Chapter 3 - Appropriateness of joint funding arrangements

Introduction

3.1

This chapter will examine the appropriateness or otherwise of the current

joint funding arrangements under the CSTDA and focuses on the overall structure

of the arrangements. Issues in relation to unmet need are discussed in Chapter

4.

3.2

Part 6 of the current CSTDA outlines the responsibilities of the parties

to the Agreement. All parties have continuing responsibilities under the

Agreement for funding specialist services for people with disabilities. While

funding responsibilities are shared between the levels of government, the CSTDA

divides the responsibility for funding specialist disability services from

their administration. The Commonwealth has responsibility for the planning,

policy setting and management of specialist disability employment services. The

State and Territory Governments have responsibility for the planning, policy

setting and management of specialist disability services except employment

services. These services include accommodation support, community access,

community support and respite care.

3.3

The Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments also share

administrative responsibilities for planning, policy setting and management of

advocacy services, print disability services and information services as well

as participating in and funding research and development.[1]

The current agreement expires on 30 June 2007; a fourth CSTDA is in the early

stages of negotiation.

3.4

As part of their joint funding responsibilities under the current CSTDA

governments have committed $17.1 billion over five years. There is roughly a

80/20 split between the funding contributions of the States and Territories Governments

and the Commonwealth for specialist disability services other than employment

services. For example in 2005-06 $3.552 billion was made available under the Agreement.

This was made up of $1.056 billion from the Commonwealth and $2.496 billion

from the State and Territory Governments. Of the Commonwealth's contribution, $450

million was spent on the provision of specialised disability employment

services and $605 million was transferred to the States and Territory Governments

for the provision of specialist disability services other than employment.

3.5

The Commonwealth makes CSTDA funding available as financial assistance

to the State and Territory Governments as a Specific Purpose Payment (SPP). In

the Agreement, this funding is described as the total amount required to meet

the Commonwealth's responsibilities for the management and administration of

all specialist disability services other than employment, 'a global amount to

be allocated on the basis of need' by the State and Territory Governments.[2]

The Commonwealth does not impose any requirements on the way funds are

allocated, except that they are used to fund services that are eligible for

funding under the CSTDA.

3.6

The Commonwealth's other contributions to people with a disability and

their carers are not included in the CSTDA arrangements. These include income

support payments such as the Disability Support Pension ($7.9 billion per annum),

the Carer Allowance ($1.1 billion per annum), the Carer Payment ($1.1 billion

per annum), the Mobility Allowance and the Disability Pension for Australian

Defence Force veterans. People with a disability may also be eligible to receive

Commonwealth-funded services through the Home and Community Care Program (HACC)

or other services and the Commonwealth Rehabilitation Service. Both these

programs are also not part of the CSTDA arrangements.

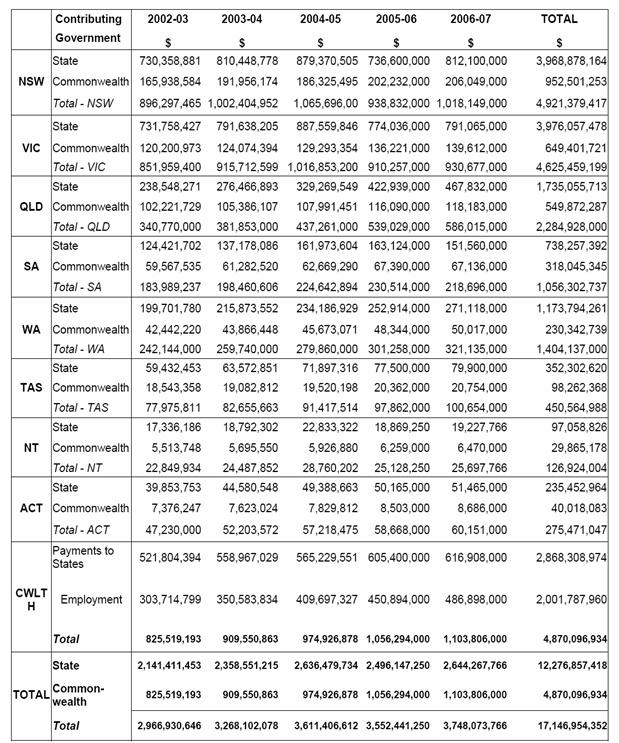

3.7

Table 3.1 is extracted from the CSTDA and provides the funding

contributed by each party.

Bilateral Agreements

3.8

The Commonwealth has signed individual bilateral agreements with each of

the States and Territories under the current CSTDA. Bilateral Agreements were introduced

under the second CSDA. The purposes of these Bilateral Agreements are to:

provide for action on strategic disability issues; provide a continuing

procedure for negotiation and agreement between the Commonwealth and individual

States/Territories on the transfer of responsibility for particular services

from one level of government to another; and to bring into the scope of the

CSTDA specialist disability services not yet included.[3]

3.9

In practice, the Bilateral Agreements provide the Commonwealth with a

level of influence over the provision of State and Territory disability

services. Bilateral Agreements also create a degree of flexibility to the joint

funding arrangements, providing the opportunity to address specific issues such

as increased access to respite care for older parents caring for their sons and

daughters with a disability or the transfer of services between the levels of

government.

Table 3.1: CSTDA funding

contributions by jurisdiction

Source: Commonwealth State Territory Disability Agreement 2002 -2007, Schedule A1.

Joint funding arrangements

Responsibilities

3.10

The previous and current agreements have been recognised as clarifying

administrative responsibilities between the Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments.

However, many submissions identified problems with the joint funding

arrangements of the CSTDA, in particular the lack of clarity regarding the shared

funding responsibilities and accountability. The lack of clarity regarding

responsibilities for funding disability services was highlighted as enabling

both levels of government to shift responsibility for the inadequate funding of

specialist disability services.

3.11

The CSTDA arrangements divide responsibility for the administration (the

planning, policy setting and management) of disability services from

responsibility for their funding. However, for the purposes of accountability

for service delivery these roles are linked. The inadequate provision of

disability services can result from either inadequate administration or

insufficient funding. Submissions also noted concerns about where

accountability rests in the division between funding and administration

responsibilities in the CSTDA.

3.12

Consistently submissions and witnesses expressed frustration at the lack

of clear accountability in the CSTDA arrangements.[4]

Ms Di Shepard submitted:

The current bureaucratic split between State and Commonwealth

allows for endless 'argy bargy' about who is accountable. The States say they

are doing their bit, but the Commonwealth is falling short. The Commonwealth

says just the opposite. Frankly, I don't care about playing the 'blame game', I

just want the system to work. It can't work properly until there is a fixed

point of accountability.[5]

Mr Richard Deirmajer commented:

One of the biggest issues we have also had between the states

and the federal government is that, when we lobby the state government... the

states seem to blame the federal government because they are not getting enough

funding. So we go and see the federal government, and they blame the states.[6]

Ms Deidre Croft in her submission stated:

The States and Territories Governments have consistently

maintained that the Commonwealth/States and Territories Disability Agreement

was based on a commitment to joint funding of disability support services. The

Australian Government, on the other hand, continues to assert that the funding

of disability support services (other than employment services) is a State and

Territory responsibility.[7]

3.13

However, the NSW Minister for Disability Services the Hon John Della Bosca

noted the advantages of State and Territory government administration of

services in allowing a level of local accountability in the provision of

disability services.

