Chapter 3 - Incomes

3.1

The Commonwealth Government assists in enhancing the living standards

and ameliorating the cost pressures faced by retirees through the retirement

income system, as well as supporting the provision of subsidies and

concessions. The retirement income system is primarily comprised of what are

considered to be three pillars: the public funded age pension, compulsory

superannuation through the Superannuation Guarantee, and voluntary

superannuation contributions and private savings.[1]

Older people can also be on a variety of other pensions including the

disability support pension, veteran's pension and carer payments.[2]

3.2

The inquiry highlighted to the committee the increasing importance of other

measures outside the three pillars for assisting older people in meeting the

costs of living. These include the taxation system, taper rates and concessions

in assisting the capacity of older people to cope with the cost of living. In

particular, the Commonwealth Government provides substantial funding for subsidies

and concessions, including health services and pharmaceutical discounts, aged

care and rental housing, which contribute to reducing expenses for older people

and increasing their disposable incomes.

Superannuation savings

3.3

Superannuation is the key vehicle of the retirement income system and

allows older people to maintain a higher standard of living than offered by the

pension system alone. It involves compulsory savings through employment with

contributions by employers on behalf of employees. Although many, and an

increasing number of retirees, have some superannuation to supplement a part

pension, the majority of retirees have limited benefits from compulsory

superannuation. According to FACSIA, superannuation assets constitute 6.6 per

cent of the wealth of older households. This is the result of the conversion of

superannuation lump sums into other assets and the restricted capacity of

current retirees to accumulate savings, due to the limited access to the

superannuation system over the course of their working lives.[3]

3.4

According to research by NATSEM, half of 50-64 year old Australians have

very little wealth with which to support their retirements. The financial situation

for early retirees is bleak according to this research. In 2004, half of retirees

aged 55-59 had incomes of less than $10 000 per year and very little

superannuation, forty per cent had no superannuation and 25 per cent had less

than $25 000.[4]

In 2004, almost half of retired couples had a combined income of less than

$20 000 per year. The incomes of many retirees generally rises as they

reach preservation age and gain access to superannuation, but then falls within

about five years, possibly as their superannuation is exhausted.[5]

Only one quarter of retirees aged 55-59 had more than $100 000 in

accumulated superannuation, according to 2005 research.[6]

3.5

There are various reasons for the inadequate levels of superannuation

among much of the retired Australian populace. Most importantly, compulsory

superannuation was not introduced until 1992. FACSIA submitted that prior to

the introduction of award superannuation in 1986, approximately 39 per cent of

the working population received superannuation contributions. Compulsory

superannuation now extends to 95 per cent of full-time employees and 78 per

cent of part time employees.[7]

The rate of superannuation guarantee contributions was lifted to nine per cent

of wages on 1 July 2002.

3.6

However, for many retirees, and those of or approaching retirement age,

these reforms were insufficient and introduced too late to make a substantial

difference to their retirement incomes. Numerous submissions to the inquiry

highlighted that current retirees worked during a very different policy

environment and had limited opportunities to generate superannuation to enhance

their quality of life in retirement.[8]

These retirees left the labour market before compulsory superannuation was

introduced and/or had sufficient time to produce tangible benefits. The level

of compulsory contribution was designed to provide an income stream of

approximately 40 per cent of final salary on retirement after 40 years

full-time employment. Current retirees did not contribute to their retirements

for this period. Future retirees also potentially face similar problems if out

of the full-time employment market for extended periods. This can be the result

of contract and casual employment, caring responsibilities or long periods of

absence due to education.[9]

The importance of employment

patterns

3.7

Research has shown that women in retirement or of retirement age have

been particularly disadvantaged on average, with less than half the

superannuation balances of men.[10]

FACSIA's submission to the inquiry also noted that single women in both

retirement and pre-retirement cohorts have lower average and median

superannuation balances than single men.[11]

Catholic Social Services Australia submitted that almost 90 per cent of women

aged 60-64 in 2003-04 had balances of under $100 000 and 75 per cent had

less than $40 000—considered to be a low level.[12]

3.8

Women are more likely to have accumulated lower retirement savings than

men, due to their employment patterns. These include greater career

interruptions as a result of family responsibilities, lower gender-based pay

rates, lower average wages, greater concentration in casual and low paid

employment and, prior to the introduction of compulsory superannuation, greater

likelihood of employment in industries or occupations where employers did not

contribute to superannuation. These findings were provided in a report by the

Commonwealth Government in conjunction with the University of Melbourne and the

Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research. The report

highlighted:

Women, particularly women living alone, currently have very

limited capacity to provide for themselves financially in retirement and are

more prone to live in poverty or on a low income in retirement.[13]

3.9

Evidence provided to the inquiry in submissions also argued that women had

often historically been compelled to resign from employment when they married

or became pregnant.[14]

3.10

The Aids Council of NSW (ACON) argued that sufferers of chronic

illnesses, such as HIV/AIDS, also experience interruptions related to their

employment, which impacts on their financial status in retirement.[15]

3.11

The financial difficulties in preparing for retirement as a result of

chronic illness were illustrated by Mr Bede Haywood who submitted:

Getting hereditary cancer at the age of 30 yrs impacted on my

whole life. It put an end to securing Bank and house loans, I was not allowed

to increase my superannuation, personal insurance was a no go area and getting

another job just about impossible particularly if it required a medical. So

saving for retirement was not an option and being forced to leave the workforce

early did not help.[16]

3.12

Only 29 per cent of people aged 45 and above who have not yet retired,

believe they will need to rely on government benefits.[17]

However, there is a discrepancy between expectations about life-style and

vehicles for funding retirement, and the reality. Although many of those in

retirement and those about to retire have only limited superannuation savings,

the National Institute of Accountants argued that workers almost consistently

underestimate their financial needs in retirement and many underestimate their

life expectancy.[18]

Along with this, some lack the necessary financial and investment skills to

adequately prepare for their retirement.

Pension provisions

3.13

The age pension provides a safety net for older people with limited

retirement savings and increasingly has a role as an income supplement. It is

means-tested and designed to support a modest standard of living and

ensure recipients can afford basic level participation in society. As at 1 July 2007, the full pension rate was $13 652.60 per year for singles and

$22 802 for a couple.[19]

This equates to $262.55 per week and $438.50 per week for single and couple

pensioner households respectively.

