CHAPTER 7

Wages, conditions, safety and entitlements of Working Holiday Maker (417 and

462) visa holders

Introduction

7.1

Evidence throughout this inquiry highlighted the major role of certain

labour hire companies in the exploitation of Working Holiday Maker (WHM) (417

and 467) visa holders. This chapter focuses on the wages, conditions, safety

and entitlements of WHM visa holders, including the role and prevalence of

labour hire companies operating in both the horticulture and meat processing

industries (matters relating to compliance and recommendations around the

regulation of labour hire companies are covered in chapter 9).

7.2

The chapter begins by examining the additional factors that contribute

to the vulnerability of WHM visa holders, followed by a brief look at proposed

changes to the tax treatment of WHMs.

7.3

The role of labour hire companies in horticulture is then considered. The

bulk of the chapter examines the activities of a web of labour hire companies

supplying labour to Baiada's chicken processing sites in New South Wales (NSW).

This includes evidence of gross exploitation from temporary visa workers

themselves as well as insights from the report of the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO)

into these matters.

Working Holiday Maker visa program

7.4

Evidence from a wide range of submitters and witnesses pointed to the pervasive

exploitation of visa holders other than 457 visa workers. The Migration

Institute of Australia (Migration Institute) noted WHM and student visa holders

were 'consistently reported to suffer widespread exploitation in the Australian

workforce'.[1]

7.5

The Migration Institute pointed to demographic differences as a potential

factor in the greater exploitation of WHM and international students compared

to 457 visa workers. The Migration Institute observed that WHMs and students

are 'generally young, low skilled and with lower than average English language

skills' and typically work in low skill, casual occupations. Furthermore, WHMs

and students do not enjoy the same regulatory protections as 457 visa workers:

They are not protected by the Temporary Skilled Migration

Income Threshold (TSMIT) of a minimum $53 900pa as are 457 visa holders

and they usually undertake work that is low skilled, casual or part time and in

occupations or locations where there may be little choice of employment.

Student and Working Holiday Visa holders are often very reliant on any income

they can get for basic living costs. This makes them more willing to accept

jobs that do not meet legislative levels for Australian income, terms and

conditions and safety standards.[2]

7.6

The Migration Institute was critical of the requirements attached to the

second WHM visa:

The linking of eligibility for a second WHV to three months

employment in regional areas in industries such as horticultural and

hospitality, has exacerbated the problem of employer exploitation amongst this

group.[3]

7.7

In a similar vein, the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU)

recommended that the option of gaining a second year WHM visa should be

abandoned because the requirements for obtaining a second year WHM visa risk

creating the conditions for systemic abuse of backpackers.[4]

7.8

By contrast, the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI)

stressed the economic benefits to Australia of the WHM scheme, in particular

the money spent by WHMs on accommodation, transport and education.

7.9

ACCI also remarked on the reciprocal cultural exchange between Australia

and partner countries, and quoted the following statement from the Joint

Standing Committee on Migration inquiry into WHMs, arguing that the sentiments

remain true today:

The working holiday program provides a range of cultural,

social and economic benefits for participants and the broader community. Those

benefits show that the program is of considerable value to Australia and should

continue to be supported.

Young people from overseas benefit from a working holiday by

experiencing the Australian lifestyle and interacting with Australian people in

a way that is likely to leave them with a much better understanding and

appreciation of Australia than would occur if they travelled here on visitor

visas. This contributes to their personal development and can lead to longer

term benefits for the Australian community.[5]

7.10

The committee notes, however, that in terms of the reciprocal

arrangements between countries party to the WHM program, the FWO reported that

31 Australians were granted a Taiwanese WHM visa in 2013 compared to

15 704 Taiwanese granted an Australian WHM visa for the same period.[6]

Changes to the tax treatment of

Working Holiday Makers

7.11

As noted in chapter 4, the committee received a body of evidence that

WHM visa holders played an important role in the agricultural sector harvesting

perishable goods in regional and remote Australia.

7.12

Given WHM visa holders filled a labour supply shortage during peak

season, the National Farmers' Federation (NFF) expressed concern about the

impact that proposed changes to the tax treatment of WHMs would have on the

future supply of WHMs to Australian agriculture.

7.13

Mr Tony Maher, Deputy Chief Executive Officer of the NFF, noted that the

2015 Commonwealth budget announced changes to the tax treatment of WHMs. WHM

visa holders are currently treated as residents for tax purposes if they stay

in Australia for more than six months:

This gives them access to the tax-free threshold, the

low-income tax offset and a lower tax rate of 19 per cent for income above the

tax-free threshold up to $37 000.[7]

7.14

But from 1 July 2016, WHMs will be treated as non-residents for tax

purposes and will therefore be taxed at 32.5 per cent on all income. Mr Maher

remarked that about 40 000 WHMs work on Australian farms each year

earning, on average, about $15 000 a year in Australia (below the current

tax-free threshold of $18 200).[8]

7.15

Mr Maher was concerned that Australian agriculture could face severe

labour shortages if the changed tax treatment caused a reduction in the number

of WHMs visiting Australia. The NFF therefore proposed a compromise that would

see WHMs taxed at of 19 per cent of their income and not be eligible for the

tax-free threshold, and that the changed tax treatment of WHMs be 'deferred for

later consideration as part of the federal government's broader tax reform process'.[9]

7.16

Noting that WHMs 'inject more than $3.5 billion into the Australian

economy each year', Mr Maher stated that there was a lot of concern from the

business community that WHMs continue to work in rural and remote Australia

rather than just congregating in major holiday destinations.[10]

The NFF also confirmed that it was not consulted before the government

announced the decision to change the tax treatment of WHMs.[11]

7.17

The NFF provided a comparison of the comparable earnings of WHMs (in all

industries) in Australia, New Zealand and Canada, including the hourly rates

and the net hourly rates after tax (see Table 7.1 below). The table shows that

under the government's proposed changes, the net hourly wage of WHMs in

Australia would fall below the comparable rate in New Zealand. But under the

NFF's proposal, the net hourly wage of WHMs in Australia would remain above the

comparable rate in New Zealand.

Table 7.1: Comparable earnings of Working Holiday Makers

|

Country

|

Australia

(32.5%)

|

Australia (19%)

|

Canada

|

New Zealand

|

|

Min. hourly wage

|

$17.29

|

$17.29

|

$10.73

|

$14.75

|

|

Tax rate

|

32.5%

|

19%

|

15%

|

10.5%

|

|

Net hourly wage

|

$11.67

|

$14.03

|

$9.13

|

$13.20

|

Source: National Farmers'

Federation, answer to question on notice, 5 February 2016 (received 15 February

2016).

Exploitation of Working Holiday Maker visa workers by labour hire companies

in the horticulture industry

7.18

Evidence to the inquiry illustrated the different approaches growers in

the horticulture industry used to recruit workers, and the advantages and

disadvantages of the various methods.

