Chapter 3 - Out-of-home care - Foster children

Introduction

3.1

This chapter provides information about contemporary out-of-home

care for children in Australia.

It includes a discussion on the types of care available, details about changes

from institutional care to home-based and family care for children in need of

care, the number of children and young people accessing services and problems

and situations for children and young people in out-of-home care. Chapter 4 discusses

the foster carers and other people and organisations who provide various forms

of out-of-home care to children and young people.

Moves from children's institutional care to foster care

Foster care has now replaced institutionalisation. Multiple

placements have replaced the turnover of staff of the institutions. The high

cost of institutionalisation has been replaced [by] low cost under resourced

foster carers. Children still experience similar difficulties, system abuse,

lack of support when they leave, inadequate support while they are in care,

poor education and so on. The problems of children in care continue to be much

the same. Nothing has really changed.[257]

...in Victoria,

we have a crisis in out-of-home care. We are losing carers. We have got

multiple placements. We have got a child protection system in crisis...[258]

3.2

As noted in Forgotten

Australians, from Australia's

earliest times until the 1960s alternative care for children whose families

were unable to care for them oscillated between the use of large institutions

such as orphanages and other forms of care such as foster care. Research in the

1950s and 1960s drew attention to the adverse effects of institutional care on

children. Other research on maternal deprivation linked emotional adjustment

and mental health to maternal love and care in childhood. As a result,

'government and non-government child welfare agencies reviewed their practices

towards children in the light of this emerging research'.[259] Governments looked to care by family

members or foster care rather than large institutions for children in need of

out-of-home care.

3.3

The move to foster care occurred at different times

across jurisdictions, with Western Australia

being the first State to encourage foster care in the late 1950s. In Queensland

the number of children in institutions declined from the 1960s. In Victoria

and New South Wales the

implementation of the policy favouring foster care was slower: the number of

children in institutional care increased throughout the 1950s and 1960s, but

declined rapidly from the early 1970s. In New South Wales

the last of the State institutions closed following the release of the Usher

report in 1992.[260] Centacare-Sydney

commented:

By the 1970s foster care was being encouraged as a preferred

model of out-of-home care and most Catholic orphanages in NSW were closed by

the mid-1980s.[261]

3.4

Currently, government policy and practice is to

maintain children within the family if possible and to place a child in

out-of-home care only if this will improve the outcome for the child. If it is

necessary to remove the child from his or her family, various options are

available. Ideally, foster care with early intervention and prevention support

could be used to help families temporarily and keep children out of the welfare

system. In reality, foster care is becoming long term for many families.

Children are entering care at a young age and staying there for longer periods

and the numbers of children in care are increasing.[262] Professor

Dorothy Scott

has noted that there is also a lack of stable residential care options which

are often the most appropriate care for 'high-risk children, that is, those

children with extremely anti-social behaviour'.[263]

3.5

Evidence is that children who have been in out-of-home

care: have poor life opportunities; miss out on an education; feature highly in

homeless populations and the juvenile justice system; do not always receive

adequate dental or medical care; often gravitate to substance abuse; and are

more likely than their contemporaries not in care, to have thought of or

attempted suicide. Sadly, many children and young people in care do not even

know why they are not with their families and may think that it is their own

fault they are in care.[264] At times

they are vulnerable to the actions of the very people who should be protecting

them but often they simply do not have the capacity or skills to voice their

concerns about any bad treatment.[265]

3.6

These above findings about outcomes for many out-of-home

care children are similar to those from the Committee's earlier report into

institutional care, Forgotten Australians,

relating to children who spent their childhoods in orphanages and other

institutions from Australia's

very earliest times until the 1970s. That report exposed many disturbing

accounts of abuse of children including neglect, separation from families and

deprivation of food, education and healthcare, all of which took a toll on the

children's emotional development, as noted in the report:

The long-term impact of a childhood spent in institutional care

is complex and varied. However, a fundamental, ongoing issue is the lack of

trust and security and lack of interpersonal and life skills that are acquired

through a normal family upbringing, especially social and parenting skills. A

lifelong inability to initiate and maintain stable, loving relationships was

described by many care leavers who have undergone multiple relationships and

failed marriages.

Their children and families have also felt the impact, which can

then flow through to future generations.

The legacy of their childhood experiences for far too many has

been low self esteem, lack of self confidence, depression, fear and distrust,

anger, shame, guilt, obsessiveness, social anxieties, phobias, and recurring

nightmares. Many care leavers have tried to block the pain of their past by

resorting to substance abuse through life-long alcohol and drug addictions.

Many turned to illegal practices such as prostitution, or more serious

law-breaking offences which have resulted in a large percentage of the prison

population being care leavers.

For far too many the emotional problems and depression have

resulted in contemplation of or actual suicide.

Care leavers harbour powerful feelings of anger, guilt and

shame; have a range of ongoing physical and mental health problems...and they

struggle with employment and housing issues.[266]

Contemporary out-of-home care

3.7

The Committee received wide-ranging evidence about Australia's

out-of-home care systems including that relating to the ever-increasing number

of children needing to be placed in care because of parental drug or substance

abuse, high levels of family violence and subsequent abuse and neglect, and

continuing difficulties in recruiting and keeping adequate numbers of foster

carers to meet emerging needs.

Types of out-of-home care

3.8

Out-of-home care is defined as out-of-home overnight

care for children and young people under 18 years of age where a State or

Territory makes a financial payment.[267]

Out-of-home care is either formally or informally arranged. Informal care

refers to arrangements made without intervention by statutory authorities or

courts. Formal care occurs following a child protection intervention (either by

voluntary agreement or court order). It can occasionally result from a Family Court

agreement. A large part of formal care is authorised by government departments

and provided directly or by non-government agencies under contract.[268]

3.9

Out-of-home care includes residential care, foster care

and relative/kinship care. Children in care can be placed in a variety of

living arrangements or placement types. The Australian Institute of Health and

Welfare (AIHW) uses the following categories in the national data collection:

- Home-based

care – where placement is in the home of a carer who is reimbursed for

expenses in caring for the child. The three categories of home-based care are:

- foster

care – where care is provided in the private home of a substitute family

which receives a payment that is intended to cover the child's living expenses;

- kinship

care – where the caregiver is a family member or a person with a

pre-existing relationship with the child;

- other home-based care – care in private homes that

does not fit into the above categories.

- Residential

care – where placement is in a residential building whose purpose is to

provide placement for children and where there are paid staff. This includes facilities

where there are rostered staff, where there is a live-in carer and where staff

are off-site (for example, a lead tenant or supported residence arrangement).

- Family

group homes – where placement is in a residential building which is owned

by the jurisdiction and which are typically run like family homes, have a

limited number of children and are cared for around-the-clock by resident

substitute parents.

- Independent

living – where children are living independently, such as those in private

boarding arrangements.