3.14

Government benefits—primarily the age pension or veterans'

payments—remain the principal source of income for three-quarters of

Australians aged 65 and above. Only 10 per cent rely primarily on

superannuation.[20] The Hobsons

Bay City Council submitted that 80 per cent of its residents aged 65 and above are

reliant on the age pension.[21]

3.15

FACSIA submitted that the means-testing of eligibility for the age

pension encourages regular consumption of capital over the course of

retirement. It maintained that even modest savings can have a substantial

effect on retirement income of age pensioners if consumed regularly, enhancing

total income by 15 per cent for singles and 17 per cent for couples over the

age pension alone. FACSIA reported that its economic modelling suggests part

pensioners experience even greater benefits. This includes a 49 per cent

increase over the pension entitlement for singles and 67 per cent increase for

couples.[22]

3.16

The Department of Veterans' Affairs (DVA) pays pensions on the basis of

age or invalidity to eligible veterans and partners, widows and widowers, as

well as income support supplement for war widows and widowers with limited

means and an income support allowance for eligible recipients of the disability

pension. The DVA age service pensions are paid according to the same income and

assets test as recipients of the age pension, but are paid five years earlier

than the social security age pension. This reflects the effects of war service

and impact on ageing and earning power. The invalidity pension may be paid at

any age before a person turns 65 and is not means tested. Service pensions also

have eligibility for pharmaceutical allowance, rent assistance, telephone

allowance, utilities allowance and remote area allowance.[23]

The increase in partial-pension

recipients

3.17

While the number of retirees receiving pensions has increased, this is

due to a gradual increase in the proportion of older people receiving partial

pensions. At the same time, there has been a decrease in the proportion

receiving the full pension. Those receiving a part pension have their incomes

supplemented by superannuation and generally receive a higher level of income

than those receiving the full pension.[24]

3.18

Over the past 10 years, the Australian Government has altered the

pension taper rates to ensure part-rate pension recipients receive greater

pension payments for a given level of private assets or income. Along with this

is a higher cut-out point. Consequently, a greater proportion of pensioners

have become eligible for part pensions.[25]

3.19

In July 2000 the income test taper rate was reduced from 50 cents to 40

cents in the dollar to compensate for the introduction of the new tax system.

This has increased the disposable income of part-rate income tested pensioners

and increased the number of people eligible to receive pension payments. For a

person with a $20 000 annual wage, the changed taper rates yield a benefit

of $1 540 per year.[26]

3.20

Under the Better Super reforms, from 20 September 2007, the taper rate will ensure the pension is withdrawn more slowly and the point at which the

pension cuts out is much higher. The pension assets test taper rate will be

halved, so that pensioners only lose $1.50, rather than $3, for each $1000 over

the asset test threshold. The changes will also make some that were previously

ineligible for any pension to qualify for a part-pension. FACSIA submitted that

the changes have been designed to increase incentives for saving for retirement

and increase workforce participation by reducing the effective marginal tax

rate. It also increases the disposable income with a person with investments

yielding a $20 000 income benefiting by $3 831 per year.[27]

3.21

The value of assets held without losing pension eligibility has

increased. FACSIA submitted that single pensioners that own their own home have

had assessable assets increased from $343 750 to $520 750, and couples

from $531 000 to $825 500. Similarly, single pensioners that do not

own their own home will have their asset threshold raised from $464 750 to

$641 750 and couples from $652 000 to $946 500.[28]

Indexation of retirement benefits

Pension indexation

3.22

The age pension is means tested and indexed twice each year (in March

and September) to protect its value against inflationary increases in prices

and rises in wages growth. In particular, the pension is indexed according to

the higher rate of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or 25 per cent of male total

average weekly earnings (MTAWE). The addition of the indexation to reflect

values in MTAWE commenced in 1998, as a result of legislation introduced in the

previous year.

Effect of indexation linked to

earnings

3.23

From 1982 to 1997-98, the real average incomes of older people rose as a

proportion of average incomes for the population as a whole, according to

research by FACSIA. This included a rise of 5.7 per cent for older couples and

6.7 per cent for older singles, compared to a real increase of four per cent

for the broader population.[29]

3.24

FACSIA provided evidence that the indexation of the pension to at least

25 per cent of MTAWE has ensured that the real value of the pension has

increased above the CPI and the age pension cost of living index. That is, the

pension rate has increased by 48 per cent, compared to a rise of 30.2 per cent

for the CPI and 32 per cent for the pension cost of living index. This

increased the payments to single pensioners by $72.80 per fortnight and to

couples by $122.60 per fortnight.[30]

3.25

The indexation arrangements have coincided with high growth in the

economy. Over the past five years, this has translated into wages growth

outstripping the CPI and, consequently, a rise in the real value of the pension,

due to the pension indexation arrangements. This coincided with a reduction in

the proportion of older people for whom government benefits were the principal

source of income—from 74.7 per cent to 65.4 per cent for couples and from 82.1

per cent to 79.7 per cent for singles—and a rise in the significance of other

forms of income.[31]

3.26

Pension increases have exceeded CPI increases on 11 of the 16

indexations between 1997 and the time of the inquiry. On the other five

indexations (20 March 2000, 20 March 2001, 20 September 2004, 20 March 2005 and 20 September 2006), the pension increased in line with the CPI, which

increased at a greater rate than MTAWE. FACSIA has estimated that the

indexation of the pension to MTAWE has increased age pension expenditure by $12.99

billion (in December 2006 dollars) than it otherwise would have been.[32]

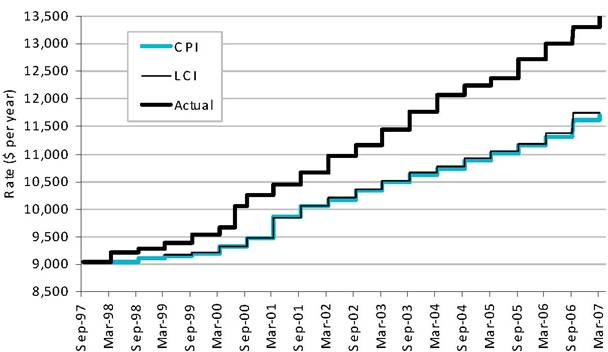

Figure 3.1 highlights the growth in the real value of the pension compared to

rises in the CPI.

