CHAPTER 8

THE NATIONAL SUICIDE PREVENTION STRATEGY

Introduction

8.1

This chapter will address term of reference (h) the effectiveness of the

National Suicide Prevention Strategy (NSPS) in achieving its aims and

objectives, and any barriers to its progress.

National Suicide Prevention

Strategy

8.2

The current NSPS is a program under the COAG National Action Plan for

Mental Health 2006-11. The 2006-07 Federal Budget committed the Commonwealth

funding which included $62.4 million to expand the NSPP to $127.1 million

between 2006-07 and 2011-12.[1]

The five year goal of the NSPS is to reduce deaths by suicide across the

population and among at risk groups and to reduce suicidal behaviour by:

Adopting a whole of community approach to suicide prevention

to extend and enhance public understanding of suicide and its causes;

Enhancing resilience, resourcefulness and social

connectedness in people, families and communities to protect against the risk

factors for suicide; and

Increasing support available to people, families and

communities affected by suicide or suicidal behaviour.[2]

8.3

DoHA described the current NSPS as having four inter-related components.

The first is the LIFE Framework which 'provides national policy for action

based on the best available evidence to guide activities aimed at reducing the

rate at which people take their own lives'.[3]

The second was the National Suicide Prevention Strategy Action Framework which

provides a time limited workplan for taking forward suicide prevention and

investment. The Action Framework was developed in collaboration with ASPAC and '...will

effectively steer the NSPS and NSPP' until 2011. The third, the National Suicide

Prevention Program (NSPP), is the Commonwealth funding program for suicide

prevention activities which is administered by DoHA. The final component was mechanisms

to promote alignment with and enhance state and territory suicide prevention

activities, particularly to progress the relevant actions of related national

frameworks, such as the COAG National Action Plan for Mental Health 2006-2011 and the Fourth

National Mental Health Plan 2009-14.[4]

Suicide prevention in Australia

Department of Health and Ageing

8.4

DoHA has primary responsibility for suicide prevention at the

Commonwealth level but outlined the broad range of services and programs

(usually in the area of mental health) which assist those at risk of suicide. They

stated:

Mental health services and programs, broader health

initiatives such as indigenous health programs, and drug and alcohol support

also comprise an important platform from which DOHA administered programs

contribute to efforts to prevent suicide and support people at risk of suicidal

behaviour. Other Government portfolios similarly administer a broad range of

mainstream programs which contribute to supporting individuals at risk and

protecting against factors which may be associated with suicidality.[5]

8.5

In the area of mental health services DoHA highlighted a recent review

which indicated expenditure had increased to $1.9 billion in 2007-08. They

noted that while only 1 per cent of funding is 'directly contributed to the

NSPS, a large amount of funds are provided for programs and services which

support suicide prevention efforts'.[6]

These included mental health services under the MBS and programs such as ATAPS,

training for mental health professionals, mental health promotion (including the

National Depression Initiative), mental health programs funded for groups at

high risk of suicide (such as indigenous specific mental health programs),

early intervention programs (such as headspace) as well as programs for parents

(perinatal Depression Initiative) and children (KidsMatter Early Childhood).[7]

They also highlighted a range of supported telephone and web based crisis

support and self help therapies. The investment in the National Drug and

Alcohol Strategy was also highlighted as 'extremely relevant to suicide

prevention efforts'.

Broader investment in Indigenous health programs, including

social and emotional wellbeing activities also contributes to suicide

prevention efforts targeting Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders.[8]

Department of Families, Housing,

Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA)

8.6

The FaHCSIA submission also outlined a range of programs that, while not

specifically focused on suicide prevention, also contribute collaterally to the

prevention of suicide through promoting resilience and protective factors. They

stated:

FaHCSIA programs play a crucial role in providing early

intervention services for individuals and families from high risk vulnerable

groups. Many FaHCSIA programs aim to build individual and community resilience,

which is core to suicide prevention. Programs also provide services that can

ultimately reduce suicide risk and increase protective factors. Research suggests

that being part of a cohesive and supportive family unit is an important

protective factor for children and young people, helping them to better cope

with any stressors or adversity they may encounter.[9]

