Dissenting report by Liberal Senators

Introduction

Liberal senators acknowledge that the abuse of alcohol,

especially by the young, is a major social, health and economic challenge

confronting all Australians. Accordingly governments at all levels must be

prepared for tough, comprehensive measures to address this challenge and to

empower communities and individuals to wind back what witnesses called the

“write-off culture” of drinking in our society. As the community’s focus on

this issue sharpens, it is critical that government set an example of good

policy setting and evidence-based action. Initiatives which are poorly thought

through, which appear opportunistic or which alienate the very cohorts whose

behaviour they are designed to modify are likely to fail. Public cynicism

about the motives of governments, particularly where measures involve the

raising of taxes, can seriously undermine the objectives these measures pursue.

The increase in the tax rate applying to ready-to-drink

alcohol beverages (RTDs) will impose a $3.1 billion tax burden on Australian

consumers. Even assuming positive health implications from this increase, there

are certainly potential downsides in terms of employment in the alcohol and

hospitality industries, unanticipated deleterious behavioural changes by those

who abuse alcohol and greater financial pressures on those who consume alcohol

responsibly.

For this reason Liberal senators believe that an onus

must fall on the Federal Government’s shoulders to demonstrate that a step of

this magnitude is likely to achieve overall positive outcomes in the fight

against alcohol abuse. We reject the notion that “doing something” about

alcohol abuse is a sufficient justification for a measure which carries such

serious potential downsides as does this excise increase. Evidence of a net

benefit should be clear and unambiguous.

Liberal senators however believe that the evidence before

the inquiry was indeed ambiguous. On the test suggested above, therefore, since

the evidence is not conclusive or clear, the case for the tax is not made out.

Further, much of the support for the tax from the public

health sector was conditional on the Government implementing a broad suite of

policies relating to alcohol, a suite which it is clear does not presently

exist and the resourcing for which has not yet been allocated.

In this dissenting report we outline a number of areas where

the case supporting the tax is either weak or at best marginal.

Lack of evidence that consumption is increasing

One of the key points made by

the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) on their analysis of the

National Drug Strategy Household Survey data was that the overall drinking

status of the Australian population has been stable over the past two decades

(see Table 1 below).

Table 1–Alcohol Drinking Status: proportion of the

population aged 14 years or older, Australia, 1991 to 2007. [1]

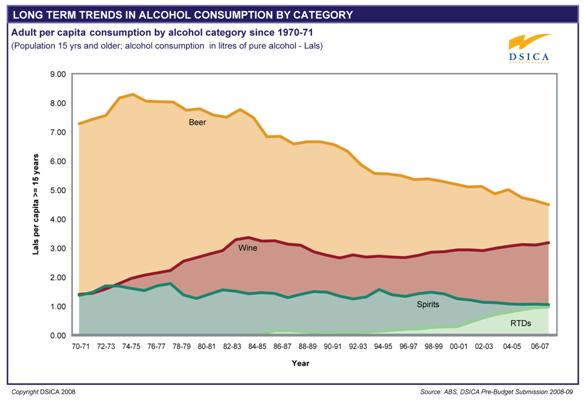

In support of this finding the Distilled Spirits Industry

Council of Australia (DSICA) made the following points:

- Australia's per capita global alcohol consumption ranking has

been falling;

- On a per capita basis, alcohol consumption in Australia has

fallen by over 20 per cent since a 30 year peak reached in the early 1980s; and

- Alcohol consumption on a per capital basis has not increased

significantly since the tax reforms in 2000 which included the tax on RTDs.[2]

DSICA provided a table

to demonstrate that the growth in popularity of RTDs must be set against a

decline in overall alcohol consumption (see Figure1).

Independent Distillers Australia (IDA) also

commented that:

It is important to note that drinking at risky levels has been

decreasing over the last six years as measured by the Government's own

statistics, including among young females.[3]

Figure 1: Australia's adult per capita

alcohol consumption by alcohol category (1971-71 to 2006-07)

Source: Submission No. 27 (Distilled Spirits Industry Council

of Australia), p.69.

