Alcohol Toll Reduction Bill 2007

THE INQUIRY

1.1

The Alcohol Toll Reduction Bill 2007 (the Bill) was introduced into the Senate

on 19 September 2007 by Senator Steve Fielding. On 14 February 2008 the Senate, on the recommendation of the Selection of Bills Committee, referred the Bill

to the Community Affairs Committee (the Committee) for inquiry and report by 18 June 2008.

1.2

The Committee received 96 submissions relating to the Bill and these are

listed at Appendix 1. The Committee considered the Bill at public hearings in Melbourne

on 6 May 2008 and Canberra on 15 May 2008. Details of the public hearings are

referred to in Appendix 2. The submissions and Hansard transcript of

evidence may be accessed through the Committee's website at https://www.aph.gov.au/senate_ca.

THE BILL

1.3

The purpose of the Bill is to create a culture of responsible drinking,

and to facilitate a reduction in the alcohol toll resulting from excessive

alcohol consumption.

1.4

The objects of the Bill are to:

- limit the times at which alcohol products are advertised on radio and

television for the protection of young people;

- provide for compulsory health information labels for alcohol products;

and

- provide for alcohol advertisements to be pre-approved by an Australian

Communications Media Authority Division containing experts from the health

industry, drug and alcohol support services and motor accident trauma support

services.

1.5

The Alcohol Toll Reduction Bill 2007 proposes a number of changes to the

way alcohol advertising is regulated in Australia, which are set out in

Schedule 1 of the Bill. The Bill provides that a broadcaster must not

broadcast, or authorise to be broadcast an alcohol advertisement otherwise than

as permitted by Schedule 1 of the Bill. The penalty for infringement is 1000

penalty units.

1.6

The Bill amends the Australian Communications and Media Authority Act

2005 to establish a Responsible Advertising of Alcohol Division within the

Australian Communication and Media Authority (ACMA) to approve the content of

alcohol advertisements broadcast and advise broadcasters on the standards and

control of alcohol advertising. Under the Bill the associate members chosen by

ACMA for the membership of the Division should represent the following groups:

the medical profession; the alcohol and drug support sector; motorist

associations and motor accident trauma support groups; and the alcohol retail

industry.

1.7

The Bill also amends the Broadcasting Services Act 1992 to

require ACMA to determine standards that are to be observed by commercial

television broadcasting licensees in relation to alcohol advertising. These

standards limit the times when advertisements for alcohol products can be

broadcast to 9pm to 5am each day of the week. The standards also provide for

the content of advertisements for alcohol products. Specifically they provide

that such advertisements not have strong or evident appeal to children and not

suggest that alcohol contributes to personal, business, social, sporting,

sexual or other success in life. The Bill voids a commercial television code of

practice which is not in accordance with the standards.

1.8

Finally the Bill amends the Food Standards Australia New

Zealand Act 1991 to provide that a standard be made for the

labelling of alcohol products and food containing alcohol. The standard would

provide for: the consumption guidelines of the National Health and Medical

Research Council; the unsafe use of alcohol; the impact of drinking on

populations vulnerable to alcohol; health advice about the medical side effects

of alcohol; and the manner in which the information may be provided (including

provision in text or pictorial form).

BACKGROUND

1.9

The issue of alcohol in Australia (including the advertising and

labelling of alcohol products) has been extensively considered in a number of different

forums in recent years. These include:

The New South

Wales Summit on Alcohol Abuse (2003);

The House of

Representatives, Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs, Road to

recovery: Report on the inquiry into substance abuse in Australian communities

(2003);

The National

Committee for the Review of Alcohol Advertising (NCRAA), Review of the

Self-Regulatory System for Alcohol Advertising: Report to the Ministerial

Council on Drug Strategy (2004); and

The Victorian

Parliamentary Drug and Crime Prevention Committee, Inquiry into Strategies

to Reduce Harmful Alcohol Consumption (2006).

1.10

In May 2006 the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy endorsed the

National Alcohol Strategy 2006 – 2009 with the goal to prevent and minimise

alcohol-related harm to individuals, families and communities in the context of

developing safer and healthy drinking cultures in Australia. To achieve this

goal, the Strategy has four aims:

- Reduce the incidence of intoxication among drinkers.

- Enhance public safety and amenity at times and in places where

alcohol is consumed.

- Improve health outcomes among all individuals and communities

affected by alcohol consumption.

- Facilitate safer and healthier drinking cultures by developing community

understanding about the special properties of alcohol and through regulation of

its availability.

1.11

The Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy also established a Monitoring

of Alcohol Advertising Committee (MAAC) with the role of undertaking continued

monitoring of alcohol advertising and the current regulatory system. The terms

of reference for the Committee include monitoring of the implementation and

impact of the current arrangements and regular reports to the Ministerial

Council. These reports are not publicly released. The members of MAAC are

Commonwealth and State public servants.

1.12

On 12 March 2008 the Senate, on the motion of Senator Andrew Murray,

supported a comprehensive inquiry into the need to significantly reduce alcohol

abuse in Australia and what the Commonwealth, States and Territories should

separately or jointly do with respect to a range of issues including pricing

and taxation, marketing, and regulating the distribution, availability and

consumption of alcohol. The comprehensive inquiry should be undertaken by a

parliamentary committee, an appropriate body or a specially established

taskforce.[1]

1.13

The policy approach to alcohol products in Australia has been recently

highlighted by government initiatives in relation to binge-drinking and the

health costs associated with alcohol. In March 2008, the Council of Australian

Governments (COAG) agreed to ask the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy to

report to COAG in December 2008 on options to reduce binge drinking including

in relation to closing hours, responsible service of alcohol, reckless

secondary supply and the alcohol content in ready to drink beverages.[2]

1.14

COAG also asked the Australia New Zealand Food Regulation Ministerial

Council to request Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) to consider

mandatory health warnings on packaged alcohol. On 2 May 2008 the Ministerial

Council requested FSANZ to 'consider mandatory health warnings on packaged

alcohol taking into account the work of the Ministerial Council on Drug

Strategy and any other relevant ministerial councils, any relevant guidelines

in New Zealand, the relevant recommendations from the soon to be released

National Health and Medical Research Council alcohol guidelines for low risk

drinking; and to consider the broader community and population-wide context of

the misuse of alcohol'.[3]

1.15

The Commonwealth Government's National Strategy on Binge Drinking, also

announced in March 2008 includes:

- $14.4 million to invest in sporting and community level

initiatives to confront the culture of binge drinking;

- $19.1 million to intervene earlier to assist young people and

ensure that they assume personal responsibility for their binge drinking;

- $20 million to fund advertising that confronts young people with

the costs and consequences of binge drinking;

- The establishment of a nationally consistent code of conduct on

alcohol use for peak sporting bodies and community sports organisations.[4]

1.16

In May 2008 the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy agreed to

fast-track the development of the National Binge Drinking Strategy. Ministers

will lead the development of an interim report to the July meeting of COAG

which will focus on:

- a national policy framework for Responsible Service of alcohol;

-

a preferred regulatory model to address secondary supply of alcohol

to minors;

-

options for reducing alcohol content in products including those

aimed at young people;

- possible standards and controls for alcohol advertising targeting

young people; and

- advice regarding the impact of health warnings on drinking

behaviours.[5]

1.17

The Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy also agreed to assess late

night lock-outs for licensed premises based on analysis across the nation of

existing and trial lockouts to recommend a preferred framework. This framework

will be used to effectively target police resources to binge drinking hot

spots.[6]

1.18

In April 2008 the Commonwealth Government announced the establishment of

a new National Preventative Health Taskforce to develop strategies to tackle

the health challenges caused by tobacco, alcohol and obesity and develop a

National Preventative Health Strategy by June 2009.[7]

1.19

Prior to the Budget, the Commonwealth Government also announced it would

increase the excise and the excise-equivalent customs duty rate applying to

'other excisable beverages not exceeding 10 per cent by volume of alcohol' from

$39.36 per litre of alcohol content to the full strength spirits rate of $66.67

per litre of alcohol content on and from 27 April 2008.[8]

This measure was prompted by concerns about binge-drinking (particularly by

younger people) of 'ready-to-drink' (RTD) beverages, also known as alcopops. On

15 May 2008 the Senate referred an inquiry dealing with ready-to-drink alcohol

beverages and the effect of the excise increase to the Community Affairs

Committee for report by 24 June 2008. Many of the issues and background to the

RTD inquiry overlap with this inquiry into the Alcohol Toll Reduction Bill.

