Chapter 5 - Other issues raised in the inquiry

5.1

Improving cancer outcomes is a multifactorial field

that extends far beyond the scope of this inquiry. While the Committee's

investigations were necessarily focussed by the terms of reference, a number of

specific issues relating to cancer treatment and care were raised in

submissions and at the hearings. These are briefly discussed in this chapter.

Early detection through screening programs

Access to free mammograms

5.2

The issue of providing free mammograms for women outside

the target ages, through the national breast cancer screening program, was

raised.

5.3

The Department of Health and Ageing advised that BreastScreen

Australia actively targets women aged 50-69 years, but women aged 40-49 and

over 70 years are also eligible to attend.

5.4

This policy is in line with international evidence

which demonstrates that breast cancer screening is most effective in the 50-69

year age group. BreastScreen Australia

is a joint Commonwealth, State and Territory funded program. Funding is

provided by the Commonwealth through the Public Health Outcome Funding

Agreements. The Agreements are bilateral funding agreements between the

Commonwealth and each State and Territory Government. The agreements provide

State and Territory Governments with broadbanded (pooled) funding linked to the

achievement of outcomes in a range of public health programs including breast

cancer screening.

5.5

An article in the March 2002 edition of the Medical Journal of Australia reports on

outcomes of a systematic review of screening mammography in women 70 years and

over. The review concludes that:

- Age is the strongest risk factor for breast

cancer, as indicated by the increasing number of cancers detected across age

groups - however, because older women at a higher risk of death from other

causes, they may only experience the downsides of screening, and not live long

enough to experience the benefits; and

- Women aged 70 years and over, in consultation

with their doctor, may want to decide for themselves whether to continue

mammographic screening.[313]

5.6

This is consistent with current BreastScreen Australia

policy, although individual States and Territories have different practices in

relation to service provision for women over 70 years of age. All women over

the age of 70 years can make an appointment and attend any BreastScreen

Australia service across Australia.

5.7

All eligible women aged 50-69 years who already attend

BreastScreen Australia

services are reinvited to attend for breast cancer screening every two years.

However, there are differences between jurisdictions as to when women are no

longer invited to attend for breast cancer screening. Where States and

Territories do cease to reinvite after women have reached an upper age limit,

letters are sent to women affected outlining the reasons why they will not be

reinvited in the future but that they are free to call and make an appointment

for a two-yearly mammogram if they wish.[314]

Access to free mammograms once

diagnosed with breast cancer

5.8

Witnesses raised the issue of their ability to access

breast cancer screening through BreastScreen Australia

following a diagnosis of breast cancer.[315]

My breast cancer was detected by BreastScreen and I found they

provided an efficient service of the highest professional standard. So I was understandably

surprised when I was advised that my follow up mammograms would not occur at

Breastscreen, but on a referral from my surgeon to a private Radiologist...

When I made my appointment with this private radiologist, I was

informed that the mammogram and ultrasound would cost $314-00, payable at the

time of service. Fortunately at the time, I was in a position to meet such a

financial demand, but I know of many women who would find an up front payment

difficult under any circumstances. The benefit I received from Medicare for

this service was $164-60, leaving my family out of pocket $149-40. This is

obviously a huge burden for many women on low or no incomes; it is a pressing

social issue for women who have no direct access to money, which is not uncommon

when many women are forced to take long periods off work to undergo cancer

treatment plans.[316]

5.9

The BreastScreen Australia Program, as a population

screening program, is aimed at well women, without symptoms. BreastScreen Australia

services recommend that women who have had breast cancer in the past and have

had surgery to remove a lump or for a mastectomy continue to visit their breast

specialist for their regular mammograms. Reasons for this include:

- If a woman has had breast cancer and surgery to

remove a lump, special techniques and procedures may be required, such as

detailed pictures of the treated part of the breast. These special procedures

are not offered at a screening visit as BreastScreen Australia is set up to

provide mammograms to detect the apparent early signs of breast cancer in women

with no symptoms.

