Chapter 1 - Introduction

Terms of reference

1.1

On 14 June 2007 the Senate referred the issue of the cost of living

pressures for older Australians to the Committee for inquiry and report by 13 September 2007. The reporting date was subsequently extended to the last sitting day in

March 2008. Following the 2007 election and change in government the inquiry

was formally re-adopted by the Senate on 14 February with a reporting date

of 20 March 2008. The full terms of reference for the inquiry required the

committee to inquire into and report on the following matters:

- the cost of living pressures on older Australians, both pensioners and

self-funded retirees, including:

- the impact of recent movements in the price of essentials, such as

petrol and food,

- the costs of running household utilities, such as gas and electricity,

and

- the cost of receiving adequate dental care;

- the impact of these cost pressures on the living standards of older

Australians and their ability to participate in the community;

- the impact of these cost pressures on older Australians and their

families, including caring for their grandchildren and social isolation;

- the adequacy of current tax, superannuation, pension and concession

arrangements for older Australians to meet these costs; and

- review the impact of government policies and assistance introduced

across all portfolio areas over the past 10 years which have had an impact on

the cost of living for older Australians.

Conduct of the inquiry

1.2

The inquiry was advertised in The Australian newspaper and on the

committee's website. Invitations to provide a submission were also sent to government

institutions, community groups and other interested stakeholders, commentators

and organisations. The committee received 239 public submissions and 21

confidential submissions. A list of the individuals and organisations that made

public submissions to the inquiry has been included as Appendix 1.

1.3

The committee held public hearings in Melbourne on 23 August 2007, Canberra on 20 September 2007 and Brisbane on 8 February 2008. The list of witnesses who gave evidence to the committee at the public hearings has

been provided in Appendix 2. Copies of the Hansard transcript are

available through links at https://www.aph.gov.au/Senate/committee/clac_ctte/older_austs_living_costs/hearings/index.htm.

Acknowledgement

1.4

The committee received substantial assistance during the inquiry and

thanks those organisations and individuals who made submissions, gave evidence

at the public hearings and otherwise provided assistance.

Structure of the report

1.5

The report has been structured into eight chapters, which discuss the

key income and cost pressures faced by older people, their consequences for

quality of life and community participation, and key government policies and

initiatives that impact on these issues. The inquiry was undertaken prior to

the change of government following the 2007 election. References to government

policies in accordance with term of reference (e) refer to the former Coalition

Government. An update on the policy initiatives of the new Labor Government

since the election is at Appendix 3.

1.6

This chapter provides the context for the inquiry including details regarding

its conduct, the terms of reference and background on the ageing population. Chapter 2

outlines the general financial situation of older people, particularly with

respect to assets and debt levels. Chapter 3 provides a review of the various

income streams available to older people, notably pensions and superannuation,

and their adequacy. It also reviews the other payments available and the

prevailing indexation methodology that applies to incomes and payments. Chapter

4 discusses the concessions and rebates provided to older people, their

significance for affording the costs of living and issues surrounding their

indexation. The array of cost pressures faced by older people is outlined in

chapter 5. This includes general inflationary pressures, the expenditure

patterns of older people, as well as movements in the prices of specific goods

and services. Chapter 6 outlines the quality of life experienced by older

people, especially as a result of caring responsibilities and rising cost

pressures, as well as their effect on community participation and social

isolation. A general review of government initiatives and policies to assist

older people in meeting cost of living pressures is provided in chapter 7. Chapter

8 summarises the committee's view and provides recommendations on possible

policy initiatives and areas for further investigation.

Background

Defining older people

1.7

As was mentioned in the submission from the Department of Families,

Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FACSIA)[1]

and provided in evidence to the inquiry by a range of witnesses, identifying

and defining retirees and older people has become more complex. Most of the

submissions did not clearly define older people. However, unless otherwise

stated, in this report older people are considered to include Australians in

retirement or of retirement age. Retirement age includes men of 65 or over, men

in receipt of a veterans' service pension aged 60 or over, women aged 63.5 and

over and women in receipt of a veterans' service pension aged 60 or over. The

Committee acknowledges that National Seniors represents people aged 50 and over

and that their background is across the board.

