Chapter 4 - Unemployment and the changing labour market

...the lack of employment is the biggest single cause of

poverty in Australia at the moment. It is a key area that needs

to be looked at in any poverty inquiry.[1]

4.1

Unemployment, particularly long-term unemployment, is the most

significant cause of poverty and disadvantage in the Australian community.[2]

In the immediate post-war years through to the mid-1970s, Australia, like most

advanced Western countries, maintained very low levels of unemployment. Since

the mid-1970s the achievement of full employment has progressively lost ground

as a policy priority, with the consequence that large numbers of Australians

have been denied this basic right to work. As a consequence, unemployment and

underemployment have remained at unacceptably high levels for over two decades

and this has led to major social and economic costs for the community.

4.2

Unemployment has serious economic, social and emotional impacts.

Unemployment puts severe financial and emotional stresses on families and leads

to a loss of self esteem and social status. These can lead to family conflict

and separations; to psychological and physical health problem; to homelessness

and to a range of disadvantages for children growing up in these families. The

effects of unemployment, however, reverberate beyond the jobless – unemployment

reduces economic output and national income and the wider community is

adversely affected with further demands placed on governments via the social

security system and on the charitable sector.

4.3

This chapter looks at the changing labour market over recent decades,

the definitional issues around unemployment and underemployment, and the

relationship between joblessness and poverty. The chapter then reviews various

issues related to unemployment and the changing labour market and strategies to

address problems in relation to these issues. These include:

- the creation of more jobs;

- role and effectiveness of the Job Network;

-

the problem of the long-term unemployed;

- the problem of the 'working poor';

- increased casualisation of the workforce; and

-

the impact of recent industrial relations changes on wages and

working conditions.

The changing labour market

4.4

Over recent decades there have been significant changes in the nature of

employment in Australia. Evidence to the inquiry indicated the following

trends:

-

Employment in business services, retailing, hospitality and

health and community services has grown, while that in the manufacturing and

utilities sectors has declined.

- The proportion of jobs which are part-time or casual has

increased, as has the proportion of lower-paid jobs within the service sector.

Casual employment increased by 68 per cent in the 1990s. Permanent jobs

increased by only 5.3 per cent over the same period, but the number of full-time

permanent jobs actually fell by about one per cent. By August 2002, 27.3 per

cent of all wage and salary earner jobs were casual and 66 per cent of these

were part-time.

- Unemployment rates have increased markedly since the 1970s as has

the average duration of unemployment (see below).

- Significant changes in the skills mix of occupations occurred

with increases in both low and higher skilled jobs and decreases in

intermediate skill level jobs.

- Earnings inequality increased during the 1990s. In 1991, low paid

adults employed full-time (10th percentile) earned 71.6 per cent of

those in the middle of the earnings distribution (50th percentile)

of full-time adult non-managerial employees; by 2002 the ratio had declined 4.1

percentage points to 67.5 per cent. The pattern of rising wage inequality was

particularly pronounced in the male labour market.[3]

Unemployment and underemployment

4.5

In January 2004, there were 574 100 unemployed people in Australia

(582 700 in seasonally adjusted terms), with an unemployment rate of 5.6

per cent (5.7 per cent in seasonally adjusted terms).[4]

The ABS defines an unemployed person as a person aged 15 years and over who was

working less than one hour a week in the survey week, had been actively looking

for work and was currently available for work.

4.6

As noted above, since the early 1970s unemployment rates have increased

significantly – the August unemployment rate averaged 3.7 per cent during the

1970s, 7.3 per cent during the 1980s and 8.9 per cent during the 1990s. There

has also been a very substantial increase in the average time spent unemployed.

The average duration of unemployment increased from approximately 12 weeks in

the 1970s to 41 weeks during the 1980s. Subsequently it rose to around one year

during the 1990s. As a consequence of this trend, the rate of long-term

unemployment – an indicator of the number of persons unemployed for more than

one year – more than doubled between 1980 and 1998. In January 2004, the number

of long-term unemployed equalled 1.2 per cent of the labour force, the

number of long-term unemployed persons was equal to 21.4 per cent of all those

unemployed, and more than half (52 per cent) of these people had been seeking

work for over two years.[5]

4.7 The growth in unpaid overtime also contributes to unemployment,

especially in the services sector. One submission noted that in 2001-02 unpaid

overtime had overtaken the amount of hours all people who were registered as

unemployed could have worked and as such if this overtime had been 'paid' it

would have removed all unemployment. The submission noted that 'if there is any

sign that industrial conditions have declined, then it is the amount of unpaid

overtime. The [human] cost of this unpaid overtime cannot be overestimated'.[6]

4.8

The official unemployment rate alone, however, underestimates the total

number of people wishing to work. An element of unemployment is 'hidden' – that

is, individuals who have given up looking for work and/or jobs with suitable

hours (also known as discouraged job seekers) and others with marginal

attachment to the workforce (for example, students and care-givers). When

hidden unemployment is taken into account the adjusted unemployment rate is

significantly higher. In September 2002, while there were 628 500 people

officially unemployed, there were an additional 672 100 workers who

preferred to work more hours (of these, 244 800 had actively looked for

more hours and were available to work more hours) and 808 100 who were 'marginally

attached to the labour force'.[7]

4.9 Official unemployment statistics thus significantly underestimate the

actual level of unemployment, particularly among females. Over the last decade,

hidden unemployment accounted for, on average, 16 per cent of total male

unemployment (official plus hidden unemployment). For females, the share of

hidden unemployment as a proportion of total unemployment was much higher,

equal to an average of 36 per cent.[8]

4.10 ACOSS in a

recent study noted that if hidden unemployment was included in ABS statistics,

the unemployment rate would be double the official rate. In September 2002,

ACOSS estimated there were 1 344 000 unemployed, including the hidden

unemployed, corresponding to an unemployment rate of 12.9 per cent, compared to

the official unemployment rate of 6.3 per cent. Some groups, especially

mothers, mature age people, Indigenous Australians and people with disabilities

have much higher than average rates of hidden unemployment.[9]

4.11 The Australia

Institute argued that the labour market statistics need to incorporate

information on how many hours people would prefer to work as well as how many

hours they do work. By collecting data on these items it would be possible to

measure the nature and extent of unemployment, underemployment and overwork

simultaneously.[10]

