Chapter 2 - Contemporary framework for child protection - Structure, services and processes

While some would argue that Australia's

current child welfare system presents a marked attitudinal shift away from the

Dickensian child care policies practised earlier this century, others could

argue that nothing has changed from our colonial days where control and

authority over children and families was the order of the day. There are a

number of Australian child welfare and social policy analysts who have argued the

history of state intervention in the area of child welfare has been one of

control rather than the provision of assistance that might be in the bests

interests of the child or his/her family.[73]

Australian society is already experiencing...an increasingly numerous

'underclass' with entrenched inter-generational deprivation and lack of social

progress; an increasingly marginalised, disempowered subset of the community...this

group is increasingly able to interact only with each other...the greatest cost

to us as a broad community, is the untapped potential of these children and

adults who are trapped in an environment where their talents, skills and

abilities will not see the light of day except through exceptional effort and

struggle.[74]

Introduction

2.1

As outlined in other chapters, the Committee heard evidence

about many child welfare issues across Australia,

much of it painting a dismal picture about child abuse in out-of-home care and

institutions for children with disabilities and juvenile detention centres. Evidence

related to many issues, including the unavailability of national data on child

abuse; calls for national legislation for the care and protection of children;

and the increasing number of children and young people from indigenous

backgrounds and with disabilities who are being placed in juvenile justice

centres.

2.2

This chapter considers the framework and processes of Australia's

child protection system that entails the interaction of different laws and

legal systems, not only between the federal arena and the States and

Territories, but also among the States and Territories. As such, the Committee

has considered aspects of the Commonwealth's Family Law Act 1975 (FLA)

and the relevant State and Territory child protection Acts.

2.3

The States and Territories each have a range of

agencies which work to protect children, though their functions vary. Some bodies

have investigatory powers while others take on advocacy and coordination roles.[75] Some jurisdictions have children's

commissioners and/or officials such as children's advocates or guardians and

their responsibilities differ. As with other areas of service delivery in Australia,

many programs to assist children and young people in need of care are

administered by State-Territory and Commonwealth Governments, often with

assistance from non-government agencies. It can be difficult to determine which

sector or service provider has responsibility for some programs, irrespective

of the jurisdiction. Overall, Australia's

child welfare system has been described as:

...fragmented by numerous jurisdictions and a variety of

responsible bodies. This often leads to less-than-ideal results for children

where there are multiple agencies involved in their life with little

coordination between them. The system is so disorganised at times that agencies

can attempt to pass responsibility to others so as to minimise their workload,

without cognisance of the impact on children and families.[76]

Legal and government framework for child protection

2.4

In 1997, the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) noted

over 230 pieces of Commonwealth, State and Territory legislation in Australia

to deal with issues for children, with their administration beset by policy inconsistencies

and duplication and gaps in services. The ALRC wrote that the division of

responsibilities between different levels of government and departments within

each level of government ensues in children and families often having to negotiate

a complex web of agencies when they come into contact with legal processes.[77]

Commonwealth's role in child

protection

Family Law

2.5

Under Australia's

constitutional arrangements, the Commonwealth has a role in protecting children

under the Family Law Act 1975 (FLA)

(the principal Act dealing with legal aspects of Australia's

family law system). Part VII of the Act focuses on children, children's 'best

interests', parental responsibility, and children's right to know and be cared

for by both parents and have regular contact with both parents and any other

person significant to their care, welfare and development, unless it is

contrary to the child's best interests. Under the FLA

the Commonwealth's substantial role in child protection arises through cases in

Australia's

Family Court and the Federal Magistrates Service (which deals with less complex

cases) under the FLA. Family law cases in Western

Australia are dealt with under an independent State-based

Family Court which was established in 1976 under the Family Court Act and which mirrors the FLA.[78]

2.6

The example below shows how the workings and responsibilities

of the Family Court and the State and Territory child protection agencies can

result in situations where children may be left unprotected, particularly

regarding child abuse allegations.

2.7

Specifically, overlaps can occur in responsibility for

some child protection matters between the State and Territory children's courts

and the Family Court or Federal Magistrates Service. This can be particularly

serious given that despite a quarter of the cases before the Family Court

involve child abuse claims, that court has no independent power to investigate

such allegations, and, less than 10 per cent of the allegations transpire to be

false.[79] While FLA

provisions require that child abuse reports be made to the relevant State or

Territory child protection authority, at times further action is not taken for

reasons that include variances between some State and Territory legislation and

the FLA regarding contact orders

and other issues. As well, FLA

definitions of 'abuse' are wide and may not be considered to be of the utmost

seriousness or necessarily reportable under State or Territory legislation.[80]

2.8

The NSW Commission for Children and Young People raised

an issue of concern, noting that the adversarial nature of many family law

cases can result in a downplaying by State and Territory representatives of

accusations of abuse of children in Family Court disputes.[81] Therefore, a potential exists for

children to be returned to unsuitable or unsafe circumstances because abuse

allegations raised in family law proceedings are not followed up by a State

child protection authority. It has been argued that the adversarial nature of

many family law cases may reflect the often effective use by defence lawyers of

the Parental Alienation Syndrome, which 'begins from the premise that children

who allege serious abuse by a parent are lying and that they are made to lie by

an apparently protective parent'. However, 'extensive empirical research

findings [have shown] that false allegations of child abuse are very much the

exception rather than the rule'.[82]

2.9

A Family Law Council inquiry has found that neither the

State or Territory child protection system nor the Family Court system

necessarily protects children and that this systemic failure could have the

most serious and damaging consequences for children's lives.[83] The Family Law Council has recommended

measures including the establishment of a Commonwealth independent Child

Protection Service (CPS) to investigate family law child abuse concerns and to

avoid duplication with State and Territory child protection authorities' work.

The CPS would be based on the Magellan Project, a Melbourne-trialled program

that assists quick resolution of family law cases involving allegations of

child abuse, independently of State and Territory child protection services.[84] Under the project, which includes

agencies such as the Family Court, Legal Aid and Police, the Victorian

Department of Human Services undertook to investigate all child abuse

allegations and to provide a written report to the Court. As well, uncapped

Legal Aid was made available to children, and other parties (subject to the

normal means and merit test).[85]

2.10

Overall, the Magellan Project proved to be valuable especially

for its ability to streamline processes and decrease the proportion of distressed

children in the courts. Its other recorded attributes include: higher levels of

satisfaction, both for parents and for their children; and an emphasis on

minimising harm to the child and providing transparency processes for the child

and his/her parents.[86] Magellan

has been implemented in all Family Court registries in all States except New

South Wales[87] and in Western

Australia (where the Columbus Project provides case

management similar to that undertaken by Magellan).[88] The Commonwealth Government has not implemented

the Family Law Council's call for a national child protection service; however,

a number of inquiries into children's care and protection including the NSW

Parliament's Standing Committee on Social Issues, have expressed support for

the establishment of a national child protection service.[89]

International agreements and

treaties

2.11

The Commonwealth Government has also supported, signed

and ratified a number of international agreements regarding the rights of the

child. The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) has a

statutory responsibility for promoting the United Nations Convention on the

Rights of the Child (UN Convention) in Australia.