1.20

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) is currently

reviewing the Australian Alcohol Guidelines: health risks and benefits

in collaboration with the Department of Health and Ageing. The draft revised

guidelines, now called the Australian alcohol guidelines for low-risk

drinking, were made available for public consultation in October 2007. These

draft guidelines are intended to give Australians guidelines on how to avoid,

or minimise, the harmful consequences of drinking alcohol including the

immediate effects of each drinking occasion and the longer-term effects of

regular drinking.[9]

1.21

The consumption advice in the draft guidelines differs from the previous

NHMRC guidelines from 2001. There is a simplified single guideline level for

alcohol intake for all adults which recommends two standard drinks a day or

less to minimise immediate and long-term risks of harm. There are also two

guidelines with special precautions for children and adolescents, and for women

who are pregnant, hoping to become pregnant, or breastfeeding.[10]

ALCOHOL IN AUSTRALIA

1.22

While the provisions of the Bill relate to advertising and labelling

issues, it is difficult to consider the merits of the Bill without also

considering the position of alcohol products in the community more generally.

Alcohol is the most widely used psychoactive, or mood-changing, recreational

drug in Australia. According to the 2007 National Drug Strategy Household

Survey 82.9% of the population aged 14 years and over had consumed at least one

full serve of alcohol in the last 12 months, while 9% of Australians drank

alcohol on a daily basis.[11]

1.1

The National Alcohol Strategy document notes that per capita

alcohol consumption in Australia is relatively high in comparison to many other

developed countries, ranked 34th out of 185 countries assessed by the World

Health Organisation. While there are difficulties in the availability of

reliable data on alcohol consumption in Australia, the available data indicates

that per capita alcohol consumption in Australia steadily declined from the

late 1980s until early 1990s when the consumption began to fluctuate.[12]

Figure 1:

Per capita alcohol consumption in Australia, various sources,

1989 to 2003.

Sources: World Health Organisation (WHO) 2005; Australian

Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2005; National Alcohol Indicators

Project (NAIP) 2003; World Advertising Research Centre (WARC) 2005.[13]

1.23

In Australia, alcohol is significant for many economic, social, health

and cultural reasons. Alcoholic products are enjoyed (largely responsibly) by

many millions of Australian adults. Alcohol producing companies create

employment for many thousands of people directly, as well as many more

indirectly in the areas of agriculture, distribution, retail, hospitality and

tourism. Alcohol industry sponsorship and sales contribute to numerous social,

cultural and sporting events and institutions. Taxes and excises on alcohol

products provide significant revenue to governments to reinvest in the

community. While there is scientific dispute, there is evidence to suggest

moderate consumption of alcohol may have positive health effects for some

people by, for example, contributing to the reduction of cardiovascular disease

risk.

1.24

However alcohol is also responsible for or associated with many negative

outcomes for society. These negative outcomes include: long term serious health

problems for heavy drinkers; fetal alcohol syndrome; sexual and domestic

violence; road accidents; and community disintegration (particularly in remote

and indigenous communities).

1.25

Recently released publicly-funded research by Professor David Collins

and Professor Helen Lapsley has estimated that the total social cost of alcohol

in Australia was $15.3 billion in 2004-05. This includes $1.6 billion in crime,

$3.6 billion in lost workplace production, $2.2 billion in road accidents and

$2.0 billion in health care costs.[14]

This made alcohol the second most costly abused drug in Australia after tobacco

($31.5 billion). Between 1992 and 2001 it is estimated that over 31,000

Australians died from alcohol caused disease and injury including liver

cirrhosis, road crash injury and suicide.[15]

In 2005-06 alcohol was the most common principal drug of concern reported in

closed treatment episodes (39%) tracked by the AIHW, and over half of all

treatment episodes included alcohol as a drug of concern.[16]

ALCOHOL ADVERTISING

The Current System

1.26

Under the current system for advertising alcohol products,

advertisements are subject to a number of different codes of practice. Of

particular importance are the Australian Association of National Advertisers

(AANA) Advertiser Code of Ethics which sets out general standards for all

advertisers and the Alcohol Beverages Advertising Code (ABAC) which sets out

additional standards for alcohol advertisers. Other applicable laws and codes

include: the Trade Practices Act; jurisdictional fair trading legislation; the

Commercial Television Industry Code of Practice; the Commercial Radio Code of

Practice; and the Outdoor Advertising Code of Ethics.

The Alcohol Beverages Advertising

Code (ABAC) Scheme

1.27

Australia has a quasi-regulatory system for alcohol advertising as

guidelines for advertising have been negotiated with government and consumer

complaints are handled separately but costs are borne by industry. The key

components of the Scheme are the Management Committee, the Alcohol Advertising

Pre-vetting System (AAPS) and the Alcohol Beverages Advertising Adjudication

Panel.

1.28

The ABAC Scheme Management Committee has five members. One from each of

the major industry associations: the Australasian Brewers Association; the

Distilled Spirits Industry Council of Australia; and the Winemakers Federation

of Australia. The other two members represent the Advertising Federation of

Australia and the Department of Health and Ageing.

1.29

The ABAC Scheme Management Committee appoints the 'pre-vetters' for the

Alcohol Advertising Pre-vetting System (AAPS). Alcohol beverage advertisers can

use the AAPS pre-vetting service to assess whether proposed advertisements

conform to the Australian Association of National Advertisers Code of Ethics

(AANA) or the Alcohol Beverages Advertising Code (ABAC) before they are released

publicly. The AAPS is funded on a user-pays basis by those industry members

seeking pre-vetting of advertisements.

1.30

The ABAC Scheme Management Committee also appoints the members the Alcohol

Beverages Advertising Adjudication Panel. The Adjudication Panel adjudicates

complaints made concerning advertisements for alcohol beverages which are made

to the Advertising Standards Board established by the AANA and referred to the Adjudication

Panel for adjudication. The Management Committee must appoint a health sector

representative as one of the three regular members of the Panel. This person is

chosen from a shortlist of three candidates provided by the Minister for Health

and Ageing. Signatories to the ABAC Scheme are required to abide by the

provision of the Code, the associated rules and procedures and decisions made

by the Adjudication Panel. The costs of the Adjudication Panel are met by the

three industry associations.

1.31

No person appointed to the Adjudication Panel or the AAPS pre-vetters

may be a current employee or member of the alcohol beverages industry or have

been in the five years prior to their appointment.

