OVERVIEW

Introduction

This examination of poverty and disadvantage in Australia

was undertaken for two reasons.

Firstly, there is growing evidence within our community that

the strong economic gains of the last two decades have not been shared fairly.

While our economic indicators have continued to reach upwards, so has the level

of inequality, poverty, homelessness and housing stress, long term

unemployment, suicide and child abuse.

Secondly, there has been no comprehensive or wide-ranging

study such as this on poverty for over 30 years. This study was based on the

most reliable, authoritative and up-to-date data available. This was sourced

from:

- Australian Bureau of Statistics;

- Commonwealth Departments;

- charities and welfare organisations with research capacities;

-

private sources; and

- the Committee Hansard recording of hearings made during

the inquiry.

Underpinning our report is how rapid growth of inequality –

especially during the last decade – is driving more and more Australians into

deprivation and disadvantage.

What we found is that Australia is losing the fight for the

fair go, that inequality is accelerating and that there is an increasing loss

of opportunity in our community which denies an increasing number of

Australians a legitimate chance at success.

The Extent of Poverty in

Contemporary Australia

Current levels of poverty in Australia are unacceptable and

unsustainable. Whilst there is considerable academic debate on what constitutes

deprivation, there can be no denying the growth in poverty throughout the last

decade.

The table below indicates a consensus that the numbers of

Australians living in poverty generally ranges from 2 to 3.5 million – with one

study finding 1 million Australians in poverty despite living in a household

where at least one adult works. In addition, there are now over 700 000

children growing up in homes where neither parent works and a great risk that

many youths will never find full-time employment. Without concerted action,

these children and youth will become tomorrow's disadvantaged adults.

Poverty in Australia

– Selected Estimates

|

|

Year

|

Numbers in poverty

|

|

Henderson poverty line

|

1999

|

3.7 – 4.1 million (20.5

– 22.6% of population)

|

|

St Vincent de Paul

Society

|

-

|

3 million

|

|

Australian Council of

Social Service

|

2000

|

2.5 – 3.5 million (13.5

– 19% of population)

|

|

The Smith Family

|

2000

|

2.4 million (13 % of

population)

|

|

Brotherhood of St Laurence

|

2000

|

1.5 million

|

|

The Australia Institute

|

-

|

5 – 10% of population

|

|

Centre for Independent

Studies

|

-

|

5% of population in

'chronic poverty'

|

Sources: See

chapter 3, table 3.1.

This cycle of poverty demonstrates how poverty is becoming

more entrenched and complex. This is evidenced by the fact that the kind of

economic growth Australia is achieving has been unable to lift many Australians

out of poverty.

Importantly, the committee had its attention drawn by a

number of submissions to the close association between poverty and inequality –

and inequality of opportunity. This is illustrative of a marked shift from Australia's

egalitarian traditions, and evidenced in the rapid widening in the income gap

over recent years.

Variation From Average Weekly Household Income – Highest and Lowest 20 per cent of Incomes

* Real Incomes

expressed in constant 1998/99 dollars

Source: Submission 44, p.4 (SVDP National Council).

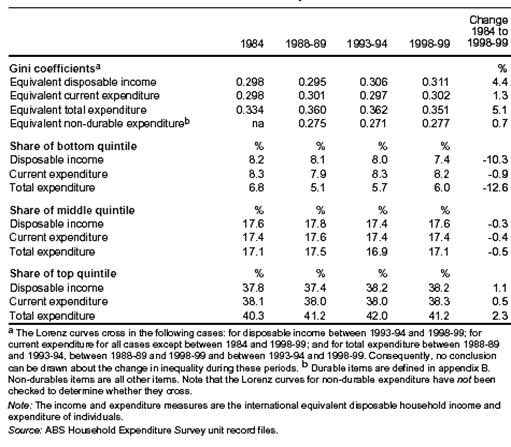

No more clearly is this drawn than by the rapid change in

income inequality and wealth distribution over the last decade. As can be seen

below, the income shares for both the lower and middle quintiles of the

population have decreased – with the middle becoming increasingly polarised.

