CHAPTER 3

Private Vocational Education: Business models, marketing practices and

unethical practices

Unscrupulous marketing techniques employed by private providers

3.1

Few issues in the VET sector attracted as much community concern as the conduct

of providers marketing their courses to potential students. The committee

received a swathe of evidence from students, staff and advocates that high

pressure sales pitches aimed at securing students involved practices such as

promises of equipment, downplaying the level of debt the students would incur

and providing deceptive impressions of the qualifications to be earned or

employment opportunities which would follow. These will be discussed more fully

in this chapter.

3.2

Concern about marketing and advertising practice of private RTOs in

Australia's VET sector is entrenched. In 2013, ASQA undertook a review of the

marketing and advertising practices of RTOs in Australia's VET sector, prompted

by what they described as:

serious and persistent concerns raised within the training

sector about registered training organisations and other bodies providing

misleading information in the marketing and advertising of training services.[1]

3.3

This review found that 45.4% of RTOs investigated could be demonstrated

to have breached the national RTO standards and/or consumer and fair trading

legislation, ranging from:

relatively minor concerns that can and should be rectified

quickly and easily, to more serious breaches that could involve major sanctions

being applied, including a loss of the RTO’s registration.[2]

3.4

Specific breaches of the standards found in ASQA's review of marketing

practices amongst RTOs examined in this review included:

-

53.9% marketed qualifications in 'unrealistically short time

frames or time frames that fell short of the volume of learning requirements of

the Australian Qualifications Framework';

-

32.3% had websites which enabled the collection of tuition fees

in advance; half of a sample of these websites allowed RTOs to collect fees in

excess of the amount allowed by the national standards and 60% did not mention

the RTO's refund policy;

-

11.8% advertised superseded qualifications; and

-

8.6% engaged in 'potentially misleading or deceptive advertising such

as guaranteeing a qualification from undertaking their training irrespective of

the outcomes of assessment and guaranteeing a job outcome from undertaking

training even though an RTO is in no position to ensure someone will get a job

as a result of their training'.[3]

3.5

Notwithstanding reforms introduced since the commencement of this

inquiry, marketing practices in the private VET sector remains a key issue for

students, staff and advocates.

3.6

Throughout the inquiry, the committee received evidence about specific

strategies commonly used by private RTOs in marketing courses to potential

students, including:

-

Marketing of courses as 'free' or 'government-funded';

-

Promises of free equipment; and

-

High-pressure marketing techniques and targeting of disadvantaged

people.

3.7

In addition to these, the committee received

evidence about practices such as door-to-door sales, and is aware of

practices such as television advertising and cold-calling. The committee also

notes the practice of promising a certain income or qualifications. Each will

be outlined in this chapter.

3.8

The committee has first considered why this has emerged. Much of this

has to do with the emergence of demand driven student loan schemes like VET

FEE-HELP which have been misused mercilessly by some players in the industry.

The design, and flaws in VET FEE-HELP were covered in chapter 2.

Unsustainable and unscrupulous? The private vocational

education business model

3.9

The introduction of entitlement demand driven funding programs has

created an unprecedented environment in the vocational education sector.

3.10

As noted in chapter 2, the poor design of state based contestable

funding regimes and the VET FEE-HELP program has led to a situation where

students and taxpayers are the victims of a provider-led feeding frenzy.

3.11

Public providers, not for profit providers, and small, quality for

profit providers have lost market share. For profit providers have – in order

to maintain profitability and market share against rivals –pursued

opportunities in government funded markets where volume of enrolments, rather

than quality or outcomes has become the determinant for funding, revenue and

profitability.

3.12

A number of media reports in recent times have described the business

model that has arisen through allowing more open access by private providers to

Commonwealth and state government programs. At the Commonwealth level these

have been VET FEE-HELP and the Tools for Trade programs.

3.13

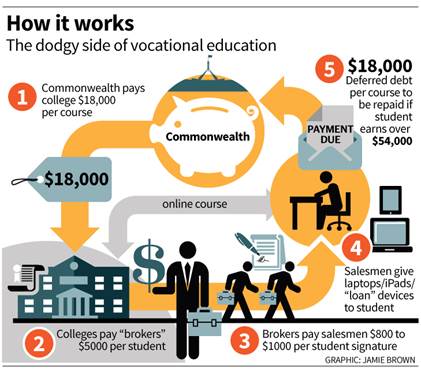

In September 2015, The Age and Sydney Morning Herald

published articles outlining the business model in the vocational education

industry.

