Chapter 19

International coordination

19.1

A crucial aspect of international peacekeeping operations is the

interaction that takes place between participating nations. Typically, this

interaction is coordinated by global organisations, such as the United Nations

(UN), or by regional organisations—such as the North Atlantic Treaty

Organization (NATO), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) or the

Pacific Islands Forum (PIF).

19.2

This chapter examines Australia's engagement with global and regional

organisations in peacekeeping operations. It first explores Australia's

engagement with the UN before examining Australia's contribution to regional

organisations. It concludes by identifying initiatives that could strengthen Australia's

capacity to contribute to global and regional peacekeeping initiatives.

Australia's engagement with the UN

19.3

As outlined in Chapter 2, Australia recognises the important

contribution made by the UN to maintaining international peace and security. Australia

also recognises that the UN remains a key international partner in policy

development and information sharing in peacekeeping.

19.4

Australia supports the activities of the UN in a number of important

ways: it provides personnel for peacekeeping operations, it contributes to the

UN's peacekeeping budget, it participates in discussions about policy

development and, where possible, it contributes to the UN's ongoing reform of

its peacekeeping operations.[1]

19.5

All member states share the costs of UN peacekeeping operations. Australia's

annual share of the UN peacekeeping budget is approximately $100 million. This

equates to a contribution of approximately 1.8 per cent of the approved total

cost.[2]

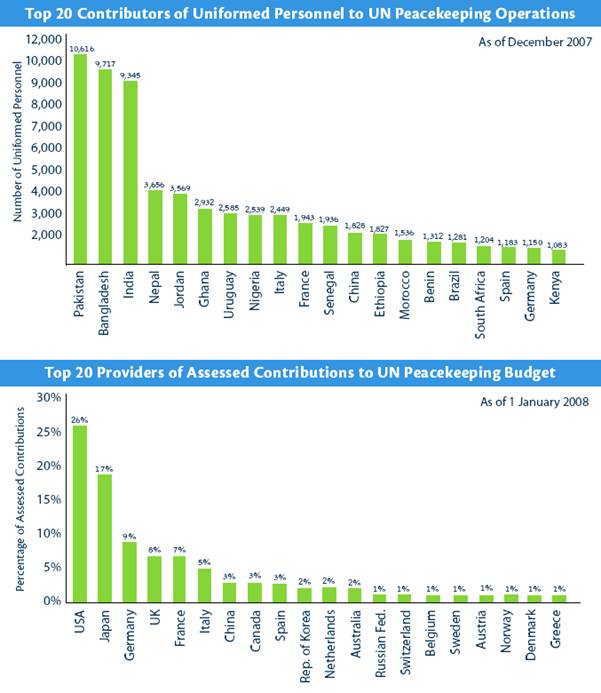

As of January 2008, the top 10 providers of assessed contributions (that is,

non-voluntary financial contributions) to UN peacekeeping operations were: the United

States, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, China, Canada, Spain

and the Republic of Korea.

Contributors to UN peacekeeping operations[3]

19.6

A nation's assessed contribution is determined by the General Assembly. It

takes into account the relative economic wealth of member states with permanent

members of the Security Council required to pay a larger share.

19.7

Regarding the contribution of personnel to UN operations, as of 31 March 20 08, Australia contributed 107 military and police personnel and was ranked 62nd

internationally.[4]

Beyond this commitment, it should also be noted that Australia has over 900

personnel committed to regional peacekeeping operations.

Australia's Permanent Mission to

the UN

19.8

Australia's Permanent Mission to the UN in New York is the key

instrument for Australia's engagement with the UN. It is headed the Ambassador

and Permanent Representative to the UN.