I think that in general the states—and I am speaking for New South

Wales—are better placed to facilitate local planning and community engagement

and to make sure there is local accountability to provide those services

directly. We are the people—in the case of New South Wales—who are already

running significant public services and facilitating the non-government

organisations to participate in our programs.[8]

3.14

Many submissions and witnesses identified specific criticisms with

individual State and Territory governments in relation to specialist disability

services. Ms Brown of the National Carers Coalition commented on the 'shocking

performance' of the NSW Government in provided adequate funding for disability

services in the past.[9]

NCOSS cited the comparable information listed in the Report on Government

Services produced by the Productivity Commission to identify a number of areas

where NSW has low proportions of people with disabilities using disability

services.[10]

The Disability Advocacy and Complaints Service of South Australia described

their advocacy efforts for individuals who had severe shortages in their care

hours and urgently needed aids and equipment:

We sent 76 individual letters to the Minister, the Premier and

the Treasurer of South Australia. Three years on half of the urgent needs have

been picked up, the other half are still waiting.[11]

3.15

There was overwhelming evidence that there is not enough funding for

disability services but some witnesses commented that they believed that there

could be more effective delivery of services at the State and Territory level.

Inflexible interfaces

3.16

The nature of the division of administrative and funding

responsibilities for specialist disability services to each jurisdiction and

level of government has lead to different approaches to the provision of

services. In some cases it has created program silos leading to inflexible

interfaces between disability services at each level of government or

jurisdiction. NCOSS in their submission emphasised that this frequently did not

result in optimal outcomes for people with disability or their carers:

Government funding programs stream people into designated

service categories, eg disability services, residential aged care facilities,

community care etc. This streaming can serve to reduce the desired flexibility

of service provision thus promoting a system which is driven by the service

system and not by individual needs. Clients are accepted because they "fit"

the service provision, not the other way around.[12]

UnitingCare Australia commented:

The current demarcation between jurisdictional responsibilities

means that people wishing to transfer between options or undertake a mix of

options are required to negotiate their way through two different service

systems with differing policy and funding priorities.

A need exists to simplify the system to make it easier for

consumers to access and navigate. This means ensuring that improved pathways

between Commonwealth and State funded services are two–way thereby enabling a

smooth transition into and between programs and services according to people’s

changing needs at different times and life stages.

Cross jurisdictional approaches to service provision need to be

further developed to encourage people to experiment with new or a mix of

options without risking the security of their placement.[13]

Commonwealth services -

State/Territory services interface - transitions

3.17

The problems of inflexible interfaces in the current system were

highlighted by Jobsupport Inc. While the cap on the Commonwealth funded

Disability Employment Network can prevent those persons capable and willing to

work from attempting to enter open employment, the State funded Post School

Options program also discouraged people from attempting open employment by

making it difficult to return after leaving the program.[14]

Jobsupport stated:

Firstly, the Commonwealth program is capped, so everyone who

wants to work cannot work, even if they are capable of doing so and it would

save the taxpayer money and, secondly, the state government in turn tends to

want to shut the door behind people. In our view, there is an opportunity to

actually save money, to let the people who want to work do so, and all we

really need to get it together is a more flexible interface between the two

levels of government.[15]

3.18

ACROD also noted that this interface was 'problematic' and 'fraught with

risk' for people with disabilities involved in employment transitions such as supported

employees seeking retirement or people moving from post-school option programs

to open employment.[16]

State/Territory services interface

– portability

3.19

A concern repeatedly raised with the Committee was the portability of

disability services and benefits to other States or Territories. Witnesses

expressed their frustration at the lack of consistency and equity in the availability

of services between jurisdictions. For example Mrs Jean Tops of the Gippsland

Carers Association stated:

'You are not a citizen of Australia. You are only a citizen of

the state in which you live'...If you leave Victoria, you cannot take any of your

services with you. You will have to start again on the waiting list in the

place you are going to get a service back. That ties families to the state in

which they live, to the region in which they live and to the services that they

currently have.[17]

3.20

In July 2000 a National Disability Administrators paper 'Moving

Interstate: Assistance to People with Disabilities and their Carers' in

relation to the portability of funding for disability services was endorsed at a

meeting of Ministers responsible for Disability Services. These recommendations

provided that: individuals seeking to move interstate may access that State or

Territory's service through transparent demand management processes based on

relative priority of need; individuals may register their request for service

prior to any planned transfer; and where the move is urgent, unplanned or due

to circumstances beyond the control of the individual, the State of origin

agrees to give consideration to the transfer of funds for up to 12 months.[18]

3.21

In practice these provisions do not appear to have provided a real

choice for people with disability who wish to move between jurisdictions. Mr John

Nehrmann of the Department of Health and Human Services in Tasmania commented:

In terms of clients or consumers there is a huge level of

uncertainty if you want to move. As I said, initially all you are getting is 12

months and then you have to hope you are getting the same level of service at

the same time. The other issue is that you are not always able to get the same

type of service from one jurisdiction to another. You might have an individual

funding program in one jurisdiction that allows you to buy certain services

that include certain things and yet when you move suddenly there are different

business rules and different things covered. Even though the program is roughly

the same, it is not quite the same.[19]

3.22

Ms Raelene West also indicated the current CSTDA funding framework was

'highly problematic' for people wishing to move jurisdictions:

Service recipients are often forced to renegotiate an entirely

new system of programs and services, and receive differing and often only

entitled to reduced levels of funded services if living in another

State/Territory other than original 'jurisdiction'.[20]

3.23

However there were also links made between the level of unmet need for

disability services and the lack of portability of services. Ms Lois Ford of the

ACT Government commented:

The assessment of need is based on the level of need the

individual has and the resources that we have available—and I would say this is

true for most states and territories—to meet that need. I guess that it is more

about meeting demand and growth within disability services so that people with

disability can transfer or shift from place to place like any other citizen. I

would suggest that it is less about the portability of funding and more about

demand for and growth of services in each area.[21]

3.24

While the problem of portability has been recognised in the past, moving

between jurisdictions is still extremely difficult because of the complexities

of needing to negotiate new services within a different system combined with

differing limitations on resources arising from underlying levels of unmet

need.

Recommendation 1

3.25

That State and Territory governments provide a specific service that

assists people with disability transferring between jurisdictions to negotiate

programs and services to achieve a comparable level of support.