Gini Coefficient and Shares for Expenditure and Income

The crucial fact is that the widespread financial stress of

poor households is due directly to a decline in their real incomes. It must be

stressed that for the common index of inequality, the Gini coefficient, a

movement of 0.01 has deleterious effects on poverty.

Distribution of Households in Financial Stress -

1998-99

Source:

'Household income, living standards and financial stress', Australian

Economic Indicators, June 2001.

As can be seen above, the reality is that incomes have not

kept pace with the increased costs of services. The deprivation detailed above

is grounded in, and nurtured by, growing inequality and lack of access to such

services. There is now a 'poverty of participation' by the disadvantaged in

institutions of social mobility and security – such as:

- employment;

- education and training;

- health; and

- housing.

Perhaps the most salient example of the prevalence of

poverty and disadvantage is the striking finding that 21 per cent of

households, or 3.6 million Australians, live on less than $400 a week – less

than the minimum wage. The persistence of low-pay and low-incomes arising from

the growth in inequality is clearly the major driver of poverty.

The Reasons behind the

Rise of the 'Working Poor' as the New Face of Poverty

This report has challenged traditional assumptions that

joblessness is often a sufficient reason for the presence of poverty. The

committee has heard that over 1 million Australians are living in poverty

despite living in a household where one or more adults are in employment. By

contrast, the 1975 Henderson report found that only 2 per cent of

households with an adult employed fulltime could be classified as poor. The

rise of the 'working poor' as this group has come to be known demonstrates that

they are the new face of poverty in post-industrial Australia.

The prevalence of working poor households in poverty is due

simply to low-wage employment. Driving this change has been a casualisation of

the workforce in the last two decades and a more recent weakening of the

industrial relations systems. Between August 1988 and 2002 total employment of

casual workers in Australia increased by 87.4 per cent (141.6 per cent for men

and 56.8 per cent for women). By August 2002 casual workers comprised 27.3 per

cent of all employees, an increase of 7 percentage points since August 1991.[1]

The committee has found that this development entails a

radical break with Australian tradition. The main bulwark against poverty since

the Harvester judgement has been secure employment opportunities and just or

living wages. This report has now found that over 1 million Australians are

finding that this certainty has been taken away from them – through no fault of

their own.

The committee found that many members of the low-wage

working poor are placed in similar situations. They are often employed casually

or part-time, in low skill and service industries resulting in little

bargaining power with their employers. Most crucially, their low wages are

unable to be increased due to the inaccessibility of fulltime work or because

of unpaid overtime. Moreover, because of the precariousness and uncertainty of

their employment, career progression and training is often unavailable.

The committee has also found that the rise in workforce

casualisation is the result of attacks on Australia’s traditional industrial

relations system, which emphasised full employment opportunities and provided

protection against attempts to reduce workers job security.

Moreover, the working poor are increasingly finding a

poverty of access to community services due to moves by the current Federal

Government to 'user-pays' models. A salient example of this has been the

impacts on families arising from Medicare bulk-billing. Many working poor

families now not only struggle to afford visits to their family doctor, but are

also more likely to compound their health problems by avoiding visiting the

doctor due to the cost.

Finally, the committee is extremely concerned about the

intergenerational implications of this move away from what has often been

termed the Australian way of ensuring the welfare and prosperity of all

our people. The report has detailed the clear diminution of children's

opportunities and the limitations placed on upward mobility of disadvantaged

families. However, if the processes that have given rise to a new class of

poverty-stricken working people are allowed to continue, then Australia may

never regain its egalitarian tradition.

The Adequacy of Selected

Commonwealth Programs and Payments of Interest to the Inquiry

Almost every submission to this inquiry focused in one way

or another on the role of Government in combating poverty. What united most

submissions – especially those from charities and the community sector – is

that Government should offer a hand up, and not a hand out, to those living in

poverty.

The vast bulk of evidence to the inquiry found that

Government is failing this expectation. On one hand, as the table below

demonstrates, many payments to vulnerable Australians are well below the

poverty line, and must contribute to these people either living in – or being

at risk of – poverty. On the other, the committee found that Government

initiatives are largely failing to provide the necessary opportunities to the

people who need them – especially in the form of employment services and family

payments.