3.14

Chapter 5 will deal with issues of regulation, but reports that only 6

or 7 percent of applications to become a RTO have been rejected by ASQA raises

the question of whether the bar has been set too low.[4]

3.15

VET FEE-HELP has seen the evolution of a business model that is

described as such by Michael Bachelard, writing in The Age:

The industry, by design, is "demand driven". But

it's colleges, not students, driving the demand. They employ an army of

salesmen (known euphemistically as "brokers") who earn millions in profits

from taxpayer subsidies.

The dodgy brokers, such as some of those working for

Melbourne's Phoenix Institute, specifically target people living in public

housing, the intellectually disabled, the drug addicted and non-English

speakers.

They offer a free laptop as an incentive to get the signature

of a new "student", then fill out the literacy and numeracy test

themselves (or coach the client through it).[5]

Image from 'Vocational

education, the biggest get-rich quick scheme in Australia', The Sydney Morning

Herald, 16 September 2015, http://www.smh.com.au/national/vocational-education-the-biggest-getrich-quick-scheme-in-australia-20150916-gjnqwe.html,accessed

7 October 2015 and reproduced with the kind permission of Fairfax Media.

3.16

The picture painted is one of problems at the

margin of the private vocational education sector. According to Mr Rod Camm,

from ACPET,

I certainly believe that there are

quality issues, but they are at the margins of the industry. If you look at

numbers of providers, the majority are delivering a quality product and are

doing the right thing. But that is not to say that there have been no problems.

It is on the public record that there have been major problems.[6]

3.17

Media reports, which highlight the

activities of brokers who almost exclusively come from multicultural

backgrounds, serve to reinforce the impression of problems that exist at only

at the margins of the industry.

3.18

But such has been the scale of change

in the private vocational education industry in recent years, can it be

accurately said that the companies that benefit from an exploitative business

model are now a small part of the industry?

Growth,

change and the rise and fall of education stocks

3.19

One major feature in the private

vocational education sector has been the scale of growth and change in recent

years. According to the submission by the Australian Education Union:

The remarkable expansion of the VET

“market” has taken place very quickly. Between 2008 and 2013, expenditure on

payments to non-TAFE (private) providers increased by $839.4 million, or 160

percent.[7]

3.20

At the Melbourne hearings on 2

September, Ms Pat Forward, Federal TAFE Secretary and Deputy Federal Secretary

of the AEU, advised the committee of updated figures showing the scale of

change in the sector:

So the market share, if you like, of

TAFE nationally in 2014 was 52 per cent down from 75 per cent in 2007. Private

provider share of government funded students has increased to 40 per cent up

from 15 per cent in 2007. This basically means that TAFE is perilously close

now to falling below 50 per cent of share nationally, but it also highlights

the rapid shift in the market and the unprecedented rates of growth in the

private sector. Private market share has increased by 159 per cent since 2007

and by 248 per cent since 2003...

In three states in Australia TAFE

market share has dropped below 50 per cent and in two of those states TAFE is

now a minority provider.[8]

3.21

This is in spite of declined spending

on vocational education – both public and private - as a sector,

Vocational education continues to be

the worst funded education sector with funding declining by 26 per cent since

2003. A recently released report by the Mitchell Institute confirms that VET is

surely the poor cousin of education sectors with spending on schools and higher

education far outstripping spending on vocational education and training

according to the authors of Expenditure on education and training in

Australia.[9]

3.22

Sector wide growth rates have been

mirrored by individual companies. Mr Patrick McKendry revealed that his

company, Careers Australia, had grown significantly in just four years - from

5,000 students in 2011 to 20,000 students in 2015:

Senator KIM CARR: That is an

extraordinary growth rate. Tell me where else does that occur in the education

system—a growth rate of what appears to be 400 per cent?

