Labour hire

The use of labour hire, 'on hire', or 'agency' workers has

primarily become an avoidance strategy where the legal fiction of a distinct

and separate workforce is used to mask gross exploitation and the shifting of

legal liability that would otherwise reside with the host employer under the Fair

Work Act 2009.[1]

5.1

The term 'labour hire' describes an indirect employment relationship in

which an employer, a 'host' company, instead of employing workers, contracts an

agency to provide workers in return for a fee. There is thus no direct employment

relationship between the host and employee, allowing in some situations the

company to avoid certain employment conditions and responsibilities, and

denying workers the entitlements and protections associated with direct

employment.

5.2

This chapter looks at the use of labour hire through evidence presented

by workers, employers and unions. The chapter focuses specifically on the ways

in which labour hire is used to avoid responsibilities under the Fair Work

Act 2009 (FWA, the Act), examined through case studies presented by

witnesses and submitters.

The growth of labour hire

5.3

Labour hire arrangements have been a feature of the labour market for

decades, however their use has grown steadily across industries in recent

years.[2]

Today Australia is near the top of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) country rankings for the use of agency work.[3]

5.4

The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI) submits that the

use of labour hire is not in itself a deliberate non-compliance with the FWA,

and is instead one of many diverse forms of engagement. ACCI points to a

rapidly and perpetually changing employment environment which requires

flexibility and adaptability from employers, workers and unions:

In today’s society people will undertake multiple types of

work under a variety of arrangements across their working life. There is no

‘one size fits all’ employment model that will suit the circumstances of all

employees or all employers and no single ‘right method’ of labour engagement.[4]

5.5

The Productivity Commission (PC) looked at reasons for the prevalence of

employment forms which differ from traditional ongoing employment arrangements:

The prevalence of alternative forms of employment depends on

the degree to which they meet the needs of employers, match the preferences and

circumstances of workers and are affected by institutional factors. Whether or

not an employer seeks to use a certain form of work depends on their assessment

of how productive and how costly the workers might be.[5]

5.6

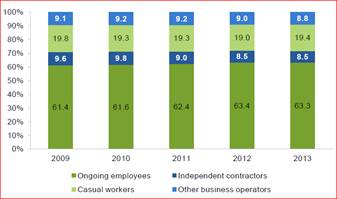

The following figure from the PC indicates that casual workers and other

forms of non-ongoing employment accounted for almost 40 per cent of employment

in recent years:

Figure 5.1—Stability

in the forms of employment, 2009–2013, per cent of total workforce

Source: Workplace Relations Framework, Productivity Commission,

Final Report, 2015, p. 800.

5.7

Details on the incidence of labour hire use are limited. ACCI submitted

that labour hire represents a relatively small percentage of the overall

Australian workforce, approximately 1.2 per cent.[6]

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) reports that there are currently

between 2000 and 3500 temporary agencies operating in Australia, but fewer than

2 per cent of these employ more than 100 workers.[7]

5.8

ACCI cites the PC's view that alternative employment arrangements can

boost productivity and lower costs, and that the benefits of this ultimately

flow to the community as a whole. Furthermore, ACCI quotes the PC's conclusion

that arrangements such as labour hire are 'unlikely to undermine employee

bargaining power to any great extent.'[8]

5.9

The committee received a considerable volume of evidence challenging

this assertion. Although it is indisputable that labour hire arrangements benefit

employers and to a certain extent permit flexibility which might be attractive

to some workers, case studies the committee looked at suggest that labour hire:

-

has a pronounced and disruptive effect on enterprise bargaining;

and

-

is being used by some employers to minimise costs by undermining

the industrial system.

5.10

The critical distinction which must be made is that it is not labour

hire per se that has the above effects, but rather how employers use

labour hire workforces strategically to achieve these outcomes.

5.11

These points are outlined in the following sections.

Disposable workers

5.12

Labour hire was initially envisaged as a way of supplementing existing

workforces. Its continued exemption from mainstream industrial regulation means

labour hire is now also being used to replace existing workforces.[9]

This section looks at what labour hire employment entails.