- Other –

where the placement type does not fit into the above categories or is unknown.[269]

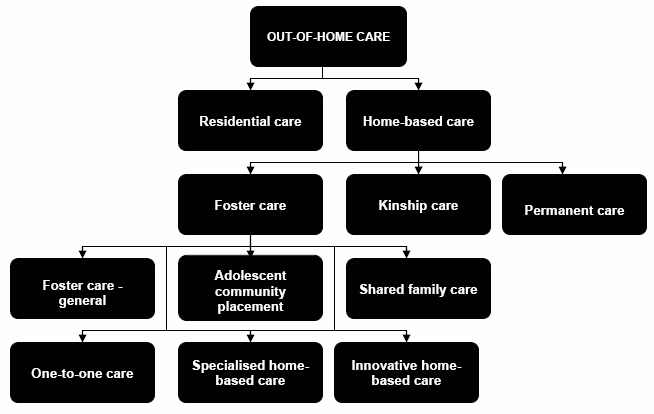

3.10

The different types of placement in out-of-home care

can be seen in the diagram of out-of-home care arrangements in Victoria

at Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1:

Out-of-home care in Victoria

Source:

Department of Human Services, Public Parenting: A review of home-based care in Victoria, June 2003, p.12

3.11

Jurisdictions utilise each form of out-of-home care to

a different extent: compared with other jurisdictions, in 2003-04 Queensland

and South Australia had a

relatively high proportion of children in foster care (74 per cent and 78 per

cent respectively) and New South Wales

had a relatively high proportion of children placed with relatives or kin (56

per cent). In some jurisdictions there is a trend toward kinship care as it

reflects government policy that children should be placed with an adult to whom

a child has an established attachment as the preferred option. In Western

Australia placement in relative/kinship care

increased from 26 per cent of out-of-home care at June 2000 to 37 per cent at

June 2004. In the same period, relative/kinship care in the Northern

Territory increased from 15 per cent to 23 per cent. South

Australia had the lowest proportion of children in

relative/kinship care (16 per cent).[270]

3.12

Kinship care is often used by Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander communities to meet specific needs and fulfil cultural

obligations. The special needs of indigenous children and young people are

recognised in the Aboriginal Child Placement Principle which outlines the placement

preferences for indigenous children when they are placed outside their family.

Preference is given to placement with the child's extended family (which

includes indigenous and non-indigenous relatives/kin); within the child's

indigenous community; and finally, with other indigenous people. This principle

has been adopted by all Australian jurisdictions either in legislation or

policy. For example, in Queensland

the Principle is contained in section 83 of the Child Protection Act. The

proportion of indigenous children in out-of-home care at 30 June 2004 placed in accordance with the

principle ranged from 81 per cent in Western

Australia to 40.4 per cent in Tasmania.[271] In Queensland,

over 60 per cent of indigenous children were placed in accordance with the

principle and the Crime and Misconduct Commission (CMC) inquiry recommended

that the compliance with the principle be periodically audited and reported on

by the new Child Guardian.[272]

3.13

Residential care is the less preferred option for

out-of-home care. However, the Victorian Department of Human Services noted:

...it may not be possible to place children and young people in

home-based care, either because they display a significant level of challenging

behaviour and/or because they are part of a large sibling group. Hence, the

objective of residential care is to provide temporary, short or long term

accommodation to children and young people who are unable to be placed in

home-based care.[273]

3.14

Children may be placed in out-of-home care for short,

medium or long-term periods or permanently. Some children are placed in

out-of-home care under respite arrangements or shared care (the care is shared

between the family and another party). The AIHW noted that not all

jurisdictions can identify which children in out-of-home care are in respite

care. Children may also be placed in respite care while being placed with a

foster carer.[274]

Conduct of out-of-home care

3.15

State and Territory Governments are responsible for

funding out-of-home care. However, jurisdictions differ in the way the services

are provided with some relying solely on non-government organisations to

provide services and in other jurisdictions there is a mix of government and

non-government providers.

3.16

In Queensland

for example, out-of-home placements are organised by the Department of Child

Safety (previously the Department of Families) directly, or through a shared

family care agency on behalf of the Department. Placements for children with

complex psychological and behavioural problems may also be organised through

one of the agencies listed on the Department's register of preferred providers

of placement and support for children with complex needs.

3.17

Foster carers in Queensland

are a person to whom the Department has issued a certificate of approval as an

approved foster carer. The Department may also place the child with 'relative

carers' or 'limited approval carers'. A limited approval carer is a person who

has not been fully assessed or trained but is approved to care for a particular

child or young person, for a specific purpose, for a defined period of time.[275]

3.18

In Victoria, the report on current home-based care has

noted that Victorian 'home-based care comprises a complex set of arrangements

that involves a number of different stakeholders including the Department of

Human Services and its case (child protection) workers, CSOs [community service

organisations], caregivers and the client themselves'.[276]

3.19

Most home-based care in Victoria

is provided by CSOs which are responsible for assessment of referrals;

caregiver management; pre-placement planning; care management; placement

management; and post placement support. A service agreement contract between

the Department of Human Services and the various CSOs specifies the terms and

conditions under which the Department purchases services from CSOs and CSOs

deliver these services. CSOs receive an annualised unit price for negotiated annual

placement targets.

3.20

Most caregivers looking after children in Victoria

have a direct relationship with CSOs through the agency's management

arrangements and an arm's length relationship with a departmental case worker.

The Department retains direct responsibility for recruiting and supervising

kinship carers and establishing placements. The Department noted that despite moves

in the 1990s to outsource the provision of all foster care, 'the shift to

kinship care, and to a lesser extent permanent care, has meant that the

department again has a significant service provision role, with nearly half of

all home-based care placements provided by the Government'.[277]

3.21

The NSW Commission for Children and Young People noted

some potential difficulties with the use of service providers:

Purchasing service outcomes can pose challenges for funders. It

is difficult to implement in geographic or cultural communities where there is

only one agency available to provide the required essential service. If that

agency is unable to achieve the outcomes purchased, the funder has no option

but to continue funding the agency.

An unintended by-product of the tender process can be disruption

and distress to children and young people as a result of changing service

providers after an initial 'pilot' period or if the funder is dissatisfied with

the service provision and services are re-tendered.

In addition, while there may be a set of high level 'service

standards' funded agencies are required to comply with, funding may not enable

agencies to adequately meet their 'duty of care' to the children, young people

and families receiving services.[278]

Numbers and characteristics of

children in out-of-home care

3.22

The AIHW in producing data on out-of-home care has noted

differences between the States and Territories in the scope and coverage of the

data. For example, Victorian data includes children on permanent care orders as

the State makes an ongoing financial contribution for the care of these

children.[279]

3.23

The AIHW reported that trends in out-of-home care have

shown increasing numbers of children using these services. At 30 June 2004, there were 21 795

children in out-of-home care compared with 20 297 children at 30 June 2003. The number of children

in out-of-home care increased by 56 per cent between June 1996 and June 2004. The

AIHW noted that the number of children in out-of-home care increased in all

jurisdictions over this period with the exception of Tasmania.