Mr McKendry: I am not sure it is something that is exclusive to Careers

Australia, I just do not know what the growth rates of other organisations have

been.[10]

3.23

These figures are extraordinarily similar

to that of publicly listed company, Australian Careers Network. Its June 30

financial report boasted that its student numbers had increased by 417 per cent

from 4990 students in 2014 to 25,784 students in 2015, with an "average

revenue yield per student" of $3,303.[11]

3.24

Figures for VET FEE-HELP payments show that

the growth in payments for some private companies has been dramatic. Careers

Australia has had payments increase from $3.539 million in 2011 to $108.172

million in 2014. Evocca College, trading as ACTE Pty Ltd grew from $1.831

million in 2011, to $24.958 million in 2012, to $131.25m in 2014.[12]

3.25

The business model employed by these providers

sees average fees charged to students – through VET FEE HELP – at

extraordinarily high levels. For example, while in 2013 the average VET

FEE-HELP loan was $10,621,[13]

the average tuition fee at Careers Australia was reported to be $18,276 in

2013. At Evocca College, it was $16,878 in 2013.[14]

3.26

By comparison, a student studying at a public university is liable for a

loan of between $6,152 and $10,266 in 2015.[15]

3.27

The committee heard evidence that some private

providers are making high profit margins on students and the Commonwealth. The

Workplace Relations Centre estimates that in 2013 Earnings Before Interest and

Tax (EBIT) margins were between 21 percent (for Vocation Limited) and 51

percent (for Australia Careers Network).[16]

3.28

Mr McKendry of Careers Australia revealed that

on average the profit margin of that company was 20 percent:

We generally operate and have operated

on the basis of about a 20 per cent margin across our business. We do not get

there all the time, but generally we believe that 20 per cent represents a fair

profit that enables us to keep reinvesting in the business.[17]

3.29

These companies also have an extraordinary dependence on revenue from

government sources. Mr McKendry of Careers Australia revealed the high dependence

of his business on government revenue:

Senator KIM CARR: How much of

your revenue actually comes from government sources?

Mr McKendry: It would have to be over 80 per cent. If I exclude

fee-for-service and international student income across the five or six states

and the federal government, it would be around 80 per cent.[18]

3.30

The annual report of Australian Careers Network also shows a high level

of dependency on government funding:

A significant proportion of the Company’s revenue is derived

from Government funding sources, including grant or subsidy programs.[19]

3.31

The Workplace Research Centre has estimated that up to 95 per cent of

revenue of the larger private providers may be dependent upon government

sources.[20]

This amounts to an extraordinary level of risk for investors to change in

government and policy settings in education more generally, and vocational

education more generally.

3.32

This has been demonstrated recently by two examples. One, the

extraordinary decline in the value of Vocation Limited following well

publicised regulatory issues in Victoria. Vocation’s share price which was $3

in early September 2014 fell to a low of 8c in September 2015.[21]

3.33

Another example of the damage that can be caused by exposure of poor

behaviour relates to ASX listed company Australian Careers Network (ACN). In

early September 2015 Fairfax media reported allegations of bad practices at

Phoenix Institute, owned by Australian Careers Network. Following these reports

ACN suffered a fall in its share price of 12 per cent.[22]

3.34

Ashley Services has suffered a similar fate after the cessation of the

Commonwealth Tools for Trade program following the 2014-2015 Budget. Ashley

listed on the Australian Securities Exchange in August 2014, after an initial

public offering priced at $1.66 a share. Following the latest profit downgrade,

the company’s share price fell to 38c, and is subject to a class action

lawsuit.[23]

3.35

As will be discussed later in this chapter and in this report, the

ownership structures of larger providers is opaque, the persons responsible for

the businesses is unclear and subcontracting arrangements further clouds

accountability.

3.36

It is hard to escape the conclusion that amongst larger private

providers, and indeed in some brokers, extraordinary profits are being made at

the expense of the taxpayer, and at the expense of students these providers

claim to be assisting. Such activities have heavily damaged the reputation of

the vocational education sector as a whole, and if left unchecked, could affect

Australia’s international education industry through reputational damage.

Misleading marketing of courses as

'free' or 'government-funded'

3.37

A number of submitters and witnesses raised concerns about the prominent

marketing of courses which attract VET-FEE-HELP support as being 'free' or 'government-funded'.[24]

Such language may serve to hide from students the fact that they are in reality

signing up for large loans from the government, with the expectation that these

loans will be repaid.