Dual diagnosis and multiple

disability

3.26

The Committee was also concerned about implications of the lack of

flexible interfaces in the provision of services for people with disability

requiring services in relation to other health needs. Brightwater Care Group

commented:

Dual diagnosis is a challenge whether it is somebody who has

palliative issues, mental health issues or substance abuse issues—even if you

are Aboriginal, basically. As soon as you have an issue that puts you with a

bit of a foot in both camps, you find that neither camp wants you and can find

strong reasons for you to belong somewhere else. It is the need to break down

those jurisdictional boundaries and get agencies and funding organisations

talking to each other to see how to address the issues.[22]

3.27

However Dr Ken Baker of ACROD highlighted the problems facing service

providers caring for people with disability who also had other care needs:

People can rarely be neatly slotted into one box and not others...I

think the main complaint from among disability service providers is that they

are expected as disability service providers to respond to the total needs of a

person, and that is not really what they are equipped to do. They would have to

respond to a person’s mental health or drug and alcohol issues as well as their

disability rather than getting easy access to another system. In a sense, it is

an institutionalised view of governments that, once you are in the disability sector,

that is the institution that has to take total care of you. I think that is a

flawed view, but it is also, in a way, a dangerous view because it is

preventing a person from getting access to other service systems which ought to

be responsive to their disability.[23]

3.28

Mr Arthur Rogers of the Victorian Government commented on the definition

of disability in the Disability Services Act 2006:

Certainly in our operational practice there is no impediment to

people, as long as they have a disability within the meaning of the Act. So if

they had a mental illness they would not get in, but if they had an

intellectual disability and a mental illness we would cover them for the disability.

Part of the difficulty around service provision is that where

people have multiple disabilities they have complex support needs and they do

not fit into some of the more generalist services. By 'generalist' I mean a

house catering for people with an intellectual disability. A person with an

intellectual disability and a mental health issue and maybe a physical

disability has quite specific needs. You need to make sure that the service

response is tailored to those needs, not just to intellectual disability. So I

think the issue is the complexity of their support needs rather than the

definition in the Act.[24]

3.29

There appears to be two problems emerging in relation to the recognition

and support of people with dual or multiple disabilities: the first is where

the interaction of multiple disabilities means that existing programs and

services are ill-equipped or unable to meet the complex, higher level needs of

a client; the second is the issue of 'handballing' where existing programs or

services are suggesting the existence of a second disability is an excuse to

pass-the-buck to another program or service and effectively deny support. There

is also a clear need to provide appropriate specialised services.

Recommendation 2

3.30

That the next CSTDA clearly recognise the complex and interacting needs

of, and specialist services required by, people with dual and multiple

diagnosis, and people with acquired brain injury.

Complexity and overlap

3.31

The division of funding and administrative responsibilities between the

Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments creates overlap and duplication

in bureaucratic and administrative arrangements for the provision of disability

services as well as a lack of uniformity and equity between jurisdictions. In

her submission Ms West commented:

Each of the States/Territories 'jurisdictions' continue to fund

disability services at different rates and with differing levels of

accountability. Each State/Territory is governed by differing legislation with

differing obligations and priorities to users. This is despite a national

population of only 20 million people and with only a relatively small

percentage of this population utilising some form of funded disability service.

Under the current form of CSTDA funding, each state continues to roll out their

own gamut of programs, services, strategies and policies, creating further

inequities in the system on a national level. Service delivery on the ground

therefore continues to be disparate, with real mapping and contrasting of

service delivery remaining difficult.[25]

3.32

The complexity in the arrangement under the current CSTDA also causes additional

burdens for disability services users. Ms Teresa Hinton of Anglicare Tasmania,

who had recently completed a research project on disability services, commented

on difficulties with the fragmented nature of services.

To receive personal care and support, somebody might be dealing

with three or four different agencies, each with their own assessment process,

different disability support workers and so on. Being able to coordinate that

for individuals was very problematic and difficult for them, for individuals

and also carers who might have been taking on the case management role.[26]

Cost-shifting

3.33

During the inquiry a number of issues regarding cost-shifting between

the levels of government were raised. Cost-shifting may occur where funding

arrangements allow responsibility for services to transfer to a program funded

by another party without their agreement. The complex arrangement of the

division between the levels of government of responsibilities in relation to

areas which overlap with disability such as health, ageing, employment and

education may provide opportunities and incentives to shift the costs of

service delivery. Cost-shifting between governments can also contribute to

problems such as accountability for disability services.

3.34

ACROD encapsulated this issue by stating in its submission that:

For governments, funding is clearly a contentious issue. In the

past, negotiations have been marred by suspicions of cost-shifting and

accusations from each level of government that the other provides less than its

fair share of funding for State-administered services.[27]

3.35

The Commonwealth pointed to an increased usage of services under the

Home and Community Care (HACC) program by people with disability.

People with disability are estimated to comprise over 24 per

cent of the total number of HACC clients. However, they are estimated to

consume 30 per cent of the funding because proportionately more people

with disability access higher levels of service.

The proportion of younger people (those under 65 years)

accessing HACC services has increased from 18.5 per cent in 1994-95 to over 24

per cent in 2004-05. Given that the percentage of young people in the general

population has declined over the same period, the growth in young people as

HACC clients suggest that outside of HACC, disability services delivered by the

states and territories have not grown in line with demand.

CSTDA data indicates that there has been significant decline in

the number of service users aged 60-64 years compared to those aged 55-59 years

across all CSTDA funded service types...There is a concern that this decline

reflects a trend for older people with disability ending up in inappropriate

aged care or hospital services due to a lack of appropriate disability

services.[28]

3.36

Ms West also identified that shortfalls in State and Territory disability

services had "forced" people with disability to utilise HACC program

services.

Ideally, a significant expansion and increase in funded

disability services could move people requiring disability services off HACC

funding and onto specific disability support programs and funding arrangements

alone, increasing clarity of service need and providing specialised disability

support.[29]

Whole of government coordination

3.37

The need for better coordination between Commonwealth, State and

Territory jurisdictions and departments was also raised with the Committee. The

responsibility for ensuring that Commonwealth and State/Territory programs are

having a complementary impact is shared by all the parties in the current

CSTDA.[30]

Ms Lyndall Grimshaw of Brain Injury Australia commented:

If we look at government policy and program development, what we

see is fragmentation and program silos...There is little evidence from our

perspective of interdepartmental cross-policy program collaboration, both

across and between the Commonwealth and state and territory levels.[31]

3.38

The point was made that despite the interrelationships in the services

covered by the CSTDA, such as health and employment, the only Commonwealth

Department a party to the Agreement was the Department of Families, Community

Services and Indigenous Affairs ( now FaCSIA). The Department of Health and

Ageing and the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations have not been

parties to the CSTDAs. ADFO for example commented:

A major barrier to the effective oversight of progress towards

the achievement of the aim of the CSTDA has been that no single agency has been

given the task and authority to do this. At a Commonwealth level alone, direct

services to people with disability are provided by at least seven departments

and most of these are not involved in the Agreement.[32]

3.39

In 2004 responsibility for administration of open employment services

operating under the CSTDA moved from the Department of Family and Community

Services (now known as FaCSIA) to the Department of Employment and Workplace

Relations. Supported employment services for people with disability continue to

be administered by FaCSIA. MS Australia commented that as a result of this

change:

FaCSIA remains the lead Agency at the Australian Government

level in regard to disability services despite being the smallest and least

involved agency in the delivery of disability services. This is a situation

that has definitely hindered development of the sector, due to its inability to

lead and champion disability issues across Australian Government portfolios

including employment, education and health.