Mr Terry Mott, Chief Executive Officer, Australian Liquor Stores

Association (ALSA) pointed out that:

It appears from evidence from the Australian Institute of Health

and Welfare, the ABS and the New South Wales Department of Health’s secondary

schools survey that there does not appear to be a significant, growing problem

with youth drinking, and that information does not seem to have been contested.

ALSA does not for a minute shy away from the fact that there may be young

people misusing alcohol, but it does not appear to be an endemic, growing

problem. Even if there were an epidemic of teenage binge drinking, we are not

of the belief that taxation, as a blunt instrument, will give any real solution

to solve that sort of problem.[4]

Mr Daryl Smeaton, Chief Executive, Alcohol Education and

Rehabilitation (AER) Foundation, told the Committee that a comprehensive

approach was needed as:

...clearly our biggest drinkers are not teenagers; they are the

20- to 30-year-olds.[5]

Mr Smeaton further noted:

We have focused this particular issue around young women but

excessive consumption is a problem across a very broad range. It is not just

young women.[6]

While none of this constitutes a reason for inaction on

excessive drinking, it does suggest that a rushed or under-researched response

to this problem is not warranted. The anecdotal evidence of a surge in

dangerous drinking offered by some witnesses to the inquiry needs to be set

against the less emphatic data available from bodies such as AIHW.

The ‘link’ between RTDs and risky alcohol use

The AIHW noted the preference for RTDs has increased slightly

over the period 2001–2007, particularly in older age groups, but the trend

among those aged under 18 years is unclear (see Table 2 and Table 3).

The AIHW also found that there has been virtually no change in

the pattern of risky drinking over the period 2001–2007, including among young

Australians.[7]

Given these findings the AIHW concluded that 'given the stable

prevalence of risky drinking, and the lack of any clear trend regarding

preferences for RTDs, the increased availability of RTDs does not appear to

have directly contributed to an increase in risky alcohol consumption'.[8]

IDA pointed out that the Government has publicly relied on the

findings from the National Drug Strategy Household Survey to justify the excise

increase saying the figures showed an 'explosion' of binge drinking among

teenage girls. They noted:

The Government has misinterpreted the findings of this report

and mistakenly endeavoured to correlate growth in popularity of RTDs with binge

drinking. We are yet to see any evidence to support this assertion. [9]

Table

2–Trends in preferences for specific alcoholic drinks, 2002–2007, males (per

cent)[10]

Table 3–Trends in preferences

for specific alcoholic drinks, 2002–2007, females (per cent)[11]

Mr Douglas McKay, Executive Chairman, Independent Distillers

Australia told the Committee:

RTDs have been part of the national alcohol landscape for 40

years in Australia. Unarguably, the convenience and other benefits of RTDs have

helped augment their popularity. But this increasing popularity does not

necessarily mean increasing alcohol abuse and the two things seem confused in

much of this debate. RTDs are a minority part of the liquor industry and there

is no compelling evidence linking them to an increase in alcohol abuse. Levels

of risky drinking remain largely unchanged or slightly down according to the

most comprehensive and long-running research by the AIHW.[12]

Mr Terry Mott, Chief Executive Officer, ALSA also questioned

the link that has been drawn between RTDs and alcohol abuse as:

A tenuous interpretation of the statistics, as they fail to

compare what young people may have been consuming and mixing for themselves in

earlier statistics....it does seem a long bow to draw to suggest that, even if

there were a significant trend in alcohol misuse, that is has been caused by a

particular product or category.[13]

Liberal senators assume that if RTDs are indeed a ‘Trojan

horse’ to young Australians, ushering them into higher or more dangerous levels

of alcohol use than before, there would be evidence of increased rates of

overall drinking in these age groups. There is no such evidence. The evidence

is consistent with this generation of young drinkers having switched to RTDs

from, say, the beer or sparkling wine preferences of earlier generations, but

not at overall greater consumption levels than their predecessors.

Were health considerations uppermost in the Government’s mind?

Liberal senators note the lack of a submission from Treasury to

the inquiry despite the modelling being included specifically in the terms of

reference at (g). Questioning of Treasury officials during Estimates revealed

their task was only to estimate the impact on the budget of the measure using a

range of studies of the price elasticity demand for alcohol.[14]

Treasury officials also commented on the involvement of Health:

Senator COLBECK—Mr Ray, you said before that you

did not speak to the Department of Health in relation to this. Why would you

not talk to the agency that has all the figures in relation to this matter?