5.13

Host companies which use labour hire often already have employed workers

performing those jobs, but under the protections of the FWA. Labour hire

involves the provision of labour only, not additional expertise beyond that

held by the company's existing employees. Workers have their services

effectively 'rented out' to clients of the labour hire business.[10]

5.14

Host companies which save on staffing costs by using labour hire

workforces have very few obligations to those workers, who in turn have very

few rights or means to influence their relationship with the host company:

Employers are successfully shielding their profits from the

demands of workers by making a third party employ the workers which shields

them from having to take any responsibility...and having any concern or care for

the welfare of those workers.[11]

5.15

The ACTU describes the use of labour hire as a rejection of the

fundamental policy intent of the FWA, and submits that this manifests in a

number of ways:

- The common law does not see an employment relationship between the host employer

that directs the work and the worker. Further, it has generally rejected the

idea that there could be more than one employer;

-

Labour hire workers cannot bargain for a collective agreement with the

host employer, or participate in bargaining for such an agreement. Whilst

labour hire workers can make a collective agreement with the labour hire agency

(subject to the practical barriers which attach to their predominantly casual

form of engagement), the agency is not the entity that on a day to day basis

controls the work that they perform and the conditions under which and location

where it will be performed;

-

Labour hire workers cannot make an unfair dismissal claim against a host

employer, even where the host employer is the decision maker as to whether the worker

will have a continuing job at the workplace or not;

-

The “General Protections” contained in the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth)

adapt poorly to the work situations of labour hire workers because in the main

they protect the labour hire agency itself from “adverse action” rather than

the workers the agency employs and makes available to workplaces; and

-

Workers in labour hire arrangements are less inclined to speak up about

matters of concern to them as they understand that the decision to request that

they no longer be supplied to the workplace can be made by the host employer at

any time, and may mean they have an uncertain period of time before another

host engagement becomes available.[12]

5.16

Research from the University of Melbourne, cited by the ACTU, finds that

labour hire workers are believed to experience the most volatile weekly hours

of work.[13]

Some workers report being required to be available on the worksite for a full

week, but receiving daily text message notifications telling them whether they

would be required the following working day. Such jobs deny workers the ability

to bargain for better conditions and lack basic security, including the

security of employment needed to obtain a home or car loan.[14]

Labour hire workers, the ACTU submits, 'come closest to the "disposable

worker" model at the heart of the "just-in-time" workforce that

has cemented itself in the Australian labour market over the last twenty-five

years:'[15]

Labour hire is overwhelmingly used as an avoidance strategy

and its continued operation in the present regulatory setting is untenable

unless one accepts that the workers who are engaged by labour hire agencies are

second class citizens.[16]

5.17

In some circumstances, labour hire companies establish opaque corporate

and employment structures. While the leading temporary work agencies operating

in Australia are Skilled, Manpower, Spotless, Programmed Maintenance Services (Programmed)

and Chandler Macleod, these companies often engage subcontractors through

complex and sometimes opaque corporate arrangements which can make it difficult

to ascertain which company a particular worker is actually employed by:

[A] labour hire employee may be legally situated deep within complex

layers of inter-corporate subcontracting arrangements as well as the commercial

arrangements between the labour hire and host. The case reported in Matthew

Reid v Broadspectrum Australia Pty Ltd identifies some of the practical

difficulties that this can present; namely, complying with the practice and

procedure at one's workplace can lead to one being terminated by one's employer

– who is not at one's workplace.[17]

5.18

The federal government has done little to address concerns regarding

labour hire. By contrast, the ACTU reports, some state governments have been

more receptive. In Victoria, for example, the state government has considered

the findings of an extensive inquiry and agreed to establish a system for

licencing labour hire agencies operating in the horticultural, cleaning and

meat industries.[18]

The ACTU reported that a consultation process is currently underway on labour

hire regulation in Queensland and in South Australia, following similar parliamentary

inquiries in those states.[19]

Since that time the committee understands that a bill has been introduced into

the Queensland Parliament to create a labour hire licensing regime in that

state.