HREOC's work includes examining existing and proposed laws to ascertain their

consistency with children's rights, advising governments and investigating complaints

about Commonwealth practices that may be inconsistent with children's rights.[90]

Funding of programs

2.12

The Commonwealth has established and maintained initiatives

for children, young people and families mainly through the Department of Family

and Community Services (FaCS) which funds assistance and intervention programs.

Many Commonwealth programs have been devolved to the States and Territories for

services to families in crisis. Such programs are discussed later in this

chapter.

State and Territory child protection

2.13

While the Commonwealth has some role in protecting children

and young people and their families, the prime responsibility for children's

courts and child welfare legislation and associated administrative bodies,

particularly for abused and neglected children rests with State and Territory Governments.

State and Territory Governments have branches within their community services

departments to deal with issues related to children's care and protection.

Examples of State and Territory departments which deal specifically with the

care and protection of children are the NSW Department of Community Services

(DoCS), the Queensland Department of Child Safety, Western

Australia's Department for Community Development, the

South Australian Department of Families and Communities and the Department of

Health and Community Services in the Northern Territory.

In the ACT since the Vardon Inquiry into the safety of children in care, an

Office for Children, Youth and Family Support has been set up in the Department

of Disability, Housing and Community Services.

2.14

When warranted, State or Territory child protection

authorities may take action under their legislation in their children's or

youth courts for determination if a child or children are in need of care and

protection. Any subsequent child protection order may result in a child being

removed from a family and placed in some type of out-of-home care such as

foster or kinship care. The following legislation is in place in States and

Territories; some of which is under review or being updated:

|

New

South Wales

|

Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Act

1998

|

|

Victoria

|

Children and Young Persons Act 1989

|

|

Queensland

|

Child Protection Act 1999

|

|

Western

Australia

|

Children and Community Services Act 2004

|

|

South

Australia

|

Children's Protection Act 1993

|

|

Tasmania

|

Children, Young Persons and Their Families Act 1997

|

|

Australian

Capital Territory

|

Children and Young People Act 1999

|

|

Northern Territory

|

Community Welfare Act 1983

|

2.15

The legislation provides the legal framework for

matters concerning children such as foster care arrangements, residential and

professional care, processes to notify authorities about child abuse, and where

appropriate, details of the appointment, roles and responsibilities of

officials such as children's commissioners and children's guardians. They also

outline the roles of administering departments and grounds under which children

and young people may be placed by community services departments on care and

protection orders, and the rights of parties in any legal proceedings for the

protection of children and young people.

2.16

Some evidence has described the underlying tenets of Australia's

welfare laws as out of date:

...the social mores and government priorities that have influenced

the development of child welfare services in Australia

during the last century...were inculcated into earlier child welfare legislation

and practices. This...has [affected] the current child welfare laws, their

administration, and the collective or corporate conscience of government

officers...implementing child welfare and protection laws.[91]

2.17

As noted, there are differing legislative provisions

among the States and Territories that govern children's care and protection. All

Australian jurisdictions, except Western Australia

have mandatory reporting of child abuse requirements;[92] however, even among those with

mandatory reporting, variations exist about whom has been mandated and what

incidents or circumstances require a mandated person to report.[93] Regardless of the jurisdiction, Family

Court personnel, counsellors, mediators or child welfare officers, who in the

course of their work during family law proceedings, form a suspicion on

reasonable grounds that a child has been abused, or is at risk of being abused,

are subject to mandatory reporting rules.[94]

2.18

State and Territory legislative provisions differ about

when a child would be classified as being in need of care and protection or as

being at risk. Some jurisdictions' Acts are more explicit and detailed than

others. Definitions vary for the reporting, investigation and intervention in

cases of suspected abuse.[95] Differences

exist among jurisdictions classifications of abuse, ie, physical, sexual,

emotional or neglect. The definition of what constitutes child abuse and

neglect has changed and broadened over the last decade. The focus of child

protection in many jurisdictions has shifted away from the identification and

investigation of narrowly defined incidents of child abuse and neglect towards

a broader assessment of whether a child or young person has suffered harm.[96] Each jurisdiction has a point below

which statutory child protection intervention is not warranted. These

thresholds vary, with Victoria,

NSW and South Australia respectively

determining 'significant harm', 'in need of care' and 'at risk'. The

differences are critical since more children might be assessed to be in 'need

of care' than experiencing 'significant harm' and the threshold test is clearly

the first decision that faces child protection workers in determining if they

have a mandate to intervene. The variations across Australia

lead to a lack of consistency as to whether a child's maltreatment allegation

will be investigated.[97]

2.19

The Tasmanian Commissioner for Children advised that the

office had been seeking clarification about definitions, procedures and

processes for investigating allegations and claims of abuse as there was a view

that definitional elements may contribute to allegations being unsubstantiated.

The Commissioner noted that in Tasmania,

the standards of proof required for what would constitute child abuse vary

among agencies including between the Tasmanian child protection system and the

Tasmanian Police. The Commissioner stated that this can make situations

difficult particularly where children's evidence is up against that of adults.

The Commissioner also considered that even where the Police find an allegation

of abuse of a child to be unsubstantiated, the Commissioner's office may nevertheless

need to have a continuing role in assisting the child.[98]

2.20

There are many other differences among jurisdictions'

legislation including in relation to the age at which a person is classified as

a child or young person and the types of court orders available.[99] Across jurisdictions court orders for children

which include arrangements for accommodation, custodial and responsibility

issues, contact and residency, ministerial timeframes for supervision of the

child, restraining orders against certain persons, and short-term or long-term

guardianship, all vary.[100] A tenet

which shares common ground in legislation across jurisdictions is that which

links a child's need for care and protection to situations where no appropriate

parent(s), guardians or relatives are available to care for the child.[101]

2.21

Various

inquiries into Australia's care and protection system have advised of

the need to bring definitions into line across jurisdictions. South Australia's

Layton Review considered legislative definitions of terms such as 'child abuse

and neglect' for decisions where a child should be classified as 'at risk' and

if such terms are explicit enough for agency staff to assess if certain

situations warrant some form of intervention. The Layton Review considered that

the combination of the definition of 'abuse and neglect' in section 6(1) and

'risk' in section 6(2) of the Children's

Protection Act 1993 (SA) were excessively complex and confusing and

recommended that they be amended and replaced. The Review considered that a definitional

concept based on the notion of risk of 'significant harm' using sections 9, 10

and 14 of the Children's Protection Act

1999 (Qld) could serve as a suitable guiding precedent.[102]

