Chapter 4

Issues raised during the inquiry

4.1

The majority of evidence presented to the Committee expressed support

for the excise increase on spirit-based RTD beverages. In addition, the issue

most raised with the Committee was whether the measure goes far enough. It was

suggested that other measures would also be of benefit in addressing the issue of

risky and high risk drinking by young people as part of a comprehensive approach.

There were also a number of questions and concerns about unintended consequences

presented which will be detailed below.

Towards a comprehensive approach

4.2

While supporting the measure as a first step, the majority of submissions

argued that raising alcohol taxes needed to be part of a comprehensive approach

to address the harmful and hazardous use of alcohol which included controlling

supply as well as reducing demand. The only people who did not support the

measure and argued it was a retrograde step were from the industry.

4.3

The National Drug and Research Institute (NDRI), while recognising the

potential of the increase in the excise on RTD alcoholic beverages, drew the Committee's

attention to the body of evidence that showed a package of measures are

required to address the issue most effectively.[1]

This was supported by the Australian Medical Association (AMA) which believed

that a stronger and multi-faceted approach is required to change harmful

drinking patterns which included the use of price signals to discourage alcohol

consumption.[2]

4.4

The Curtin Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer Control noted that

reviews of international literature indicated that a combination of policy,

economic, educational and environmental measures was required to obtain maximum

results.[3]

4.5

The Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP), which supported the

measure as the most cost-effective, cited evidence which found that:

Modelling health-related reforms to taxation of alcoholic

beverages has demonstrated that alcohol tax reform on its own is not effective

and must be carried out in conjunction with other strategies.[4]

4.6

The Alcohol Education and Rehabilitation (AER) Foundation believed that

a holistic solution was required to address excessive alcohol consumption and

that it should not be limited to young people.[5]

The need to address other age groups was supported by the Victorian Alcohol

and Drug Association which also highlighted the need to acknowledge the

cultural context of alcohol use in strategy development:

Strategies to address excessive and harmful alcohol consumption

by young people need to acknowledge the role alcohol plays in young people's

lives as they transition from youth to adulthood. Equally important, strategies

need to address broader cultural attitudes to alcohol and set about effecting

change in attitudes and behaviours across age groups.[6]

4.7

Dr Raymond Seidler, a specialist in addiction medicine, suggested that a

comprehensive national strategy should also address the underlying issues of

alcohol dependence in Australia generally and for young people in particular.[7]

This approach was supported by the AMA which noted the harmful consumption of

alcohol has become part of the culture and this must be addressed. To do so

they advocated a strategy that addressed social norms in the same way as the

efforts to reduce smoking have produced new social norms.[8]

4.8

Submissions noted that all the players involved in the alcohol

issue should be part of the strategy and they encouraged industry to play a key

role.[9]

Submissions from industry pointed out that risky and high risk drinking is an

industry wide issue which requires an industry wide solution.[10]

The Committee notes that evidence from industry representatives

indicated a willingness to be part of a process to produce a comprehensive strategy.[11]

4.9

A number of submissions suggested a range of possible additional

measures to address harmful alcohol consumption and this is dealt with in

further detail below.

Work underway

4.10

The Government has already acknowledged that a range of measures are

required to address harmful alcohol consumption in the community, that this measure

is a first step, and has noted there is significant work already underway in

this area including:

- The National Alcohol Strategy 2006–2009 which was developed

through collaboration between Australian governments, non-government and industry

partners and the broader community. It outlines priority areas for coordinated

action to develop drinking cultures that support a reduction in alcohol-related

harm in Australia;[12]

- The National Binge Drinking Strategy was announced by the Prime

Minister on 10 March 2008. In particular, it announced three measures to reduce

alcohol misuse and 'binge drinking' among young Australians:

- community level initiatives to confront the culture of 'binge

drinking', particularly in sporting organisations;

- earlier intervention to assist young people and ensure they

assume personal responsibility for their 'binge drinking';

- advertising that confronts young people with the costs and

consequences of 'binge drinking';[13]

- On 26 March 2008, COAG asked the Ministerial Council on Drug

Strategy to report to COAG in December 2008 on options to reduce binge drinking

such as: closing hours, responsible service of alcohol, reckless secondary

supply and the alcohol content in RTDs. To acknowledge the urgency required to

address alcohol abuse, this work has now been brought forward to July 2008.[14]

COAG also asked the Australia New Zealand Food Regulation Ministerial Council

to request Food Standards Australia New Zealand to consider mandatory health

warnings on packaged alcohol.[15]

4.11

A comprehensive list of forums considering alcohol issues is available

in the Senate Community Affairs Report on the Alcohol Toll Reduction Bill 2008.