8.7

In particular FaHCSIA funds Mensline Australia delivered by Crisis

Support Services, an initiative which offers a range of services and programs

to support men in managing family and relationship difficulties.[10]

Department of Veteran's Affairs

(DVA)

8.8

DVA provides training for the peer support of veterans at risk of

suicide through Operation Life offering ASIST to veterans or support provided

through Family Relationship Centres to help families manage and resolve

conflict.[11]

8.9

As part of an election commitment the Commonwealth Government committed

to conducting a study that examines the broad issue of suicide in the

ex-service community, including a number of specific cases of suicide over the

last three years. The Suicide Study report conducted by Professor David Dunt,

together with the Government’s response, was publicly released on 4 May 2009.

The recommendations cover a wide range of matters, including strengthening

mental health programs, including suicide prevention, the use of experienced

case coordinators for complex cases, and ensuring that administrative processes

are more ‘user-friendly’.

8.10

The Government allocated $9.5 million over four years to implement the

recommendations in order to strengthen and improve the range of mental health

services provided, particularly in relation to suicide prevention, to support

the veteran community.[12]

8.11

DVA outlined a number of suicide prevention and mental health projects

directed to the veteran community. These included Operation Life, a

framework for action to prevent suicide and promote mental health and

resilience across the veteran community. A major part of this framework

included suicide prevention workshops as well as the provision of information

on treatment services that are available to the veteran community. Also

mentioned was the Veterans and Veterans Families Counselling Service (VVCS), a specialised

national service that provides counselling and support to Australian veteran, peacekeepers,

their families and eligible Australian Defence Force personnel.[13]

Other

8.12

Other areas noted included the role of the Department of Education,

Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) which administers a range of

services to assist people with mental illness and those at risk of suicide. Another

example was that Centrelink social workers referred 3,463 persons 'as a result

of being at risk of suicide' and 30,650 more broadly with 'mental health

issues'.[14]

States and Territories

8.13

The State and Territory governments have a range of suicide prevention

strategies and programs.

8.14

The Queensland Government stated that it planned to finalise the

Queensland Government Suicide Prevention Action Plan in 2010 following the

previous strategies Reducing Suicide: the Queensland Government Suicide

Prevention Strategy 2003-2008 (QGSPS) and Queensland Government Youth

Suicide Prevention Strategy 1998-2003. It noted that over the past 12 years

the Queensland Government has allocated an annual budget of $2 million directly

to cross-government suicide prevention initiatives.[15]

8.15

The NSW Government stated that it is in the process of developing a new

NSW whole-of-government 5-year suicide prevention strategy which will follow on

from the 1999 NSW Suicide Prevention Strategy: we can make a difference.[16]

8.16

The WA Ministerial Council for Suicide Prevention is an advisory body to

the WA Minister for Mental Health. The Council has been given a mandate to

oversee the implementation of the WA State Suicide Prevention Strategy

2009-2013 which has been committed $15 million over four years.[17]

8.17

The SA Government noted that SA Health is developing a statewide suicide

strategy '...that will focus on social justice, coordination, collaboration,

partnerships and building on existing programs'.[18]

The strategy will be released in late 2010.[19]

The SA Government also outlined recent funding for several suicide prevention

and support programs including to Beyondblue, SQUARE, Mental Health First Aid

(delivered by Relationships Australia SA) and to Centacare Suicide Prevention

Program ASCEND.[20]

8.18

The Victorian Mental Health Reform Strategy 2000-2019 Because mental

health matters states a goal of the strategy is to:

Renew our suicide prevention plan, Next Steps: Victoria’s

suicide prevention action plan, using the new national framework to

strengthen our ability to identify and respond to risk factors and emerging

trends in suicide behaviour and suicide prevention.[21]

8.19

In October 2009, the Tasmanian Government released Building the

Foundations for Mental Health and Wellbeing, a Strategic Framework and Action

Plan for Implementing Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention (PPEI)

Approaches in Tasmania (the Framework). A priority under the framework was

the development of a Suicide Prevention Strategy for Tasmania. This has been

commissioned and is due for completion in June 2010.[22]

8.20

The NT Government noted that the NT Strategic Framework for Suicide

Prevention commenced in 2003. A NT Suicide Prevention Action Plan 2009

-2011 was launched in March 2009. The Plan provides a whole of Government

response to guide directions in suicide prevention over the next three years.

