Chapter 2 - Health service delivery: Regional, rural and remote Australia

2.1

It was clear from the evidence received that the operation and

effectiveness of the travel schemes can only be understood within the broader

context of health service delivery in rural and remote Australia. A number of

supply and demand issues were presented to the Committee, which impact on the

efficacy of the current travel schemes and present future challenges for health

service delivery in rural and remote areas.

Regional, rural, remote: demography

2.2

There are three principal systems for defining non-metropolitan areas

(areas with less than 100,000 inhabitants) in Australia: the Australian

Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC), which defines an area's

'urbanness/ruralness'; the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA),

which defines an area's level of accessibility to goods and services; and the

Rural, Remote and Metropolitan Areas (RRMA) classification.[1]

2.3

The ASGC system was established by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Sections of the States and Territories are classified as follows:

- Major Urban: urban areas with a population of 100,000 and over

- Other Urban: urban areas with a population of 1000 to 99,999

- Bounded rural locality: rural areas with a population of 200 to

999

- Rural balance: the remainder of the states and territories

- Migratory: areas composed of offshore, shipping, and migratory

collection districts.[2]

2.4

The ARIA system was developed by the National Key Centre for Social

Applications of Geographical Information Systems (GISCA) at the University of Adelaide.

It has been summarised as follows:

Highly accessible: locations with relatively unrestricted

accessibility to a wide range of goods, services and opportunities for social

interaction.

Accessible: locations with some restrictions of some goods,

services and opportunities for social interaction.

Moderately accessible: locations with significantly restricted

accessibility of goods, services and opportunities for social interaction.

Remote: locations with very restricted accessibility of goods,

services and opportunities for social interaction.

Very remote: locations with very little accessibility of goods,

services and opportunities for social interaction.[3]

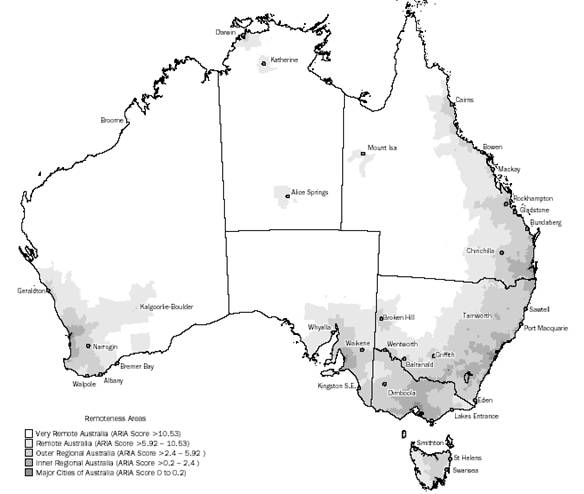

2.5

The following discussion draws extensively on publications by the

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), which uses the ASGC categories

of Major Cities, Inner Regional, Outer Regional, Remote and Very Remote. The

following map shows these classifications.

Figure 2.1: Australian Remoteness Areas

Source: http://www.abs.gov.au [accessed 31.8.07]

2.6

The regions outside Major Cities encompass an extremely diverse area

ranging from coastal or inland areas within commuting distance of Major Cities to

the sparsely populated, hot and dry

outback. Many areas outside Major Cities, predominantly on the coast, attract

older people in retirement. A significant proportion of the occupations in

regional and remote areas (for example mining, transport, forestry, commercial

fishing and farming) entail higher levels of risk than other occupations. One

in ten people in the non-metropolitan workforce is engaged in agriculture.

2.7

In Australia, two-thirds of the total population live in Major Cities,

with 21 per cent, 11 per cent, 2 per cent and 1 per cent living in Inner Regional,

Outer Regional, Remote and Very Remote areas respectively. The Indigenous

population of Major Cities is only 1 per cent (representing 30 per cent of the total

Indigenous population), increasing to 2 per cent and 5 per cent in Inner and

Outer Regional areas (43 per cent of the total Indigenous population), 12 per

cent in Remote areas and 45 per cent in Very Remote areas (27 per cent of

the total Indigenous population).[4]

2.8

Males outnumber females in almost all age groups in the more remote

areas. This is largely influenced by the non-Indigenous population. The number

of Indigenous males in each area is similar to the number of females.