- If a woman has breast cancer, regular check-ups

should involve a thorough clinical examination by a doctor, annual mammograms

and any other test that may be required. BreastScreen Australia only provides

screening mammograms.

5.10

State and Territory BreastScreen Programs are

responsible for determining their own policies for making services available

for women who have been diagnosed with and treated for breast cancer. Some

States take women who have had treatment for breast cancer back into the

screening program after a specified period of time, others take such women back

if they have a letter from their treating surgeon indicating that it is

appropriate for that woman to return to biennial mammographic screening.

5.11

The Committee is also aware that the Cancer Funding

Reform Project, reporting through the Health Reform Agenda Working Group to

Australian Health Ministers is examining a range of strategic funding issues

associated with the provision of cancer care. The project will investigate the

current funding arrangements for cancer treatment in the Australian health

system across the public and private sectors.

Recommendation 30

5.12 The Committee recommends that the target age groups for

BreastScreen Australia

and the National Cervical Screening Program should be reviewed regularly, given

the increasing trends in life expectancy for Australian women. In addition, a

review should be conducted of how women outside the age limits are made aware

of their cancer risk.

Access to breast prostheses and lymphoedema sleeves

5.13

Issues relating to access to breast prostheses and

lymphoedema sleeves were raised in evidence.[317]

5.14

Ms Crossing

explained that if a women has a mastectomy they need a breast prosthesis so

their spinal alignment does not become compromised and cause other health

problems. She reported that access to breast prostheses after a mastectomy is

not consistent between States. The same difficulties apply regarding access to lymphoedema

sleeves which are necessary to treat 'painful swelling of the arm'.[318]

5.15

The Department

of Health and Ageing advised that the Medicare Benefits arrangements are

designed to provide assistance to people who incur medical expenses in respect

of clinically relevant professional services that are contained in the Medicare

Benefits Schedule, and rendered by or on behalf of qualified medical

practitioners. Therefore Medicare benefits are not payable for the costs of

aids and appliances, including breast prostheses and lymphoedema sleeves.

5.16

However, the Commonwealth does provide funding for the

surgical implantation procedure, under the Medicare Benefits Schedule for

privately insured patients (excluding those seeking implantation for purely

cosmetic purposes) and for public patients (including the prostheses) through

the Australian Health Care Agreements.

5.17

The Plastic and Reconstructive Subgroup of the Medicare

Benefits Schedule contains a number of services which provide for the surgical

implantation, removal and/or replacement of breast prostheses as well as breast

reconstruction procedures for women who have undergone mastectomy.

5.18

In addition, private health insurance funds are

currently required under the Surgically Implanted Prostheses, Human Tissue

Items and Other Medical Devices (Schedule 5) of the National Health Act 1953 to

fully fund prostheses items that are provided as part of an episode of hospital

care, such as breast implants.

5.19

The funding for breast implants listed in Schedule 5 is

limited to patients who have undergone specific Medicare Benefits Schedule

procedures; it does not cover the prostheses provided for cosmetic procedures

such as breast enlargement. The range of surgically implanted breast prostheses

listed on the Prostheses Schedule includes both saline and silicone-gel filled

prostheses. The Commonwealth has had no role in the funding of products currently

listed on Schedule 5. This has been a matter between the health funds and the

supplier of the product.

5.20

For external prostheses (not surgically implanted) like

breast prostheses and lymphoedema sleeves, private health insurance funds may

be able to provide a rebate for the cost of the prostheses as part of their

ancillary cover.

5.21

If the person does not have private health insurance,

help may be available from State/Territory governments, such as the Program for

Aids for Disabled People in New South Wales.