Mr Ray—With respect to my colleagues in the department of

health, they did not have the data that we needed in order to do the costing.

Senator COLBECK—What data was that?

Mr Ray—As I explained earlier, it is ATO data on

clearances.[15]

IDA argued that the Government's revenue and health policy

objectives will not be achieved.

The Government's economic modelling to support the tax increase

is not based on solid research – Treasury themselves acknowledge broad

assumptions have been made in formulating their revenue projections.[16]

IDA further commented that sales data since the excise increase

calls the modelling by Treasury into question:

Treasury estimated that RTD volume would decline by 4%. Current

sales trends, however, indicate that Treasury estimates of the revenue from the

new tax could be overstated by a much as 40%.[17]

Mr Warwick Ryan, Director, Government relations, KPMG told the

Committee:

But certainly sales of 375 ml and 200 ml containers of

full-strength spirits have gone up about 20 per cent since the tax increase.

Certainly the zero cross-price elasticity assumption which Treasury used in

their modelling is not a number that has been applied in overseas countries and

it is not the cross-price elasticity or the transference factor which you refer

to that will be used in the modelling undertaken for DSICA. Certainly the

evidence in the market of substitution of full-strength spirits, beer and wine

shows that that zero transference factor is not credible.[18]

Liberal senators note with concern that Health was not a party

to the cabinet submission which approved the RTD excise increase. We conclude

from this extraordinary omission that the Government’s chief objective was

revenue-specific, not health-specific.

Revenue windfall not matched by investment

in prevention/education strategies

Treasury modelling showed the financial implications of the

increase in excise for RTDs. The total revenue increased from $97.9 million in

2007-08 to $892.6 million in 2011-12.[19]

By contrast, the Prime Minister’s National Binge Drinking Strategy has a budget

of just $53 million.

IDA noted that none of the revenue will go to the National

Binge Drinking Strategy:

The Budget shows the RTD tax changes are expected to raise $3.1

billion. Despite the increased revenue from the excise increase, Budget papers

reveal the National Binge Drinking Strategy will not receive any of this.

Instead, 2008-09 Budget Papers say the Strategy will be 'met from within the

existing resourcing of the Department of Health and Ageing'.[20]

IDA further noted the lack of clarification regarding the use

of the revenue:

Minister Roxon has said that a proportion of the $3.1 billion

revenue will be directed to general preventative health programs. The

Government has not outlined how much constitutes a 'proportion' or if alcohol

strategies or programs will benefit.[21]

Mr Smeaton, AER noted:

You asked me what my understanding was. As I have said, the

government have said on a number of occasions that some of the revenue from

this particular increase in taxation will be directed back to preventative

health. I have not sought, nor have they offered, an amount. There is a National

Preventative Health Strategy task force working on these issues, and it is due

to report, I think, initially by the end of this year. I expect that some of

the recommendations will need funding and some of those things will be funded,

I expect, from that revenue stream.[22]

The Government appears at this point to be putting virtually

all its eggs in the tax increase basket, despite the strong urgings of public

health groups that a multi-faceted approach is required. Liberal senators can

understand why Australians would be cynically attracted to the view that

revenue is the Government’s primary motivation here.

Indicator-by-indicator examination of the effects on drinking patterns of

the RTD tax

Consumption patterns since measure

introduced shows total alcohol sales only marginally reduced, if at all

DSCIA

provided the Committee with early market reaction to the tax change as reported

by the AC Nielson Liquor Scan Track Service for the two week period ending 11 May 2008. This showed:

- A 39 per cent decrease in the sales of dark spirit-based RTDs

(such as whisky, run and bourbon preferred by male drinkers aged over 25);

- A 37 per cent decrease in the sales of light spirit-based RTDs

(such as vodka, gin and white run preferred by females); and

-

A 20 per cent increase in the sales of full strength spirits.[23]

Mr Mott, ALSA told the Committee that while it is not yet

possible to determine the long term effect of the measure:

...from the data that is available to date it may well be that the

net total consumption of alcohol has increased...[24]

Mr Mott further commented:

As I said, in some areas there seems to have been a lift in

sales of beer, but it is hard to measure, and also increased sales of sweeter

styles of wine. The beer would be, typically, four to five per cent alcohol and

the wines, typically, six to 12 per cent ABV. So, while it is too early to tell

if the net amount of alcohol consumed—or, more importantly, any alcohol

misuse—has risen or declined, it does not appear that there has been any

significant public health benefit from this measure; it is simply a further

distortion in the nature of the beverages sold in the market place.[25]

This evidence is in contrast to the conclusions of other

witnesses, eg the Public Heath Association which postulated that early

indications are that the tax “is effective in reducing introduction to alcohol

amongst young women...”[26]

In fact there appears to be no clear evidence on consumption levels at this

early stage, with the market no doubt discovering and adjusting to the excise

increase. DSICA commented:

I think it is a novel concept that people would stop drinking...[27]

Liberal senators believe that careful analysis will be

required into whether alcohol sales actually reduce, and in particular whether

such reductions are attributable to the decisions of young drinkers or of adult

ones who currently make up the majority of consumers of RTDs.

Substitution and the popularity of

spirits among younger drinkers

The industry asserts that in recent years there has been a

change in product preference but not a change in consumption:

It can be seen the increase in the popularity of RTDs has been

primarily in substitution for bottled full-strength spirits and full-strength

beer, and is not due to an overall increase in consumption.[28]

This was echoed in the comments of Dr Anthony Shakeshaft,

National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre:

So when you just look at the drinking habits of underage people

– and the date we have got is for 12- to 17-year-olds – they tend to be very

price inelastic around alcohol, so they have got a clear preference for

spirits.[29]

Mr Warwick Ryan, Director, Government Relations, KPMG told

the committee:

Certainly the market evidence here in Australia that we have

included in our submission has shown a very significant substitution of

full-strength spirits, and there is anecdotal evidence that there has been

substitution of beer and wine products as well. We are not aware of any international

evidence that shows that there would be a reduction in total alcohol

consumption as a result of a tax increase on one category of product.[30]

In support Mr Michael McShane, Managing Director, Brown-Forman Australia,

stated:

Yes, there has been a migration. Our experience so far is that

there has been a definite reduction in the amount of sales of RTD products

since the imposition of the tax, but equally there has been a significant shift

into full-strength spirits since that date. We also have anecdotal evidence to

suggest that there is switching going on into other categories, and I think the

opening comments in the Four Corners program on Monday night would have

shown that. Our experience is that there is definite shifting going on.[31]

IDA pointed out that while RTD consumption may decrease as a

result of the excise increase:

There is clear evidence through retail sales data since the

increase of the excise that there will be almost a direct substitution to beer,

cider (same strength), wine (three times stronger) and spirits (seven to 10

times stronger).[32]

IDA concluded that:

There is already sound evidence that the new RTD tax has simply

caused a shift in consumption from RTDs to the same or potentially larger

quantities of alcohol in the form of spirits, wine, cider and beer. [33]

Mr McKay from IDA described the early evidence to the

Committee:

The early evidence is indicating that the overall consumption of

alcohol will not be affected by this tax, as RTD consumers merely substitute

RTDs for other forms of mostly higher strength and/or cheaper alcohol.[34]

Mr Mott from ALSA noted that:

Although the early reports fully indicate a drop in sales of

RTDs, we are, as I have said, somewhat concerned at the lift in sales of

full-strength bottled spirits and other forms of alcohol beverages. Our members

have also noticed that, along with the increased sales of bottled spirits,

sales of soft drink mixers have also risen, suggesting a practice that may not

result in the stated benefits of the measure. It seems that the highly mobile

18 to 24 population are now buying full-strength spirits and mixing on the run.