2.22

Evidence was received relating to how the 'best

interests of the child' tenet was espoused in jurisdictions' legislation

including that relating to parental rights. It was suggested that at times in

some jurisdictions too much emphasis is placed on ensuring that children remain

with their biological families. The Victorian Government noted that in

circumstances where children are notified to the child protection services

under s.119 of the Victorian Children and

Young Persons Act 1989, decisions must be based on principles that include

family preservation and the maintenance of family relationships to the extent

that this is consistent with the child's safety and wellbeing, and families and

children must be permitted to participate in the decision-making processes.[103] However a number of groups including

Centacare Catholic Family Services have described the Victorian Act as leaning more

towards parents' than children's interests:

...the way in which it seems to be interpreted through the legal

system and all of the parties to that, as well as child protection, is that the

natural family, the mother and father, are the first consideration no matter

what. That has been the experience that we have noticed – and certainly the

experience that I noticed in my previous work as well. It has swung so far in

favour of parents to the exclusion of children's needs.[104]

2.23

Berry Street Victoria agreed 'to a point' that the

pendulum has swung too far in favour of ensuring that children remain with

their natural families, but also stressed the importance of early intervention programs

to assist parents with difficulties associated with parenting.[105] The Tasmanian Commissioner for

Children acknowledged that under the Tasmanian Children, Young Persons and

Their Families Act 1997, the best interest of the child principle can be a vexed

issue:

This must of necessity focus on the rights of the child and not

an emphasis on parents, carers or service system issues. However, the

legislation clearly states that intervention to assist and support parents and

those in their position, must be the first option, and this is a right and

expectation that parents and carers can legitimately have. This is not the same

as a parent having a right to have a child live with them in a neglectful or

abusive parenting environment that compromises the care, protection, safety and

stability of the child.[106]

The NSW Commission for Children and Young people emphasised

that the wellbeing of the individual child is fundamental to a responsive and

effective out-of-home care and child protection system, rather than one focused

on adults, bureaucratic or judicial processes.[107]

2.24

The Committee was apprised of on-the-ground instances

of legislation not being adhered to. The effectiveness of aspects of Australia's

child protection laws have been questioned in other inquiries. Evidence to the

Vardon Inquiry from an ACT Law Society legal practitioner in children's and

mental health cited some workers' approaches to the legislation:

At times when I speak to child protection workers they respond

in a way that leads me to think that they see the legal and regulatory

framework in the Act as separate to and different from the child protection

framework in which they operate.[108]

2.25

The Vardon Report accepted that child protection

workers and legal practitioners approach issues differently but noted that at

times the former treated the regulatory framework as though it has been

developed in an irrelevant vacuum, without reference to child protection

principles.[109]

2.26

Looking after indigenous children's best interests was

commented upon with the Law Society of New South Wales considering that their

best interests are often not taken into account by the NSW Department of

Community Services (DoCS) and/or the courts which do not always comply with

legislation in placing indigenous children in culturally-appropriate out-of-home

care.[110] Further, the Committee

received evidence about differences in the State-Territory legal frameworks

which could result in on-the-ground inefficiencies, including for supervision

or parental responsibility orders where difficulties can be encountered over

inter-State relocations. As the welfare organisation, Mofflyn, noted:

...given the constraints on resources, there is no guarantee that

an officer in one State will administer the responsibility of that order on

behalf of another State.[111]

2.27

The lack of cross-jurisdictional agreement between NSW

and the Australian Capital Territory

for State wards moving between the two areas can present problems:

Whenever there is such separateness, there may be the potential

for children and families to be lost in the system and therefore at risk. If

such legislation is to remain the responsibility of States, it would be

necessary to obtain agreements and protocols to effectively manage movement of

children and families.[112]

2.28

Evidence highlighted a need to overhaul the social and

legal framework governing Australia's

child protection system. The Tasmanian Commissioner for Children reminded the

Committee that the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child has

expressed concern about Australia's

lack of a comprehensive policy for children federally and monitoring mechanisms

federally and locally and the disparities between jurisdictional legislation

and practices.[113] Anglicare Australia

called for high priority to be given to establishing and adopting a national

definition of child abuse and neglect, including what constitutes abuse and

neglect in out-of-home care.[114] As

well, the use of language is crucial if one is to convey the intended meaning.

The Committee recognises that the word 'abuse' can be a euphemism to describe

actions which are abusive but not necessarily illegal yet can also describe

offences such as rape or sexual assault of children which are, and always have

been, criminal offences.[115]

2.29

A further problem arising from the lack of an agreed

definition of child abuse relates to the lack of comprehensive data. While

organisations such as the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and the

Australian Institute of Family Studies collect data, figures are generated at

State and Territory levels based on the different definitions for factors such

as abuse, hence inconsistencies occur.[116]

2.30

The lack of uniformity regarding child protection

matters and the difficulties in collecting and assessing data were explained to

the Committee:

Each state has its own way of handling reports. Each state has

different ages of consent, different everything. So it just makes even

statistically collecting the data impossible.[117]

We in Australia,

still do not have a uniform set of data collected around children in care or

child protection. Some of the figures that have been quoted even this morning

on substantiation rates are very difficult to compare across jurisdictions

because of the way the legislation in different states is categorised, and the

way the departments interpret that legislation means that trying to compare it

is very fraught.[118]

2.31

Mofflyn argued that the sharing of expertise among

various government and non-government agencies and researchers is essential if

children and families in Western Australia

are to experience an equitable level of service and, as such, policies and

systems are needed to ensure this happens.[119]

Conclusion

2.32

While the Commonwealth has a role in child protection

through the Family Law Act and the UN Convention, the prime responsibility for

child protection rests with the States and Territories. Governments have

enacted legislation to establish child protection systems to identify and aid

those children who are suffering from or at greatest risk of abuse and neglect.

However, evidence pointed to many instances where there are significant

variations in the legislation. For example, there are differences in when a

child would be classified as being in need of care and protection or as being

at risk. There are differences in what would be classified as abuse and the age

at which a person is classified as a child. There are also some instances when

agencies within jurisdictions differ in their approaches to procedures and

processes for investigating allegations and claims of abuse.

2.33

The Committee considers that an assessment of the

effectiveness of standards, laws and programs to protect children and young

people would be worthwhile. It could assist policymakers to devise and

implement laws and programs that more effectively protect children than is

presently the case and reduce the need to place children in out-of-home care.

In addition, there would be a great benefit in gaining consistency with the

various definitions across all jurisdictions.

2.34

The Committee's recommendations concerning the need for

a national approach to child protection legislation and programs are contained

in Chapter 7.

Child protection processes

2.35

Reports of abuse of children across Australia

are all too common, including in out-of-home care. Below is a brief outline of

care and protection agencies' processes to protect children.