Access to PET scans for people with recurrent or advanced breast cancer

5.22

The issue of access to Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

scans for people with recurrent or advanced breast cancer was raised.[319] Ms Crossing noted that although Positron

Emission Tomography scans for most cancers are funded by the Commonwealth, they

are not funded for breast cancer even though a great deal of evidence shows it

is an important tool for following and staging the course of advanced breast

cancer. Cost implications for the patient are significant with Ms Crossing

indicating that 'it is $900 out of your pocket and that is a huge sum of money

for most women faced with this particular situation'.[320]

5.23

The Department of Health and Ageing advised that there

are currently 13 PET scanners in Australia.

Nine scanners receive Commonwealth funding in eight facilities and all eight facilities

are participating in an evaluation of PET clinical and cost effectiveness.

Results from this program are expected to become available from mid 2006 and

will inform the decisions about future PET funding.

5.24

The Department also advised that the average Medicare Benefits

Schedule fee for a PET scan is around $950 and that conditions of Commonwealth

funding specify that scans are performed at no or minimal out of pocket cost to

the patient. PET effectiveness and cost effectiveness in the management of

breast cancer would need to be considered by the Medical Services Advisory

Committee before any decisions about public funding could be made. The role of

the Medicare Service Advisory Committee is to advise the Federal Minister for

Health and Ageing on the evidence relating to the safety, effectiveness and

cost effectiveness of new medical technologies and procedures.[321]

Adolescent cancer care

5.25

The provision of appropriate cancer care services for

adolescents and for young adults with cancer, an age group for whom the

incidence of cancer is increasing, was raised in evidence by a number of people

including witnesses from CanTeen and the Centre for Children's Cancer and Blood

Disorders at Sydney Children's Hospital:

Published Australian data, which mirrors overseas data,

indicates that during the past decade alone cancer incidence has increased by

30 per cent in young people aged between 10 and 24 years. This increased

incidence of cancer in adolescents and young adults is higher than in any other

age group.[322]

5.26

The Committee was advised that there is also growing

concern internationally for the adolescent and young adult cancer population

and mounting evidence for targeting improvements for this patient group.[323]

5.27

While cure rates both for younger children and older

adults with cancer have improved, the same is not true for adolescent cancer

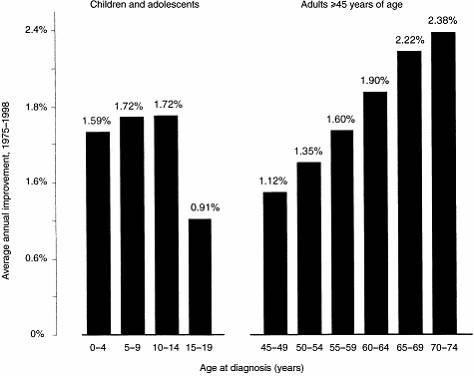

patients as shown in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1: Management of cancer in adolescents

Source: Albritton K and Bleyer WA, 'The management of cancer in the older adolescent', European Journal of Cancer vol.39 2003,

pp.2584-2599.

5.28

Issues for adolescents as described for the Committee include

firstly, that access to clinical trials for adolescents with cancer is very

poor which means they are less likely to have access to state-of-the-art

treatment. Secondly, they are less likely to be treated in specialised

multidisciplinary cancer care units where the best results are achieved. There

are no guidelines for the referral of adolescents and young adults with cancer

to specialist care which means they are randomly referred to either paediatric

or adult cancer physicians. Dr O'Brien

indicated that:

Survival rates for children with leukaemia or cancer are higher

when treatment is supervised by a tertiary paediatric cancer centre, where

treatment is planned and supervised by a multidisciplinary team comprising both

medical, surgical and radiation oncological disciplines, and where treatment

utilises active trials conducted by international paediatric cooperative

groups.[324]

5.29

A recent Victorian study was quoted as demonstrating

that treating adolescents with a particular type of bone tumour in a paediatric

regime improved survival rates by 50 per cent.[325] Other evidence based on studies by

McTiernan in the UK

and referred to by witnesses reported that international studies have shown

significant improvements in outcomes for adolescents and young adults treated

on clinical trials. The review by McTiernan confirmed that adolescents with

acute lymphocytic leukaemia, non-hodgkins lymphoma, nephroblastoma and

rhabdomysarcoma as well as medulloblastoma have all shown a significant

survival advantage when treated on trial protocols within specialist centres,

compared to those that are not.[326]

Recommendation 31

5.30 The Committee recommends that Cancer Australia

consider the development of appropriate referral pathways that take account of

the particular difficulties confronted by adolescents with cancer.

