CHAPTER 4

Productivity

4.1

Along with a desire to adhere to the findings from the Cole Royal

Commission, the government has contended that the legislation is required on

economic grounds. The grounds provided as an example in the Explanatory

Memorandum are that during the period when the Australian Building and

Construction Commission (ABCC) existed,[1]

productivity in the building and construction industry improved, consumers were

better off and there was a 'significant reduction in days lost through industrial

action'.[2]

4.2

The impact of the ABCC on the productivity of the building and

construction industry has been a key theme in the evidence provided to the

committee. It is also an issue that has polarised submitters. Proponents of

the bill cited data that suggests productivity within the sector increased in

the periods between 2005 and 2012. In contrast, opponents pointed to:

inconsistencies in the productivity data for those years; discredited estimates

based on flawed assumptions used in economic modelling; and fallacious findings

that mistake correlation for causation.

4.3

The centre of this controversy is a report commissioned in 2007 by the

ABCC and drafted by Econtech Pty Ltd (now trading as Independent Economics),

(the Report). The Report has been updated several times since 2007, with an

update commissioned by the ABCC in 2008, and further updates commissioned by

Master Builders Australia in 2009, 2010, 2012 and 2013.[3]

4.4

The Report considers the impact of industry specific regulation on

building and construction industry productivity. The versions of the Report up

to 2012 assessed whether the Building Industry Taskforce and the ABCC had a

significant impact on building industry productivity, while the 2013 Report

also considered the effect of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate that

succeeded the ABCC.

4.5

Independent Economics make a number of key claims in their reports. The

central claim is that building industry productivity has outperformed

productivity in the rest of the economy during the period up to 2012 and the

major contributory factor in this finding was the presence of the ABCC.

Independent Economics Methodology

4.6

The Report compares productivity data for the periods before the

Building Industry Taskforce was established in 2002; the period from 2002 to

2012 when the Taskforce and then the ABCC were in operation; and then finally

the period from mid-2012 when the ABCC was replaced by the Fair Work Building

Industry Inspectorate (FWBII).

4.7

In explaining the methodology used in the Report, Independent Economics

initially say three types of productivity indicators are used to 'determine the

extent of any shifts in industry productivity from changes in industry

regulation between regulatory regimes.'[4]

According to the Report these indicators are:

- Year-to-year comparisons of construction industry productivity are made using data from the

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), the Productivity

Commission

(PC)

and academic research.

- The difference in costs in the commercial construction and those in the

housing construction sector. Rawlinsons data[5] is used to compare the

timing of any changes in this cost gap with

the timing of the three regulatory regimes.

- Case studies of individual projects, undertaken for earlier reports by Econtech Pty Ltd and by

other researchers, are used to provide comparative information on productivity performance

between the

three regulatory regimes.[6]

4.8

However in the section: Productivity comparisons in the building and

construction industry, Independent Economics add a fourth productivity

indicator to their analysis, the number of days lost to industrial action.[7]

Critiques of Independent Economics' Report

4.9

The findings of Independent Economics have been challenged by a number

of stakeholders and experts over the years. The committee received evidence

that discredits the Report by analysing the assumptions and methodology used by

Independent Economics. The figure of 9.4 per cent productivity gain is central

to the findings of the reports, and arguably the entire economic case for

re-establishing the ABCC. The data used to establish that figure was challenged

by a number of submitters.

4.10

Professor David Peetz, from Griffith Business School, the ACTU, and most

recently the Productivity Commission, systematically question each element of

the Report and the figures and assumptions that are fed into the Independent

Economics' Computable General Model (CGE) model that finds the existence of the

ABCC was responsible for substantial gains to the economy as a whole.