Notifications, investigations,

substantiations, mandatory reporting

2.36

Investigations of abuse allegations can be complex and

protracted and involve many parties including the child, families, foster

carers, child protection bodies and the courts. Children assessed to be in need

of protection can come into contact with community services departments through

a number of ways including via reports of concerns about a child from someone

in the community, a professional mandated to report suspected abuse and

neglect, the child or a relative. State and Territory child welfare

departments' assessments of child protection notifications may result in an

investigation, a referral to other organisations, or, no further protective

action. On an investigation's finalisation, a notification is classified as

'substantiated' or 'not substantiated', the former being where it is concluded

that the child has been, is being or is likely to be abused, neglected or

otherwise harmed.[120]

2.37

Of significance is that child protection policies and

practices are continually changing and evolving. Trends in child protection

numbers should be interpreted carefully, as such changes in policies and

practices impact on assessing the numbers of children in the child protection

system in different ways.[121]

2.38

The WA Department for Community Development explained

that in investigating allegations of maltreatment of children including those

in care, priority 1 case investigations are commenced within 24 hours. Cases

which have a priority 2 classification have less immediacy and it may be two to

five days for the response and starting process. The department emphasised that

it also investigates claims of abuse from earlier times:

If the child is still a child, yes, we would go through that

process. But if it is an adult, it is really the responsibility of the police.

If they are an adult making an allegation of abuse that happened to them in

care when they were a child, they should really go to the police and then we

would provide the information to the police.[122]

2.39

As mentioned earlier, there are definitional

inconsistencies in Australia's

laws about what might constitute abuse or neglect. Some jurisdictions

substantiate situations where child abuse and neglect have occurred or are

likely to occur; others substantiate situations where the child has been harmed

or is at risk of harm and the parents have failed to act to protect the child.[123] The Tasmanian Children's

Commissioner considered that there is a possibility that investigations' procedures

about abuse may be contributing to them being concluded as unsubstantiated. The

Commissioner made the point that a non-substantiated outcome does not

necessarily indicate whether abuse has occurred or not. The Commissioner noted

that the mere fact that an allegation has been made can show that something is

amiss in a child's life and therefore assistance of some kind may be required:

Non substantiation does not necessarily indicate that abuse did

not occur, just that there is insufficient evidence. This is an entirely different

matter to concluding that there has been no abuse.

We have to be conscious of the fact that these concerns are

serious, as in most instances, these are children who would have already

suffered abuse and neglect, prior to entry into care. Any abuse may well

adversely impact on the child even if such alleged abuse cannot be

substantiated. In cases where it is a child who makes a disclosure, I suggest

that it is best practice to always assist the child, and not only provide

assistance when there is substantiation.

Fabrication indicates a dysfunction in the past or in the

present, and non substantiation must not result in no assistance to the child.

There are three possibilities here: something may have occurred, and we cannot

prove this; something has occurred but the child has no credibility; nothing

occurred, but the child has a problem that needs attention. All three require a

protective response to identify what is of concern.

At the very least there must be reassurance to the child and

protective mechanisms put in place so that if abuse did occur, it does not

occur again.

If abuse did not occur, mechanisms must be put in place to

assess and address the child's issues, and resolve any placement or other

issues that may arise.

In all these instances, where parents, relatives and carers have

made these allegations, they too must be given such advice and assistance.

In accordance with best practice, all disclosures or allegations

of abuse must at the very least be recorded and the child assisted. In Tasmania,

my information is that all such allegations are documented, and as such can be

referred to later in any later or further concerns about the same child or the

same carer or institution.[124]

2.40

The Australian Council of Children and Youth Organisations

emphasised the importance of ensuring that in legislative interpretations, not

only should events that occur in the legal stream which often lead to a

notification of child abuse to a State child protection service be considered,

but also account should be taken of the broader perspectives which are strongly

linked to moral duty of care issues.[125]

Number of notifications and

substantiations of child abuse

2.41

The number of child protection notifications in Australia,

1 July 2003-June 2004 was more

than 219 000, ranging from 115 541 in NSW to 1 957 in the Northern

Territory.[126]

The proportion of notifications that were investigated ranged from 96 per cent

in Western Australia to 18 per

cent in Tasmania. This range

reflects differences in jurisdictional definitions and ways of dealing with

notifications and investigations. For instance, in Tasmania,

every call received is recorded as a notification and can be very broad and may

include family issues that are responded to without the need for a formal investigation

process.[127]

2.42

Although the outcomes of investigations varied across

the States and Territories, in all jurisdictions a large proportion of

investigations were not substantiated. In other words, no reasonable cause was

found to believe the child was being, or was likely to be, abused, neglected or

otherwise harmed. For example, 61 per cent of finalised investigations in South

Australia and 55 per cent in the Australian

Capital Territory were not substantiated. The

proportion of investigations that were substantiated ranged from 39 per cent in

South Australian to 74 per cent in Queensland.[128]

2.43

Across Australia,

the number of child protection notifications increased by over 21 000 in

the last year, rising from 198 355 in 2002-03 to 219 384 in 2003-04.

The number of notifications increased in all jurisdictions except Victoria.

The number of substantiations increased between 2002-03 and 2003-04 in every

jurisdiction that provided data. Increases in the numbers of notifications and

substantiations may be attributable to various factors. One may be an actual

increase in the number of children who require a child protection response.

This may be due to an increase in the incidence of child abuse and neglect in

the community or inadequate parenting that causes harm to a child. It is most

likely that it indicates a better awareness of child protection concerns in the

wider community and more willingness to report problems to the child protection

departments.[129]

2.44

CBERSS cited figures from a 2002 Western Australian

Legislative Council Inquiry showing that one in four girls and one in five boys

had experienced serious sexual abuse by the age of 18 years. Other research

quoted showed that approximately 28 per cent of females and nine per cent of

males of 1 000 Australian students had been sexually abused.[130] The WA Department for Community

Development noted that the number of children and young people in care in that

State has increased by 43 per cent over the past five years and the number of

notifications of child abuse has increased by 24 per cent over the same period.

Indigenous children and young people represent the greater proportion of this

increase.[131]

2.45

However, Western Australia's

Department for Community Development (DCD) stated that most concerns expressed

to that department about the wellbeing of children do not warrant a statutory

response. It quoted the following figures:

For 2 138 finalised child maltreatment allegation

investigations conducted by the Department for Community Development in

2001-2002, harm to the child was substantiated in 49.6 per cent of cases.