19.9

Staff at the mission are responsible for engaging on a regular basis

with UN bodies and member states on various issues, including UN peacekeeping

reform and the development of doctrine and policy. These staff are seconded

from DFAT, AusAID, Defence and the AFP. DFAT staff monitor and engage in the

work of different committees, including those involved with aspects of

peacekeeping operations; AusAID staff manage engagement with the Peacebuilding

Support Office; and Defence and AFP staff engage with the UN Secretariat on

operational matters.[5]

19.10

In addition, the AFP's Police Adviser liaises with the Department of

Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO), and facilitates engagement in training and

policy. The Police Adviser also represents Australia at the Special Committee

on Peacekeeping (C34).[6]

Agency contact with the UN

19.11

Individual government agencies have direct contact with the UN through

liaison officers; nonetheless, DFAT tends to be the lead government agency in

coordinating Australia's engagement with the UN on peacekeeping issues. For

example, the United Nations Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste (UNMIT) required DFAT

to work closely with the UN Secretariat, operation partners and the Timor-Leste

Government.[7]

19.12

The AFP regularly contributes to the work of the DPKO's best practices

unit, and several AFP officers have held key UN positions, including the Deputy

Senior Police Adviser in Cyprus (UNFICYP).[8]

19.13

AusAID noted its work with the UN Office for the Coordination of

Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), explaining that it had provided funding to OCHA's

Civil–Military Coordination Section in a bid to help achieve more effective

civil–military coordination.[9]

Placements in the UN DPKO

19.14

The UN departments responsible for peacekeeping are the Department of

Peacekeeping Operations and the Department of Field Support (formerly, the

Department of Peacekeeping Operations, DPKO).[10]

19.15

Prior to this restructure, the DPKO had a policy that each member

country could have up to three seconded officers working in the DPKO at any one

time. As at July 2007, Australia had two secondees from the Department of

Defence: one was a training officer in the Training and Evaluation Service and

the other was a planning officer in the Military Planning Service.[11]

The third secondee was from the AFP: Mr Andrew Hughes was appointed in August

2007 to the position of Senior Police Adviser in the DPKO, the most senior

police position in the UN.[12]

In this position, Mr Hughes is responsible for 'coordinating police involvement

in UN peace efforts, including establishing doctrine, procedures and

standards'.[13]

19.16

As at July 2007, there were a further 14 Australian nationals

(non-government employees) working in the DPKO.[14]

Increasing representation in the UN

19.17

Some submitters and witnesses to the inquiry expressed the view that Australia

could increase its representation in the UN, particularly senior staff, and

that more could be done to harness the skills of secondees upon their return.[15]

19.18

Major General Ford claimed that the ADF has a culture that does not

value secondments to the UN:

So first of all there has to be an acceptance that going and

doing a UN assignment is actually good for your career and is as demanding as

being the battery commander or being the brigade major in the deployable force

headquarters up in Brisbane or Townsville. That is not accepted yet. It is not

seen as a good career move to go off and have a posting, in the police or the

military.[16]

19.19

Major General Smith, Austcare, also commented that the ADF needed to be

confident that the personnel selected for UN secondments would return to the

ADF, thereby allowing the organisation to benefit from their experiences:

We just recently sent a major general to the Middle East...I am

talking about the UNTSO, the United Nations Truce Supervision Organisation—for

his terminal posting. I think that is a critical place to have somebody who can

come back to Australia and give us the benefit of his experience there.[17]

19.20

The ADF and DFAT both stated that they would like to see as many

Australians as possible in the UN secretariat, particularly at the more senior

levels.[18]

Lt Gen Gillespie noted that the ADF considers 'very carefully every bid that

we get from the United Nations asking us whether we want to contribute [to] particular

operations and appointments'.[19]

19.21

The current government has identified its membership of the UN as one of

the 'three pillars' of its foreign policy and the Prime Minister has recently

announced that Australia will seek election as a non-permanent member of the UN

Security Council for 2013–2014. The committee also notes that DFAT's Portfolio

Budget Statements 2008–09 states that DFAT 'will seek to secure further senior

Australian representation in the United Nations'.[20]

The committee acknowledges these attempts to further strengthen Australia's

engagement with the UN.