Year-to-year comparisons

4.11

The report uses a number of figures when discussing the year-to-year

comparisons of construction industry productivity. The first is the 21.1 per

cent over performance against predictions 'based on historical performance

relative to other industries'.[8]

4.12

The ACTU submission and evidence before the committee addressed what it

claims is spurious methodology. The ACTU contends that the predictions the

reported gains are measured against have been derived from a 'deeply flawed'

methodology using a regression model. While the methodology used is not

explicit in the Independent Economics report, ACTU has come up with a model

that generated identical findings in relation to the construction industry.[9]

ACTU explained how the model works:

The model used to generate

the 'predicted

productivity' line

is

not made

explicit in the

report...The report's approach appears to be to

estimate a regression model using data for the period 1985-86 to 2001-02, with the level of construction

industry productivity as the dependent variable and the level of productivity for the total economy as the

explanatory variable.

Independent Economics use the estimated coefficients from this regression to calculate what the level of labour productivity in the construction industry would have been in each year in the ABCC period if the relationship between construction productivity and total economy productivity had remained unchanged from the earlier period...It compares

this to the actual level of labour productivity in the industry. The difference between the two lines is

ascribed to the influence of the ABCC.

The approach is deeply

flawed. Construction industry productivity grew faster,

relative to the all industries average, in the ABCC period than it had done in the earlier period not because construction industry productivity grew particularly rapidly, but because

the

all industries average growth rate fell.[10]

4.13

The ACTU then applied the methodology to other industries and found that

other industries also 'over performed':

If you replicate that same methodology for a range of other

industries—in fact, the majority of industries—you will find a, so-called,

overperformance of much the same sort in a whole range of industries like

agriculture, retail, accommodation and food, that have nothing to do,

whatsoever, with the ABCC.[11]

4.14

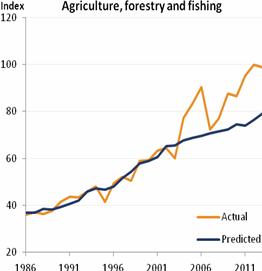

The ACTU provide a number of graphs to illustrate their findings:

Source: Actual

productivity growth figures from ABS 5204, table 15. 'Predicted' productivity growth figures based on estimation of the model LPi,t = a + �LPtotal,t + et for each industry 'i', using data for the period 1985-86 to 2001-02, as per Equation 1.[12]

4.15

If the Independent Economics' assumption that the ABCC caused the

overperformance of the construction industry, then according to the ACTU, it

must have equally caused the overperformance in the other eight industries that

saw productivity gains against predictions.

For it to be accepted that the outperformance of the construction industry is due to the ABCC, it must be

accepted either:

-

that the ABCC exerted an influence on productivity

in

a range of industries other than construction; or

-

that some economy-wide factor like mining

affected the relationship between predicted and actual productivity in all industries

other than construction; or

-

that the ABCC

lifted productivity in construction while some other factor served to lift productivity relative to its predicted level in a majority of other industries at exactly the same time while not affecting construction.[13]

4.16

Professor Peetz was also sceptical of the argument that there is a

causal relationship between the construction sector and the rest of the economy

to the extent that productivity could be predicted:

There is no particular reason

to presume that one can accurately predict

what productivity will be in the construction sector on the basis of what productivity is in the rest of the economy. Moreover, according to Econtech, construction

industry productivity

began to rise above its ‘predicted’ level

back in 1997. By 1999, three years before even the Building Industry Task Force,

construction industry productivity was exceeding

Econtech’s ‘predictions’ by almost as much

as in 2007, making the claim of a ‘reform’

effect unwarranted.[14]

4.17

Professor Peetz continues the critique of the approach taken by

Independent Economics when considering another year-to-year comparison figure

used.

4.18

As discussed earlier the Report found that 'construction industry multifactor productivity

accelerated to rise by 16.8 per cent in the ten years to 2011/12.'[15]

According to Professor Peetz the 16.8 per cent differential between the market

sector and the construction sector was heavily influenced by 'the large decline

in productivity in mining and resources'. Furthermore Professor Peetz points

out that construction multifactor productivity through the period when the ABCC

was in existence, was 'pretty much in the middle amongst industries.'[16]

4.19

Similar to ACTU, Professor Peetz accuses Independent Economics of

repeatedly seeking to 'find causality when none might be due'.[17]

The difference in costs between

commercial and housing construction sectors

4.20

Independent Economics' next indicator is the gap between the domestic

and commercial construction sectors. In the 2007 version of the Report this is

the indicator that provided the 9.4 per cent productivity gain that has

remarkably been found using this indicator on its own, as well as a being found

using this and a combination of other indicators.