Further measures

4.12

Witnesses reinforced the need to look at additional options to reduce

binge drinking. Submissions suggested a number of areas including:

- packaging/labelling;[16]

- strategically designed education programs on the health and

social harms to reduce consumption;[17]

- ensure uniform laws, involving heavy penalties, on the provision

of alcohol to teenagers;[18]

- law enforcement initiatives;[19]

- legislation to place limitations on the density of liquor outlets;[20]

- control the time limit for purchase of alcohol as well as the

rate/volume purchased;[21]

- modifications to the rules governing advertising, marketing,

promotion, media and sponsorship;[22]

- consideration of the promotional links between alcohol and sport;[23]

- the role of parents as role models and supervisors;[24]

- reducing the allowable alcohol content in RTDs to no more than

three per cent;[25]

- reducing the availability of alcohol;[26]

- raising or gradually raising the drinking age to 21 as by this

age the brain is better protected from brain damage as a result of alcohol

consumption;[27]

and

-

review of alcohol taxation (addressed in more detail below).[28]

4.13

The RACP informed the Committee that an evaluation of international

literature found the following list of nine 'best practices' to deal with

alcohol related problems:

Alcohol control policies

- alcohol taxes;

- minimum legal purchase age;

-

government monopoly of retail sales;

- restriction on hours or days of sale;

- outlet density restrictions.

Drink-driving countermeasures

- sobriety check points;

- lowered blood alcohol content limits;

- administrative license suspension;

- graduated licensing for novice drivers.[29]

4.14

Submissions also mentioned a comprehensive strategy taking into

consideration associated issues such as the role of primary care and the

pressure placed on treatment services for alcohol related issues and workforce

development.[30]

4.15

The question of the responsibility of parents was discussed during the

hearings primarily due to the AIHW finding that among underage drinkers of

RTDs, alcohol is usually sourced from a friend or acquaintance, or from a

parent.[31]

Professor Robin Room, Alcohol and other Drugs Council of Australia, acknowledged

that parents face a difficult task regarding the most appropriate ways to

introduce and control the consumption of alcohol. In response to questions from

the Committee he advised:

I think it is appropriate for a parent to be reminding their

children of the law that applies at least outside their own home. Within their

own home, again, there are going to be differences.[32]

4.16

Professor Michael Moore, Chief Executive Officer, Public Health

Association of Australia, told the Committee that he thought governments could

support parenting by giving them ideas to consider and to that end any

marketing campaign should also reach parents as well as young people. He also

emphasised the significant influence of parents as role models.[33]

4.17

The NDRI noted that Australians are currently more receptive to measures

to address alcohol-related harm. They cited the 2007 National Drug Strategy

Household Survey findings that there has been a significant increase in public

support for changes in alcohol related policy, including support for increasing

the price of alcohol and increasing the tax on alcohol to pay for health,

education and treatment of alcohol related problems.[34]

The issue of hypothecated tax is addressed later in this chapter.

Conclusion

4.18

The Committee notes the consistent argument from witnesses that the

measure to raise the price of RTDs, although a positive step, would be more

effective if it was part of a comprehensive strategy to address the harms

associated with alcohol consumption for not only young and underage drinkers

but all at-risk drinkers. This comprehensive strategy would involve all the stakeholders

and the Committee particularly commends the willingness of industry to be

involved.

4.19

The Committee also notes the government has already acknowledged that a

range of measures will be required to address harmful alcohol consumption. The Committee

commends the work currently underway in this area including the announcement of

the National Binge Drinking Strategy and the targeted work being undertaken for

COAG regarding options to reduce binge drinking with an interim report now due

in July 2008. The Committee is aware that some of the additional measures

raised in evidence to this inquiry will be included through the COAG work but

strongly supports the whole range being considered as part of the review.

4.20

The Committee also supports the work being undertaken for COAG to raise

a proposal to consider mandatory health advisory labels on packaged alcohol. The

Committee is pleased to note the receptiveness of the public to measures to

address alcohol related harm found in the National Drug Strategy Household

Survey and urges the Government to take into consideration the increased public

support for changes in alcohol related policy.

Recommendation 1

4.21

The Committee supports the introduction of the excise increase on spirit

based RTDs, and does so in acknowledgement that it is one in the context of a

range of measures undertaken or to be considered to address harmful alcohol

consumption by young people.

Recommendation 2

4.22

The Committee notes that some of the additional measures suggested to

the Committee will be included in the work being undertaken for COAG but

strongly supports the whole range being considered as part of the review.

Interpreting the data

4.23

Some submissions questioned the conclusions drawn from data from the

AIHW and the NDSH Survey. They suggested the evidential link between increasing

the price of RTDs and a reduction in binge drinking among young women is

tenuous at best. Organisations such as Diageo, Australian Hotels Association, the

Winemakers' Federation of Australia and Wine Grape Growers' Australia pointed

out that overall alcohol consumption fell between 2004 and 2007 and that

between 1991 and 2007 for those aged 14 years or older, alcohol consumption

patterns remained largely unchanged. They contend that there is no evidence to

support the current crisis over the levels of risky drinking of either gender.[35]

4.24

Industry also noted that 75 per cent of RTDs are dark spirits mainly

favoured by men aged 24 years or older[36]

and of the remaining market for light RTDs, they asserted approximately 29 per

cent of the volume was consumed by males.[37]

Conclusion

4.25

The Committee notes some confusion caused by interpretations of data by

various stakeholders and the tendency to highlight minor variations between

individual studies. Despite this debate on data, which will no doubt continue,

there is no mistaking the unanimous conclusion of the health and medical

professionals that there are unacceptably high rates of risky and high risk

alcohol consumption by young people, rising rates of alcohol-related harm and

hospitalisations and increasing social costs.