Damien's story –

The needs of adolescents

In April 1999 I was diagnosed with a bone cancer

called Osteosarcoma, in my left knee. At the time I was 15 years old and was

treated at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne for 9 months.

When I was diagnosed I was a typical 15 year old. I

was very fit and healthy and had no history of cancer in my family. I didn’t

know anything about cancer or any of the treatments for it. It was something I

had never come across before.

From the time ‘something showed up on the x-ray’ until

the time I finished my treatment I wasn’t at school. This meant that I didn’t

get the opportunity to spend time with my friends like a ‘normal’ teenager

would. Even outside of school my friends didn’t come and visit me. I assume

because they didn’t know what to say. This meant that I didn’t have anyone who

was my age that I could talk to about what was happening to me. Even within the

hospital there were very few teenagers of my age due to that fact, I was being

treated at a children’s hospital...

Soon after I finished my treatment, I attended a camp

for Patient Members of CanTeen. This was the first opportunity I had had to

talk to people my age about what had happened in the last 9 months of my life

and how it would effect the rest of my life. I got to meet people who had ‘been

there and done that’ and see how they had continued with their lives...

I believe it is hard enough for a young person to grow

up and cope with the normal changes that happen in their life. Throw in a

diagnosis of cancer, and it throws the young person out of their normal life,

and into hospital. Being able to talk to people my age that had been through

similar experiences was able to bring back some kind of ‘normalness’ into my

life.

Submission 51, p.14 (CanTeen Australia).

5.31

CanTeen, the organisation that supports young people

living with cancer, indicated that 12-24 year olds undergoing treatment were

not surviving as well, or being supported as well, as were children between the

ages of 1-12.[327]

5.32

The psychosocial care needs of adolescents with cancer

differ from those of an adult or a child and are not being addressed. Witnesses,

including young patients, emphasised that when you are a teenage patient, being

treated in a children's environment adds to the frustrations in terms of the

physical facilities and the support services. These frustrations are similar if

the adolescents were treated in a ward with very sick adults. The personal

experience of a teenage cancer patient being treated in a children's hospital

was described by Ms Michels:

The women's and children's hospital has a toy room, a great

resource for little kids. The walls are painted with huge bright murals of

clowns, fairies and under-the-seas themes, all directed at small children. The

prints in the rooms are of kittens and Peter

Rabbit, and the video collection had much to

be desired. Once you have sifted through the Wiggles and stories like that, you

might get to view something like Toy Story. I wanted a couch to sit on and play

music that I like listening to. I found myself spending a lot of time in the

'quiet room', which is a room with two couches and no bright paintings or

anything. The small children did not go in there as it was not exciting.[328]

Ms

Michels then described her experience when

treated in an adult hospital a few years later:

I met a lot of lovely people and their families but I struggled

a lot because of the age gap. I did not feel like we could talk about the stuff

that teenagers talk about in front of adults. It was hard for my friends to

stay positive around me as I was surrounded by sick and older people lying in

beds.[329]

5.33

Witnesses told the Committee there appeared to be

inflexibility in decisions and policies as to where adolescents are treated

which could impact on outcomes. One example was given for NSW: 'if you are aged

15 and 11 months then you can go to a children's hospital. If you are 16 then

you cannot be admitted to a children's hospital for a new diagnosis of cancer'.[330] Ms

Ewing noted that the Cancer Control Network:

acknowledges that adolescents with cancer "present a

challenge that is not adequately addressed by current systems or models of care

in Australia".