People in that age group do not necessarily carry measuring jiggers with them

to mix. It seems highly unlikely that they will be accurately measuring the proportion

of alcohol in the mixed drink, resulting in disturbing variable and potentially

risky strengths of alcohol in their drinks. If they are mixing on the run, it

is almost impossible for them to accurately calculate the amount of alcohol

that is going into their drinks and the drinks of whoever they are sharing it

with. At least with prepackaged products it was a set amount of alcohol and it

was clearly labelled with the number of standard drinks.[35]

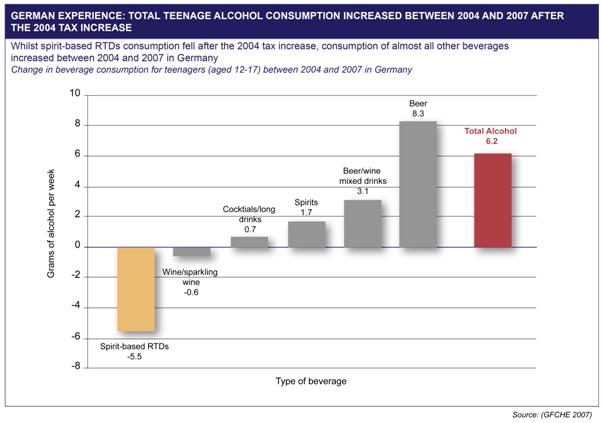

The experience of tax increases

in other countries here is illuminating. DSICA cites the case of a tax on RTDs

introduced in Germany in August 2004 which had the following impact over 3

years on total teenage alcohol consumption (see Figure 2).

Figure

2: German experience: Total teenage alcohol consumption increased between 2004

and 2007 after the 2004 tax increase

Source:

Submission No. 27 (Distilled Spirits

Industry Council of Australia), p.49.

If there is a preference among young drinkers for spirits or

spirit-based drinks, as both “sides” of this debate seem to concede, one would

expect a considerable problem with younger drinkers shifting from RTDs to spirits

to avoid the tax. Those problems may include an impaired capacity to count

standard drinks and a greater incidence of drink-spiking. These factors need to

be included on the debit side of the ledger when the tax’s implications are

tallied.

Capacity to count standard drinks

and the avoidance of drink-spiking

At the hearing DSICA told the committee about the unintended

consequences of the excise increase: Mr Gordon Broderick, Executive Director of

DSICA stated:

The government’s 70 per cent tax increase on a limited range of

alcohol products has created some potentially dangerous unintended

consequences, and these effects are already evident in the community. The

consequences are real and current and include inexperienced consumers being

driven to purchasing and mixing their own, stronger spirits and younger

drinkers opting for cheaper wine pops and cask wine, which contain twice the

alcohol and are taxed at half the rate. Young girls are facing the real risk of

being victims of drink spiking; highly respected medical experts are already

warning that teenagers are at risk of being drugged as they opt for buying open

drinks over the bar or at parties rather than safeguarding against drink

spiking by consuming drinks already premixed in a can or a bottle. There is

increased abuse by young men of full-strength beer, with the potential for

greater street and domestic violence. The tax hike trial has failed not only

because it does not achieve its objective but also, more dangerously, because

it has created a series of problems that continue as long as the trial

continues.[36]

IDA noted that:

Most RTD products on the market are actually at the lower end of

the scale at about the same strength as beer and provide a safer alternative

than straight or home-mixed spirits.[37]

Mr McKay outlined the benefits of RTDs:

Our benefits really are the benefits you associate with RTD

products—convenience, a premeasured serving of alcohol, clear labelling, and a

safe and secure pack.[38]

Substitution to illicit substances

Some witnesses expressed concern that one form of

substitution that could be expected is to illicit drugs, which in some cases

may become cheaper than RTDs. DSICA cited a 1997 study whose findings suggest:

...high

school students (the majority of whom initiated their alcohol and drug use

earlier) treat alcohol and marijuana as substitutes...[39]

Lack of evidence on which excise decision based

The Australian Hotels Association believed there was a lack of

evidence for the increase on the excise stating:

The Commonwealth Government has consistently highlighted

binge-drinkers as being young females, yet all the evidence suggests the real

consumers of pre-mixed alcohol products are 25+ single males. [40]

The AHA further asserted that 'there has been no evidence

presented by the Commonwealth that links price structure of the pre-mixed

alcohol market with binge-drinking' and 'there has been no evidence presented

by the Commonwealth that links the increasing popularity of the pre-mixed

sector with problem drinking patterns in young drinkers'.[41]

IDA also concluded that the basis for the 'singling-out of

RTD products is not backed up by research'. They argued:

There is limited published Australian research or data on the

role of specific alcoholic products on risky drinking behaviours and none of

it, that IDA is aware of, specifically nominates RTDs as the root cause of

binge drinking.[42]

IDA recommended that there needs to be better understanding of

the role played by not only RTDs but other alcoholic products in drinking

behaviours across both sexes and all age groups.[43]

IDA also pointed out that this measure will have a

considerable effect on their industry as RTD drinkers switch to other forms of

high strength and/or cheaper alcohol.