3.27

In addition to FACSIA, other evidence to the inquiry strongly supported

the benefits of indexation of the age pension to MTAWE. The Brotherhood of St

Laurence told the committee:

With the introduction of MTAWE, many of the concerns of our

organisation in relation to the financial wellbeing of older people were

essentially being addressed by government policy directions.[33]

3.28

Despite this evidence, the committee received numerous anecdotal

submissions that the pension is not maintaining its real value in the face of

increasing cost of living pressures. The Combined Pensioners and Superannuants

Association acknowledged the rise in the real value of the pension. However,

the association argued that full rate pensioners still experienced financial

stress.[34]

Both Catholic Social Services Australia and Ms Beth Butler maintained that this

was because the indexation level of MTAWE of 25 per cent was simply

insufficient to provide an adequate standard of living for age pensioners.[35]

Figure 3.1: Actual pension rates – increases compared to

increases in line with CPI only, and ABS analytical living cost index for age

pensions only

Source: Submission 138, p.19 (FaCSIA).

3.29

According to evidence provided by the NIA, the increase in the real

value of the pension following its indexation to MTAWE contrasts with the norm

in various other OECD countries where the level of pension allocations are

being reduced as a means of encouraging better retirement planning.[36]

Similarly, Australia Fair research notes that Australia has relatively good

minimum wages compared to other OECD countries,[37]

which emphasises the value to pensioners of indexation to wage growth.

3.30

Also, despite the evidence of the real growth in the value of the age

pension over the past year, some submissions raised concerns about the

longevity of this result. Concerns were expressed about any decline or suppression

of wage levels and the use of non-wage remuneration to accommodate increases in

the costs of living, such as tax cuts, for workers. In particular, the Defence

Force Welfare Association (DFWA) highlighted that MTAWE excluded superannuation

contributions, fringe benefits and work-life trade offs. DFWA used the example

of the introduction of the Superannuation Guarantee Charge in the early 1990s,

which resulted in a slowing of wage rises, although workers received monetary

remuneration with rises in their superannuation balances.[38]

Various submissions highlighted that those in the labour force had been

compensated for cost of living pressures through adjustment of taxation scales.[39]

However, these benefits did not accrue to pensioners because they did not pay

tax, despite being faced with many of the same cost of living pressures.

3.31

Similarly, some submissions to the inquiry raised concerns about the

impact on the indexation and retirees' lifestyles as a result of the Coalition Government's

Workplace Relations reforms allegedly suppressing wages growth.[40]

The Australian Pensioners' and Superannuants' League Queensland (APSL QLD)

highlighted information allegedly leaked from the Government, which suggested

that many workers experienced the elimination or reduction of additional

payments from workers' earnings and did not receive pay rises over the life of

workplace agreements.[41]

The suitability of CPI indexation

3.32

The potential for future economic downturns and declines in wages growth

brings to the fore the importance and validity of the other indexation measure

for age pensions—the CPI. However, concerns were expressed in a large number of

submissions about the suitability of the CPI for measuring the cost of living

rises for older people.

3.33

FACSIA acknowledged that pensioner households have comparatively higher

expenditure on food, health and housing, and less on transportation, education

and financial and insurance services than other households. Self-funded

retirees have comparatively higher expenditure on household contents,

recreation and health, and lower expenditure on education, financial and

insurance services. However, FACSIA argued that the cost of living indexes for

pensioners and self-funded retirees were only marginally above the CPI for the

year between the June quarters in 2005 and 2006. FACSIA argued that quarterly

changes in certain commodities influenced community perceptions of the effect

of cost pressures on the living standards of older persons.

3.34

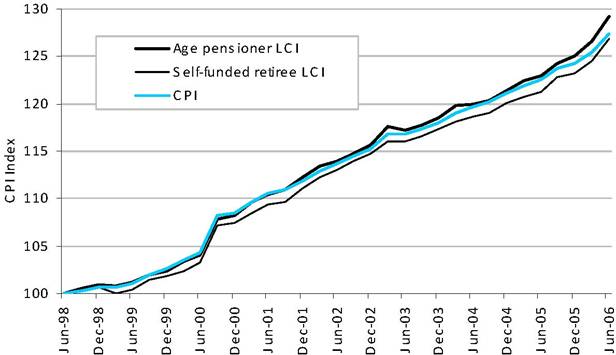

Both FACSIA and the ABS have noted that the differences between the cost

of living indexes and the CPI between June 1998 and June 2006 were moderate

(see figure 3.2). The pensioner living cost index average was 3.3 per cent, the

self-funded retiree index average was 3.0 per cent and the CPI average was 3.1

per cent. This resulted in overall rises of 29.2 per cent, 26.9 per cent and

27.4 per cent respectively.[42]

Figure 3.2: Comparison of Index Numbers for living cost

index of age pensioner households, self-funded retiree households and CPI

Source: Submission 138, p.19 (FaCSIA).

3.35

Nevertheless, numerous submissions expressed concerns about the accuracy

of the CPI as a reflection of inflation experienced by pensioners and retirees

and the consequential erosion of the value of their incomes.[43]

3.36

The St Vincent de Paul Society argued that the standard CPI data is of

'limited use' in understanding the impacts of price changes on different

sectors or sub-groups of the community. CPI is a measure of broad economic or

inflationary trends, with the 'CPI basket' representing the average expenditure

of all private households in the eight capital cities. It does not, however,

recognise household sub-groups and therefore cannot assess the differing

impacts of price changes on household sub-groups.[44]

The St Vincent de Paul Society argued that as a result of 'the anomaly between

average and actual households', government transfers that are indexed to the

CPI give rise to either 'over generous payments' or 'payments which

underestimate the actual cost of living'.[45]

3.37

The St Vincent de Paul Society pointed out that household consumption

patterns are influenced by stages in the life cycle and various life styles. It

was argued that different consumption patterns affect the cost of living of

different households. The relevance of the CPI – that is, how well an

individual household's cost of living 'correlates with the official CPI' –

depends on how closely the household consumption pattern reflects the CPI

consumption pattern.[46]

3.38

More specifically, Dr Paul Henman observed that the CPI may not accurately

reflect the spending patterns of older people:

[T]he ABS's CPI basket of goods and services is chosen to be

representative of Australian households as a whole, and as such, may not

reflect the basket of goods and services that older Australians are likely to

purchase.[47]

3.39

By way of example, Dr Henman went on to note that older Australians

might be more likely to spend less on housing costs and more on health

services.[48]

Similarly, other witnesses pointed to basic essential costs, such as food, petrol

and fares, electricity, medical fees and pharmaceutical prices, as being of

greater importance in the costs of living for retirees.[49]

3.40

COTA argued that people on low and fixed incomes, such as age pensioners,

exhibit expenditure patterns that are markedly distinguishable from those of

the average person. It was noted that the ABS reported that between 1998 and

2006 the living costs for age pensioners showed the greatest increase of any

household type.[50]

COTA argued:

We estimate that for some groups of pensioners costs may have

increased by 15 points more than is reflected in the CPI over a 15 year period.