Committee view

19.22

The committee considers that it is in Australia's interests for

government personnel to be seconded to the UN. It also believes that government

departments could be more active in seeking out these opportunities. While the committee

considers that this would be of particular value for senior government

officers, it sees little value in secondments being used as 'terminal

postings'. The committee strongly believes that the knowledge of returning

personnel should be harnessed by the home agency to improve the agency's

understanding of UN processes, and facilitate Australia's UN engagement.

Additionally, such secondments would help develop the capacity of Australian

officers to work with other international organisations such as the World Bank

and the International Monetary Fund.

Recommendation 25

19.23

The committee recommends that Australian government agencies actively

pursue opportunities to second senior officers to the United Nations.

Furthermore, that such secondments form part of a broader departmental and

whole-of-government strategy designed to make better use of the knowledge and

experience gained by seconded officers. In other words, appointments should not

be terminal postings and should be perceived as important and valuable career

opportunities.

Regional engagement

19.24

Although the UN remains the prime organisation for international peace

and security, the increasing number and scope of peace operations has led to a greater

emphasis on regional peacekeeping coalitions and stronger regional engagement. As

noted in Chapter 2, individual countries, regional organisations and coalitions

conduct peacekeeping operations within the framework of Chapter VIII of the UN

Charter. Defence underlined the importance of Australia's engagement in

regional peacekeeping operations:

It is in Australia's interest to actively pursue the enhancement

of regional cooperation in peace operations capability and interoperability.

This has the added benefit of generating regional confidence and enhancing Australia's

international relationships.[21]

19.25

In some cases, where it is vital to Australia's interest to have a

peacekeeping operation in the region, Australia will look to other countries

for both political and material support. For example, the committee has

discussed Australia's successful efforts to marshal international support for

INTERFET. At that time, the then Minister for Foreign Affairs recognised that

INTERFET needed to be 'a multinational force' and expressed his appreciation to

the regional partners for their participation in the force: New Zealand,

Thailand, the Philippines, Singapore and Malaysia. The minister also recognised

the support given to the mission by Korea, China and Japan and assistance provided

by the UK and the US.[22]

19.26

DFAT plays a key role in engaging regional organisations and contributes

to the capacity of these organisations to respond to regional security

challenges.[23]

Other agencies too, such as the ADF and the AFP, continue to build

relationships with partner organisations in the region to prevent and respond

to crises.[24]

19.27

Unlike security arrangements in some other regions—such as NATO in Europe—the

Asia–Pacific does not have a collective security institution to manage conflict.

Peacekeeping arrangements tend to be approached on a case-by-case basis. In

this section of the report, the committee considers the existing forums

contributing to the region's capacity for peacekeeping operations, as well as

other regional engagement initiatives undertaken by Australian government

agencies.

ASEAN Regional Forum

19.28

The ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) seeks to promote open dialogue on

political and security cooperation in the region. It was established at the ASEAN

Ministerial Meeting in Singapore in 1993, and the inaugural meeting of the ARF took

place in Bangkok in July 1994. The objectives of the ARF are to:

- foster constructive dialogue and consultation on political and

security issues of common interest and concern; and

- make significant contributions to efforts towards

confidence-building and preventive diplomacy in the Asia–Pacific region.[25]

19.29

While the ARF provides a structure for improving mutual understanding

and preparedness for peacekeeping operations, it is not a collective security

organisation.[26]

Nevertheless, it has taken some important steps to help coordinate security and

peacekeeping-related endeavours among its members. The ARF encourages closer

military-to-military and civil–military engagement in areas such as disaster

relief and pandemic response. DFAT reported that the general principles being

developed have broader applications to peacekeeping operations.[27]

For example, the first ARF peacekeeping experts group meeting was co-hosted in Malaysia

by Australia and Malaysia in early 2007. The meeting was to share information,

standardise doctrine and develop a better understanding of each country's

approach to peacekeeping and deployment. It was attended by military and

foreign affairs representatives from 24 of the 26 ARF member countries.[28]

DFAT expected that New Zealand and Singapore would host a similar meeting in

2008.[29]

19.30

Defence commented that they were seeking to promote the ARF's capacity:

Our long term goal is the evolution of a regional framework for

standardising approaches to peace operations, conducting multilateral exercises

and the planning and conduct of operations by a unified regional task force. Australia

is promoting within the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) the establishment of a

network of peacekeeping expertise and the development of ASEAN CIMIC standard

operating procedures.[30]

19.31

DFAT made a similar statement about Australia's work within the ARF.[31]

Committee view

19.32

The committee acknowledges Australia's work with like-minded ASEAN

nations to develop a regional peacekeeping capability. It believes that these

endeavours could be consolidated at both planning and operational levels and

sees particular value in Australia seeking to establish joint training

exercises with ASEAN nations.

Pacific Islands Forum

19.33

The Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) is an inter-governmental organisation

which seeks to enhance cooperation between the independent countries of the Pacific.

Founded in 1971 as the South Pacific Forum, PIF is the region’s premier

political and economic policy organisation and has 16 member states. Its

headquarters are in Suva, Fiji, and the forum meets annually to develop

collective responses to regional issues.[32]

19.34

The PIF can mandate peacekeeping operations through the Biketawa

Declaration. The declaration was adopted at the 31st Summit of PIF Leaders in Kiribati

in 2000. It provides 'a mechanism through which [the Forum] can call on members

to uphold democratic principles and to take certain actions, including targeted

measures, if a member state breaches those principles'. The declaration was the

mechanism through which the PIF endorsed RAMSI in 2003.[33]

19.35

RAMSI demonstrates the potential for PIF to take a central role in

promoting peace and stability in the southwest Pacific.[34]

It is a multilateral, regional operation whose legitimacy stems, in large

measure, from the strong regional support for the mission. DFAT emphasised this

point:

The participation since December 2006 of all sixteen Pacific

Island Forum member nations, and successive endorsements of RAMSI by PIF

Leaders' Meetings, and by the Forum Eminent Persons Group, demonstrates the

level of regional support for RAMSI and adds to the mission's credibility as a

regional initiative. The contribution and participation of regional personnel

resulted in a level of ownership of what was perceived to be a regional

solution to a regional problem.[35]

19.36

Even though PIF was instrumental in establishing RAMSI, its role in the

implementation of the mission has, until recently, been limited. A review

undertaken in 2007, which was prompted by the concerns of the Solomon Islands

Government, noted:

...RAMSI lacked a regional oversight

mechanism to anchor RAMSI's regional character not only in terms of its

personnel but also in the way its strategic direction is monitored.[36]

19.37

The review made three critical recommendations:

- the regional character of RAMSI be strengthened, giving PIF a

more prominent and structured role in the mission's oversight and governance;

- a Ministerial Standing Committee be established to provide

strategic oversight of RAMSI and to report annually; and

- the PIF Secretary General endorse the position of RAMSI Special

Coordinator (now nominated by Australia in consultation with Solomon Islands).[37]

19.38

The RAMSI experience highlights the important role PIF can provide in

regional security. It also points to the importance of having good procedures

and mechanisms in place to ensure that regional responses to crises are not

only endorsed at a regional level, but continue to be implemented and monitored

on a regional basis as they progress.

19.39

It is clearly in Australia's national interest that Pacific island

states are politically stable, are supported by good governance programs and

that their citizens have the opportunity to enjoy satisfactory standards of

living. The PIF is the ideal forum through which Australia can assist the

region build an effective peacekeeping, peacebuilding capacity. The committee

notes that the Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, announced in March 2008 that Australia

was seeking to host the 2009 Pacific Islands Forum.[38]

Proposed Australia–Pacific Islands

Council

19.40

In several previous reports, the committee has commented on the role of

people-to-people, business-to-business and organisation-to-organisation links

in sustaining healthy, strong and mutually beneficial relationships with other

countries in the region.[39]

Such connections are essential to creating an environment in which Australia is

better able to elicit support from its neighbours for a regional peacekeeping

operation and sustain that commitment for the duration of the mission.