1.32

The Alcohol Beverages Advertising Code is set out at Appendix 3. In

summary, the Code requires that alcohol advertisements:

- must not encourage excessive alcohol consumption or abuse of alcohol;

- must not encourage under-age drinking;

- must not have a strong or evident appeal to children (there are specific

rules relating to the inclusion of children in advertisements);

- must not suggest that alcohol can contribute to personal,

business, social, sporting, sexual or other success;

-

must not depict alcohol consumption in relation to the operation

of machinery or vehicles;

- must not challenge or dare people to consume alcohol;

- must not promote a beverage on the basis of its higher alcohol content;

and

-

must not encourage consumption that is in excess of the NHMRC Australian

Alcohol Guidelines.

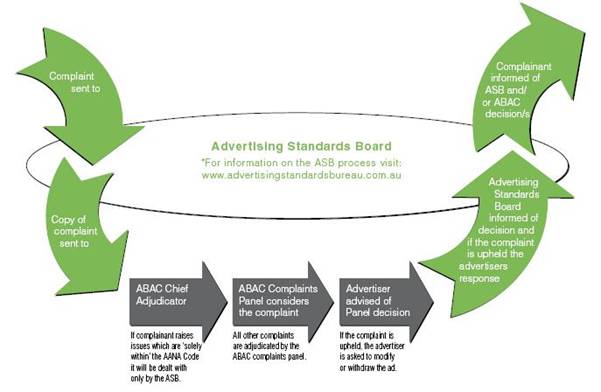

Figure 2: The ABAC Complaints Management System[17]

Commercial Television Industry Code

of Practice and the Commercial Radio Code of Practice

1.33

The content of free-to-air commercial television is regulated by the

Commercial Television Industry Code of Practice (CTICP) which has been

developed by FreeTV Australia and registered with the Australian Communications

and Media Authority (ACMA). The Code covers the matters prescribed in section

123 of the Broadcasting Services Act and other matters relating

to program content that are of concern to the community including: program

classifications; accuracy, fairness and respect for privacy in news and current

affairs; advertising time on television; and placement of commercials and

program promotions and complaints handling.

1.34

Under the CTICP a commercial which is a 'direct advertisement for

alcoholic drinks' may be broadcast only in M, MA or AV classification periods;

or as an accompaniment to the live broadcast of a sporting event on weekends

and public holidays; or where the event is simulcast to a number of licence

areas and a direct advertisement for alcohol is permitted in the area where the

event is held. The CTICP also provides that advertisements to children must not

be for, or relate in any way to, alcoholic drinks or draw any association with

companies that supply alcoholic drinks (Clause 2.9).

1.35

M classification periods are from 8.30 pm to 5.00 am, plus 12.00 noon to 3.00pm on weekdays (excluding school holidays). The MA classification zone

covers every day between 9.00pm and 5.00am. In MA zones, any material which

qualifies for a television classification may be broadcast, except material

classified AV which may only be broadcast after 9.30pm. The exemption for live

sport, for weekends and public holidays allows alcohol advertising as an

accompaniment to a 'live' sporting broadcast, shown at any time of day.

1.36

The Commercial Radio Code of Practice does not set out restrictions as

to the timing of alcohol advertisements but 1.3 (c) of the Code provides that a

commercial radio licensee must not broadcast a program which presents as

desirable the misuse of alcoholic liquor.

1.37

Under the co-regulatory arrangements set out by the Broadcasting

Services Act 1992 audience complaints regarding the CTICP or the Commercial

Radio Code of Practice can be made directly to the broadcaster who must reply

within 30 days and inform the complainant of their right to refer their

complaint to ACMA for investigation. ACMA can apply penalties to broadcasters

for breaches of industry codes of practice.

Specific to children

1.38

Specific protections also exist in relation to children and alcohol

advertising. The Children's Television Standard made by ACMA under the Broadcasting

Services Act 1992 also restricts the times when alcohol advertising can be

broadcast on television. Complaints about advertising perceived to conflict

with the Children’s Television Standard can also be made directly to the ACMA

who can then investigate. The AANA also recently released a Code for

Advertising to Children which provides that:

2.9.1 Advertisements to Children must not be for, or relate in

any way to, alcoholic drinks or draw any association with companies that supply

alcoholic drinks.

Responsible Advertising of Alcohol

Division

1.39

As outlined earlier, the Bill establishes a Responsible Advertising of

Alcohol Division within ACMA to pre-approve alcohol advertisements and provides

for its membership.

1.40

A number of submissions which supported the creation of the Division suggested

alternatives or additions to the membership of the Division. For example the

Public Health Association of Australia suggested the Bill be amended to include

'one associate member representing the public health sector'.[18]

Dr Susan Dann suggested that the proposed Division needed 'expertise from the

marketing and advertising professions' with 'expert knowledge in terms of how

different communications strategies and marketing approaches are likely to

impact on the consumer behaviour of different target markets'.[19]

The Anglicare Victoria and Melbourne Anglican Social Responsibilities Committee

suggested that representatives of the alcohol suppliers industry and their

advertisers also be included in the Division’s membership.[20]

Professor Sandra Jones recommended the pre-approval body 'include a communications

expert and a youth studies expert, or other appropriate representative of young

Australians' and also that the process include a mechanism to take into account

community perceptions which are likely to change over time.[21]

1.41

The Australian Christian Lobby supported the Bill but noted that the

Australian Communications and Media Authority 'causes concerns to many family

organisations... [as] the policing of television standards has been too lax, its

complaint processes are slow, and its judgements fail to constrain the

behaviour of broadcasters'. This concern regarding the role of ACMA was shared

by the Festival of Light which noted that 'ACMA is notoriously slow in dealing

with complaints'. They also suggested there should be 'an efficient complaints

mechanism for members of the public to complain that despite ACMA approval a

particular advertisement breaches the standard'.[22]

1.42

The alcohol industry raised concerns about the proposed Division. The

Distilled Spirits Industry Council of Australia was concerned about the lack of

balance in the Division's membership and the lack of clarity as to how the

Division would reach decisions. It suggested 'representation of the alcohol

industry would be more appropriate by an alcohol manufacturer, rather than a

retailer' and also expressed concern the Division will not have a

representative to balance out practice concerns of the advertising industry.[23]

Dual systems

1.43

A number of submitters were concerned the Bill was replacing the current

ABAC Scheme with a less comprehensive system of regulation. However Senator Fielding,

who introduced the Bill, noted that the intention of the legislation was that

the measures introduced by the Bill would add to and not replace the existing

self-regulation measures set up under the ABAC Scheme.[24]

1.44

Some submissions did not see benefit in a dual system of regulation for

alcohol advertising. The Advertising Federation of Australia characterised the

proposed Division as creating 'an unwieldy duplication of regulatory function.[25]

Similarly the Foundation for Advertising Research stated:

An added complication is that a Government agency would become involved

in a highly competitive industry where confidentiality is paramount. This is

not an appropriate role for ACMA, as a key stakeholder to be involved in

administrative functions.[26]

1.45

The Distilled Spirits Industry Council argued that the pre-approval role

would impose 'severe practical difficulties on the both advertising and alcohol

industry'. It suggested that timeframes for advertisement development and

production would be lengthened adding to costs; confidentiality would be

weakened; the lack of a timely pre-vetting system would restrict creativity;

and the government regulation would politicise alcohol advertising.[27]

FreeTV Australia also noted that regulating alcohol advertisements through ACMA

could be a much more inefficient process and ACMA would need to be extensively

funded and resourced to fulfil the new role.[28]

Discussion of the ABAC Scheme

1.46

Many of the assessments regarding the merits of establishing the proposed

Responsible Advertising of Alcohol Division concerned the effectiveness of the

existing ABAC Scheme.