The data for Tasmania no longer

includes a significant number of children who live with relatives under

informal care arrangements made with their parents. The AIHW stated that 'taking

these children into account, Tasmania

also experienced an increase in the number of children in out-of-home care'.[280]

3.24

There were 4.5 children per 1000 aged 0-17 years in

out-of-home care in Australia

at 30 June 2004. This is an

increase since 1997 when 3.0 children per 1000 were in out-of-home care. Over

the period the largest increases were experienced in NSW where rates increased

from 3.4 to 5.7 per 1000 children and in the Northern

Territory where they increased from 1.9 to 4.3. Figure

3.2 indicates the rates for each State and Territory at 30 June 2004. The AIHW stated that the reasons

for the variations across the jurisdictions 'are likely to include differences

in the policies and practices of community services departments in relation to

out-of-home care, as well as variations in the availability of appropriate care

options for children who are regarded as being in need of this service'.[281]

Figure 3.2: Rate of

children (per 1000) in out-of-home care in Australian States/Territories at 30 June

2004

Source:

AIHW, Child

protection Australia 2003-04, Child Welfare Series no.36 (2005).

3.25

In evidence, the Western Australian Department for

Community Development also noted the increase in the number of children

entering out-of-home care and that children are entering at a younger age.[282] The Department stated:

...we are still seeing an increasing trend of children and young

people coming into care. The number of young people and children coming into

care increased by about eight per cent in the last financial year and eight per

cent in the previous year. In fact the increasing number of children coming

into care has been an issue that Treasury has raised with us.[283]

3.26

The AIHW reported the following characteristics of

children in out-of-home care at 30

June 2004:

- most (94 per cent) in out-of-home care were in

home-based care;

- 4 per cent were in residential care

Australia-wide, ranging from 1 per cent in Queensland to 9 per cent in Victoria;

- 1 per cent were in independent living

arrangements;

- of those in home-based care, 53 per cent were in

foster care; 40 per cent in relative/kinship care and 1 per cent in some other

type of home-based care;

- 23 per cent of the children in out-of-home care

were aged under 5 years, 31 per cent were aged 5-9 years, 33 per cent were

aged 10-14 years and 13 per cent were aged 15-17 years; and

- children in residential care were considerably

older than children in home-based care.[284]

Figure 3.3: Children

in out-of-home care – type of placement as of 30 June 2004

Source: AIHW, Child protection Australia 2003-04, Child Welfare Series no.36 (2005).

3.27

The Victorian report, Public Parenting, also provided information on trends in

out-of-home care within that State. Between 1997-98 and 2001-02 there was a

shift in placements towards kinship and permanent care (with growth rates of 55

per cent and 79 per cent respectively), and to a lesser extent, residential care

(an increase of 17 per cent) and away from foster care. While foster care

remains the leading form of out-of-home care, the number of clients fell by 15

per cent.[285]

3.28

The length of time that a child stays in out-of-home

care varies. The CREATE Foundation commented that while many children coming

into care are aged under five years, they tend to stay in care for short

periods before a return to their families, and may 'bounce in and out of the

system' for quite a period.[286] The AIHW

reported that at 30 June 2004

in most jurisdictions, at least half of the children had been in out-home-care

for less than 2 years. However, a relatively high proportion of children

had been in out-of-home care for five years or more, ranging from five per cent

in Tasmania to 34 per cent in Western

Australia.[287]

3.29

Across Australia,

indigenous children are six times more likely to be in out-of-home care than non-indigenous

children. In Victoria,

the rate of indigenous children in out-of-home care was 13 times the rate of

other children and in New South Wales

it was nine times the rate at 30 June

2004.[288] The Human Rights

and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) has indicated that:

The intergenerational effects of previous separations from

family and culture, poor socioeconomic status and cultural differences in

child-rearing practices are important reasons for this over-representation.[289]

Reasons why children enter

out-of-home care

3.30

As noted in chapter 3 of Forgotten Australians, over the years children and young people were

placed in out-of-home care for many reasons such as family dislocation from

domestic violence, divorce or mental illness; lack of assistance to single

parents; parents' inability to cope with their children; or as 'status

offenders'.

3.31

A Commonwealth study from the late 1970s identified

family finances, parental abuse or neglect of children, and children's

behavioural problems as factors which contributed to child welfare agencies'

decisions to place children in residential care.[290] From the 1970s, Australia

experienced significant social and economic changes leading to major changes in

families that are likely to have had different impacts on the need for

substitute care. The size of families in Australia

decreased, the number of births to teenage mothers decreased, women's roles in

families changed as more women entered the workforce, the number of one-parent

families increased and unemployment increased. At the same time, the

Commonwealth Government markedly increased its assistance to low-income

families and implemented new forms of assistance such as the supporting

mother's benefit to assist families in need.[291]

3.32

Nowadays however, welfare services' intervention to

remove children from their families 'is most likely to be due to allegations of

child abuse and neglect or harm to a child, rather than solely because of family

poverty as in earlier years'.[292]

Anglicare voiced alarm at 'the growing number of Australian children who

experience abuse at the hands of their family members at home'.[293] Catholic Welfare Australia

also stated:

There are occasions when the removal of Australian children from

their families may be warranted as part of a social welfare intervention

initiated by the state in an effort to look after the best interests of

individual children.[294]

3.33

According to the report, Public Parenting, 'in 2001-02, almost all children and young people

entering foster care had a history of protective involvement, which means that

the majority would have experienced some form of abuse or neglect'.[295] The AIHW has reported that the rise

in the number of children in care since 1998 'is consistent with the higher

number of child protection notifications that occurred in most jurisdictions

during the same period'.[296]

3.34

Drug and alcohol abuse among parents of children who

enter the out-of-home care system is endemic and is a critical issue

confronting child protection services. Victorian Government figures have shown a

significant increase since 1997-98 of substance abuse among the parents of

children and young people entering foster care.[297] It has also been shown that drug

abuse increases the risk of child abuse and neglect; figures from the 2002 NSW

Department of Community Services (DoCS) annual report reveal that up to 80 per

cent of all child abuse reports investigated by DoCS have concerns about drug

and alcohol-affected parenting.[298]

3.35

Evidence from the WA Department for Community

Development stated that its research indicated that 'approximately 70 per cent

of care and protection applications result from parental drug and alcohol abuse

in combination with other factors such as family violence and mental illness'.[299] Not surprisingly, the associated

lifestyle of drug-using parents may also make the home physically unsafe and

reduce the likelihood of parents' availability to care for young children, lead

to isolation from an extended family and expose the children to a wide network

of drug using adults.[300]

3.36

Evidence also showed the cyclical nature of out-of-home

care in families, as one care leaver advised:

The really interesting thing is that this goes in cycles. The

photo on the left is of my grandmother. She also grew up in an institution. My

mother grew up in an institution. I will share with you part of her life,

because her life was so much a part of my life.[301]