1.8

There is now a substantial emphasis on managing retirement, career

egress and departure from the workforce. Retirement is no longer a fixed date

whereby individuals stop working, but often now involves continued work in some

capacity to suit lifestyle or financial imperatives. Consequently, the

demographics of retirees and older people incorporate diverse segments of the

population, distinct age-cohorts and people of different financial means. For

instance, despite the nominal retirement ages of 65 for men and 63.5 for women,

24 per cent of Australians aged 45‑64 have completely retired and 9 per

cent are partly retired.[2]

Demographic change and economic and

social challenges

1.9

Living standards and their sustainability for older people are of

growing importance to Australian society. This is due to Australia's

anticipated demographic change over the coming decades, which will result in a

higher proportion of older people in the population than ever before. This is a

common trend among Western countries as fertility rates fall and life

expectancy increases, especially as a result of medical breakthroughs,

technological progress, higher incomes and less manually intensive labour. Life

expectancy has been extended to 80 for men and 84 for women.[3]

At the same time, years spent in retirement have increased to 16.8 years for

men and 22.6 years for women.[4]

It is important to note that these demographic characteristics do not yet hold

true for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

1.10

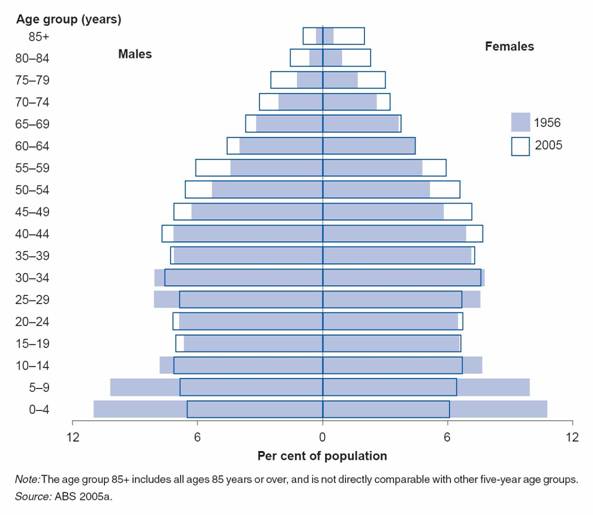

The 2007 Intergenerational Report reported that the proportion of

the population over 65 will double to approximately 25 per cent over the next

40 years. During this period, total labour force participation rates are

expected to decline as a result of the majority of this age-group entering

retirement.[5]

This shift in the age structure of the economy will continue the trend over the

last fifty years captured in Figure 1.1. Currently, there are 5.25 people of working

age in the labour market for every person aged 65 or more. However, if we

assume current working age participation rates continue, this will fall to 2.2

by 2050-51. The ageing of the population will disproportionately affect some States,

with South Australia and Tasmania particularly affected following their historical

propensity to have younger people migrate.[6]

Figure 1.1:

Age structure of the Australian population, 1956 and 2005

Source: AIHW, Australia's Health 2006, p.16.

1.11

These shifts in Australia's demography have various potential impacts,

especially on the performance of the economy, the characteristics of the

electorate, the nature of services required, as well as costs associated with

health, aged care, pensions and other aspects of public administration. The

sustainability of economic growth will be put under pressure as a result of

lower labour force growth, lower productivity, skills shortages and budget

pressures, as older people require greater government spending than younger

ones. Spending on age pensions is expected to rise from 2.9 per cent to 4.6 per

cent of GDP between 2002 and 2042, with rises in the number of eligible

recipients (though offset to a certain extent by enhanced superannuation

accumulation). Similarly, health and aged care spending is projected to rise

from 4 per cent to 8.1 per cent of GDP over this period, as older people have

greater requirements for medical treatment and pharmaceuticals. The lower

labour market participation that would ensue will be ameliorated to an extent

by a (declining) pool of new young workers, increasing participation from

women, immigration, improved education and the consequent greater participation

rates created, and greater encouragement for older people to work.[7]

The significance of cost of living

rises for older people

1.12

The terms of reference for the inquiry are fundamentally aimed at

assessing the standards of living for older people, the capacity of the

government to influence these factors and the efficacy of past measures taken

for this purpose. There are various factors relevant to calculating standards

of living that are intangible and difficult to measure, such as social

networks. For this reason, the terms of reference seek to ascertain the effect

of cost pressures on some of these aspects of community participation. Clearly,

cost of living pressures are fundamental factors in determining the proportion

of income and expenditure required on essentials, the remaining resources for

disposable income and discretionary spending.[8]

1.13

Since the early 1990s, Australia has experienced continuous economic

growth, moderate inflation, high business investment, improved wages, record

low unemployment and sustainable enhancements in living standards.[9]

However, the strength of the economy has highlighted the need to ensure that

all Australians have shared in the benefits and that certain segments have not

been specifically disadvantaged or left behind. Economic growth can sometimes be

associated with rises in the cost of living, which can be particularly felt by

those on lower incomes, such as pensioners and self-funded retirees.