19.41

In its 2003 report on Australia's relations with Papua New Guinea and

the island states of the south-west Pacific, the committee recommended that the

government establish an Australia–Pacific Council. The purpose of the council

was to 'advance the interests of Australia and the countries of the Pacific

region by initiating and supporting activities designed to enhance awareness,

understanding and interaction between the peoples and institutions of the

region'.[40]

In its response to the committee's recommendation, the government recognised

the value of broadening and promoting Australia's relations with Pacific island

countries. It informed the committee that any future consideration of an

Australia–Pacific Council 'would need to examine both the feasibility and

potential benefits of such a council, including financial and other resource

requirements'.[41]

19.42

The committee notes that an independent taskforce has recently published

a special report on the future directions of Australia's Pacific islands policy.

Published through the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), the report recommends

the establishment of an Australia–Pacific Islands Council.[42]

19.43

The committee's 2007 report on Australia's public diplomacy noted that Australia

currently has nine bilateral foundations, councils and institutes (FCIs) that

work with a particular country or region of the world. Although they have their

own mission statements, in general, their overarching objective is to develop

and strengthen people-to-people links and to foster greater mutual

understanding.[43]

The committee acknowledges that such a council would help to develop people-to-people

contacts and important institutional and cultural linkages within the region.

19.44

The committee cannot see any significant obstacles to the establishment

of an Australia–Pacific Islands Council. Moreover, the benefits that would flow

from a council made up of Australians keen to promote people-to-people and

institutional links with these island nations are obvious. The committee

considers the proposal worthy of government consideration. It suggests that the

Australian Government consider establishing an Australia–Pacific Islands

Council to build and strengthen people-to-people and institutional links between

Australia and the island states of the Pacific.

Limits to regional capacity

19.45

While there are great benefits attached to having small regional

countries contribute to regional peacekeeping operations, Australia has to be

mindful that nations with small police forces and limited civil services do not

overcommit.

19.46

Associate Professor Wainwright argued that Australia must be very

careful that small countries do not have their domestic capabilities undermined

or 'gutted' to service regional operations:

...while I think it is important to build up regional resources

and to have regional dynamics and cooperation working well, we should be under

no illusion as to how much then we can seek to draw from our regional partners.

I do not think it is in their interests that we always take their best and

brightest for these regional endeavours. That said, sometimes it makes good

sense for some of the few police perhaps from some of the countries in the

region to be involved in these regional operations because then, like in the

labour mobility instance, they bring you skills and they develop new skills

which they can take home and use in their home. So that is a benefit as well.[44]

19.47

In recognition of the smaller capacity of Australia's near neighbours in

the Pacific, a sensible regional approach to peacekeeping would include working

to enhance the local capacity that exists within potential contributing

countries. Associate Professor Wainwright suggested that Australia could start

by 'developing public servant capability', including an institution of public

management. She further considered that this could be done through PIF, through

the education and perhaps exchange of regional public servants to Australia.[45]

19.48

Major General Ford commented that sometimes regional capacity may be

limited in which case UN support may be required:

A regional operation will often have to react fairly quickly to

a situation and then seek authority to continue that operation from the United

Nations under chapter VIII—and then possibly even be supported or replaced by a

United Nations organisation if they do not have the capacity to continue to

solve the problem.[46]

19.49

Major General Ford's comment illustrates the importance of maintaining

strong links between the UN and regional associations.

Committee view

19.50

In Chapter 16, the committee discussed how peacekeeping missions can

best establish legitimacy and credibility in host countries. It noted that Australia's

involvement in the missions in East Timor and Solomon Islands was at the

invitation of the governments of those countries. Even so, evidence suggested

that Australia's prominence in the region may, in the minds of some, create a

perception of Australian dominance in a peacekeeping operation and undermine

the credibility of the mission.

19.51

Thus the active engagement of other countries in the southwest Pacific in

regional peacekeeping activities would help to counter this perception. The committee

believes that it is important for the Australian Government to encourage

greater representation of PIF member states in regional peacekeeping

operations. It recognises, however, that these states have limited capacity.