3.37

To some extent, the above sentiments about inter-generational

care were confirmed by the CREATE Foundation:

It is a bit of a gut feeling: there is not a whole lot of

research...one-third of the young mums being tracked have had their children go

into the care system in the five years since they left care. Obviously there

are some strong correlations there. That was just the tracking of a group that

left care in one year in New South Wales...there are some services in Western

Sydney that say that they are seeing their third generation of people who have

been in care. I think there is a link there but, especially without a lot of

research, I would never like to push that there is an intergenerational care

cycle, because young parents and older parents who have been in care certainly

do rise above it and do not go on to abuse and neglect their children.[302]

3.38

While family poverty may be less of a reason for

welfare services' intervention regarding children nowadays than in previous

eras, the majority of children in the care and protection system are from low

socio-economic families.[303] Evidence

to the Committee's 2004 inquiry into poverty and financial hardship showed

overwhelmingly that economic and social stress can lead parents to become less

nurturing and rejecting of their children and that children living in poverty

have a high incidence of abuse and neglect.[304]

Similar evidence has been presented to this inquiry and UnitingCare

Burnside confirmed the link between poverty

and associated problems and the placement of children in care:

Poorer parents get less relief from the constancy of child

rearing. They are less able to afford baby-sitting, quality childcare,

entertainment, social or sporting activities or go on stress-relieving

holidays. They tend to experience higher levels of conflict and family

disruption. They are more likely to live in substandard and crowded housing

where it is difficult to get a break from other family members. Parents in

poverty are more likely to experience ill health themselves and for their

children to be ill...Under these circumstances it is understandable that some

parents have a less informed or unrealistic understanding of parenting and

children's behaviour.[305]

3.39

Therefore, many families experience an array of

problems: family poverty and impoverishment are increased by parental substance

abuse because of the high cost of maintaining a drug habit and parents

experiencing domestic violence often have substance abuse problems. Further, children

of parents with a disability or multiple disabilities, particularly an

intellectual disability and mental illness, are significantly over-represented

in the child protection system. It is more likely that parents with a

disability will have at least one child if not more removed early in life and

approximately one in six children in out-of-home care will have a parent who

has a disability. People with Disability submitted that:

...evidence provided at the NSW Legislative Council inquiry into

disability services and the inquiry into child protection services demonstrate

that when family support programs and sufficient community-based mental health

services are provided to parents with disability, the outcomes for their

children are not significantly different from other children.[306]

3.40

In some situations a range of factors may lead to complex

problems for families where greater levels of intervention are required. As a consequence,

children may remain in out-of-home care for longer periods of time. The WA

Department for Community Development stated:

The increase [in numbers of children in out-of-home care] also

relates to the complexity of family situations with issues such as drug abuse

and so forth. That is driving the numbers higher because there are a lot of

issues to be resolved before the children can leave care and be back home, as

is our aim – to reunify parents and children.[307]

3.41

It has also been reported that the prevalence of

complex problems among the families of children entering care has increased

with the Victorian Department of Human Services reporting that between 1997-98

and 2001-02:

- parents experiencing domestic violence and

substance abuse increased by 56 per cent;

- parents with a psychiatric disability and

substance abuse increased by 50 per cent; and

- parents with an alcohol problem who experience

domestic violence increased by 71 per cent.[308]

3.42

Anglicare commented that:

Expanded programs to support families effectively to ensure

their children's safety and well-being through prevention and early

intervention programs are urgently needed. There is a need for more investment

in prevention and early intervention, including family support programs.[309]

3.43

The NSW Commission for Children and Young People

commented that many services which could prevent or reduce the severity of

abuse are family support services, which are directed towards parents,

especially those with 'risk' characteristics in their family make up. Other

services targeting children with learning and social difficulties or aggressive

tendencies are ideally suitable for delivery through childcare and schools.

3.44

The Commission went on to comment that a comprehensive

outline of frameworks to constructing services to alleviate the likelihood of

abuse was provided to the Commonwealth by a team of noted researchers and

academics in 1999 in the 'Pathways to prevention – developmental and early

intervention approaches to crime in Australia'. However, the Commission took

the view that 'there are obstacles to the provision of adequate preventative,

support and remedial services in Australia'. These obstacles include a lack of

resources as 'currently whether any jurisdiction can effectively respond to the

level of abuse and child exploitation in its community is doubtful'. There is

also poor coordination and effective use of resources. The Commission noted

that 'the system currently does not appear to provide value for its investment',

concluding that:

The Commission supports the view that the states are

constitutionally responsible for the provision of statutory child protection

services. However, the provision of statutory child protection services is only

possible when they are contextualised within a range of primary and secondary

programs and where there is a vision about the outcomes the national system is

to deliver.

The Commission's view is that the Commonwealth has a valid role

in providing some services and shared leadership to achieve the outcome of an

effective child protection system.[310]

3.45

As noted previously, indigenous children as well as

other care leavers, have a high need for out-of-home care services with key

reasons including:

- inadequate housing and living conditions;

- intergenerational effects of previous

separations from family and culture;

- cultural differences in child rearing practice;

and

- a lack of access to support services.[311]

3.46

The Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander

Child Care (SNAICC) has commented that child neglect is a result of parents and

families being unable, 'but not necessarily unwilling' to provide for their

children because of family poverty, unemployment, poor housing and family

stress. SNAICC stated:

The major contributor to the over representation of Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander children in the child welfare system and out of home

care is child neglect – not child abuse. In fact an Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander child who has been removed from home is less likely to have

been abused than a non Aboriginal child.[312]

3.47

The AIHW has indicated that there is no national data

available on the reasons why children are placed in out-of-home care. However,

a new data collection is currently being developed. More information will be

collected on the child and each placement the child has throughout their time

in out-of-home care.[313]

Issues facing out-of-home care

3.48

Many submissions pointed to the issues facing

out-of-home care as a result of the increased numbers of children in care and

their more complex problems. The Committee heard evidence that the system is 'chronically

stressed' and often overwhelmed by demands. Anglicare stated that 'the chronic

state of foster care across Australia

is a major underlying cause of unsafe and inadequate treatment of children in

institutions and fostering programs'.[314]

3.49

The WA Department for Community Development expressed

the view that problems in foster care are occurring across Australia:

To be honest, we are not the only jurisdiction in Australia

facing issues around the recruitment of carers and being able to cope with the

increase in the number of children in care and finding placements for them. If

we had the answer to that question, the kids and we would be a lot better off.[315]

Systems decisions that affect children

3.50

Various respondents noted systems' inadequacies which are

working against children's interests. The Children's Welfare Association of

Victoria (CWAV) referred to a study from 1994 by Cashmore et al that described

'systems abuse' as:

...preventable harm done to children in the context of policies or

programs which are designed to provide care or protection. Such abuse may

result from what individuals do or fail to do or from the lack of suitable

policies, practices or procedures within systems or institutions.[316]

3.51

Some evidence suggested that often short-term services are

being given priority over cohesive long-term planning and quality of care.[317] The foster care system is also said

to be too reactive and not necessarily aware of the importance of keeping

siblings together:

The placement system is so attuned to responding to crisis that

finding a safe place and a bed for the children takes priority over every other

consideration. This constant state of crisis in the care system is a barrier to

the physical, emotional and mental development and wellbeing of children in

care.[318]

The separation of a child from his/her parents and surroundings

may be traumatic and the additional separation of the child from siblings,

school and social networks compounds the negative experience of care.[319]

3.52

Some witnesses cited instances relating to governments'

failure to ensure that children were safe and well cared for. The mother of a child

in foster care advised of concerns that on occasions her son has gone to school

without lunch or money and the school has had to provide him with lunch. She

made the point that the NSW Department of Community Services had not acted in

response to her complaints.[320]

3.53

Other evidence described an instance of a child being placed

at the age of six months in what turned out to be a very abusive foster care environment,

with no legal or formal arrangements between his biological and foster parents.