Loss of conditions

5.19

Legal Aid NSW submits that using labour hire allows host companies to

avoid paying redundancy entitlements when they no longer require workers. Even

where the worker has spent years performing identical work to an employee of

the host company, that worker is not entitled to a redundancy payment.[20]

5.20

This is particularly problematic where the decision that a worker's

service is no longer required is seemingly unconnected to the worker's

performance or conduct. The CFMEU explains that labour hire workers face

jurisdictional impediments and considerable difficulty in making an application

for an unfair dismissal remedy:

Our members have had their employment terminated after having

worked on a full time basis for one host employer for a considerable time,

often several years. They are often simply told by the labour hire agency that

the host employer no longer desires their presence on site. Because of the

current prohibitions under the unfair dismissal regime in the FW Act, these

labour hire employees do not have any recourse to challenge their dismissals.[21]

5.21

Similarly, even where labour hire workers are dismissed for reasons

relating to performance, this may occur without the worker being accorded

procedural fairness.[22]

5.22

The Act provides certain provisions requiring labour hire companies to

consult with their employees if they are no longer required by the host

company. The labour hire company has, for example, an obligation to consider

redeploying their employee elsewhere; however, this is subject to redeployment

options being available. Legal Aid NSW submits, however, that a large portion

of labour hire employees are engaged on a casual basis, and as such they are

not entitled to redundancy payouts under the FWA.[23]

5.23

The Australasian Meat Industry Employees' Union (AMIEU) reports that

labour hire arrangements help employers minimise their workers' compensation

insurance premiums.[24]

Reduction of corporate responsibility for injuries and deaths at work is of

grave concern, particularly given media reporting around deaths at work in the

building and construction industry, where the use of labour hire is rife and

some construction sites are known for their concentrations of young,

inexperienced workers—unsupervised apprentices, inexperienced backpackers. The

committee notes a recent example, the October 2016 death at a Finbar

construction site in Perth of a young German backpacker, recruited through a

labour hire firm, whose death on site did not prompt the host company to pause

work on site or even contact the police promptly.[25]

5.24

The Queensland Council of Unions (QCU) cites research suggesting that

labour hire is also used as 'a coercive discipline over the workforce by the

threat of unemployment.'[26]

The primary reason employers seek to use labour hire, however, is to reduce

staffing costs.

5.25

The case study below illustrates this point.

Carlton & United Breweries

5.26

Carlton & United Breweries (CUB) produces some of Australia's

best-known beer, including VB, Carlton Draught, Crown Lager and Cascade. The

company has around 1500 workers nation-wide; 420 of these are operational

employees working in breweries. CUB reports significant investment in training

and development, and seeks to position itself as an 'employer of choice' by

providing pay and employment conditions which exceed the National Employment

Standards (NES) and relevant awards.[27]

5.27

CUB has been taking gradual steps to outsource its workforce since 2009.

In 2009, the company outsourced its Abbottsford site in-house maintenance

employees to a labour hire company, ABB. At the time, those workers secured an

enterprise agreement with ABB which 'substantially maintained the majority of

their existing terms and conditions.'[28]

5.28

The labour hire contract was awarded to a new agency, Quant, in 2014,

again with substantially preserved terms and conditions for the maintenance workers.