4.21

As discussed earlier in this report the reasoning used in the

Independent Economics' Report is that commercial construction sites are more

likely to be subject to 'industrial disputes' and 'poorer work practices', in

contrast to the domestic sector which is more 'flexible'.[18]

4.22

This is not the first time the assumption that a unionised workforce is

the cause of differences in building costs between the two sectors has been

subject to critique. The early Econtech reports of 2003 and 2007 were

criticised for using this method because they discounted other factors in

explaining the gap. According to a paper in the Journal of Industrial

Relations by Cameron Allan and others:

Other structural factors could also explain them, including

greater on-site complexity (it costs more to affix a plasterboard wall on the

10th floor of a high rise than on a ground floor cottage), higher capital

intensity and higher profit margins in the commercial sector.[19]

The Domestic housing is not a model

industry

4.23

The Report cites the productivity of the domestic housing sector as

being something the commercial sector should aspire to. However recent reports

from the Fair Work Ombudsman's audit program show the terms and conditions of

people working in the industry are routinely and comprehensively undermined by

employers. These contraventions include non-compliance with hourly rates of

pay, allowances, record-keeping and play slip obligations.

4.24

The figures were particularly damning for the apprentices in the

domestic building industry. As the audit report highlights, 'Apprentices are

usually young workers, in their first job and may be unaware of their rights.'[20]

The audit of the 164 employers in Victoria showed that only 6.1 per cent of

employers were compliant with regard to the pay, terms and conditions of their

apprentices.[21]

The table below[22]

illustrates the areas that employers did not meet their legal obligations:

4.25

Of the 164 employers, 154 were found to be in contravention:

-

60 (39%) had monetary contraventions

-

60 (39%) had record-keeping contraventions

-

34 (22%) had both monetary and non-monetary contraventions

The audit recovered $192 793.01 for 121 employees.[23]

4.26

Figures from the Tasmanian domestic building audit show similar

non-compliance across the sector, again in relation to the most vulnerable

employees, apprentices. The audit found that of the 150 employers audited, 60

per cent were in contravention of legally binding awards and conditions for

apprentices. The chart below[24]

shows where those contraventions occurred:

The audit recovered $116 000

for 86 employees.

4.27

A similar audit of the domestic building sectors in SA/NT and WA also

showed extensive contraventions. In SA, 49 audits found 31 employers in

contravention; in NT, 17 audits found 5 in contravention; in WA, 76 audits

found 42 employers in contravention. The table below[25]

breaks down the types of contraventions:

The audits recovered $67 000 for 76 employees.[26]

4.28

The figures show that there is what could be described as a culture of

non-compliance in the domestic housing sector in relation to the proper payment

of awards and conditions of apprentices. The Victorian figures are startling

in that 93.9 per cent of employers are acting outside the law. The other

audits reveal this is endemic in other states as well.

Individual Projects

4.29

The use of case studies as one of the elements that informs the figure

of 9.4 per cent productivity gain has also attracted criticism. Many of the

studies were undertaken as part of the 2007 Report and include claims that

'industry participants have also found that improved workplace practices have

contributed to cost savings for major projects'.[27]

4.30

The difficulty with the use of case studies is that the results cannot

be objectively measured for validity and cannot be said to be representative of

industry-wide practice. Professor Peetz criticised case studies as not being a

sound methodology because much of the data is unverifiable:

Case studies

lend themselves strongly to cherry‐picking of data, as – unlike with analyses of, say, ABS data where others can obtain access

to the data and attempt

to verify results

– the full data in case

studies collected are typically not revealed, rather only those selected

by the writer are

revealed. If cherry-‐picking is observed in the use of quantitative data, then there is little reason to believe it has not occurred in the use of qualitative data.[28]