In describing the many difficulties which he had experienced as a child, including

being constantly starved and beaten and witnessing similar treatment towards his

foster siblings, the young man advised that he found out at the age of 12 years

that he was adopted, from a Department of Community Services social worker. He

noted too that it was only through his brother's involvement with the police

that the Department 'accidentally' discovered his origins. He has since

ascertained via freedom of information requests that the Department had had no

records on him. This lack of government involvement or monitoring has caused

him distress as outlined below:

At 19, I was forced to change my birth name...to what it is now...when

I applied for a health care card...the Government did not know who I was...The

answer I would really like to know is – how the hell could the Government not

know who I was for 10 years. Is there anybody else out there like me I wonder?

I am less than satisfied with the response I've received from the Government.

Everything I've discovered however has been from them although to this day I

have no idea how I came to be with my foster parents as a baby at six months of

age...Where is there accountability and duty of care.[321]

3.54

The NSW Commission for Children and Young People

highlighted the need to recognise the positive aspects of the current system of

child protection and out-of-home and alternative care, citing some of the system's

strengths in NSW, including:

...the Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Act

1998 is based upon principles of good

practice and key research messages;

the recent decision by DoCS to

move the organisation away from a forensic approach to child protection service

delivery to a more holistic assessments and strengths based approach is to be

applauded;

the development of specialist out-of-home care teams and of

specialist workers/cross office teams for recruitment and support of foster

carers has occurred in some areas.[322]

Input by children

3.55

The Committee considers that it is timely to ensure

that children and young people in care can participate in decisions about their

lives and agrees with the rationale of the CREATE Foundation about involving

children and young people. That organisation's research shows that children in

care are often 'left out' with many of them not being informed about matters that

affect their lives such as a changed placement or who a new case worker might

be.[323]

3.56

That children and young people need to be heard was

well expressed by various people including an ex-ward who described her circumstances

of having 'missed the boat' in parts of life particularly with her career. As a

young person she recognised her need to achieve an education and pursue a

career but was frustrated in efforts to express her needs to people who could

help her:

There was no...social worker to explain the 'care' system to me,

or what would happen, or expectations of either parties, or that I would have a

case plan drawn up etc. I was just doing time. I had no rights, no advocacy, no

representation...This attitude WAS NOT REPRESENTATIVE of society in general in the

early 1970s as much social change was occurring.[324]

3.57

While the above situation should have been anathema by

the 1970s given the prevailing social attitudes which emphasised pathways to

education and career opportunities for girls, the Committee is aware that similar

situations are still occurring. The CREATE Foundation advised the Committee

about life for some children in institutional care nowadays:

Across the care system young people are now being placed without

having had any conversation about where they would like to be placed or who

they would like to be placed with – whether in foster care, kinship care or any

other type of care. There is still a huge lack of conversation with young

people...There is a need for a real priority focus on education because the

education of far too many children and young people who have been in care has

been seriously broken up. Many of them will leave school quite early; many will

leave without year 10 or year 12 qualifications and many will leave having very

poor literacy and numeracy skills. For them to try to get back into education,

the door is often shut and there is no support to do that.[325]

3.58

The WA Department for Community Development

acknowledged that in the past 'the child has certainly not had the voice they

should have had', while parents have had active participation in conferences

and 'been respected by providing input and contributing to the decision making

process'. However, the department noted that in recent times, situations have

changed:

Children have had direct input in more recent times depending on

their age, development and understanding of the circumstances. I have

personally chaired case conferences where children as young as 10, 11 and 12

have actually participated as part of those forums.[326]

Children with high-care needs

3.59

Some children enter out-of-home care with high-care and

complex needs usually because of very damaging situations and experiences in

their lives, prior to care. Often it can be difficult for these children to

adapt to everyday foster care and they require attention and monitoring that

can only be provided in specialised, residential care by people who are

equipped to care for them:

Some of these kids are too damaged to slot into another family

without extra professional supports, like psychiatric evaluation and treatment,

physical rehabilitation and educational assistance. [327]

3.60

Some organisations described the extreme damage of many

young people and the people and specialist services that are required to care for

them:

...[they are] often so damaged by their experiences of life and

the care system, that their lack of trust of all adults makes the task of

engaging, educating and helping them to begin to turn their lives around

difficult and sometimes almost impossible.[328]

...difficult, if not impossible, to care for [them] within the

foster care system as it is currently set up. There should be perhaps a

consideration of the professional foster care model.[329]

...The sort of person who could do respite foster care once a

fortnight is quite different from somebody who would take on what could almost

be a lifetime commitment of a relationship with a high-risk adolescent who is a

very damaged person...You cannot put a range of young people who have quite

complex needs and issues...together in the community and expect that they will

just meld in.[330]

3.61

One very experienced carer who has five children of her

own and who has cared for over 30 foster children submitted details of the lack

of support from the South Australian Department of Family and Youth Services (FAYS)

when she had responsibility for 'the most difficult child I ever met'. She

noted that FAYS' staff were 'out of touch' and inadequately

educated for the reality of caring for severely damaged children.[331]

3.62

The Committee was provided with examples where, from

very early ages, children's lives were interspersed with traumatic and

unsettling experiences which led to them becoming very hard to handle and

costly to keep in care. For example, 'Kim' was

placed in care on the day of her birth, remaining so until she turned 18 years.

She experienced many residential arrangements and harsh rules, lived with

paedophiles, sustained injuries in care, had no significant and consistent

adults in her life, and when a cottage closed down, she was forced out and

shunted elsewhere. Little wonder that she became a high-risk child requiring

around-the-clock care:

I got placed in a house and have one worker around the clock two

days on and two days off. Got along really well with them...We sat down and made

our own rules and I felt human when I was there. It cost about $10,000 a month

and I spent about 6 months there.[332]

3.63

Another 'high-risk' child was allegedly raped, on a

daily basis by his father and uncle. He says he was often taped up when this

happened, regularly beaten and kept in the laundry at night:

By the time he was five, he'd been through six foster families.