The Federal Government's excise increase on RTDs has the

potential to significantly impact the company; putting 480 jobs at risk,

including more than 250 jobs in Australia.[44]

Liberal senators believe that given the potentially negative

consequences, such as the potential loss of revenue and jobs for the industry,

such consequences should be carefully weighed and the evidence should be

conclusive.

Issue of aligning alcohol taxes with a volumetric approach

The Alcohol Education and Rehabilitation (AER) Foundation

argued that all alcohol should be taxed under one, consistent volumetric regime

which would save administrative costs and not favour any particular alcoholic

beverages.[45]

The AER provided the Committee with a diagram (available in

chapter four of the majority report) indicating a hypothetical tax rate to show

what a single rate of taxation would look like that produces revenue neutrality

but taxes by alcoholic content, not by drink type. Mr Daryl Smeaton, Chief Executive

Officer, AER, told the Committee that:

From a purist’s point of view, the foundation has said that it

does tax the alcohol in RTDs at the same rate as the alcohol and spirits. But,

as our hypothetical tax rate does show, when you apply a tax to the

alcohol—whether it is in beer, wine or spirits—at the same rate, you clearly

cannot tax them at the spirits rate. That would treble the amount of revenue

that the government would get and it would not make much change at all to

unsafe consumption, other than the fact that most people would not be able to

afford to buy alcohol any longer. One of the effects of applying an

across-the-board tax rate is that certain products would reduce in price, and

spirits are one of those products. But, as I pointed out earlier, the spirits

share the alcoholic market is only two per cent by volume; the beer market is

still by far the biggest part of the market, and I expect it would continue to

be so.[46]

Regarding alcohol taxation, Mr Smeaton further stated:

...But the fact is that the alcohol taxation system is broken. It

does not achieve anything other than a revenue stream for government. I have no

doubts that governments need to maintain revenue, but if we looked at the

alcohol taxation system from a public health perspective, as well as from an

economic perspective, then I think we could come up with a much better system

that would serve Australia equally well in both areas.[47]

Several

witnesses welcomed the excise increase as a step towards a volumetric approach

to alcohol taxation. It is however clear from the AER submission that

this is not true; AER suggests that a revenue neutral volumetric level of

taxation on RTDs would equate to a tax per standard drink of 47cents. In fact

the recent increase has raised the tax to $1.25.

Ironically

the tax level was closer to a revenue neutral volumetric approach before

the increase than it is now.

Other witnesses, notably those representing beer and wine

interests, highlighted the dramatic price changes across categories that would

stem from a shift to a pure, revenue neutral volumetric tax model. Australasian

Associated Brewers Inc provided modelling, verified by Access Economics, which

indicated the significant price increases beer and wine products would face,

compared with significant price reductions for spirit based categories under a

revenue neutral volumetric tax regime (see table 4).

Table 4 – Price

effects of volumetric taxation in dollar terms

|

BEVERAGE

|

CURRENT PRICE

|

VOLUMETRIC PRICE

|

+ / –

|

|

Spirits

(700ml)

|

$32.40

|

$20.40

|

–

$12.00

|

|

RTD> 7% (carton)

|

$72.03

|

$45.85

|

– $26.18

|

|

RTD< 7% (carton)

|

$72.03

|

$53.33

|

– $18.70

|

|

Wine (cask)

|

$15.14

|

$31.23

|

+ $16.09

|

|

Wine (bottle)

|

$11.81

|

$13.22

|

+ $1.41

|

|

Light Beer (schooner)

|

$2.92

|

$3.61

|

+ $0.69

|

|

Light Beer (carton)

|

$32.10

|

$35.90

|

+ $3.80

|

|

Mid Beer (schooner)

|

$3.34

|

$3.91

|

+ $0.57

|

|

Mid Beer (carton)

|

$30.15

|

$32.40

|

+ $2.25

|

|

Full Beer (schooner)

|

$3.85

|

$4.34

|

+ $0.49

|

|

Full Beer (carton)

|

$37.85

|

$39.02

|

+ $1.17

|

|

Premium Beer (schooner)

|

$5.01

|

$5.43

|

+ $0.42

|

|

Premium

Beer (carton)

|

$40.43

|

$41.53

|

+

$1.10

|

Source:

Submission No.34 (AAB), p.4.