This problem is mirrored in the States where key areas such as

infrastructure, transport and health are not directly included in the CSTDA

work of the lead disability departments who are CSTDA signatories, and where

the general policy response is limited.[33]

3.40

ACROD commented:

Governments are hierarchical entities. If a whole of government

approach is to be effective it needs to become a priority of central government

agencies and, ultimately, requires leadership by the heads of government.[34]

3.41

The Mid North Coast Disability Committee also suggested there is potentially

a greater role for local government in the delivery and co-ordination of

specialist disability services.[35]

3.42

Governments are working at improving the coordination of disability

services. At the July 2006 meeting of the Community and Disability Service's

Ministers' Conference, Ministers agreed on three priority areas of shared

concern that would likely benefit from national collaboration for a fourth

CSTDA. These were service improvement, demand management and interface issues.[36]

A national approach?

3.43

The argument was made to the Committee in a number of submissions that

problems associated with the CSTDA joint funding arrangements may be addressed

if the Commonwealth assumed sole responsibility for funding of services in

relation to disability.[37]

These arguments reflect long-standing and on-going debates regarding the

balance of Commonwealth, State and Territory responsibilities for Australia's

health care system and the issue of cost-shifting.[38]

3.44

A Commonwealth 'take over' of disability services was seen as broadly

addressing a number of perceived systemic problems with the current joint

funding arrangements. These included greater accountability, a uniform approach

service delivery, the more equitable allocation of disability services and

improved co-ordination across service systems. Ms West elaborated on the

advantages of a national approach in her submission:

Benefits would appear to be considerably improved

standardisation and uniformity in the level of funded disability service

programs, increased coherency and consistency of available services and clearer

expectations for clients as to available services and resources. In terms of

administration, a national approach would significantly reduce as previously

highlighted, difficulties with managerial assessment, contrasting accounting practises

and data collation and analysis.[39]

3.45

Submissions, particularly from the Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments,

while acknowledging problems existing in the current system, emphasised the benefits

of joint funding arrangements. They noted that the CSTDAs have been successful

in ensuring that all jurisdictions have specific funding available for people

with disabilities and that where jurisdictions are clear on their responsibilities

and sufficient funding is made available there have been significant outcomes

for people with disabilities.[40]

For example the Western Australian Government commented:

The CSTDA has allowed the Commonwealth, States and Territories

to maintain a focus on disability and direct resources specifically to meeting

the needs of Australians with a disability to an extent that was not occurring

before the existence of these agreements. While that in itself should not be

held as the only argument for the continuation of the multilateral agreements,

it is strong evidence in support of specific collaborative funding arrangements

for disability services.[41]

3.46

Similarly the National Ethnic Disability Alliance noted that 'Commonwealth

and State/Territory joint responsibilities in funding and providing disability

services should be maintained for better accountability and Commonwealth/State

coordination'.[42]

3.47

ACROD also noted the serious weaknesses in the CSTDA but continued to

support a joint arrangement. Dr Baker commented:

...we support governments negotiating a fourth Commonwealth

State/Territory Disability Agreement. We think that the original CSTDA was an

improvement on the system it replaced, and there have been some subsequent

improvements. Having said that, we believe that the fourth agreement ought to

be substantially reformed...[43]

Competitive federalism

3.48

An issue which was not discussed in many submissions was that of

competitive federalism. The decentralisation of responsibility for disability

services to the State and Territory Governments provides them with flexibility

to address local issues and increased opportunities for innovation in policy.

It also provides a competitive environment where the best policies once

introduced and tested by one jurisdiction can be adopted by other

jurisdictions. State and Territory Government policies in relation to

disability services are comparable which creates a competitive pressure on

underperforming jurisdictions to match the 'best practice'. NSW Minister for

Disability Services the Hon John Della Bosca commented:

I am a fan of competitive federalism. That might sound like a

very old-fashioned idea but I think there is some merit in the idea of six

different systems in a range of areas, provided there is a reasonable

harmonisation...[44]

A federal dilemma

3.49

In 2005 the Productivity Commission conducted a Roundtable on

'Productive Reform of the Federal System' which focused on issues associated

with the challenges of securing better policy outcomes from Australia's federal

system of government and included some examination of options for systemic

change in health reform.[45]

Some of the discussion is readily applicable to consideration of the CSTDA

joint funding arrangements.

3.50

A key feature of the current federal system in Australia is that the

States have broad spending responsibilities but few revenue sources whilst the

reverse is true at the Commonwealth level. The difference between the relative

revenue and spending responsibilities of the Commonwealth and States is known

as vertical fiscal imbalance.[46]

In the CSTDA the State and Territory Governments contribute the majority of

funds for specialist disability services other than employment and have

administrative responsibility. However because of factors relating to vertical

fiscal imbalance and recent budget surpluses the Commonwealth was perceived by

some as having a greater financial capacity than the State and Territory Governments

to fund specialist disability services and swiftly address unmet need.

3.51

A number of possible options for health reform were identified by Mr Andrew

Podger. These options included: the States taking full responsibility for

health and aged care services; the Commonwealth taking full financial

responsibility for health care; the Commonwealth and States pooling their funds

as regional purchasers; and a 'managed competition' model where Commonwealth

and State funds are available for channelling through private health insurance

funds by way of 'vouchers' which individuals may pass to the fund of their

choice.[47]

3.52

Mr Podger's view was that it was feasible for the Commonwealth to take full

financial responsibility and identified a number of the possible benefits of

such a proposal. These included allowing a single Commonwealth minister and

department to control the national management and delivery of services. This

would increase accountability for services and operate to reduce cost-shifting

and duplication. Such an approach would also address the problems created by

vertical fiscal imbalance by having the revenue raiser as the primary purchaser

of services. It would also reflect a trend towards increasing Commonwealth

control over health care.

3.53

However, Mr Podger also noted costs and risks in a Commonwealth 'take

over' of health services. It would require significant expense and a lengthy

transition period for the Commonwealth to take over control of State and

Territory personnel and facilities as well as to establish new administrative

structures which allowed for regional and community flexibility and input. The

proposal would also involve complex renegotiation of current tax revenue

arrangements.

3.54

In 2006 the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and

Ageing tabled The Blame Game: Report on the inquiry into health funding

which also examined proposals for reforming federal arrangements in relation to

health care.[48]

A key recommendation from this report was that Australian governments

develop and adopt a national health agenda. Part of the proposed national

health agenda would be to identify policy and funding principles and

initiatives to: 'rationalise the roles and responsibilities of governments,

including the funding responsibilities, based on the most cost-effective

service delivery arrangements irrespective of governments' historical roles and

responsibilities'.[49]

Conclusion

3.55

The current and previous Agreements have demonstrated a commitment on

the part of all Australian governments to ensure that resources are specifically

allocated for the provision of specialist services to improve the lives of

people with disability.

3.56

The Committee supports a fourth disability agreement between the

Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments. The State and Territory Governments

continue to have the service delivery expertise and can be more responsive to

the needs of people with disability and carers within their jurisdictions.

3.57

However there is clearly a need for improvement in consistency, equity,

coordination of specialist disability services as well as accountability,

performance monitoring and reporting. In these areas the Commonwealth is best

placed to perform a leadership role. The Commonwealth also possesses the

capability through the Bilateral Agreements to achieve better results in these

areas.