3.38

In addition, if students are unable to repay the loan because their

income never crosses the repayment threshold, they may have a debt against them

for the rest of their life. Once this consequence becomes clear to those

unaware when they signed up for the loan, the knowledge of it may also result

in a psychological burden on those already living with a limited income.

3.39

The Consumer Action Law Centre expressed concerns about this marketing

practice, noting:

'study now pay later' slogans that

fail to highlight the actual cost of study, and marketing VET FEE-HELP loans to

students who are unlikely to be able to repay their loans. These sorts of

slogans draw upon behavioural biases such as myopia and over-confidence, and

are more likely to result in students enrolling in courses that are

inappropriate to their needs.[25]

3.40

Several witnesses noted that the nature of the loan is further obscured

by the relative ease with which it can be applied for. For example, in its

submission, the Canterbury Bankstown Migrant Interagency explained how easily students

can obtain a VET FEE-HELP loan, without fully understanding the consequences of

what they are doing:

The common denominator is that consumers do not understand

what they are signing up for and are routinely unaware that they have in effect

taken out a loan for tens of thousands of dollars. The process for obtaining

consent and VET-FEE-HELP loans is in stark contrast to the stringent framework

of responsible lending obligations incumbent upon commercial creditors.

Clients have given us permission to see and keep record of

their 'Request for VET FEE-HELP assistance' form. Name, date of the birth and

Tax File Number are the only personal information that is required on the form;

and this very simple form is the ONLY mechanism which a student has to go

through to incur tens of thousands of dollars of VET FEE-HELP debt.[26]

3.41

Similarly, ACPET, the national industry association for private VET

providers, registered their concern over the lack of transparency for students applying

for VET Fee-Help loans about the extent of that loan:

On examination of the request for VET FEE HELP assistance

form, it was found that an applicant is not made aware of the VET tuition fees

loan amount they will be committing to as part of the application process.

ACPET recommends that such information should be made clear to the student to

as part of the loan application process to help inform the decision to assume

such a liability.[27]

3.42

In other cases, students were explicitly encouraged by the RTO or broker

to think of the loan required to undertake a course as one that they would

never have to repay, as in the following case study presented by the TAFE

Community Alliance:

An older woman in her early 70s was at the Bankstown Central

shopping centre having lunch with her bible group when they were approached by

a young man asking them if they would like a free laptop and a "free"

Diploma in Community Services. He assured them that though they had to sign up

for a government loan they would never have [to] repay it as they would need to

[earn] over $50,000 (and this was a group of pensioners) and they agreed they would

never be earning that much. The whole group signed up and got their laptops.[28]

3.43

Similarly, the Canterbury Bankstown Migrant Interagency reported:

In March 2014, a group of senior citizens from Bankstown (all

from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse background and little English) were

talked into enrolling in 'computer classes' with Unique International College

in Granville and Aspure College in Parramatta. It turned out that there was no

computer class and they were all enrolled in different diploma courses and

filled out forms to take out VET FEE-HELP. They were each offered a free

computer/ipad or $1000 cash by taking out the loan. They were told there no

need to come to class, but if they wish, they could come and free lunch will be

offered. They alleged in Aspire College, they had a canteen that could

accommodate a couple of hundred people and on the day it was packed with senior

citizens enjoying their free lunch.[29]

3.44

Providers prominently advertising that their courses are eligible for

VET FEE-HELP access for students is not, in and of itself, misleading. For many

students, VET would not be a viable option if they were not able to access VET

FEE-HELP. However, the ACTU notes that the option of paying late can lead to

students paying more for private a private course:

It is clear the concept of 'train now, pay later' is central

to attracting students – in some cases, to get them to sign up to courses five

times as expensive as the equivalent TAFE course.[30]

3.45

It was also argued that the process for students to keep track of their

VET FEE-HELP debt was overly complicated and did not incorporate warnings that

a debt was being accumulated. For example, in their evidence to the committee,

the Redfern Legal Centre noted the pitfalls of such a system, particularly for

those who do not regularly file tax returns.