Then, he got lucky. He was placed with a woman who was prepared to change her

whole life to allow him to have one of his own.[333]

3.64

Evidence to the Committee highlighted that the provision

of care for high-risk children is hampered by difficulties in obtaining

suitable carers as well as the spin-off of financial cuts:

At the moment in Victoria

we are suffering productivity cuts, which will limit these self-funded

operations that we do which are already necessary. It is a very difficult

situation.[334]

...I think it then becomes unreasonable to expect someone who is

in essence a volunteer to be a full-time carer, 24 hours a day, seven days a

week, on simply a reimbursement basis. But it does move the notion, the idea,

of foster care into another dimension.[335]

High costs of care for children

with emotional or behavioural problems

3.65

The cost of maintaining a high-risk adolescent in

residential care is expensive and more than one welfare organisation cited

examples. Anglicare stated 'for us to run a high-risk adolescent unit for four

young people aged 12 to 17 costs us about $230 000 per adolescent'.[336]

3.66

Figures on children requiring high levels of care show

that when it is necessary to accommodate such children and young people in

motels with several full-time workers, it can cost up to $100 000-$300 000

per year per child.[337]

3.67

Care requirements for young people who are at the

'extreme end of this difficult group' can involve expensive options of 'containment'

or 'lockdown':

In New South Wales,

some 400 'high-risk' children cost the Department of Community Services about

$60 million a year. A recent DoCS 'snapshot' indicates 182 kids are costing

more then $250 000 each a year, the highest coming in at $858 000.[338]

3.68

One highly-traumatised 15-year-old girl with a record

of displaying violent behaviour is said to require six carers to ensure that

she does not harm herself or other people:

At one stage this difficult arrangement of care, involving at

least six workers on shifts around the clock, was costing more than $15 000

a week; in fact he describes her as 'the million dollar kid'.[339]

Abuse and treatment of children in

foster care

3.69

The Committee received significant information and

stories about abuse of children in foster care, not dissimilar to themes

outlined about the bigger institutions and orphanages in Forgotten Australians. CBERSS made the point that:

...we not only catastrophically removed kids from families but we

subsequently punished them more...we are still doing it today. We are still

removing kids from families. We may not put them in institutional care – we

might put them in foster care and they go around and around – but the abuse

continues.[340]

3.70

The theme that abuse continues and that the state has

neglected its duty of care towards children in its care is reflected often: 'if

the state was a birth parent, on many occasions the children would be removed'.[341]

3.71

Dr Maria Harries cited United States research showing

that 50 per cent of children in foster care have been sexually abused as well

as statistics showing that one in three to one in five children have been

abused yet they have not lived in institutional care. CBERSS noted that figures

are likely to under estimate the prevalence of child sex abuse given that

victims often do not report abuse because they fear negative consequences from

disclosure.[342]

3.72

The Committee was advised that contemporary situations

are such that children are not necessarily safe in care, as the CREATE

Foundation noted:

We would also argue and recommend that there is vigorous

recruitment of people who work within institutional care and residential care

type places. The feedback we have had from young people is that the staff there

are not always professional in their manner of dealing with children and young

people.[343]

3.73

As well, a number of young people related stories of

harsh conditions in care in recent times including the following examples:

[There were] fights, harsh discipline towards the kids around me

from the supervisors that were there and low living standards.

People getting hit with towels and wooden spoons and things like

that, pretty much right in front of me. There would be someone at your table

mucking up and a supervisor would come out of nowhere and slam on the table,

and plates and everything would bounce up.[344]

3.74

The WA Department for Community Development

acknowledged that various abuse allegations had been raised with it through

children's advocacy groups such as: Watchmen In God's Service; Advocates for

Survivors of Child Abuse; Help All Little Ones; the Juvenile Justice

Association and the Family Support for Victims of Paedophiles. The Department

raises such concerns with the State Police.[345]

3.75

Sexual abuse in foster care featured in many

submissions though much of it related to earlier days. Descriptions of abuse in

evidence included situations of wives being complicit where their husbands

sexually abused foster children; government departments not acting to remedy

bad situations; good care becoming bad, and of children being abused over long

periods of time; and situations of humiliation where a child was treated like

an animal for 10-years and locked in kennels where he had to pilfer dog food to

survive, while another child was locked in a pitch-black garden shed with

spiders and mice and had to wear a nappy with a dummy in her mouth and parade

in front of children on the school bus.[346]

3.76

A common theme in evidence was that any outside

perceptions of abuse in the foster home would have been anathema, where from

the outside everything seemed to be stable, often in very good 'Christian'

homes. One former foster child outlined details of her life in the 'apparently

perfect placement' in a leafy Sydney

suburb. In reality, she was sexually, emotionally and physically abused for

years. Another person described her 'lucky' situation of 14 years 'stable'

care, where she and her sister appeared to be happy when in fact they were

isolated, lonely and terrified of a very controlling foster mother.[347]

3.77

As with children who experienced slave labour in institutions,

many outlines were given about the use of child slave labour by foster parents,

regardless of the era or the location. Often children were required to

undertake some unusual tasks, along with the drudgery of housework and domestic

work:

If they had a party you had to stay up and clean up and be up

early and look after their children and keep them quiet till they got up...I used

to eat the left overs...I didn't want to go to Perisher Valley as their friends

used to come with their family and doing the washing under the house was cold.[348]

3.78

Some people have described situations of being treated

differently, working hard and receiving no love or family nurturing and

affection, or being isolated, both in the home and from other children at

school; and having excessively disciplinarian and inflexible dominating foster

parents.[349] One former foster child

told of her loss of identity when her foster mother made the decision to change

her name:

...I asked her not to change my name because that is all that I

own. It belongs to me. But like everybody else she did not listen either and

changed that to Rosemarie. But my name is Marie

Rose. Nobody ever listened they just did

whatever they wanted.[350]

3.79

The Committee also received positive stories as the

following excerpts show:

...I believe that my foster care experience was a positive one; I

was taken well care of and was treated like their natural child. My placement

broke down as a result of my need to establish myself as a young adult.[351]

...I went through quite a few public schools until I was placed at

a foster home. I am probably one of the luckiest people you will ever hear

about. It was a great home for me and I was there for eight years. I had a

great relationship and I still talk to them now.[352]

3.80

As well, some people described contrasting experiences

of foster homes:

We were then sent to Mrs Ingham's

place at Bendigo. I don't think we

could have found a better home. She was a great church woman and lived her

religion...She looked after us better than our own mother...We were then sent to a

woman a Mrs Bramley...The verandah, a cellar under the house and the backyard

were our home and we could sleep in the bedroom at night. In the cold weather

we were always cold and hungry...half starved and eaten by bed bugs. We were sent

to school with our head full of lice.[353]

3.81

Another person described one of her foster care

experiences as her 'first real family' and the 'happiest time of my young life'

which contrasted markedly with her later foster care where she was subjected to

horrific sexual abuse.[354]