3.58

The Committee notes that the ANAO audit of the administration of the

CSTDA found evidence that the Bilateral Agreements had improved coordination

with relevant State and Territory Government disability agencies and considered

the Bilateral Agreements have the potential to be an effective coordination

mechanism for the Commonwealth's lead agency to work with State and Territory

agencies.

3.59

The Committee notes that Bilateral Agreements between the Commonwealth

and State and Territory Governments for funding of disability services will

often necessarily affect the provision of other disability services as well as

other publicly funded services. Where possible Bilateral Agreements should not

skew or distort the broader objectives of the CSTDA.

3.60

The Committee also notes that the Commonwealth may potentially have more

capacity to control and co-ordinate disability services if it increased the

proportion of Commonwealth funding to CSTDA services. ANAO also noted:

The fact that the Australian Government only provides 20 per

cent of the funding for services administered by the States and Territory

governments limits its roles, and the amount of influence it has over the

delivery of those services.[50]

3.61

The Committee recognises that the present funding arrangements assign

the States and Territories the primary responsibility for funding specialist disability

services and the Commonwealth responsibility for funding disability employment

services, with some Commonwealth supplementation of the States and Territories'

role. However these arrangements are problematic, and have generated

considerable uncertainty within the disability community about where services

can be found, what criteria for eligibility apply and which government bears

responsibility for its proper funding. The next CSTDA must as a priority,

remove this uncertainty and create transparent lines of responsibility.

3.62

Options for large-scale reform to the current CSTDA joint funding arrangements

may offer more challenges than solutions. The Committee recognises that any

reform is not without cost or risk and that any new arrangement or division of

responsibilities will necessarily involve some service delivery problems. Any

major change to the structure of joint funding arrangements under the CSTDA

should be accomplished as part of a broader restructure of Commonwealth, State

and Territory health and community care responsibilities.

3.63

However despite these concerns the Committee agrees the CSTDA could be

utilised more broadly to improve the lives of people with disability. The

Committee supports the AFDO's comment that:

...the CSTDA is far from being a coordinated, high level strategic

policy document. Despite its broad aim and the priority placed on access to

generic services, the current CSTDA retains a narrow focus on service delivery,

particularly disability-specific services, to people with disability aged under

65 years. The CSTDA is crisis driven, with the result that short-term,

individually focussed interventions are prioritised over systemic reforms.[51]

3.64

A renewed national disability strategy could function to coordinate the

objectives of the Commonwealth Disability Strategy and the disability policy

frameworks which have been developed by many of the States and Territories,

such as Victoria's State Disability Plan. By providing a coordinating framework

for various policies, programs, legislation and standards the next CSTDA may

enable effective responses to be developed to the complex issues which people

with disabilities face.

Recommendation 3

3.65

That the next CSTDA should include –

- A whole of government, whole of life approach to services for

people with disabilities.

- A partnership between governments, service providers and the disability community to set policy priorities and improve

outcomes for people with disability.

- A clear allocation of funding and administration responsibilities

based on the most effective arrangements for the delivery of specialist

disability services.

- A clear articulation of the services and support that people with

disability will be able to access.

- A commitment to regular independent monitoring of the performance

of governments and service providers.

- A transparent and clear mechanism to enable people with

disability and their carers to identify and understand which level of

government is responsible for the provision and funding of services.

Recommendation 4

3.66

That in the life of the next CSTDA, signatories agree to develop a National

Disability Strategy which would function as a high level strategic policy

document, designed to address the complexity of needs of people with disability

and their carers in all aspects of their lives.

Assessment

Assessment and planning

3.67

The Committee was concerned at the apparent lack of connection between

assessments being undertaken and the planning by governments for the needs of

people with disability. Assessments would seem an appropriate method for

governments and service providers to budget and plan services as well as to

give people with disability and their carers a level of certainty. Mrs Franklin

highlighted the approach taken by the United Kingdom to lifelong assessment and

planning.

When the child is born or diagnosed with a disability, you are

assessed and they put a care package together. Then they reassess it when the child

is going to school and they either take some of that care package off them or

add to it, depending on the disability. Then at the end of primary school they

are reassessed. Two years before they leave high school they are assessed, and

what they look at there is accommodation and employment—all of that.[52]

3.68

This approach could be contrasted with the experience of many Australian

families. Ms Allen commented:

The maze to find services was an absolute nightmare and actually

was the most energy-zapping situation that you can imagine. Rather than having

that time to give to my child, I found myself fighting the bureaucracy almost

every minute of the day. There was no plan for us and there was certainly no

plan for Simon. We had to negotiate for everything that we got. We had to

emphasise the negative the whole time. We had to make it sound actually as bad

it was and it was very hard for people to actually realise what we were going

through.[53]

Application procedures

3.69

Another assessment issue raised was the procedures involved in the

applications for State and Territory disability services. While practices

differ between jurisdictions these application and eligibility procedures often

rely on people with disabilities or their carers filling out detailed forms

setting out their circumstances and needs in order to be assessed for eligibility

and access to disability services. These forms are then assessed on a

competitive or criticality of needs basis to determine who has access to disability

services.

3.70

These can be highly distressing for families members required to

describe a loved one negatively, focusing on how caring for their needs is a

burden to them.[54]

People with disability and their families are also forced to 'compete' for the

available disability services against other equally deserving families. Ms Croft

commented:

I think there are a number of consequences of having a competitive

or criticality of needs basis for service provision. One is that family carers

are required to portray the needs of their family member with a disability in

the worst possible light, as being a burden on them and their family, and I

think that has enormous implications. There is a risk of devaluing people with

disabilities. I think also it requires an enormous bureaucracy to supervise who

gets funding on whatever level of critical need, so providing services on the

basis of pitting people’s needs against each other consumes resources and has

an effect even in terms of simple human dignity. I hear so many parents

expressing views about having to compete against people that they recognise are

also experiencing great hardship. They feel guilty about that. But also it is a

matter of who can demonstrate that their crisis is worse than someone else’s

crisis, which is not a dignified way in which services should be provided. It

also means that we have lost sight of the rights and needs of people with

disabilities and instead we are focusing solely on how healthy or strong their parents

or their carers are...[55]

3.71

The Committee is also concerned that some assessment procedures for

access to disability services appear reliant on written applications. These

procedures disadvantage people with poor literacy or communication skills,

often the people in the most need of assistance. An example given by Mrs Franklin

from Committed about Securing Accommodation for People with Disabilities (CASA)

highlighted this concern:

I have been helping a family—a Vietnamese lady; she has a son

with severe disabilities, her husband is dying of cancer and another son has

had kidney transplants. Because she cannot articulate on a piece of paper and

because of her cultural background—she does not like to ask for help—she keeps

getting knocked back in the funding round. If a team had gone out and assessed

the child with the disability and looked at the family in general she would

have got funding a long time ago.[56]

3.72

The Committee was interested in the potential benefits of utilising

information technology and the internet to reduce the burden that people with

disability and their carers carry in relation to communicating their needs to

services providers. An Adelaide based disability organisation 'Life is for

Living Inc' are currently running a project 'What I'd Like You To Know About

Me!'[57]

The project created a CDROM resource kit for service providers that focused on

capturing holistic and positive information about people with disabilities. The

information collected by the resource could then be printed and shared with

others such as family and friends, teachers, therapists, health professionals

and community members.[58]

For example, "Who are the members of my family?" "When

I go to hospital, I need this," "This is how I like to be cared for",

and "These are my favourite toys." It is written from the perspective

of the person with the disability. It empowers the family and the person with

the disability to put their own story forward. It can be used by health

services and other service providers to talk to the child when they are in

hospital, for example.[59]

A National Framework

3.73

The ANAO audit of the administration of the CSTDA noted that:

The States and Territories, and the Australian Government, have recognised

that there: "is currently no one conceptual model adopted by jurisdictions

that assesses eligibility, support needs and priority for service at both a

systemic and individual level".