4.31

Allen and others in their Construction Industry Productivity in

Australia paper have specific concerns over the case studies used by

Independent Economics, and the data that confuses working days lost to

industrial action with productivity:

The ‘case studies’ (which were identical in the 2007

and 2008 reports) comprised one undertaken by the Institute

of Public Affairs,

a conservative lobbyist and ‘think tank’ (Murray, 2004), and two

by Econtech, which boiled down to the qualitative claims of two leading construction companies and data on

reduced working days lost due to industrial action, supported in 2009 by extracts from three submissions by advocates of coercive powers. Here and elsewhere, Econtech appeared to confuse reduced

industrial action with higher

labour productivity. Labour productivity is the amount of real output per unit

of labour input (such as the number

of houses built per hour

worked). Strikes normally mean no output is produced during a period in which no labour is

used or paid for, and so have no direct

relationship with output

per unit of labour

input. If reduced

industrial action has led to increased productivity, this should be visible

in the productivity data.[29]

4.32

A further example of cherry-picking and the flawed assumptions of the

Econtech reports, the 2008 report in particular, lies in its reliance on a

pamphlet authored by Ken Phillips for the Institute of Public Affairs in 2006[30]

which Econtech claims, 'support the findings from the other subsections (of the

Econtech report) that the existence of the ABCC and the supporting regulatory

framework has led to significant improvements in productivity.'[31]

4.33

The pamphlet purported to analyse the impact of industrial relations on

the cost and timeliness of one of Victoria’s largest ever civil construction

projects, the EastLink Tollway. The purpose of the paper appears to be a

justification for the operation of both the former ABCC and the WorkChoices

industrial relations regime. In doing this, the paper seeks to draw a

comparison between the cost and timeliness of the WorkChoices/ABCC era EastLink

project with the pre-WorkChoices/ABCC CityLink project.

4.34

The paper employs a highly speculative series of 'assumptions', 'estimates',

'expectations', 'likelihoods' and 'probabilities' to arrive at 'estimated', 'probable'

and 'likely' total additional costs to EastLink, 'assuming continuous

construction' of 'likely' to be $295 million.[32]

4.35

In order to estimate the differential cost advantage to Eastlink over

CityLink, the author sets out what he claims are 'probable' excessive labour

costs that would have been incurred by the EastLink project but for the

existence of the ABCC and Work Choices. Among these probable additional costs

are what the author deems 'unproductive days'. All of them include basic

conditions such as annual leave, statutory public holidays (including Christmas

Day) and rostered days off which for the uninitiated are days off in lieu of

additional hours worked during the ordinary hours of work.

4.36

Phillips claimed that since EastLink could be subject to an industrial

relations regime that would allow a 'theoretical' 365 days per year

construction schedule its cost advantage over CityLink could be $184 million on

labour costs alone.[33]

4.37

The author states that '[i]t is not clear if the Eastlink industrial

undertakings require non-working union delegates' but that didn’t stop him

claiming that they cost '$5 million plus',[34]

a figure which inexplicably blows out in the table on the following page to

$58.5 million.[35]

Committee View

4.38

The author also makes up figures of $9.2 million for 'assumed'

industrial action over renegotiation of industrial agreements that didn’t

happen and $43.3 million for occupational health and safety stoppages that

never occurred. For good measure he adds the cost of 'sham weather disputes'

that didn’t happen that 'would add an unknown amount in overheads' and yet the

author was still able to give a 'likely' cost of $31 million.[36]

4.39

Reinforcing the vague, imprecise and speculative additional cost

estimates arrived at by the author, he concludes by saying that his 'posited'

figure of $295 million 'could be too high or low, but ... is likely to be

conservative.'[37]

It could also be a fantasy.

4.40

It is the Committee’s view that the adoption by Econtech of these

assumptions further diminishes the value of Econtech’s analysis of productivity

in the building and construction industry.