New funding of $330 000 has been allocated by the Department of Health and

Families from January 2009 to June 2010 to progress a range of new initiatives

including '...increased training programs in suicide prevention and self injury

and the development of suicide and bereavement support resources'.[23]

8.21

The ACT Government indicated it had recently launched a new suicide

prevention strategy Managing the Risk of Suicide: A Suicide Prevention

Strategy for the ACT 2009-2014 which '...was strongly aligned to the LIFE

Framework'.[24]

Coordination and collaboration.

8.22

A criticism of the NSPS was that it had resulted in fragmented services

for those at risk of suicide. The Suicide is Preventable submission argued that

'roles, responsibilities and accountabilities are poorly defined...there is no

agency at a national or state/territory level with the mandate to address

suicide and suicide prevention'.[25]

8.23

The Suicide is Preventable submission listed how responsibility for

suicide was distributed:

- Mortality data collection – this is distributed across an array

of organisations.

- Morbidity data – the AIHW and the Injury Surveillance Unit at

Flinders University.

- Funding for program initiatives – a person or small group of

public servants within health departments in the Commonwealth Government and in

some State and Territory governments. These staff are generally located within

the Mental Health Branches. They generally provide small scale grants and the

few national initiatives receive little funding.

- Research – some health departments program occasional grants for

‘research’. Other funds are provided on a competitive basis from the usual

national funding sources. Annual funding would be less than $10m, on the

available evidence.

- Services – crisis lines, support services, prevention,

intervention and bereavement activities are carried out by a range of non-government

organisations (NGOs) – many are parties to or supporters of this Submission.

- Advocacy – SPA

- Self-help groups and other support groups – small networks of

community groups. [26]

8.24

Similarly, Lifeline Australia stated that despite the significant

achievements of the NSPS, the 'execution of the strategy has often been

fragmented and lacks a clear vision for how all levels of government, community

stakeholders and consumers can work together in a co-ordinated way to think

strategically, plan effectively and achieve good outcomes'. Lifeline Australia recommended

the vertical integration of the NSPS by engaging all levels of government in

strategic development and implementation. It also noted the limited processes

or structures for developing systematic, cross sector collaboration. They

stated:

While entities like Suicide Prevention Australia do provide

forums for sharing of ideas, programs and research, more substantial

collaborative structures and mechanisms are needed to work with governments,

stakeholders, communities and consumers around planning, developing and

implementing suicide prevention strategy.[27]

8.25

Professor John Mendoza also highlighted problems with service

coordination between the programs funded by Commonwealth and the States and

Territories. He stated:

We have ridiculous overlaps and duplications of service, and

then we have massive gaps. As one consumer that I work with regularly describes

it, it is a lucky dip out there if you can get any access to mental health

services. It is a really lucky dip if you get access to quality mental health

services, ones that actually are effective. In this area, in relation to people

experiencing suicide ideation and suicidal behaviour, it is even a greater

lucky dip to actually score the sort of service that is going to work.[28]

8.26

Professor Graham Martin highlighted that there was the risk suicide

prevention activities could be subsumed into the mental health agenda and

'...lost as an issue'. He also commented on Commonwealth-State service provision

coordination:

Several programs in Far North Queensland were funded by the

Commonwealth but nobody at the state level seemed to know much about them—what

they were doing or how they were working. So there was then duplication, or

attempts at duplication.[29]

8.27

DoHA noted that alignment between Commonwealth, State and Territory

suicide prevention activities, coordinating investment and activities, was

being progressed through the Fourth National Mental Health Plan.[30]

This includes action to:

Coordinate state, territory and Commonwealth suicide

prevention activities through a nationally agreed suicide prevention framework

to improve efforts to identify people at risk of suicide and improve the

effectiveness of services and support available to them.[31]