This situation has resulted in a lack of national consistency in

how individuals’ needs for services are identified and in determining priority.

The ANAO considers that, in this circumstance, there is a significant risk that

services provided under the CSTDA may not be provided to those recipients in most

need across Australia.[60]

3.74

Carers Australia also highlighted the need for national consistency in

assessments of eligibility, support needs and service priority.

Carers Australia believes that the new CSTDA should include a

national framework for the provision of services to meet the needs of people

with disabilities in Australia. Such a framework should take a holistic

approach to the needs of the person with a disability and their carer, and be

based upon person-centred assessment. It should also recognise that many people

have more than one disability and different services are often required to meet

these different conditions.[61]

3.75

The National Disability Administrators Research and Development Program

was undertaking a project National Assessment and Resource Allocation

Framework with the purpose of developing 'a flexible, nationally-consistent

system which ensures a fair, transparent, consistent and rationale-based

allocation of resources that will also assist in understanding and managing

demand for disability services.' The Committee understands this project has now

been cancelled.

A Disability Assessment Team?

3.76

A key issue for the Committee was the importance of assessing the needs

of people with disabilities. Without an accurate and comprehensive assessment

of the care and support needs of each individual it seems impossible to

determine which specialist disability services or other services they should be

able to access. This basic information also appears crucial to a number of the

other issues raised in the inquiry.

3.77

Accurate and comprehensive assessments of the needs of each individual

with a disability could assist in:

- tailoring available services to meet an individual's specific

needs rather than fitting people to services or programs;

- enabling governments to plan services and funding by clarifying

the needs of people with disabilities in their jurisdiction;

- preventing cost-shifting between the levels of government by

independently assessing the services a person should be able to access;

- informing people with disabilities about the services which they

are eligible to access and facilitating access to those services;

- determining eligibility and priority through an equitable process

to ensure resources are delivered to those in the most need as well as reducing

the burden on family carers in making applications for services

- collecting additional data concerning unmet need in each

jurisdiction as well as making governments accountable for inadequate funding

or provision of specialist disability services; and

- recognising and addressing the special needs of people with dual

and multiple diagnoses.

3.78

The approach of the Aged Care Assessment Teams (ACATs) involving

face-to-face comprehensive functional assessments of individuals was generally

supported during the inquiry. ACATs are multi-disciplinary and can include

health professionals such as medical officers, social workers, nurses,

occupational therapists and physiotherapists. The objective of the Aged Care

Assessment Program is to 'comprehensively assess the needs of frail older

people and facilitate access to available care services appropriate to their

care needs.' Proposals were raised for a similar approach to assessments for

people with disabilities and their access to services.

Recommendation 5

3.79

That the next CSTDA incorporate a nationally consistent assessment

process to objectively and comprehensively determine the support and care needs

of each person with a disability. These assessment processes should also assist

people with disability by making determinations of eligibility for services and

priority of need as well as facilitating access to appropriate services.

The burden of multiple assessments

3.80

The Committee was concerned to hear of the issues people with

disabilities and their carers had with assessment procedures for access to

disability services. A common complaint was the need to continually repeat

information regarding disability care needs to service providers and care

workers or to frequently attend assessments in order to access disability

services. This was particularly burdensome for people with permanent lifelong

disabilities and their carers. Ms Stagg explained to the Committee some of the

challenges of caring for her daughter Michelle:

All I want is a piece of paper that says, "Has anything

changed?"—"No," tick, the doctor signs it and you go. That sort

of stuff is frustrating all the time...Somebody who starts this from birth has to

go through that again and again...I really do not know how you are going to get

away from that, but there must be some way of facilitating people from day dot

to help them through the system...[62]

3.81

Mrs Griffin repeated these concerns regarding assessment procedures in

relation to her son Scott:

One of the things that I find most frustrating is being sent

forms continuously and having to restate that nothing has changed with Scott.

The fact is that nothing is going to change. He is not going to suddenly get

better. He has a genetic deletion that is there and will be there and is never

going to change, so his needs are always going to be as they are, if not worse

as he ages. It would be nice if some of that could be understood so that it was

broader than a particular disease. It needs to be understood so that once a

person is diagnosed with something like a genetic deletion that is never going

to change you do not have to spend your whole time begging for equipment or

begging for help. It should be on record that this child needs help ongoing,

long-term, until the day he dies.[63]

3.82

This issue appeared to be the result of the complexity of the

administration disability services as well as inefficient assessment procedures

and information sharing by disability providers and agencies. This is an issue

complicated by administrative requirements and by privacy laws designed to

protect the private health information of all Australians. The Committee agrees

that people with permanent lifelong disabilities and their carers should not be

required to repeatedly 'prove' their disability in order to obtain disability

services. Where possible they should be given the choice to consent to their

assessment information being shared and utilised in the most administratively

effective fashion.

Appropriate Assessment

3.83

The specialised assessment needs of people with chronic degenerative

diseases such as Motor Neurone Disease and Multiple Sclerosis were also raised

with the Committee. The degenerative nature of these conditions means the

assessment of current and future need for disability services was problematic.

Changes in their needs for disability services and equipment were often sudden

and unpredictable. Long waiting periods for assessment and access to services

was inappropriate for the changing nature of their conditions.

Recommendation 6

3.84

That the Commonwealth, State and Territory governments ensure that:

- administrative burdens of assessment procedures are reduced for

those with lifelong and permanent disabilities and their carers; and

-

flexible assessment options are available to people with

disabilities who have needs that may change rapidly.

Indexation of CSTDA funding

3.85

A number of submissions raised the issue of indexation of CSTDA funding,

particularly in relation to Commonwealth contributions.[64]

Indexation (or price adjustment) is intended to change funding to take account

of changes in the cost of services over time so that providers can continue to

offer the same services.

3.86

Part 8(10) of the current CSTDA provides that indexation of Commonwealth

funds to be transferred to the State and Territory Government are calculated

each year by reference to the Commonwealth indexation parameter Wage Cost Index

2. The Commonwealth indexation of CSTDA funding based on Wage Cost Index 2 was

2.1 per cent for 2005/06 and 1.8 per cent for 2006/07. The decision about

which indexation rate is applied to Commonwealth CSTDA funding is made by the

Department of Finance and Administration. The State and Territory Government

indexation of their CSTDA funding varied.