A child is apprehended as in need of protection and care in

approximately 16 per cent of investigated cases. These are the children who

cannot be made safe within their families.[132]

2.46

The DCD attributed its low rates of substantiated child

abuse to a number of elements including some of the Department's preventative

strategies:

We have been doing parenting strategies for 10 years, since the

previous government. In addition to that...it is about a lot of work that is done

both at field level and through non-government services around providing

support to families. I am sure there is a need to do more of it, but we try to

work with families to prevent them from coming into the system.[133]

Care and protection orders

2.47

Where a child has been the subject of a substantiation,

a department may apply to the courts for a care and protection order for the

child, especially when other options have been exhausted. Fewer children are

placed on a care and protection order compared to the number who are the

subject of a substantiation. Apart from particular legislative frameworks,

various factors can influence departmental decisions to apply for such orders

including the availability of other options for the child.[134]

2.48

Examples of care and protection orders for children

are: guardianship, custody and supervisory orders. Other orders of a more

short-term nature, such as, interim and temporary orders, generally provide for

a limited period of supervision and/or placement of a child. Apart from being

different within jurisdictions, they vary from one State to another. Western

Australia does not have any orders that fit into the

supervisory order category and the granting of permanent guardianship and

custody of a child to a third party is issued only in some jurisdictions.[135]

2.49

Children can be placed on a care and protection order

for reasons other than abuse and neglect, including where family conflict may

require 'time out'.[136] At 30 June 2004, the majority of

children who were on care and protection orders were on guardianship or custody

orders. This varied across jurisdictions. Most children on such orders lived in

some type of home-based care (either foster care or living with relatives/kin).

Living arrangements varied somewhat by State and Territory.[137] This issue is discussed further in

chapter 3.

Numbers of children on care and

protection orders – Australia

2.50

The number of children admitted to care and protection

orders and arrangements across Australia

in 2003-04 ranged from 2 938 in Queensland

to 181 in the Australian Capital Territory.

These figures do not include NSW. There were more children admitted to orders

in every jurisdiction in 2003-04 than in 2002-03. Some children admitted to

orders in 2003-04 had been admitted to a care and protection order or

arrangement on a prior occasion. Among those jurisdictions where the

information was available, the proportion of children admitted to orders for

the first time ranged from 39 per cent in Tasmania

to 97 per cent in Western Australia.

Data on children admitted to orders

show that the largest proportion of children admitted to orders in 2003-04 were

aged under five years. Fewer children were discharged from care and protection

orders in 2003-04 than admitted to these orders. While the rates varied, in all

jurisdictions the rate of indigenous children on orders was higher than for other

Australian children: in Victoria the rate was 11 times higher for indigenous

children than for other children and in Western Australia it was over eight

times the rate than for other children while in Tasmania such a rate was twice

as high.[138]

Mandatory reporting

2.51

All Australian jurisdictions, except Western

Australia, have legislative requirements for the

compulsory reporting to community services departments of harm to children from

abuse or neglect. In most States and Territories, only members of a few

designated professions involved with children are obliged to report. In the Northern

Territory, anyone who has reason to believe that a

child may be abused or neglected must report this to the appropriate authority.

While Western Australia does not

have mandatory reporting, it has protocols and guidelines that require certain

occupational groups in government and funded agencies to report children who

have been or are likely to be abused or neglected.[139] The Department for Community

Development stated that in Western Australia

such mandatory reporting only relates to reporting cases that involve children

under 13 years who have a sexually transmitted infection.[140] As mentioned, various Family Law

personnel are required to report cases of suspected child abuse which comes to

light in the course of their employment.

2.52

Opinions differ about the merits or otherwise of

mandatory reporting. In 2003, the Vardon Report in the ACT considered this

issue and noted that South Australia's

Layton Review had recommended an increase in the number of mandated persons on

the basis that mandatory reporting creates a climate where the community can

confidentially report suspected child abuse and the State will intervene to

protect the child. In that context, it was argued that mandatory reporting

provides accurate information with a higher substantiation rate, sends a clear

message that child abuse will not be tolerated and resolves ethical dilemma

issues associated with confidentiality. The Vardon Report considered various

jurisdictions' stances on mandatory reporting and noted that some views are

that it uses large amounts of resources for investigation and legal processes

and does not necessarily inform the responsible government agency of all

suspected child abuse so that a child in question may not be brought to a

department's attention for an appropriate response.[141]

2.53

Evidence suggested that mandatory reporting increases

the number of reports about child abuse, many of which do not result in a

substantiation of abuse. It also creates support demands for people involved

which are often not able to be met by community services. Anglicare Victoria

cited Victorian figures showing that of 40 000 reports per year, 11 000-12 000

were investigated and 2500 were substantiated, but very limited resources were

provided to the welfare agencies for cases, substantiated or otherwise.

We know that we have these 2,500 to 3,000 children needing some

additional support. We do not have the services to provide to them...we [do not]

necessarily need to do away with mandatory reporting but...we have to devise a

more efficient and effective way of actually dealing with the reports that come

in.[142]

2.54

A Queensland

law academic, Dr Ben

Mathews, noted that for

mandatory reporting to work effectively, people who are mandated to report need

training:

The key argument against extending a broad reporting obligation

to teachers and other professional groups is obviously the increase in the

number of reports...[it] is not a principled basis for opposing that extension of

a broad obligation. It is really an argument against inaccurate reporting. That

can be addressed through proper training, resourcing and support for groups who

are meant to report and for the investigative and treatment bodies.[143]

2.55

The WA Department for Community Development expressed

similar sentiments to that of the Tasmanian Commissioner for Children that any

allegations of abuse from a child or other person about a child, often show that

the child requires assistance, irrespective of an investigation's outcome. The

Department explained the rationale for the WA Government's policy in not having

a legislative requirement for mandatory reporting:

What we want to have is a shared community concern around the

issues of children needing care and protection. We want people to know how to

bring that matter to us, but we do not want to overload the system with lots of

concerns. The history of what tends to happen when mandatory reporting is in place

is that there are many matters that get referred through because people think

they are obliged to report, rather than people making some informed judgements.

We have extended the range of our child protection procedures

with key government departments. We have also been working with our

non-government services around having a better appreciation of what is required

when children are at risk of significant harm...We certainly want issues of

significant harm referred to the department, and we will act upon those, but we

want to work with other agencies in taking a shared approach to the issue.

...What we do know is whilst...the rate of the reporting skyrockets

with mandatory reporting, the rate of substantiation actually does not really

change that much. You then have a great body of work more to do with family

concerns – low-level concerns about parenting skills et cetera – and so you

have a vast amount of work being put into quite intrusive child protection

intervention where there is no substantiation of child maltreatment.

And there are no services provided to those families

traditionally because when talking about resources getting dragged to the front

end, mandatory reporting is a classic example: it pulls the resources out of

the rest of the organisation in order to respond to the huge numbers that come

in. In New South Wales last year there were something like 170 000

reports.

...That is why we introduced a differential response rather than

mandatory reporting. It is not a child protection matter; it is a family

support matter. Our resources can be targeted towards supporting families in a

much less intrusive way...We found...where mandatory reporting is in place too much

of the resources are spent in investigation which leaves few resources for work

in all the other important areas that you have just identified.[144]

2.56

Dr Maria

Harries explained that the more one

increases the demands on people to report the more likely they will report

anything 'because people are frightened of not reporting':

So...the less likely it is that you are actually reporting the

seriously at risk and the more energy is going to the less seriously at risk.