Self regulation

1.47

A number of criticisms of the ABAC Scheme were raised regarding a

perceived inherent conflict of interest in the alcohol industry regulating

advertising for alcohol products. Dr Alex Wodak described self-regulated

alcohol promotion and advertising as a 'farce', noting that the alcohol beverage

industry 'decides the rules, appoints the judge and jury and then runs the system'.[29]

The Australian Christian Lobby characterised self regulation of alcohol

advertising as a 'demonstrable failure' and likened it to leaving 'Dracula in

charge of the blood bank'.[30]

Mr Paul Mason the Tasmanian Commissioner of Children stated there was 'an

inherent conflict in an industry which seeks to portray itself as reducing the

consumption of alcohol while depending for its sales on the increased

consumption of alcohol'.[31]

1.48

Professor Sandra Jones described her research of alcohol advertising

regulation, from 1998-99 to her most recently published study in January 2008.

Her research examined the extent that decisions made by the Advertising

Standards Board and Adjudication Panel were consistent with young people's

perceptions of the messages in alcohol advertisements and also expert academic

judgements on whether alcohol advertisements breached industry codes. Professor

Jones characterised these results as consistent despite reforms to the ABAC

Scheme over the years stating '[e]ach time there is review of the system, we do

another study and find that the system does not work'.[32]

1.49

The Salvation Army argued that 'the current self-regulatory approach is

not meeting the challenge of protecting the public, particularly young people,

from the inappropriate and misleading messages and associations between alcohol

and lifestyle and life outcomes'.[33]

Similarly the Alcohol Education and Rehabilitation Foundation stated that

studies in Australia and overseas have shown that voluntary codes of

advertising are an ineffective method of regulating advertising content. They

believed that re-regulation of alcohol advertising would enable more effective

enforcement of an advertising code.[34]

1.50

However the ABAC Scheme was defended by advertisers, broadcasters and

the alcohol industry associations. For example, the Australasian Associated

Brewers (AAB) rejected arguments that the ABAC Scheme was a form of industry

self-regulation of alcohol advertising, arguing it was a quasi-regulatory

system ie, one that was a result of government influence on business. They

noted that the ABAC Scheme had been negotiated with the government and that a

government representative was on the ABAC Scheme Management Committee. The AAB

highlighted that the members of the Management Committee were not advertisers

and did not play a role in assessing any advertisement against the standards

set out in the Code.[35]

1.51

In particular the alcohol industry association stressed the independence

of the AAPS pre-vetters and the Adjudication Panel in applying the provisions

of the Code. The Distilled Spirits Industry Council of Australia noted that

following negotiations, two of the five members of the panel are nominated by

the Commonwealth through the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy. Furthermore

each complaint must be dealt with by three panel members and one must have a

public health background and be nominated through the Ministerial Council.[36]

1.52

The independence of the ABAC Adjudication Panel and the AAPS from the

Management Committee was supported by Professor Michael Lavarch, the Chief ABAC

Adjudicator and Ms Victoria Rubensohn, the Pre-vetting Adjudicator. Professor Lavarch

stated:

I can also say from my experience that there has never been an

occasion, not once, when I have had any direction, influence or suggestion from

the management committee on the decision-making process in relation to looking

at a particular complaint in a particular ad. That has never happened. Speaking

from the complaint side, I believe that it is an independent process from the

industry.[37]

1.53

Australian Association of National Advertisers highlighted that the separate

adjudication under ABAC and AANA Codes meant that alcoholic products

advertising in Australia is subject to ‘double jeopardy’ in needing to meet two

sets of standards designed to protect the broadest community interests.[38]

1.54

FreeTV Australia highlighted the consistently low level of audience

complaints in relation to alcohol advertising, stating there was 'very little

evidence of community dissatisfaction' with alcohol advertising.[39]

The Advertising Standards Bureau also noted that the number of complaints

submitted to the ASB regarding alcohol advertising is at a five year low and

have trended down over recent years.

The most recent statistics of complaints relating to alcohol

show that in 2007 alcohol advertising attracted 2.44% of complaints, while the

percentage of complaints in the previous four years were respectively 3.14%,

7.07%, 21.38%, and 11.6%.[40]

1.55

The ASB contended the current system met the 'gold standard' of

regulation as set out by the World Federation of Advertisers. These criteria

were:

- Universality (covering all advertising and backed by advertisers/agencies

and media)

- Sustained and effective funding

- Efficient and resourced administration

- Universal and effective codes

- Advice and information

- Prompt and efficient complaint handling

- Independent and impartial adjudication

- Effective sanctions

- Efficient compliance and monitoring

- Effective industry and consumer awareness.[41]

1.56

The Foundation for Advertising Research acknowledged the ABAC Scheme

possibly needed improvement in the areas of independent monitoring and audit

but argued the 'the best way forward is to ensure it meets best practice

principles rather than throwing the baby out with the bath water'.[42]

Compliance

1.57

Another area of criticism of the ABAC Scheme was in relation to

compliance. Professor Sandra Jones highlighted the lack of consequences for advertisers

when they are found to have breached the Code. She argued that where the ABAC

finds a breach, 'all that happens is that they ask the advertiser to withdraw

it' and that there should be a penalty for advertiser or manufacturers who

breach the Code.[43]

VicHealth also highlighted that Adjudication Panel decisions are not

enforceable and described this as a significant weakness in compliance under

the ABAC Scheme.[44]

1.58

Professor Michael Lavarch acknowledged that the ABAC Adjudication panel

did not have any power to sanction advertisers which breached the Code. However

he noted:

Any self regulatory system has, at its heart, the commitment of

the participants of the system to comply with it. That is the nature of a

self-regulatory system.[45]

1.59

Mr Dominic Nolan, the Winemakers Federation of Australia member of the

ABAC Management Committee, argued that the consequences of having an

advertisement withdrawn encouraged compliance by advertisers. He stated:

...it is in the interests of the members of the alcohol industry to

run their ads through the pre-vetting system, because if they run an

advertising campaign, there is a complaint, it is upheld and they have to

withdraw the campaign, then there are major financial repercussions; it does

cost those people a significant amount of money. There are examples where ads

were approved under the pre-vetting system, there was a complaint made and

upheld, and the ad was subsequently immediately withdrawn, and it did cost the

companies involved a very large amount of money, which demonstrates the efficacy

of the scheme in place.[46]

Audience awareness

1.60

VicHealth highlighted recent research which indicated 'very limited

public awareness and confidence in the ABAC scheme'. The research estimated

that only 3 per cent of the total adult population are aware of the

existing ABAC scheme and know what it relates to. Most people surveyed did not

know how to make an effective complaint and the few people who had complained

were not satisfied with the result.[47]

1.61

The alcohol industry did not consider that high public awareness was

critical to the success of the ABAC Scheme. Mr Dominic Nolan stated:

I think the important thing is that, if someone has a concern

and wishes to raise a complaint about anything to do with an alcohol

advertisement that they see, they should be able to easily find out how they

can do that. The number of avenues available for that to occur through the

internet, through the ASB and through the relevant television stations clearly

demonstrates that anyone who was searching for a way to make a complaint could

very easily find one. Whether or not they are specifically aware of the ABAC

scheme or otherwise I do not think is particularly relevant, given that that

complaint can always be made and that people can always find out information if

they are so motivated.[48]

Limiting Alcohol Advertising Times

Advertising and Sport

1.62

The Bill aims to limit the broadcasting of television and radio alcohol advertisements

to the period 9pm and 5am each day. Professor Sandra Jones noted that the primary

impact of this would be to 'remove the current anomaly which allows alcohol

advertising during live sporting telecasts, which is a big problem in this

country'. She stated:

Our research and the research of others clearly shows that

children have a very high awareness of and liking for alcohol brands,

particularly due to their exposure to them during sporting telecasts and the

links that those children make between those products, their sporting heroes

and the codes.[49]

1.63

Mr Todd Harper of VicHealth also described current regulations allowing

alcohol advertising during sports as an 'anomaly' inconsistent with the broader

goals of harm reduction and the spirit of the frameworks which seek to limit

alcohol advertising exposure to children.[50]

Similarly Mr Geoffrey Munro of the Australian Drug Foundation told the

Committee:

No-one is challenging the need for alcohol advertising not to be

shown during children’s viewing hours. That restriction is placed there

deliberately to protect children from alcohol advertising. It makes no sense at

all to allow that advertising restriction to be undermined when alcohol brands

sponsor sport, which is televised and which means that promotions and

advertising of alcohol brands can be shown from 9 am or earlier right through

the day. It makes no sense at all. We do not understand why that loophole

exists.[51]

1.64

The Bendigo Community Health Services highlighted a number of benefits

in restricting television advertising between 9 pm and 5 am. These included: reducing the impact of visual reinforcement; reducing the number of young

people viewing alcohol advertisements; reducing the sensationalising of alcohol

to young people and reducing the message that alcohol is a form of

entertainment.[52]

1.65

The Australian Christian Lobby argued that despite ABAC provisions to

the contrary, alcohol is often linked with sporting success. It noted:

Alcohol manufacturers are prominent sponsors of sporting

contests, which are usually screened throughout the day, meaning that such

advertisements are inevitably seen by children and the use of celebrities,

humour and mascots often appeals to them. This is all the more disturbing as the

people featured in such ads are often sports stars, who children may seek to

emulate.[53]

1.66

Sporting organisations raised concerns about limiting alcohol

advertising during sports coverage. The Australian Sports Commission indicated

that many sports, particularly professional codes receive a large proportion of

their income from alcoholic beverage sponsorship agreements or associated

income. It estimated that sponsorship of sporting events in Australia is worth

approximately $1.25 billion per year and alcohol companies are represented

among the top 40 sport sponsors. The Commission suggested that if the Bill was

passed there would 'need to be a phasing in period that would allow sports the

opportunity to attempt to seek alternative revenue streams'. [54]

1.67

The Coalition of Major Professional Sports stated:

The hours of the proposed restriction on alcohol advertising

have a strong overlap with the television and radio broadcasting coverage of

all of the major professional sports – as much as 100% overlap of airtime in some

instances. The professional sports business model in Australia is heavily

underpinned by investment in the media rights of sports by free-to-air and pay

television broadcasters. The business model of free-to-air broadcasters is

almost exclusively reliant on advertising and restrictions such as those

proposed in this Bill have the potential to significantly reduce advertising

income derived from alcohol producers. This has the potential to lead to a

reduction in the rights fees payable by broadcasters to some sporting

organisations, thus there is a possibility of compromising the primary

commercial driver in modern professional sporting business models.[55]

1.68

The Confederation of Australian Sports argued that sport has the

potential to provide strong leadership in the area of responsible alcohol

management and public education. It highlighted the involvement of many

sporting clubs with the 'Good Sports' program organised with the Australian

Drug Foundation. It argued that the measures in the Bill could result in

significant financial cost to sporting clubs and associations and this may be 'counter

productive as the financial cost to sport may affect its capacity to

effectively implement programs that work to change the culture of drinking across

the country'.[56]

1.69

However it was noted in a number of submissions that tobacco had

successfully been phased out of sports advertising and sponsorship. Professor Sandra

Jones commented:

If you watch the tennis, for example, you almost never see an

alcohol advertisement because they are sponsored by things like shampoo

companies, razor companies. There will be other sponsors out there. It would

need to be carefully managed to make sure it did not have a major impact on

sporting codes and some sort of funding would need to be provided while that

transition is occurring.[57]

Advertising and consumption

1.70

The Committee received conflicting evidence regarding the link between

the advertising of alcohol products and harmful consumption of alcohol,

particularly by children and young people. This was seen as an important issue

in consideration of the Bill as the measures to reduce the harms associated

with alcohol consumption by restricting advertising assumes a link exists.

1.71

Submissions from alcohol industry groups, advertisers and broadcasters

argued that there should be clear evidence that alcohol advertising is

contributing to the misuse of alcohol before the current regulatory scheme is changed.

The Distilled Spirits Industry Council of Australia argued that alcohol

companies advertise in order to increase market share and influence consumer

choice towards products with higher margins rather than to increase overall consumption

of alcoholic products. They provided information indicating that despite a

large increase in the amount of advertising expenditure in Australia, the

overall levels of alcohol consumption have remained relatively stable over the

past decade.[58]

1.72

Ms Flynn of FreeTV Australia also noted that a range of advertisements

may attract the attention of children but that 'exposure' does not mean the

advertisement is targeted to children or that, even if a child remembers an

advertisement he or she is necessarily interested in the product being sold.[59]

Similarly Ms Joan Warner of Commercial Radio Australia believed 'there is no

evidence of a causal effect linking responsible radio advertising with

irresponsible drinking patterns among the young'.[60]

1.73

Australian Association of National Advertisers referenced research by

Frontier Economics which suggested 'in a wide range of studies ...notably on

alcohol ads ... (advertising bans) are ineffective in reducing harmful

consumption and may even have perverse effects.' This research cited studies

that suggest little evidence of a significant link between advertising and

total sales of alcoholic drinks, or consumption per head or 'where a positive

link has been found, it tended to be very slight'. The AANA also indicated that

bans or restrictions on advertising alcohol had the potential for unintended or

even perverse consequences such as driving advertising into less regulated

media.[61]

1.74

However Professor Sandra Jones told the Committee there is 'clear

evidence from both experimental studies and longitudinal research, exposure to

alcohol advertising is clearly associated with drinking intentions and drinking

behaviours among young people'.[62]

She described recent longitudinal studies from the United States which 'conclusively

show that there is a very, very strong link with exposure to adverting and

drinking' and have found a strong association between the amount of alcohol

advertising and marketing children are exposed to and the age they commence

drinking and how much alcohol they consume.[63]

1.75

Similarly the Festival of Light emphasised a recent review of seven

international research studies which concluded:

The data from these studies suggest that exposure to alcohol

advertising in young people influences their subsequent drinking behaviour. The

effect was consistent across studies, a temporal relationship between exposure

and drinking initiation was shown, and a dose response between amount of

exposure and frequency of drinking was demonstrated.[64]

1.76

The Committee notes that the Victorian Parliamentary Drugs and Crime

Prevention Committee examined this issue in detail during the Inquiry into

Strategies to Reduce Harmful Alcohol Consumption in 2006. It concluded:

The Committee acknowledges that the issues and debates

pertaining to alcohol advertising and its regulation are complex ones.

Notwithstanding the highly persuasive sources and arguments in favour of

stricter (statutory) interventions, the Committee believes any firm links

between alcohol advertising and increased or harmful alcohol consumption

(particularly among young people) remain inconclusive.[65]

Advertising Standards

1.77

The Bill requires ACMA to determine standards to be observed by

commercial television broadcast licensees which provide that the content of any

advertisement for an alcohol product must not have strong or evident appeal to

children and not suggest that alcohol contributes to personal, business,

social, sporting sexual or other success in life. These terms appear to have

been modelled on part of the ABAC Code. A number of submissions supported these

provisions of the Bill as they believed the AAPS and the Adjudication Panel had

not applied these standards effectively.