8.28

DoHA stated that '...effort has gone into jointly planning Australian

Government suicide prevention investment with states and territories,

particularly under the COAG National Action Plan for Mental Health 2006-11 and work has begun

towards a single national suicide prevention framework'.[32]

However they acknowledged that efforts to align '...suicide prevention activity across

the Commonwealth and with state and territory government investment in suicide prevention

will continue to be both a priority and a challenge'.[33]

Governance and accountability

8.29

The Suicide is Preventable submission argued that the NSPS was not

actually a 'national strategy'. They commented:

It is not a national strategy in the way that other national

strategies are formal agreements signed by all Australian governments and, in

some cases, by community or industry stakeholders. The current strategy, which

carries that name, is the strategy of the Commonwealth Department of Health and

Ageing.[34]

8.30

Similarly the Suicide Prevention Taskforce argued the LIFE Framework had

served as a proxy for the NSPS. They said:

The NSPS is not a national policy or strategy endorsed by all

governments through COAG. It has never been endorsed by the Australian Health

Ministers' Conference or other inter-government forum. Nor is it a

whole-of-Commonwealth Government policy or strategy as it does not have the

engagement in development or deployment of a whole-of-government strategy. It

is a strategy developed by and deployed by the Commonwealth Department of

Health and Ageing.[35]

8.31

The ACT Government noted there was confusion within the community

concerning the status of the NSPS, specifically around whether or not there is

a national strategy. They stated:

Within the community, some view the Living Is For Everyone: a

framework for prevention of suicide in Australia as ‘the strategy’. However,

the Commonwealth refers to this as a ‘supporting resource’... The lack of clarity

concerning the content of the National Suicide Prevention Strategy is a

significant barrier to its successful implementation[36]

8.32

The ACT Government recommended that the Commonwealth provide greater leadership

and guidance surrounding strategies for national suicide prevention by

developing a clear strategy document which sets out actions to be implemented,

an implementation strategy and mechanisms for consistent data collection.

8.33

Some considered the role of government departments was limiting suicide

prevention activities. SPA commented that ...previous instability of

executive-level staffing arrangements within departments responsible for the

oversight of the NSPS has also produced an environment that has not been

entirely favourable to the development of a cohesive Australian suicide and

suicide prevention research agenda.'[37]

Similarly the Suicide Prevention Taskforce argued that 'changes in personnel,

machinery of government and policy frameworks have impeded progress and

outcomes'. They stated:

Health Departments have limitations in being able to provide

the leadership for a whole-of-government issue like suicide prevention and

bring about the structural and broader societal changes necessary to tackle

complex issues like suicide and they are limited in their ability to implement

whole-of-community programs.[38]

8.34

SPA commented that historically there had been broad support for the

NSPS objectives. However they stated:

In 2008, criticism was expressed by some suicide prevention

sector stakeholders towards national suicide prevention policy settings.

Feedback from the consultations undertaken as part of the independent

evaluation of SPA clearly indicated a growing sense of frustration and malaise

with regards to policy formulation and progress in Australia, including what

was perceived by some members to be a disregard of the informed advice of

experts, the evidence and/or the views of the sector and a continuing

marginalisation of the issue of suicide prevention more generally...[39]

8.35

The Suicide Prevention Taskforce submission proposed a new national

governance and accountability structure with four key organisations to

implement a 'coordinated multi-strategy approach to suicide prevention'. One of

the rationales for this approach was that suicide was not only a health issues

and there were a number of sectors '... private, public and community - with a

stake in suicide and suicide prevention'. In summary these proposed structure

would be:

- A new coordinating body which would monitor the performance of

subsidiary entities in the new structure and approve strategic priorities for

suicide prevention

- A peak advocacy body to advocate on behalf of service providers

and those affected by suicide.

-

A suicide prevention council and resource centre which would

develop information and resources for service providers, develop research

strategy, and develop standards and accreditation.