The consequence of that is that most places that have mandatory reporting put a

cap on what they are actually going to investigate, so substantiation rates go

down initially because there is so much been reported that is not serious. As

they reduce the level at which they start investigating, the substantiation

rates start going up because they are saying, 'We're only going to investigate

if there is a physical injury, if the child is under six, et cetera'. So when I

say it is a matter of numbers, substantiation rates are all to do with the

thresholds of what is reported and who reports, and then what the agency has to

be able to investigate.[145]

2.57

Dr Harries

noted that Western Australia's

substantiation rates are seen as low because only high-risk cases are

investigated. She noted that being able to locate and assist the children most

at risk and their families is critical but mandatory reporting does not necessarily

achieve that situation:

It varies all the time...So there is a two-pronged system that we

are trying to develop in Western Australia...we have identified a group of

families and their children who are in need and another group of families who

appear to be harming their children, and those children have a different sort

of need. We have tried to manage that two-pronged system. In the other states,

they are put into one.

It is argued that WA has lower substantiation rates because it

takes into its system as a substantiation something that is significantly a

risk issue. It does not take all the other things into account as well. It is

meant to be hiving off the in need ones earlier. In fact, substantiation rates

are not a good measure of anything at all. Substantiation in one jurisdiction

is not substantiation in another. That is what Francis

Lynch was talking about earlier when he

talked about national standards. In every state we have different standards for

substantiation.[146]

2.58

If a positive outcome of mandatory reporting were that

it raised alarm bells for the departments and authorities about a child's need

for help, then mandatory reporting would be more worthwhile. According to Dr

Harries, the evidence is that mandatory

reporting often does not necessarily reveal any problems which is significant

given that irrespective of its findings, often no assistance is provided to the

family anyway. Like the Tasmanian Commissioner for Children (mentioned

earlier), she opined that just the allegation of abuse itself is an indication

that the child and/or her family needs help. The reality is however, that often

help is not provided:

...if it is a mandatory report, you are compelled to do a forensic

investigation. You blast in, like police, and you verbally, psychologically,

physically – however you do it – assault a family. You are investigating

whether a crime or something terrible has happened. The impact on families is

catastrophic. In the bulk of those investigations the report is not

substantiated, so what have you done to that family? Secondly, even if you find

that the family is in need...what do you say, 'No substantiation, case closed'.

So you not only assault the family but you do not even offer support...what we

are seeing with mandatory reporting worldwide, not just in Australia, is that

in the forensic investigation of abuse we are further damaging families, we are

not supporting families and children at all and, worse still, the bulk of

children who die are known to agencies.[147]

2.59

The resources are often so stretched that such help is

not available. Dr Sachmann

stated:

There is a growing amount of evidence to demonstrate that, where

mandatory reporting is in existence, so much of the organisation structure is

geared towards investigation, full stop.[148]

2.60

Similar sentiments about mandatory report were

expressed by the Queensland Crime and Misconduct Commission's inquiry into the Queensland

foster care system:

Importantly, whatever the merits of the different views about

mandatory reporting, there is little point to the extension of mandatory

reporting in a system that cannot respond to the demands placed on it by such

reporting.[149]

Government funding – care and

protection of children

2.61

Recurrent expenditure on child protection and

out-of-home care services was at least $1041.14 million across Australia

in 2003-04, representing a real increase of $110.8 million (11.9 per cent) from

2002-03. Nationally, out-of-home care services accounted for the majority

($638.6 million – 61.3 per cent) of this expenditure. Some jurisdictions have

difficulty in separating expenditure on child protection from that on

out-of-home care services. Nationally, real recurrent expenditure per child

aged 0-17 years was $217 in 2003-04. This varied across jurisdictions, from

$296 in the ACT to $131 in South Australia.

Real recurrent expenditure on child protection and out-of-home care services

per child aged 0-17 years increased in all jurisdictions between 2002-03 and

2003-04.[150]

2.62

Funding increases for programs to identify families at

risk and prevent or at least stem abuse or neglect of children and young people

has occurred across all jurisdictions. For example, in NSW, increases in

allocations for child protection services include those for intervention and

prevention approaches and accommodation for children requiring costly services,

while Queensland's extra

government funding has provided a range of initiatives including additional

staff for the new Department of Child Safety.[151]

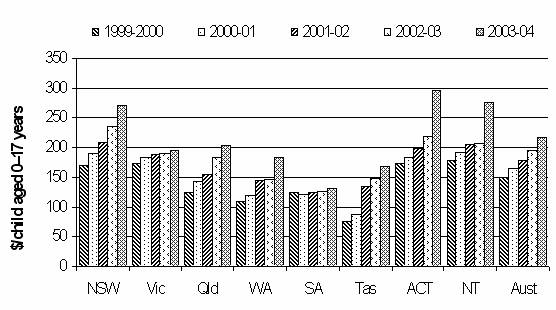

Figure 2.1: Real recurrent expenditure on child protection and out-of-home

care services (2003-04 dollars)

Source: Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services 2005, Volume 2, January 2005, p.15.11.

2.63

However, some welfare providers argued that governments

were shirking their funding responsibilities and that out-of-home care

providers were increasingly being pressed for funds to meet children's basic

needs such as educational costs, uniforms and recreation:

The states and the Commonwealth, I believe, have neglected their

responsibility to adequately resource a child welfare system in this state [Victoria]

which would enable community service organisations and others to deliver the

best quality practice that now the community, at least verbally, seems to be

demanding.[152]

...we subsidise it from our other areas...We are subsidising the

present contract significantly over...We do not mind doing that...but if you repeat

that across all the non-government organisations in Australia, the shortfall is

becoming huge...In this financial year we will probably subsidise the service

to the extent of around $100,000. Next year it will possibly be closer to

$200,000.[153]

2.64

Youth Off The Streets stated that it does not receive core

government funding, even though it often provides community support programs

for the NSW Department of Community Services when departments are unable to

manage the young person's behaviour:

...despite an estimated number of more than 45,000 young people

having used our services since our establishment in 1991, we have yet to

receive core funding from the government.[154]

2.65

Youth Off The Streets emphasised that it requires the

certainty that core funding would provide. The organisation noted that

short-term funding contracts under which DoCS presently allocates funding to

groups such as Youth Off The Streets, are inadequate to meet children's

requirements, which in reality are more often long term than ad hoc. That organisation regularly

provides children and young people with ongoing residential, educational

rehabilitation, therapeutic and community support outreach services. Youth Off The

Streets quoted a 2003 NSW Ombudsman's out-of-home care funding report which

recommended that DoCS identify the extent of need and appropriate models and

costs for residential care services so that a policy and funding framework could

be developed to guide the planning and provision of residential care.[155]

