Culturally competent services

A culturally safe health system is as important as a

clinically safe health system. As evidence shows, when people experience

culturally unsafe health care encounters they will not use health services or

they will discontinue treatment, even when this maybe life threatening.[1]

4.1

The focus of this inquiry, the accessibility and quality of mental

health services in rural and remote Australia, is of particular importance to Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples. As noted in Chapter 3, Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples are much more likely to live in these areas than

non-Indigenous Australians.

4.2

The health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is

far poorer compared to non-Indigenous people and addressing this health

disparity is the goal of many close-the-gap programs. Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples are have disproportionately low outcomes on almost

every scale of social, health and wellbeing.[2] Of relevance to the health focus of this inquiry, the rate of admissions to specialised

psychiatric care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is double

that of non-Indigenous Australians.[3]

4.3

The previous chapter outlined key barriers to the accessibility and

quality of mental health services in remote communities of Australia. These

included 'tyranny of distance' issues, workforce shortfalls and a lack of

appropriate support services, among others.

4.4

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, there is the added

need for those services to be culturally competent in order to provide an

appropriate, and adequate, service that does not re-traumatise people through

the denial of their cultural needs. An overwhelming body of evidence presented

to this inquiry shows that the lack of culturally competent and safe mental

health services results in significantly lower rates of Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples accessing the mental health services they need.[4]

4.5

This chapter will outline the frameworks of culturally competent mental

health service delivery in rural and remote locations, discusses the improved

health outcomes when services are culturally competent, and explores the

barriers to culturally competent service delivery. Although services which

target alcohol and other drugs (AOD) services are often co-located with mental

health services, this chapter will focus on clinical mental health services and

social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB) programs, as well as suicide prevention

strategies.

Service contexts

4.6

An overwhelming majority of submitters and witnesses cited the causes of

mental health problems for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as

being significantly different to non-Indigenous Australians, in that the causes

are primarily poor social determinants of health[5] which leave families and whole communities in crisis, combined with the trauma

caused by historical factors. A wide body of research has found that these

historical factors include intergenerational trauma, racism, social exclusion, and

loss of land and culture.[6]

4.7

The Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW (AHMRC)

submitted that the compounding impact of removal from families, racism and loss

of culture through past assimilation policies left communities with high levels

of disadvantage and ill health.[7]

4.8

A General Practitioner from Kununurra discussed the range of causative

factors leading to mental health problems that she encounters as being

intergenerational trauma, sexual abuse and 'a whole breakdown of cultural

values, cultural connections, that we see; it's all absolutely contributing to

that.'[8]

4.9

The National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO)

submitted that:

[I]t is not possible to consider best practice mental health

models of service for Indigenous people without considering culture, including

an understanding of the multi-faceted impact that intergenerational trauma has

on Indigenous people and its inextricable link to mental health, and social and

emotional wellbeing.[9]

4.10

Prior to discussing the cultural competence of mental health service

delivery, it is important to outline the context in which those services are

being delivered. The following sections outline key service delivery factors

within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Dispossession and colonisation

4.11

Evidence to this inquiry from a range of organisations noted that the

colonisation of Australia involved the disruption and severing of many of the

connections that are at the heart of social and emotional wellbeing and good mental

health for Aboriginal people.

4.12

Witnesses noted that these impacts are still felt in Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander communities today. The Aboriginal Medical Services

Alliance Northern Territory (AMSANT) noted that the current delivery of mental

health, SEWB and AOD services, generally without local input and governance,

replicates some of the harmful aspects of colonisation and has significant

implications for accessibility of services.[10]

4.13

The Medical Director of Wurli-Wurlinjang Health Service made a similar

observation:

The wellbeing of the community is affected by dispossession,

by poverty, by all these other things, by lack of respect from the Australian

government ...which has disempowered and continues to do that on a fairly

spectacular basis.[11]

4.14

Miss Nawoola Newry, a local advocate, pointed out that the direct outcomes

of colonisation occurred in Kununurra in living memory, which meant the trauma

was still fresh within that community.[12]

Collective and intergenerational

trauma

4.15

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation (Healing

Foundation) submitted that intergenerational trauma, where the impacts of

trauma continue down through multiple generations, is complex in its impacts as

it is both collective and cumulative. It is collectively experienced across

communities, it is cumulative over a life-span and can be passed from one

generation to the next.[13]

4.16

The Healing Foundation further submitted that the impacts of collective

trauma can be devastating, as it can cause whole community breakdown and a loss

of connection to community. This emphasises the need to provide collective

healing responses, as individual treatment interventions alone cannot address

this collective factor. The failure thus far to tailor healing efforts at a

community level means families continue to live in vulnerability without the

strength of a community to assist them to heal.[14]

4.17

The Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association told the committee

that the collective trauma of the stolen generation continues to impact

decisions to access mental health services, as 'there is a very strong fear now

still alive for Aboriginal people that welfare will be involved in your family

and you might lose your children. That does have an effect.'[15]

4.18

The committee also heard of the build-up of collective grief, where

communities were dealing with multiple instances of crisis and loss. A

psychologist for the Ord Valley Aboriginal Health Service described this as:

...people being in a constant state of grief and loss. They

have relatives dying consistently. We are talking about people attending a

funeral every week. They are almost in a cycle of grief and loss continuously.[16]

4.19

AMSANT submitted that the combination of these historical and present

day experiences of trauma result in the disconnections in aspects of life that keep

people well and strong and underlie the complex mental health, SEWB and AOD issues

that impact Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.[17]

Social determinants of health

4.20

Many submitters and witness argued that the provision of mental health

services will not alone address the mental health gap between Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians, as many of the

causes of poor mental health and wellbeing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples are the social determinants of health, such as housing access,

adequate food and educational and job opportunities.[18]

4.21

The Manager of the Social Emotional Wellbeing Unit for Yura Yungi

Medical Service told the committee that housing was a significant factor in

stress-related mental health issues:

There's an extensive waiting list on the housing commission,

up to four to eight years. What we find is that this builds frustration. I

honestly think it has sometimes led to suicide, because people are frustrated,

they can't get out of it and there are arguments and things like that within

families.[19]

4.22

Townsville Aboriginal and Islanders Health Services told the committee

that many instances of clients with depression or anxiety are found to have

external stressor causes:

When the doctor talks to them, or even the health worker, in

their yarning they usually find out that it's more of a social thing. It might

be overcrowded at home or dad's not working—he's unemployed—or Billy might be

running off all the time and not going to school.[20]

4.23

The Social and Emotional Wellbeing support worker from the Kununurra

Waringarri Aboriginal Corporation discussed the levels of crisis that

individuals deal with on a regular basis, which leads to feelings of being

overwhelmed, such as dealing with 'housing, Centrelink, the courts, juvenile

justice and all that kind of stuff. A lot of them find it quite daunting and

hard to deal with.'[21]

4.24

The AHMRC argued that mainstream mental health services are not capable

of addressing the social determinants of wellbeing.[22] Mrs Gillian Yearsley, the Executive Director of Clinical Governance and

Performance with the Northern Queensland Primary Health Network (PHN) affirmed

this view and told the committee that:

Current mental health service models are based upon models of

care which are culturally inappropriate and which do not target the underlying

systemic issues within those communities. This impacts upon the health and

wellbeing of all community members, such as housing, employment, education,

access to healthy food and the areas which link to the social determinants of

health.[23]

4.25

The AHMRC pointed to the need for 'equitable funding and resource

allocation towards the determinants of health and wellbeing such as safe and

affordable housing, access to affordable nutritious food, and vocational and

educational opportunities.'[24]

Impacts of trauma on child

development

4.26

The committee heard a range of evidence that showed the social and

historical determinants of health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples often has a more sharply felt negative impact on children.