4.12 In addition to

hidden unemployment there is the issue of underemployment. Underemployment may

be defined as a situation where individuals are employed, but their skills and

productive ability are not being fully utilised. Examples include workers

employed in jobs not commensurate with their skills and persons employed

part-time but wishing to work more hours. Data for August 2003 indicate that

one third of all male part-time employed persons would like to work more hours;

the corresponding proportion for female part-time employed persons is 22.3 per

cent. The Centre of Full Employment and Equity at the University of Newcastle

(CofFEE) estimated that in August 2002, while the official unemployment rate

was 5.9 per cent, the addition of hidden and underemployment increased the rate

to 11.2 per cent.[11]

Joblessness and poverty

4.13 Evidence to the

inquiry indicated that a strong relationship exists between poverty and employment

status. Smith Family data on poverty rates of all people aged 15 years and over

by their labour force status reveal that only 4.6 per cent of Australians who

hold a full time job live in a family that is in poverty, however, the poverty

risk increases to 11.7 per cent among Australians aged 15 and over who are

working part-time. More than half of all Australians who are unemployed live in

a family that is poor.[12]

4.14 Professor Saunders

of the Social Policy Research Centre, using a different data set, stated that

the poverty rate for jobless families, that is, with no employed member, is

almost seven times higher than the poverty rate among families with one

employed person. Having two employed persons in the family causes a further

reduction in the poverty rate.

4.15 Professor Saunders

noted that there is a very large reduction in poverty associated with having

someone in full-time employment. The poverty rate is lower when there is

one full-time worker than when there are two workers in paid employment. This

highlights the fact that it is not so much access to any form of employment

that reduces the risk of poverty (although this does have a positive impact) –

but that access to full-time employment is the crucial factor.[13]

4.16 Professor Saunders

emphasised the importance of increasing the number of full-time jobs and

suggested that:

Generating high employment growth should thus be a crucial

component of any poverty alleviation strategy, but generating a growing number

of full-time jobs is even more critical. These findings as to the significance

of full-time employment for poverty reduction cast a warning given Australia's

poor record of full-time job creation in recent decades. Although joblessness

is clearly a major contributing factor to poverty among working-age families,

it does not automatically follow that any form of employment growth will

produce substantial inroads into the poverty population. Job creation is

important, but creating full-time jobs is even more so.[14]

4.17 One study noted

that employment trends over the last decade reflected a decline in full-time

employment:

- The growth of full-time employment continued to be low relative

to the growth of part-time employment. Over the decade 1990-2000, 25 per cent

of the employment growth occurred in full-time jobs while 75 per cent was in

part-time jobs.

- Within the small increase of full-time jobs there was a striking

movement away from permanent full-time employment towards casual employment.

Over the decade the number of permanent full-time jobs fell by 51 000 but

the number of full-time casual jobs increased by 333 000.

- The same movement towards casual employment among full-time employees

was evident among part-time employees. Part-time permanent employment increased

by 355 000 but part-time casual employment increased by 492 000. The

labour market has overwhelmingly moved away from permanent to casual jobs.[15]

Creating more jobs

4.18 Evidence to the

Committee indicated the importance of stimulating adequate employment growth to

address the problem of unemployment. The Brotherhood of St Laurence (BSL)

stated that:

There are not enough jobs. There is currently only one job

available in the economy for every six job seekers. No matter how good your

labour market programs, if you are not addressing the lack of jobs, then you

are never going to get huge results.[16]

4.19 In the period

from the immediate post-war years to the mid 1970s Australia, like most

advanced Western countries, maintained very low levels of unemployment. The era

was marked by the willingness of governments to maintain levels of aggregate

demand that would create enough jobs to meet the preferences of the labour

force. Unemployment rates during this period were usually below 2 per cent.

4.20 Evidence

indicated that the post-war commitment to full employment has now been replaced

by a government commitment to 'full employability' only, that is, that

unemployed people should be able to be employed, not that they are

employed.[17]

CofFEE argued that this policy is aimed at making people work-ready assisted

through a range of government programs that vary in their effectiveness – 'but

we are focusing on a diminished goal of full employability and we are

forgetting that the major aim is to create a macroeconomic environment in which

you have enough jobs and hours of work for those who want them'.[18]

4.21 Various

proposals were advanced to increase the number of jobs. These included:

- making the achievement and maintenance of full employment a

policy priority;

- developing targets for unemployment reduction, with an emphasis

on the quality of new jobs generated;

- expanding employment in the public and community sectors in the

areas of health, community services, education and environmental programs;

-

formulating an industry development policy that links education

and training, skill development, high productivity, and high quality, high wage

employment; and

- developing an incomes policy to moderate wages growth, including

high-income employees.[19]

Full employment

4.22 Many submissions

argued that full employment should be a major goal of government. Unemployment

represents a significant underutilisation of valuable human resources. In

addition, high and persistent unemployment acts as a form of social exclusion.

The costs of unemployment are significant and include not only income and

output loss, but the deleterious effects on individual self-confidence and

skill levels. Many unemployed people feel demoralised and socially isolated.

The wider community is also adversely affected and there are increased burdens

on the welfare sector and social security budgets.[20]

4.23 The Australian

National Organisation of the Unemployed (ANOU) stated that full employment

should be the centrepiece of national policy:

...[this] is founded upon our belief that every adult who wishes

to engage in paid work should have the right to do so. This right cannot be

fulfilled unless the work available meets the human need to obtain an income,

to contribute to society and to gain a status in the community through this

contribution.[21]

4.24 The BSL also

stated that 'there needs to be a commitment to full employment, which seems to

have completely dropped off the agenda over the last 15 to 20 years. That comes

a lot from an overly narrow economic focus and the desire to control inflation

at all costs.[22]

4.25 Some groups,

however, cautioned that a definition of full employment needs to be relevant to

contemporary circumstances. The Centre for Public Policy noted that:

...we would need to think about what we actually mean by full

employment. Many people working part-time chose to work part-time – they are

not working part-time in the sense that the Brotherhood suggested. They are not

necessarily looking for additional hours; they are looking for that part-time

option.[23]

Job creation schemes

4.26 Several

submissions argued for the implementation of various job creation schemes to

increase the total quantum of jobs available. The CofFEE has developed a

comprehensive public sector job creation proposal. The proposal calls for the

introduction of a Job Guarantee for all long-term unemployed people and a Youth

Guarantee, which would provide opportunities for education, technical training

and/or a place in the Job Guarantee program for all 15-19 year old unemployed

people. Details of the proposal are provided below.