4.26

The Committee does not accept that there is no evidence for undertaking

the measure to increase the excise on spirit-based RTDs. The Committee acknowledges

the data showing overall alcohol consumption remaining largely unchanged. It

also notes that within this, the drinking patterns and preferences vary considerably

across age and sex as described in the previous chapter. The Committee agrees

there are widespread indicators that young people commonly engage in risky

drinking behaviour at unacceptable levels and that action must be taken to

protect what appears to be a significant proportion of young people from the

harms resulting from drinking to excess.

4.27

The Committee recognises that RTDs are not exclusively consumed by

adolescents and teenagers and they are not the sole alcohol product preferred

by this age group. The Committee notes that the RTD data from industry

understandably does not cover underage drinking and therefore turns to the data

presented in detail in chapter three for this age group. In particular the Committee

notes RTDs are of concern as they are one of the most popular alcoholic

beverages, the most common first-used alcoholic beverage among younger age

groups and are the preferred drink for young people who drink at risky levels.

4.28

In reaching this conclusion the Committee notes data such as the 2006 ASSAD

survey which showed an increasing preference for RTDs among 12 to 17 year old females.

AIHW data also showed a significant increase in the consumption of RTDs. There

was also a clear preference among females in the 16 to 17 age group for

premixed spirits in a can and premixed spirits in a bottle which was the

highest preference for that age group. The NDSHS also showed a strong

preference among females between 12 to 17 for pre-mixed spirits and bottled

spirits. The Committee notes the conclusion from the AMA that this data indicated

'a policy focus on RTDs is justified as part of a total alcohol strategy'.[38]

4.29

The Committee also notes the research on behaviour cited in submissions

such as the NDRI which reported that when adolescents consume alcohol, most do

so at risky levels with 85 per cent of alcohol consumption for females aged 14

to 17 years and 18 to 24 years at risky or high risk levels for acute harm.[39]

More recent data confirmed these findings in a number of studies and surveys

all showing high rates of harmful drinking.[40]

The Committee notes the results from the recent NDSHS indicating that 9.1 per

cent of 14 to 19 year olds (and a greater proportion of girls than boys) drink

at risky or high risk levels at least once a week. The AMA noted that while

this survey did not indicate an increase in risky and high risk drinking in

this age range since 2004, the findings were still a matter for significant

concern due to the increased vulnerability of this age group to the effects of

alcohol and increased risk of harm.[41]

4.30

In addition to drinking preference changes and associated health effects,

the Committee also notes the high levels of harm due to alcohol consumption

outlined in chapter three. The Committee agrees that the current levels of

risky and high risk alcohol consumption by young and particularly underage

drinkers are unacceptably high. The evidence strongly indicates that action

needs to be taken to prevent both the health and social consequences of risky

drinking behaviour in young people.

4.31

The Committee notes that industry has acknowledged the level of public

concern with the voluntary action to reduce the amount of alcohol to two

standard drinks in their RTD products. Despite this voluntary action evidence

from organisations including the Australian Psychological Society contended

that self regulation did not appear to be working.[42]

The Committee notes that the industry acknowledged that reducing the incidence

of intoxication of young people should be a priority area and have shown a

willingness to provide input, work in partnership and be part of the solution.[43]

Potential for substitution

4.32

Submissions noted that the increase in growth of RTDs had come at the

expense of bottled full strength spirits and full strength beer[44]

and that if pre-mixed spirits became too expensive those who wished to binge

drink would move down the alcohol cost curve and simply substitute RTDs with

other, cheaper alcohol. Submissions cautioned that while certain customers may

respond to price increases by altering their total consumption, others would

respond by varying their choice of type or quality.

4.33

Industry sources, including Diageo, noted that one alternative would be

for the customer to purchase a bottle of full strength spirits and use mixers

to make their own RTD which is likely to result in non-standard drinks which

make it difficult to keep track of alcohol consumed.[45]

4.34

AHA agreed that instead of a reduction in alcohol consumption there

would be a shift to other products such as bottles of spirits or beer. They

further stated that an increase in alcohol was a blunt instrument which merely

disadvantaged that product in the market as consumers move to other options.[46]

The Australian Wine Research Institute also cautioned that reductions in sales could

be mitigated by substitution between beverage types.[47]

4.35

To address this issue various groups have called on the Government to

impose a higher uniform tax across all alcohol types to discourage 'drink

hopping'.[48]

Drug Awareness (NSW) also believed there was potential for young people to

switch to other spirits and mix their own drinks and that this highlighted the

need for much higher taxes on all alcohol.[49]

The issue of alcohol taxation is addressed in more detail later in this chapter.