4.27

The Healing Foundation submitted that the impact of trauma on children

can effect emotional regulation, attachment, aggressive behaviour and

developmental competencies.[25] This can be compounded by other risk factors experienced by Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander children, such as family disruption, family violence,

economic disadvantage, poor living standards, disengagement from school and

overcrowded housing.[26]

4.28

The Healing Foundation further submitted that medical research has also

shown that trauma interferes with childhood neurobiological development, impacts

responses to stress and increases a child's later engagement in correctional,

social and mental health services.[27]

4.29

The Youth Program Manager for the Shire of Halls Creek outlined that

there is higher than average presentation of youth with neurodevelopmental

disorders in that region which is generally undiagnosed until after they have

engaged youth justice services and these children 'are more likely than their

peers to have other mental disorders, such as anxiety, depression and

antisocial behaviour.'[28] The youth worker went on to detail other findings from diagnostic tools used on

this youth cohort:

Young people in the Olabud Doogethu program consistently

present with low baseline scores when tested against the Rosenberg self-esteem

scale, the Oxford happiness questionnaire, the social identification scale,

which relates to belongingness, and the Kessler psychological distress scale.

This indicates that clients have very little to no resilience skills.[29]

4.30

The Senior Medical Officer for the Nganampa Health Council told the

committee that the experiences of poverty, malnutrition, chronic stress and

exposure to violence damage the vulnerable minds and brains for children and

that this could cause physical changes:

The stresses are an ongoing thing. The high cortisol levels

not only change how your body works and ages more quickly from a cardiovascular

point of view but also the way the brain develops.[30]

4.31

A psychologist for the Ord Valley Aboriginal Health Service bluntly told

the committee that 'we've got kids who probably have the same circulating

stress hormones as people living in a combat zone—and that's what they're going

back home to.'[31] He further informed the committee that many of these children, some as young as

10 years old, self-medicate with cannabis to deal with their stress.[32]

4.32

The Mental Health Coordinator of the Ngaanyatjarra Health Service, a

mental health nurse, told the committee of child behaviour cases he sees, with

a range of possible causes such as 'alcohol, drugs, genes, genetics and in

utero stuff' and further told the committee it was things he had 'never seen

before within a city setting, the behaviours. A lot of it could be learnt

behaviours as well, plus the beginning of mental health behaviours.'[33]

4.33

One of the traumas experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

children in higher rates than non-Indigenous children is sexual assault. The

committee was told this can be caused in part by one of the social determinants

of health, overcrowded housing, which leads to children to being more

vulnerable to sexual assault because the 'protective factors of family being

able to provide safety are compromised.'[34]

4.34

A psychologist working for the Ord Valley Aboriginal Health Service told

the committee of the high rates of sexual abuse encountered among their client

population, which can be children as young as five to eight years of age:

Also, regarding seeing clients who are survivors of child

sexual abuse, I've never seen so many as in the Kimberley. I might have three

sessions a day sometimes that are survivors of childhood sexual abuse. So I

know we definitely need the services and skilled clinicians to help people

recover from that devastating history.[35]

4.35

The psychologist further stated that generally the presentation he sees

is an older female adolescent who is dealing with past trauma, who goes on to

being a long-term therapy client.[36]

4.36

The Sexual Assault Counsellor for Anglicare WA told the committee of the

impacts that child sexual assault can have on development:

Child sexual abuse can have a very significant impact on a

person's mental health both as a child and later on when they become an adult.

Child sexual abuse is often a factor in people experiencing mental illness. It

is identified as a factor in suicide and often results in personality

disorders.[37]

4.37

The Sexual Assault Counsellor for Anglicare WA further discussed the lack

of cultural competency in services to address issues of disclosure, including

training for local Aboriginal Health Workers:

There is a strong taboo against, and shame for, victims

speaking about sexual abuse, and this is especially the case for Aboriginal

people. There is a need for culturally appropriate education and resources to

be rolled out by people who are adequately trained. It is my opinion that we

need staff from both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal backgrounds engaged in this

work. Aboriginal workers may require training and mentoring to overcome the

taboo associated with talking about sexual abuse.[38]

4.38

AMSANT told the committee that the only child and adolescent mental

health services in the Northern Territory are in Darwin and Alice Springs and

said that children are only receiving psychiatric care at crisis point from

mainstream services that are not culturally safe for them.[39] Jesuit Social Services pointed out that this is compounded in the Northern

Territory, where clinical psychologists used to be provided in schools but that

service is no longer funded.[40]

Drug and alcohol issues

4.39

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities often have high rates

of drug and alcohol use, which compounds and increases the complexity of mental

health service delivery. The Ord Valley Aboriginal Health Service told the

committee that the use of cannabis was 'linked to psychosis' but that clients

reported they used cannabis as a coping strategy:

What we see also is people almost in a perpetual state of

grief and loss, continuously, with many of their relatives passing. So I

believe that, quite often, alcohol and drug use is self-medication for

underlying mental health disorders and psychological distress.[41]

4.40

A local advocate in Kununurra also raised the issue of self-medication,

often to deal with undiagnosed mental health issues:

Because so many [in the] community have these illnesses that

are undiagnosed they turn to alcohol and drugs to mask their issues. When

people are self-medicating on such a level in town it creates all these extra

issues out in community. There can be violent outbursts and everything, which

the family have to deal with, and then that can create further dysfunction in

the family, trying to deal with that as well.[42]

Kinship and family structures

4.41

The different notions of kinship held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples, alongside the increased cultural obligations to family, was

raised as an important service delivery context that was often overlooked by

non-Indigenous service providers. The Provisional Psychologist for the Derby

Aboriginal Health Service outlined that carer duties can impact on a client's ability

to attend appointments:

An Aboriginal person might book an appointment with me for 10

o'clock, but they don't rock up because Nan has said to them, 'I need to go to

Woolies at 10 o'clock.' I'm not prioritised. And why aren't I prioritised? I'm

not prioritised because they don't have to live the rest of their life with me;

they're going to live it with Nan, and Nan won't forget that they didn't take

her to Woolies at 10 o'clock when she needed to go...funders have difficulty

getting their heads around it.[43]

4.42

The committee was also told that Aboriginal families tended to be

larger, and for Aboriginal women with many children they found it difficult to

attend appointments while caring for their children.[44]

4.43

The committee was also told that the different family structures found

within Aboriginal communities can result in older Aboriginal women running

informal safe houses for children with limited resources, often funded by a

pension and under great stress:

These safe houses, which they run and organise and where

they've given their heart and their soul to the preservation of their children,

are really where the duty of care, in my view, shines...These are receiving

places within their community, built on a strong cultural base and on strong

relationships, either personal or otherwise....That's where the rubber hits the

road in this context. You asked the question: what are the cultural solutions?