7.19

Mr David Fairweather stated that Tastensee Farms did not use labour hire

companies, and instead did all their hiring directly via a web page. Mrs Laura

Wells from Tastensee Farms said she used a Facebook page with about 2500

followers to recruit workers.[12]

7.20

Ms Donna Mogg from Growcom, the peak industry body for fruit and

vegetable growers in Queensland, pointed out that difficulties arise when

workers do not show up for work. Many growers were therefore tempted to use a

labour hire company because the labour hire company takes responsibility for

ensuring that workers arrive for their shifts.[13]

7.21

However, Ms Mogg disputed the assertion that the exploitation of

temporary visa workers was as widespread as the media seemed to suggest:

I say that because we deliver a full and comprehensive

industrial relations advisory service through Growcom, and I would average

around 300 calls from growers every year. These are growers calling me to find

out what they need to do to be in compliance, what their obligations to

employees are and how they better engage with skilling, with local communities,

with local employment coordinators. This is how we know that not every grower

in this state, let alone in this country, behaves in this way.[14]

7.22

Nevertheless, Ms Mogg acknowledged that reports of underpayment,

exploitation and abuse of visa workers in horticulture 'are a matter of great

concern' to the industry and to many growers. She also confirmed 'there are a

lot' of 'fly-by-night phoenix operators' and that they are very difficult to

track down:[15]

And we do believe that it is the labour hire contractors,

particularly recent entrants to the industry—the dodgy ones from overseas, I

guess—who are causing the significant majority of these problems.[16]

7.23

Mr Guy Gaeta, a NSW orchardist, asserted that problems of non-payment

and mistreatment of 417 visa workers in the agriculture sector were associated exclusively

with labour hire companies:

...I represent the New South Wales Cherry Growers Association—I

am in the committee—and I am a delegate to NSW Farmers, and the only problem I

have ever, ever seen with backpackers, with people not getting paid or being

mistreated, is with people that work for contractors.[17]

7.24

Mr George Robertson, an organiser with the National Union of Workers (NUW)

stated that the conditions around the granting of a second year WHM visa render

417 visa workers vulnerable to exploitation, particularly by labour hire

contractors:

But there are a variety of potential problems that can arise

from relying on a particular contractor in order to apply for a second visa. We

have heard stories from members about contractors saying you have to work for

free for X amount of time in order to get a second visa, or you have to provide

sexual favours in order to receive a second visa. That puts workers in a

vulnerable position where their continued presence in the country and their

ability to work and receive a second visa is contingent on whether they agree

with those terms that are provided by the contractors.[18]

7.25

Ms Sherry Huang, a former horticulture worker from Taiwan and now an organiser

with the NUW, explained the mode of operation of a labour hire company.

Typically, the owner of a labour hire company in Australia would set up a

labour hire company in Taiwan and then source all the workers from Taiwan. The

labour hire agency would charge 417 visa holders a fee of several thousand

dollars to arrange flights, accommodation, transport, and a job.[19]

7.26

Ms Lin Pei (Winnie) Yao heard about a job vacancy at Covino Farms

through a friend and was employed to work there by a labour hire company. She

worked as a casual six days a week for 10 or 11 hours a day at $14 an hour,

with a break and lunch.[20]

Mr Robertson noted the Horticulture Award contains no penalty rates for casual

workers and imposes no restrictions on the hours worked by casuals. However, Ms

Yao was still paid substantially less than the award rate of $21.08 an hour.[21]

7.27

Ms Yao never met or spoke to the head contractor from the labour hire

company and never knew the company name. The only contact was by text.[22]

Furthermore, Ms Yao did not receive a payslip, just an envelope with cash

inside. The hours and amount were written on the back of the envelope. Ms Yao

paid no tax. Mr Robertson clarified that 'workers must be provided with a pay

slip that indicates how much they are receiving, how many hours they have

worked, their superannuation and their taxation'. He also noted that in the

poultry processing sector, such cases had been referred to the Australian Tax

Office (ATO).[23]

7.28

Ms Huang confirmed that, in her experience, many 417 visa workers had no

idea about the taxation arrangements in Australia, or indeed that they were not

paying tax:

I can only tell you my experience. I applied for the 417 back

in 2010. I just applied online. The working conditions or working regulations

are all on the Immigration website, which is all English. The backpackers

especially have no idea whatsoever. In terms of talking about a tax issue, they

probably come over here and just want to travel a little bit, earn some extra

money. So they have no idea. Her friend told her, 'Hey, you can find a job this

way,' so she just dialled the number and texted the labour-hire company saying,

'Hey, I need a job.' Even a worker said to me: 'It is the end of the financial

year. How am I going to do the tax?' So they have no idea they are not paying

tax either.[24]

7.29

The head contractor from the labour hire company organised the accommodation,

typically a two or three bedroom house, with two or three backpackers sleeping

in each room. Ms Yao stated that all the backpackers in her house paid $105 a

week in rent each.[25]

7.30

Empirical fieldwork research conducted in 2013 and 2014 across Victoria (Bendigo,

Maffra, and Mildura), Tasmania and the Northern Territory by Dr Elsa Underhill

and Professor Malcolm Rimmer, from Deakin University and La Trobe University

respectively, found that WHM visa workers experience significant vulnerability

in the harvesting sector in Australia and below award average hourly rates of pay.

The level of vulnerability was intensified when WHM visa workers were employed

by a labour hire company rather than employed directly by the grower.[26]

7.31

Dr Underhill and Professor Rimmer found WHM visa workers experienced 'very

low rates of pay when paid piece rates' and that this situation was 'exacerbated

by the Horticultural Award clause on piece rates which refers to 'the average

competent worker'. As a consequence of this clause, it was found that growers

and contractors are able to pay piece rates that do not allow the average

competent worker to earn an amount which approximates that set out in the

award. Dr Underhill and Professor Rimmer therefore recommended:

Replicating the British system of providing a specified

floor, equal to the minimum hourly rate of pay, would overcome the intense

exploitation experienced by piece workers in horticulture.[27]

7.32

Furthermore, the pressures imposed on WHM visa workers by the piece rate

system led to 'a level of work intensification' that enhanced the risk of

workplace injury and led to a 'low level but constant exposure to injury'. At

the same time, the research found visa workers did 'not receive adequate

information and training about the health and safety risks which they are

likely to encounter at work'.[28]

The role of industry associations

in combatting rogue labour hire companies

7.33

Ms Mogg suggested that dealing with a growing number of rogue labour

hire contractors required collaboration between industry and the FWO in order

to ensure that the regulation of the contract labour hire industry is

adequately enforced (this is covered in greater depth in chapter 9). However,

Ms Mogg also recognised the need for industry to work with employers in terms

of advising employers about their compliance obligations, and advising

employers 'not to deal with dodgy operators'.[29]

7.34

In this regard, Growcom had provided advice and support to employers in the

Queensland horticulture sector over a number of years. This included workplace

relations advice, specific resources to assist employers to meet their

compliance obligations, regular training and seminars, and information on workforce

development and planning.[30]

7.35

The South Australian Wine Industry Association played a similar role in

running education and training programs for employers so that they understand

their obligations in terms of workplace and migration law.[31]

Exploitation of Working Holiday Maker visa workers by labour hire companies

in the meat processing industry

7.36

Evidence to the inquiry from the FWO, the Australasian Meat Industry

Employees' Union (AMIEU), and several 417 visa workers themselves, detailed the

extensive exploitation of 417 visa workers at meat processing plants in

Queensland, NSW and South Australia (SA). In this regard, the committee notes

the Four Corners program in May 2015 revealed the exploitation of 417

visa workers at a Baiada poultry processing plant in SA.[32]

7.37

The evidence outlined a litany of activities, many of them illegal,

including below-award wages, non-payment of entitlements under the law,

coercion and threats against union members, substandard and illegal living

conditions in accommodation provided by labour hire contractors, health and

safety conditions, as well as the labour hire business model.