[White 2002]. This situation is likely to have occurred because the care of

adolescent patients is often seen as neither the preserve of paediatric or

adult services [Leonard et al 1995], and consequently these people fall into

the void between.[331]

5.34

It was suggested to the Committee that the way to

address this issue is for the establishment of specialised teenage cancer units

where there could be collaboration between both paediatric and adult cancer

specialists. Such a unit would utilise a multidisciplinary team to deliver

appropriate medical and psychosocial care.[332]

The needs of

adolescents

The needs of adolescents are different to those of

both children and adults, as there is this middle ground. We are not dependent,

like children are on their parents, but we do not have people dependent on us.

We have all different issues. By having adolescent wards you would be

surrounded by people where you fit in, you feel like you belong and you are not

alone. You could have the same interests. Friendships would naturally form and

support would be given. Adolescents would be surrounded by others that are

dealing with similar situations in and out of hospital. They can relate to what

is going on, as they are going through the same things. There would be a

positive environment with others who they can feel comfortable and relaxed

amongst. We can share, listen, have fun, joke, be ourselves, relax, learn, heal

and grow throughout this. Talking is a great healer for cancer patients because

it releases disturbing thoughts bottled up inside. It is proven beyond a doubt

that the mind can help heal the body when you are thinking positively. Cancer

patients and other young people living with cancer have a genuine understanding

of each other’s situation and what we are going through.

Committee Hansard 19.4.05, p.63 (Miss

Lauren Michels).

5.35

The Committee concluded that it was very important that

information was provided as soon as possible about the current treatment

profile in Australia

for this age group, how it compares with other countries and how many clinical

trials are available and being accessed. In terms of the environments in which

these young people are being treated, often for long periods of time, it was

important to ask the State and Territory health departments how they are addressing

the issue.

Recommendation 32

5.36

The Committee recommends that State and Territory

Governments recognise the difficulties experienced by adolescent cancer

patients being placed with inappropriate age groups and examine the feasibility

of establishing specialised adolescent cancer care units in public hospitals.

Research

5.37

The Committee noted that cancer research in Australia

is funded by a number of bodies including the Commonwealth, through the NHMRC,

as well as State and Territory governments, Cancer Councils and charities and

others.

5.38

The Commonwealth Government announced as part of the

2005-06 Budget that funding will be provided over four years for a dedicated

cancer research budget and that seed funding is to be provided to establish a National

Research Centre for Asbestos Related Diseases.

5.39

The Committee was advised that the Cancer Institute

New South Wales has a major research program and has invested research

fellowships, infrastructure that enables researchers to access equipment and expertise,

and translational (bench to bedside) research.[333]

5.40

The Victorian Department of Human Services has

established a Cancer Research Working Group. The group provides advice on the

better integration, coordination and development of cancer research and promotes

communication between research centres and health services to facilitate the

translation of cancer research into clinical practice.[334]

5.41

The Cancer Institute New South Wales

has recommended that the Commonwealth government consider a more strategic focus

for cancer research.[335] The Institute

suggested that, in addition to the traditional areas funded by the NHMRC,

further research should be directed towards translational research, health

services research, screening and early detection, and clinical trials.

Clinical Trials

5.42

Clinical trials are fundamental to establishing whether

there is benefit in new treatments. Participation in clinical trials needs to

be encouraged as there is evidence that people receive better care and have

longer survival if enrolled in trials, though there is a considerable disparity

between the numbers enrolled.[336]

5.43

Witnesses expressed concern at the relatively low

enrolment of people in clinical trials, with the enrolment of adults being

around two to three per cent though 20 to 30 per cent are eligible.[337] This contrasts with children, where

every child is considered for a trial and over 50 per cent are entered.