In late 2015 Quant entered into bargaining with the maintenance workforce and

an Enterprise Agreement, still substantially preserving their terms and

conditions, was voted on in early January 2016, and was still in effect.[29]

However, seven weeks before that contract expired, 55 maintenance workers were

called to an off-site meeting and told that their employment had been terminated.[30]

These workers, who became known as the 'CUB55' during the protracted dispute

which followed, had over 900 years of combined service at CUB between them.[31]

5.29

This was not a last-minute decision by CUB; it was part of a careful,

strategic plan for reducing its expenditure on labour without necessarily

changing its workforce. CUB had a pre-arranged, temporary, replacement

workforce ready and in place on the next working day—labour hire workers flown

in from other breweries, their accommodation paid for—and these workers were

brought in on buses in front of long-serving ex-employees protesting outside.[32]

5.30

The CUB55 workers were told they could re-apply for their jobs, but

through CUB's new labour hire agency, Catalyst Recruitment, a subsidiary of Programmed,

which CUB had entered into a new contract with for the provision of labour hire.[33]

Predictably, the contracts on offer through Catalyst entailed considerable reductions

in pay and conditions. The ETU explained that the Catalyst enterprise agreement

have reduced wages by 65 per cent. It was also a pre-existing agreement which had

lain dormant for five years. Its harsh terms and conditions had in fact been

put in place years earlier, when Catalyst used three casual employees to secure

a non-union enterprise agreement which was in no way connected to CUB.[34]

5.31

Without warning for the workers, Programmed/Catalyst terminated their

contract with CUB around September 2016. The ETU reports that 'CUB refused to

tell the union the terms and conditions upon which the new employees [were]

engaged' at the time.[35]

5.32

Far from being an isolated incident, the AMWU submits that the CUB

example reflects a serious consequence of the nature of the labour hire

industry more broadly:

This unfairness is compounded by the influence of the 'labour

hire' market, where labour hire employers are under competitive pressure to

reduce the amount for which they are prepared to provide the labour, even

though they may not have the labour which they are purporting to be providing.

This particular example at CUB is the norm in many long term labour hire

arrangements, where the incoming labour hire employer attempts to hire all or a

significant proportion of the outgoing labour hire employer's employees.[36]

From the workers' perspective

5.33

The committee received a submission from the CUB55 outlining events at

the Abbotsford brewery. Excerpts from individual workers are provided below,

and tell of the workers' shock at being treated so poorly after years of loyal

service.

CUB55 in their own words[37]

So they sacked us on the Friday, on the Monday there

was already an alternative workforce doing our job. That takes time.

Chris

I’ve worked at the Brewery for 40 years...I’m hardly

labour hire.

Allen

I worked on Thursday 6pm to 6am and I get a phone call,

from a mate actually, not even from the company... I had to go straight after

work, after doing a 12-hour nightshift. So I went to the hotel, and we were

told we were all sacked. They wouldn’t tell us who the contractor was or what

the conditions were, but we were told we could apply for our jobs.

Chris B

We all have a unique set of skills, not the skills you

can just import. Skills that were learned by us over a number of years, that

are unique to this industry. So the injustice of throwing us out, trying to

import skills from all walks of Australia. It clearly hasn’t worked. It would

never work. That is the injustice we all feel.

Paul

The cost on their personal lives is much bigger. You

can’t read it, you can’t see it but everyone is suffering in some way. I am

suffering myself too.

Andy

With this new Agreement there is no provision for us

apprentices anymore...After 4½ years of a 5 year apprenticeship we are now

left, we can’t get our trade certificates...At the end of this year we would

have been qualified in dual trades, electrical and instrumentation, we can’t

get that anymore.

Apprentices

I know I work with the most talented guys in Australia.

We work really hard to get the machinery up to a world class maintainable

standard.

And for that to be thrown away through substandard

practices just breaks my heart. A question a lot of people ask us is, how can

this happen in our country?

I can’t really answer that. I honestly do not know.

Chris

CUB manager's diary entry

5.34

Evidence in the form of a diary belonging to Mr Sebastian Siccita, part

of the CUB management team during the industrial dispute, came to light during

the inquiry. The contents of the diary, which Mr Siccita and CUB's new

management team distanced themselves from when questioned by the committee;

appear to suggest CUB was prepared to stop at nothing to crush its embattled

workers.[38]

5.35

Under the title 'Winning a War', the diary excerpt lists a number of

tactical suggestions, quoted below:

-

Shoot the shit out of them.