2.9

Remote area populations tend to have proportionally more children and

working age males, and fewer elderly people than other areas. Regional areas

have proportionally lower numbers of people aged 25-44 years, higher numbers of

people aged 45-74 years and similar or slightly lower numbers of people older

than 75 years than other areas. In regional areas, children make up a higher proportion

than in Major Cities, but lower than in remote areas.[5]

Measures of health status in rural and remote areas

2.10

People in rural and remote areas generally do worse than other

Australians on a range of health status measures. There are higher mortality

rates, poorer dental health and higher levels of mental health concerns. This

is likely to be a result of a mix of behavioural, socioeconomic factors and

poorer access to health services.

2.11

The following is a brief overview of the findings of the AIHW's 2005 report

Rural, regional and remote health – Indicators of health which includes

measures of both health status and the determinants of health.[6]

2.12

The AIHW reported the following indicators of rural and remote health

status:

- Chronic disease: overall there was no significant difference

between the prevalence of self reported chronic diseases in regional areas and

Major Cities;

- Injury: people in regional areas were 1.2 times more likely to

self-report a recent injury and more likely to self-report a long-term

condition due to injury;

- Mental health: depression was more prevalent in regional areas;

- Dental health: children had more decayed, missing or filled teeth

in regional/remote areas;

- Communicable diseases: the rates of communicable disease

notification tend to increase with remoteness;

- Birthweight: very low birthweight babies were more prevalent compared

to Major Cities;

- Disability: disability was more prevalent compared to Major

Cities;

- Reduced activity because of illness: the average number of days

of reduced activity because of illness was greater in regional areas than in

Major Cities;

- Life expectancy: life expectancy was highest in Major Cities and

lowest in Very Remote areas likely due to the much lower Indigenous life

expectancy;

- Overall mortality: compared with their counterparts in Major

Cities males and females from regional and especially remote areas had higher

rates of death and death rates roses with increasing remoteness – this is about

3,300 additional deaths annually;

- Perinatal mortality: compared with their counterparts in Major

Cities rates of foetal and neonatal death were higher in regional and

especially remote areas which is at least partly a reflection of Indigenous

population distribution; and

- Causes of death: the leading causes of the higher death rates

experienced in regional and remote areas are mainly circulatory diseases (42

per cent of the excess deaths) and injury (24 per cent) with respiratory

disease and cancers contributing about 10 per cent of the 'excess' deaths

each.[7]

2.13

The AIHW also noted that rural and regional areas had poorer determinants

of health including less access to fluoridated water (only 30-40 per cent of

those in regional and Remote areas, and 25 per cent of those in Very Remote

areas have access to fluoridated water). Other determinants highlighted by the

AIHW included:

- higher unemployment rates in regional and remote areas compared

to Major Cities;

- lower after-tax household incomes in regional areas;

- the main sources of employment are agriculture, forestry, fishing

and mining with less employment in manufacturing;

- the three indexes of relative socioeconomic disadvantage (economic

resources, and education and occupation) outcomes were better in Major Cities

than in regional and remote areas;

- birth rates were higher for women in regional and remote areas

than for those in Major Cities, and increased with increasing remoteness;

- homicide death rates were substantially higher in Remote and Very

Remote areas (although the actual numbers of deaths were relatively small);

- there is more household crowding in Very Remote areas;

- food prices increased with remoteness – food prices in Very

Remote areas were between 14 per cent and 19 per cent higher than in the

Australian capital cities;

- fuel prices also increased with remoteness; and

- the cost of housing decreased with remoteness.

2.14

People in regional areas are more likely to smoke and more likely to

engage in risky alcohol consumption. Illicit drug use is more prevalent in

regional areas. The situation in remote areas is unclear. People in regional

areas are more likely to be sedentary and more likely to be overweight.[8]

2.15

The AIHW noted that people who live away from Major Cities and for whom

access to health services is restricted may be disadvantaged because of

different access to:

- preventive services such as immunisation and information allowing

healthy life choices;

- health management and monitoring;

- specialist surgery and medical care;

- emergency care, for example ambulance;

- rehabilitation services after medical or surgical intervention;

and

- aged care services.[9]

2.16

Evidence received by the Committee also emphasised the variation of

health outcomes in regional and remote Australia.[10]

2.17

The Australian Rural and Remote Workforce Agencies Group (ARRWAG) cited

the following statement from J. Dade-Smith in Australia's Rural and

Remote Health. A social justice perspective:

Australians living in rural areas have unique health concerns

that relate directly to their living conditions, social isolation,

socioeconomic disadvantage and distance from health services. They have death

rates that are double the urban rate due to injury, triple due to road

accidents and double due to falls in the aged. Hospital admission rates due to

diabetes are four times the urban admission rate. Yet rural people have lower

access to health care compared with their metropolitan counterparts because of

distance, time factors, costs and transport availability.[11]

2.18

Focusing specifically on breast cancer, a study commissioned by the

pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline revealed that the higher mortality rate

of rural and remote women with breast cancer was due, in part, to 'later

diagnosis and less access to cancer screening and treatment services in

regional areas'.[12]

Other witnesses also noted that rural women are significantly more likely to

undergo mastectomy rather than breast-conserving therapy unlike urban women. It

was argued that rural women were less likely to travel to have breast-conserving

surgery at an urban treatment centre for adjuvant therapy.[13]

2.19

The Cancer Council Australia also pointed to poor outcomes for cancer

patients in rural and remote areas:

There is growing epidemiological evidence that cancer mortality

rates increase significantly in step with geographic isolation. A study

published in the Medical Journal of Australia in 2004 showed that people with

cancer in regional NSW were 35% more likely to die within five years of

diagnosis than patients in cities. Mortality rates increased with remoteness.

For some cancers, remote patients were up to 300% more likely to die within

five years of diagnosis.

A study published by COSA [Clinical Oncological Society of

Australia] in 2006 and editorialised in the Medical Journal of Australia mapped

the provision of rural/remote oncology services across Australia. The study was

the first national analysis to statistically demonstrate what has long been assumed:

that access to essential cancer care in all disciplines decreases nationwide as

communities became more isolated.[14]

2.20

There is also evidence on differences in the rate at which people from

major cities, regional and remote areas were admitted to hospital for a range

of surgical procedures in 2002–03. For example, rates of coronary artery bypass

graft and coronary angioplasty were lower among people from regional and

especially remote areas (and at odds with the pattern of death rates due to

coronary heart disease). Compared with residents of Major Cities, rates of:

- diagnostic gastrointestinal endoscopy and myringotomy were also

lower for residents of regional and especially remote areas;

- appendectomy and lens insertion were higher for residents of

regional and remote areas; and

- cholecystectomy, hip replacement, revision of hip replacement,

knee replacement, hysterectomy, tonsillectomy and arthroscopic procedures were typically

higher for residents of regional areas and lower for residents of remote areas.[15]

2.21

The Australian Medical Association (AMA) concluded that:

A driving factor behind these poorer health outcomes is the

difficulty people in regional and remote areas face in accessing specialist and

primary health care. Isolation and lack of services make it complicated for

these patients to receive preventive services and manage chronic diseases.

Consumers needing to travel long distances to access services can face considerable

disruption and personal financial cost.[16]

Access to services

2.22

Limited access to health services is a significant issue for people

living in rural and remote Australia. An inadequate supply of hospital and

other health services and workforce shortages in these areas were identified as

key factors.

Supply of hospital services

2.23

The provision of hospitals and hospital beds are concentrated in Major Cities

and regional areas. Some 22 per cent of public hospitals (but only 4.8 per cent

of the available beds) are located in remote and very remote areas (compared

with 6 per cent of the population).[17]

Most hospitals in remote areas are public hospitals. However, hospitals are

less likely to be accredited in regional and remote areas.

2.24

Most smaller rural hospitals are not equipped to provide the full range

of specialised services and people must be transferred to larger regional or

metropolitan centres. Some smaller hospitals operate as Multi-purpose Services

(MPSs) and provide a range of services such as emergency triage, hospital care

and aged and community care.

Workforce shortages

2.25

The supply of health workers in regional areas has long been an issue.

The AIHW reported that the supply of health workers declines with remoteness.

Table 2.1 shows the number of employed medical practitioners in 2003 by type of

practitioner and remoteness area.