1.78

The Australian Christian Lobby noted that advertisements 'aimed at children

or which link drinking or personal, business, social, sporting, sexual or other

success are supposedly already banned by the Alcohol Beverage Advertising Code'.

They argued that since the ABAC Scheme had not been successful in preventing infringing

advertisements 'it is time for a legislative ban as proposed in this bill'.[66]

1.79

Mr Brian Vandenberg outlined VicHealth's concerns that it had been very

difficult for the ABAC Adjudications to adhere to the Code as terms such as 'promoting

sexual or social success' were ambiguous and not defined.[67]

The South Australian Government also noted that 'the interpretive nature of the

Code has meant that in some cases advertisements that passed the pre-vetting

process were later the subject of a complaint upheld through the complaints

process'.[68]

1.80

The Australian Drug Foundation argued that crucial concepts of the

Code are not defined (eg. sexual success or offensive behaviour) so there is

not a clear guide for the Adjudication Panel to determine whether an

advertisement does breach the code. They argued the Panel had used a black

letter approach to the Code and 'has interpreted advertisements most literally

although advertising evokes and conveys meaning through allusion and inference

rather than linear logic'. [69]

They suggested that 'practice guidelines' be provided to guide the ABAC

pre-vetters and the Adjudication Panel as to the interpretation of the Code.[70]

1.81

The ABAC Management Committee have developed Guidance Notes to assist

advertisers, agencies and decision makers under the ABAC Scheme including the AAPS

pre-vetters and the Panel Adjudicators in interpreting the essential meaning

and intent of the ABAC by providing clarifications through definition,

explanations, or examples.[71]

1.82

Professor Lavarch, the Chief Adjudicator, gave evidence to the Committee

that advertisements which come to the Adjudication Panel via a complaint are

generally ones which two reasonable people 'looking at the ad—who are trying to

apply it against the code, against the backdrop of community standards, and who

have an understanding of the public policy considerations of why we are

concerned about alcohol regulation and advertising—might come to different

conclusions about'.[72]

Scope of the legislation

1.83

A concern repeatedly raised in submissions was that the scope of the Bill

should be expanded from television and radio advertising, and should form part

of a comprehensive approach to address the harms caused by alcohol. Many

submissions noted that alcohol advertising occurs via a number of media rather

than just through television and radio such as posters, magazines, newspapers,

internet, mobile phone SMS social marketing and promotional offers and events. The

National Centre for Education and Training on Addiction commented that 'the

largest part of a company's marketing budget is often invested into other

promotional activities...'[73]

1.84

FreeTV Australia stated that when beverage and retail advertising of

alcohol products is considered, television advertising accounts for less than

25% of all annual advertising expenditure.[74]

Commercial Radio Australia estimated only 5% of all annual advertising

expenditure is via radio and highlighted that it did not broadcast children's

programming.

1.85

FreeTV Australia argued for a media neutral approach to alcohol

advertising:

Any proposed regulatory action to address alcohol advertising

must take a consistent approach across media platforms, and not unduly focus on

free-to-air television. Experience shows that if advertising is restricted on

one platform, the advertising expenditure redistributes to other, competing

media. There would therefore be no overall reduction in alcohol advertising.[75]

1.86

The Foundation for Advertising Research also argued that the best

practice approach was for advertising restrictions to apply to all media to

ensure 'a level playing field'. Otherwise ' advertising will migrate to other

media with no reduction in the total amount of advertising'.[76]

Similarly the Advertising Federation of Australia argued the Bill 'will do nothing

more than swill advertising spend necessarily away from those media into other

channels that are not restricted in the same way' and that 'marketing spend on

alcohol would remain the same, but radio and television spend would form a

smaller percentage of the overall investment in alcohol advertising'.[77]

1.87

Dr Alex Wodak questioned the priority given to regulating alcohol

advertisements in the Bill compared to other strategies to address the harms

caused by risky alcohol consumption. He highlighted the effectiveness of other

policy approaches such as raising the price of alcohol products via taxation

and restricting availability. He noted:

At best, restricting alcohol advertising

and ending self regulation should be regarded as supportive but not primary

strategies.[78]

Labelling

The current system

1.88

Part 2.7 of the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code (the Food

Standards Code) provides specific labelling requirements for alcoholic

beverages and food containing alcohol. Part 2.7 also sets out definitions of

beer, fruit and vegetable wine, wine and wine products and spirits. Part 2.7 requires

a declaration of alcohol by volume and 'standard drink' labelling and sets out

labelling rules for representations of 'low alcohol' and ‘non-intoxicating' and

provides that food containing alcohol not to be represented as non-alcoholic.

1.89

In general, under the Food Standards Code the label on a package of food

or a beverage must include a nutrition information panel in the following

format (unless otherwise prescribed under the Code).

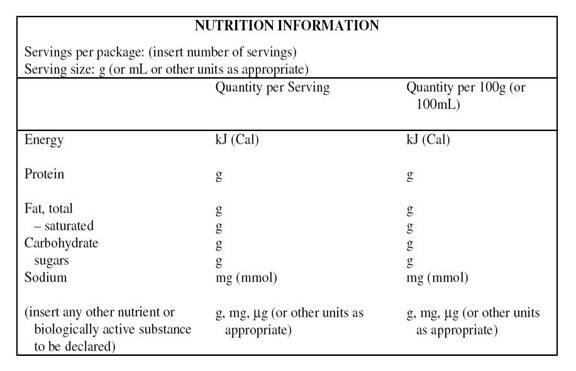

Figure 3:

Nutrition information panel

1.90

However the Standard 1.2.8 of the Code makes an exemption for alcoholic

beverages standardised in Standard 2.7 from being required to display a nutrition

information panel. A number of other foods and beverages are also exempted from

the nutrition label requirements, often where they are standardised in other

parts of the Code, including vinegar, tea, coffee, prepared filled rolls, where

items they are sold at fund-raising events, or where they are in small

packages.

1.91

In 2000, the then Australian New Zealand Food Authority (ANZFA) rejected

an application from the Society Without Alcohol Trauma to amend the Food Standards

Code to include a requirement that all alcoholic beverages be labelled with the

statement: This product contains alcohol. Alcohol is a dangerous drug.

1.92

In the statement of reasons for the rejection of the application the

ANZFA noted that the costs associated with alcohol were high, but stated:

Scientific evidence for the effectiveness of warning statements

on alcoholic beverages shows that while warning labels may increase awareness,

the increased awareness does not necessarily lead to the desired behavioural

changes in ‘at-risk’ groups. In fact, there is considerable scientific evidence

that warnings statements may result in an increase in the undesirable behaviour

in ‘at risk’ groups.

In the case of alcoholic beverages, simple, accurate warning

statements, which would effectively inform consumers about alcohol-related

harm, would be difficult to devise given the complexity of issues surrounding

alcohol use and misuse, and the known benefits of moderate alcohol consumption.[79]

1.93

ANZFA also noted that while the costs to industry of labelling alcoholic

beverages with warning statements was not expected to be high, the scientific

evidence did not show that warning statements were effective in modifying at

risk behaviour in relation to consuming excessive amounts of alcohol. It noted

the other public health and education initiatives already in place and the trend

of decreasing alcohol consumption and decreasing alcohol-related costs and harm

in Australia and New Zealand. In terms of regulatory impact, ANZFA concluded

that requiring labelling of alcoholic beverages with warning statements 'would

offer no clear benefits to government, industry and consumers but would

introduce costs to government, industry and consumers'.[80]

Label content

1.94

While a number of countries mandate warning labels on alcohol products, there

is no international consensus or specific Codex standards on the use of warning

labels on alcoholic beverages nor consistency of format and/or wording.[81]

Since 1989, all alcoholic beverage containers sold or distributed in the United

States have been required to bear the following statement:

GOVERNMENT WARNING: (1) According to the Surgeon General, women

should not drink alcoholic beverages during pregnancy because of the risk of

birth defects.