5.44

The Cancer Institute New South Wales

stated that national cancer clinical trials are poorly funded and operate on

grants from philanthropy. The Institute called for the provision of support to

these groups from governments throughout Australia.[338]

5.45

The Committee noted that in response to the low

enrolments in clinical trials, the Cancer Institute New South Wales

established The Clinical Trials Program which has four main aims, to:

- Introduce and study new cancer treatments;

- Increase participation rates in cancer clinical

trials;

- Promote a culture of research and innovation in

our cancer service programs; and

- Connect cancer clinical trials in New South

Wales to key national and international trials.

5.46

A Clinical Trials Office has been established to assist

the Cancer Institute New South Wales

in achieving the above listed aims. The Clinical Trials Office will endeavour

to provide high quality cancer clinical trial infrastructure for New

South Wales, managing the initiatives identified as a

result of workshops and discussions with key stakeholders and groups.[339]

5.47

The Committee also noted that the Commonwealth is

committing significant funding over the next four years to provide infrastructure

grants for cancer clinical trials through the Strengthening Cancer Care

Initiative.[340]

Data

5.48

Many witnesses identified gaps in cancer data, which if

addressed could lead to improvements to both service planning and treatment for

cancer patients.

5.49

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

identified three major gaps in national data on services and treatment options.

5.50

The first related to the lack of national data on

hospital outpatient services for cancer. The AIHW indicated that from July 2005

a collection of hospital outpatient occasions of service delivery for

chemotherapy and radiation oncology would commence for the principal referral

and other major hospitals in each State.

5.51

The second area is data on the stage of cancer, a

pre-requisite to interpreting changes in survival and to analysing the effects

of changes in treatment and services. The need for staging data was also

strongly supported by Dr Threlfall,

Manager and Principal Medical Officer, Western Australia Cancer Registry.[341] The AIHW has acknowledged that some

work was occurring in the area of staging data. For example:

- The National Cancer Control Initiative has

developed a national clinical cancer core data set. The data set has been

endorsed by the National Health Data Committee of the Australian Health

Ministers Advisory Committee. The National Cancer Control Initiative has also

undertaken some pilot work in Western Australia and the Northern Territory on

the feasibility of collecting staging data.[342]

- The Cancer Institute New South Wales has

commenced a program for the collection of a minimum data set of 45 items on

every cancer patient in New South Wales. The minimum data set is targeted at

the patient's journey and is expected to be rolled out within a 12 month

period.[343]

- The Victorian Department of Human Services has

established a Data/Information Working Group that is promoting the collection

of the National Cancer Control Initiative's Minimum Data Set.[344]

5.52

The AIHW acknowledged that the standardisation of

staging data across States and Territories would take some time and that the

coding from the detailed to the aggregated data set would be very costly.[345]

5.53

The third gap relates to the lack of linkage between

existing data sets. There are a number of individual data sets from the

Medicare Benefits Schedule and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, the Health

Insurance Commission data bases, and hospital records, where there is little

linkage of these data bases. Commonwealth statisticians and the ABS are working

on protocols on how the ethical linkage of data can be undertaken, taking into

account relevant privacy legislation.[346]

5.54

The Committee heard that there was a major gap in the

collection of data on cancer staging. Data on the stage of cancer is a

pre-requisite to interpreting changes in survival and to analysing the effects

of changes in treatment and services. The AIHW acknowledged that while work is

being undertaken in this area, the standardisation of staging data across

States and Territories would take some time and would be costly. Given the

importance of cancer staging data, the Committee makes the following

recommendation.

Recommendation 33

5.55 The Committee recommends that Cancer Australia,

in consultation with State and Territory Governments and the Australian

Institute of Health and Welfare, take a leadership role in coordinating the

development of a national approach to the collection of cancer staging data.

Palliative care

5.56

Palliative care was raised by a number of witnesses as

an area requiring greater attention due to the increasing incidence of cancer.

As stated by Professor Kricker

'the fact that 36 000 die is not reflected in the state of development of

the palliative care services. It is a crying need'.[347]

5.57

Palliative care is a relatively new discipline in Australia's

health care system and aims to improve the quality of life of people with

life-limiting conditions.[348] To a

great extent, hospice palliative care in Australia

has been driven by community demand through non-government organisations led by

doctors, nurses, other committed health professionals and members of the

public.