Public sector job

creation – A path to full employment

The

proposal for a Community Development Job Guarantee (CD-JG) has been developed

by the Centre of Full Employment and Equity (CofFEE) and requires that two new

employment initiatives be introduced. These are a Job Guarantee for all

long-term unemployed (people who have been unemployed longer than 12 months)

and a Youth Guarantee, comprising opportunities for education, technical training,

and/or a place in the Job Guarantee program for all 15-19 year olds who are

unemployed.

These initiatives would significantly augment the

current labour market policies of the Federal Government.

Under this proposal, the Federal Government would maintain

a 'buffer stock' of jobs that would be available to the targeted groups. The

CD-JG would be funded by the Commonwealth but organised on the basis of local

partnerships between a range of government and non-government organisations.

Local governments would act as employers, and CD-JG workers would be paid the

Federal minimum award. Any unemployed teenager (15-19 year old) who was not

participating in education or training would receive a full-time or part-time

job. Equally, all longterm unemployed persons would be entitled to immediate

employment under this scheme. CD-JG positions could be taken on a part-time

basis in combination with structured training.

The aim of the CD-JG proposal is to create a new order

of public sector jobs that support community development and advance

environmental sustainability. CDJG workers could participate in many

community-based, socially beneficial activities that have intergenerational

payoffs, including urban renewal projects, community and personal care, and

environmental schemes such as reforestation, sand dune stabilisation, and river

valley and erosion control. The work is worthwhile; much of it is labour

intensive requiring little in the way of capital equipment and training; and

will be of benefit to communities experiencing chronic unemployment. It is in

this sense that the proposal represents a new paradigm in employment policy.

To implement the CD-JG Proposal at a national level

would require an estimated net investment by the Commonwealth of $3.27 billion

per annum. The net investment required to employ all unemployed 15-19 year olds

under the Youth Guarantee component of the proposal would be $1.19 billion. On

the other hand, $1.96 billion is required to employ all long-term unemployed

persons aged 20 and over. Clearly, the stronger is the private sector activity

the lower this public investment becomes.

The creation of 265 300 CD-JG jobs would be

required to eliminate youth unemployment and to provide jobs for people aged 20

years and over who are long-term unemployed. As a result, national output would

rise by $7.71 billion; private sector consumption would rise by $2.38 billion;

and an additional 68 900 jobs would be created in the private sector. The

full implementation of the CD-JG proposal would thus yield an additional

334 200 jobs. The unemployment rate would fall to 4.0 per cent, after

taking account of the labour market participation effects.

Submission

201, pp.7-11 (CofFEE).

4.27 CofFEE indicated

to the Committee that its proposal had widespread local support in Newcastle

from the business community, unions and community and welfare organisations.

The Newcastle City Council also indicated its support for the proposal to be

piloted in the local Hunter region. CofFEE stated that to implement the

proposal in the Hunter would require net investment by the Commonwealth

Government of $120.4 million per annum.[24]

4.28 Evidence

indicates that public sector job creation initiatives are an important element

in labour market policies in many OECD countries. One submission noted that an

OECD examination of the effectiveness of labour market programs concluded that

direct creation of jobs through public service employment programs may be the

only way to help many of the unskilled long-term unemployed. These job creation

programs have become more effective over time as they have become more

flexible, more targeted to local needs, and better linked to other labour

market services.[25]

An OECD study, however, concluded that direct job creation in the public sector

shows that this approach has been of little success in helping unemployed

people get permanent jobs in the open labour market. The study noted that as a

result there has been a trend away from this type of intervention in the recent

past, but it appears to be making a comeback now in some OECD countries,

especially in Europe, usually as part of a 'reciprocal obligation' on the

unemployed in return for continued receipt of benefits. However, OECD countries

continue to spend large amounts on public sector job creation programs and the

policy debate about the utility of this type of intervention continues.[26]

4.29 Other job

creation proposals were also discussed during the inquiry. Australia @

Work informed the Committee of its co-operative venture that combines low cost

housing initiatives and related job creation activities. The group pointed to

its Bulahdelah Working Village project which seeks to support a small community

of 30 families in the rural town of Bulahdelah. The project will facilitate 45

new jobs for co-op members.[27]

Conclusion

4.30 The Committee

believes that the Commonwealth Government needs to be more pro-active in

creating employment opportunities for Australians, especially in the creation

of full-time jobs. Meaningful employment for the country's citizens is

fundamental to their economic and social well-being, and also that of the

nation.

4.31 Breaking down

the barriers to employment must be a national priority. This requires a

concerted effort on two fronts – increasing the total quantum of jobs by

building on the foundations of strong economic growth, and improving the

opportunities for disadvantaged people to get their fair share of secure and

decent jobs (which is discussed later in this chapter).

Recommendation 1

4.32 That the

Commonwealth Government develop a national jobs strategy to:

- promote employment opportunities, particularly permanent

full-time and permanent part-time jobs;

- set long-term targets for increased labour force participation;

- develop better targeted employment programs and job creation

strategies;

- ensure a substantial investment is made in education, training

and skill development; and

- bring a particular focus on improving assistance to young people

making the transition from school to work, training or further education to

prevent life-long disadvantage.

Recommendation 2

4.33 That the

Commonwealth conduct a review into the dynamics of the labour force, especially

in relation to skill shortages.

Role and effectiveness of the Job Network

4.34 The Job Network

provides subsidised employment services to Australia's unemployed, especially

targeted at the more disadvantaged jobseekers. The Job Network replaced the

Commonwealth Employment Service in 1998. Most publicly subsidised employment

services were contracted out to for-profit and not-for-profit agencies under

purchaser-provider contracts determined by the Department of Employment and

Workplace Relations (DEWR). The first contract (JN1) with these providers came

into operation in May 1998, the second (JN2) in early 2000 and the latest

three-year contract on 1 July 2003 (JN3). Centrelink was established as a

Government operated gatekeeper to the system and as the single benefit payments

agency.