-

Play by rules they're not prepared to play by.

-

Cut their supply lines and starve them out.[39]

5.36

The excerpt also includes arrows pointing to the words 'lawyer fees' and

'defamation'. The committee sought clarity on whether CUB had a legal strategy

in place during the dispute, which CUB management confirmed but did not wish to

elaborate on:

At the time, yes, we had lawyers involved. We would certainly

be interested in any attorney-client privilege that would be attached to that.[40]

5.37

The committee notes that Mr Siccita had difficulty recalling whether he

was familiar with the diary or its contents despite leafing through its pages

during a public hearing. Minutes later Mr Siccita contradicted this position by

attempting to retain possession of the diary on the grounds that it was his.

The committee thanked Mr Siccita for confirming that the diary was his.[41]

The resolution

5.38

The committee notes that six months after having their employment

terminated without warning, following large-scale community picket and campaign

and a damaging national boycott of CUB products, the company abandoned its

industrial strategy and all workers were reinstated on agreed pay and

conditions based on those that applied prior to the dispute.

5.39

It is noteworthy that CUB came under new management in late 2016. Unlike

their predecessors, the new management team engaged with workers and the union

for an effective resolution to the dispute, and has committed to a more open,

consultative and positive relationship with its workers and their

representative unions in future:

One of the first acts of our new management team in October

last year was to review the industrial dispute at our Abbotsford brewery and

reach an expeditious resolution. We were pleased that the dispute at the

Abbotsford brewery was successfully resolved within two months of CUB's new

management taking up their new roles Returning operations to normal and

reaching an amicable outcome with the unions and workers was important for our

business in Australia and a statement of how we intend to do business here.[42]

Committee view

5.40

The committee recognises the lack of legal recourse for the CUB55 under

the FWA and therefore the critical role the community campaign and national

boycott played in resolving the CUB dispute. The committee notes that this is

not the only instance of financial pressure coming to bear on a company's

actions.

5.41

The committee wishes to acknowledge that CUB's new management team

engaged with the inquiry process and took responsibility for the company's

actions. The committee particularly applauds CUB's commitment to learning from

the experience and taking proactive steps to ensure that its workers are treated

fairly, with dignity and respect, in future.

Oxford Cold Storage

5.42

The committee was also provided with an example of a company alleged to

have established a number of labour hire companies, as shelf companies, in an

elaborate attempt to avoid negotiating enterprise agreements with its

employees.

5.43

Oxford Cold Storage is one of the largest cold storage warehouses in the

southern hemisphere. The National Union of Workers (NUW) estimates that only 21

workers, out of an approximately 400-strong workforce, are employed directly by

the company. The rest, the union states, are employed through eight different

employing entities—a mix of legitimate labour hire agencies and labour hire

agencies whose workers are employed exclusively at Oxford Cold Storage. It is a

complex arrangement:

In addition, further complicating matters is that four of

those entities at Oxford have enterprise agreements registered to them,

including Daniel's. Daniel is employed by a labour hire agency, you could say,

which has an enterprise agreement which provides for lower pay and conditions

than he is currently working on. So it is a very tenuous and precarious

position that hundreds of the workers at Oxford are in, because technically

their employer is not Oxford; it is a shelf company, more or less, which does

not have office space and does not supply workers to any other worksite but

nonetheless is the entity which technically has control over their pay and

conditions.[43]

5.44

Mr Daniel Draicchio, a worker employed on the site, explained that he

was originally employed by a labour hire agency as a casual, at a lower rate of

pay than full-time workers on site. Mr Draichhio's employment was transferred

through a number of different agencies, and he was eventually placed as a

permanent employee, with better rates of pay and improved conditions. When the

enterprise agreement he was employed under was due to expire, the company asked

Mr Draicchio and fellow employees to sign on with a new agency:

I asked them about the EBA and if we had to negotiate with

that. They said, 'No, an EBA has already been filed with Fair Work; you just

have to sign over once it's been approved.' So we were called back in and

signed over, and that was done; we were on to a new agency. When the EBA

expired for Oxford under the 21 people that were doing negotiations, we were

sent out a letter to say, 'If you don't sign the new common-law contract by a

certain date, your pay will drop.' We did not know what the drop was, because

we had never seen our actual EBA; we had never been told about it. We found out

it was about $7 less an hour than what we are getting now. There are people

that have been there for over 10 years and have never, ever bargained for an

EBA—not once.[44]

5.45

Once workers are made permanent, the company allegedly transfers them

from shelf company to shelf company, always just before a collective agreement

is set to expire, in order to avoid having to negotiate a new enterprise

agreement.

To be clear: the purpose of the transfers—whether it is the

sole purpose or not is difficult for us to say, but it is clearly the main

purpose, in our view—is to deny workers the ability to collectively bargain. So

the transfers occur some months before a collective agreement is set to expire,

and people are transferred to an entity that already has a collective agreement

in place that will run for probably four years. That cycle has occurred a

number of times in relation to a number of different entities at this workplace.[45]

5.46

Despite being moved from employer to employer, the workers continue to

perform the same work, on the same site, throughout.

5.47

The committee contacted Oxford Cold Storage for a response. The company

submitted that it was proud to employ many long-term workers and offered some

of the highest hourly rates of pay in the Victorian cold storage industry. The

allegations above were not addressed.[46]

Industry perspectives

5.48

The Australian Industry Group (Ai Group) advocated for flexible

workplace arrangements, describing them as fundamental to improved

productivity, important for national competitiveness and continuing to raise

Australian living standards.[47]

5.49

The Australian economy, Ai Group submits, faces multiple challenges,

including seismic shifts in the global economy due to continued

industrialisation in populous countries such as China, India and Indonesia, and

a rapid pace of technological development. It is essential, Ai Group holds,

that workplace arrangements in Australia 'remain agile and in a position to readily

adapt to technological changes.'[48]

5.50

In light of this, the committee sought to better understand whether

industry groups acknowledge that there are problems in the labour hire sector,

and what their views are on the challenges insecure work presents for workers.

5.51

The Recruitment and Consulting Services Association (RCSA), Australia's

peak industry body representing employment services, informed the committee

that the association takes steps to monitor and address member organisations'

behaviour:

We do not support, as the RCSA supports, on-hire contractor

or independent contractor services in unskilled, semi-skilled, or even most

trade relationships. We say that it should be the reserve of those who have the

bargaining power, the professional insight and the know-how and the back-end

capacity to manage what is essentially meant to be a business-to-business

relationship. So, if any circumstances arise where we see workers with low

bargaining power—especially unskilled and semi-skilled—being engaged as independent

contractors, we will call out that behaviour with our members under our code,

and we are also prepared to pull them into line to the extent that we have the

power to do so.[49]

5.52

The association has developed an employment certification program which

is designed to address key failures in the sector:

Very simply, it deals with issues of fit and proper people to

run these businesses...The second one is worker status and remuneration, which

goes to the Fair Work entitlements, ensuring that individuals are paid in

accordance with those minimum entitlements; work health and safety;

migration—we are very mindful of vulnerable workers around migration, and we

are working with the foreign worker task force and are about to present to them

on our certification program—and financial assurances as well, making sure that

there is evidence of them having a sustainable and proven record of reporting

and otherwise, so that you do not simply get a mobile phone and say, 'Hey,

here's Jimmy the Afghan's labour hire,' as it was recently referred to in the

media, 'and I can find you a whole heap of people.' The final one relates to

suitable accommodation to try and address the issue of foreign workers being

housed in inappropriate conditions.[50]

5.53

However, the RCSA explained that many complaints around poor conduct

made to its ethics registrar relate to the practices of non-members, and as

such the association is powerless to compel these companies to be bound by a

code.[51]