7.38

At the public hearing in Brisbane, Mr Warren Earle, a Branch Organiser

for the AMIEU (Queensland), described what had occurred at the Primo Smallgoods

(Hans Continental Smallgoods) site at Wacol near Ipswich. The site opened in

late 2012 and is the largest smallgoods plant in Australia.[33]

7.39

Primo Smallgoods dealt with a labour hire firm called B&E Poultry Holdings

that was itself a parent company to subsidiary companies. Mr Earle stated that

at the time, the Korean workers on 417 visas got pay slips from two different

companies, Best Link Management and Bayer Management. The pay slips showed the

Korean visa workers were getting between $1 and $3.50 less than the award rate

and 'were not getting paid any overtime, shift penalties or weekend penalties'.[34]

7.40

During this time, approximately 140 Korean 417 visa workers joined the

AMIEU. The AMIEU followed up on the underpayments and secured a six figure sum

in back pay plus superannuation for the Korean workers.[35]

7.41

However, the labour hire company was monitoring the activities of the

Korean visa workers and a representative also sent text messages to the Korean

workers threatening them that they would lose their jobs if they spoke to the

union. Over the next 6 to 12 months, the Korean workers were replaced with

Taiwanese workers on 417 visas. The AMIEU has been informed that the Taiwanese

visa workers have also been threatened that they will lose their jobs if they

approach the union.[36]

7.42

It also appears that the subsidiary labour hire firms are circumventing

the rules that prevent a 417 visa worker from working for more than six months

for any one employer by simply transferring employees from the books of one

labour hire company to the other one.[37]

International labour hire networks

7.43

At the public hearing in Sydney, the committee heard from Mr Grant

Courtney, Branch Secretary of the AMIEU (Newcastle and Northern NSW Branch), Mr

Hoi Ian Tam, International Liaison Officer with the AMIEU, and three 417 visa

workers, Miss Chiung-Yun Chang, Miss Chi Ying Kwan, and Mr Chun Yat Wong.

7.44

Mr Wong recounted that in Hong Kong, he and Miss Kwan had seen an

advertisement on Facebook for work at Baiada in Australia. Mr

Wong and Ms Kwan were subsequently contracted by the labour hire company, NTD

Poultry Pty Ltd (NTD Poultry), to work at the Baiada chicken processing

plant in Beresfield, northwest of Newcastle. NTD Poultry is part of the

multi-layered web of labour contracting firms that supplied workers to the

Baiada processing plants in NSW (see Figure 7.1 later in this chapter).[38]

7.45

The AMIEU also tabled evidence documenting the role played by

international labour hire agencies in the exploitation of 417 visa workers. For

example, agencies in Taiwan such as Interisland and OZGOGO will help labour

hire companies in Australia such as AWX Pty Ltd (AWX) and Scottwell

International to recruit workers.[39]

7.46

Mr Tam stated that agencies in Taiwan charges workers in Taiwan up to

$3000 to organise a job in the meatworks in Australia. However, the workers

often report they have to wait a long time to get a job in Australia and still

have to pay rent to the Australian labour hire company:

Basically, lots of agencies from Taiwan help the labour hire

company in Australia—such as AWX and Scottwell International in Australia—to

recruit workers. This agency from Taiwan requests workers in Taiwan to pay up

to $3000 Australian in order to get a job in the Australian meat industry. They

arrange all the things for the workers like accommodation, induction and other

things. But most of the workers say they cannot get a job and they need to wait

a long time, probably two to three months, until they get a chance to be

inducted. In this time, the workers also need to pay rent to the labour hire

agency. So before they start work, they have already paid A$6000 for this

purpose.[40]

7.47

Miss Chang confirmed that even after paying $3000 in Taiwan and then

having to wait before they can begin induction training, many of her friends

also had to pay an agent called Tim another $1000 to $2000 to work in a meat

factory. Mr Tam noted that Tim works for AWX, so the union believed that AWX also

collects that money.[41]

7.48

The AMIEU provided further documents to support the evidence given by

the witnesses. Tabled document 12 is a Chinese contract issued in Taiwan by a

Taiwanese labour hire company with links to Scottwell International. It offers

two job vacancies, one at an Adelaide beef factory and the other at a Sydney

beef factory. The fees are in in New Taiwanese Dollars (NTD). The contract fee

and overseas fee total NTD $65 000, or just over AUD$2800. In addition,

there is a jobs bond of AUD$600. The pay rates are $18.10 to $21.70, with

overtime paid at the same rates. The period of work is one year, and

accommodation is $80 to $100 a week with a two week bond.[42]

7.49

Tabled document 9 included three Chinese language documents. The first

offered a seminar about working holidays by Australian labour hire company AWX

and Taiwanese labour hire company Interisland. The second offered a package of

meatworks jobs arranged Interisland and AWX for 417 visa workers. The package

required workers to pay NTD $15 000 and AUD$150 a week for rent, AUD$30

for food and AUD$150 for transportation. The third, by Taiwanese company OZGOGO

with links to Australian labour hire company Scottwell International, advertised

jobs for $18 an hour in a meatworks in Murray Bridge, SA.[43]

Illegal training wages

7.50

The committee heard evidence that once the visa workers had arrived in

Australia, the labour hire company exploited them over the conduct and payment

of training prior to their being granted employment in the meat industry.

7.51

As background, Mr Courtney described the long-standing training system

in the meat industry:

We have a very good training system called the Meat Industry

Training Advisory Council [MINTRAC], which the union and the employer

association established about 25 years ago. Most of the people who work in our

industry go through a certificate II in MINTRAC for that purpose, to give them

the food safety competencies and also the standard occupational health and

safety requirements in the position.[44]

7.52

A certificate II must be designed and accredited to adhere to the

specifications of the Australian Qualifications Framework and any government

accreditation standards for vocational education and training. The purpose of a

certificate II is to qualify individuals to undertake mainly routine work and

as a pathway to further learning.[45]

7.53

By contrast, Mr Courtney said that what the 417 visa workers were put

through had 'nothing to do with training'.[46]

Miss Chang described the four week 'training' organised by the labour hire

company, AWX. A series of standard AWX forms tabled by the AMIEU laid out the

evidence on the extent of the deception involved in the AWX training program.[47]

7.54

One week prior to commencing training, Miss Chang had to pay a $300

up-front fee to AWX. The AWX timesheet states that the worker will be paid for

one day's work each week, which will be a total of 9.5 hours at $21.08 an hour

for a total of $200.26 per week before tax. There is also a clause in the

contract stating:

Your wage for the 4th week will be held and paid

with your first week's salary after commencing employment on an AWX site.[48]

7.55

But the training documents only wore the appearance of legality. In

reality, the visa workers worked 50 to 60 hours a week at A. & A. Reid

Enterprise Pty Ltd, trading as Reid Meats in Western Sydney, not the 9.5 hours

on the timesheet. Miss Chang stated that the visa workers started their

training shift at 6.00am and finished at 3.00pm, but often worked overtime

until 4.00pm or 5.00pm. Likewise on the evening shift, they started at 3.00pm

and would finish at 1.00am or 2.00am, a ten or eleven hour shift.[49]

7.56

To add insult to injury, however, once the trainee commenced employment,

the training wages were deducted from the employee's wages in eight weekly

instalments of $100:

After your training is complete and your employment commences

with AWZ; $100 per week will be deducted from your wages for a total of 8 weeks

to cover the remaining training costs.[50]

7.57

Mr Tam explained that, in effect, the visa workers did four weeks of

unpaid work of up 60 hours per week:

For three to five weeks. 'You will still get paid $200 a week

as a living allowance.' It is for their rent, but the pay slip shows the wrong

working hours. Basically, they worked for 50 or 60 hours per week, but the pay

slip only shows nine hours per week and it makes it look legal. Also, after the

workers, like Amy, get a job start at an abattoir, this $200 per week will be

deducted back by AWX, so actually it is no pay.[51]

Below award wage rates and long

hours

7.58

The wages the 417 visa workers at the Baiada site in Beresfield were

getting were well below award rates. Mr Wong stated that the hourly rate was

'close to $12' an hour, with a maximum of $15 an hour over the past half-year.

Mr Wong said the rate cannot be given with certainty because 'it is counted by

kilogram; it is not by hours'.[52]

7.59

Mr Tam said the workers have been unable to get the information that

would allow them to work out their wage calculations:

Every time when the workers want to ask how much they can pay

and how that amount is calculated, the contractor will explain that we will

calculate as a team how much production by kilogram as a formula, and formulate

that amount of money, which is like 0.32 per cent of the whole production, for

which you can get this money. Actually they have no idea how much they produce

and how to calculate the actual amount, and they cannot get the answer.[53]

7.60

Miss Kwan also explained that although the same formula was used for male

and female employees, the women were paid less than the men because they were

doing different work:

Boys can get more than a woman. Maybe $0.50 to $1.