(2) Consumption of alcoholic beverages impairs your ability to

drive a car or operate machinery, and may cause health problems.

1.95

The Bill requires FSANZ to make a standard for labelling alcohol products

which would include the NHMRC guidelines on the unsafe use of alcohol; the

impact of drinking on populations vulnerable to alcohol; health advice about

the medical side effects of alcohol; and the manner in which the information

may be provided (including provision in text or pictorial form).

1.96

The labelling provisions received significant support in a number of

submissions. For example the Alcohol Tobacco and Other Drugs Council of

Tasmania Inc stated 'appropriate labelling can only improve consumers'

awareness of safe drinking limits, the risks of excessive use, and help

vulnerable people to avoid harm'.[82]

Other submissions supported the addition of labels to alcohol products but made

suggestions as to the best method of implementation.

1.97

VicHealth recommended that the revised NHMRC guidelines for low-risk

drinking should be the basis for the messages in the health information labels;

that the labels should be both textual and graphic for ease of comprehension;

and there should be strict guidelines on the wording, format and legibility

standards relating to health information labels.[83]

1.98

While Professor Sandra Jones supported the components of the Bill

related to health information labels, she also noted the need for research into

what the content and format of those labels should be. She argued that labels

should be tailored to target relevant audiences and gave the example of

'labelling alcopop beverages with warnings about issues associated with the

harms of binge-drinking' rather than other long-term health effects of

consumption.[84]

1.99

Industry groups objected to the proposed changes to labelling. The

Distilled Spirits Industry Council of Australia described the measure as

'difficult to implement and in some cases unfeasible'. They argued that the

size and complexity of the current NHMRC guidelines precluded their use on

alcohol product labels and that the labelling requirements would impose a

'significant and recurring cost' on the industry.[85]

Similarly the Winemakers Federation of Australia argued:

To include all of the above information is impractical or

impossible and would require a label of considerable size and detail, making it

unworkable for most packaging and ineffective in delivering a simple and

accurate message for consumers.[86]

1.100

The Northern Territory Government considered it debatable whether labels

on alcohol products should be based on the NHMRC safe drinking guidelines. They

commented:

This arises from factors such as the changing nature of the

guidelines, the complexities associated with individual differences, the

balancing of benefits and risks, the distinctions between long-term and

short-term harms, and the relevance to different sub-groups of drinkers. It

would be better to have more targeted approaches to the information generated

by the NH&MRC so it can be delivered in more meaningful and engaging ways.[87]

1.101

The Anglicare Victoria and Melbourne Anglican Social Responsibilities

Committee raised their concern that the proposal for health warning labels on

alcohol products contain information regarding 'the impact of drinking on

populations vulnerable to alcohol' could inappropriately stigmatise or

disproportionately target Australia’s Indigenous communities.[88]

1.102

A number of submissions argued that adding additional information or

warning labels to alcohol products would assist consumers to make informed

choices. For example the Network of Alcohol and Drug Agencies argued that

labels provided a way for consumers to be informed at the 'point-of-drinking'

that the product they are consuming can have a serious impact on their health

and well-being.[89]

1.103

The Australian Drug Foundation noted that adding labels to alcohol

products does not interfere with a person's right to drink. They stated:

We see it as a basic consumer right to health information. We

also see labels as being very important in reinforcing messages delivered

through other mediums such as the media, schools, community education et

cetera. We see labels as a very important way to educate the consumer, and the

best time to do that is as they are consuming the product.[90]

1.104

Several submissions also noted that Australian alcohol prepared for

export often already includes a health warning label. Mr Scott Wilson of the

Alcohol Education and Rehabilitation Foundation stated:

In 2008 I cannot understand why Australian consumers do not have

the same rights as consumers of Australian alcoholic products that are exported

right around the world. For example, if you are in the US, Canada, the UK or

Europe and you pick up a bottle of Jacob’s Creek or other Australian products,

they have warning labels about consumption whilst pregnant, drinking and

driving and using heavy machinery, but the same product here, which is produced

in Australia, does not have a warning label.[91]

Consumer and nutritional

information

1.105

The Alcohol and Other Drugs Council of Australia suggested that

alcoholic products should also include nutritional information as part of the

health information requirements noting that presently 'many young women who

drink highly sweetened RTDs are unaware of how many calories they consume'.[92]

With young women being especially sensitive to their calorie intake, the ADCA emphasised

the point by using an analogy of a young woman at a party who may have consumed

six glasses of champagne being told that she had eaten six doughnuts:

'if you really looked at exactly what the calorific content is

of what you’ve consumed, you’d know that it was the equivalent of six doughnuts

and I don’t think you’d have been eating six doughnuts.’ So it is that sort of

message that can also help people to get a better appreciation of some of the

other associated harms of alcohol.[93]

1.106

Similarly the Public Health Association of Australia suggested that the

labelling requirements for alcohol products also outline information regarding

food content as required by other food products sold in Australia. They

commented:

The PHAA is keen to ensure that alcohol falls under the same

banner as other foods with regard to identifying content. Foods and beverages

other than alcohol are required to have this information so that consumers have

the ability to assess the health impact that foods and additives might have on

their own health and well-being. There is simply no good reason why alcohol

should be exempt.[94]

Efficacy of labelling alcohol

products

1.107

Several submissions questioned the effectiveness of health warning

labels on alcohol products. The Winemakers Federation of Australia described

mandatory health warning labels as a 'simplistic and ineffective approach to

public policy' and stated there was 'no evidence that shows that warning labels

on alcohol products lead to behavioural changes amongst those groups that are

at risk'.[95]

1.108

Lion Nathan doubted the effectiveness of warning labels on alcohol

products describing research from the United States conducted since the

introduction of US federal labelling legislation in 1989 which found no strong

evidence that labels have modified drinking behaviour. They noted that:

Disturbingly, there is also evidence that warning labels may

have unintended consequences, with a survey of young American college students

suggesting warning labels actually increased the attractiveness of alcohol.[96]

1.109

The National Centre for Education and Training on Addiction noted that a

number of other countries have introduced mandatory health warnings on the

labels of alcoholic beverages. However while there was 'some evidence of

consumer awareness of the messages conveyed by the warning labels, there is

very little research evidence to suggest that a change in alcohol consumption

has occurred as a result of these warnings'.[97]

VicHealth argued that while evidence regarding the effectiveness of health

information labels in altering drinking behaviour is inconclusive, there is

evidence to suggest a degree of increased awareness of alcohol related harms

due to advisory labels, combined with the effects of other public health

measures, may translate into a change in drinking behaviour.[98]

Health information

1.110

The health benefits of moderate consumption were seen by some as making

the case for health warnings on alcohol products more complex. Lion Nathan argued

that 'alcohol, unlike many other drugs, can be consumed safely in moderate

quantities and that moderate drinking can provide protection against a range of

health problems'. It listed these as including cardiovascular disease, adult

onset diabetes (type 2), cognitive function and dementia, and osteoporosis.