Multiple placements

3.82

The Committee heard evidence that children and young

people in out-of-home care often experience many moves in their home and school

lives. Multiple placements have serious negative effects on young people's

emotions, educational and employment chances and long-term personality

development. Unfortunately, the following excerpt from a Radio National program

is indicative of the high number of placements experienced by some children:

I remember being really surprised when you said, in fact I

thought I'd misheard you, you said you had 80 different placements, I thought I

must have misheard and you'd said 18, because 80 seems like an awfully large

number for any kid.[355]

3.83

Resultant problems from the many moves can be wide

ranging and may include experiences of ongoing depression, anxiety, anti-social

attitudes, nightmares, fear of people, and lack of confidence, social skills

and identity. MacKillop Family Services commented that multiple placements can

be unavoidable, often because it can be difficult to find suitable carers for

children and young people with complex needs.[356]

One former foster child stated that:

...by the age of six I had undergone seven failed placements, due

to the inability of the foster families to cope with a child whose needs were

so great for a loving family...I was declared unsuitable for immediate placement

and sent to the children's home.[357]

3.84

Child welfare practitioners are aware of the damaging

effects for children's development from all forms of inconsistency and

proponents of attachment theory have demonstrated that children need consistent

routines of care from one or two preferred attachment figures.[358] As well, if adults in the

out-of-home sector are to gain the trust of the children and young people and

therefore assist them, it is obvious that some semblance of stability is

required:

In one case we helped a young teenage boy in relation to

criminal matters. In the eighteen-month period before he came to us he had in

excess of twenty foster places. One pair of initial foster parents had been

keen to look after him on a more permanent basis but lost interest after the

department delayed and procrastinated in getting back to them. The boy had been

so disappointed that it was very difficult for him to trust anyone again. This...is

commonplace for young children who have been in care and protection, as they

experience what they see as betrayal.[359]

3.85

The multiple placements of children and young people in

out-of-home care is well documented. A Victorian Department of Human Services

report shows that of all clients in placement at 30 June 2001, seven per cent had had just one placement, 65 per

cent had had four or more placements and 11 per cent had 10 or more placements.

The impact of multiple placements on a developing child's behaviour and

educational attainment is substantial, often resulting in negative life patterns

including those related to instances of stealing, absconding and bullying.

Severe learning disorders can be a by-product of constant changes in a child's

carer. This can affect a young person's academic performance which of course is

compounded by constant changes in schools. A 1996 NSW study demonstrated that

80 per cent of children who lived at home with their families completed their

Higher School Certificate compared with 36 per cent of young people in

out-of-home care. The average number of schools attended by young people living

at home with their families was 2.3 compared with 5.4 schools for those in

out-of-home care.[360]

3.86

A 23-year-old man who had been moved around by DoCS 'every

three months – here, there and everywhere', described to the Committee, his

situation of not ever having been to school and being unable to read and write,

having difficulties in relating to people, never having had a job and being

unsure of what he wanted. He advised that if given the opportunity, he would

like to learn literacy and numeracy skills but felt unconfident that any employer

would give him a job.[361] Another young

man aged 22 years who had also experienced many institutional placements, told

the Committee that although he had done well at school, he had very little

confidence and was experiencing difficulties in gaining meaningful employment.

He considered that finding decent employment would be a key to assisting him:

I actually did all right in school. I did not finish year 12 but

I finished year 11. I was quite gifted in a couple of subjects...help with

employment is the main thing. I need something behind me like a trade or

anything like that. I have nothing.[362]

3.87

Professor Dorothy

Scott emphasised that the multiple

placements of today's system can be more damaging than the relative stability

which some children and young people may have experienced in the old-type

institutions.[363] The Post Adoption

Resource Centre-Benevolent Society stated that many past mistakes in policies

and practices in the out-of-home care sector have not necessarily served as

lessons for contemporary policymakers:

...we continue to over burden and underpay those working in child

protection and out-of-home care, causing high staff turnover. Similarly, we

invest large sums of money into problematic 'time-saving' strategies such as

the DCS Helpline and into child protection, which works on short-term goals and

is crisis-driven, and fails to provide children with long-term futures. Time,

money and effort should be invested into supporting existing and coming foster

care placements to give children a better chance of stability and continuity.[364]

3.88

Adding to problems for children in out-of-home care can

be the lack of consistency with departmental caseworkers, usually the result of

a high turnover in workers. A 2002 CREATE Foundation survey of 143 children and

young people aged nine-18 years across Australia, found that 80 per cent of the

children and young people surveyed had a departmental caseworker, six per cent

were unsure if they had one and 14 per cent did not have one. Of the children

and young people who had a caseworker, 32 per cent had had more than five

workers while in care, 23 per cent said that they had the same caseworker for

three months or less and only 10 per cent had had the same departmental worker

since being in care. CREATE advised that the significant change in caseworker

numbers impacts negatively on their capacity to meet the needs of children and

young people in care. One young person noted:

I found [it] didn't work having so many case managers in such a

short period of time. [More than 5 in less than two years]. They never seemed

to respond to what I wanted, they didn't organise contact with my brothers. Since

I have had a stable case manager in the last few weeks it has been a lot better

because she has established contact with me and my brothers.[365]

3.89

The Committee recognises the complexity of the issue of

multiple placements which is symptomatic of a range of problems for families

including drug and substance addiction, unemployment and family breakdown,

which often lead to situations of children being placed into out-of-home care. At

times the anti-social behaviour of some children who have experienced abuse and

spent too long in abusive situations, escalates to a point where no carer is

able to provide care for them. In this context, Youth Off The Streets advised:

So young people are inappropriately placed. When they are

placed, there are insufficient resources on the ground to support those

placements. You can predict from that point onwards that inevitably they will

rotate in and out of foster care placements until they are deemed

'unfosterable'. Then, when they are teenagers, we see the result. Some may come

to us...Others end up on the streets as a result of the systems failure that they

have experienced throughout their care history.[366]

3.90

Therefore, a multi-faceted problem develops which can

only be addressed by a comprehensive multi-faceted response. Initiatives which

can be successful to address problems include early intervention programs to

assist people with their parenting and caring abilities. As well, other areas

that need to be addressed are those to engage more foster carers and to provide

them with support and also ensuring that children have access to education and

worthwhile employment.

Indigenous

children

3.91

Indigenous children are over represented in out-of-home

care. As well, systems breakdowns seem to be occurring regarding indigenous

children's placements. As mentioned, all jurisdictions have adopted the

Aboriginal Child Placement Principle regarding preferred placements of

indigenous children.