3.46

In response to the committee's question about how students could obtain

information about their debt, the Redfern Legal Centre stated:

They have to make inquiries with the tax office. That is

really the only time that most of our clients will have any engagement with

that sort of information.[31]

3.47

It was noted by the committee that a considerable proportion of the

legal centre's clientele would not regularly be submitting a tax return. This

being the case, the Redfern Legal Centre suggested that it could be 'some years

before the full scope of the risk becomes clear'.[32]

3.48

The evidence received by the committee regarding the ease with which

some students are trapped into incurring VET FEE-HELP debts by the unscrupulous

practices of some RTOs is a matter of deep concern and suggests that further

strengthening of the regulations under which RTOs operate is a necessary step.

Inducement-based marketing

3.49

Although banned by the new Standards which came into effect in 2015,

numerous submitters noted the use of inducement-based marketing amongst private

VET providers.[33]

3.50

Of particular concern was the practice of offering students 'free' iPads

or laptops upon their enrolment. Notionally provided as a study aid,[34]

these devices featured heavily in some RTO's advertising, and would appear to

have been the deciding factor for some students in choosing to enrol in a

particular course or with a particular provider.

3.51

Mr Dwyer, solicitor for the Redfern Legal Centre, explained to the

committee the problem caused by the use of iPads and other such inducements in

private VET providers' marketing practices:

The particular issue of using a laptop or iPad as an

inducement was a critical one because vulnerable people were being told, 'Here

is a free laptop. All you have to do is sign on the dotted line.' They did not

have any understanding of the true cost of that.[35]

3.52

Ms Julie Skinner, a former tutor with Evocca College, expressed her

concerns about seeing this technique in practice in the college's marketing,

particularly as it focused on people for whom a 'free' computer or tablet would

be a significant drawcard:

I found the approach taken to recruit and screen students

inappropriate. Promotional stands were set up in shopping centres during

business hours, with iPads being the main promotional tool to attract students.

Disadvantaged, unemployed people appeared to be Evocca’s main target audience.

I’m sure many people signed up because they were delighted to

be getting a “free” iPad when in fact they didn’t really understand they were

signing up for a $20,000 iPad/debt.[36]

3.53

In discussing this issue, the Consumer Action Law Centre provided

evidence that it is aware of this practice and suggesting that it is another

marketing technique that helps to mask the fact that a VET FEE-HELP debt will

be incurred by the student:

We are also aware of private VET providers offering

incentives to consumers to study at their institution, for example offering 'free'

laptops or iPads. These incentives tend to detract from the fact that consumers

will incur significant VET FEE-HELP debts following the course census dates.[37]

3.54

The committee recognises that a ban on RTOs offering these inducements

was introduced in the 2015 Standards, but notes with concern the evidence

received from the Consumer Action Law Centre which suggested that this practice

has not been stamped out:

We hope these reforms will help to stamp out some of the most

unscrupulous practices that have resulted in complaints to our centre. However,

it is critical that these reforms are actively and publicly enforced by

relevant regulators. We have received a number of complaints about potential

breaches of the new laws including reports of door-to-door salespeople offering

free laptops and tablets. These complaints have been forwarded to the

department.[38]

3.55

While the new Standards explicitly forbid inducement-based marketing,

the committee notes that their introduction has not had the effect of

eliminating this behaviour by all RTOs. The committee therefore suggests that

more rigorous enforcement and tighter regulations around RTO marketing

practices are required.

High-pressure marketing techniques

and targeting of disadvantaged students

3.56

The committee heard from several witnesses who highlighted the marketing

techniques employed by some RTOs, or brokers on their behalf, which rely on

high-pressure tactics, and which often are targeted at vulnerable customers,

including those with English as a Second Language, Indigenous people, the unemployed

and those on Centrelink payments.[39]

3.57

The Redfern Legal Centre recounted their experience dealing with

disadvantaged students, targeted outside Centrelink offices or via door-to-door

selling in public housing blocks:

[W]e have a very vulnerable consumer base. They sometime find

the only way to get a door-to-door salesperson out of the apartment is to agree

to whatever is there. There are hard-sell techniques that encourage people to

sign up. They are told it is free and will not cost them anything. There is

also the instance of people being sold up for things like management courses

when they have absolutely no hope of doing that, and being told they have to do

more than they want to do. They want to do hairdressing and they are signed up

to managing a hairdressing salon. So there is a range of reasons. We have seen

it before in the maths tutoring programs and things like that that were sold

through shopping centres—that kind of technique. People want to engage, they

want to get trained, and they are signed up without any consideration of

whether that person could actually ever do that particular course.[40]