-

A national foundation in suicide prevention which would raise

funding from a variety of sources and promote awareness.[40]

8.36

Similarly Lifeline Australia recommended the creation of a national

organisation for suicide prevention independent of any specific government

department.[41]

Professor John Mendoza commented:

...we have to invest in new structures, new infrastructure and

invest in what is truly a national strategy, not one that has got the name 'National

Strategy’ but a national strategy that engages not only the other eight

governments in Australia but the sector, the industries, the stakeholders who

really want to see transformation in this area.[42]

8.37

The MHCA also linked better data collection in relation to suicide and

attempted suicide with better governance and accountability.

Robust accountability and transparency means removing the

process whereby governments assess their own performances and measures, and

giving this role to organisations that can provide genuine oversight and

accountability of progress in reducing suicide in Australia.[43]

8.38

Professor Peter Bycroft argued that there were too many vested interests

in control of the decision making process, in key positions of policy advice

and in co-dependency relationships with DoHA. He recommended that the advisory

bodies '... who are instrumental in decisions relating to priorities for policy,

service provision and funding should be arms length from the Department and

should not be dominated by either the medical/clinical professions or academics/researchers

who are major beneficiaries of those funding decisions'.[44]

8.39

Professor Patrick McGorry recommended that an aspirational target should

be set for the reduction in the rate of suicide in Australia. He noted this

target may not be quick to achieve but it would '...really put pressure on us as

a society to significantly reduce the suicide toll as we have been successful

in doing in reducing the road toll over the last couple of decades'.[45]

This is an approach that has been taken overseas. For example, Choose Life: the

national strategy and action plan to prevent suicide in Scotland includes a

target to reduce suicide by 20 per cent over ten years.[46]

8.40

Professor Graham Martin's comparison of national suicide prevention

strategies noted that some overseas jurisdictions have decided on specific

targets for reductions in suicide. He notes that this 'may be a two-edged

sword, on one hand leading to criticism of the government for not achieving a

goal, but it also may very well help with public perceptions, and the public

ownership of, and commitment to, suicide prevention'.[47]

Evaluation of the NSPS

8.41

In 2005 the Commonwealth engaged Urbis Keys Young to conduct an

independent evaluation of the NSPS. The evaluation found NSPS was '...widely

supported and perceived as an appropriate and necessary strategy that addresses

an ongoing community need'. However it also found that 'stronger evidence

regarding the impact and outcomes of NSPS funded projects is required'.

8.42

DoHA noted that a full independent evaluation of the NSPS is planned for

the 2010-11 financial year '...that will provide guidance on the currency and efficacy

of the strategy that will inform the department’s advice to government on any

changes of direction or amendments to the strategy'. [48]

The AISRP argued that evaluating the NSPS was problematic because of the

inaccuracy of ABS data on suicides.[49]

Funding issues

8.43

DoHA stated that the Commonwealth has increased its annual allocation of

funding for specific suicide prevention programs from $8.7 million in 2005-06

to $22.2 million in 2009-10 and that this forms part of a broader investment in

mental health services and programs of $1.9 billion.[50]

It stated '...investment by the Australian Government in suicide prevention has

increased significantly over the last decade, and that there has been no

reduction of effort despite the decline in official data on deaths by suicide'.[51]

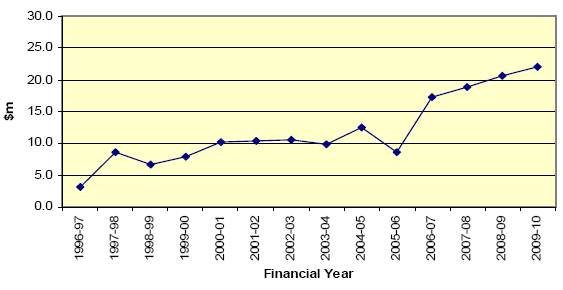

Appropriations by Financial Year for National Youth

Suicide Prevention Strategy (1996-97

to 1998-99

and NSPP (1999-00

to 2009-10)[52]

8.44

However the lack of resources available to implement the NSPS was often

emphasised during the inquiry. For example Lifeline Australia stated that the 'financial

resources allocated to implementing the strategy are meagre in relation to the

scope of the problem...'.[53]

The funding available for suicide prevention was compared to other issues which

received greater levels of public funding such as road safety and cancer. RANZCP

recommended that funding allocated to suicide prevention should be equivalent

to that spent on events and/or illnesses with a similar mortality rate, for

example breast cancer.[54]

8.45

The Suicide is Preventable submission stated there was also a need to '...broaden

the funding base from non-government sources – that is, from community,

philanthropic, unions and other collectives and business sources – to

supplement the contributions made by governments'.[55]

8.46

The approach of the funding projects under the NSPS was also criticised.