Comparison of Social

Security Payments to the Henderson Poverty Line (including

housing costs) – $ per week, September quarter 2002

|

Family/Income Unit

|

Base Rate

|

FTB A

and/or B

|

Rent Assistance

|

Total Payment

$ per week

|

Poverty line

$ per week

|

Rate as % of poverty line

|

|

Head in Workforce

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Single adult unemployed

|

$185

|

N/A

|

$45

|

$230

|

$294

|

78%

|

|

Single, away from home, 18-20 unemployed

|

$150

|

N/A

|

$45

|

$196

|

$294

|

67%

|

|

Couple unemployed – 0 children

|

$333

|

N/A

|

$43

|

$376

|

$393

|

96%

|

|

Sole Parent unemployed – 1 child

|

$211

|

$101

|

$53

|

$365

|

$378

|

97%

|

|

Sole Parent unemployed – 3 children

|

$211

|

$228

|

$60

|

$499

|

$536

|

93%

|

|

Couple unemployed – 1 child

|

$333

|

$63

|

$53

|

$449

|

$473

|

95%

|

|

Couple unemployed – 3 children

|

$333

|

$190

|

$60

|

$583

|

$632

|

92%

|

|

Head not in Workforce

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Single adult student

|

$151

|

N/A

|

0

|

$151

|

$238

|

63%

|

|

Single student, away from home, 18-25

|

$151

|

N/A

|

$45

|

$196

|

$238

|

82%

|

|

Single Age/Disability Pensioner

|

$211

|

N/A

|

$45

|

$256

|

$238

|

108%

|

|

Age/Disability Pensioner couple – 0 children

|

$352

|

N/A

|

$43

|

$395

|

$338

|

117%

|

|

Sole Parent not in labour force – 1 child

|

$211

|

$101

|

$53

|

$365

|

$322

|

113%

|

|

Sole Parent not in labour force – 3 children

|

$211

|

$228

|

$60

|

$499

|

$481

|

104%

|

Source: ACOSS, Fairness and Flexibility, September

2003, p.41.

Without prejudicing the importance of the working poor in

understanding poverty, unemployment remains a key reason for deprivation and

disadvantage. It is unfortunate then, that the committee has found significant

shortcomings in the Government's Job Network model of employment services that

are failing the unemployed. This is because at no stage is there a significant

guarantee that the long-term unemployed will receive the necessary

case-management or training to find employment through the system. This report

has therefore recommended significant changes to the way the Job Network

operates.

The committee has also had its attention drawn to the

poverty traps created by the present family payments system. This system, which

governs both income support payments (such as Newstart) and family payments

(such as the Family Tax Benefit) creates effective marginal tax rates as high

as 80 per cent. This is because earnings over a certain level attract

additional tax but also result in a reduction in the amount of payment

received. The committee agrees with the many submissions that argued this acts

both as a significant barrier to additional work to increase family incomes and

limits family incomes at a level inappropriate to the circumstances of many

families.

A particularly current debate for all Australians – housing

affordability – has created significant 'housing stress' for those at the lower

end. The inquiry heard that many families are spending over 30 per cent of

their incomes on either rent or mortgage repayments – often to the detriment of

other family expenses. Because of the increases in both rents and house prices

over the last decade, the rise in housing stress is closely linked to lower

disposable incomes, and ultimately poverty. Of concern to the committee was the

lack of interest shown by the current Government in low-cost housing, the

absence of a national housing strategy and a decrease in the Commonwealth's

funding of public housing stock.

