shocks

and supply constraints continue to ease. The CPI is forecast to decline from

6.0% in 2022–23 to 3.25% in 2023–24, and to less than 3% over the forward

estimates (Budget paper no. 1, p. 6).

The Reserve Bank of

Australia (RBA) has an inflation target of 2–3%. High inflation over the past 12 months has led the RBA to

pursue a contractionary monetary policy, aggressively raising its cash rate target. The Government says its fiscal policy is

designed to work in tandem with the RBA’s monetary policy to curb inflation

(Budget paper no. 1, pp. 90–91). For example, the Government has committed to

‘avoid fiscal policy adding to inflationary pressures while these are at their

highest’ (Budget paper no. 1, p. 193). The Commonwealth general government

sector was estimated to record an underlying cash balance (UCB) surplus of $4.2

billion in 2022–23. Since the Budget was released, the outlook for this surplus

has improved further, recording

a $19 billion surplus in the year-to-date to May 2023. This surplus could

be construed as a contractionary fiscal policy, where withdrawals (taxes) are

greater than injections (transfers).

Total public sector expenditure, which includes

spending by government-owned enterprises classified as ‘public non-financial

corporations’ or ‘public financial corporations’; fall

outside the ‘general government sector’ and so do not affect the UCB. Total

public sector expenditure was expected to record a negative cash deficit of

$7.8 billion in 2022–23 (Figure 4). This means that government-owned

enterprises are still injecting more money into the economy than they are

withdrawing, which, in principle, could add to inflationary pressures, and

offset some of the benefits of the UCB surplus. For example, the International

Monetary Fund (IMF) argues that fiscal policy may be carried out via

government-owned or controlled enterprises engaged in commercial activities

(IMF, Government

finance statistics manual, 2001, chapter 2, p. 6), not just via general

government sector expenditure.

Figure 4: General government sector’s underlying cash balance vs total public sector’s cash balance

Source: Budget Paper No. 1, 355–66; Australian Government Consolidated Financial Statements

Tables and Data.

The total public sector’s $7.8 billion cash deficit in

2022–23 has led commentators to question the Budget’s narrative of a

contractionary fiscal policy. For example, the Australian Financial Review’s

economics editor argued it was a ‘big

fib that the budget will take pressure off inflation and interest rates’.

He pointed out that after the small $4.2 billion surplus in 2022–23, cumulative

deficits for the general government sector over the next 4 years are forecast

to be $110 billion, with a further $59.6 billion in so-called ‘off budget’

or ‘alternative’

financing of government policies via loans and investment funds. Such a

large injection of money into the economy, he argued, ‘won’t help ease the

pressure on interest rates’. As such, while the continued strong cash inflows

to the Government in May have overshadowed the total public sector cash

deficit, it remains important to consider more than just the UCB when analysing

the complex relationship between inflation and fiscal policy.

Wage price index

The wage price index (WPI) is used to monitor changes in labour

costs over time, which can be indicative of labour market conditions. The

Government argues that the strength of recent labour market outcomes is flowing

through to wages, with nominal wage growth projected to reach 4% in 2023–24 – the

highest rate since 2009. Over the forward estimates, nominal wage growth is forecast

to remain robust at 3.25% or higher (Budget paper no. 1, p. 6).

Robust wage growth typically reflects

a tight labour market with skills shortages. Minister for Home Affairs Clare

O’Neil has stated that the Government will enable the skilled migration needed

to address skills shortages, complemented by medium and longer term efforts to

address domestic skill deficits through education, training and sectoral reforms.

(For further detail, see the Budget review 2023–24 articles ‘Immigration’

and ‘Tertiary

education’.)

Employment and unemployment

The budget papers report that strong employment growth in

Australia has kept the unemployment rate at 3.5% in 2022–23, almost a 50-year

low (Budget paper no. 1, p. 71). Unemployment rates are projected to remain low

by historical standards, rising modestly to 4.25% in 2023–24 and 4.5% in

2024–25. This offers a 2-fold

benefit to the Budget: the Government will need to spend less on welfare

transfers, and it will receive more income tax.

On the other hand, the employment growth rate is expected to

moderate as the economy slows, dropping from 2.5% growth per annum in 2022–23

to 1% per annum over the next 2 years. Despite this deceleration, the Budget

forecasts that the unemployment rate will remain low out to 2033–34, at

Treasury’s assumed Non-Accelerating

Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) of 4.25% (Budget paper no. 1, p.