Table 2.1: Employed medical

practitioners, by type of practitioner and remoteness areas

|

|

Major

Cities

|

Inner

Regional

|

Outer

Regional

|

Remote

|

Very

Remote

|

Total[a]

|

|

Type

of medical practitioner

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clinicians

|

39,389

|

7,074

|

2,948

|

468

|

212

|

51,819

|

|

Primary

care practitioners

|

15,132

|

3,901

|

1,740

|

301

|

152

|

21,919

|

|

Hospital

non-specialists

|

4,561

|

659

|

359

|

69

|

42

|

5,915

|

|

Specialists

|

14,580

|

2,164

|

665

|

79

|

15

|

18,093

|

|

Specialists-in-training

|

5,116

|

350

|

185

|

20

|

3

|

5,892

|

|

Non-clinicians

|

3,621

|

372

|

205

|

30

|

18

|

4,388

|

|

Total

|

43,010

|

7,446

|

3,154

|

498

|

230

|

56,207

|

|

No.

per 100,000 population

|

326

|

179

|

155

|

154

|

130

|

283

|

|

Percentage

female

|

32.6

|

27.4

|

30.3

|

31.5

|

35.0

|

31.9

|

|

Average

age (years)

|

45.7

|

46.8

|

45.1

|

44.7

|

43.4

|

45.9

|

|

Average hours worked per week

|

44.2

|

44.8

|

46.2

|

47.8

|

50.0

|

44.4

|

[a] Includes 1,870 medical practitioners who did not

provide information on the location of their main job.

Source:

Australian Institute of Health and

Welfare, Australia's Health 2006, p.325.

2.26

The AIHW noted that to some extent, the decrease in supply of medical

practitioners was countered by patterns of average hours worked by medical

practitioners which increased from 44.2 hours per week in Major Cities to 50.0

hours per week in Very Remote areas. The AIHW also noted that, consistent with

the placement of the large teaching hospitals near population centres, Major Cities

and Inner Regional areas together accounted for 84.3 per cent of specialists

and 92.8 per cent of specialists in training.

2.27

ARRWAG commented on access to primary health care providers,

particularly GPs and noted that in 1998 the Australian Medical Workforce

Advisory Committee (AMWAC) estimated the shortage to be in the region of 1240

GPs. Four years later, in 2002, the AMA commissioned a report from Access

Economics which estimated that there was a shortage of between 700 and 800 full

time equivalent GPs in rural and remote areas.[18]

2.28

The nursing workforce is more evenly distributed across regions than

medical practitioners, and shows a smaller variation in number per 100,000

population. Nurses in regional and remote Australia are older than in Major

Cities and tended to work longer hours per week in Remote and Very Remote

areas. Table 2.2 show employed registered and enrolled nurses in 2003.

Table 2.2: Employed registered and enrolled nurses, by

remoteness areas of main job, 2003

|

|

Major

Cities

|

Inner

Regional

|

Outer

Regional

|

Remote

|

Very

Remote

|

Total[a]

|

|

Number

|

147,670

|

48,440

|

22,719

|

3,870

|

1,936

|

236,645

|

|

No.

per 100, 000

|

1,120

|

1,167

|

1,115

|

1,193

|

1,095

|

1,191

|

|

Percentage

female

|

91.2

|

90.9

|

93.9

|

93.3

|

89.7

|

91.4

|

|

Percentage

registered

|

83.3

|

75.0

|

71.5

|

73.4

|

79.1

|

79.9

|

|

Average

age (years)

|

42.5

|

44.2

|

44.3

|

44.2

|

44.3

|

43.1

|

|

Average hours worked per week

|

32.8

|

31.7

|

32.3

|

34.1

|

37.8

|

32.5

|

[a] Includes 12,009 nurses who did not provide information

on the location of their main job.

Source:

Australian Institute of Health and

Welfare, Australia's Health 2006, p.327.

2.29

The distribution of dentists in Major Cities is more than three times

that in Remote and Very Remote areas with the rate dropping from 57.6 to 18.1 per

100,000 population.[19]

2.30

The Rural Doctors Association of Australia (RDAA) also commented on the

discrepancy between the levels of ill health that people in rural and remote areas

and the health dollars spent in those areas:

Even though rural and remote Australia has a more aged and a

'sicker' population there is less spent on their health needs compared to their

city counterparts. Medicare figures provided by the Department of Health and

Ageing also show that if you lived in a capital city that the average general

practitioner benefit paid per capita was $195 but if you lived in a remote area

of Australia that this figure falls to $120...Many specialist services are also

not available or viable in rural areas either because of workforce shortages,

low concentrations of patients or because they require the facilities of a

large hospital.[20]

2.31

While the analysis of rural services and workforce gives an indication

of the general limits to access, there are differences between jurisdictions

and within regions. The Australian Rural Nurses and Midwives (ARNM) explained:

There are considerable differences between states with regard to

the geographical spread of services. Remoteness factor cannot only be measured

by geographical location or distance; regional health services for example are

in much greater numbers in rural New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland as

opposed to Western Australia and South Australia. As such specialist services

in these states are only available in the capital cities.[21]

Diminishing services in regional,

rural and remote areas

2.32

Many witnesses noted that there has been a continuing diminution of

services in rural and remote areas with a decline in GP numbers and a downgrading

of hospital services. The Country Women's Association of NSW stated that:

With the down-grading of country and regional hospitals it is

now necessary for patients to travel greater distances. In the past it was not

unusual for specialists to regularly visit country and regional hospitals which

meant that patients were able to access locally many of the services for which

they now need to travel vast distances.[22]

2.33

The Shire of Sandstone provided an example of the decrease in access to

general practitioners:

In Mount Magnet the situation has become quite dire, in that,

from having a full-time general practitioner a couple of years ago, the town of

700 people is now serviced once a month by a visiting medical practitioner from

Geraldton who sees between 60 and 70 clients for one day a month. The nursing

posts have gone down from four nurses to one. It is a town which is

experiencing significant social and health problems in terms of drug and

alcohol abuse, which of course precedes child abuse.[23]

2.34

The Australian Nurses Federation (ANF) raised concerns about access to obstetric

services:

Access to health care also means access to services to assist

with normal life events, such as maternity and birthing services; the ANF is

very concerned that people in rural and remote Australia are being denied

access to birthing services with over 130 birthing services in country areas

closed in the last decade.[24]

2.35

The RDAA also commented that half of the obstetric services had closed

in the last 10 years which meant 'that many GP obstetricians and obstetrician

gynaecologists who want to provide services are unable to provide those

services in their community'.[25]

2.36

ARRWAG also reported a reduction in services being offered by GPs:

...there has been a decline in the proportion of GPs providing

procedural services – down from 24% in 2002 to 21.5% in 2005. Rural GPs have

traditionally been more likely to undertake procedures than their urban

counterparts because of a lack of specialists in rural and remote areas. A

decline in GPs undertaking this work may be a major factor in people living in

rural and remote areas having to travel to visit a medical specialist in

addition to an on-going decline in proceduralist GPs.[26]

2.37

WA Country Health Services indicated that workforce issues were impacting

on the delivery of services to the extent that a regional 'hub and spoke' model

had been introduced in an attempt to maintain service delivery levels:

Obstetric services are becoming harder to deliver. Anaesthetic

services are harder to deliver. General surgeons are in scarce supply; they

threw away the mould and they are not making generalist positions. Procedural

trained GPs that are willing to go out into the bush, which are the backbone of

our country hospital system, are not being made any more. I would contend, that

is just going to be the way the rural health service delivery is going to be.

That is why we have introduced a regional hub-and-spoke model because it is the

only way we think that you can try and maintain at least some services in a

region in the face of those workforce difficulties.[27]

2.38

However, witnesses commented that the hub and spoke model does not

always take into account the transport problems of the area. The Shire of

Ashburton WA stated:

The issues are: hub and spoke does not work because there is no

spoke in the sense that there is no public transport; there is no commercial

link or integration of any type whatsoever between any town in the Pilbara at

the air level; there is absolutely no land service of a commercial public

nature; and, all interaction is through private travel. We are talking about

extremely long distances and times. Most one way distances are 400 to 500

kilometres or more. This puts great pressure on patients because, the way the

system works, carers do not get a great deal of support through the PATS

system. Also, the road systems, the distances travelled, the safety risks from

animals on the road, the sheer heat and such types of things mean that it is a

test for an able-bodied, healthy person, let alone someone who is suffering an

illness.[28]

2.39

The Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) cited two reasons for the centralisation

of services. Firstly, evidence shows that sufficient patient 'throughput' is

required to achieve 'safe and appropriate clinical outcomes'. To put it simply,

specialists need the opportunity to practice. Secondly, advances in medical

technology have resulted in the development of sophisticated procedures and

(often highly expensive) medical equipment. Due to the cost and degree of

specialisation, treatments are restricted to a few health centres:

Because of the needs for cost effective utilisation of expensive

equipment and/or to achieve and maintain clinical competence in complex and

costly procedures, it may be feasible to have only a limited number of

health-care establishments, such as hospitals, providing certain specialised

health services.[29]

2.40

Haematology services in Western Australia are an example of centralised

services:

Throughout regional Western Australia there are extremely

limited haematology services available. There is limited low level care

available in Bunbury and in Albany. These treatment areas provide only simple

administration of chemotherapy. They are not resourced for admissions of an

un-well immunised compromised patient.