1.14

Of particular importance to this inquiry, older people, and particularly

retirees, are often more vulnerable to rises in the costs of living than many

other people. Those that are still working have limited time to improve their

financial situation before entering retirement. Those that are in retirement

often receive fixed incomes and can be extremely sensitive to even small rises

in the cost of living. Consequently, this report explores the general change to

costs of living that have been experienced across the Australian community, the

financial capacity of older people to meet these costs and the impact on living

standards and quality of life.

1.15

The financial well-being of older people depends on numerous factors,

which will be explored throughout this report and include degree of wealth,

retirement income, availability of concessions and costs incurred. Older people

represent a very diverse group, which means that their well-being depends on

their personal circumstances. However, there are various trends common to the

demographic, which are affecting these issues. The FACSIA submission to the

inquiry acknowledged that the needs of older Australians are diverse, and their

circumstances are not homogenous, and provided a statistical snapshot of the

general characteristics of older people. These include that older persons are

on average wealthier, have lower levels of debt, have high rates of home

ownership, have disposable incomes that are approximately half of the

disposable incomes of all households, and tend to report experiencing higher

levels of prosperity and lower levels of financial stress than other groups.[10]

1.16

FACSIA also argued older people were less likely than other demographics

to experience financial stress. The level of financial stress declines with age

to about 5 per cent in those over 70. Other findings of its research included

that older people have very low levels of subjective poverty. That is, very few

(less than two per cent) consider themselves to be poor.[11]

1.17

However, these findings were contradicted in personal evidence provided

to the inquiry by many submissions from older people and community

organisations involved in the provision of services for older people. St

Vincent de Paul Society research into cost pressures on various households

since 1990 concluded:

Increased cost pressures have disproportionately impacted upon various

households depending upon the stages of their life cycles and income source. It

[St Vincent de Paul's report: Winners and Losers: the Story of

Costs, Social Policy Issues Paper 2] finds that since 1990 there has been a

growth in inequality due to changes in the cost burdens of various goods and

services. Of particular concern is the impact these cost pressures have on the

aged, parents and those reliant on the rental housing market and public

transport.[12]

Conclusion

1.18

The demographic change anticipated in Australia over the coming decades

has highlighted the importance of this inquiry. The shrinking of the labour

force and increased proportion of people in retirement will have substantial

impacts on the costs of public administration and the quality of life of older

people.

1.19

Also, the contradictory evidence highlighted above regarding the general

financial situation and well-being of older people has reinforced the

importance of the inquiry and was characteristic of the broader evidence

presented to the committee. In part, this was the result of different focuses

and methodologies employed in the research. It also reflected distinct findings

when personal and anecdotal evidence was compared to broader statistical

analysis and general overviews of the older population. This has highlighted

the different demographics, entitlements, financial situations and quality of

life characterising different segments of the older population.

1.20

Evidence before the committee highlighted that older Australians from

culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds have complex needs. It is

important that those delivering services are conscious of the cultural and

linguistic diversity of older Australians. It needs to be recognised that the

homogeneity of particular culture groups also varies and it should not be

assumed that all members of the group hold the same values and beliefs. Service

provides need to recognise that not be aware of all the potential linguistic

and cultural barriers to ensure they provide effective and appropriate

assistance.[13]

1.21

Many older Australians who speak English as a second language revert to

their primary language as they age. Service providers need to be conscious of

this fact and tailor services to ensure that any language barriers can be

overcome.

1.22

The committee also heard that many elderly Indigenous Australians have

complex health needs. There is a need for Aboriginal people to have timely

access to aged care services and other supports. The appropriateness of those

services can be diminished without attention to individual needs and

responsiveness.[14]

1.23

The following chapters of this report examine the differing circumstances

that highlight the distinct experiences of different segments of the older

population in relation to cost of living pressures. They will focus on key

aspects of coping with cost of living pressures including the incomes and

wealth of older people, the role played by concessions and subsidies, the

movement in the costs of living both recently and over the past decade, as well

as the impact these factors have on quality of life and community

participation.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page