Indigenous older people and those from culturally and linguistically diverse

backgrounds are over-represented amongst these groups.[51]

3.41

COTA and the Ethnic Communities Council of Victoria cited similar

research from St Vincent de Paul to highlight the changes in the CPI compared

to costs more directly relevant to older persons. Weightings emerging from this

study indicated that from 1990 to 2005 the CPI rose to 148.8 while the cost of

living for age and disability pensioners (who were home owners and used private

transport) increased to 153.99. For those in rental accommodation, it rose to

162.93. This was due to large rises in transport costs, health costs, dental

services, insurance, utilities, dairy products and bread.[52]

The Ethnic Communities Council also argued:

This specialised research seems to match the anecdotal and very

vocal feedback we have received from our membership that their income levels

are declining and that they are suffering significant disadvantage and hardship

despite Australia’s generally high level of economic prosperity over the last

15 years.[53]

3.42

However, FACSIA expressed reservations about the methodology

underpinning the cited St Vincent de Paul research at a public hearing in Canberra[54]

and expanded on these concerns in a supplementary submission to the inquiry.

Based on the St Vincent de Paul's published material - Winners and Losers

– the newly named FaHCSIA (Department of Families, Housing, Community Services

and Indigenous Affairs) identified several factors that, it believes:

limits the usefulness and applicability of the Society's RPI

modelling', and leads to questions about the Society's claim that some groups

face increases in their cost of living of 30 per cent above the CPI.[55]

3.43

The DFWA made the point that the CPI does not take account of changing

spending patterns, notably that: technological and economic progress often

means that items previously considered luxuries can become norms; cost

pressures often result in the purchase of qualitatively inferior products; and

market changes can require additional spending, such as reductions in public

transport services requiring greater reliance on private transport.[56]

3.44

Similarly, Dr Henman argued that consumption is not a static thing:

There is a number of factors which mean that the basket of goods

and services Australian households consume change over time'. These factors

include 'growing living standards', 'technological change' and 'changing social

dynamics.[57]

3.45

Dr Henman noted that, in particular, certain price pressures have not

been adequately captured in the CPI basket. These price pressures include

banking fees and charges; mobile phone services; internet access; and the

reduction in bulk billing by GPs.

3.46

The ABS confirmed the limits of the CPI as a measure of the cost of

living and argued that the analytical cost of living indexes are more

appropriate mechanisms. The analytical cost of living indexes, including the

ABS Pensioner Price Index, draw on information from the Household Expenditure

Survey and have been designed to determine the necessary rise in income to

allow continued purchases of the same quantity of consumer goods and services.

The analytical cost indexes consider the impact of price changes on a

particular household demographic (rather than a community average), use the

national expenditure patterns for this group (rather than just in capital

cities), and accommodate items such as house purchases and insurance in a way to

better reflect a cost of living index:

The indexes represent the conceptually preferred measures for

assessing the impact of changes in prices on the disposable incomes of

households...The Australian CPI, on the other hand, is designed to measure price

inflation for the household sector as a whole, and as such, is not the

conceptually ideal measure for assessing the impact of price changes on the

disposable income of households.[58]

3.47

The CPSA submitted that the ABS Pensioner Price Index was a more

suitable measure of inflation experienced by pensioners than the CPI. CPSA

highlighted that from 2001-2002, the ABS Pensioner Price Index began increasing

at a rate higher than the CPI. However, the CPSA argued that the ABS Pensioner

Price Index still has deficiencies. The ABS Pensioner Price Index measures

actual expenditure – that is, it captures the spending behaviour of pensioners

rather than creating a 'normative' basket of goods and services that reflects

what 'experts' believe pensioners need.[59]

However, as the CPSA pointed out, the focus on actual expenditure does not take

into account the expenditure required but unaffordable to pensioners.[60]

Similarly, the Brotherhood of St Laurence and the Ethnic Communities Council

of Victoria raised concerns during the inquiry about the differences between

ABS data, including on the household indexes, and anecdotal reports that the

cost of goods and services are outstripping the CPI.[61]

The Brotherhood of St Laurence called for more detailed modelling of the

movement in the costs of goods and services.[62]

3.48

Along these lines, Dr Paul Henman stressed the difference in living

standards for older Australians who own their homes outright and those in the

private rental market, who 'face quite different and accelerating financial

pressures'. Accordingly, he suggested that the ABS develop a CPI index for

privately renting older Australians on the full-rate Age Pension.[63]

Further, Dr Henman noted that Australia does, in fact, already have 'high

quality research tools and datasets'[64]

to undertake up-to-date assessments of the cost of living pressures and the

impacts of these on older Australians, including sub-groups of older

Australians (homeowners, private renters and social housing renters for

example).[65]

Indexation of other retirement

benefits

3.49

Concerns about the indexation of retirement benefits were also raised in

relation to military pensions and commonwealth superannuation.[66]

The indexation of disability pensions was similarly raised, although there was

bi-partisan support during the 2007 election campaign to index these in line

with the age pension. It was argued that the acknowledgement of the utility of

MTAWE in ensuring the age pension maintains its real value by community living

standards, underscores the need for a similar mechanism for other retirement

benefits. Many of these benefits remain indexed solely according to rises in

the CPI and have had their comparative value eroded, if not their real value. In

particular, frustration was exhibited at the maintenance of Commonwealth

superannuation and some defence payments at their existing level on 5 July 2007, due to the CPI not increasing.[67]

3.50

DFWA noted that the difference between military pensions indexed at the

CPI rate and the MTAWE was 29 per cent since 1990 in the favour of MTAWE.[68]

Similarly, Mr Bert Hoebee argued that since June 1997, the age pension had

risen by 51 per cent, compared to military pensions by 30 per cent. He

submitted:

There is clear evidence of the annual decline in Defence

retirees' pensions' purchasing power and many of us therefore feel like

second-class Australians, facing a continuing decrease in our standard of

living as we grow older, despite years of loyal service to the nation.[69]

3.51

This was echoed by military retiree Mr Ray Gibson, who submitted that

over the last decade military pensions have fallen approximately twenty percent

behind rises in the age pension.[70]

3.52

The Superannuated Commonwealth Officers' Association argued that as Commonwealth

superannuants' superannuation incomes are indexed by the CPI they are unable to

keep pace with charges, such as some government fees, which are indexed at a

higher rate. For example, Motor Vehicle Registration fees in the ACT are

indexed according to MTAWE.[71]

3.53

The 2002 Report on Superannuation and Standards of Living in

Retirement by the Senate Select Committee on Superannuation recommended

that commonwealth superannuation be indexed in the same way as benefits such as

the age pension, to the higher of MTAWE or CPI. However, the Government's

response to the report stated that it considered the CPI to provide an

'equitable and satisfactory method over a period of years for increasing

pensions'. This was based on ABS data between June 1998 and June 2004,

indicating the CPI had increased by 19.7 per cent, compared to 18.6 per cent

for the cost of living index for self-funded retirees. The Government also

reported that altering the indexation arrangements would have a substantial

fiscal impact on the budget that would be difficult to sustain.[72]

3.54

Against the (former) Government's response noted above, Mr Coleman from

the Superannuated Commonwealth Officers Association told the committee that

there is 'ample evidence' that bringing superannuation indexation arrangements

in line with indexation arrangements for the Age Pension is 'fair, affordable

and long overdue'.[73]

The adequacy of income levels for older people

3.55

A key aspect of measuring the cost of living for older people is

ascertaining the adequacy of the incomes and their capacity to keep pace with

movements in the price of basic and essential goods and services. As has

already been established, older people form a very diverse demographic and

incomes can be wide-ranging.

3.56

The inquiry received numerous anecdotal submissions about older people

experiencing financial stress. However, most of the research data seems to

suggest that many older people have the means to provide a frugal but modest

standard of living. This was illustrated in the submission of the Brotherhood

of St Laurence. The submission pointed out that unlike younger singles and families

receiving income support, income received from the age pension was higher than

the poverty line. Couples who received the full pension and owned their own

home were $150 per week above the poverty line and singles who did not own

their own home were $29 per week better off.[74]

3.57

FACSIA submitted data and statistics on trends and the general

circumstances of older people. FACSIA pointed to ABS data that highlighted that

the average after-tax income of older households was $23 800 with the

median $20 020 in 2003-04. FACSIA submitted that the disposable income of

older persons was approximately half of that of all households, although this

was increased to two-thirds after factoring in lower responsibility for

dependents.[75]

3.58

Other research by FACSIA suggests that older people are less likely to

experience income poverty than younger people, although these findings are

dependent on the measure employed. On before-housing poverty measures,

poverty was found to be higher in the youngest cohort (18-24 year olds) and the

two oldest age cohorts (65-70 and 70 and older). Of those 18-25 years, 20 per

cent lived in poverty, while 30 per cent of those older than 70 lived in

poverty. This was compared to less than 4 per cent of those aged 25-54 living

in poverty. But the research found that age was negatively associated with

after-housing income poverty and financial stress, which reflects the

lower housing costs of older households.[76]

Measures of retirement income

adequacy

3.59

Most of the research about adequate retiree income levels calls for

either a level necessary to achieve a certain standard of living based on

meeting certain essential costs, or a level based on an arbitrary percentage or

replacement rate of pre-retirement income.

3.60

ASF highlighted that it considered the Australian pension scheme to be

'one of the best schemes in the world' and, unlike many other countries,

remained affordable. However, it raised the issue of the lack of investigation

into the adequacy of the pension. It provided the following evidence:

There has never really been a guide—a basket of goods and

services—that sets the age pension. It has been a little bit of guesswork. It

was the CPI increase and then it was average weekly earnings...There is nothing

magic about 25 per cent of average weekly earnings. When we talk about doing

something on the adequacy of the age pension, there needs to be a basket of

goods and services looked at so that we do have a base, which we do not now.[77]

3.61

Consequently, most research into the adequacy of retirement incomes focuses

on replacement rates. FACSIA submitted that a replacement rate less than 100

per cent is generally considered acceptable for retiree incomes because

retirees do not typically face the major expenses incurred by people of working

age. This includes mortgage repayments, education expenses, child care fees and

work-related costs. Further, older people also often have access to concessions

and other age related services. Replacement rates are anticipated to rise as a

result of the maturation of the superannuation system from over 60 per cent in

2006 to 80 per cent by 2016.[78]

3.62

It has been suggested that these replacement rates would potentially

provide older people with higher standards of living in retirement than

experienced during their working lives. In particular, working people generally

do not have access to these proportions of their income as disposable income.[79]

3.63

A level of 65 per cent of full-time pre-retirement income has often been

cited as necessary to achieve an adequate retirement life-style. However,

research by AMP and NATSEM has determined that most retirees rely primarily on

the age pension and have an income of less than half of this amount.[80]

This was echoed in evidence before the inquiry with most of the submissions from

age pensioners highlighting difficulties in meeting cost of living expenses considering

the provisions of the age pension. While the proportion of retirees reliant on

the full age pension is likely to decline over time as superannuation matures,

the current situation of some retirees remains of concern.

3.64

COTA argued that people 65 years and above have the lowest average

incomes in Australia.[81]

According to Queensland Shelter, Australians over the age of 65 are

concentrated at the bottom of the income spectrum and constitute 43 per cent of

low income households.[82]

The Brotherhood of St Laurence submitted that older Australians are more highly

represented in the lowest two income quintiles than in the higher quintiles.[83]

3.65

Some submissions suggested that the benchmark for the level of income

required should be the Westpac-ASFA Retirement Living Standard amount required

to ensure a modest standard of living in retirement. A modest income involved a

basic standard of living that excluded eating out, travel, private health

insurance, running a motor vehicle or entertaining at home. Some submissions

raised concerns at the discrepancy in the Westpac levels and those of the

maximum age pension.[84]

ASF noted that the shortfall was 13 per cent for pensioner couples and 35 per

cent for single pensioners per year.[85]