Several witnesses indicated that a strictly volumetric

approach could be tempered by variations. DSICA posed the options of an

excise-free threshold, the phasing in of volumetric rates and, in particular, a

"series of tiered rates ...whereby lower content beverages are taxed at

lower volumetric rates."[48]

It is important to note however that even if a moderately tiered arrangement

were adopted in the future, the excise on RTDs recently imposed would be way

out of kilter with such a scheme.

Conversely, the excise imposed on RTDs would be consistent

with a volumetric approach if the Government were to lift overall taxation

levels on alcoholic products substantially. This may have health benefits but

is not part of any general strategy which has yet been spelt out to the

community. The Committee is conscious that the Henry Review might encompass

such options; Liberal senators trust there will be appropriate consultation

with affected industries and the broader community before such a move is

adopted as the Government’s policy.

Support of many health groups

conditional on Government's "follow up" with an across-the-board

volumetric approach – little evidence that this will occur

Although many health groups supported the excise measure,

their support was conditional that this was just one measure to address harmful

alcohol consumption of young people and should be part of a comprehensive suite

of measures such as volumetric taxation.

The AMA noted the focus on RTDs alone may provide 'perverse

incentives for young people to shift their preferences to potentially more

harmful behaviours or alcohol substitutes' and advocated:

Uniform application of a volumetric alcohol tax to ensure that

there are no incentives for people to shift their drinking preferences to

cheaper, but higher alcohol volume products.[49]

The AMA stressed that raising the excise tax on RTDs should not

be applied in isolation and a multi-faceted strategy should address controlling

supply and reducing demand.[50]

They further noted the 'RTD tax increase alone will not solve the problem and

it is simplistic to suggest otherwise'.[51]

Similarly, the Australian General Practice Network qualified

its position on the new tax:

To summarise our position, we do support the current approach,

although we would not support it if that was the end of it. We do support it if

it is part of a broader approach to risky behaviour with alcohol amongst young

people. We do support a volumetric approach and we would like to see, in that

approach, incentives to produce lower alcohol products. We also believe very

strongly that there need to be targeted strategies to increase the capacity of

the primary health-care sector in dealing with risky alcohol consumption.[52]

Professor Michael Moore of PHAA also struck a note of

caution:

We just described it as a first step and we continue to describe

it as a first step because, as we stated in our submission on the alcohol toll

bill, we believe that a comprehensive approach is critical. That comprehensive

approach should include pricing measures.[53]

Liberal senators saw scant indication of the broader prevention

and education measures which might be expected under such a multi-faceted

strategy. Officers of the Department of Health told the Committee that the task

force working on a preventive health strategy is not due to report for more

than a year.[54]

Lack of any present device to measure the ongoing success of this excise

increase

Ms Virginia Hart, Assistant Secretary, Drug Strategy Branch,

Department of Health and Ageing told the Committee during estimates hearings

that they were in the process of designing an evaluation for all components of

the binge drinking strategy and also the increase in excise.[55]

At the hearing the department reinforced that:

...the RTD excise is only one lever being used to tackle

adolescent binge drinking. We are in the process of now trying to devise an

evaluation to look at how all the initiatives that we have set out will

contribute to tackling binge drinking.[56]

No timeline for completion of an evaluation instrument was

provided. Liberal senators were disturbed to hear that no device was available

or was being contemplated by the Government to test its new tax’s

effectiveness. They further suggest that the blending of other anti-binge

drinking measures into the purview of an eventual evaluation instrument will

make isolating the success or failure of this measure even harder.