5.58

The provision of good palliative care is not just for

the benefit of the terminally ill patient. Providing good palliative care at

the end of a cancer patient's journey has measurable health outcomes in terms

of the unpaid carers. Professor Currow

stated:

I would like to reflect on the fact that good palliative care is

not a black hole into which we pour money; it is something with measurable

health outcomes that are felt long after the death of a person. The care giver

impact is positively affected by the involvement of palliative services and

that effect has hangover, if you will, that lasts for many years after the

death of the person who has had a life-limiting illness. The very small

investment that we make in palliative care has an enormous benefit for the

health of the whole community when measured in those sorts of parameters.[349]

5.59

It is evident from the growth in the demand for

domiciliary palliative care throughout Australia that patients in the final

stage of the cancer journey appreciate the option of being able to die at home

or, at least, spend as much time as possible there. Dr

Helen Manion

reported that a World Health Organisation survey showed that 80 per cent of

people have the wish to be able to remain in their own homes to die but the

reality is that the majority of cancer patients die in an institution.[350]

5.60

Despite improvements in survival rates, Professor

Currow stated that 'one in two people diagnosed

with a solid cancer will still have their life substantially shortened by that

in 2005. So we need excellent support and end of life care'. Currently the

majority of patients (greater than 80 percent in most cases) referred to

palliative care services in Australia

have cancer.[351] Given the increasing

numbers of people with cancer, without recognition of this resource need, the

planning of future cancer services across the country will continue to be ad

hoc. Professor Currow stated that 'unless we start to plan for the future in a

very proactive way and ensure that every position has the flow-on effects of

all the allied health, nursing and medical needs – and equalling that with the

challenge of ensuring that we are providing infrastructure across the continuum

of care; so in the community, in in-patient settings and in out-patient

settings – we are going to have problems in the future'.[352]

5.61

Professor Currow

mentioned the variation across Australia

in metropolitan, rural, regional and remote Australia

in accessing specialised palliative care services.[353] This disparity was highlighted by

investigators at the University of Western Australia who conducted research

which found that one third of people who died of cancer had not receive

specialist palliative care. They found that people were less likely to receive

specialist palliative care services if they were aged 84 years or over; female;

Aboriginal; living in remote areas; or socioeconomically disadvantaged. Their

research also found that use of specialist palliative care services reduced the

likelihood of dying in a hospital or in a residential aged care facility,

suggesting that the use of specialist palliative care services potentially

reduces the demand on other hospital beds.[354]

5.62

Submissions suggested that the use of care coordinators

is important to ensure that all patients are referred to a specialist

palliative care service.[355]

5.63

The role of the carer of a terminally ill patient has

been recognised by the Australian government. Some carers qualify for financial

entitlements through Centrelink with the Carer Payment for those who are not

able to work due to their caring responsibilities and the Carer Allowance,

which helps parents or carers to care for adults with a disability at home.[356]

5.64

The Commonwealth is 'providing $201.2m throughout the

five years of the Australian Health Care Agreements (2003-08) for palliative

care. Of this, $188m is broadly allocated on a per capita basis to States and

Territories for continued service provision, and $13.2m for the Australian

Government to implement a national program of initiatives. In the 2002 Federal

Budget, the Australian Government announced a further $55m over four years

(2002-06) for national activity to improve the standard to palliative care

offered in local communities'.[357]

5.65

To meet the demand for palliative care in the home,

witnesses raised concerns over the availability and supply of some drugs.[358] Drugs that are available in a

hospital are not automatically available for a patient being looked after at

home. The Pharmacy Guild recommended that 'the range of medication used in

palliative care listed in the PBS be broadened to assist in providing wider

access to medication at an affordable price for patients who wish to remain in

the community during the terminal phases of their lives'. The Guild

acknowledged that there have been recent listings of several medications but is

concerned that preparations currently listed are not adequate, citing Midazolam

and Ketalar as examples. They explained that 'there is little incentive for

manufacturers to apply for PBS listings for these drugs for innovative uses

such as in palliative care' and recommended that the dual listing of

medications used in palliative care should be investigated.[359]