4.36

The NDRI noted the importance of the taxation strategy because where

discrepancies exist, those who seek intoxication at the lowest price may engage

in substitution. However, they noted that it was important to place the issue

of substitution in a wider context as the degree to which this undermined the

overall effect of restrictions on the availability of alcohol was likely to be

limited.[50]

A recent review of alcohol restrictions noted:

A minority of drinkers, retailers and producers will always seek

to find a way around restrictions, but it is nonetheless possible to anticipate

how and where substitution practices may occur and to implement strategies to

limit their impact.[51]

4.37

Professor Robin Room, ADCA, told the Committee that some consumers will

switch to another alcoholic beverage which is cheaper but it won't be a

complete switch. He summarised:

You certainly will be able to find people who will say, 'Now I

drink something else.' But that does not mean that the tax has not had an

effect. It is very likely to have some kind of effect, partly on ground of

taste and partly on grounds of whatever choices people make in their lives.[52]

4.38

Professor Michael Moore, PHAA, acknowledged the potential for

substitution but told the Committee:

The fundamental question we are asking is: how can we reduce the

level of harm associated with heavy drinking of alcohol? And, fundamentally, it

comes back to a cost-benefit analysis that says that, even though some people

will move to hard spirits, we believe that this first step on the taxation of

these particular drinks is likely to reduce harm overall and that a more

comprehensive approach will be much more effective in reducing the harmful use

of alcohol. We see this as a good first step, but only as a first step.[53]

4.39

Regarding the potential for substitution Professor Steve Allsop, NDRI, advised

monitoring and pointed out to the Committee that mixing your own drinks was

already a cheaper option available to young people prior to the increase in

taxation.

Even before the increase in taxation, it was cheaper to buy a

bottle of spirits and to buy your own mixer. So it was not a widespread

practice then; there is no evidence that it will become a widespread practice

subsequently.[54]

4.40

Dr Tanya Chikritzhs, NDRI, emphasised that substitution effects are to

some degree inevitable but:

The overall finding for all of the studies that we have been

able to review is that the substitution effects are minimal compared to the

overall benefits that are brought about by the restrictions.[55]

4.41

Dr Alexander Wodak, RACP, told the Committee that a small proportion of

the population consumed a disproportionate amount of the alcohol consumed in the

community and concluded:

When we have relatively small changes in availability or price

relative to income, we have large changes in consumption, with a lot of that

consumption accounted for by people drinking immoderately and therefore

exposing themselves and other to great harm.[56]

4.42

Ms Virginia Hart, Assistant Secretary, Drug Strategy Branch, Department

of Health and Ageing told the Committee during estimates hearings that they were

in the process of designing an evaluation for all components of the binge drinking

strategy and also the increase in excise.[57]

At the hearing the department reinforced that:

...the RTD excise is only one lever being used to tackle

adolescent binge drinking. We are in the process of now trying to devise an

evaluation to look at how all the initiatives that we have set out will

contribute to tackling binge drinking.[58]

Recommendation 3

4.43

The Committee notes the potential for alcohol substitution to occur and supports

the government's commitment to evaluate the effectiveness of the measure

increasing the excise on spirit-based RTDs and all components of the binge

drinking strategy.

Conclusion

4.44

The Committee acknowledges the potential for substitution of RTDs with

other alcoholic beverages, particularly by those whose sole purpose is to become

intoxicated. The Committee notes the data released by DSCIA over a two week

period which may indicate a tendency for this to occur for some consumers but

concludes the timeframe is too short to draw meaningful conclusions. The Committee

also notes the evidence by organisations such as the NDRI that the degree to

which substitution undermines the overall effect of restrictions on the

availability of alcohol is likely to be limited. The Committee was also

cognisant of international data outlined in chapter three which appears to

support this. The Committee supports the government's plan to evaluate the

increase in excise and urges the government consider additional strategies as required.

Alcohol taxation issues

4.45

The majority of submissions drew attention to the anomalies that existed

in the alcohol taxation system, which do not help to achieve good health policy

outcomes and called for these inconsistencies to be addressed.

4.46

Below is a detailed description of the current tax system by DSICA:

All categories of alcohol are subject to the GST at the general

rate of 10 per cent. In addition to the GST, wine, beer and spirits are subject

to different Commonwealth alcohol taxation regimes. Beer, spirits and

ready-to-drink alcohol beverages below 10 per cent alcohol content are subject

to excise or customs duty. Australian produced beer, spirits and pre-mixed

products are subject to excise duty, collected by the Australian Taxation Office.

Imported beer, spirits and pre-mixed spirit products are subject to customs duty

collected by the Australian Customs Service. However, imported spirits and

pre-mixed spirits (but not beer) are also subject to an additional 5 per cent

ad valorem customs duty, or protective tariff. Excise duties and customs duties

(excluding the 5 per cent ad valorem tariff) are set on a volumetric basis, ie.

levied on the actual amount of alcohol in the product. Excise duty and the

volumetric component of the customs duty are set at the same level for each

alcohol category, and are automatically increased twice a year (1 February and

1 August) to take account of movement in the consumer price index in the

previous six months. All wine (including cask and bottled wine, other grape

wine products such as marsala and vermouth, mead and sake, and traditional

cider) is subject to the Wine Equalisation Tax (WET). WET applies at the rate

of 29 per cent of the last wholesale selling price (usually the last sale from

the wholesaler to the retailer). The taxation of wine differs to the tax

situation in relation to beer, spirits and ready-to-drink products in two

significant ways. Firstly the WET is levied on an ad valorem basis (ie. a tax

on value) rather than on the alcohol content of the product. Secondly, there is

no automatic six monthly indexation of the WET as there is for spirits and

beer.[59]

4.47

The majority of submissions called for a comprehensive review and reform

of alcohol taxation. The overwhelming view from public health advocates and some

elements of industry was that alcohol taxation should be largely based on

alcohol content and as much as possible this should be true within and between

beverage classes. Submissions argued that from a public health perspective,

there was no basis to discriminate between alcohol beverages.