3.66

The Combined Pensioners and Superannuants Association has developed its

own definition of low retirement income thresholds. This includes the levels of

$18 500 per annum for single retirees and $25 500 for couples, which

are similar to the Westpac levels. The current full rate pensions fall below

these thresholds—the rate for singles is $13 652 per annum and couples is

$22 802. Pensioners in receipt of the full rate of pension are entitled to

earn some additional income—$3 432 for singles and for couples $6 032

per annum. The Combined Pensioners and Superannuants Association submitted that

the allowable additional income puts the couple pensioner earnings over the low

income threshold, but not singles. It was argued that 70 000 single full

rate pensioners have no additional income and that 600 000 have some,

though not necessarily the maximum, additional income.[86]

International comparisons of

pension systems

3.67

Similarly, Catholic Social Services Australia argued that public

spending on age pensions is low compared to most other OECD countries.[87]

The Australian Manufacturing Workers' Union (AMWU) asserted that poverty rates

among older persons in Australia were among the highest in the developed world

and social security replacement rates were at the lower end of the OECD

rankings.[88]

Other research of international comparisons undertaken by Australia Fair has

shown the financial situation of older Australians compares poorly with older

people in other OECD countries. This research highlights that the proportion of

older people living in low income households is above the OECD average. Almost

25 per cent of older Australians were deemed by the report to be living in

poverty (on less than 50 per cent of median income).[89]

The report stated:

In OECD nations, people in retirement and aged 65 and over

generally have lower relative income compared to those under 65. However, Australia

stands out as having the lowest relative income of older people in the OECD and

in 2000 Australia had the 6th highest poverty rate for older people in the

OECD. Major reasons for this are that our age pensions are set at a low flat

rate ($263 per week for a single pensioner in June 2007) while many other OECD

countries pay a proportion of their previous wage, and superannuation in Australia

has only become available to a majority of workers in the last decade or so.[90]

3.68

However, FACSIA noted that the Australian pension scheme is distinct

from the retirement income system in most OECD countries because the system is

funded by general taxation revenue rather than individual contributions made

throughout the working lives of recipients.[91]

According to the Productivity Commission, Australia is better prepared to deal

with the budget impacts of an ageing population on pension spending.[92]

Further, NIA explained that the OECD trends are changing. In particular – as

noted earlier - NIA provided evidence that in other OECD states, pensions are

being reduced and eligibility is being tightened. This includes a renewed focus

on supporting the lower paid workers, less generous pension indexation, pension

ages being raised to 65, the introduction of defined contribution pensions

where the private pension benefit depends on contributions and investment

returns, as well as other measures being introduced to preserve the

sustainability of the systems.[93]

The second world of retirement

3.69

The age pension is only designed to provide sufficient income for a

frugal standard of living, so finances for pensioners will always be tight.

However, anecdotal accounts and some of the evidence submitted to the inquiry

highlight that there is a minority of older people experiencing severe

financial stress. For instance, according to the Council of Social Service of

New South Wales, 13.9 per cent of the retired New South Wales population cannot

raise $2 000 for an important requirement, compared to 7.9 per cent of

full time workers.[94]

3.70

Dr Paul Henman made the point that many retirees must live on a limited,

relatively-fixed income for an extended period of time. During this time,

household durables such as cars and whitegoods wear out and need to be replaced.

For those with limited or no savings (and no capacity to save) these additional

costs are a significant financial burden. To this end, Dr Henman recommended

that a 'Pension savings account' be established, which would operate in a

similar way to the Savings Account in the Newstart allowance. That is,

Government would pay a notional ten dollars per week for each Age Pensioner,

which would accrue and could be withdrawn as needed to meet large, one-off

costs.[95]

3.71

ACOSS argued that the incomes of the top 20 per cent of retirees have

risen substantially over the past two decades, creating a gap in the living

standards of those with investment assets and other retirees.[96]

NATSEM research reached similar conclusions:

This raised the prospect of the 'two worlds of retirement'...there

will be one group of retirees who will be holidaying in camper vans and eating

out at restaurants—and a larger group who will be living for some decades on

the age pension with only limited personal resources to boost their living

standards.[97]

3.72

In its submission, the Brotherhood of St Laurence highlighted research

that suggests on average the incomes of older people grew slightly more than

for younger people from 1986-1997. However, this growth in incomes was not

evenly distributed. The income share of the upper quartile of older Australians

increased, while the share of the bottom quartile decreased.[98]

Further, the Brotherhood of St Laurence argued that the trend in increased

income for older people has not continued. It maintained:

In the 1990s, we grew increasingly confident that disadvantage

amongst older people was declining...However, experience this decade is

suggesting that the level of pensions and benefits is not keeping pace with

costs of living.[99]

The plight of the single pensioner

3.73

As has previously been outlined in this chapter, rates of pension,

allowances and income and assets test thresholds are determined by whether a

person is a single or part of a couple. The maximum single rate of the pension

is around 60 per cent of the maximum combined rate than can be paid to a

couple. FACSIA argued that the Australian rate is similar to overseas

standards, which average 60-70 per cent. This includes rates of approximately

56 per cent in Germany, France and Sweden to 66 or 67 per cent in the UK, New

Zealand and the US.[100]

3.74

But the evidence considered by the inquiry and discussed in this chapter

underlines that international comparisons for the pension system can be misleading,

including the relationship between the single and couple pension rates. As has

already been established in this chapter, the Australian pension system is

funded through different means and performs a different function than in other

OECD countries. Consequently, Australian public spending on pensions, their

replacement rates and the relative incomes of older people tend to be lower.

Therefore, the committee retains concerns about the appropriateness of the

level of the single pension and the appropriateness of its proportion of couple

entitlements.