3.58

Similarly, the Consumer Action Law Centre expressed their concerns:

We are particularly concerned about VET providers and

education brokers that appear to target vulnerable consumers. These consumers

include Indigenous people, non-English speakers, unemployed people, and people

reliant on Centrelink income. We are deeply concerned about aggressive

marketing tactics that target consumers who do not have the aptitude or ability

to complete VET courses. When offering courses, we have seen providers and

brokers exaggerate the ongoing support available to students and reassure

computer illiterate consumers that they will be able to easily complete a

course online. We have received reports of education brokers in particular cold

calling or door-knocking potential students and pushing them to enrol in

unsuitable courses over the phone or on their doorstep.[41]

3.59

The Yarraville Community Centre, working with the Consumer Action Law

Centre, presented evidence to the committee that these tactics had continued to

be utilised by some RTOs even after the new Standards were brought into effect

early in 2015:

One of our largest programs at the centre is English as an

additional language and we have approximately 250 students studying at any one

time across eight different venues across the city of Maribyrnong. We work with

the most vulnerable and disadvantaged in our community.

In late April, one of our volunteers brought staff from the

Health Arts College into the centre during the teabreak and enrolled seven of

our students who were studying certificate I and II in English as an additional

language, which is very low level, into a diploma of business. They were told

to go to a particular chemist in Footscray and to take their passports, visa

and tax file numbers for certification. In one case, a taxi was provided by the

RTO to get there. The students were told the course was free. They were told

they would get an iPad or an iPhone for undertaking the course. Additionally,

they were told that if anyone asked them, to say they had enrolled in a diploma

in March. They attended the first class on Sunday, May 3.

The following week's class was cancelled and then the next

week they were all cold-called and advised they would have a debt. They were

told they would need not to worry about it as they would not have to pay unless

they earned more than $55,000 annually. They all requested to withdraw from the

course after attending one session.

The first time we were aware of this was when the students

came to staff visibly upset and showed us a letter stating that they had a VET

FEE-HELP debt of $13,200. The students all rang to withdraw from the course

between 12 and 18 May. They all received letters on 20 May outlining their debt

and the census date was 14 April, two weeks before they were enrolled. We then

called the community law action centre for advice to see if they were able to

help to get those debts removed and, fortunately, they have taken on the case

for these students. We have many more students who are being contacted by

phone, text, doorknocking and sometimes they are being harassed multiple times

to enrol in inappropriate higher diploma courses.[42]

3.60

The committee is particularly concerned that the introduction of new

Standards, designed in part to eliminate these unscrupulous tactics, has not

prevented some RTOs from targeting some of the most disadvantaged people in the

Australian community, as they were no doubt designed to do.

3.61

Another section of the community targeted by unscrupulous providers is

that of people with disabilities. Inclusion Australia, an advocacy group for

people with intellectual disability, criticised the approach of those VET

providers who:

prey on the vulnerability of youth with intellectual

disability to gain access to government VET funding in return for little, if

any, benefit to the student.[43]

3.62

Inclusion Australia provided evidence about a specialist disability

provider whose facilities had been targeted by such marketing practices:

We have spruikers for VET outside our building looking to

pick up youth with significant intellectual disability and sign them up for

very expensive and totally unachievable qualifications.[44]

3.63

This targeting of young people with disabilities by unscrupulous

providers causes numerous problems, according to Inclusion Australia:

Abuses of training programs including the offer of

inducements to sign up for unnecessary or inappropriate training is rife at the

moment — these waste taxpayers money, saddle people with disability with debt

they will never repay, do not contribute to employment that leads to economic

independence, and tarnishes the reputation of education, training and

employment programs.[45]

3.64

Women in Adult and Vocational Education (WAVE) also commented on this

practice, noting the affect it can have on women:

some of the aggressive marketing practices currently adopted

by private providers or their brokers, are targeted at women. For some women

who have not had previous opportunities to study for a career, the enticement

of a Diploma (and maybe the promise of a job) would appear very attractive, especially

if they were led to believe it would cost them nothing and could be achieved

over a matter of months. It is important that this type of marketing is stopped,

given the negative impact it will have on many women.[46]