...

Because the girls are only packing or labouring and the boys

will move the meat or do some harder work.[54]

7.61

The 417 visa workers at the Baiada Beresfield site worked long hours.

The minimum hours worked were 12 hours every day, with an overnight

Saturday/Sunday shift of up to 18 hours:

The minimum was 12 hours every day.

...

The longest was on Saturday until Sunday. The hours were very

long. One time we started at 5 pm on Saturday and worked until 11 am on Sunday.

This is a long day.[55]

7.62

Furthermore, visa workers did not always get designated breaks. Rather,

meal breaks were dependent on the urgency of the orders to be completed, with a

toilet break being the only respite:

It is urgent to finish. We will maybe work seven hours with

no break and when you finish the job you will be off duty. But there was no

break.

...

Because I am late shift staff we must be finished all orders

before we can go home. If they were urgent there may be no break for us—only

toilet breaks.[56]

7.63

In addition to the long hours, the entire shift was spent in a

processing plant where the average temperature was between three to five

degrees celsius with short periods of minus 20 degrees celsius in the blast

room.[57]

7.64

Mr Wong raised concerns about workplace health and safety and the

pressures placed on staff to return to work despite suffering work-related

injuries:

I hurt my neck from the working hours, but they just give me

two days off to rest. After that my boss needed me to go back to work, because

they said there was not enough manpower. My section has only two guys to handle

it. When I had a break no-one covered my job. So there was a request that I go

back to work.[58]

7.65

Ms Chang stated that her training contact had a rate of $21 an hour.

However, when she started her employment at the Teys abattoir in Wagga Wagga,

AWX told her the salary started at $16 to $17 an hour:

They told me there was an apprenticeship in Wagga Wagga, but

the salary starts at $16 or $17 per hour. In our training course contract we

were already on $21 per hour. If you do not want that and you cannot accept

that, you are just waiting a long time. We do not have a choice. You just start

at $16 or $17.[59]

7.66

Mr Courtney clarified that $16.86 per hour is the entry level rate under

the award, but that 'no-one in the meat industry generally gets paid the

entry-level rate if they have skills'.[60]

'Voluntary overtime' agreements

7.67

The AMIEU also tabled a standard AWX form that sets out a 'voluntary

overtime' agreement between AWX and an employee. Attached to the document was a

wage slip for the first week of February 2015. The wage slip showed a worker at

George Weston Foods Ltd (trading as Don KRC) in Castlemaine Victoria worked 38

hours at $16.86 per hour and worked an additional 10.25 hours (over 38 hours)

at $16.86 per hour.[61]

Mr Courtney stated that paying $16.86 per hour for overtime hours clearly

breached the Fair Work Act 2009 (FW Act) and the award.[62]

7.68

Mr Courtney expressed disappointment that AWX 'were conducting

themselves the way some of these other sham contracting agencies were',

particularly with regard to the four weeks unpaid training at Reid Meats and

the overtime hours paid at normal rates. Mr Courtney was unsure of AWX's

motivation and whether it was 'a drive to the bottom' or a necessity to compete

with sham contractors and illegal phoenix operators in the labour hire sphere.[63]

7.69

Nevertheless, Mr Courtney noted that AWX was the largest supplier of

labour to Teys Cargill Australia and that 'large companies like Teys are

engaging labour indirectly for the purpose of undermining enterprise

agreements. We can have the best agreement in the world, but it is not worth

the paper it is written on'.[64]

Fake timesheets and no payslips

7.70

Mr Wong also provided the committee with evidence of fake timesheets

produced by the labour hire company NTD Poultry to satisfy new requirements

from Baiada. Sheet 2 of Tabled Document 7 shows the signed Time and Attendance

Record for the tray pack night shift on 3 June 2015. According to the Time and

Attendance Record, the workers started at 5.00pm and finished at either 10.00pm

or 4.00am, a maximum shift of 11 hours. However, NTD Poultry also kept an

actual record of their workers hours in order to pay them. Sheet 1 of Tabled

Document 7 is the true record. It shows worker 56 (Mr Wong) actually worked

from 5.00pm until 8.00am, a shift of 15 hours:

The reason I needed to take this photo is it was very

difficult—very important for the company—and now you can see. No. 1 is the true

hours timetable. They just follow this one. How many hours they pay their

staff. So this one is the real one.

...

This No. 2 document they started 8 June, because they got the

order from Baiada that they needed to do this timetable for Baiada. The first

time, I asked what the reason for the paperwork was, but they did not answer

me. They needed our signature first, and then after you can see the start time

and the finish time. The finish time is empty, and it is clean when we sign it.

We sign it before. So that means that, after we sign it, they can write

whatever they want. Also, after three days I asked, 'Why do we need to sign

this before?' I thought maybe there was a law or something—we make mistakes; we

get trouble. They answered me: 'This one is for Baiada. Also, does not write

down for more than 12 hours for this paper.' So this is the fake hours.[65]

7.71

Miss Kwan and Mr Wong also explained that they never got a payslip from

NTD Poultry, just an envelope with cash inside. AMIEU Tabled Document 8 shows

that on the back of the envelope were the employee number, the date, a kilogram

figure, and a total pay amount.[66]

Local workers unable to secure

enough hours

7.72

There were marked differences not only in the pay that 417 visa workers

received compared to local workers, but also in the hours that they worked. Mr

Tam explained that many of the local workers were not able to get direct

employment and instead had to get work through a labour hire company. However,

the local workers paid at about $27 an hour could only get 16 to 20 hours work

a week when they actually wanted full-time work of 38 hours a week. By

contrast, the 417 visa workers had to work 60 or even 80 or 90 hours a week

when they only wanted 45 hours work a week. The 417 visa workers are paid only

$12 to $15 an hour, whereas the local workers are paid correctly.[67]

7.73

For example, page four of Tabled Document 6 shows three 417 visa workers

at the Baiada plant employed by NTD Poultry worked 93 hours in the week at

$12.50 an hour when they were expecting 40 hours a week. By contrast, page one

shows four local workers paid at $26.46 an hour only getting 21 to 24 hours a

week when they were expecting 38 to 40 hours a week.[68]

7.74

The committee was keen to understand the role that supermarkets play in

this system. Mr Courtney explained that the minimum wage in the meat processing

sector was low compared to other industries, with the average rate for a

labourer in the industry of between $32 000 and $37 000 a year. And yet,

employers such as Baiada have repeatedly told the union that the supermarket

chains dominate the market and can therefore determine the price and they are

driving down prices even further.[69]

Substandard accommodation provided

by labour hire contractors

7.75

Mr Ian McLauchlan, a Branch Organiser for the AMIEU (Queensland),

described the atrocious living conditions of 417 visa workers employed at

Wallangarra Meats on the NSW-Queensland border. At the former Wallangarra

hotel, now backpacker accommodation, the showers did not work and there were up

to four 417 visa workers in small rooms. Elsewhere in Wallangarra, ten 417 visa

workers paid the labour hire company $120 each a week to live in an old home.

They were not allowed to use the heating in winter, the bedding was on the

floor, there was no kitchen table, and they had to set up a rice cooker on

boxes.[70]

7.76

The 417 visa workers in NSW experienced similar conditions in their

accommodation. Miss Chang also had to pay $120 rent per week for a room she

shared with two other people. Another flatmate had to sleep in the living room.

The property owner dealt with AWX.[71]

The AMIEU tabled photographs of the crowded slum-like conditions of visa worker

accommodation provided by labour hire contractors.[72]

Picture 7.1: Accommodation for 417 visa holders employed in

NSW meatworks

Source: Australasian Meat

Industry Employees' Union, Tabled Document 4, Sydney, 26 June 2015.