The Suicide Prevention Taskforce stated that:

The NSPS approach to funding small scale projects has been

likened to 'spreading confetti across the land'. While this approach of

investing through small grants has developed some capacity in communities to

respond to suicide, few projects have been sustained and even fewer evaluated.[56]

8.47

SPA recommended the funding priorities should be shifted '... from

short-term small scale projects to longer-term investment in projects that

derive sustainable outcomes and include a budget for evaluation of

interventions as an evidence base against which to measure the ongoing

effectiveness of the NSPS'.[57]

8.48

A number of organisations commented that the lack of certainty regarding

funding cycles created problems for the organisations in maintaining staff as

well as the credibility with clients to whom assistance was being directed. The

ACT Government also noted there was a history of mental health programs

developed on a pilot basis, where Commonwealth funding is withdrawn after an

initial period despite positive evaluations. They noted this can have a

significant impact on clients who lose services and for providers who become

disillusioned or are unaware of services because of ongoing changes.[58]

8.49

This view was shared by many organisations which operated suicide

prevention programs. The Integrated Primary Mental Health Service of North East

Victoria emphasised:

We cannot stress enough the need for long term funding for

mental health skilled community workers. Grant funding is inappropriate. Short

term projects are regarded cynically, ‘How long are you lot going to be

around?’. We have learnt that workers need months to years to successfully

be accepted and valued by a community.[59]

8.50

Mr Keith Todd from OzHelp stated:

We lose good, quality people because they have family

themselves. They are probably looking for another job nine months out. They

have families to support and they have to take care of their own

sustainability.[60]

8.51

Similarly, Ms Kerry Graham from the Inspire Foundation commented:

... three-year funding contracts, which are set at the

beginning, do not allow a great deal of flexibility to be highly responsive;

and then, when you are getting to the end of your funding contract, you are putting

most of your efforts into repositioning or demonstrating success, which is very

important, as opposed to being as forward-thinking as you can be...[61]

8.52

Centre of Rural and Remote Mental Health Queensland stated:

Sustainability presents a significant challenge for community

based suicide prevention strategies. Pilot and seeding programmes that do not

have a strategy for longer-term implementation often raise expectations and

needs within communities that are then not met... With short term funding

arrangements, many groups struggle to find new resources. Efforts to

institutionalise programmes may compete with the time-consuming task of

fund-raising during the later stages of projects...There is also a strong

likelihood of a loss of momentum and the departure of key project staff.[62]

8.53

The Urbis Keys Young evaluation identified several aspects of the NSPS

structure and processes that could be strengthened. This included understanding

in the sector of '...funding processes and mechanisms to advise on the progress

and outcomes of NSPS activities and projects (including evaluations of these

projects)'.[63]

During the course of the inquiry the Committee heard from some community

organisations who felt their locally-based and long running programs had been

excluded from consideration for public funding as they did not have the

capacity to write complex competitive tenders.

8.54

DoHA told the Committee that following the open tender process for local

community grants in 2006 'there was some concern from smaller organisations who

were not as good at writing submissions as bigger organisations... worthwhile

small projects felt they could not compete'.[64]

Conclusion

8.55

The Committee understands that work is being undertaken to produce a

single national suicide prevention framework and DoHA has indicated that an

independent evaluation of the NSPS has been scheduled for financial year

2010-2011.

8.56

In the opinion of the Committee the policy documents around the NSPS

(the LIFE Framework resources and the National Suicide Prevention Action

Framework) do not assist understanding of suicide prevention activities in

Australia, particularly given the different strategies being conducted or

developed by the State and Territory governments. There is an opportunity to

simplify these policy documents and promote understanding of the NSPS and

suicide prevention activities in Australia.