Even so, there is scope for Australia to help build a regional peacekeeping

capacity by assisting individual states to increase their own capacity. The committee

has referred to a number of bilateral education and training programs that are

effectively helping to build this capacity.

19.52

The committee also believes that PIF could become a more effective

regional mechanism for initiating and overseeing peacekeeping operations. Australia

should continue to encourage the forum to take on greater regional

responsibility in this area. As noted earlier, Australia is seeking to host the

2009 Pacific Islands Forum.

19.53

The committee is of the view that this level of engagement and support

is an important first step toward recognising and promoting the important role

that the forum has in regional affairs. The committee believes that, with

continued strong support from Australia, PIF could become an effective regional

mechanism for overseeing peacekeeping operations.

International engagement programs and future regional capacity

Australian initiatives in the

region

19.54

The Department of Defence contributes to regional capacity building

through its Defence Cooperation Program (DCP). The DCP aims to contribute to

regional security by encouraging and assisting with the development of the

defence self-reliance of regional countries. It also aims to promote more

effective and efficient security services consistent with the principles of

good governance.[47]

Defence advised:

Defence Cooperation Program activities encompass assistance to

regional security forces in the areas of strategic planning, education and

training, command and control, infrastructure, counter-terrorism,

communications and logistic support. The program also supports the conduct of

combined exercises to improve the ability of regional countries to contribute

to regional security. Training programs involve service personnel training

together in Australia and overseas, thereby contributing to increased levels of

mutual understanding and cooperation.[48]

19.55

The ADF and the AFP collaborate on delivering the DCP. They establish

distinct roles for security sector agencies, with an emphasis on the use of

police capability for internal security.[49]

19.56

The DCP's capacity-building activities have included combined exercises

with a number of Australia's regional partners. For example, the ADF and the

Papua New Guinea Defence Force (PNGDF) have been involved in a host of

activities including: professional military education for PNGDF personnel,

joint infrastructure projects and the preparation of PNGDF personnel for

deployment to RAMSI.[50]

19.57

While the Department of Defence Annual Report 2005–2006 devotes

numerous pages to the DCP, citing its activities in the South Pacific and South-East

Asia, the Annual Report 2006–2007 offers no such examples for this $80 million

(approx.) program.[51]

19.58

As noted in the previous chapter, another Defence initiative is the

training programs provided through the Asia Pacific Centre for Military Law

(APCML), University of Melbourne. Established in 2001, the centre runs a number

of training programs in subject areas such as peace operations and

international law, military operations law, military operations for commanders

and civil–military cooperation in military operations.[52]

Course participation in Australia is normally split evenly between ADF members

and regional military officers from South-East Asia and the South Pacific.

Defence anticipates expanding the number and type of courses available. The

centre promotes respect for the rule of law in peacekeeping and in military affairs

generally in both the ADF and the Asia–Pacific region.[53]

19.59

APCML also runs courses within the region. For example, it has conducted

a military ethics program for the Thai military which focused on legal issues

in military decision making. Members of other regional military organisations

also attended.[54]

19.60

In addition, APCML offers courses that appeal to non-military audiences

and engage presenters from non-military backgrounds. The centre's CIMIC courses

engage representatives from the NGOs, humanitarian sector and international

organisations.[55]

19.61

The committee notes that recently Australia has also sought to enhance

regional capacity in peacekeeping and peacebuilding through bilateral training

initiatives. In March 2007, then Prime Minister John Howard and Prime Minister Shinzo

Abe signed a Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation which will see Japanese

police train in Australia for peacekeeping operations.[56]

UN programs in the region

19.62

The committee received evidence suggesting that Australia could do more

to support UN training objectives in the region.[57]

Major General Ford outlined that the UN offers a number of training modules

for senior mission leaders. He also noted that no Australian had participated

in any of those courses and argued that potential future leaders should be

required to attend. He considered that there would be great value in

encouraging the UN to host one of the Senior Mission Leadership courses in the

Asia–Pacific region, facilitated by Australia:

It does not necessarily have to be here but perhaps we could

assist another country in hosting the course, much the same as we did with the

doctrine seminar that was run in Singapore earlier this year. I believe that we

need to get involved in helping the UN run these and other activities in the

region. That gives us a way of getting into those things. As a relatively rich

country I think we have a responsibility to do that.[58]

19.63

DFAT reported that three UN Senior Mission Leadership courses are

planned for 2008 in India, Australia and Brazil.[59]

Defence reported that it had not been approached to host a UN Senior Mission

Leadership course, but would discuss the feasibility of doing so through its UN

post in New York. Defence also commented that 'Given the multi-agency nature of

the course, the proposal would have to be examined in a whole-of-government

context'.[60]

19.64

The committee supports endeavours to host the course in Australia, or

elsewhere in the region, but suggests that DFAT ensure all relevant

stakeholders, including Defence, are aware of such plans. The committee also

encourages relevant agencies to pursue opportunities to place senior staff on

the course.

Global Peace Operations Initiative

19.65

Australian agencies participate in the United States Government Global

Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI), a program designed to address major gaps in

international support for peace operations.[61]

The GPOI program, scheduled to conclude in 2010, aims to build and maintain

capability, capacity, and effectiveness of peacekeeping operations. It aims to

achieve this through enhancing the ability of countries and regional and

sub-regional organisations to train, prepare for, plan, manage, conduct, and

learn from peace operations.[62]

DFAT commented:

Programmes such as the US's GPOI provide an opportunity for

enhancing our efforts to build the capacity of regional countries to respond to

conflict, disaster and instability though training and education. The capacity

of regional nations to undertake or contribute to peacekeeping is a critical

component of security in the Asia-Pacific region, and globally. In this context

Australia is promoting within the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) the

establishment of the peace operations network of expertise and the development

of ARF Civil Military Cooperation (CIMIC) Standard Operating Procedures.[63]

19.66

DFAT continued:

To ensure that efforts by the UN and regional organisations are

complementary, coordination between these bodies needs to be improved and this

can be promoted through GPOI-supported exercise and engagement activities. Australia

actively supports the objective of increasing the global capacity for peace

operations and the Department of Defence has committed an officer to work in

the US State Department to help enhance the effectiveness of GPOI in our

region.[64]

Committee view

19.67

The committee notes that the current Australian Government has sought to

strengthen Australia's engagement with the UN and has identified its membership

of the UN as one of the 'three pillars' of its foreign policy. It also

recognises the efforts that Australian government agencies have made to engage

with existing international initiatives to improve regional peacekeeping

capacity. The committee expects that agencies will continue their efforts in

developing regional cooperation for peacekeeping operations through bilateral

cooperation and regional fora such as the ARF. The committee believes that

Australian efforts to engage with global and regional organisations would be

facilitated by the establishment of a national peacekeeping institute.

19.68

As the most populous and largest economy in the southwest Pacific, Australia

shoulders a significant responsibility for peacekeeping operations in the region.

Given Australia's experience and resources, the committee believes that Australia

must move beyond existing bilateral initiatives to develop the region's

multilateral peacekeeping capacity. While the idea of a national peacekeeping

institute has been discussed in the context of training Australians for

peacekeeping, the committee also sees an important role for this proposed

institute in helping to build regional capacity. It could do so by opening up

courses or exercises to overseas participants. This matter is further discussed

in Chapter 25.

Part V

Safety and welfare of Australian personnel

In this part of the report, the committee looks at the

consideration given to the health and safety of Australian personnel deployed

on a peacekeeping operation, including the care and services available to

injured personnel. The committee's intention is to determine whether there are

lessons to be learnt from current practices and, if so, how they could be

improved. There are four chapters in this part of the report covering:

- measures taken during service to promote the health and safety of

Australian peacekeepers;

- post-deployment integration and health programs, including a

major section on mental health;

- the legislative framework governing the rehabilitation of, and

compensation for, those injured or disabled while serving in a peacekeeping

operation; and

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page