4.35 The Job Network

has three major functions:

- Job placement (or 'Job Matching' in the first and second

contracts) – providers match and refer eligible jobseekers to suitable

vacancies, notified by employers. Under JN3, the job placement function is not

directly part of the Job Network as general recruitment agencies and others

outside the existing Job Network will fulfil this role.

- Job Search Support – Job Network providers offer a job search

training program to jobseekers unemployed for at least 3 months.

- Intensive Support ('Intensive Assistance' in the first and second

contract) – this is the most personalised and intensive form of assistance

offered by the Job Network. The types of assistance provided includes work

experience, vocational training, job search techniques and language and

literacy training.

4.36 The major change

in the new arrangements from July 2003 is that jobseekers will be allocated to

a single Job Network provider for the life of their unemployment episode. They

will automatically go through cycles of assistance of varying intensity as

their unemployment spell increases. Where jobseekers are referred to

complementary programs, such as Work for the Dole, Job Network providers will

retain contact with them and ensure continuing job search activities.

Jobseekers unemployed for 12 months, or those at very high risk of enduring

unemployment, will receive more extensive assistance for a period of 6 months

through the customised assistance component of Intensive Support. This can

include job matching, training, job search assistance, work experience and

post-placement support. Job Network providers will get access to a funding pool

(the Job Seeker Account) to subsidise particular forms of assistance to

jobseekers – these services include fares, counselling, wage assistance and

training. Of the various functions, the intensive phase of assistance

(customised assistance) is the most important as it is targeted at the most

disadvantaged jobseekers.

4.37 JN3 implements

an Active Participation Model of employment placement and jobsearch. Under this

new system there is an emphasis on guaranteeing access to a 'continuum of

service', with the nature of that service increasing over time if the

individual is at high risk of unemployment. It aims to provide assistance that

is better targeted and timelier.

4.38 In addition to

paying commencement fees when job seekers start in the intensive phase of

assistance (which has been changed to fee-for-service payments in JN3), the

Government also rewards providers for outcomes. For example, under JN3, a

provider will receive outcome payments of over $6600 if it successfully gets a

job that lasts at least 26 weeks for a job seeker who has been unemployed for 3

years or more. This will be supplemented by fee-for-service and Job Seeker

Account payments for that job seeker of around $4500 over the three years.[28]

4.39 With continued

long-term unemployment, the role of labour market programs has become even more

important, especially in enabling disadvantaged job seekers to become more

competitive in the labour market and to get a foothold in paid work. Current

programs are performing poorly in this respect.

4.40 Submissions

argued that the long term unemployed and highly disadvantaged jobseekers have

not been well served in terms of quality of assistance delivered and employment

outcomes by the Job Network to date.[29]

Some submissions noted, however, that the reforms under JN3 may go some way to

addressing these problems. Catholic Welfare Australia noted that the intensive

support initiatives under JN3 recognises that providing more active support

earlier in a person's experience of unemployment will have greater potential to

reduce the person moving into long term unemployment.[30]

4.41 Studies indicate

that the employment impact of Job Network programs for job seekers has been

negligible. A DEWR evaluation concluded that Intensive Assistance provided only

negligible benefits for job seekers, and the likelihood of being in employment

three months after completion was increased by only 0.6 per cent.[31]

The Productivity Commission review of the Job Network also found that, using a

variety of assessment methods, the Job Network programs have to date had only a

modest effect on job seekers' chances of gaining employment – 'this finding is

consistent with evaluations of previous Australian and overseas labour market

programs, and is in line with realistic expectations about their capacity to

reduce aggregate unemployment'.[32]

While under the Job Network, intensive services are supposedly targeted to more

disadvantaged jobseekers, some groups have consistently lower employment

outcomes, including older job seekers (aged 55-64 years), those on unemployment

benefits for more than two years, job seekers with less than year 10 education,

Indigenous job seekers and those with a disability.[33]

4.42 A major

objective of the Job Network is to reduce the numbers of long-term unemployed.

Several reports have highlighted the ineffectiveness of Job Network programs on

outcomes for the long-term unemployed. One study noted that long-term

unemployment statistics 'tracked the reduction in unemployment during the

Working Nation period, but there is evidence of persistence in the period

following the introduction of the Job Network, despite strong employment

growth'.[34]

The failure of this system to assist disadvantaged clients is clearly reflected

in the increases in long-term unemployment.

4.43 Several studies

have compared the Job Network with previous labour market programs. ACOSS

stated that employment outcomes for long-term unemployed people under the Job

Network are less favourable compared with the former Working Nation programs.

Another study examined ABS data on unemployment levels for males, females and

long-term unemployed youth and concluded that 'it appeared that these groups

had not benefited as much as under Working Nation'.[35]

While DEWR argued that the Job Network has produced outcomes which are broadly

similar to those achieved under previous labour market programs, the

Productivity Commission noted that labour market conditions at the time of Job

Network have been more buoyant than during Working Nation.[36]

4.44 The BSL stated

that the Job Network's previous funding model provided strong incentives to

focus resources on people who are easy to place rather than those with greater

barriers to employment. By focusing on immediate outcomes, it discouraged

investment in quality services with the potential to address causes of labour

market disadvantage.[37]

Under the recent reforms Job Network services are more outcome focused and the

payment system provides the greatest rewards to those providers who achieve

long-term employment outcomes for their hardest to place clients.[38]

4.45 Evidence to the

Committee suggested a decline in the quality of support provided, a move away

from holistic assistance, and a reduced focus on the broader welfare and

personal needs of jobseekers. The Productivity Commission's review found that

many jobseekers under JN2 received little or no assistance while in Intensive

Assistance – the highest assistance category in the Job Network. The

Commission noted that 'when all the evidence is reviewed, including anecdotal

information provided by job seekers and providers, it still appears that a

significant number of job seekers do not get substantial assistance'.[39]

This led to large numbers of jobseekers being 'parked' – registered with the

provider but provided with no assistance – because the cost of removing

barriers is too high relative to the outcome payment. The Commission noted that

many providers often direct their services to jobseekers that are likely to be

responsive and 'park' those with either insurmountable or high barriers to work.