No haematology patient diagnosed within regional WA would be

able to avoid multiple trips to Perth as is evidenced by the following list of

diagnostics and treatment that are not available elsewhere:

- all haematologist appointments.

- scanning and radiology

appointments.

- any nuclear medicine scans.

- chemotherapy regimes – either

preformed as inpatient or outpatient.

- admission to treat neutropenia

infections post chemotherapy.

- access to specialised physio;

dietetics; rehabilitation and psychological health professionals.[30]

2.41

While there may be sound reasons for centralisation, the lack of

services places greater pressure on rural GPs to provide more specialised

services and manage more highly complex cases:

Clearly, if patients do not have access to specialist care in

their community and they do not have access to, say, the Alfred or Prince of

Wales hospital, those patients end up being managed by the GP in their

community often without being able to get support from their specialist

colleagues. There are some money issues involved, but it is broader than that.

There are training issues as well. I think that we really have to make it

attractive for GPs to train in procedural specialties, that is, anaesthetics,

obstetrics.[31]

ARRWAG also concurred that work intensity was a problem with

attracting and retaining rural GPs.[32]

An increasing demand for PATS

2.42

Witnesses argued that the demand for PATS will continue to increase over

time as services in regional, rural and remote areas continue to decline, the

population ages and other issues such as more sophisticated and more expensive

medical technologies are introduced.

Future pressures on PATS

2.43

DoHA identified 'future pressures' that could impact on patient transport,

with more patients needing to travel to receive treatment:

- increased health needs of the ageing population;

-

increase in the number of patients with chronic conditions and,

consequently, complex health needs;

- advances in medical technology:

-

patient expectations of treatment available to them grows as

treatment becomes more effective and previously untreatable conditions become

treatable;

- highly specialised and expensive equipment is provided in limited

hospitals/specialist centres requiring patients to travel for treatment; and

- possible rationalisation of hospital and health services by State

and Territory governments.[33]

2.44

State and Territory Governments concurred with the majority of DoHA's observations,[34]

with the impact of the drought also identified as increasing demand. The Victorian

Government commented that the lack of access to Commonwealth-funded medical and

allied health services was also contributing to demand pressures, while South

Australia argued that 'the level of growth [in demand for PATS] is causing

increasing pressure on SA resources while the Australian Government

contribution has grown more slowly'.[35]

2.45

The Rural Doctors Association of Australia similarly noted that the

ageing population will impact on demand:

Chronic disease (conditions likely to persist for at least six

months) constitutes about 80% of the burden of disease in Australia today, a

figure which will rise with demographic ageing.[36]

2.46

At the same time, the ageing population is impacting on the medical

workforce with more than 50 per cent of the GP workforce in rural and remote Australia

aged over 45 years.[37]

As demographic ageing continues, there will be a relatively smaller pool of

professionals to attract to rural and remote areas.[38]

A changed operating environment

2.47

Witnesses argued that PATS as it was envisioned in the 1980s is no

longer sustainable. The environment in which PATS operates has changed

significantly. As discussed above, people in regional, rural and remote areas

have poorer health status than other Australians; there are significant

workforce shortages which are exacerbated by the need to centralise services

due to cost and technology imperatives; and ageing is impacting on both the

general population and the medical professional population. The WA Country

Health Service commented:

The difficulty I think for us is that we are losing ground. We

have had quite a lot of success in recent years but we are losing ground with

that strategy at the moment because the workforce shortages that we forecast

five years ago are now with us and they are getting worse. So we have lots of

vacancies, we have lots of services where the skills mix is skewed and out of

plumb; we have lots of services that are completely failed and we have some

that are so fragile they work some days and not on others. The Pilbara region

is absolutely in tremendous difficulty at the moment with fragile services. We

have enormous numbers of overseas trained doctors who are not familiar with the

Western Australian system and who have varying skills mix, so our services have

never been so challenged.[39]

2.48

The WA Country Health Service went on to comment that to try and operate

PATS in the same old way, 'where the services that would ordinarily be

available locally are sometimes there and sometimes not, is starting to create

some more tension'.[40]

2.49

The South Australian Government also commented on the changes in health

care delivery since the introduction of patient assisted travel schemes:

The schemes started from a base where they focused on access to

medical specialist services. Health care delivery has changed over the last 20

years and it is critical that PATS look towards expanding to include access to

primary and allied health care services. The cost implications of expanding

need to be considered and the Australian Government needs to provide its fair

share of funding support.[41]

2.50

In addition, the schemes have not evolved as advances in treatments and

care have evolved. A case in point is the treatment of cancer where access to a

multidisciplinary team increases survival rates and decreases adverse outcomes.