3.75

These concerns were shared by several submissions and witnesses to the

inquiry - particularly with respect to the relative pension rates, allowances

and additional earning thresholds, and the capacity of single pensioners to

afford the costs of living.[101]

It was argued that the support provided to single pensioners is inadequate leaving

them either living in poverty or at extreme risk of falling into poverty. These

submissions asserted that income differences between singles and couples did

not reflect the benefit from cost sharing by couples. A number of costs that

changed little whether incurred by single or couple households were outlined including:

car registration and maintenance; petrol; insurance; gas; electricity; water;

telephone costs; council rates; body corporate fees; rent; house maintenance; home

appliances and furniture. COTA called

for the rate of the single pension to be lifted to 70 per cent of the couple

income, based on advice from the retirement income industry.[102]

Dr Paul Henman told the committee that research indicates that single retiree

home owners require 64 to 76 per cent of the couple pension to maintain a

reasonable standard of living, while private renters need even more. He noted that

the seven per cent difference between the Australian rate of 60 per cent and

the OECD modified equivalence scale rate of 67 per cent is significant.[103]

According to evidence presented to the inquiry, single households constitute 44

per cent of older households.[104]

3.76

The Australian Family Association argued that research by the Australian

Government Office for Women shows that the majority of retirees feel

financially secure and are able to adjust to receiving the lower income that

comes with retirement, except for single retirees.[105]

This was also reflected to a certain extent in the FACSIA submission, which

provided data on self-reported levels of prosperity. The demographics most

likely to describe themselves as poor or very poor were singles under the age

of 65, single parents, and single men and women aged 65-74.[106]

3.77

Some of the submissions used quantitative data and statistics to

highlight the precarious financial position of single pensioners. COTA noted

that key characteristics of the lowest income quintile groups are a greater

proportion of single households and greater reliance on government pensions and

allowances as the key source of income, such as the age pension.[107]

Similarly, the Combined Pensioners and Superannuants Association argued that on

its measure of low retirement income thresholds, single rate pensioners fall

well below these levels even if earning the maximum allowed additional income.[108]

The Women's Action Alliance (WAA) highlighted that single pensioners fall below

the Henderson Poverty Line (produced by the Melbourne Institute of Applied

Economic and Social Research at the University of Melbourne) for March 2007 of

$285.55 per week with an income of $265.45.[109]

These accounts were reflected in anecdotal evidence provided to the inquiry.

For example, Ms Janet Boddy relayed her problems in managing the costs of

living:

Those who are single incapacitated without family and living on

in their own homes on an age pension are acutely vulnerable. And I am one of

those people. At times I didn't know how I was going to have enough for food

let alone anything else I might require such as wood for the fire, clothing

etc.[110]

Single women

3.78

Evidence highlighted that single pensioners dependent on government

benefits were most likely to be single women.[111]

A report by the Commonwealth Government in conjunction with the University of Melbourne

and the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research submitted:

There is a pattern emerging in all the three themes – retirement

transitions, aspects of life in retirement and financial circumstances in

retirement – that single women appear to be facing disadvantage...Single women

had lower disposable incomes and lower superannuation balances and rely most

heavily on government pensions in retirement.[112]

3.79

Some of the submissions sought to explain the greater representation of

single women in disadvantaged financial positions. They argued that the

precarious financial position of single women was the result of government

policy, corporate norms and social pressures prevailing at the time, rather

than a choice not to prepare for retirement. Miss P A Robb submitted:

Women, particularly unmarried women, in my day were forced into

low-paying jobs at 60% of the male rate of pay...Banks until recent times would

not allow a single woman to borrow for a house. Married women were forced out

of the work force when two million men from the armed services were demobilised

after World War II, and jobs had to be found for them.[113]

3.80

Similarly, reflecting on the former circumstances of older people aged

sixty-three and over and on the full age pension Ms Jeanette Lindsay wrote:

Women in particular were deliberately excluded from

superannuation, called "temporary", and denied fair promotion or

equal pay with male peers. In the 1960s and beyond this occurred even when

these women were likely to be breadwinners with children...Male divorcees took

their superannuation with them, and very often did not pay support for their

children of a previous marriage.[114]

3.81

Government research has shown that as a result of these greater

financial pressures, retired single women are more likely than retired single

men or retired couples to sell their home and move to lower cost accommodation.[115]

Pensioners that suffer the loss of

a partner

3.82

The inquiry also received evidence about the impact of the death or

displacement to care of a partner on the financial stress of the remaining

partner. In many cases the remaining partners were women. FACSIA highlighted

the availability of the Bereavement Payment, which applies to surviving

partners for a period of 14 weeks following the death of a partner. Each year

24 000 age pensioners receive the payment, which amounts to approximately $1 927

per pensioner and $46.3 million for the government. It is designed to help fund

funeral expenses and smooth the transition from the couple rate to the single

rate of the pension, particularly to cope with the cost of bills incurred by

the deceased partner but not received until after the death.[116]

3.83

However, most of the submissions that addressed the impact of the loss

of a partner argued that the difficulty in surviving on a single pension is

particularly pronounced.[117]

The remaining partner is required to meet similar costs from a much reduced

income, as well as coping with death, or serious illness or health

deterioration that accompanied entry into care of a partner. The Combined

Pensioners and Superannuants Association described the loss of a partner as

'the pension trap'. The Association argued that there are 600 000 single

full rate pensioners in this situation, largely widows in their 70s and 80s.[118]

Mrs Zoe Ray recounted her difficulties in managing the cost of living

pressures after the death of her husband. She submitted:

When my husband died, my age pension was virtually cut in half,

as was my earning capacity and the amount of investments I was allowed to have.

I would like to point out that it is almost as cheap for two people to live as

one. Housing, utilities, etc., are the same for two people as it is for one.

Food is more expensive for one as, unless you buy in bulk, the price goes up

and there is also more wastage.[119]

3.84

Similarly, Mrs Margaret Ryan relayed her experience on the widow

allowance. She had not been employed since 1994 but the passing of her husband

in 2005 changed her financial situation dramatically. Although she qualifies

for the widows allowance ($424.30 per fortnight), as she does not receive a

pension she is ineligible for many of the pensioner concessions such as on

council rates, water rates, telephone bills and utility expenses.[120]

3.85

The inquiry also received evidence that in many cases widowed pensioners

face additional expenses with a much reduced income. It was argued that widowed

women are required to finance house and car maintenance and repairs that

previously were undertaken by their late husbands.[121]

Additional payments and taxation benefits

3.86

Over the past 10 years, the Government has increased the disposable

incomes of age pension recipients through bonuses and supplementary payments,

particularly those designed to assist in meeting the costs of utilities and

other large fixed expenditure. The

value of these payments has increased the real value of the pension by

$2 558.60 per year. These payments include:

- The Aged Persons Savings Bonus and the Self-Funded Retirees

Supplementary Bonus in 2001 to enhance retirement savings and income (up to a

maximum of $1000 and $2000 respectively)

- the One-Off Payment to the Aged in 2001 worth $300 for those on

pensions or low incomes

- the Utilities Allowance from 2004 (indexed to CPI and paid in two

instalments each year with the March 2007 instalment valued at $53)