4.48

The National Drug Research Institute (NDRI) noted that:

The most effective taxation strategy to prevent and reduce

alcohol related problems is one where all alcoholic beverages are taxed

according to their alcohol content.[60]

4.49

The Alcohol Education and Rehabilitation (AER) Foundation welcomed the Government's

move to tax RTDs at the same volumetric rate as bottled spirits as the first

step to a fairer alcohol taxation system. The CEO, Daryl Smeaton, urged that

further action needed to be taken to address taxation inconsistencies around

products such as cask wine, cheap fortified wines such as port and full

strength beer which continued to have advantageous tax rates and has urged the

government to undertake a full alcohol taxation review.[61]

AER proposed that all alcohol products should be taxed according to the amount

of alcohol contained in the package:

Imposing a consistent tax by volume regime across all beverage

types will help change the consumption patterns that lead to binge drinking in

both young and old.[62]

4.50

The Australian Drug Foundation also called for a volumetric based

taxation regime, arguing that the current system facilitated the sale of

high-alcohol products at cheap prices.[63]

The volumetric approach was also supported by the Public Health Association of

Australia[64]

and Independent Distillers Australia[65]among

others.

4.51

The NDRI suggested a tiered volumetric tax where the base tax was

determined according to alcohol content and an additional 'harm index' was

applied to beverages shown to be particularly problematic and/or associated with

high levels of harm.[66]

4.52

Higher taxes on strong beverages was supported by Professor Robin Room

who suggested the general principle of 'taxing according to the volume of pure

alcohol in the beverage and setting taxes high enough to mildly discourage

consumption'.[67]

He advocated modification of these general principles in the following ways:

- a higher tax for strong beverages of 20 per cent alcohol and

higher to reflect the much greater possibility of overdose from these

beverages;

- a lower tax for weak beverages below 3.5 per cent to encourage

switching to low-alcohol beverages;

- a higher tax to respond to problematic fashions and social trends

such as beverages favoured by young binge drinkers; and

- the imposition of a minimum price level on each type of beverage

which particularly affects underage and heavy drinkers.[68]

4.53

Ms Kate Carnell, AGPN, suggested an escalation approach which has

incentives for industry to produce low-alcohol products with under 3.5 per cent

alcohol.[69]

4.54

Those industry groups which modelling shows would be most advantaged

strongly supported a volumetric tax. Diageo also described the current tax

system as unnecessarily complex and called for volumetric tax as the most

effective, efficient and equitable way to tax alcohol as:

The effect on the body is the same whether the alcohol is

consumed from a beer, a wine or a spirit.[70]

4.55

DSICA contended that the current different types and rates of taxation did

not achieve positive social and health and outcomes and would add to the issue

as it provided stronger incentives to produce and consume alternative and

cheaper beverages.[71]

4.56

The AER told the Committee a comprehensive review of the alcohol

taxation system is required as:

It is broken. It is unfair. It is inconsistent. And it does not

tax alcohol as alcohol. It taxes beverages according to the way they are made;

and, of course, in the case of wine, according to the value put on that wine by

the manufacturers.[72]

4.57

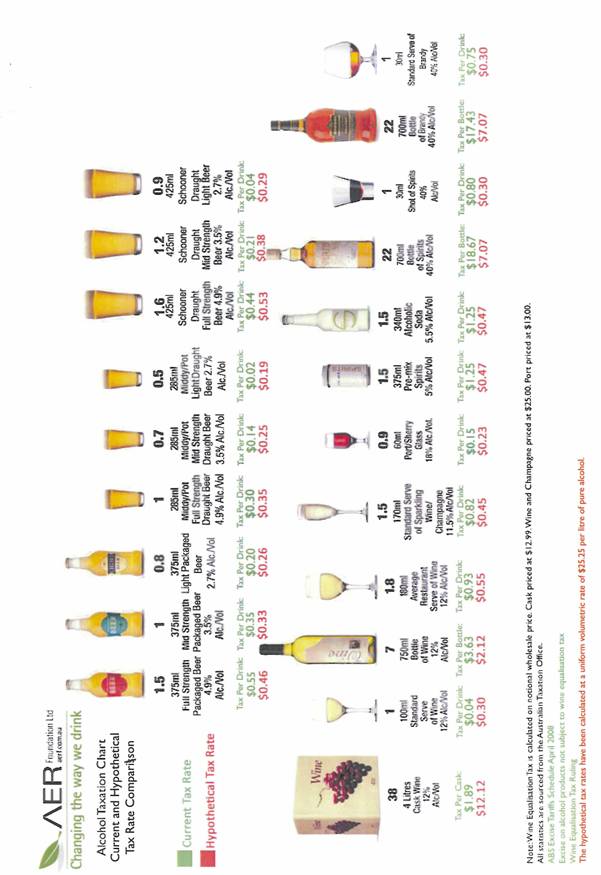

Modelling was provided by the AER[73]

(see diagram below) which shows volumetric taxation would mean significant

changes for the industry. It shows a hypothetical tax rate calculated at a

uniform volumetric rate of $25.25 per litre of pure alcohol.