Recommendation 37

8.57 The Committee recommends that following extensive consultation with

community stakeholders and service providers, the next National Suicide

Prevention Strategy include a formal signatory commitment as well as an appropriate

allocation of funding through the Council of Australian Governments.

8.58

The Committee is sympathetic to the views of many organisations and

individuals who supported the joint Suicide is Preventable submission and the

proposal that a new governance and accountability structure would assist the

delivery of suicide prevention programs in Australia. However the Committee is

also cautious to support the creation of several interrelated organisations

which may divert resources from suicide prevention activities and programs.

8.59

The Committee was interested in the recent changes to responsibility for

suicide prevention in WA. In that jurisdiction a Ministerial Council for

Suicide Prevention has been charged with overseeing the implementation of the

WA State Suicide Prevention Strategy which would be delivered by a

non-government organisation.[65]

The Committee considers that a greater role could possibly be taken by ASPAC

and the various State and Territory Ministerial Councils for suicide prevention

in developing policy and programs under the NSPS.

Recommendation 38

8.60 The Committee recommends that an independent evaluation of the National

Suicide Prevention Strategy should assess the benefits of a new governance and

accountability structure external to government.

8.61

The Committee accepts the recommendations made in many submissions that

funding for suicide prevention programs, projects and research in Australia be

substantially increased. The Committee recognises that many other public

programs and welfare expenditure operate to limit or decrease the incidence of

suicide and attempted suicide in Australia. In particular, a broad range of

mental health services and programs which function to prevent or treat mental

illness significantly contribute to reducing suicide and attempted suicide.

Similarly many other government services and programs can also be seen as promoting

recognised protective factors and limiting risk factors for suicide.

8.62

Nonetheless the funding for programs which could be described as at 'the

pointy end' of suicide prevention is relatively limited ($22.2 million in

2009-10) when considered against even some of the lower financial cost

estimates of suicide in Australia. Additional public funding directed to

effective programs and projects in this area can literally be considered to be

lifesaving. It is clear to the Committee that the public funding made available

for suicide prevention is not proportionate to the personal, social and

financial impacts of suicide in Australia.

8.63

The Committee also recognises the need to diversify the funding sources

for suicide prevention. In the view of the Committee there is merit in the Suicide

Prevention Taskforce proposal to establish a foundation to encourage other

sources of funding for strategic priorities in research, advocacy and service provision.

Recommendation 39

8.64 The Committee recommends that the Commonwealth government double, at a

minimum, the public funding of the National Suicide Prevention Strategy, with

further increases to be considered as the research and evaluation of suicide

prevention interventions develops.

Recommendation 40

8.65 The Committee recommends that the Commonwealth, State and Territory

governments should facilitate the establishment of a Suicide Prevention

Foundation to raise funding from government, business, community and

philanthropic sources and to direct these resources to priority areas of suicide

prevention awareness, research, advocacy and services.

8.66

The short term funding of programs and projects is an issue with which

the Committee is familiar from previous inquiries. Clearly this approach to

funding cycles allows government some flexibility to change priorities. However

short term funding cycles can be enormously detrimental to the establishment

and ongoing success of projects and programs. Short term funding cycles usually

create additional administrative burdens for projects, disruption for clients

and uncertainty for project employees.

Recommendation 41

8.67 The Committee recommends that, where appropriate, the National Suicide

Prevention Program provide funding to projects in longer cycles to assist the success

and stability of projects for clients and employees.

8.68

The most important measure of the effectiveness of the NSPS is whether

it has reduced the number of suicides in Australia over the period of its

operation. Unfortunately this measure has been obscured by changes to data

collection and uncertainty regarding the underreporting of suicides. The

situation will become clearer as revised data from the ABS is released over the

coming years and trends will be identified. The Committee feels that an

explicit and ambitious target for the reduction in the annual number of suicides

should be included in the NSPS. This target would function to focus the

attention and resources of government and the community on suicide prevention

initiatives.

Recommendation 42

8.69 The Committee recommends that the Commonwealth government as part of a

national strategy with State, Territory and local governments for suicide

prevention set an aspirational target for the reduction of suicide by the year

2020.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page