Lion Nathan recommended a full review of the health benefits of moderate

alcohol consumption be conducted before further consideration is given to health

information labels.[99]

1.111

However several submissions argued the harms caused by risky alcohol

consumption significantly outweighed any health benefits of moderate

consumption. For example the Salvation Army stated:

A popular argument against the introduction of warning labels is

the believed health benefits of moderate consumption of alcohol. But in fact it

is well established that the health benefits of alcohol consumption are limited

to specific circumstances and sub-populations which do not include women of child-bearing

age. According to various studies show... the protective factors apply only to

men over 45 and women over 49, and protect only against atherosclerosis and

thrombosis in these groups. Even in these groups the protective benefits are

not likely to outweigh the risks.[100]

Alcohol and Pregnancy

1.112

The health advisory labelling of alcohol products was supported by the National

Organisation for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Related Disorders (NOFASARD). It

noted that there is no research that has established a safe lower limit of

alcohol exposure to a developing foetus but there is a significant body of

accepted research that links excessive alcohol consumption by pregnant women

with permanent physical and neurological birth defects, known as Fetal Alcohol

Syndrome (FAS).[101]

1.113

NOFASARD also highlighted there was a very low level of awareness of

FASD in Australia and that the lack of a warning label on alcohol products

relating to the harm their use may cause, is a contributing factor to this low

level of awareness. They stated that:

We acknowledge that labelling alone may not be sufficient to

help prevent all cases of FASD, however we believe a health advisory label on

all alcohol products will raise awareness about alcohol's potential harm to the

unborn baby and this is the critical first step in any programme designed to

inform, influence and effect behaviour change.[102]

1.114

The Committee notes that FSANZ is currently considering an application

from the Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand to require health advisory

labels on alcohol products advising women concerning the risks of consuming

alcohol when planning to become pregnant or during pregnancy.[103]

FSANZ is assessing the impact of low maternal alcohol consumption on the

developing foetus and evaluating information on the incidence of FASD, the

drinking patterns of women of childbearing age and pregnant women in Australia

and New Zealand, and their knowledge of the risks to the foetus associated with

consuming alcohol during pregnancy.[104]

Food Standards Australia New

Zealand (FSANZ)

1.115

FSANZ noted that it had been requested to consider mandatory health

warning on packaged alcohol by the Australian New Zealand Food Regulation

Ministerial Council and would need to undertake consumer and economic research

to progress this report. In relation to developing a broader alcohol labelling

system for consumers, FSANZ stated that work beyond what had been requested by

the Ministerial Council would need to be in response to an application to amend

the relevant alcohol labelling standard or via a proposal to do the same at the

request of the Ministerial Council. It commented:

The Ministerial Council is responsible for the formulation of

policy guidelines which FSANZ must have regard to in developing food regulatory

measures. At present no policy formulation exists on the subject of alcohol

labelling. In the absence of such policy it would be very difficult for FSANZ

to develop a comprehensive alcohol labelling system.

The development of an alcohol information labelling system would

also need to be guided by an assessment of costs versus benefits through a

regulatory impact statement (RIS).

This further work would be resource intensive and without

additional funding FSANZ would need to reprioritise its current work plan.[105]

Constitutional limitations

1.116

Possible constitutional limitations with the amendments the Bill

proposed to the Food Standards Australia New Zealand

Act 1991 were highlighted in the Department of Health and Ageing

submission.

Food standards are mandated in the Australia New Zealand Food

Standards Code (the Code) and not in the legislation that establishes Food

Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ), its functions and powers and the

process by which the Code may be amended. Therefore, the amendment proposed in

the Bill is not appropriate.

The FSANZ Act is enabling legislation designed to provide FSANZ

with powers to develop food standards within the framework of an

inter-governmental agreement and a Treaty between Australia and New Zealand.

The FSANZ Act has no effect on State or Territory food law due to Commonwealth

Constitutional restraints. As a consequence States and Territories are

responsible for enforcement of the Code. Therefore there would be no capacity

for the States or Territories to enforce the proposed section 87A if it were to

be inserted into the Act as it would not be considered a food standard for the

purposes of the Code.

Proposed section 87A goes well beyond the enabling legislative

scheme by suggesting to [impose an] obligation on FSANZ to make a standard for

the labelling of alcohol and effectively imposing a law on the States,

Territories and New Zealand.[106]

1.117

The Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code is a compilation of

individual standards which acquire legal force through an intergovernmental

agreement, the Food Regulation Agreement, between the Commonwealth, states and

territories. Clause 23 of the Food Regulation Agreement sets out the adoption

process for those standards which FSANZ develops and approves. In effect,

jurisdictions will only adopt or incorporate into their domestic food law

standards that have been developed and approved by FSANZ. The proposed

amendment in the Bill to the FSANZ Act does not contemplate the development

process by FSANZ, so the Food Regulation Agreement would not enforce it.[107]

1.118

This issue was also raised by the Federation for Advertising Research:

The procedures for establishing a new FSANZ standard are in the

Act. There is extensive consultation and final adoption of the standard

requires the agreement of the Governments of the States and Territories as well

as New Zealand. Thus no one Government can impose a standard unless all of the

other Governments agree.[108]

Similarly the South Australian Government noted there was an

existing process for changes to labelling through FSANZ. It suggested 'any

changes to food labelling should be pursued through an application to FSANZ for

consideration'.[109]

OTHER ISSUES

1.119

There are some apparent drafting issues with the Bill in the additional

provisions amending the Food Standards Australia New

Zealand Act 1991. The Australasian Associated Brewers noted that 'proposed

Section 122A(3) of the Bill is poorly drafted as its intention is to void the

entire 'commercial television industry code of practice' including provisions

not relating to alcohol at all, while the equivalent radio code is not

similarly threatened'.[110]

1.120

Similarly the objects of the Bill include '(a) to limit the times at

which alcohol products are advertised on radio and television for the

protection of young people' (italic added). However, the proposed Section 122A

only refers to 'commercial television broadcasting licensees' rather than

including commercial radio broadcasting licensees.

CONCLUSION

1.121

While the Committee supports the broad aims and objectives of the

Alcohol Toll Reduction Bill 2007, it does not agree that the provisions of the Bill

represent the best approach to address the harms caused by alcohol in the

community. The inquiry highlighted some deficiencies with the current ABAC

Scheme for pre-vetting alcohol advertisements and adjudicating complaints. However

the Committee also notes the relatively low number of public complaints

recorded concerning alcohol advertising in recent years.

1.122

The Committee does not agree there is a compelling case for a dual

system of industry quasi-regulation and government regulation of alcohol

advertising on television and radio through a new Division in the Australian

Communication and Media Authority. Additional restrictions placed on radio and

television advertisements are likely to simply shift the advertising of alcohol

products to other media markets.

1.123

A consistent argument in evidence and from witnesses was that the

measures in the Bill (restricting radio and television advertising and the labelling

of alcohol products) would be most effective if they were part of a

comprehensive strategy to address the harms associated with alcohol

consumption. In Australia a broad national policy approach currently exists in

the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy and the National Alcohol Strategy 2006-2009.

The Committee notes that the Ministerial Council on Drugs Strategy is currently

developing a report for the Council of Australian Governments which will

include consideration of possible standards and controls for alcohol

advertising targeting young people. The Committee considers this policy

framework is the appropriate means to develop and implement changes to alcohol

advertising.

1.124

One area of alcohol advertising which particularly concerned the

Committee is the exception for advertising of alcohol products during coverage

of live sport on commercial television. This exception clearly results in

children being exposed to alcohol advertising. The Committee notes that the

members of the ABAC Scheme Management Committee have generally been receptive

to suggestions for reform and improvement in the past. The Committee also notes

the on-going monitoring and reform of the ABAC Scheme through the Ministerial