There is one.[45]

Committee view

4.44

It is clear that the mental health service contexts for rural and remote

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are greatly different to

those for predominantly non-Indigenous communities. These differing contexts

include both the causes of mental illness, as well as barriers to the service

delivery itself.

4.45

The committee heard compelling evidence directly from rural and remote Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander people of the environments in which they live, work

and raise families and the impacts these environments have on social and

emotional wellbeing. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are

often operating in crisis mode, dealing with the continuing impacts of past

traumas such as colonial dispossession and the stolen generation, compounded by

ongoing traumas caused by high suicide rates and extremely poor social determinants

of health.

4.46

The committee also heard from a range of experts that those social

determinants of health have a far greater impact on individual mental health

outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples than that felt in

non-Indigenous communities.

4.47

It is clear to the committee that health and mental health services

which do not reflect these contexts are not only destined to fail, in the worst

cases these services traumatise and retraumatise the very people for whom they

are supposed to provide therapeutic treatment.

Culturally competent services

4.48

The Implementation Plan for the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Health Plan 2013–2023 outlines the importance of health services

being culturally competent.[46] The Implementation Plan states an intention that 'mainstream health services

are supported to provide clinically competent, culturally safe, accessible,

accountable and responsive services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples in a health system that is free of racism and inequality.'[47]

4.49

The Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and

Midwives (CATSINaM) submitted that for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples,

cultural wellbeing is inextricably linked to health outcomes, and pointed to

the National Aboriginal Health strategy definition of health:

Health is not just the physical wellbeing of the individual,

but the social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole community in

which each individual is able to achieve their full potential as a human being,

thereby bringing about the total wellbeing of their community.[48]

4.50

NACCHO also discussed the importance of culturally competent health services

and submitted that this competency directly impacts the health outcomes of Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples accessing those services:

Aboriginal people identify culture as key to mental wellbeing

and evidence highlights that programs and services which provide culturally

safe early intervention and prevention are the most effective in reducing the

likelihood of poor mental health and suicide.'[49]

4.51

However, NACCHO submitted that access to culturally secure mental health

services, particularly in rural and remote locations, is inconsistent and in

many cases is non-existent.[50]

What is cultural competence?

4.52

Before evaluating the cultural competence of mental health service

provision, it is useful to outline what cultural competence is and the impact

that cultural competence can have on the clinical outcomes of mental health

services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples.

4.53

The Centre for Cultural Competence provides a definition of cultural

competence in an operational context as 'the integration and transformation of

knowledge about individuals and groups of people into specific standards,

policies, practices, and attitudes used in appropriate cultural settings to

increase the quality of services, thereby producing better outcomes.'[51]

4.54

The Tangentyere Council provided a commonly used definition of cultural

safety as:

An environment that is spiritually, socially and emotionally

safe, as well as physically safe for people, where there is no assault,

challenge or denial of their identity, of who they are and what they need.[52]

4.55

The committee was told that culturally competent service provision is

fundamental to the mental health outcomes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

peoples. NACCHO submitted that the lack of culturally competent services is a

major barrier to Aboriginal people seeking the mental health care they need,

and that in 2012–13 seven per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

reported avoiding seeking health care because they had been treated unfairly by

medical staff.[53]

4.56

It was also acknowledged to the committee that cultural competence in

the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander service setting is not a one size

fits all solution. Each community will have different needs and a different

cultural context and traditions.[54]

Trauma informed and strengths based

care

4.57

The interrelated nature of trauma informed care and culturally competent

care was raised by submitters and witnesses across a number of contexts. It was

contended that without cultural competency, services for Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander communities could not be considered trauma informed, as they

often inflicted additional trauma on the very people using the service.

4.58

AMSANT submitted that the mainstream models of trauma informed care,

considered best practice in non-Indigenous settings, could not be considered

best practice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. AMSANT argued

it can in fact be harmful, because of the differences between non-Indigenous

and Aboriginal and Torre Strait Islander communities' belief systems and

historical experiences of colonisation.[55] AMSANT pointed to Culturally Responsive Trauma Informed Care as an approach of

best practice, which requires the service approach to be contextually tailored

and localised to the nuances of each location.[56]

4.59

The Healing Foundation contended that many mental health staff lack

education about the nature and impact of trauma on the mental health of Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The Healing Foundation submitted that

despite an increasing awareness of trauma informed care in mainstream health

services, there is a significant gap in the accessibility of genuinely

trauma-informed mental health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples.

4.60

The use of fly-in, fly-out (FIFO) services can be particularly

problematic if people are encouraged to talk about traumatic life events, and

then the service is unavailable for over a month leaving the community to

manage the distress of the individual, and in some case suicide attempts.[57]

4.61

The issue of FIFO services was raised by many other witnesses. The Kununurra

Waringarri Aboriginal Corporation told the committee that many people will not

engage with a FIFO service because the periodic nature of the service raises

trauma and then leaves it unresolved:

They're thinking: 'What's the point of going and speaking to someone

who's only to be [here] for a week? We're not going to see them again.'...If they're supporting a person

who's going to be permanently based here in town and they can put a face to a

name and know that that person is going to be here for good, I think it will

encourage them to come out and really speak about our story and talk about what

issues they might be facing.[58]

4.62

The Consultant Psychiatrist with the Kimberley Mental Health and Drug

Service described other health services which are standard for non-Indigenous

patients but can be traumatising to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples:

If there is a compelling health reason to keep someone in

hospital, then yes, of course we will do that. That's our duty of care and it's

our ethical, personal and professional obligation...However, a hospital is an

institution. It's a conventional western institution that's a traumatising

place...that will often make things worse.[59]

4.63

The Consultant Psychiatrist also described how the usual approach to

therapeutic questioning can also be traumatising for an Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander patient:

When I take a step back in the consulting room, rather than

me driving that and rather than me being a top-heavy, medical-down

practitioner, if I've asked a local person who can build a bridge between me

and the distressed person rather than me inadvertently retraumatising that

person by grilling them with interrogative questions, the person who's there

building the bridge, the Aboriginal person, makes it a safe interaction and

allows that person and their family to buy in to the strategies that will most

likely make a more meaningful and enduring difference.[60]

4.64

CATSINaM pointed to strengths-based approaches being linked to wellbeing

in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, as they assist in changing perspectives

of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and provide alternative ways to

approach social and emotional wellbeing.[61]

4.65

AMSANT pointed to a review conducted for the Closing the Gap

Clearinghouse, which found that programs that show positive results for Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples' social and emotional wellbeing are those

that are strengths-based, in that they 'encourage self-determination and

community governance, reconnection and community life, and restoration and

community resilience.'[62]

Cultural competency in

non-Indigenous services

4.66

As outlined above, a key concern raised regarding the cultural

competency of non-Indigenous service providers is the prevalence of the FIFO

model used to service remote communities.