The former funding arrangements provided weaker financial incentives to provide

assistance to those limited job prospects. The Commission argued that the

Active Participation Model in JN3 is likely to reduce parking problems.[40]

4.46 The Productivity

Commission noted that although Intensive Support under JN3 offers a higher

level of interaction with job seekers, some job seekers with large barriers to

employment may not get much direct assistance from the Job Network. The

Commission suggested that there may be grounds for providing more tailored and

very intensive assistance outside the Job Network to a selective group of job

seekers.[41]

4.47 A further

concern raised in evidence, which may directly affect poverty levels of

disadvantaged jobseekers, is the removal of any notion of job quality from the

achievement of employment outcomes. For example, Job Network providers in the

past received the same payment for placing a job seeker in a low skilled, low

paying job with no prospects for development as for placing someone in a job

offering good training, reasonable pay, and possibilities for career

development.[42]

The new funding arrangements under JN3 do address this problem to some extent

with, for example, higher outcome payments payable to Job Network providers

placing highly disadvantaged jobseekers.

4.48 Active labour

market programs, which aim to improve the 'employability' of young people and

long-term unemployed are only one part of an employment strategy – the other

aspect of this strategy is the need to provide effective links between the

unemployed and sustainable jobs.

Conclusion

4.49 The Committee

notes the concerns expressed relating to the inadequacies of the Job Network in

terms of quality of assistance delivered and employment outcomes for the long

term unemployed and highly disadvantaged jobseekers. The Committee notes that

changes introduced to Job Network arrangements in July 2003 may go some way to

addressing the concerns expressed, especially in providing greater flexibility

and individualised support services to jobseekers, but believes that further

substantial changes to the Job Network are required.

4.50 The Committee

also considers that further measures to address the structural failure of the

labour market to create sufficient employment opportunities need to be implemented

to complement the employment services provided through the Job Network.

Recommendation 3

4.51 That the

Commonwealth Government:

- introduce

a training guarantee for long term unemployed or at risk jobseekers under the

Job Network;

- introduce

quality controls in the form of case management provided to jobseekers;

- provide

automatic entitlement to case management for long-term unemployed people and

unemployed youth;

- provide

caps on the number of unemployed persons a case manager can assist within a job

service environment to reduce the incentive to churn; and

- consider

the feasibility of introducing a 'training and hiring' model (referred to in

paragraph 4.65).

Recommendation 4

4.52 That the

Commonwealth Government introduce a range of measures, in addition to

subsidised employment services, to address structural problems in the labour

market.

Long-term unemployed

4.53 One of the most

disadvantaged groups in Australia is the long-term unemployed. Evidence to the

Committee emphasised that effective employment assistance policies are vital in

order to identify the barriers that are preventing their access to the labour

market and to improve the job prospects of this particularly vulnerable group.

In January 2004, there were 124 500 Australians who had been unemployed

for 52 weeks or more, comprising 21.4 per cent of the total unemployed.

4.54 In Australia,

unemployment rose substantially with recessions in each of the last three

decades. Jobs growth was too weak to reduce it to previous levels in the

ensuing recoveries. This and other factors led to a sharp increase in long-term

unemployment as shown in Figure 4.1.

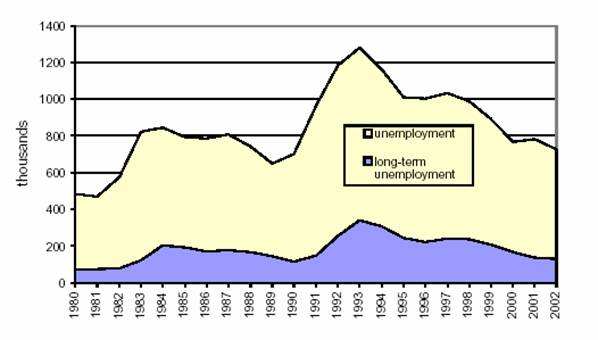

Figure 4.1: Unemployment and long-term unemployment

Source:

Submission No.163, p.105

(ACOSS).

4.55 The length of

time people are unemployed directly correlates with their likelihood of living

in poverty. Some 79 per cent of people who have been unemployed for over a year

live in poverty.[43]

4.56 ACOSS stated

that in February 2003, out of 663,600 people registered for unemployment

benefits with Centrelink, 394,500 people, or 59 per cent, had been registered

for 12 months or longer. This compares with July 1991 when only 23 per cent of

people were registered for over 12 months, indicating a large rise in the

proportion of long-term unemployed over the last decade. Further, of those who

have been out of work for at least a year, the majority have been unemployed

for over two years.[44]

4.57 The long-term

unemployed are much more likely than employed people or short-term unemployed

people to have low education and skill levels, a chronic illness or disability,

to live in a region of high unemployment, and to have an unstable employment

history. Reducing long-term joblessness therefore requires a combination of

strong jobs growth and labour market assistance and training policies to help

these disadvantaged job-seekers to secure a reasonable share of the jobs

created.

4.58 Reducing

long-term unemployment is critical to achieving economic outcomes that are both

efficient and equitable. In general, the longer a person is unemployed the

greater the costs of each additional period of unemployment, both to the person

and to society. Material hardship, and the physiological and psychological

damage resulting from unemployment, are all likely to increase as the duration

of unemployment grows.[45]

4.59 Persistent

long-term unemployment has caused a large group of Australians to live under

extended economic hardship. A high proportion of long-term unemployment among

the unemployed indicates that the burden of unemployment is concentrated on a

relatively small number of people, who often are at risk of permanent

detachment from the labour market.