3.65

Adult Learning Australia reported knowledge of private RTOs engaging in

high-pressure, inducement-based or targeted marketing practices in order to

increase enrolments:

Some of the behaviours reported by our members include:

Sales staff going door to door in public housing estates and spruiking

outside Centrelink offices and in outer suburban shopping malls frequented

by impoverished and socially marginalized people,

Offering impoverished and socially marginalized people iPads,

Coles Myer vouchers and other incentives for enrolment,

Offering cash bonuses to neighbourhood house staff or other community

workers in poor neighbourhoods for each learner they encourage to enrol,

Enrolling early school leavers with low literacy and numeracy

in high level courses with no literacy and numeracy support and limited or no

face to face class time,

Enrolling early school leavers with low literacy and numeracy

in multiple low quality courses.[47]

3.66

While not focused on disadvantaged students, the Victorian Automobile

Chamber of Commerce (VACC) reported that it was aware of private RTOs 'falsely

stating to VACC members that a particular qualification must be undertaken for

their trade due to legislative changes'.[48]

3.67

A related practice which gained some media attention was the practice of

some RTOs exploiting their links with job search websites to focus recruitment

efforts on the unemployed:

We are particularly concerned about the use of students'

personal information for direct marketing purposes. There have been reports in

the media of education brokers mining personal information from job

advertisements to identify job seekers and potential students. We have received

reports of details being harvested through the broker's own “free” job advertisement

website, without the job hunter's knowledge. It appears that clear and express consent

to use personal information for direct marketing purposes is not always being obtained

before contacting job seekers about courses. Job applicants are cold-called by course

sales representatives and subjected to high pressure sales tactics.[49]

3.68

Having received this wealth of evidence suggesting that high-pressure

marketing techniques continue to be used to entice vulnerable sections of the

community, the committee is of the view that it is appropriate to consider

whether steps are required to enforce the Standards.

Misrepresentation of likely

outcomes or qualifications received

3.69

Less prevalent a practice than those discussed so far, but worth noting,

is the practice raised by some submitters of potential students receiving

guarantees of employment after the completion of their course, for a specific,

often unrealistic, salary range. Additionally, the practice of potential

students being assured that their graduation from a particular course would

result in the appropriate qualifications to find employment in their chosen

field.

3.70

For example, in its submission, Speech Pathology Australia provided

evidence about this kind of marketing practice, noting that they were aware of

providers who used this approach.

At least one provider who is advertising the Certificate IV

in [Allied Health Assistant] course in a manner that implies that students will

be studying 'speech pathology' without any explanation that upon graduate they

will be competent to act as an AHA and will not be a 'speech pathologist'.[50]

3.71

This practice was also raised by ASQA in its review of RTO marketing

practices, noting that this type of advertising falls into the category of

'misleading or deceptive marketing and advertising'. Such advertising found by

ASQA in their review of RTO websites included statements such as '100% pass rate

and a guaranteed job'.[51]

3.72

It is concerning that students may be investing both time and money into

courses with the expectation of a particular financial and perhaps professional

return, which in reality they are unlikely to achieve. Such a practice may lead

not only to disappointment for students, but also to financial hardship, both

because of the debt incurred and because they may require more training to meet

their professional goals.

The role of brokers

3.73

The committee heard evidence about the role of third party marketing and

recruitment agents in recruiting students to the private VET sector, generally

referred to as brokers. The role of brokers is to market various courses or

providers to potential students, referring them to a provider. Brokers are generally

paid on commission for those students who enrol in a course.

3.74

While some witnesses described brokers as an inevitable consequence of

the competitive sector, there was considerable agreement about the need for

greater transparency and regulation of brokers to ensure a higher standard of

integrity in recruiting students to the private VET sector.

3.75

Mr Martin Powell, Victorian Executive Officer for ACPET, noted both

sides of the issue:

It is a sales force. It is better reach. They are mobilised

to get to parts of the market that providers have struggled with. In that

sense, that is a positive, but of course there needs to be integrity around the

information that potential students are provided with.[52]

3.76

This comment acknowledges that third party brokers are valuable to the

sector because they perform the essential sales function that helps private VET

providers meet their student goals and therefore continue to function as a

business. On the other hand, it also acknowledges the need to protect students

from those less scrupulous brokers who may not provide all or correct

information to prospective students.