4.67

The Regional Youth Program Manager for the Shire of Halls Creek

discussed how this model is incompatible for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander adolescent mental health, which favours a drop-in model. The FIFO

model means that '[r]apport building with clientele is difficult, and intensive

therapeutical intervention is almost impossible.'[63]

4.68

AMSANT said that FIFO services often do not have access to community

members who do not show up for an appointment–as discussed early in this

chapter this can often be for competing family duty issues. Services run by

local community members with relationships on the ground can have staff drive

around and find those people and then conduct a meeting in a safe environment.[64]

4.69

The Acting Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Jungarni-Jutiya Indigenous

Corporation gave a similar example, where a non-Indigenous service refused to

find a young man in need of mental health intervention, requiring him to visit

the service or attend hospital:

They waited four weeks until he went off his head. The system

doesn't work for people here because there's no real prevention on the ground.

They're all in these flash offices with the air conditioning and everything

else, but they're not on the ground out there where people can see them just

having a yarn with people. Mental health doesn't have to be that bad. If you

just go and have a yarn with somebody, you could stop those people from being

what they are in some cases.[65]

4.70

The Healing Foundation further submitted that government-funded services

need to reframe their thinking to recognise that service delivery failures are

due to a failure to build trust and safety with clients, rather than viewing Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander clients as being 'hard to reach.'[66]

4.71

Mr Nathan Storey, the chair of the Kununurra Region Economic Aboriginal

Corporation, told the committee that a lack of cultural awareness was also felt

in children's counselling services, where children did not engage because the

services were delivered 'in a little sterile room.' Mr Storey outlined how a

culturally competent children's service should engage with Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander children:

Take them out bush to hunt a kangaroo. Everyone will cook the

kangaroo and sit around eating damper and even marshmallows, if you want. We

will all sit, dance and sing. We will go to sleep and when we wake up we will

go fishing. We will come back. Eventually you'll get those kids opening up.[67]

4.72

The Youth Program Manager of the Shire of Halls Creek described how

external service providers continue to win service contracts, despite a low

success rate:

Services like this are not successful, and have not been able

to mobilise community buy-in; however, they continue to be funded. CAMHS—Child

and Adolescent Mental Health Services—have closed open cases on multiple

occasions due to little or no engagement with the client. So they've had a

referral, but when they come to Halls Creek every two to three weeks, they

can't find the client or the client does not want to engage, making rapport

building extremely difficult.[68]

4.73

The Healing Foundation contended that successful non-Indigenous service

models not only acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, but

value it as a fundamental cornerstone.[69] This issue was raised by many witnesses, who argue that a lack of service

co-design with local communities resulted in poor services which were not

utilised by the local community:

Little consultation occurs with our communities with regard

to identifying the level of need and service design. Decisions about operating

models are often focused on budget constraints rather than the number requiring

access to the service.[70]

4.74

The CEO of Aarnja Ltd, pointed out that too many service decisions

impacting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are made by

non-Indigenous people:

So when you look at, for example, some of our decision-making

in the Kimberley—no disrespect to the organisations or departments here—when we

sit in discussions on Aboriginal people, it's predominantly non-Aboriginal

managers who sit in that space. They're getting direction and some information

from their Aboriginal staff, but the Aboriginal staff aren't at that

decision-making table. That needs to be changed if we're going to get any traction

within the current system.[71]

4.75

Submitters and witnesses argued that not only are many mainstream

services in remote locations not culturally competent or responsive, they do

not appear to take action to address this issue. Many services do not provide

cultural awareness training.[72] Where it is provided, it is insufficient, ad-hoc and relies on online training

modules.[73]

4.76

The CEO of Aboriginal Interpreting WA told the committee that addressing

intergenerational and vicarious trauma will not happen 'if it's continually

attempted in high English without regard for traditional Aboriginal languages.'

The CEO informed the committee that English is not the first language for many

Aboriginal people in Western Australia and many are missing out on services

where no interpretation is offered.[74]

4.77

The Tangentyere Council pointed out that mental health services also

include phone counselling services, such as Lifeline and beyondblue, which 'are

frequently not appropriate for people where English is a second or third

language or where the people on the end of the phone do not understand the

cultural context of the people they are speaking to.'[75]

4.78

The Healing Foundation recommended that cultural competency should be

tested with agreed criteria and standards, and that local community input

should be required, with measurable outcomes relating to the client's

experience used as the primary indicator of success.[76]

4.79

The Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) told the committee that their

model of ensuring they are culturally competent is based on building

relationships with community controlled organisations:

We visit and work in community controlled organisations only

at the invitation of them. Over many years, those dynamics have developed such

that, for many nurse-led outposts, we provide the medical backup over the phone

and the emergency retrieval as required at the invitation of the community

controlled organisation. That will continue as we expand our mental health

service.[77]

4.80

The RFDS went on to say that the working model went beyond being invited

to a community, but included:

...the establishment of the service in response to local need...I

can flag that, as part of that very long established dialogue with community

controlled organisations, we'd only work where we're invited to do so with Aboriginal

communities and in the manner in which those communities want us to operate.[78]

4.81

Cyrenian House cited a similar approach, where that organisation

provides a monthly written report to the community councils outlining its recent

activities and seeking feedback from communities.[79]

Aboriginal community controlled services

4.82

The committee heard evidence from a range of organisations that the Aboriginal

Community Controlled Health Service (ACCHS) model of comprehensive primary

health care delivers better outcomes for Aboriginal people.[80]

Without exception, where Aboriginal people and communities

lead, define, design, control and deliver services and programs to their

communities, they achieve improved outcomes.[81]

4.83

The AHMRC submitted that for the majority of Aboriginal people, their

local ACCHS is their first point of contact with the health system and is their

preferred provider of primary care services. The AHMRC argued that Aboriginal

communities consider their ACCHS as integral to the wellbeing of the community,

and provides a gathering place where families can safely attend to their

physical and mental health needs.[82]