2.66

The issue of funding for youth homelessness and

juvenile crime prevention programs was also raised in evidence:

In our own state [Queensland]...for

every $1 we put into crime prevention work, we put $58 into prisons and courts

and all the rest of it. I think the same is true in the Commonwealth area with

regard to the dollars that we put into counselling versus the dollars that we

put into the Family Court. We are a reactive society, not a proactive society.[156]

2.67

Some agencies noted that governments' accountability

rules and procedures for funding to welfare groups, often add to pressures for

the non-government sector in delivering effective programs and support to

families:

Since the 1990s, it has increasingly been the case that funding

parameters and shrinking resources, rather than best practice, have been the

major drivers of change in the child-care sector. The pressure on the

non-government sector to provide increased accountability in administrative compliance

has made it extremely challenging for agencies to remain focused on outcomes

for children and families.[157]

Getting support from government funding departments under the

current tendering processes is costly and requires resources that would be better

spent in the program area. Some government departments...refer young people to us

but do not provide us with funding for these placements. We do not receive the

maximum funding levels available for our schools commensurate with their status

as 'special schools' from the Department of Education and Training because we

need to provide detailed psychological reports on each child, which we cannot

provide because of the lack of administrative resources and because

pathologising children is inimical to our organisational philosophy.[158]

2.68

Issues regarding a constant lack of resources for

programs and the continual strains on the public purse were regularly raised.

Mofflyn considered it vital to maximise efficiencies to achieve the greatest

impact with the least possible financial outlay and ranked funding equity and

quality of care issues highly. Funding needed to:

Be provided to pilot new initiatives or investigate, through

evidence-based research, what modern children and families need by way of

support and intervention...Be broad enough to enable agencies to provide services

according to the child or family's individual need in order to be most

successful...Recognise that training, support, supervision and the professional

development of staff and volunteers are the key to providing quality care and

important to core program outcomes[159]

Conclusion

2.69

The causes of child abuse can often be traced back to

problems and disadvantages in families' lives including drug and substance

abuse, lack of finances, marriage breakdown and unemployment. Economic and

social stress can also lead parents to become less nurturing and rejecting of

their children and that children living in poverty have a high incidence of

abuse and neglect. Evidence points to an increase in the number of notifications

and substantiations of abuse and neglect.

2.70

All States and Territories except Western

Australia have legislative requirements for mandatory

reporting. Evidence for and against mandatory reporting was received. Arguments

have been put that the resources for reporting could be more effectively

directed elsewhere and that mandatory reporting generates unnecessary reporting

and strains the system to the point where often assistance is not able to be

provided for people who are in genuine need. Others have noted that any report

of child abuse, irrespective of whether it is proved or not, is evidence that

something is amiss in the life of that child and his or her family. If

anything, this shows too that effective support programs and early intervention

measures must be available for families and young people and they must be

properly promoted and advertised so that people know of their existence.

2.71

The Committee considers that the effectiveness of

mandatory reporting as it currently operates in various jurisdictions needs to

be assessed to ensure that resources are being effectively allocated to improve

the protection of at risk children.

Recommendation 2

2.72 That State and Territory Governments consider reviewing

the effectiveness of mandatory reporting in protecting and preventing child

abuse, and in conducting such a review, they particularly focus on the

successes of the various options used in care and protection systems, in

comparison with mandatory reporting.

Children's commissioners, children's advocates, children's guardians, etc

2.73

In addition to the services provided through State and

Territory welfare departments, various offices exist to promote and protect

children and their rights. These include children's commissioners, children's

advocates and children's guardians.

State and Territory children's

commissioners

2.74

Currently, offices of commissioners for children and

young people exist in NSW, Queensland

and Tasmania. Discussions have

occurred for the introduction of such an office in Victoria,

South Australia and the ACT and a

commission is to be established in Western Australia

in 2005. While children’s commissioners' powers vary across Australia,

they operate under the principle of promoting and protecting children and their

rights as defined in the UN Convention. The functions of the Australian models

relate to systemic investigation and inquiry rather than individual advocacy

for children. Witnesses suggested the establishment of a children's

commissioner in each State to provide a legal service for children and those

persons who were abused in care as children to reduce their disadvantages in

seeking legal recourse.[160] As well,

many individuals and groups suggested the establishment of a national

children's commissioner. This issue is discussed later in the chapter.

New South

Wales

2.75

Established under the NSW Commission for Children and Young People Act 1998, the NSW

Commission's role relates to ensuring the safety, welfare and wellbeing of

children, and a cooperative relationship between children, their families and

the community.[161] The office's

primary functions include promoting the participation of children in decision

making, monitoring the wellbeing of children in the community, making

recommendations to government and non-government organisations about

legislation, policies and practices that affect children and young people, and

monitoring people who are involved in child-related employment.[162]

Queensland

2.76

The office of the Queensland Commissioner for Children

and Young People and Child Guardian was established under the Queensland

Commission for Children and Young People

and Guardian Act 2000. The Commissioner's responsibilities include

investigating and reviewing complaints from children or young people about

government-funded services. The Commission's priorities relate to children and

young people in some form of out-of-home care or detention centre and children

who have no one to act on their behalf. The Commission assists indigenous

children and young people and those who do not speak English, have a disability

or are geographically isolated. The Commission's powers include advocacy, and

monitoring and reviewing laws, policies and practices.[163] The Queensland Commissioner has a

statutory authority to investigate complaints that relate to services provided

or required to be provided to a child who is subject to orders or actions under

various State Acts such as the Child

Protection Act 1999 (Qld) or Juvenile

Justice Act 1992 (Qld). The Child Guardian's tasks include monitoring,

auditing and reviewing agencies which provide services for children and young

people in the care system.[164]

Tasmania

2.77

The Commissioner for Children in Tasmania

has a function under s.79(1)(d) of the Children,

Young Persons and Their Families Act 1997, 'to increase public awareness of

matters relating to the health, welfare, care, protection and development of

children'. Under s.79(1)(f), the Commissioner can 'advise the Minister on any

matters relating to the health, welfare, education, care, protection and

development of children placed in the custody or under the guardianship, of the

Secretary under this or any other Act'. As the Commissioner has noted:

This section gives me a function with respect to children in any

welfare care, but in addition, it also gives me a role with respect to children

and young people who are in juvenile justice custody.[165]

2.78

The Commissioner's tasks are linked with s.124(1) of

the Youth Justice Act 1997, for

children and young people in custody, where the Secretary of the Department of

Health and Human Services is responsible for their 'safe custody and well

being'. Other roles of the office include notifying the Department's division

of Children and Families of any abuse allegations for investigation and

internal review. In such cases, the Commissioner's brief includes scrutinising

systems issues related to policy, practice and service delivery, to ensure that

they are carried out in accordance with the best interest of the child for

matters such as health, care and welfare. The Tasmanian Ombudsman can also

investigate such claims if they involve an administrative decision with which a

child, parent or carer is dissatisfied.[166]