- the Senior Concession Allowance from 2004 to compensate for the

lower accessibility to concessions (as at July 2007 worth $214 per year)

- one-off payments to Older Australians in 2006 and 2007 to meet

household bills

- additional payments to carers from 2004 to those receiving the

Carer Payment (up to $1000 or $600 per carer).[122]

3.87

Other payments that may be available to older people include the bereavement

payment, carer allowance, carer payment pension bonus scheme, pensioner

education supplement, remote area allowance and rent assistance. There is also

the disability support pension, lump sum advance payment, partner allowance,

pension loan scheme, utilities allowance and widow allowance.[123]

3.88

The Pension Bonus Scheme provides for a one-off, tax-free lump sum to

people who receive the age pension if they have deferred claiming the age

pension to continue working. According to FACSIA, the average payment is

$12 292 and there are currently 62 756 registered on the scheme. The

average bonus provides a substantial addition to eligible pensioners'

retirement savings and is approximately one third of the total savings for a

maximum rate pensioner's average assets above the family home.[124]

3.89

Aged & Community Care Victoria (ACCV) and the Wide Bay Women's

Health Centre highlighted the value of the one-off lump sum payment of $500 to

all seniors in the May 2007 budget. They argued that this constituted a relief

to many residents in aged care, but would have been of greater benefit if

introduced earlier and that it was not sufficient to cover all increasing

costs.[125]

Similarly, the Ethnic Communities' Council of Victoria argued that the payment

did not provide a sustainable solution to cost pressures on older Australians

and difficulties experienced by those dependent on the age pension.[126]

The Superannuated Commonwealth Officers' Association argued that one-off

bonuses have provided important assistance to retirees. However, it was argued

that they are insufficient to alleviate ongoing weekly budget pressures.[127]

Conclusion

3.90

The evidence before the committee is highly persuasive that the real

incomes of recipients of the age pension and superannuation have experienced

substantial growth over the past decade over increases in inflation. In the

case of the age pension, the indexation of pension levels to MTAWE has been

responsible for a substantial increase in the real value of the pension. In

part, this has been the result of the growth in real wages that has partly been

a product of the Government's workplace relations reform over the past 11

years. Similarly, since the introduction of compulsory superannuation in 1992,

the rise in the level of the guarantee in 2002 and the growth in real wages,

superannuation balances have inexorably grown.

3.91

However, the capacity of retirees to afford rises in the cost of living

also depends on various other factors, including the suitability of the level

of the retirement payment. Some of the submissions to the inquiry disputed the

appropriateness of the current level of retirement benefits, most notably the age

pension, though no submissions identified a more specific replacement level.

Similarly, no evidence was provided to the committee to justify how the current

levels of payments were arrived upon or their suitability in meeting the costs

of living. The FACSIA submission discussion of adequacy of retirement income

levels was confined to replacement rates, rather than the amount required for a

certain standard of living.[128]

3.92

It is not evident to the committee that the current pension levels

provide or ever provided a sufficient income with which to accommodate the

costs of living. It is clear that a review is needed to ascertain what level of

payment is required to achieve a subsistence level and – as discussed below –

determine a method for adjusting this payment level to meet actual living cost

increases. This may alleviate the need for some of the one-off payments that

have been essential for older people to meet cost of living pressures over

recent years and at the same time avoid the administrative costs associated

with processing one-off payments. The necessity of such one-off payments suggests

there are problems with the existing level of income payments. It is important

to note, as was submitted by the Thirroul Retired Mineworkers' Association,

retired people do not have the same capacity as working Australians to seek a

better paying job, an additional job or extra hours to earn supplementary

income to cover rises.[129]

3.93

The committee accepts that many retirees feel financial stress and must

exhibit great care in managing their incomes and expenses. In many respects

older people, especially those on pensions, have demonstrated substantial

financial prudence. The Australian Family Association submitted that older

Australians are better equipped than other low income earners to cope with

rises in household costs.[130]

However, the committee has particular concerns about some segments of the

retired population. In particular, it has concerns about the adequacy of the

single pension to provide the necessary assistance in providing even a basic

subsistence living without assistance from charities, family or friends. The

committee considers that the single pension's proportion of the couple pension

needs to be reviewed with a view to lifting it to achieve greater equity.

3.94

Other factors influencing the capacity of retirees to afford the costs

of living include the availability and indexation of concessional arrangements,

retirees' individual circumstances- especially home ownership status - and the

fluctuations in particular lifestyle and essential costs. These will be

explored in later chapters of this report.

3.95

Along with concerns about the adequacy of pension and other payment

levels is concern with how they are updated over time. The committee considers

it important that the indexation arrangements for government benefits reflect

the cost pressures associated with those households. Although the pensioner

cost index has been similar to CPI cost fluctuations, since 2001 the age

pensioner cost index has consistently been higher than the CPI (see figure 2). In

particular, age pensioners are on a subsistence income and even a small

discrepancy between the CPI and household living costs can cause substantial

financial stress. Such stress will particularly be felt if in future wage

increases moderate, removing for pensioners the insulating effect of MTAWE

indexation. Older people have a much more limited capacity to improve their

financial situations. Therefore, if those discrepancies continue over the

course of a number of years, as has been the case with the age pension, the

recipients of those benefits will find it increasingly difficult to avoid

experiencing financial stress. Consequently, an analysis of expenditure

patterns specific to older demographics should be conducted to ascertain

divergences from CPI, as well as the impact of continual divergence, even if

minor. The use of the household expenditure survey for assessing age pensioner

and self-funded retiree households should be investigated with consideration

given to concerns raised during the inquiry about the use of this measure.

3.96

As discussed earlier in this chapter, it is unclear why retirees

receiving government payments are subjected to different indexation mechanisms.

Although this has clear implications for the Government's budget, this practice

is inconsistent with principles of equity and fairness, and undermines the

maintenance of the comparative value of many retirees' incomes. This was made

apparent during the course of the inquiry when the Coalition Government agreed

to change the indexation for the remaining veterans' affairs disability rates

to bring them into line with the higher of the CPI or MTAWE. The FACSIA submission

to the inquiry made an excellent case for the benefits that have accrued to

recipients of the age pension as a result of indexation of the MTAWE. However,

this also underscored the increasing divergence between the recipients of this

indexation method, and retirees and older people whose incomes are simply

indexed to the CPI.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page