4.84

NACCHO also pointed to ACCHSs as best placed to deliver mental health

services to Aboriginal communities, as the community-based model of care involves

a sense of empowerment for Aboriginal people with mental illness.[83] Dr Denise Riordan, the Chief Psychiatrist of the Northern Territory, noted that

ACCHSs are also particularly good at delivering SEWB services.[84]

4.85

In some cases, to improve the cultural competency of external mental

health specific diagnostic tools, ACCHSs have rewritten the standard mental

health screening tools to adapt to local culture. This included ensuring that

the diagnostics were undertaken by health workers of the same gender as the

client, as required under local cultural tradition.[85]

4.86

In direct comparison to the clinical-setting services provided by many

non-Indigenous providers, the Derby Aboriginal Health Service outlined the

informal engagement methods they used to build rapport and trust with people

needing mental health support:

We have a community engagement model where a number of our

workers—our youth worker, our perinatal worker and our Aboriginal mental health

worker—actually spend a lot of time out in the community. So it's a more

relaxed approach...Ash, our male Aboriginal health worker, may go footy training

out of work hours and he may lean on the fence and have a yarn with someone.

It's in a very relaxed environment where the client or the patient feels

comfortable, but there's a consultation going on here. So we're reaching out.[86]

4.87

The Derby Aboriginal Health Service outlined that many Aboriginal people

will not attend state mental health services because of the history of institutions

for Aboriginal people.[87] The Danila Dilba Health Service made a similar observation, and pointed out

that the co-location of mental health services in ACCHSs meant that people who

are comfortable with their health service are more likely to access mental

health services located within the same facility.[88]

4.88

The Tangentyere Family Violence Prevention Program described the informal

environment they created to make clients feel safe:

We are surrounded by Aboriginal artwork, and the atmosphere

is welcoming and physically and emotionally safe. We understand that conducting

outreach to people's homes assists them to feel more in control. Many

conversations regarding challenging topics happen in the car.[89]

4.89

Dr Peter Fitzpatrick from the Wurli-Wurlinjang Health Service pointed

out to the committee that federal funding which used to resource the ACCHS

sector is now being diverted to fund PHNs, who then tender out services:

NGOs are all putting in tenders for chunks of money that

previously went to ACCHOs to provide services to Indigenous people, and that's

a concern for us. We've seen that here in Katherine. We've seen NGOs applying

for funding and winning the tender because they have access to great

tender-writers because they're multinational companies.[90]

4.90

Dr Fitzpatrick went on to state that ACCHSs have developed over time to

be highly effective health service delivery organisations:

There are 130-odd across Australia. They're a highly evolved

structure. We're general practice accredited. We're ISO accredited. We get

ticked off by ORIC and every other—we're, really, very organised organisations.

We've got state bodies and national bodies. And we're all paid for by the

Australian taxpayer, so use it. Use the structure that you've created instead

of bypassing it.[91]

Improved outcomes when services are

competent

4.91

The AHMRC pointed to the low numbers of Aboriginal people accessing

non-Indigenous mental health services, resulting in crisis presentation at

Accident and Emergency, resulting in admission for treatment and subsequent

community follow-up after discharge, at a cost of $19 728 per person. The AHMRC

submitted that evidence shows that better allocation of resources to the ACCHS

sector would result in a redaction of hospital admissions and associated costs,

because ACCHSs have made significant impact on the burden of illness in

Aboriginal communities and provide good value for money.[92]

4.92

NACCHO agreed with this view, noting that the ACCHSs sector was able to

deliver lower cost community-based mental health services and that these

services were closer to where people live, which assists in keeping people healthy

in the community and prevents hospital admissions.[93]

4.93

The AHMRC further submitted that although ACCHSs are making referrals to

funded non-government organisations (NGOs) and mainstream mental health

services, Aboriginal people are not presenting for those appointments, usually

as a result of inflexible and culturally unsafe practices in the organisations.[94] NACCHO agreed with this view and submitted that mainstream services are unable

to provide holistic and culturally competent care to Aboriginal people,

particularly those living in rural, remote and very remote locations.[95]

4.94

The Townsville Aboriginal and Islanders Health Services put forward a

similar view and told the committee:

We do have clients that still go out to the hospital, but

they don't ever return out there because of the way that they feel they're

treated. There's not a lot of Indigenous staff to support them when they're out

there, which, I suppose, comes back to resourcing and having enough staff to

help people.[96]

4.95

The Healing Foundation submitted that 'the most successful service

models to address trauma, healing and indeed mental health balance best

practice western methodologies with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

cultural and spiritual healing practices.'[97]

4.96

The Townsville Aboriginal and Islanders Health Services told the

committee of the successful services they delivered using this model, where

Queensland Health are co-located at their clinic. This enabled the services to

establish trust before making a mental health referral, as they 'sometimes go

through another channel instead of going straight to mental health.'[98]

4.97

The Executive Director of medical services at the Wurli-Wurlinjang

Health Service agreed with this view and told the committee that:

...the experts in Indigenous mental health are Indigenous

people. They're not psychiatrists, they're not mental health nurses, they're

not GPs, and we don't recognise that—we don't pay for it and we don't engage

with that group. Those other groups come in and value-add to it but they can't

actually resolve it.[99]

4.98

The CEO of Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services (KAMS) provided the

committee with an overview of all the positive outcomes that can be achieved

when services are culturally competent, which go far beyond improved service

delivery for individuals:

It will build local Aboriginal community capacity and

resilience through workers [being] trained and people feeling much more

comfortable in dealing with their own community. It will improve access and

coordination of care by having one-stop shops, so people don't have to try and

navigate this complex system. It'll help increase cultural awareness and

cultural safety of mainstream programs, because these workers can work with the

mainstream services to make sure that their programs and services are

appropriate. And it'll reduce costs of service delivery at the acute end if we

can keep people healthy and out of the expensive hospital system.[100]

4.99

Submitters and witnesses strongly argued that a culturally competent

workforce is the foundation to delivering culturally competent services. These

workforce challenges are discussed in detail in the following chapter.

Committee view

4.100

It is an accepted fact within various national health strategies and

implementation plans that health services must be culturally competent in order

to be effective. Cultural competency is not an optional extra. It is not a

gold-standard. Cultural competency is a basic benchmark that health services

must reach in order to meet the needs of the communities they serve, be they

urban, remote, non-Indigenous or a predominantly Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander client base.

4.101

The committee has heard overwhelming evidence that in rural and remote

locations, mental health services lack the cultural competency and safety required

to meet the most fundamental principle of medicine: first, do no harm.

4.102

The committee has also heard that the experts in cultural competency,

the local communities, have very little input into service design or scope of

practice. Clearly, until communities have greater say in what services are

funded and how those services will operate, mental health services for Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples in rural and remote locations will continue

to fail their patients.

Social and emotional wellbeing programs

4.103

The committee heard from many submitters and witnesses that SEWB

programs are fundamental to improving the overall mental health of Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander communities, both on an individual and a collective

level.