7.77

Evidence gathered by the FWO during their investigation of Baiada supported

the accounts provided by 417 workers and the unions regarding the benefits that

labour hire contractors derived from exploiting temporary visa workers over

their accommodation. The FWO calculated that the potential annual rental income

accruing to a labour hire contractor from temporary visa worker accommodation

is substantial. For example, one overcrowded Beresfield property was found to

have sleeping accommodation for 21 visa workers employed at the Beresfield

plant. The FWO observed:

Based on 20 people paying $100 per week, the potential rental

income for this property is over $100,000 per year.[73]

7.78

The FWO also documented another case of overcrowded accommodation that

benefitted the labour hire contractor at the Baiada Beresfield site:

Thirty workers engaged within the Pham Poultry supply chain

were housed in a six bedroom house with two bathrooms, with the supervisor

having one bedroom for her exclusive use. Each worker was required to pay $100

per week, deducted from their wages.[74]

7.79

In addition, the FWO found there were no written agreements in relation

to the deductions for rent from the wages of the visa workers. The FWO noted

that deductions for rent are not permitted under the FW Act if the requirement

is deemed unreasonable:

Subsection 325(1) of the FW Act provides that 'an employer

must not directly or indirectly require an employee to spend any part of an

amount payable to the employee in relation to the performance of work if the

requirement is unreasonable in the circumstances'.

Subsection 326(1) provides that a term of a contract

permitting a deduction has no effect to the extent that the deduction is 'directly

or indirectly for the benefit of the employer' and 'unreasonable in the

circumstances'.[75]

Visa manipulation

7.80

The AMIEU also tabled a document they said indicated the manipulation of

the visa system by labour hire agencies both in overseas countries and within

Australia. The alleged scam involved charging 417 visa workers a large fee to

access a protection visa application in order for the worker to gain another 18

months' work in a meatworks in Australia, all the while knowing that the

application would eventually fail:

...one of the main concerns that we have at the moment with the

visa system is the manipulation of the visas across the refugee visa, the 417

visa and, in turn, the bridging visa and student visas. Clearly the ability for

foreign visitors to apply for a protection visa when they arrive in Australia

is a bit of a scam at the moment, the way I see it, because they are being

advised by certain people within Australia and also within their home countries

on how to access continuous work in Australia unlawfully. One of our main

concerns with that is that holders of 417 visas in particular have to pay, and

are being requested to pay, up to $7000 to buy another right to stay in

Australia, and that is about applying for a protection visa or refugee visa. Of

course, once they apply for that visa, they are then given a window of up to 18

months for that visa to be accepted, knowing that that visa will not be

accepted. We have had a range of members that have contacted us—in particular

from the Baiada Beresfield site—that have highlighted what they have paid, and

in some cases it is up to $7000. In turn, if they want to make an application

for a protection visa, it is a $35 application. So they are clearly being

exploited (1) by the advisers in Australia that are providing this information

and (2) by certain labour agents in their home countries milking the system and

making sure they take as much money off these workers as they can.[76]

Approach taken by the AMIEU to

resolving complaints

7.81

The committee questioned the AMIEU over the approach it has taken to

resolving complaints from workers and about the relationship that it has with

employers in the industry.[77]

7.82

Mr Courtney was very clear that the AMIEU looked to work cooperatively

with employers and certainly would not 'name and shame' an employer, firstly,

because the union had a good agreement with the employer and, secondly, because

damage to a company's reputation would be counter-productive in terms of the

ongoing employment and welfare of the workers that they represent. Mr Courtney

stated the issue was not the agreement that the union had negotiated with the

company, but the inequitable treatment of the contracted labour at Baiada:

But, in the discussions that we have had with all of the

employers, particularly Baiada, where we represent over 1000 people in New

South Wales, we have been very up-front with them. We provided the company with

the evidence that we have provided to the Fair Work Ombudsman. We have been

very open with them. We have not tried to hoodwink them. We have not attacked

them publicly. What we have done is expressed our concerns about the

contracting companies they are engaging, especially when we have the best

enterprise agreement rate and the highest union rates in Australia at the

Beresfield site. We can have the highest rates, at $26.50 entry level, but then

you have cases like Skye's and Gypsy's, where they are getting paid $11.50 and

$12.50 on the same site. It is the inequity issue that we have major concerns

about.

...

We have been pressing that point with the employers directly,

because the last thing we want to do is put fear into the community about

buying the product. We have the welfare of our 600-strong workforce to think

of, as well as the good name of the company, we believe—because we have a good

agreement with the company. The problem that we have is those contracted

service arrangements that we are not privy to, and the only time that we can

express an opinion with the company is when we provide them with the

information. They know what the issues are. We do not just pull them out of the

sky. There are 700 at one particular site at the moment that I say are all

being grossly underpaid and treated inequitably.[78]

7.83

In terms of the scale of exploitation, since 2012 Mr Courtney noted that

the AMIEU estimated 417 visa workers were owed $1.26 million in underpayments.

With one labour hire company, Pham Poultry, the AMIEU provided evidence to the FWO

that 32 workers were owed $434 000.[79]

7.84

Since 2011, Mr Courtney indicated that the AMIEU notified the FWO about

visa worker exploitation on most occasions (about 70 per cent). The AMIEU

pursued the rest of the cases directly through the courts.[80]

7.85

However, Mr Courtney also set out two major difficulties in pursuing

court proceedings. First, visa workers only have a limited time in Australia,

and second, companies liquidate as soon as they become aware of any proceedings

against them:

Because of the time constraints in relation to pursuing legal

proceedings and dealing with 417 backpackers—most of the claims are from

backpackers—by the time the matters get before the courts the person is

generally back in their home country. To provide evidence in chief is very

difficult when you are 3,000 or 4,000 kilometres away. We have actually pursued

our own matters as well. The process that we usually follow is: we notify the

circuit court—that is, the application—and then we get in the queue. It is

usually nine months before the matter is mediated. As soon as we notify the

circuit court, the company in question makes an application to liquidate.[81]

7.86

The issue of companies being repeatedly liquidated, and then reappearing

as different companies, has been documented by both the AMIEU and the FWO.

While this phenomenon is covered in greater depth in subsequent sections, the

question of how to regulate illegal phoenix activity is considered in chapter 9.

The Fair Work Ombudsman investigation into the labour hire arrangements of

the Baiada Group

7.87

Following media reports in October 2013 alleging visa worker

exploitation at the Baiada Beresfield plant in NSW, the FWO began an

investigation into the labour procurement arrangements of Baiada at its three

NSW sites, Beresfield, Hanwood and Tamworth. The FWO inquiry began in November

2013 and reported in June 2015.[82]

7.88

The FWO investigation and report are covered at length here because the

findings corroborate the evidence the committee received from both the AMIEU and

417 visa workers.