Days lost to industrial action

4.41

Independent Economics contends that the unwinding of the gains

established through the years of the ABCC is illustrated by the number of days

lost through industrial action. The figures used show the actual days lost

from financial years 1995/96 through to the third quarter of the financial year

2012/13, and incorporates an 'estimate for the June quarter of 2013 [that] has

been made by assuming that the growth rate for the full financial year is the

same as the growth rate in the first three quarters of the financial year'.[38]

The Report concludes that:

...more than one half of the improvement in lost working days

achieved in the first five years of the Taskforce/ABCC era has already been

relinquished in the first year of the FWBC era. In fact, in 2012/13, the

working days lost in construction was the highest since 2004/05.[39]

...

This sharp increase in work days lost to industrial disputes

in only the first year of operation of the FWBC is consistent with the expected

reversal of the productivity benefits achieved during the Taskforce/ABCC era.[40]

4.42

Master Builders attempt to quantify the cost of the days lost due to

industrial action, and although they concede it is not possible to cost the

impact on each project. They roll together a number of assumptions of

potential costs to come to their figure:

While it is not possible to accurately calculate the

construction cost of a day lost[...] If it is assumed that the direct cost of a

strike is $100,000 per day then 89,000 days lost to industrial action would

equate to $8.9 billion.[41]

4.43

Other submitters argued the assumptions made by the Report do not

support the claims that the number of days lost since the ABCC was abolished is

evidence 'consistent with the expected reversal of the productivity benefits

achieved during the Taskforce/ABCC era'. Firstly, there is the problem with

conflating industrial days lost with labour productivity figures discussed in

the previous section. The second substantive criticism is that the figures do

not actually support the argument put forward in the Report.

4.44

Professor Peetz calls the use of the estimate of the final quarter as

'wildly erroneous'. What the figures actually show when the final data was

available was that the number of days lost was actually 61,600, and not the

estimated 89,000. Professor Peetz also quotes figures from the last 12 months

that data that show that there was a slight reduction in that 12 months from

the last 12 months of the ABCC. This supports Professor Peetz's proposition

that:

The reality is that disputation data vary substantially from one

quarter to the next, and Econtech conveniently overlooked this fact when attempting to justify a major deterioration of construction industrial relations under the FWBC.[42]

4.45

The ACTU supported the argument that days lost due to industrial action

since the abolition of the ABCC infers a trend that the number will rise

through industrial disputes:

During the ABCC's operation, there was an average of 9.5 working days lost to disputes per 1000 employees per quarter in the construction industry. In the four quarters after the abolition of the ABCC, the rate of disputation in the industry has been below the ABCC-era average twice (in December 2012 and

June 2013) and above it twice (in September 2012 and March 2013).[43]

4.46

In evidence to the Legislation Committee in November the ACTU also

suggested that each dispute in the industry had the capacity to severely alter

the figures because of the low number of disputes in the industry, and indeed

across the whole economy:

[I]n this industry, in fact, as in all others when you look

at the industrial action statistics, the overall level of industrial

disputation in our economy is so low—so low—that a very small number of

disputes can cause a spike in the graph. Because the incidence of industrial

disputes is orders of magnitude lower even than it was under early iterations

of Howard government industrial law, one or two disputes move the needle.[44]

4.47

To add further weight to this argument the latest quarterly figures on

days lost per employee due to industrial action was the second lowest since

1985 and the lowest since 2008 when the ABCC was in operation.[45]

4.48

The other point made during the inquiry in relation to days lost was

whether they were as a result of lawful or unlawful industrial action. As far

as the committee understands, the ABS figures from any period do not

disaggregate the figures by days lost through protected and unprotected

industrial action.

Productivity Commission assessment

construction productivity

4.49

The long list of stakeholders unconvinced of the figures and conclusions

of the Report now includes the Productivity Commission (the Commission). In

its draft report on public infrastructure the Commission expresses doubt on the

claimed productivity growth rates that Master Builders Australia rely on

through their commissioned report from Independent Economics.