4.104

The Social Health Reference Group, responsible for developing the National

Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People's Mental

Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2004–2009, concluded that:

The concept of mental health comes more from an illness or

clinical perspective and its focus is more on the individual and their level of

functioning in their environment.

The social and emotional wellbeing concept is broader than

this and recognises the importance of connection to land, culture,

spirituality, ancestry, family and community, and how these affect the

individual.[101]

4.105

AMSANT stressed the importance of SEWB programs in Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander cultures (see Figure 4.1) and submitted that 'First Nations

Peoples of Australia maintained health and mental health through beliefs,

practices and ways of life that supported their social and emotional wellbeing

across generations and thousands of years'.[102]

Figure 4.1—Social and Emotional Wellbeing from an Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islanders' perspective

Source: AMSANT.[103]

4.106

The National Mental Health Commission's 2015 Review of Mental Health Programmes

and Services concluded that mainstream mental health services had largely

let down Aboriginal communities and recommended that integrated mental health

and SEWB teams should be established in all ACCHSs.[104] The AHMRC made a similar recommendation to this inquiry, that all ACCHSs are

funded to build and establish SEWB teams including Residential Rehabilitation

and Healing Services.[105]

4.107

AMSANT recommended that integrating SEWB, mental health and AOD programs

into primary health care services is the most cost-effective approach to the

delivery of metal health services in rural locations. AMSANT stressed that this

requires funding for multidisciplinary, culturally and trauma informed teams.[106]

4.108

AMSANT told the committee of a SEWB model developed by a working group

of the Northern Territory Aboriginal Health Forum, based on a combination of a

community based Aboriginal workforce and a mental health professional

workforce. AMSANT told the committee this model includes both a clinical and

community development prevention component and is particularly suited to remote

communities. It provides access to therapy in a culturally safe environment,

noting that the provision of cultural and social support is a crucial part of

mental health care.[107]

4.109

The Healing Foundation cited research which indicates that healing

programs are best delivered on country by people from the same cultural group

as participants.[108]

4.110

The Queensland Alliance for Mental Health discussed the importance of

early intervention SEWB programs in providing people with supports in the early

stages of mental illness, resulting in the diversion of those people from more

expensive hospitalisation or long term National Disability Insurance Scheme

funding. The organisation went on to say that in rural and remote areas, one of

the most effective interventions is community capacity building via informal

programs in local communities.[109]

4.111

The Chief Psychiatrist of the Northern Territory stressed to the

committee the need for a broad approach to mental health, and that while

clinical mental health services are important components in addressing mental

health related conditions, 'the promotion and maintenance of mental health in

the community is influenced by many complex social factors and really is the

responsibility of the whole of the government and the whole of the community.'[110]

Committee view

4.112

As outlined earlier in this chapter, the committee heard that the social

determinants of health in rural and remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander communities are not being adequately addressed and that these

communities are often operating in a continual cycle of crisis. The committee also

received evidence that the collective social and emotional health of the

community is vital to individual mental health outcomes for Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples.

4.113

These service contexts, however, are not being taken into account in

funding decisions and social and emotional wellbeing programs are not being

delivered to the extent needed in remote communities. It is clear to the

committee that increased focus on this form of early intervention would have a significantly

beneficial therapeutic impact to entire Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

communities.

Suicide prevention

4.114

Suicide is a major cause of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples' premature mortality and is a contributor to the overall Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples' health and life expectancy gap. In 2014 suicide

was the fifth leading cause of death among Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples, with the rate double that of non-Indigenous people.[111] In the 15–34 years age bracket, suicide is the leading cause of death[112] and those aged 15–24 are over five times more likely to commit suicide than

their non-Indigenous peers.[113] The Healing Foundation submitted that gender should also be considered as a

factor, as males represent a significant majority of completed Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander suicides.[114]

4.115

NACCHO noted that while the prevalence of mental disorders is similar

throughout Australia, the rates of suicide and self-harm are higher in rural

and remote areas, and these rates get higher as areas become more remote.[115] Again, this is more relevant for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples,

as the majority of suicides among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

occurred outside of capital cities.[116]

4.116

AMSANT discussed the findings of a review of suicide prevention

strategies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, which found:

High Indigenous suicide rates arise from a complex web of

interacting personal, social, political and historical circumstances. While

some of the causes and risk factors associated with Indigenous suicide cases

can be the same as those seen among non-Indigenous Australians, the prevalence

and interrelationships of these factors differ due to different historical,

political and social contexts.[117]

4.117

AMSANT further noted that this review found that one of the quality

indicators of suicide prevention services is culturally safe services and that

such services were optimally provided by ACCHSs.[118]

4.118

The Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Women's Council agreed

with this view of the non-mental health causes of suicide and told the

committee of their internal suicide register, which shows that half of all

suicides and attempted suicides have a clear link with domestic and family

violence.[119]

4.119

The Chief Executive Officer of the Northern Territory PHN noted that

culturally appropriate suicide prevention strategies need to be developed for

each community:

A prevention strategy that works on one community may have

very little impact on another. Culturally appropriate services need to be

developed, and community consultation and engagement is essential to this.

Those approaches need to be community led.[120]

4.120

NACCHO submitted that efforts to reduce suicide in Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander communities must do more than address social and economic

disadvantage and health gaps, and must also promote healing and building the

resilience of individuals, families and the whole community.[121] The Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Cultural Centre (KALACC) concurred with this

view and quoted an expert in indigenous suicide, Professor

Michael Chandler:

[I]f suicide prevention is our serious goal, then the

evidence in hand recommends investing new moneys, not in the hiring of still

more counsellors, but in organized efforts to preserve Indigenous languages, to

promote the resurgence of ritual and cultural practices, and to facilitate communities

in recouping some measure of community control over their own lives.[122]

4.121

KALACC cited the Western Australia (WA) Parliamentary report into

Aboriginal youth suicide, which found the need to focus more on a holistic

approach than a simple clinical approach[123] and recommended restoring culture and a sense of identity as a key protective

factor against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander suicide.[124] The CEO of KAMS also recommended that this report 'had a suite of

recommendations that we need to start to act upon.'[125]

4.122

The AHMRC submitted that evidence shows that programs and services which

provide culturally safe early intervention and prevention have proved to be the

most effective in addressing suicide.[126]

4.123

The National Suicide Prevention Trial, outlined in Chapter 2, involves a

number of trial sites, one of which is the Kimberley region of Western Australia

and targets Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This trial is

discussed below.