7.89

The FWO report was scathing of the failure by Baiada to fully cooperate

with the inquiry, noting that:

-

the inquiry encountered a failure by Baiada to provide any

significant or meaningful documentation as to the nature and terms of its

contracting arrangements with businesses involved in sourcing its labour; and

-

Baiada denied Fair Work Inspectors access to its three sites in

NSW which would have provided the inquiry with an opportunity to observe work

practices as well as talk to workers about work conditions, policies and

procedures.[83]

Baiada's contractor operating model

7.90

The FWO report noted that the Baiada Group (Baiada) and Ingham

Enterprises dominated the poultry processing industry in Australia, supplying

70 per cent of the national poultry meat market. Both companies were vertically

integrated entities that owned or controlled all aspects of the production

chain. Baiada included both Baiada Poultry Pty Ltd and Bartter Enterprises Pty

Ltd (the latter purchased in 2009).[84]

7.91

The FWO found Baiada directly employed 2200 employees.[85]

The rest of the processing labour force was procured through a network of

contractors. The FWO found Baiada had agreements to source labour from six

principal contractors: B & E Poultry Holdings Pty Ltd; Mushland Pty Ltd; JL

Poultry Pty Ltd; VNJ Foods Pty Ltd; Evergreenlee Pty Ltd; and Pham Poultry

(AUS) Pty Ltd. Furthermore, 'there was no documentation establishing or

governing' the arrangements between Baiada and the contractors and 'all of

these agreements were verbal agreements'.[86]

7.92

Beyond the principal contractors, the FWO uncovered a web of subcontractors

that in turn engaged further subcontractors. The FWO found the following:

-

the principals contracted to at least seven entities acting as

second tier contractors;

-

the second tier contractors, often contracted down a further two

or three tiers;

-

the principal and second tier contractors were not generally

engaged in the direct sourcing of labour; and

-

the operating model relied upon verbal agreements and operated on

high levels of trust.[87]

7.93

The web of contractors and subcontractors led the FWO to conclude that

Baiada had adopted an operating model which sought 'to transfer costs and risk

associated with the engagement of labour to an extensive supply chain of

contractors responsible for sourcing and providing labour'.[88]

7.94

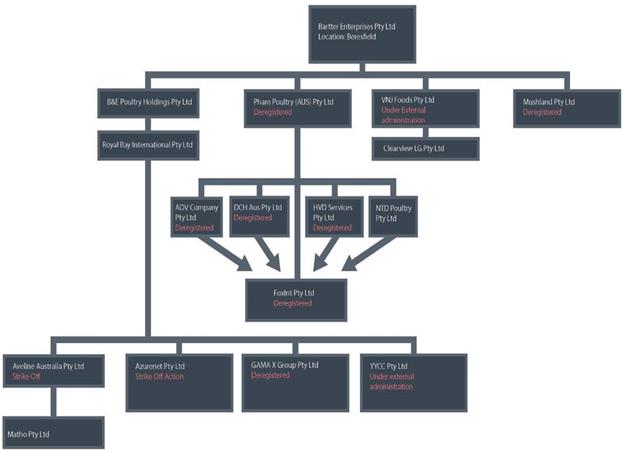

Figure 7.1 (below) shows the labour procurement arrangements identified

by the FWO during its investigation of the Baiada Beresfield site.

Figure 7.1: The labour procurement arrangements at the

Baiada Beresfield site as at 31 October 2013.

Source: Fair Work Ombudsman, A

report on the Fair Work Ombudsman's Inquiry into the labour procurement

arrangements of the Baiada Group in New South Wales, Commonwealth of

Australia, June 2015, p. 19.

7.95

The FWO identified four principal contractors at the Beresfield site.

One of these contractors, B&E Poultry Holdings (B & E), operated its

own processing factories in Ormeau in Queensland and Blacktown in NSW. B &

E had already been the subject of FWO action:

In the last three years 14 requests for assistance have been

received from direct employees of B & E working at the Ormeau site resulting

in recoveries of over $100 000 in underpayments. On 1 August 2014 B & E

entered into a three year Enforceable Undertaking with the FWO in respect of

admitted contraventions by B & E in relation to its direct employees. The

admitted contraventions concerned: underpayment of base hourly rates,

underpayment of casual loadings, overtime rates, weekend penalties and shift

penalties.[89]

7.96

There were substantial differences in the payments made from Baiada to

the principal contractors and those paid by the contractors to the employees.

For example, in October 2013, Baiada paid Mushland Pty Ltd (Mushland) $255 415 and

Mushland paid $52 460 in wages to 18 employees during the same period. This

gave Mushland a margin of $202 954. Mushland was deregistered on 16 July

2014 with no back payment to the underpaid workers.[90]

7.97

Similarly, Baiada paid Pham Poultry (AUS) Pty Ltd (Pham Poultry) $1 078 155

for services provided at the Beresfield site during October 2013. Yet the FWO

found substantial underpayment of the visa workers at the bottom of the supply

chain:

The Pham Poultry arm of the labour supply chain involved four

companies at a tier below the principal, these four companies subsequently

contracted a further tier to a company called FoxInt Pty Ltd (FoxInt). The

director, Quoc Hung Pham, was also a director of the principal Pham Poultry.

Although Pham Poultry directly engaged some workers who were

supervisors at the site, all process workers were engaged by FoxInt. Workers

were paid between $11.50 and $13.50 per hour for shifts of up to 19 hours and

were not paid any leave entitlements or provided payslips. The wages paid to

the process workers at the bottom of this supply chain did not meet the

required minimum entitlements.[91]

7.98

Almost all of the subcontracting companies were deregistered or went

into voluntary liquidation upon investigation by the FWO. Following Pham Poultry's

deregistration, NTD Poultry Pty Ltd (NTD Poultry) replaced Pham Poultry as the

principal contractor. However, the same labour supply chain (with the same

uncontactable director) remained in place:

The labour supply chain operated by NTD Poultry contained the

same entities as those in the Pham Poultry labour supply chain. That is, a

three tier supply model remained in place and the final contractor of labour

FoxInt Pty Ltd, remained, whose Director, Mr Quoc Hung Pham, had been the

Director of Pham Poultry and who could not be located by Fair Work Inspectors.[92]

Figure 7.1: The NTD Poultry supply chain as at January

2014

Source: Fair Work Ombudsman, A

report on the Fair Work Ombudsman's Inquiry into the labour procurement

arrangements of the Baiada Group in New South Wales, Commonwealth of

Australia, June 2015, p. 22.

7.99

Even after NTD Poultry replaced Pham Poultry, the FWO still received

reports of the continuing underpayment of workers getting $11.50 to $12.50 an

hour. In this regard, the FWO made the point that when a contractor or

subcontractor ceased to operate, it was 'very quickly replaced with new 'price

takers', resulting in suppliers of labour being forced into accepting market

prices with no power to negotiate a higher price'.[93]

7.100

Although the FWO endeavoured to investigate NTD Poultry further, it

found that 'workers were reluctant to be witnesses in any ongoing investigation'

and no documentary evidence had been recorded or maintained by the employing

entity.[94]

(The committee therefore notes the evidence in the preceding section from Miss

Chi Ying Kwan and Mr Chun Yat Wong who were both employed by NTD Poultry).

7.101

The FWO was unable to locate the director of Pham Poultry and FoxInt Pty

Ltd, Mr Quoc Hung Pham. The FWO noted that 'the second director of Pham

Poultry, Mr Binh Hai Nguyen, made voluntary payments of $20 250 to 10 workers

to partially rectify the underpayment of entitlements'.[95]

7.102

In terms of the labour hire contractors supplying workers to Baiada, the

FWO found:

-

employees not being paid their lawful entitlements;

-

a large amount of work performed 'off the books';

-

contractors unwilling to engage with Fair Work inspectors;

-

production of inadequate, inaccurate and/or fabricated records to

inspectors;

-

a number of entities throughout extensive supply chain networks

did not engage any workers or have any direct involvement in work undertaken

within Baiada's NSW processing plants or the sourcing or management of labour

undertaking the work;

-

a large number of the entities identified in the supply chains

ceased trading; at times ceasing to exist the day before scheduled meetings

with the FWO;

-

invoices from contractors that were either no longer registered

as businesses or claimed not to be involved in the industry; and

-

workers too scared to talk.[96]

7.103

Related to the above, the FWO uncovered a raft of other issues and

possible contraventions including entities failing to update their details with

ASIC, entities operating when deregistered, sham contracting, subcontracted

entities operating as clothing manufacturers with no apparent connection to the

poultry processing industry, a principal contractor that did not engage any

employees directly, and another principal contractor that only directly engaged

one employee to perform processing work.[97]

7.104

The FWO also found that Baiada paid the 'principal contractors by the

kilogram of poultry processed rather than by hours worked or the times

processing work was performed'. That is, Baiada took no account of whether the

work was undertaken on weekends, public holidays or during a night shift.[98]