Skill development and work

experience

4.60 Many submissions

indicated that insufficient attention has been paid to education, training, and

skill development for unemployed people. They argued that more training

assistance should be provided for the long-term unemployed including the

upgrading of numeracy and literacy skills, as well as general communication

skills to enhance their employability. Catholic Welfare Australia proposed that

cash payments should be provided (of $1000 per year of study completed) for

long-term unemployed jobseekers who undertake and complete a recognised course

which will provide relevant skills.[46]

4.61 Submissions

emphasised that effective employment assistance is critical to enabling people

who are unemployed to move into work as early as possible. ACOSS and other

groups argued that there is only limited assistance available to overcome

barriers to work. As noted above, a revised model of employment assistance was

introduced through the Job Network from July 2003. This provides, inter alia,

for the provision of higher level assistance for people who have been

unemployed for one to two years or who are identified as at very high risk of

long-term unemployment. This includes provision of a Job Seeker Account whereby

Job Network providers will be able to purchase or provide assistance for job

seekers to address their barriers to employment.

4.62 Groups argued

that in order to combat the labour market disadvantage facing the majority of

long-term unemployed jobseekers, substantially more assistance is required. The

BSL argued that while the Job Seeker Accounts may improve the situation, the

amount provided for each jobseeker (up to $1200) is still modest.[47]

4.63 Of particular

concern to many is the lack of assistance for those who are the very long-term

unemployed and who fail to get an outcome through customised assistance. After

two attempts at Customised Assistance there is no further substantial

assistance provided. A person who is unemployed for a very long time is so

disadvantaged within the labour market that moving into sustained employment is

unlikely without substantial intervention.[48]

ACOSS argued that an Employment Assistance Guarantee should be introduced

targeting long term unemployed or at risk jobseekers who have not got an

outcome within three months of undertaking Customised Assistance. The Guarantee

would provide incentives for Job Network providers to spend more on appropriate

training and on wage subsidies, and provide job seekers with appropriate help

that they need. The cost would be met in equal part by the provider and the

Government.[49]

4.64 Another gap

identified during the inquiry is the lack of effective programs to provide work

experience for the long-term unemployed. Employers often prefer to appoint

jobseekers with recent work history, and the longer someone is out of work, the

more uncompetitive they become. Work experience can overcome this in part, and

provide on-the-job training in work practices and expectations of employers. A

serious strategy to reduce long-term unemployment must provide for greater

opportunities for paid work experience.[50]

4.65 ACOSS suggested

that a transitional jobs scheme could be introduced, whereby people who have

been unemployed for over two years would be provided with six months employment

at a training wage, and with significant wage subsidies, in the not-for-profit

and public sectors. Wage subsidies would be primarily funded through direct

savings on income support.[51]

The BSL suggested another option could be based on the Swedish 'training and

hiring' model which provides public subsidies to employers who temporarily

release low-skilled workers to upgrade their qualifications as long as they are

replaced by an unemployed person.[52]

Recommendation 5

4.66 That a

transitional jobs scheme for the very long term unemployed be introduced,

whereby people who have been unemployed for over two years would be provided

with six months employment at a training wage in the not-for-profit and public

sectors.

4.67 Submissions also

argued that targeted policies to reduce the cost to employers of employing long-term

unemployed and disadvantaged jobseekers, for example, by way of direct subsidies,

tax exemptions or rebates need to be developed. These need to operate over a

reasonably long timeframe, as employers tend not to respond to short-term

incentives.[53]

The working poor

4.68 Until relatively

recently to be in paid work but poor used to be a contradiction in Australia.

In the 1970s, the Henderson poverty inquiry found that less than two per cent

of families with an adult in full-time employment could be described as poor.

Rather, poverty was mainly a problem for those who could not get waged work. Since

the 1990s, however, having employment is no longer a guarantee of staying out

of poverty. The phenomenon of the 'working poor' refers to the situation where

households fall below a defined poverty line even when family members are in

paid employment.

4.69 ACOSS stated

that some 365,000 Australians were living in 'working poor' households in 2000.

These are families and single people whose main source of income is wages and

salaries but whose incomes are below the poverty line, using the before-housing

half average income poverty line. Although this represented just 3.2 per

cent of people living in such wage-earning households, it represented 15 per

cent of all people living in poor households.[54]

4.70 Worsening wage

inequality is a major contributor to the widening social divisions in society.

This problem has been exacerbated by the increasing numbers of people unable to

secure full time permanent work and forced to take casual and part time jobs. [55]

A Smith Family study showed that the risk of poverty for those working either

full-time or part-time increased slightly over the decade 1990-2000. While 10.7

per cent of all Australians working part-time were in poverty in 1990, by 2000

this had increased to 11.7 per cent. For wage and salary earning families there

was a marginal increase in the risk of being in poverty in all four earnings

category (namely, one part-time earner, one full-time earner, two earners – at

least one part time – and two full-time or three earners) over the

corresponding decade.[56]

Another study commissioned by the Smith Family found that one in five poor

Australians live in a family where wages and salaries are the main source of

income.[57]

4.71 The demographic

characteristics of low-paid workers show that women, workers with no

post-secondary educational qualifications and younger workers are

overrepresented in this group. One study found that whereas 45 per cent of all

wage and salary earners are women, they make up 54 percent of low paid workers.

Almost half (46 per cent) of low paid employees are persons who had left school

before completing secondary school. Also, younger adults, those aged under 30

years, have a higher representation in the low paid group than older workers.

As to geographical location, workers living in rural areas and small urban centres

were more likely to be in low paid jobs. Persons born in a non-English speaking

country also have a slightly higher likelihood of being in low paid employment.[58]

4.72 Severely limited

opportunities are often part of the life experiences of low wage working poor

individuals and their families. A lack of financial resources often has adverse

flow-on effects for workers and their families. A lack of money can led to

reduced access to preventive health and other services; reduced educational

opportunities for their children and a disincentive for them to participate in

post-secondary education; and a reduced ability to participate in social

activities and in the wider society generally. Lack of financial resources also

reduces a worker's asset base with more likelihood that their financial

difficulties will persist into old age.

4.73 A study by

Eardley examined the growth of the 'working poverty' in Australia from the

1980s to the mid 1990s using ABS survey data.[59]

Although there are many different measures of low pay in the literature, the

most widely used approach is to define an hourly earnings threshold level which

reflects the level of remuneration for work undertaken in a job. A person

earning under this cut off is deemed to be working for low pay. The study defines

'low pay' as two-thirds of the median hourly rate for all waged workers. The

measure included both men and women, and full-and part-time employees.