3.92

The Law Society of New South Wales submitted that there

is frequent failure to give proper effect to the principle. In particular, Aboriginal

or Torres Strait Islander children are not being identified as required by

legislation; indigenous children are not being placed in culturally-appropriate

out-of-home care; and no consultations are occurring with the welfare or

indigenous community groups that could assist in identifying suitable

placements. The Law Society stated:

...there is typically no real attempt to allow the child to

develop any understanding of the child's heritage and culture. Any plans

proposed by the Department are espoused in a general way and non-specific in

their services. There is frequently a reliance upon the foster carer doing the

right thing without any commitment by the Department and its Officers to ensure

the heritage and culture needs are followed through...indigenous siblings are

separated, sometimes into indigenous appropriate placements and sometimes not.

There is frequently a failure to provide regular contact not only between the

siblings but with their extended family members...That failure is both in breach

of the principles referred to and the objects of the Act which require a child

to know and develop a relationship with the child's family and in the wider

sense his or her community.[367]

3.93

SNAICC stated that:

...the continuing practice of placing children with non Indigenous

foster care constitutes a serious risk to the cultural identity of Indigenous

children in Australia.

In particular it places at risk their right to grow up in a community with

other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, profess and practice

their own religion and use their own language.[368]

3.94

Families Australia

noted that while kinship care is very important to indigenous people for

indigenous children needing out-of-home care, a serious shortage of indigenous

carers is part of the reason why the Aboriginal Placement Principle is often

not adhered to.[369]

3.95

In response to the high number of indigenous children

in care, SNAICC has recommended a national commitment to Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander children including:

- the development of a National Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Family policy between indigenous organisations, the

Commonwealth and State and Territory Governments to reduce the number of

indigenous children being removed from home for child protection and poverty

related reasons; an expansion of the availability of Aboriginal and Islander

Child Care Agencies and Family Support Services; and an outline of targets for

reducing the current rates of child removal;

- the provision of improved access to family

support services to prevent family breakdowns and reduce the number of

indigenous children removed from their families by welfare authorities; and

- the implementation of recommendations from the Bringing them home inquiry, including

those related to the reform of the currents systems of child protection and

minimum standards of care, protection and support for Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander children in need of care.[370]

Children returning from out-of-home

care to abusive situations

3.96

The primary goal of out-of-home programs is to reunify

children and young people with their families, where this is in the best

interests of the children. However, with children being placed in out-of-home

care as a consequence of complex family problems, including parental substance abuse,

difficulties can be encountered in ensuring that children are returned to

suitable family situations.

3.97

The Committee received evidence about children being

returned from out-of-home care to abusive family homes, including instances where

parents are on drugs. Many care organisations acknowledge parents' rights to

request the return of their children but they highlighted the difficulties

associated both with assessing parents' suitability and being able to monitor

such situations. The CREATE Foundation stated:

If we say that, yes, the parent has to undertake a drug program,

we do not then go thoroughly enough into making sure that they have undertaken

that program, that they are clean and that these children are going to be safe

when they return to that home. And then, once they are back in that home, there

is no monitoring in the home to make sure that everything is going well and

there are no alarming characteristics.[371]

3.98

A parent with extensive experience of providing foster

care cited her first-hand experiences of returning a child to a home where he

would be exposed to abuse:

...it is very hard...to have to send the child back to a situation

that you know the child does not want to return to, that you know is going to

be detrimental and where the child is probably going to end up back in your

care...this little boy's mum was given additional access time with him,

unsupervised, when it was patently obvious – and everybody knows – she was

abusing again.[372]

3.99

The difficulties of reunification are reflected in data

reported by the Victorian Department of Human Services. It was found that there

was a fairly high level of attempt at reunification with parents over a

five-year period. However, it was estimated that of children who enter

home-based care, 'only between about 20-30 per cent will be successfully

reunited with their parents over a five-year period'.[373] The WA Department for Community

Development noted that while a return to families is preferred, the Department

recognises that some children and young people will never return home due to

unresolved safety concerns at home. The department noted:

Repeated attempts at family preservation has meant some children

and young people experiencing frequent placement changes and broken

relationships as they move between parents and carers.[374]

3.100

The Committee heard that the parents and family members

of children in care are often marginalised or disempowered and that

insufficient attention and resources are given to ameliorating the damage to

children or to addressing the behaviour or parents' attitudes that led to their

children being placed in care. Mercy Community Services argued that governments

need to provide more services for behavioural and attitudinal problems to

ensure that parents are able to have their children returned at the earliest

and safest opportunity.[375]

3.101

Some organisations have called for funding to help keep

children with their families via intensive support services, and to ensure that

a child's removal from their family is in accord with permanency planning so

that the child is given opportunities to maintain contact and relationships

with significant members of their family, particularly with their siblings.

This is crucial in assisting children to develop a sense of stability and

identity.[376]

Children and young people leaving

foster or out-of-home care

3.102

Each year, about 1700 Australians aged 15-17 years are

discharged from out-of-home care. Some return to the family home, others exit

care into independent living.[377] They

are one of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged groups in society, yet, often they

do not receive support to help them to settle their lives or to find

accommodation and employment. Of particular concern is that many children and

young people enter out-of-home care with myriad problems and many depart the

system with additional problems. It seems to be a continuum of difficulties for

them.

3.103

Young care leavers face barriers in accessing

educational, employment and other developmental and transitional opportunities.

As mentioned earlier, many could have experienced abuse and have had many

changes in carers, placements and schools and have no real assistance networks

as they move to independence.

3.104

As the following excerpt shows, some young people have

experienced abusive and unstable foster care conditions from which they often carry

'scars' for life:

At age 14 after leaving home for the 3rd time and

just not wanting to get hit anymore, I was 5 foot tall, wore size 6 kids

clothes and weighed just 5 stone. For the next 2 years, I was thrust between

foster family and any old place the department could place me in including

brief periods with juvenile offenders although I had done no wrong...I returned

home to my foster parents at 16 years of age for 18 months before being thrown

out of home in the middle of repeating year 12. A week later whilst I returned

to pick up my clothes, my foster mother threw the adoption papers in the bin.

This was just devastating and an action I can never forgive. I meant nothing to

my foster parents and they made it seem like it was somehow my fault...The abuse

that I suffered at the hands of my foster parents during my childhood has

scarred me for life...Fortunately I was never sexually abused, but my foster

mother was the best teacher in selfishness and deprivation...the pain will not go

away. I have absorbed myself in tasks to hide the pain. Later in life I will

have to deal with it, somehow and some day.[378]

3.105

The NSW Committee on Adoption and Permanent Care also

noted that often young people leave care with enormous emotional and

psychological baggage.[379] They may

have nowhere to live. Often their many years in refuges and lack of social

skills means that they are blacklisted from the private rental market, and

community and departmental housing waiting lists are often very long.[380] The 1996 NSW study of wards leaving

care in that State found that one year after leaving care, most participants

had unstable living arrangements and half were unemployed and had financial

troubles.[381]

3.106

A care leaver from the 1970s who endured difficulties, even

though it was easier in those days to find employment, described the situation now

for care leavers:

...many young people are leaving care, without finishing high

school, and without any training scheme for employment. They are effectively