4.50

The Commission agreed on the importance of the Report to the debate on

economic implications of changes to industrial relations in the construction

industry:

The series of studies

have been highly influential in

debates about the effectiveness of the ABCC on construction productivity, and by inference, relevant

to various conjectures about the degree

to which diminished union power affects productivity at the macro level. Most umbrella groups

representing construction and other businesses have highlighted the studies

and claimed that they are valid...

The validity and interpretation of these studies are therefore key issues.[46]

4.51

The Commission noted that the Report was two-pronged in its approach to

measuring productivity. The first uses historical data to predict growth and

then measures that against actual growth. The Commission then notes that the

model's appropriateness cannot be measured because 'no statistical model (or

specification tests of that model) was provided', and that the 'likelihood of

misspecification is high'. The Commission concludes that 'As it stands, IE’s

predictive model should be given little weight'.[47]

4.52

The second modelling approach used in the Report was the measurement of

the domestic versus commercial costs discussed earlier in this chapter. The

Commission considered the premises of the argument and the conclusions reached

by Independent Economics and make the following comments:

First, no judgment can be made about the effects of the FWBC from the data

currently available. There is only one year of data and the conclusion ignores the

fact

that, even during the ABCC period, relative costs sometimes rose.

Second, over a longer period, the link between the IR regimes

and productivity is not robust.

Third, even if the IE numbers were robust, concluding that IR

is the exclusive factor explaining the trend fails to consider a range of rival

explanations and considerations.[48]

4.53

The Commission concludes its analysis by stating that Independent

Economics' results are neither reliable nor convincing indicators of the impact

of the BIT/ABCC', and cites the views of major business consultants who have

also expressed doubts about the findings:

Major business consulting firms have expressed doubts as well

(ACG 2013; PwC 2013a, p. 8). For example, Allen Consulting argued in a report

to the Business Council of Australia:

It

is not feasible to link the size of the productivity shock to definitive

evidence of recent performance. Events that have given rise to concerns about

industrial relations unrest are too recent to appear in economic statistics.

(ACG 2013, p. 39) [49]

Committee View

4.54

The report from Independent Economics is pivotal in the debate over the

purpose and effectiveness of the ABCC and the FWBC regime that replaced it.

Almost every single argument by proponents of the legislation travels through

this prism to arrive at conclusions and ultimately recommendations for action,

based on the impact that the ABCC had on the productivity of the building and

construction industry. The difficulty the Committee has with this approach is

that the evidence suggests the methodology and assumptions used by Independent

Economics throughout its series of reports are at best, not robust.

4.55

The Committee is deeply concerned that the fundamental figure of 9.4 per

cent productivity gain, initially arrived at through a flawed analysis of the

gap between residential and commercial construction only, is regurgitated in

all of the reports since. The Committee does not find that reaching this figure

afresh each year is plausible, despite the calculations being based on more

variables and updated data.

4.56

The second fundamental flaw in the Report is that it does not prove any

productivity gains are as a direct result of the existence of the ABCC. The

evidence received throughout the inquiry raised a number of economic and

administrative factors that could and do impact the economic performance of any

sector of the economy. The report discounts all of these in favour of the view

the ABCC alone is responsible for the productivity growth. Again the Committee

does not find this conclusion plausible.

4.57

The committee is highly sceptical of the findings of the Report, and the

methodology used by Independent Economics. The report appears to continually

'beg the question' it sets out to answer, confuses correlation for causation,

and repeatedly relies on estimates based on spurious assumptions.

4.58

The Wilcox Review found that the 2007 Report is 'deeply flawed', and

'ought to be totally disregarded'.[50]

This was after Econtech, as they were then trading, had had the opportunity to

respond to the criticisms put to them by Justice Wilcox. In 2014, the

Productivity Commission finds it neither reliable, nor convincing. The list of

other detractors comes from across the political spectrum, and includes

academics, unions and major business consultancies. The Report, its

methodology, and its conclusions should be disregarded in its entirety.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page