4.58

Mr Daryl Smeaton, Chief Executive Officer AER, emphasised the modelling

was not a recommendation but an example of what a single rate of taxation would

look like that produced revenue neutrality and reduced consumption. He added:

I think there are a whole range of models that should be looked

at, but they must all have one fundamental element to them—that is, they must

tax the alcohol as alcohol and not as wine, beer or spirits. There is no

difference in the alcohol in beer or wine or spirits in terms of the potential

harm its excessive consumption can cause. That is the fundamental reason for a

comprehensive review of the taxation system. It should not be based on how the

product is made, who makes it or what its economic benefits or disbenefits are;

it should be reviewed from a public health perspective. This is an industry

that gets $30 billion a year in alcohol sales and that creates, on a very

conservative estimate, $15.3 billion worth of harm—and we think that is a very

conservative estimate.[74]

4.59

The Brewers Association for Australia and New Zealand provided the

Committee with independent modelling from Access Economics on volumetric

taxation which found that this system would result in the fall of prices of all

spirits and beer and wine prices would rise. On this basis the association

submitted that there were industry, agriculture and health policy reasons to reject

volumetric taxation as compared to the range of spirits and wine products, 'all

beer is low alcohol'.[75]

4.60

The rejection of volumetric taxation was supported by the Winemakers' Federation

of Australia and Wine Grape Growers' Australia which argued that taxation was a

blunt instrument which did not distinguish between responsible and harmful

drinking. They contended that wine was not attractive to younger drinkers and

therefore not the product of choice for most underage drinkers.[76]

This was observed in the data from the AIHW where it was shown that this change

in drinking pattern picked up when consumers reached their twenties.[77]

A number of submissions, however, called for measures to address harmful

alcohol consumption in all age groups.

4.61

The wine sector also noted that any measures to increase taxation in the

wine sector or change the way the product is taxed would have a negative effect

on employment and regional communities which were already dealing with the

challenges associated with the drought and water prices.[78]

4.62

When speaking to the Committee Mr Stephen Strachan, Chief Executive,

Winemakers' Federation of Australia, highlighted the following effects of a

volumetric tax for the wine industry:

A uniform volumetric tax at, say, the beer rate would lead to an

increase in the price of a $12.50 cask of wine to $28; an increase in price for

all bottled wine that currently sells below $25, which accounts for about 98

per cent of all the wine that we sell in Australia, including cask wine; a

reduction in wine demand, resulting in a drop of about 250,000 tonnes of grapes

required by the industry for the domestic market; and about 3,500 fewer

employees—in terms of the people who are employed by that part of the business.

It would also of course result in a drop in the price of spirits and would

result, at the beer rate, in a modest drop in government taxation revenue,

although it would be very modest. A revenue neutral volumetric type tax across

all alcohol would necessarily be slightly higher than the beer rate, and that

would obviously lead to even more pronounced impacts on the wine industry.[79]

4.63

While sensitive to the concerns of industry, in response to questioning

from the Committee on the effect of volumetric taxation on the wine industry, Professor

Richard Mattick, Director, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, told the

Committee:

I think you have to think about what the severity of the impact

might be. The example given here was that a 10 per cent increase might affect

consumption by less than 10 per cent. It is not stopping five per cent of

people drinking; it is reducing consumption overall by five per cent, and that

is the desired effect. A five per cent reduction in consumption would be, I

would suggest, something that the industry could bear. It has seen good growth

over time. One has to ask: does the industry have the unbridled right to grow

and complain when anybody calls attention to this issue and calls foul, or are

we thinking, ‘Hang on, the consumption in Australia is getting to be high’—and

it has been high for a long time—and thinking about some reasonable measures

which respect the industry’s right to continue to employ and to produce? Also,

the industry makes a lot of money by exporting overseas, and presumably some of

these tax measures will not be affecting it there. But I still think that the

government needs to have some control over consumption.[80]

4.64

Dr Anthony Shakeshaft, Senior Lecturer, National Drug and Alcohol

Research Centre, argued that a volumetric taxation system would provide the opportunity

for industry to better align with public health goals:

From a public health perspective, what we want to see is an

overall reduction in average consumption—how much people drink all the time—as

well as a reduction in how much people drink on one occasion. That is the idea

of the long-term harm as opposed to the short-term harm. We think once you take

out the price differential, then there is an opportunity to get the industry to

compete on things other than price that, as I said, would align better with

public health. For example, you could get them to promote things like lower

alcohol beverages. They could compete to increase in their market share on

issues that use those kinds of strategies rather than just on price.[81]

4.65

Ms Karen Price, Manager of Operations and Development, National Drug and

Alcohol Research Centre, emphasised that aligning public health goals with

industry goals would be the optimal outcome. She stated:

Part of the reason that it [data] is tricky and confusing is

that you have two different groups telling you different messages because they

have different goals. You should have them swinging behind the same goal, and I

think a taxation discussion about alcohol should be about that.[82]

4.66

On the issue of alcohol taxation, the Department of Health and Ageing

stated that in the context of harm minimisation:

there is support for a tax system that provides incentives for

the production, sale and consumption of lower alcohol content beverages and for

using taxation and price to maximise harm minimisation outcomes. The evidence

indicates this can have the impact of reducing overall alcohol consumption and

correspondingly reducing related problems for individuals and communities.[83]

4.67

While supporting a move towards a volumetric tax, Dr Alexander Wodak,

RACP, cautioned that the tax relief for low-alcoholic beverages should not be

removed.[84]

Hypothecated tax

4.68

A number of submissions strongly advocated spending more of the alcohol

profits on education programs and public health campaigns to encourage everyone

to drink safely. Submissions also suggested directing a proportion of the

revenue collected from taxes on alcohol towards funding the Government's

response to the health, social and economic harms resulting from alcohol

misuse. The RACP noted that this measure had been shown to reduce the level of

alcohol-related harm.[85]

This was also supported by organisations including the AMA[86],

the Royal Australasian College of Physicians[87],

the Australian Drug Foundation,[88]

the Australasian Therapeutic Communities Association,[89]

and the Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association[90]

among others.

4.69

Witnesses at the hearing also spoke strongly about the benefits of a

hypothecated tax. Professor Room, ADCA, told the Committee:

It makes sense to use part of these revenues [from alcoholic

beverages] for prevention and treatment programs aimed specifically at alcohol

problems. Such programs should be based on evidence about what is effective and

cost-effective. The rest of the revenues might well be used to support general

health and social welfare services. Alcohol consumption places great burdens on

these systems in terms of emergency department visits, hospital admissions,

family welfare and child protection assistance and so on. The revenues from

increased alcohol taxes would go some way toward paying for these externalities

which alcohol consumption imposes on Australian society.[91]

4.70

The Public Health Association believed that government recognition

should be given to the revenue from the excise increase to be used as part of a

complete package to address the problem and that the funds raised should go

towards 'a comprehensive approach to harmful and hazardous use of alcohol'.[92]

4.71

At the hearing the Ms Jennifer Bryant, First Assistant Secretary,

Population Health Division, Department of Health and Ageing told the Committee

that:

Minister Roxon has stated on the public record that the

government will be looking to direct a substantive proportion of the funds

raised through the excise measure to preventative health activities. Exactly

what those activities will be is still a matter for decision by government...[93]

Conclusion

4.72

The Committee notes the concerns about using tax to control alcohol

consumption as well as the call to tax alcohol content equally, regardless of

product. The Committee also recognises that the support for volumetric taxation

is not unanimous and notes the differing modelling submitted to the Committee. The

Committee fully supports the inclusion of the examination of alcohol taxation in

the current review of the taxation system being chaired by Mr Ken Henry.[94]

4.73

The Committee notes that although wine is a product of choice for an

older age group, this would not deter those whose prime motivation is drinking

to become intoxicated. The Committee also notes the wine industry concerns

regarding potential changes to the alcohol taxation system and urges the

government to take these concerns into consideration during the examination of

alcohol taxation.

Recommendation 4

4.74

The Committee supports the call for a review of alcohol taxation and

notes that an examination of alcohol taxation will be included in the

comprehensive review of the tax system currently underway (the Henry Review).

Other issues

4.75

The Committee noted the submission from the Chrisco Group which raised

the effect of the excise increase on retailers which have pre-sold RTDs at a

fixed price established prior to the increase in the excise.[95]

Conclusion

4.76

The Committee is of the view that the measure undertaken by the Government

to increase the excise on spirit-based RTDs, and this inquiry, have contributed

to the important debate of the role of alcohol in society and the negative

effects of harmful consumption, particularly for young people. The Committee is

aware of and shares the high level of public concern regarding the unacceptable

rates of risky and high risk alcohol consumption of young and underage

drinkers. Young people are particularly vulnerable to alcohol in terms of its effect

on their development, their lack of experience of drinking and the increased

likelihood to engage in risky behaviour which may result in their harm or the

harm of others. The Committee recognises that the vast majority of submissions from

researchers, health and medical professionals supported raising the excise as a

significant step to address this public health issue.

4.77

While some evidence focussed on the drinking patterns of older males and

RTDs the primary aim of the Committee was the effect of alcohol on the short

and long term health of young people. The Committee acknowledges data which

shows the relatively stable consumption patterns for people aged 14 years or older;

however, it also recognises that within this data, drinking patterns and

preferences vary considerably across age and sex. The evidence shows a

widespread problem with the illegal consumption of alcohol by underage

drinkers. Evidence also shows that a significant proportion of underage

drinkers are risking harm to themselves and others by engaging in risky

drinking behaviour.