The NRHA stated that:

Complete cancer care often includes care coordination and

planning between medical, surgical and other cancer care specialists,

specialist investigative procedures, surgery, radiation therapy and

chemotherapy, with a range of frequencies and intensities, and monitoring

requirements. This is necessary for some conditions, in order to match a

subsequent therapy with the patient's response to an earlier treatment. Often,

acute side-effects are debilitating for the patient. A secure home-like

environment, whilst experiencing unpleasant side effects of some treatments

away from home, with support from relevant carer/s, will assist treatment

compliance and maximise benefit. The failure of the schemes to genuinely cover

essential care for many cancer patients probably contributes to poorer survival

rates in cancer among people in rural and remote areas.[42]

2.51

Other examples include access to coordinated treatment and support for

chronic conditions such as epilepsy, kidney disease and Parkinson's disease

where access to a range of allied health services can decrease the adverse

impact of the disease through physiotherapy, specialised nursing care and

occupational therapy.

2.52

At the same time, witnesses commented that it was short-sighted for

governments not to provide adequate access to health services as in the long-term

costs incurred were greater through health complications and economic loss and could,

in fact, undermine other health initiatives.

2.53

The RDAA argued that there was a 'compelling case' for increasing the

level of benefits because country people are 'just not getting the access that

they used to get'. Not providing good transport assistance schemes is a false

economy as the likely outcome will be additional health system costs being

incurred in both Federal and State funded areas. This is due to late treatment

of conditions and increased costs to the community associated with an increased

burden of illness and even avoidable and premature death.

In the long run, one would think, one would achieve better

outcomes. But it would be a lot less expensive for

the Commonwealth in the long run...if we were able to assist people to access

preventive care and screening in antenatal care and so on, thus saving money on

acute healthcare in the long run.[43]

2.54

The RDAA also noted that other initiatives could be undermined by the

lack of patient transport. For example, the Commonwealth Bowel Cancer Screening

Program – which enables people in any part of the country to be screened – is

not coordinated with follow-on care. People in rural and remote areas with a

positive test result still face enormous access issues in securing further

tests and treatment. RDAA research showed that following a positive screening

test a rural patient may have to wait six months or more to get a colonoscopy

which is 'a disaster for those people'.[44]

2.55

Dr Eduard Roos of the Southern Queensland Rural Division of General

Practice concluded that 'prevention is better than cure' and told the Committee

that:

...there is a cost saving if we can get the patient to see the

specialist sooner rather than later. So for us it is very important to make

sure that our patients can access the services.[45]

2.56

However, NSW Health argued that other factors such as 'access to carers

for children' and 'potential loss of income' impact on people's decisions about

how, when and if to travel to receive health care, as well as the adequacy of

the travel schemes. As such, NSW Health concluded:

[I]t would be extremely difficult to draw solid connections

between improved travel and accommodation support and clinical outcomes for

patients given the number of variables that affect a patient's clinical

outcomes.[46]

Conclusion

2.57

The health outcomes of people living in rural, regional and remote communities

are poorer than those in major cities in Australia. As discussed above, the

reasons for this are multifaceted and include a range of socioeconomic and

behavioural factors.

2.58

It is evident that rural, regional and remote communities are facing considerable

disadvantage in accessing services that those in major cities take for granted.

While the Committee acknowledges that many factors contribute to decisions to

travel (or not to) for treatment, the schemes that have been put in place to

assist with access should not themselves form a barrier to that access.

2.59

The Committee considers that, although there are considerable challenges

in providing services to a dispersed population, it is imperative that access

to services be improved. The failure to do so means health priorities are

undermined; costs to government may increase in the long term and most

importantly, the health status of those living in rural, regional and remote

communities will not be improved.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page