Evidence of sweetness as a "hook" for RTDs

Regarding the attractiveness of RTDs to young palates due to

their sweetness, Mr Broderick from DSICA told the committee:

I think the high sugar content is an assertion. I have not seen

any scientific data saying that the ready-to-drinks have higher sugar content

than any fruit juices or soft drinks. The most common component of the

ready-to-drinks is probably cola. I do not think they are artificially highly

sweetened for any devious purpose. This strawberry wine would be very sweet.

People could well migrate to that.[57]

DSICA later added:

A 375 ml can of Coca Cola has 39.8 grams of sugar compared with

33.4 grams in a 375 ml can of Jim Beam and cola, which is representative of

DSICA member pre-mixed products. That is, the 375 ml can of Jim Beam and cola

has 16% less sugar than the same size can of Coca Cola soft drink.[58]

Mr McShane supported this and stated:

Over 90 per cent of the ready-to-drink products in Australia are

actually served with cola, and those are cola bases which could carry similar

sorts of sugar levels and caffeine levels, for example, as a standard cola that

you would buy in a supermarket.[59]

Mr McShane also added that sweetness is not necessarily an

inducement to drink more:

There is a term that we use in the industry: ‘sessionable’. You

cannot drink too much sweet product because it just becomes sickly on the

palate, and so, in fact, sweetness is not necessarily an inducer. It can

actually be a negative. So excessive sweetness is not necessarily a good thing.[60]

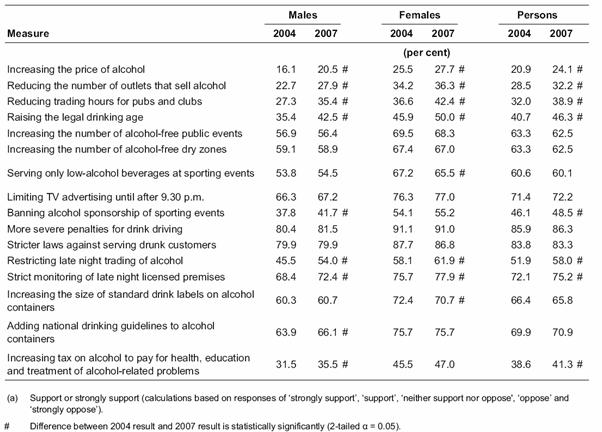

Support by Australians for other strategies

Liberal senators note that Australians

polled by AIHW rate a number of measures to combat alcohol abuse well ahead of

increases in tax levels (see Table 5)

Table 5 –

Support(a) for alcohol measures: proportion of

the population aged 14 years or older, by sex, Australia, 2004, 2007

Source: AIHW 2007 National Drug Strategy Household Survey:

first results, April 2008.

Respondents listed "More severe penalties for drink

driving", "Stricter laws against serving drunk customers" and

"Strict monitoring of late night licensed premises" as their highest

priorities. These measures attracted support at about twice the rate of

"Increasing tax on alcohol".

Liberal senators are unaware of any moves by the Government to

address the alcohol-related measures supported by most Australians, even to the

extent of encouraging their colleagues in the state and territory governments

to contemplate action.

Conclusion

Given the evidence for the excise increase is not clear and

that there are potential negative consequences such as substitution, punishing

responsible drinkers, and potential industry job losses, the question of

whether the tax should proceed is problematic based on the evidence.

Liberal senators are not opposed in principle to strong new

weapons to attack the culture of alcohol abuse. Indeed they acknowledge that

such measures must be seriously contemplated by all levels of government, for

example liquor trading hours and the number of retail outlets need to be on the

table for examination. But any measure adopted must pass a basic test of

commonsense and adequately-researched efficacy. We remain concerned that this

has not occurred here.

We support close examination of a volumetric method of

alcohol taxation, or variations thereof, such as a scaled approach that gives

low alcohol products a market advantage. We are not however convinced that the

Government’s RTD tax is part of such a strategy.

Accordingly, Liberal senators recommend that the RTD

excise increase be reversed until the Henry Review

of Australia’s tax system has reported and a response devised.

| Senator Gary Humphries, Deputy Chair |

Senator Sue Boyce |

| |

|

| Senator the Hon Richard Colbeck |

Senator Simon Birmingham |

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page