Kimberley suicide prevention trial

4.124

A decade-long audit quantified the suicide rate in the Kimberley among Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples as among the highest rates in the world.[127] The CEO of KAMS told the committee 'this means is that Aboriginal family

members in the Kimberley are losing loved ones at rates that are among the

highest in the world.'[128]

4.125

The trigger factors for suicide in the Kimberley region include alcohol

and other drug use, relationship difficulties, family conflict or a previous

suicide attempt, as well as other causal issues, including intergenerational

trauma, loss of culture and other social determinants, such as employment,

education, and housing.[129] KALACC argued that Aboriginal suicide in the Kimberley has very little to do

with clinical mental health.[130]

4.126

A Consultant Psychiatrist with the Kimberley Mental Health and Drug

Service concurred with this view and listed the causes of Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples suicide as the 'upstream factors' which also cause

substance use, poverty, children in custody and incarceration, stating that

'suicide is almost never due to a mental illness. So it's is not due to

something that we can diagnose and treat within a conventional Western model,

within a Western framework of how our hospitals and our clinics are set up.' He

went on to recommend that increased funding for clinical services was not the

answer:

People who are at risk of or complete suicide have drowned at

the end of the stream. If you give us more resources to catch more people with

nets before they drown, then of course we will catch more people before they

drown. However, that doesn't address the upstream factors.[131]

4.127

The committee was told that the National Suicide Prevention Trial was

not culturally competent to factors in the Kimberley region. The CEO of KAMS told

the committee that the National Suicide Prevention Trial needed to be more

responsive to the local factors, and that the trial is 'looking at evidence

from Europe, which senses depression as the centre of why people take their

lives, and all of the evidence in Aboriginal suicides says that it's not

depression; it's often all of the other crap that you're dealing with every

day.'[132]

4.128

Both KALACC and Aarnja sit on the National Suicide Prevention Trial

Kimberley community reference group. Both organisations discussed their

frustration with the project, citing a lack of progress and a lack of community

involvement in designing solutions:

All we get, as the community reference panel—they said,

'We'll set the strategic plan and we'll bring it back to you.' What did we get?

Two meetings in 12 months. No action. At the last meeting they came back and

said, 'We'll just give the money out.' As community organisation we thought we

were going to be consulted and involved in the establishment of the trial. It's

just gone to a fixed interest group. I will be blunt about it, because that's

what it is.[133]

4.129

Aarnja was so frustrated with the lack of progress and cultural

competence of the National Suicide Prevention Trial, they designed their own

suicide program, which is a family empowerment project for extended, rather

than nuclear, families and based is on Bardi and Jawi cultural frameworks.[134]

Inuit suicide prevention program

4.130

The high rate of suicide among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples is also found in other Indigenous peoples throughout the world.[135] The Canadian Inuit peoples' experience of colonisation is relatively comparable

to that of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, both historically and

also in the continued impacts of that colonisation in the form of collective

and intergenerational trauma and the destruction of the protective factors of

culture and a sense of identity.[136]

4.131

The following case study is of a suicide prevention strategy developed

for the Inuit Nunangat (homeland) regions in Canada by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami,

the national representational organisation of Inuit in Canada.

Case study: National

Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy

The National Inuit Suicide

Prevention Strategy (NISPS) envisions suicide prevention as a shared national,

regional, and community-wide effort that engages individuals, families, and

communities. The NISPS is a tool for assisting community service providers,

policymakers, and governments in working together to reduce the rate of suicide

among Inuit to a rate that is equal to or below the rate for Canada as a whole.

The NISPS will promote the

dissemination of best practices in suicide prevention, provide tools for the

evaluation of approaches, contribute to ongoing Inuit-led research, provide

leadership and collaboration in the development of policy that supports suicide

prevention, and focus on the healthy development of children and youth as the

basis for a healthy society.

Risk

factors for suicide

The NISPS identifies the key

risk factors for Inuit suicide as:

Historical Trauma: from the social and cultural upheavals tied to Canada's colonization of Inuit

Nunangat, experienced by an entire group as a result of a cumulative and

psychological wounding over a lifespan and across generations.

Social

Inequity: Poverty and other indicators of

social inequity translate into stress and adversity for families, disparities

in health status and increased risk of suicide.

Intergenerational

trauma: Unresolved symptoms of trauma can make

it difficult for caregivers to provide a sense of safety and security to their

children.

Childhood adversity: is linked to negative outcomes that are associated with suicidal behaviour,

such as poor mental health, substance abuse, and poverty.

Mental Distress: there are greater rates of depression, personality disorder and substance

misuse in Inuit who died by suicide.

Acute Stress: Mental

health disorders or developmental adversity impair an individual's ability to

cope with or adapt to life stress or change.

Strategy

The NISPS promotes an evidence-based,

Inuit-specific approach to suicide prevention by identifying priority areas for

intervention that would be most impactful in preventing suicide.

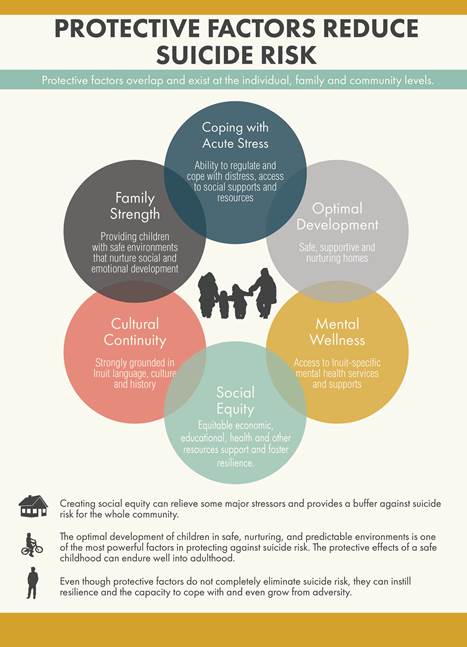

These priority areas are as

follows: (1) creating social equity, (2) creating cultural continuity, (3)

nurturing healthy Inuit children from birth, (4) ensuring access to a continuum

of mental wellness services for Inuit, (5) healing unresolved trauma and grief,

and (6) mobilizing Inuit knowledge for resilience and suicide prevention (see

Figure 4.2).

The Strategy's

evidence-based approach to suicide prevention considers the entire lifespan of

the individual, as well as what can be done to provide support for families and

individuals in the wake of adverse experiences that we know increase suicide

risk. Focusing our resources and efforts on supporting families and nurturing

healthy Inuit children is the most impactful way to ensure that people never

reach the point where they consider suicide.

Figure 4.2—Protective

factors identified by the Inuit suicide prevention strategy

Evaluation

One of the implementation

tasks will be to finalize an evaluation framework for the NISPS, by identifying

key indicators for each action item, and processes for collecting necessary

data in an ongoing way. Progress will be evaluated in two-year increments.

Source:

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy,

2016.

Committee view

4.132

The committee heard evidence from organisations and communities that

suicide, both attempted and completed, has long since reached a crisis level in

rural and remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. That this

has been allowed to continue unchecked for so long is to Australia's shame.