5.66

The Committee questioned the Department of Health and

Ageing about why a drug that has gone through an approval process for a

specific reason, and when it may then need to be used in a different dose or in

a different treatment, needs to go through the process again as it is very

expensive and there is marginal, if any, profit for the manufacturer to do it.

5.67

In response to this issue about drugs on the palliative

care list, Dr Lopert from the Department of Health and Ageing, advised that

they are 'aware that there is concern over availability of some medications on

the palliative care list, but their lack of availability of the palliative care

list reflects that fact that they do not have marketing approval for the

indications that are relevant to the palliative care setting'. Dr Lopert stated

that the process is a safeguard as 'the broader issue from the PBS point of

view as opposed to the registration point of view is that it is inappropriate

to provide reimbursement for drugs for an indication outside that for which it

is approved for marketing in Australia – that is one of the principles

underlying the PBS...The issue of approval for indications other than those for

which it is registered is an issue for the TGA rather than the pharmaceutical

benefits branch'. When questioned specifically about Midazolam, Dr

Lopert stated 'the approved indication is

actually quite narrow. It is not approved for an indication that could be

conceivably appropriate for use in a palliative care setting – it talks about

use as an adjunct in anaesthesia for a surgical procedure'.[360]

5.68

The Committee noted there was some confusion about the

authority process for palliative prescriptions, particularly for the first

dose. The Department of Health and Ageing provided the following advice:

Requirements for prescriptions for palliative care medicines to

be authorised by the Health Insurance Commission were put in place to minimise

use outside the intended population whilst ensuring access to patients with the

greatest need. It would be impractical to not require authorisation of the 'initial'

supply, whilst requiring authorisation for continuing supply. First, without

the authority mechanism it would not be possible to monitor where an initial

supply has occurred. Second, it is most likely that medical

practitioners would continue to prescribe under the 'initial' supply

arrangement without ever seeking authority to prescribe a continuing supply.[361]

5.69

The Department also advised that the work of the

Palliative Care Medications Working Group continues, with a further medication,

Paracetamol Sustained Release, included on the palliative care section of the

PBS in April 2005. A further list of 10 medications have now been

prioritised by the Palliative Care Medications Working Group, and will be

progressed for listing in coming months. For example, Flinders University of

South Australia has now been engaged to support the generation of evidence and

data to support registration and listing of these medications under the Scheme.

In addition to the above, the Working Group is working on a number of strategies

to: support quality use of medications through education and support for GPs

and other primary health care workers, in the

management and care of palliative care patients in the community; and increase

the awareness of health professionals and the broader community on medications

currently available and how they can be accessed.

5.70

Dr Page

raised the issue of access to palliative care in regional and rural areas. She

stated that 'palliative care and pain management is becoming an increasingly

specialised field which, again, translates very poorly into rural and remote

areas. I am very distressed to say that the worst palliative care services are

often for children's cancers'. Dr Page

also stated that 'palliative care is something which should be available in

every country town' and highlighted 'there are a vast number of GPs out there

with palliative care skills and advanced level pain management skills'.[362]

5.71

Palliative Care Australia,

the peak national organisation representing palliative care in Australia

released a detailed set of standards for providing quality palliative care for

all Australians on 23 May 2005.

Workshops to promote and explain the new standards are currently underway

throughout the country.

5.72

The Committee noted that as the Australian population

ages and the incidence of cancer increases, the community's need for quality,

long-term palliative care will grow. It is essential that the health care

system (including public, private and not-for-profit) is well equipped to

provide quality palliative care services that meet new national standards.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page