Government expenditure on Commonwealth

State Housing Agreement (CSHA) assistance and Commonwealth Rent Assistance

(CRA)

|

|

CSHA assistance

|

|

CRA

|

|

|

$m

|

2001-02 $m

|

|

$m

|

2001-02 $m

|

|

1992-93

|

1485.4

|

1758.7

|

|

1199.0

|

1419.6

|

|

1993-94

|

1419.6

|

1662.5

|

|

1401.0

|

1640.8

|

|

1994-95

|

1509.6

|

1649.4

|

|

1453.0

|

1688.2

|

|

1995-96

|

1489.8

|

1688.4

|

|

1552.0

|

1758.9

|

|

1996-97

|

1353.4

|

1510.1

|

|

1647.0

|

1837.7

|

|

1997-98

|

1207.4

|

1328.4

|

|

1484.0

|

1632.7

|

|

1998-99

|

1276.6

|

1402.3

|

|

1505.0

|

1653.2

|

|

1999-2000

|

1331.0

|

1431.0

|

|

1538.0

|

1653.6

|

|

2000-01*

|

1406.5

|

1442.7

|

|

1717.0

|

1761.2

|

|

2001-02*

|

1392.3

|

1392.3

|

|

1815.0

|

1815.0

|

*CSHA expenditure in 2000-01 and 2001-02 contained

$89.7 million of GST compensation paid to State and Territory Governments.

Source:

See chapter 6, table 6.1.

The committee was also shocked by the nature and extent of

children's poverty throughout the inquiry. Not only were the detrimental

effects to life chances of concern to the committee, but also the extent of

deprivation suffered by children in families living in poverty. In many cases

Commonwealth programs offer little in response to the complex needs of children

– such as literacy interventions, nutrition and parenting skills – where

children are disadvantaged. For this reason the committee has made significant

recommendations in regard to early intervention strategies and support services

for families with poverty stricken children.

Underpinning these selected examples is a common need to

'poverty-proof' community services and rebuild the ladders of social mobility.

This means a linking up of government services at all levels and across

responsibilities to ensure whole-of-government responses to poverty. This

carries with it the recognition that disadvantage is increasingly concentrated

and geographic and hence the implication that such a response must be localised

and holistic.

Whilst the report has a number of recommendations of poverty

interventions, it must be stressed that these must occur in conjunction with

ensuring both employment opportunities for those that can work, and income

dignity for those that cannot.

These key findings presented below serve to illustrate a

compelling case that Australia will face a crisis of poverty and disadvantage

in the coming years. They carry with them the implication that Australians are

increasingly at risk of falling into poverty and indeed more so now than at

anytime during the post-war era.

What is most disturbing however, is the common theme that

while poverty is becoming more entrenched and more intractable, the

Commonwealth is increasingly abrogating its responsibility to tackle this great

indignity inflicted on the Australian people.

Conclusions and Selected

Recommendations

Economic growth is vital but only because it represents the

path to greater prosperity for everyone. The evidence to this inquiry

demonstrates that the kind of prosperity we are achieving is being captured by

a few at the long term expense of the many.

The Commonwealth's indifference to, or acceptance of,

increasing poverty and inequality as the inevitable by product of a market

economy in a globalised world, is out of step with the views of Australians who

believe in a fair go for all.

Indeed this has never been the Australian way. Modern Australia

was founded on a strong economy and a just society. Secure and dignified

employment was the cornerstone of this endeavour. The rise of the working poor

due to casualisation, low pay and the weakening of job security demonstrate how

this thread in Australia's institutional fabric has been torn away.

We ought not automatically assume the solutions of the past

will solve the problems of today. However, this committee has made substantial

recommendations to ensure that we are able to give hope to those Australians

living in poverty in line with our traditions via:

- Removing the poverty traps associated with the Government's family

payments system that acts as barrier to increasing working families' incomes

(recommendation 15);

- Developing a national jobs-strategy to reverse the decline to a

low-skill, low wage economy (recommendation 1);

- Provide employment security and social mobility to casual and

part-time workers through strengthening their employment entitlements

(recommendations 8, 9, 10); and

- Poverty-proofing the minimum wage by linking it to adequate

standards of living and an inquiry into the nature of low-pay in Australia (recommendations

6, 7).

The growing gulf between the headline economic figures and

social outcomes at the community level also requires that key Government social

and economic responses to build capacity be better joined and devolved. Without

whole of government action targeted at economic growth, job creation and

improved social cohesion at a local level, the geographic chasm the St Vincent

de Paul Society describes as 'Two Australias' will only widen.