4.133

The committee heard overwhelming evidence from mental health experts

that in too many cases, the causes of suicide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples is not mental illness, but despair caused by the history of

dispossession combined with the social and economic conditions in which Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples live.

4.134

The committee strongly recognises the Australian and international

evidence that demonstrates the most effective suicide prevention strategies for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples will be to restore strong,

resilient communities who are able to raise children with the inherent

protective factors that arise from safe homes, safe communities and strong

culture.

National strategic framework

4.135

The Australian Minister's Health Advisory Council endorsed the National

Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples' Mental

Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017–2023 (Aboriginal Mental

Health Framework) in February 2017.[137]

4.136

The stated purpose of the Aboriginal Mental Health Framework is to 'to

guide and inform Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and

wellbeing reforms' and to 'to respond to the high incidence of social and

emotional wellbeing problems and mental ill-health [of Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples]'. The purpose also declares that ' the Australian

Government has committed to continue to seek advice from Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander mental health and related areas leaders and stakeholders to

shape reform at the national level.' [138]

4.137

The Aboriginal Mental Health Framework contains 5 key action areas, each

with three outcomes. Of particular relevance to discussions of culturally

competent mental health service delivery is the following action areas and

associated outcomes:

ACTION AREA 1: Strengthen the Foundations

Outcome 1.1: An effective and empowered mental health and

social and emotional wellbeing workforce.

Outcome 1.2: A strong evidence base, including a social and

emotional wellbeing and mental health research agenda, under Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander leadership.

Outcome 1.3: Effective partnerships between Primary Health

Networks and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services.

4.138

The Aboriginal Mental Health Framework notes that a monitoring plan

would need to be prepared, and noted it 'should be developed under the

leadership of, and in partnership with, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

leadership bodies.'[139]

4.139

CATSINaM recommended that all planning and development of mental health

services should follow the recommendations made in the Aboriginal Mental Health

Framework and the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan

2013–2023, both of which 'were for and about Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples and demonstrated best practice in policy development.'

CATSINaM noted however, that the Aboriginal Mental Health Framework did not yet

have an implementation plan and required associated funding investment.[140]

4.140

The following discussion outlines some continued policy and funding

concerns presented to the committee, which appear to show some inconsistency in

the early implementation of the Aboriginal Mental Health Framework.

Framework failures

4.141

A consistent theme appeared in the evidence presented to the committee,

that the lack of culturally competent mental health services for Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander communities was due in part to the fragmentation of

policy advice and funding arrangements across multiple jurisdictions. The

funding framework for mental health services was discussed in detail in chapter

two, including details on how the ACHHS sector is funded. This following

section will focus on certain policy and funding issues that continue to impact

the cultural competency of mental health services.

Policy fragmentation

4.142

The committee heard from a range of organisations that policy

fragmentation, across different geographical regions and different levels of

government, was a contributing factor to poor cultural competency of mental

health service delivery for rural and remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples.

4.143

NACCHO submitted that policy fragmentation is also felt in how services

operate, citing that a lack of coordination between government and

non-government services impacts mental health service provision, particularly

in addressing needs in a 'culturally appropriate and holistic way.'[141]

4.144

The Danila Dilba Health Service made an overarching recommendation that

all levels of government, as well as non-government service providers, should

adopt a policy to move services to the Aboriginal community-controlled sector,

starting with capacity building of the sector. This could be done by funding

for services to Aboriginal communities including a requirement for non-Indigenous

providers to develop an exit strategy and show progress in implementing that

strategy. Danila Dilba Health Service cited the Jesuit Social Services in

Victoria, who partnered with the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA)

and managed a successful transition in the roles where VACCA is now the led

agency in the partnership.[142]

4.145

When asked about this program, Jesuit Social Services told the committee

that organisations must be prepared to allocate enough time within the program

framework 'to enable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to strengthen

their capacity so that in the long term they may develop the autonomy and

skills required to manage these services.' Jesuit Social Services discussed a

similar approach they took to service delivery in Santa Teresa, and noted that

'Business-wise, that work is difficult because, when you're continually

operating to put yourself out of business, you have to work out how you stay in

business too.'[143]

4.146

CATSINaM submitted that many areas of policy, such as economic and

environmental policy, use impact assessments to predict and assess the

consequences of a proposed policy, to assist in creating better outcomes. CATSINaM

recommended that future policy decisions for mental health should include a

social impact assessment to study the consequences on Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples and all peoples in rural and remote Australia. CATSINaM

pointed to this being of particular importance for rural and remote Australia,

as the emphasis on market driven solutions for human services has resulted in

market failure in mental health services delivery in rural and remote

locations.[144]

Funding implications for cultural

competency

4.147

The committee was told that the complexity in funding arrangements for Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander-specific health and wellbeing services impacts on

the quality of those services.

4.148

NACCHO argued that the continual underfunding of ACCHSs to deliver

mental health and SEWB services limits the capacity of ACCHSs to improve the

mental health outcomes for Aboriginal people, leading to increases in hospital

admissions for complex and chronic conditions.[145]

4.149

Organisations from the ACCHS sector told the committee there was a

significant reduction in overall funding to the ACCHS sector after policy

oversight of Aboriginal-specific health and wellbeing funding was transferred

in 2013 from the Department of Health's Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Health to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.[146]

4.150

The committee was also told this transfer has resulted in increasing the

already confusing array of funding sources, which now includes the Department

of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Commonwealth health funding disbursed by PHNs,

as well as State and Territory funding. AMSANT recommended that at a

Commonwealth level, SEWB, mental health and AOD program funding be placed back

into the Indigenous Health Division of the Health Department, with input and

advice on funding decisions from jurisdictional forums such as the Northern Territory

Aboriginal Health Forum.[147]

4.151

The Northern Queensland PHN raised similar concerns, telling the

committee that multiple funding streams, not just in the health portfolio,

could be better coordinated to achieve improved outcomes with the same level of

resources.[148]

4.152

Danila Dilba Health Service commented that the fragmentation of funding

meant that an organisation could apply for capital works to build a facility,

but they did not guarantee funding would be supplied from different areas of

government to actually operate the service.[149] Danila Dilba Health Service also told the committee it takes a full time role

to apply for funding and then complete funding reporting requirements and they

had the capacity to do this only because they are a larger organisation.[150]

4.153

The Wurli-Wurlinjang Health Service noted that the funding fragmentation

of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing programs

sometimes led to the duplication of services. It also noted that this

ever-changing funding environment also meant that organisations have 'no real

foundation in regard to infrastructure to work from. There's no stability;

you're constantly on the move because it's so funding dependent.'[151]

4.154

AMSANT submitted that the small amount of overall funding available for health

and wellbeing services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples often

goes to large NGOs who lack local and cultural expertise. This leads to mental

health services designed and delivered without local Aboriginal input, which

are usually ineffective and inappropriate for Aboriginal communities and