7.105

The FWO noted that from 1 July 2014, the Poultry Processing Award 2010

[MA000074] (Modern Award) applied in full across all three Baiada NSW sites for

workers engaged through contractors undertaking poultry processing work. The

FWO also noted the provisions related to piece rates:

Although contractors within the supply chain reported paying

piece rates, the industrial instruments that covered the work undertaken did

not provide for payment of piece rates. In circumstances where piece rates are

provided for in a Modern Award or enterprise agreement, there remains a

requirement to ensure workers receive wages that equate to award minimums.[99]

7.106

In sum, the inquiry found:

-

non-compliance with a range of Commonwealth workplace laws;

-

very poor or no governance arrangements relating to the various

labour supply chains; and

-

exploitation of a labour pool that is comprised predominantly of

overseas workers in Australia on 417 working holiday visas, involving:

-

significant underpayments;

-

extremely long hours of work;

-

high rents for overcrowded and unsafe worker accommodation;

-

discrimination; and

-

misclassification of employees as contractors.[100]

7.107

The FWO recommended a series of actions for Baiada to take in order to

address the issues arising from the investigation. These actions are covered in

the next section.

Baiada's response and the Proactive

Compliance Deed between the Fair Work Ombudsman and Baiada

7.108

Before examining the response from Baiada, the committee notes that the

FWO report emphasised the point that Baiada was the chief beneficiary of the

labour contractor model that it used to source labour and that Baiada had the

power to improve its internal processes and rectify the non-compliance with

workplace laws:

The Inquiry also identified that this operating model

transfers the cost and risk associated with the engagement of labour from the

Baiada Group to labour supply chains of contractors. When contractors are asked

to demonstrate to the Baiada Group that they are complying with minimum

entitlements, they provide very minimal evidence, which appears to be accepted.

...

It is important to note the actual work and subsequent

non-compliance with Commonwealth workplace laws is taking place on premises

owned and operated by the Baiada Group. Baiada Group is therefore the chief beneficiary

of work carried out by this labour force. The Baiada Group has the ability to

take steps to ensure that workplace laws are complied with on their sites.[101]

7.109

In September 2015, Baiada advised the committee that it had instituted 'some

of the most stringent contactor-oversight measures in the industry'. The

following specific measures had been implemented since May 2015:

-

Baiada terminated agreements with three contractors that could

not demonstrate they had sufficient measures in place to ensure compliance with

workplace laws. The termination affected 600 workers (50 per cent of the

contract processing workforce). Those workers agreed to move to an agency

employment provider and nearly all are still working at Baiada sites;

-

Baiada prohibited labour subcontracting such that only entities

in a contractual relationship with Baiada may engage workers at Baiada sites.

Baiada's contractors were prohibited from further subcontracting unless they

receive express written permission to do so from Baiada's Managing Director;

-

Baiada introduced electronic time keeping for contractors'

process workers at Baiada processing sites;

-

Baiada required all remaining contractors to appoint Baiada to

deposit wages directly into contractors' workers' bank accounts. Baiada also pays

all workers' superannuation directly into their superannuation accounts and

ensures all pay-as-you-earn (PAYE) tax is paid directly to the ATO;

-

Baiada entered into new contracts requiring contractors to

improve record keeping, increase transparency, provide detailed reporting,

obtain certificates of compliance from external accounting professionals and

allow third parties to conduct audits of their books;

-

Baiada introduced multilingual (including Mandarin, Vietnamese

and Korean) workplace policies, procedures and information, including

complaints processes, at processing sites. In addition, Baiada established an

onsite translation service and now provides newly inducted workers with the FWO

work rights pamphlets when they commence work at a site;

-

Baiada now confirms that contractors' process workers have the

correct visa status before they are able to commence work at Baiada processing

sites. Once the Visa Entitlement Verification Online (VEVO) checks are

completed, the workers are issued with a Photographic ID Card showing their

name, employer and work rights status. Baiada recently conducted additional

checks of the contractors' workforce to confirm compliance with visa

restrictions relating to hours of work or length of engagement and will conduct

another such check before the end of 2015;

-

Baiada now requires all contractors to provide Baiada with bi-annual

third party compliance audits of their workers' payroll records; and

-

Baiada took advice from specialist workplace consultants, and corporate

law firm Minter Ellison.[102]

7.110

Baiada now has seven contractors at its eight processing plants covered

by ten separate agreements:

-

Adelaide: J & T Trade Pty Ltd;

-

Beresfield: J & T Trade Pty Ltd; and VNJ Holdings Pty Limited;

-

Ipswich: PHV Poultry Pty Limited;

-

Laverton: GGPB Power Pty Ltd;

-

Hanwood: GGPB Power Pty Ltd;

-

Tamworth: GGPB Power Pty Ltd; and HP Food Pty Limited;

-

Osborne Park: Calacash Inwa Enterprises Pty Limited; and

-

Mareeba: Springtime Poultry Pty Limited.[103]

7.111

Mr Grant Onley, Human Resources Manager at Baiada, noted that Baiada charged

the contracting agencies a fee for service for the new payroll services whereby

Baiada deposits wages directly into contractors' workers' bank accounts.

However, Mr Onley stated that 'Baiada is actually losing money on that, but it

is part of our commitment to ensure that workers are paid right. That is part

of our business model going forward'.[104]

7.112

Indeed, Baiada estimated 'the new payroll services arrangements cost the

business in the vicinity of $500 000 per annum' and that this did 'not

include the other non-payroll oversight measures we have introduced at our

sites'.[105]

7.113

Mr Onley noted that Baiada had also invested in other parts of the

business to ensure ethical and lawful business practices were occurring

throughout the organisation:

We have invested heavily in biometrics. Rather than an ID

card that has a photo on it, we are using fingerprint biometric technology in

some of our processing plants. We have certainly engaged consultants to do the

review of the audits. The management time that we have thrown into this is

quite considerable. We have some training requirements with regard to

management and supervisor training going forward that we have committed to.[106]

7.114

On 23 October 2015, Baiada signed a three year Proactive Compliance Deed

(Deed) with the FWO. In the Deed, Baiada acknowledged its responsibilities as a

business to all workers at its sites:

Baiada believes it has a moral and ethical responsibility to

require standards of conduct from all entities and individuals involved in the

conduct of its enterprise, that:

- comply

with the law in relation to all workers at all of its sites, and

- meet

Australian community and social expectations, to provide equal, fair and safe

work opportunities for all workers at all of its sites.[107]

7.115

The Deed also stated that Baiada 'has and will continue to implement

fundamental, permanent and sustainable changes to its enterprise' to ensure

compliance with the FW Act.[108]

As part of these commitments, Baiada agreed to ensure:

-

a dedicated hotline is established for employees to call and make

a complaint if they believe they have been underpaid;

-

workers carry photo identification cards which record the name of

their direct employer;

-

an electronic time-keeping system that records all working hours

of each employee;

-

employee wages can be verified by an independent third party, and

are preferably paid via electronic funds transfer;

-

contractors must be independently audited to ensure their

compliance with workplace laws, with audit results to be provided to the FWO

and published;

-

the company's own compliance with the FW Act is independently

assessed regularly over the next three years;

-

a workplace relations training program is put in place to educate

employees about their workplace rights, including language-specific induction

documents;

-

qualified human resources staff are on-site at each processing

plant to respond to inquiries, complaints and reports of potential

non-compliance;

-

contact details of all labour-supply contractors are provided to

the FWO, including copies of passports of company directors;

-

Fair Work inspectors have access to any worksites and any

documents at any time; and

-

arrangements with contractors are formalised in written contracts

requiring contractors to comply with workplace relations laws.[109]

7.116

Under the Deed, Baiada also agreed to rectify any underpayment of wages

by its labour hire contractors that occurred from 1 January 2015 and set aside

$500 000 for this purpose. Claims could be lodged via a dedicated hotline

or email established by Baiada under the terms the Deed. However, the agreement

only applied to workers who lodged claims before 31 December 2015.[110]

In effect, therefore, workers had about two months to lodge a claim following

the official notification of the offer.