Victoria

2.79

The Victorian Institute of Law has proposed the

establishment of a Victorian Commissioner for Children and Young People with

functions that include ensuring children's participation in decisions about

themselves and their lives and that children's rights and interests are taken

into account by parliamentarians, government and local authorities, public

bodies and voluntary and private organisations in relation to services provider

responses to complaints about services for children. The office's other roles

include promoting and monitoring advocacy and other support services and

ensuring wide consultation including a capacity for the Commissioner to review

and inquire into laws, practices and policies that impact on children.[167]

South

Australia

2.80

In South Australia,

the establishment of an independent Commissioner for Children and Young people

was a key recommendation of the government report into child protection, the

Layton Review. As in Queensland, the South Australian model proposed that the

Commissioner have the ability to: be an advocate for children and young people;

conduct inquiries; promote awareness of the rights of children and young

people; influence law, policy and practices; intervene in legal cases involving

the rights of children and young people at the systemic level; initiate test

cases or support legal actions on behalf of children and young people; and

conduct research.[168]

Australian

Capital Territory

2.81

Support for the establishment of an ACT Commissioner

for Children and Young People can be traced back to an ACT Legislative Assembly

committee report, The rights, interests

and well-being of children and young people. In response to the more recent

inquiry, the Vardon Report, the ACT Government is committed to establishing

such an office where some of the Commissioner's tasks would include advocacy,

standard-setting for government-funded services and powers to convene a

tribunal to review decisions of government-funded services dealing with

children and young people. A significant task would be the introduction of a

review role relating to people who plan to work in jobs associated with

children or young people. The ACT Government is considering possible structures

for a children's commissioner including roles that include integration with the

Office of the Community Advocate.[169]

Western

Australia

2.82

In December 2004, the Western Australian Minister for

Community Development announced the finalisation of a model for the State's new

independent children's commission, to start work in 2005. The WA model includes

'special attention to indigenous children'. The proposed commission's role

includes advocating for children and young people generally, promoting children's

participation and the community's understanding of issues affecting children,

monitoring and advising the government on legislation, policies and practices

and conducting inquiries and research. The model has been developed after

consultations with commission counterparts in NSW and Queensland

as well as groups and individuals such as the CREATE Foundation, Professor

Fiona Stanley,

Magistrate Sue Gordon, Meerilinga and 231 children and young people across the

State.[170]

Children's guardians and other

offices

Children's guardian - New South

Wales

2.83

The NSW Office of the Children's Guardian was

established under the NSW Children and

Young People (Care and Protection) Act 1998

to promote the best interests and rights of children and young people in

out-of-home care in NSW. The need for an independent representative has been

highlighted in instances of conflict of interest, such as where a Minister has

the dual roles of responsibility for a facility where a child resides and is

also the child's legal guardian.[171] Also

included in the rationale for the appointment was the recognition of the lack

of power of children in out-of-home care, especially those facing systems

failure problems. The Guardian's functions include assuming the parental

responsibilities of the Minister for a child or young person in out-of-home

care, accrediting foster care agencies, removing children from inappropriate

placements, participating in conferences about children's court processes and

assisting with dispute resolution and departmental funding decisions.[172]

Guardian for children and young

people – South Australia

2.84

Although a commissioner for children has not yet been

established in South Australia,

that State recently appointed a Guardian for Children and Young People. The

guardian has the role of advocate for all children and young people by advising

the Minister for Families and Communities on whether the needs and interests of

children are being met. The guardian will ensure that child protection and alternative

care systems, and other government services such as health and education, are

child focused and work to improve the wellbeing of all children. Unlike the

Queensland Commission, the guardian will not receive and investigate

complaints, conduct research, and there is no screening function for

child-related employment.[173]

Advocate for Children in Care - Victoria

2.85

Established in April 2004, the office of the Victorian Advocate

for Children in Care has a comprehensive role entailing advocacy and representation

of children in out-of-home care. The role includes a focus on encouraging

children's participation in decision-making processes and ensuring quality

services, standards and compliance and monitoring of the sector. Among the

Advocate's 'core functions' are those related to developing a Charter of Rights

for Children in Care; undertaking independent and systemic quality reviews of

case management and care planning for out-of-home care at the request of or

with the approval of the departmental secretary; and, in conjunction with local

Aboriginal communities, monitoring adherence to the Aboriginal Child Placement

Principle for the placement of indigenous children in out-of-home care. The

Advocate's office has identified major work priorities such as those to address

children and young people as primary constituents and ensuring systemic quality

improvement and the development of communication and relationships with stakeholders.[174]

Office of the Public Advocate – Queensland

2.86

Created under the Queensland

Guardianship and Administration Act 2000,

the Queensland Public Advocate provides systemic advocacy for adults with a

decision-making disability. This group includes people with a psychiatric

disability, an intellectual disability, an acquired brain injury or some form

of dementia. Included in the Public Advocate's legislative functions are those

to promote and protect the rights of such adults from neglect, exploitation or

abuse. The role of the Public Advocate is to identify widespread situations of

abuse, exploitation or neglect of people with impaired capacity due to

shortcomings in the systems or facilities of a service provider. The Public

Advocate reports these findings to State Parliament.[175]

Office of the Adult Guardian – Queensland

2.87

The Adult Guardian is an independent statutory officer

operating under the Queensland Guardianship and Administration Act 2000.

The Adult Guardian protects the rights and interests of adults with impaired

capacity and supports and advises their guardians, attorneys, administrators

and other people who provide informal assistance on matters including those

related to health and finances. The Adult Guardian can investigate reports of

complaints about exploitation, abuse or neglect of a person with impaired

capacity or complaints against the actions of a person who has been given

enduring power of attorney. If a person is found to have behaved irresponsibly,

the Adult Guardian can suspend a power of the attorney, conduct an audit and

obtain a warrant to remove an adult who is being abused, exploited or

neglected.[176]

Office of the Community Advocate – Australian

Capital Territory

2.88

The Office of the Community Advocate (OCA) has a

monitoring role towards children and young people in need of care and

protection, under the ACT Children and

Young People Act 1999. Under the Community Advocate Act 1999 the

Community Advocate provides systemic advocacy for children and young people in

the ACT.[177] The OCA's powers and

functions are wide and include those designated in various Acts including the Mental Health (Treatment and Care) Act 1993

and the Guardianship and Management of

Property Act 1991 and those relating to services, facilities and supports

for people with a disability. The OCA may engage in individual or systemic

advocacy on behalf of children and young people but it is not a formal

complaints agency.[178]

Commonwealth, State and Territory

Ombudsman Offices

2.89

The Commonwealth and State and Territory Governments