3.77

The tightening of regulations around third-party brokers early in 2015 –

after many of the submissions to this inquiry had been received – was generally

seen as a necessary but not sufficient step in reframing the marketing

practices common in the VET sector.

3.78

Making this point, for instance, was Mr William Dwyer of the Redfern

Legal Centre, who commented favourably on the new Standards but noted that a significant

problem still remained:

Currently the standards and the regulations apply exclusively

to RTOs, but it is the conduct of the brokers and the marketing agents which

really leads to this whole mess in the first place. They are the ones with the

incentive to get high volume sales without any real focus on what happens after

that. I think at the moment they are causing a lot of the problems but without

much skin in the game. They can pass the buck and just keep generating their

commercial profits without much care for what happens to the individual

students afterwards.[53]

3.79

The lack of direct regulation over brokers was also noted by the TAFE

Community Alliance, who expressed their concern that the new Standards

introduced in 2015 apply only to the providers themselves, and not to brokers

working on their behalf:

Whilst ASQA and the Government refer to the new standards

that will more strictly control marketing and advertising, including that RTOs

cannot claim that students will get a job, the same regulations do not appear

to apply to brokers. The growth in the number of brokers, some involved in what

are unethical practices, including door-knocking in the western suburbs of

Sydney to persuade residents to sign up to courses with the enticement of free

iPads and the promise that there are no fees (due to being entitled to VET

FEE-HELP). It is not good enough for private providers to claim that they did

not know what was being claimed by the brokers they used.[54]

3.80

Noting this, the Consumer Action Law Centre drew attention to the

unclear responsibility regarding the regulation of brokers in the VET sector

and suggested that ASQA be empowered to act on this front:

It is not clear that ASQA has sufficient mechanisms to

respond to non-compliance by private VET providers and education brokers. As

such, in our view ASQA needs enhanced enforcement powers to ensure that ASQA

can respond swiftly in the event of noncompliance.[55]

3.81

ASQA themselves noted in their submission that the new Standards do not

directly regulate the actions of brokers and that further legislation may be

required if ASQA is to be able to address this problem:

While these new requirements go some way to addressing the

current concerns about the operations of brokers, it is not clear that such

measures will, on their own, effectively control unscrupulous brokers.

Significantly, the Assistant Minister for Educational and

Training, Senator the Hon Simon Birmingham, announced on 25 February 2015 that

legislation was being introduced to further crack down on unscrupulous VET

providers and improve training quality. The National Vocational Education and

Training Regulator Amendment Bill 2015 will, amongst other things, require

anyone, including brokers and other third parties, who is marketing a VET

course to clearly identify which RTO is providing the qualification.

Such an amendment to the NVETR Act, combined with the

strengthened new Standards will help respond where poor broker behaviour is

suspected and are welcomed by ASQA.[56]

The committee notes that currently, brokers are not regulated

directly, but only through making providers responsible for the actions of the

brokers they subcontract to. Greater and direct regulation of these agents is

required.

Recommendation 5

3.82

The committee recommends that urgent and concerted efforts are made to

further raise awareness of the rights of students and existing Standards

relating to providers in the VET sector. This effort should focus on advocacy

groups dealing with the most vulnerable members of the community, including the

long-term unemployed or disadvantaged, migrants and people with disabilities.

Recommendation 6

3.83

The committee recommends that the Department of Education and Training

and the Australian Skills Quality Authority conduct a concerted and urgent

blitz of all providers to ensure that they are consistently complying with the

national standards, especially those relating to student recruitment. This

blitz should be aimed at defending the interests of students, enforcing

adherence to AQF volume of learning standards and removing non-compliant RTOs

as VET FEE-HELP providers.

Recommendation 7

3.84

The committee recommends that the government, where there is evidence to

do so, provides a brief to the DPP to launch prosecutions against providers

engaged or benefiting from fraud and take steps to recover monies lost.

Recommendation 8

3.85

The committee recommends that the Australian Skills Quality Authority be

given powers to directly regulate brokers or marketing agents in the VET sector,

and to protect students.

Recommendation 9

3.86

The committee recommends that the government caps or otherwise regulates

the level of brokerage fees paid for VET FEE-HELP students to maximum amount of

15 percent the amount of the loan.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page