4.74 The study found

that the phenomenon of working poverty in Australia is an increasing problem

with the proportion of low-paid workers who are also in poor families

increasing to about one in five in 1995-96. Only part of this is due to the

increasing prevalence of involuntary part-time and casual work. In 1981-82, one

in ten low-paid adult employees lived in poverty, as defined by the Henderson

poverty line – this had increased to one in five by the mid-1990s. The growth

in poverty among those in full-year, full-time work appears to have risen

significantly, with a particular increase among single person households. While

the unemployed as a group are still more likely to live in poor families than

even low paid employees, employment seems to be becoming a much less effective

safeguard against poverty than in the past.

4.75 The current

system of enterprise bargaining severely disadvantages low-paid workers. The

Australian Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Workers Union (LHMU) stated

that bargaining at the enterprise level is most suited where workers are

employed in large enterprises providing long-term employment in fixed

locations. This does not exist in many service establishments which are

characterised by indirect employment relations, the dispersal of workers in the

same industry across many establishments, and high rates of casualisation and

turnover. In addition, subcontracting makes enterprise bargaining difficult

because the employer for whom workers perform their labour is not the direct

employer with whom workers are legally able to bargain.[60]

Life for the low paid

4.76 The Committee

received a substantial amount of evidence during the inquiry from many

individuals in low wage employment. The personal experiences of these people

provided a very valuable insight for the Committee about the difficulties faced

in making ends meet and providing for themselves and their families. Some of

these individual case studies are provided in the box below.[61]

4.77 This evidence of

these people indicated that for low paid employees:

- finances are always tight;

- expenditure is modest and overwhelmingly on necessities (food,

clothing, housing and utilities); and

-

there is an ever present financial stress, which requires the low

paid to carry a level of debt in order to make ends meet and to go without

things and activities associated with full and active participation in society.

The working poor – doing

it tough

Ms McScheffrey – I

am 31 years of age. I am in a de facto relationship, with three children

under 10. I currently work at the Flinders Medical Centre Community Child Care

Centre as a child-care worker and I have been there for 10 years. I am

also an LHMU member. I work on a casual rate because I choose to, as I will get

more money per hour, $15.35 an hour doing 24 hours a week, and I forgo my sick

leave and holiday pay as I am better off getting the extra hourly rate.

We used to get a health care card. We no longer do,

because my partner's and my combined income is $50 over the limit. Due to not

having a health care card, we get no help with school fees and have to pay the

full doctors fees, as there is no bulk-billing in my area. The family payment

system does not seem to support families where both parents are part-time or

casual. We have inadvertently incurred family allowance debts because we have

to estimate our future incomes, and quite often have had to pay back. A number

of times we could have been eligible for parenting payment but have not

bothered to fill out the forms because it is too much hassle to fill them out

and it is only for one or two fortnights. The next fortnight you are not

eligible for it. You get knocked off. You have to go back and fill the forms

out again.

My life

could be worse, but when I see people like CEOs and managers earning so much

money, obviously the money is there for us to be paid better so that I could

afford to take my children on holidays, to go to the movies et cetera and

to do household repairs, and maybe to run two cars. I would like the committee

to look into the reasons why, if the money is there to pay CEOs and managers

such large amounts of money, low-wage earners cannot have a better lot.

Committee Hansard 29.4.03, p.5 (Ms McScheffrey).

Ms Parajo – I work at the Sheraton on the Park, and I am a LHMU delegate there. I have

worked at the hotel for almost nine years. My job is in the uniform and/or

valet attendant area. I receive approximately $306 per week after tax. I work

approximately 21 hours a week. I have five dependent children between the ages

of two and 13. I am a single parent, unfortunately. I would like to work more

hours a week, but I cannot manage due to my parenting responsibilities. In any

case, I try to work every second weekend just to get extra money from the

penalty rates to help pay the bills. I am sorry, but I am a bit upset. I cannot

remember the last time I was able to take a break or to have a holiday.

I find it very difficult to manage my basic costs such

as clothes, health, transport and education. The living wage pay rise I receive

is so small. It is a bit of help, but it needs to be bigger to make any real

difference. What can the committee do to make sure that in any future pay

increase I receive real help? I have been forced to take unpaid leave for the

birth of my children. This has forced our family into financial hardship. What

can the committee do to make sure that working families do not continue to suffer

when children arrive? Can you ensure that paid maternity leave becomes a right

for all workers, especially the low paid, especially us? We are working for

peanuts.

Committee

Hansard 26.5.03, p.318 (Ms Parajo).

Mrs Dewar – I

work in the bar and in food preparation at the Queensland Turf Club and the

Brisbane Lions Club at the Gabba. I enjoy the customers and the social

interaction in hospitality. I am a casual worker. I used to work two shifts at

the Queensland Turf Club, a mid-week shift and a Saturday shift. I had worked

at the turf club for seven years and I had had these shifts for two years when

the manager took me off the mid-week shift. This left me with only one shift at

the turf club and one shift at the Brisbane Lions Club. I now take home $160 a

week. I also receive some money from Centrelink. Losing a shift is a lot to

someone who is on their own and relying on this money. You do not have any

choices when you are casual. You do not want to cause trouble. Managers can

make decisions based on personality instead of on work ethic, and they do this

all the time. I am an honest and hard worker. It is not because of my work that

I lost this shift; it is because of favouritism and personalities.

I am on my own...I am 54 years of age, and I would like

to retire by the time I am 60. It is difficult to be on your feet all day. I

feel like I have done the hard work in life, but I have no option but to stick

it out.

I manage on the income that I get. I put away anything

extra that I can. I am currently paying off my house, but it is getting hard

because everything is going up. It is getting harder to manage day to day. I

cannot afford a car, and it takes me 1½ hours to get from Green Meadows to Ascot because I

need to get a few buses. I also cannot afford to go on holidays. Casuals in

hospitality have no security. We want to be treated fairly. I would like to

ask: what can the government do to make sure that we can keep our shifts and

that we have as much security as other people?

Committee

Hansard 4.8.03, p.1143 (Mrs Dewar).

4.78 The ACTU

commissioned a study, based on HES data, on the financial stress experienced by

households whose principal source of income is employee income. The study

provides empirical evidence of the financial struggle experienced by 'working

poor' households. The data for the first quintile households is provided below.