79).

The NAIRU is the lowest unemployment rate believed to be sustainable

without fuelling wage and consumer price inflation, and is factored into Treasury

and RBA policymaking.

The

Sydney Morning Herald economics editor, Ross Gittins, has questioned the

usefulness of the NAIRU as a policy guide. He has long argued the Treasury sets

the assumed NAIRU too high, leading Australia’s economic managers to accept higher

unemployment than is strictly necessary to keep inflation in check.

Furthermore, while the unemployment rate is an important

economic indicator, in isolation it does not provide a complete picture of Australia’s

labour market or the quality of jobs available.

Outlook for the global economy

Australia is a small open economy heavily reliant on trade

for its economic wellbeing. As such, the budget forecasts for Australia’s

economic health are affected by the global economic outlook.

Elevated inflation, interest rate rises and high levels of

public debt are all expected to constrain growth in advanced economies. Global

economic growth over 2023 and 2024 is projected to be the weakest seen since

the early 2000s, outside of the Global Financial Crisis and pandemic (Budget

paper no. 1, p. 43).

China’s improved outlook, following its rapid transition

from the zero-COVID policy, contrasts with these sluggish growth expectations elsewhere.

Chinese growth may prop up commodity prices and contribute to Australia’s

economic rebound over the forward estimates.

Australia’s growth is expected to exceed that of all major

advanced economies in 2023 (Budget paper no. 1, p. 43). In 2024, Treasury analysis

suggests Australian GDP growth will exceed that of the UK, the Euro area, the US

and Japan, but fall below that of China, India and the world more broadly (Figure

5).

Figure 5: GDP growth of other

countries

Source: Parliamentary Library

calculations based on Budget Paper No. 1, 44.

Sensitivity analysis and

comparisons

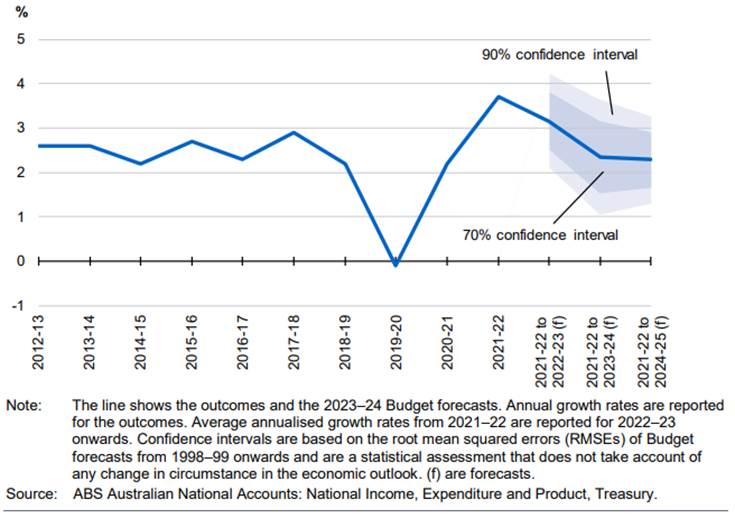

The Budget’s macroeconomic forecasts are underpinned by a

range of assumptions and judgements by the Treasury at the time of preparation.

Some external organisations provide their own assessments of

Australia’s economy, and alternative forecasts of major economic parameters

(Figure 6).

Figure 6: Forecasts of major

economic parameters provided by the Treasury, IMF, RBA and Deloitte Access

Economics

Source: International Monetary

Fund, Australia – Country Data; Deloitte Access Economics, Business Outlook,

March 2023; Reserve Bank of Australia, Statement on Monetary Policy – May 2023.

In practice, economic and fiscal parameters rarely evolve exactly

as forecasted. Such variations can have a significant impact on the Budget – as

noted above. Statement 8 of Budget paper no. 1 provides further information on the

confidence and sensitivity levels of the Treasury’s economic parameter

forecasts. For example, Figure 7 illustrates the range of potential outcomes modelled

for real GDP growth under different scenarios and input assumptions.

Figure 7: The range of potential outcomes modelled for real GDP growth

Source: Budget Paper No. 1, 268.

Deviation from the published forecasts for GDP – and other

economic parameters – will significantly affect the fortunes of future budgets,

for better or worse.