4.78

There has been a growth in new alcohol products over recent years and

the Committee notes the significant growth in the consumption of RTDs and that they

are being consumed at risky and high risk levels by young drinkers. While this

increase may have been at the expense of other alcoholic beverages there is no

denying the attractiveness of RTDs for young and underage drinkers. They are

often their first drinks, their most preferred, they mask the taste of alcohol

which makes them palatable to very young drinkers, have colourful packaging and

a relatively high alcohol content for those whose objective is rapid

intoxication. Young females in particular display a preference for sweet

tasting and colourful RTDS. The Committee agrees that measures need to consider

the drinking preference of at-risk adolescents and teenagers where evidence

indicates that RTDs are particularly appealing.

4.79

The data from surveys and studies shows young females have stronger

preferences for pre-mixed drinks in a can or bottle when compared to young

males. Across a number of surveys RTDs have become more popular, showing a

substantial increase in consumption, particularly among young girls. However,

the Committee notes the figures are concerning for both sexes. The

attractiveness of RTDs is also evident in the sales figures with an increase of

more than 450 per cent between 1997 and 2006.

4.80

The Committee notes some confusion caused by interpretations of data by

various stakeholders and the tendency to highlight minor variations between

individual studies. Despite this debate, which will no doubt continue, there is

no mistaking the unanimous conclusion of the health and medical professionals

that there are unacceptably high rates of risky and high risk alcohol

consumption by young people and rising rates of alcohol-related harm and

hospitalisations.

4.81

The Committee agrees there are widespread indicators that young people

commonly engage in risky drinking behaviour at unacceptable levels and that

action must be taken to protect what appears to be a significant proportion of

young people from the harms resulting from drinking to excess.

4.82

The level of public concern has been recognised by the industry itself

as evidenced by the voluntary action taken to reduce the amount of alcohol to

two standard drinks in their RTD products in response to the level of concern.

Despite this voluntary action the Committee notes evidence that this appears to

be having minimal effect, however, the Committee commends the willingness of

industry to be part of the solution.

4.83

Evidence clearly demonstrates the high levels of risky and high risk

drinking behaviour and the consequences of this can be found in ongoing

negative health effects, including motor accidents and hospitalisations. The

data on treatment episodes, preventable health problems, deaths and hospitalisations

all clearly show unacceptable increases for young people. These health findings

alone justify the measure undertaken by the government. In addition to the

negative health effects, evidence also shows an increase in the levels of

sexual assaults, physical violence and criminal activity which affects not only

the young people involved but also the broader community.

4.84

The Committee agrees that the current levels of risky and high risk

alcohol consumption by young and particularly underage drinkers are

unacceptably high. The evidence strongly indicates that action needs to be

taken to prevent both the health and social consequences of risky drinking

behaviour in young people.

4.85

The effect of alcohol taxes on risky and high risk alcohol consumption

by young and underage drinkers is a complex question and the Committee

acknowledges the potential for drink substitution to occur. DSICA put forward

data collected over a two week period to support this argument. However, the Committee

concludes that the timeframe is too short to draw meaningful conclusions. The Committee

also notes the evidence by NDRI and others which argued that the degree to

which substitution undermined the overall effect of restrictions on the

availability of alcohol was likely to be limited. Therefore, the Committee

urges the government to monitor and evaluate this aspect and consider additional

strategies as required.

4.86

The Committee notes the consistent argument from witnesses that while

supportive of the measure to raise the price of spirit-based RTDs it would be

more effective as part of a comprehensive approach to address the harms

associated with alcohol consumption by young and underage drinkers. The Committee

notes the government has already acknowledged that a range of measures are

required to address harmful alcohol consumption in the community through the

implementation of the National Binge Drinking Strategy and looks forward to the

outcomes of the targeted work being undertaken for COAG regarding further options

to reduce 'binge drinking' due in July 2008. The Committee is aware that some

of the additional measures raised will be included through the COAG work but

strongly supports the whole range be considered as part of the review. In

formulating any additional measures, the Committee urges the government take

advantage of the increased public support for changes in alcohol related policy

to address alcohol related harm found by the National Drug Strategy Household

Survey.

4.87

The inquiry has also highlighted the inconsistencies in the current

alcohol taxation system. The Committee acknowledges the concerns about using

tax to control alcohol consumption as well as the call to tax alcohol content

equally, regardless of product. The Committee recognises the call for

volumetric taxation was not universal and there were variations between a flat

or tiered level of taxation by its advocates. The concerns expressed by the

wine industry and the suggestions for exemptions and modelling provided were

noted by the Committee. The Committee supports the examination of alcohol

taxation being included in the Henry review of the taxation system and urges

government to consider the concerns raised and the evidence for and against

volumetric taxation submitted to the inquiry.

4.88

The public health issues of problematic drinking among young people are

clear and each action that reduces such drinking makes a contribution in public

health terms. For all the reasons listed above the Committee agrees with the

vast majority of evidence presented to the Committee, particularly by health

and medical professionals, which was supportive of the measure to increase the

price of spirit-based RTDs as one of a range of measures to address harmful

alcohol consumption in the community and particularly among young people. The Committee

notes this is a complex issue and one that will require further effort and

input from governments, professional bodies, researchers, treatment and

prevention services, media, industry and the community to develop the next

steps.

Senator Claire

Moore

Chair

June 2008

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page