3.87

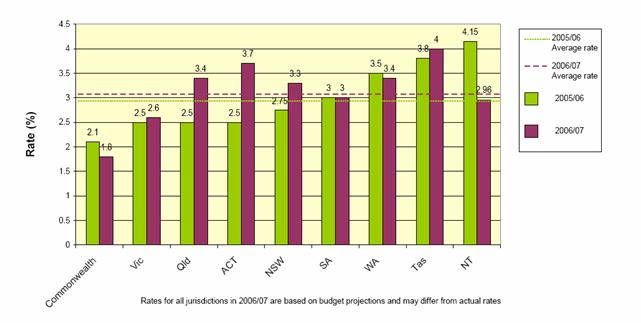

Table 3.2 outlines the indexation rates applied to CSTDA funding by each

jurisdiction.

Table 3.2:

CSTDA indexation rates by jurisdiction 2005/06 and 2006/07

Source: Western Australian Government, Submission 3,

p.18.

3.88

Many submissions to the Committee argued that the Commonwealth's rate of

indexation was unrealistic and insufficient to keep up with increased costs

(particularly wages) in the disability sector. The consequences of indexation

rates applied to CSTDA funding which did not reflect increases in costs in the

provision of disability services were also highlighted. In particular an

inadequate rate of indexation applied to CSTDA funding could gradually erode

the real value of the base funding and affect the viability and sustainability

of disability services.

3.89

NCOSS stated in their submission:

Certainly, previous indexation rates have not compensated for

increases in costs, including wages, activities and overheads, as well as

external impacts such as insurance, workers compensation and fuel prices etc.

This has resulted in a pattern of consistent underfunding with the net effect

being diminished service capacity.[65]

3.90

Dr Baker from ACROD identified the problems that inadequate indexation

of CSTDA funding could cause for disability service provider staffing:

The cumulative effect of this gets worse and worse as time

proceeds and makes it more and more difficult for disability service providers

to recruit and retain staff. This has now reached quite critical levels within

the sector...we need first of all to provide service providers with enough

capacity to recruit, train and retain quality staff. That cannot be achieved

while they are having to manage what is in effect an annual funding cut.[66]

3.91

Some State and Territory Governments argued that the level of indexation

applied by the Commonwealth to CSTDA funding has operated to gradually shift

the funding burden to them. The Queensland Government also highlighted the

Commonwealth's application of different indexation rates in relation to other

social program funding.

The Home and Community Care Program, for example, has a range of

indexation rates varying between 2.1 per cent and 3.85 per cent applied

annually. The Supported Accommodation Assistance Program has an indexation rate

of 2.2 per cent, while the Australian Healthcare Agreement also has varying

indexation rates. Its general component is made up of two per cent wage-cost

indexation and 2.84 per cent population growth. Seventy-five per cent of the

general component comprises 1.7 per cent utilisation growth.[67]

3.92

However FaCSIA indicated that the Commonwealth was not merely seeking to

address increased costs in the delivery of disability services in setting the

indexation rate. Consideration of the Commonwealth's indexation in relation to

CSTDA funding should also take into account additional funding initiatives made

by government. Mr Stephen Hunter of FaCSIA commented:

The government does not seek, through indexation, to cover all

cost increases that might occur in the delivery of a service. If it were to do

that there would be very few incentives to seek to contain some of the costs.

What it seeks to do through indexation is to ensure that the forward estimates

broadly reflect the price basis of the year in which the expense is to occur

and the minimal realistic costs of delivering policy outcomes. So it does not

try to compensate for actual movements in costs but rather to, in the broad,

ensure that the forward estimates reflect the price basis of the units involved...I

think when you look at the issue of indexation alongside the other additional

funds that have been put forward in the context of the CSTDA, that is a

relevant consideration. If, simply, you just compensate for all the cost

increases that might occur, governments then to an extent rob themselves of the

capacity to make specific initiatives which might go to achieve specific

outcomes.[68]

3.93

The Department of Finance and Administration has also indicated that

Wage Cost Index 2 has been used as the indexation rate for Commonwealth CSTDA funding

as the relative weighting of wage and non-wage costs best reflects the balance

between wage and non-wage costs in the services supplied under the CSTDA.[69]

3.94

However in 2002, the Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC) conducted a

study for the National Disability Administrators which examined the issues of

indexation and demand in relation to CSTDA funding. It suggested that Wage Cost

Index 2 was not suitable for CSTDA indexation as the method of calculation was

not appropriate for the disability sector:

Wage Cost Index 2 is based primarily on the Industrial Relations

Commission Safety Net Increase together with a small component based on general

price inflation. This is so the index should not include any component of wage

growth that is intended to be offset by efficiency gains. However, this implies

assumptions about productivity growth that are not in accord with generally

accepted economic principles. Economic theory suggests that wage growth in

service industries and human services in particular, will run well ahead of

productivity growth in that sector.[70]

3.95

This view was supported by the Queensland Government which commented:

Indexation models adopted by the Commonwealth Government have

been based upon the assumption that there will be efficiency dividends or

productivity saving that result in reduced labour costs or efficiencies due to

technology or telecommunications improvements. However research has found that

industries such as human services are not able to make productivity gains in

ways that are available to other industries. This is due to the fact that they

are highly labour intensive, have limited opportunities for technology-based

productivity gains, experience significant flow-on pressures for wage increases

from allied sectors and are expected to meet prescribed service delivery

standards.[71]

3.96

Dr Baker commented:

There is an assumption built into the Commonwealth indexation

formula which is just flawed. It may be appropriate for a manufacturing sector

or a mining sector, where human resources can be replaced with technology and

productivity can be achieved like that, but that is not true within the

disability sector, where social interaction is the nature of the business.

Disability support workers cannot be replaced by machines. The assumption

within the Commonwealth indexation formula that any increase that is over and

above the safety net increase can be traded off against productivity or

efficiency increases is just not true.[72]

3.97

The Committee considers that the application of the efficiency dividend is

generally inappropriate in relation to the indexation of funding for specialist

disability services given the necessarily high proportion of total budget which

must be spent on staff wages in delivering personal care. Recognising that

limited efficiencies can be gained in the sector, the efficiency dividend

effectively acts to cut the level of funding for disability services.

Recommendation 7

3.98

Given the reality that a large proportion of costs in disability

services will always be wages and salaries of care providers, the Committee

strongly recommends that the Commonwealth consider removing the efficiency

dividend from the indexation formula for funds allocated through the CSTDA.

3.99

The SPRC study recommended an indexation rate based on actual movement

in wages that reflects a more realistic level of productivity savings in the

disability sector. It proposed a wage cost index be used based on the

Australian Bureau of Statistics Wage Cost Index (ABS WCI) combined with a

general Consumer Price Indicator (CPI) inflator to cover costs not related to

wages. It noted that over recent years the ABS WCI had grown at twice the rate

of the Wage Cost 2, currently applied to Commonwealth CSTDA funding.[73]

The SPRC study also noted the need for indexation of CSTDA funding to address

on-costs for service providers such superannuation and workers compensation

insurance.

3.100

The Committee notes the annual September quarter 2006 ABS Wage Price Index

seasonally adjusted increase for all employee jobs in Australia was 3.8 per

cent.