5.54

Noting that Programmed—the largest labour hire company in the Australian

market and a key player in the CUB case—is in fact a member organisation of the

RCSA, the committee asked whether, in RCSA's view, Programmed had sought to

undermine workers' pay and conditions by seeking to use Catalyst to re-hire the

CUB workforce. In response, RCSA informed the committee that its interest was

limited to ensuring that members comply with legislation:

Our interest there is to ensure that any of our members are

complying with the legislation that applies in the circumstances. I am sure you

and I understand that the Fair Work Act does not prohibit the engagement of

individuals for the purpose of making an enterprise agreement.[52]

Committee view

5.55

The committee notes steps the RCSA is taking to ensure that minimum

standards are adhered to in the labour hire sector. However, this does not

appear to address the key issue around labour hire—the minimum standards do not

set a very high bar, which is precisely the reason that employers are supplementing,

and in some cases replacing, their workforces through labour hire arrangements.

5.56

The committee is disappointed to learn that CUB and Programmed were not

held accountable for their actions during this high-profile dispute, and that

the test for appropriate conduct in the sector is whether employers adhere to

the letter of the law. The committee is firmly of the view that CUB and

Programmed applied an interpretation of the law which suited their financial

interests, with little regard for the spirit of the FWA. Considering that CUB

and Programmed are alleged to have gamed the system by exploiting loopholes in

the FWA—not necessarily contravened the Act—in the committee's view the

question of whether the two companies adhered to the legislation is moot.

5.57

Furthermore, the committee is unconvinced by arguments heard from

industry groups concerning the challenges facing Australia's economy. There is

a propensity to use words such as 'agile' to describe workforces, ignoring the

fact that 'agile' often translates to 'casual' or insecure work. There is a

large body of evidence, on record as part of this inquiry, indicating that

employers are using labour hire specifically to drive down wages and reduce

workers' conditions and entitlements. As explained by the AMWU, by giving

primacy to enterprise bargaining, the FWA in fact ties productivity to wages at

the enterprise level. Labour hire is becoming a vehicle companies are using to

break this connection between productivity and wage increases:

Within this silo of 'labour hire' the work they perform and

the productivity increases they achieve for the business are no longer

connected to their wage increases. Their 'host employer' is insulated by the

'labour hire employer' from any pressure to increase wages.[53]

5.58

In this context, it is worth noting that economists, the governor of the

Reserve Bank of Australia, and the OECD have warned against further stagnation

in wage growth and its deleterious effect on the national economy. Calls for

increasing the use of labour hire and other forms of insecure work are, in the

committee's view, deeply counterproductive and against the national interest.

It is short-sighted to think that allowing wages to fall will have any effect

on the economy beyond redistributing wealth in favour of profits for the

private sector, as shown in Chapter 9 of this report.

Recommendation 2

5.59

The committee recommends that federal and state governments work

together to establish labour hire licensing authorities in each state and

territory, and that licensed labour hire operators be required to provide data

on the numbers of workers engaged.

Recommendation 3

5.60

The committee recommends that the government legislate to require

that a person or organisation supplying a worker to another person or

organisation must:

- be a

licenced labour hire operator; and

- only

engage in such activity through a registered business.

Recommendation 4

5.61

The committee recommends that, upon establishment of labour hire

licensing schemes (Recommendation 2), the government impose a legal obligation

for hosts to use only licensed labour hire providers.

Recommendation 5

5.62

The committee recommends that the National Employment Standards

be amended to provide casual employees, whether directly or indirectly engaged,

the right to elect to become a permanent employee after twelve months regular

and systematic service with the same employer.

Recommendation 6

5.63

The committee recommends that labour hire workers be covered by,

be able to participate in and negotiate collective agreements directly with the

host employer.

Recommendation 7

5.64

Consistent with Recommendation 6, the committee recommends that

host employers have responsibility for ensuring all labour standards provided

in the Fair Work Act are afforded to labour hire workers. Such

provisions could draw on the concept of the Person in Control of a Business or

Undertaking (PCBU) definition found in the Model OHSWHS laws.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page