7.117

At the hearing in Melbourne on 20 November 2015, the committee noted

that the AMIEU had provided evidence to the FWO that indicated Pham Poultry and

NTD Poultry, both of which provided workers to Baiada, owed $434 000 to 32

visa workers and $134 000 to 20 visa workers respectively. The committee

was therefore keen to understand why Baiada had limited claims to the period

beginning 1 January 2015 and whether $500 000 was sufficient to cover

those claims. Mr Onley stated that the figure of $500 000 was achieved in

consultation with the FWO and that the FWO had 'agreed with Baiada that

$500 000 for claims post-January 1 is a sufficient amount to cover those

claims'. In response to the evidence of visa worker exploitation going back two

or more years, Mr Onley defended the company by stating that 'Baiada has not

been party to any exploitation of workers'.[111]

7.118

The committee then drew Mr Onley's attention to section C on page one of

the Deed that stated:

Prior to November 2013, the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO)

received requests for assistance from contract workers at Baiada's Beresfield

plant alleging that they were being underpaid by their contractor employer,

forced to work extremely long hours, and required to pay high rents for

overcrowded and unsafe employee accommodation.[112]

7.119

Mr Onley therefore undertook to investigate any information regarding

claims prior to 1 January 2015, to work through it with the FWO, and to take

any such matters to the Baiada board.[113]

7.120

With regard to union engagement, Mr Onley said Baiada had 'an open

dialogue with the NUW and the AMIEU':

I am holding meetings at both a national and a state level

directly with those organisations—Grant Courtney from the AMIEU, Chris Clark

from AMIEU's southern division, and NUW's Alex Snowball; I have met with Alex

again this week. We have given information on the hotline and the process we

are going through, and I have encouraged them to use that process to give us

the information on any claims that they may have or their members may have.[114]

7.121

Baiada advised that as at 20 November 2015, Baiada was investigating 16

claims that met the criteria under the Deed with regard to underpayment.[115]

Mr Onley also pointed out that Baiada had 'taken unlimited responsibility for

any underpayment to contract workers', should it occur in the future.[116]

7.122

On 9 February 2016, Baiada advised the committee that it had reviewed

and processed the claims it received under the terms of its Deed with the FWO. However,

Baiada provided no specific details on the numbers of claims received or

determined:

In the spirit of the proactive compliance partnership, we

have provided the FWO with our proposed response to each claim and believe it

is appropriate to receive the FWO's final concurrence before confirming any

specific information in relation to the claims.

Once consultation with the FWO has been finalised we will

contact the claimants with the outcome of their inquiry along with an

explanation of how the claim was determined.

In the meantime, we are writing to claimants informing them

that we have reviewed their claim, that we are working with the FWO on

finalising the claim and that they will be notified of the outcome as soon as

possible.[117]

7.123

In terms of its internal compliance processes prior to May 2015, Mr

Onley advised that Baiada conducted checks on all its principal contractors and

received 'assurances' from the company directors and 'information from their

accountants in some cases'.[118]

Based on the FWO report, Baiada had agreements at that time to source labour from

six principal contractors for its NSW operations: B & E Poultry Holdings

Pty Ltd; Mushland Pty Ltd; JL Poultry Pty Ltd; VNJ Foods Pty Ltd; Evergreenlee

Pty Ltd; and Pham Poultry (AUS) Pty Ltd.[119]

7.124

In response to a question on notice about the information Baiada had

requested from the directors of the principal contractors and the responses

that Baiada had received from those directors, Baiada undertook to provide the

committee with the information. Baiada provided the committee with:

-

two letters, one it had sent to Mr Xu Chun Dong of B & E

Poultry Holdings Pty Ltd on 19 April 2013, and one it had sent to Mr Binh

Nguyen of Pham Poultry (AUS) Pty Ltd on 19 April 2013;

-

an unsigned letter on Pham Poultry company letterhead stating:

This is to confirm that the company is paying its employees

and other persons engaged in performing the work under our agreement as a

minimum and amount equivalent to the appropriate and current rate as defined by

namely MA000074 – Poultry Processing Award 2010.

Should you have any question regarding this please do not

hesitate to contact us.

-

A letter from Pham Poultry's accountant stating:

Based on records and information supplied, we confirm that

this company is compliant with its obligation in relation to the direct

employees’ entitlements in accordance with Poultry Processing Award 2010

[MA000074].

-

One week of payslips for 12 employees.[120]

7.125

With respect to the above documents, the committee notes the following.

Firstly, Baiada only provided the committee with a response from the director

of one principal contractor and their accountant. Secondly, these are the same

documents examined by the FWO in its investigation of Baiada's labour supply

arrangements in NSW. Thirdly, the FWO reported that payslips showing one week

of wages for 12 employees (one being the Pham Poultry company director) revealed

wage payments totalling $6828.63 compared to payment made by Bartter

Enterprises Pty Ltd to Pham Poultry of $196 307.01 for that week.[121]

Fourthly, on the basis of the above documents, Baiada advised the FWO 'they

were satisfied that Pham Poultry was compliant with Commonwealth workplace laws'.[122]

Fifthly, the FWO was of the view that the above documentation was not able to

support Baiada's conclusion that Pham Poultry was compliant with Commonwealth

workplace laws.[123]

7.126

Given Baiada has stated it was unaware of the level of subcontracting

until after it conducted its own review in May 2015,[124]

a question arises as to why Baiada was satisfied that a principal contractor to

which it paid $196 307.01 for a week's worth of wages in October 2013 was compliant

with all workplace laws when the FWO found that contractor was only making

total wage payments of $6828.63 for that same week.

Committee view

7.127

A substantial body of evidence to this inquiry demonstrated blatant and

pervasive abuse of the WHM visa program by a network of labour hire companies

supplying 417 visa workers to businesses in the horticulture sector and the

meat processing industry.

7.128

It was clear from the evidence that these labour hire companies have a

particular business model. There are a number of labour hire companies in

Australia with close links to labour hire agencies in certain south-east Asian

countries. Workers on 417 visas are recruited from countries such as Taiwan and

South Korea and brought to Australia specifically to work in meat processing

plants. The scale of the abuse is extraordinary, both in terms of the numbers

of young temporary visa workers involved, and also in terms of the exploitative

conditions that they endure.

7.129

Work in a meat processing plant is hard, fast, and potentially

dangerous. The committee heard evidence from the 417 visa workers themselves that

when they arrived in Australia, they often had to wait before they could begin

work, but still had to pay rent to the labour hire company. Work as such began

at a meat processing facility where the temporary visa workers had to undergo a

four to six week 'training' program. The visa workers worked about 60 hours a

week and got paid $200 for 9.5 hours work. However, the labour hire

company recouped its $200 a week outlay, because the four weeks at $200 a week

was deducted from the visa workers' wages once the visa worker was placed in a

'real' job. In practice, therefore, 417 visa workers work 60 hours a week for

four weeks in a meat processing plant and get paid nothing.

7.130

On completion of their 'training', the 417 visa workers were given a job

where they were required to work regular 12 to 18 hour shifts 6 days a week.

They were frequently denied proper breaks and often had to keep working or

return to work early after suffering workplace injuries. The pay rates were

appalling. Most received around a flat $11 or $12 an hour irrespective of

whether this was the night shift, the weekend, or overtime hours. These wage

rates are illegal and clearly breach award minimums.

7.131

Poor or non-existent record-keeping was endemic across the labour hire

companies mentioned in this inquiry. This has serious implications for ensuring

compliance with legal minimum conditions of employment. The 417 visa workers