Nowhere is the 'Two Australias' description more appropriate

than in the level of access to public services and institutions of social

mobility. The committee has found that those Australians living in – or at risk

of – poverty are either finding that many public services are either

inaccessible or more poorly resourced than in areas of lesser disadvantage.

Resolving this requires political will, and it is incumbent on the Commonwealth

to ensure that all Australians are able to access the services they deserve. In

this regard the committee has recommended:

- Ensuring that additional funding for schools is based on the

socio-economic profile and resources of the school concerned (paragraph 7.102);

- Recognising the need for a sustained commitment to bulk-billing,

and for additional population and preventive health measures (paragraphs

8.24-8.25, 8.50);

- The reestablishment of the Commonwealth dental health scheme

(paragraph 8.68);

- Significant reform of the Job Network to ensure that it is able

to provide the necessary and appropriate assistance and training options for

the unemployed (paragraph 4.51);

- The development of national standards of access and adequacy for

public services and a national public infrastructure development plan

(paragraphs 14.43, 14.45); and

- It also recommended that the Commonwealth's presence in local

communities currently provided by Centrelink be bolstered and more focused on

building social and economic capacity (paragraphs 17.93- 17.94).

It must also be stressed that a central reason why poverty

is becoming more entrenched and complex is because of the increasing prevalence

of social risk. Risks such as weak connections to the labour market, poor

educational development and family dysfunction are both symptomatic and causes

of poverty. The 'cycle of poverty' that these risks then create clearly demands

interventions made at both the family, community and individual level that are

sufficiently localised and tailored to break the cycle. Major examples and

recommendations in this report are:

- A national, community based early childhood and parenting skills

and support system (paragraph 11.94);

- A series of initiatives focused around early childhood

development and literacy (paragraphs 7.49-52);

-

Measures to increase school retention and smooth school to work

pathways (paragraphs 7.103-7.104); and

- Expansion of financial counselling services (paragraph 9.52).

There is also a failure on the part of the Commonwealth to

harness institutions such as the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), so

crucial in a Federal system, to coordinate effort to address disadvantage. If

we are serious about tackling poverty and poverty of opportunity, coordinated

effort between Governments (including local governments) is a must.

It is for this reason that the committee has recommended the

development of a National Poverty Strategy. Nothing else can harness the

necessary political will to comprehensively fight poverty. This report has

found that piecemeal and inconsistent responses to poverty are inadequate and

ineffective as long term approaches. The development of the National Poverty

Strategy will involve:

- a summit of Government and key interest groups to highlight the

importance and nature of the issues raised by poverty and poverty of

opportunity and to agree on a broad plan of action;

- a whole-of-government approach through co-ordinated actions

across government and across policy areas; and

- a commitment to action within 12 months.

Following on from this, it is the committee's recommendation

that a statutory authority or unit reporting directly to the Prime Minister be

established to:

- develop, implement and monitor the National Poverty Strategy;

- develop poverty reduction targets against a series of

anti-poverty measures; and

- report regularly to Parliament on its progress.

Finally, the committee would like to stress there is little

room for complacency or delayed action. Although Australia by world standards

is a wealthy country, the level of poverty in our community is increasing and

becoming increasingly entrenched. The committee is compelled to this view after

hearing the daily experiences of Australians living in poverty – from

pensioners who go to bed early because they cannot afford heating and students

slipping into prostitution to support their studies. Indeed it is often the

most vulnerable Australians that are most at risk of poverty, such as:

- children and youth;

-

families with more than one child;

- single parent families; and

- Indigenous Australians.

The indignities these Australians face must not be tolerated

by Government as the unfortunate, but acceptable by-product of modern society.

In the same way that we cannot afford continuing poverty as a nation, we cannot

deny the same life chances to those Australians who most need the opportunity

for a fair go.

Poverty and inequality in Australia today represent a

fundamental test of our national resolve and values. If we are serious as a

community about our claim to be a fair society – indeed the land of the fair go

– then concerted action is required.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page