Recommendation 8

3.101

That the Commonwealth set an indexation level in line with the actual

costs of delivering services. This rate should be applied as a minimum

indexation rate by State and Territory Governments.

Demand funding

3.102

A number of submissions argued that the current CSTDA lacks long-term

strategic planning for increasing demand for specialist disability services. In

general demand adjustments to funding seek to ensure that the relationship

between the supply of services and the demand for services remain the same. For

example to adjust funding to account for increases in the population or in

prevalence of disability in the population which would increase demand for

services.[74]

Ms Felicity Maddison of the National Carers Coalition commented:

...the whole CSTDA is crisis driven as to the rollout of support.

Because of the lack of the bulk of funding that is available, funding is

rationed and it is coming out—it is being rolled out—on the basis of crisis

intervention rather than in a well-constructed forward planning process. There

is no evidence of long-term planning for the future and you are getting a lot

of flavour-of-the-month-type initiatives coming through...[75]

3.103

In the current CSTDA demand adjustment and growth funding is dealt with

in Part 8 (8):

Commonwealth, States and Territories acknowledge demand management

requires regular annual growth in funding levels to continually improve the

level and quality of services and the efficiency of systems for specialist

disability services. The States/Territories will provide annual funding growth

at a level agreed between each State/Territory and the Commonwealth over the

life of the Agreement for services they are directly responsible for

administering under the Agreement.

3.104

The CSTDA arrangements do not require multi-year budgetary planning

based on demand growth. Some submissions proposed population-based benchmark

funding similar to that used for the funding of aged care services would be

more appropriate for funding calculations for disability services.[76]

ACROD commented:

Aged Care uses a needs-based planning framework that seeks to

achieve and maintain a national provision level of 108 residential places and

Community Aged Care Packages (CACPs) for every 1,000 of the population aged 70

years and over. While there is some debate about the formula, its aim is to

ensure that the growth in the number of aged care places is in line with growth

in the aged population and that there is a balance of services, including

services for people in rural and remote areas.

The disability sector has nothing similar to guide the provision

of residential and community care places to people with disability. We know

that only 48 of every thousand persons in the comparable population (broadly,

people under 65 years with a severe or profound core activity restriction)

receive a CSTDA-funded disability accommodation support service.[77]

3.105

The Committee notes that the Disability Policy and Research Working

Group (formerly the National Disability Administrators) is conducting research

into Demand Management due for completion in June 2007.

Recommendation 9

3.106

That the next CSTDA incorporate appropriate benchmarks and annual

targets in relation to identified unmet need for specialist disability

services.

Growth Funding

3.107

Several State and Territory submissions noted that their CSTDA funding

contributions for specialist disability services were growing at a faster rate

than those from the Commonwealth. The Queensland Government noted that:

The Queensland Government has made significant additional

investments in disability services in recent years representing a commitment at

the State level to respond to needs of people with a disability. A

commensurable effort by the Commonwealth Government has not been realised.[78]

3.108

However, a larger proportion of new Commonwealth funding has gone into

the disability employment services which it directly administers. Over the

course of the current agreement annual Commonwealth funding of disability employment

services has increased from $303 million to $486 million while funding to the

States and Territories for special disability services has increased form $521

million to $616 million.[79]

3.109

ACROD suggested the following reasons for this trend:

This reflects the Commonwealth's view that:

- implementing

the ambitious raft of disability employment service reforms required additional

spending on those services;

- States are

insufficiently accountable for the expenditure of funds they receive from the

Commonwealth;

- State-administered

services are principally the responsibility of the States; and

- higher-than-expected

GST revenue should reduce the States' call on Commonwealth specific-purpose

transfers.[80]

3.110

The State and Territory Governments also expressed concern that increases

in the level of CSTDA funding were not being reflected in requirements set in

the Bilateral Agreements.

The Australian Government applies a "matched funding"

requirement as a part of most bilateral agreements, but there is no structure

in place to acknowledge additional funding efforts made by the States and Territories.

A further shortcoming of the Commonwealth’s introduction (as

part of a regime of input controls) of a ‘matched commitment’ at the time of

signing an agreement is that this does not recognise previous efforts of States

and Territories. This can create a disincentive to states in making additional

efforts in growth funding during an agreement as this additional effort becomes

effectively locked-in to areas that may not be reflective of need in the State

or Territory.[81]

Recommendation 10

3.111

That the next CSTDA ensure 'matched funding' commitments do not provide

a disincentive for governments to provide additional funding for specialist

disability services.

Equity of funding distribution

3.112

A number of State and Territory Governments argued the Commonwealth

funding for specialist disability services was not distributed equally amongst

the jurisdictions in relation to their proportion of people with disabilities.[82]

For example the Victorian Government commented:

Victoria receives less than its equitable share of Commonwealth funding,

which results in an estimated shortfall of some $40 million over the life of

the current CSTDA.[83]

3.113

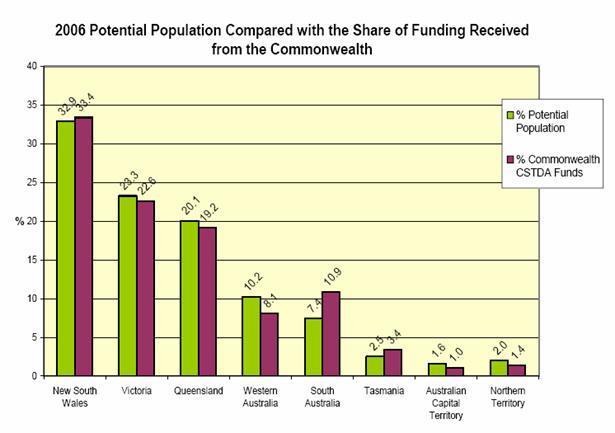

The Western Australian Government provided a graph, reproduced as Table 3.3,

to illustrate what it suggested was a lack of equity in the distribution of

Commonwealth CSTDA funding in relation to potential population.[84]

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) estimates 'potential

population' in each jurisdiction to broadly indicate the number of people with

the potential to require specialist disability services at some time. The potential

population for each jurisdiction is calculated from population disability

survey estimates and is constructed for comparative purposes and to provide indications

of relative need.[85]

Table 3.3:

Funding equity in relation to potential population

Source: Western Australian Government, Submission 3a,

p.23.

3.114

The current distribution of Commonwealth funding is based on historical

arrangements present during the first CSDA. During the negotiations for the

current CSTDA parties considered solutions for a more equitable distribution of

Commonwealth funding. The Western Australian Government commented:

...Ministers considered options for an accelerated equity formula.

The Commonwealth Minister took the position that they would allocate their

growth funds on whatever equity funding formula agreed to by States/Territories.

Ultimately, agreement was not reached, and the overall distribution of funding

to the States and Territories has remained inequitable. The Commonwealth was

not prepared to provide additional funding to address the equity issue.[86]

3.115

The Northern Territory Government also identified funding equity issues

in relation to other factors, such as the costs of service delivery:

29% of the Northern Territory population are

Aboriginal...Australian Institute of Health of Welfare (AIHW) estimates indicate

the Aboriginal people are 2.4 times as likely to have a severe or profound

disability as non-Indigenous Australians...The Northern Territory also has the