The working poor – survey

of financial stress

- When asked about the management of

household income the majority of households – 58.5 per cent or 477,477

households – responded that they just managed to break even most weeks while a

further 17.9 per cent (146,100 households) said they spend more money than they

get. That is, more than three quarters of the first quintile households are

just breaking even or are spending in excess of their income.

-

When asked to compare their

standard of living with two years ago, 69.2 per cent or 564,810 households said

it was worse (27 per cent) or the same (42.2 per cent). Only 27.3 per cent felt

their present standard of living better than 2 years ago.

- 34.9 per cent or 284,854

households said the reason they had not had a holiday away from home for at

least one week per year was that they could not afford to.

- 29.9 per cent or 244,044

households indicated that they had experienced cash flow problems in the past

year.

- When asked if they could raise

$2,000 in an emergency 26.0 per cent or 212,212 households reported that they

could not.

- 22.0 per cent or 179,564

households said they could not afford to have a night out once a fortnight.

-

20.4 per cent or 166,505

households reported having not paid utilities bills due to shortage of money,

and 10.3 per cent responded that they had not paid registration or insurance

bills on time due to shortage of money.

- 14.6 per cent or 119,165

households said they could not afford a special meal once a week.

- 14.2 per cent or 115,900

households said the reason some members of the household bought second hand

clothes is that they couldn't afford to buy new ones. The same proportion –

14.1 per cent said they had sought financial help from friends or family due to

shortage of money.

- 11.5 per cent or 93,863 households

said that the reason members didn't spend time on leisure or a hobby activity

is that they couldn't afford to.

- When asked about the main source

of emergency money 17.7 per cent or 144,467 households responded that they

would need to rely on a loan from family or friends. A further 15.6 per cent

would need to rely on a loan from a bank/building society/credit union, and 9.2

per cent a loan on a credit card.

Submission

94, pp.12-14 (ACTU).

4.79

The evidence indicates that for low paid, low income working families

life is a struggle involving significant levels of financial stress and

disadvantage. It also shows a lack of capacity to participate socially in

activities enjoyed by others.

Addressing the problem of low pay

4.80 The Australian

Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Workers Union (LHMU) argued that the

low-wage labour market has emerged through the intersection of two processes,

namely:

-

the precarious organisation of much service work, with short and

inadequate hours, casual work, 'casualised' part-time work, short job tenure,

contracting and undervalued, insecure employment; and

- the restructuring of the industrial framework to benefit

enterprise and 'individual' bargaining over industry standards, with a

diminished 'safety net' of low wages.[62]

4.81 The LHMU added

that the low-paid labour market is characterised by the interlocking dynamics

of low pay – low hourly rates of pay and fragmented work experiences that

provide inadequate, insecure levels of employment. In the low-paid labour

market, many workers who may receive reasonable hourly rates of pay are

nonetheless unable to secure adequate weekly or yearly work to constitute a

liveable wage. The union noted that the consequences of an entrenched low-paid

labour market 'go beyond employment. These consequences include poverty,

inequality and disadvantage'.[63]

4.82 As discussed in

chapter 3, poverty is increasingly associated with low pay. The LHMU stated

that, in fact, the low-paid and the jobless poor are often the same people at

different stages in their lives, 'churning' through a series of poorly paid

jobs and spells of unemployment. In addition, thousands of poor individuals,

including children, rely on the precarious incomes of low-paid workers.[64]

4.83 During the

inquiry a number of options were suggested to address the problem of low paid

workers. These issues are discussed below.

Raising minimum wages

4.84 A number of

organisations, including the LHMU, argued that there was a need to raise

minimum wages for low paid workers. The union argued that:

Achieving fair wages in our society in part depends on our

ability to raise wages at the bottom of the labour market. We must ensure that

low-paid workers enjoy the gains of the labour market as a whole.[65]

4.85 In order to

raise minimum wages the LHMU argued that it would be necessary to establish an

adequate income benchmark. The LHMU pointed to research conducted by the Social

Policy Research Centre which calculated a 'modest but adequate' benchmark for a

range of household types to achieve an adequate standard of living relative to

contemporary community standards. Australia has not had a minimum wage

calculated on an analysis of household budgets since the Basic Wage, derived

from the original Harvester judgement, was abandoned in 1967.[66]

4.86 ACOSS argued

that the Australian Industrial Relations Commission should establish a new

minimum wage benchmark based on a wage level that enables a single full-time

worker to live in 'modest comfort' and to participate in contemporary society.

This should be set well above the poverty income level for a single adult.[67]

4.87 Minimum

full-time wages have fallen well behind average wages over the last 20 years,

especially in the early years of the shift towards enterprise bargaining,

before the present round of 'Living wage' cases was instituted in 1996. The

minimum wage has now fallen to just 50 per cent of average earnings, a

reduction of 15 per cent since 1983.[68]

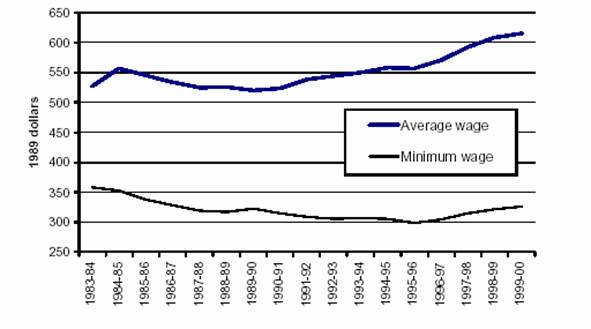

Figure 4.2: Real average and minimum wages – 1983-1999

Source: Submission

163, p.117 (ACOSS).

4.88 The ACTU also

stated that there has been an ongoing decline in the relative value of the

Federal minimum wage over the course of the last decade, and particularly since

1996. The ACTU added that:

...the minimum rates adjustment process...concluded some time round

the early nineties, depending on which awards and classifications you are

talking about. Since that time, there has been an ongoing decline. An indicator

of that is that the federal minimum wage is now, for the first time, worth less

than half of average earnings. It has dropped to 49.9 per cent of average

earnings.[69]

4.89 There is

continuing debate over whether higher minimum wages lead to higher

unemployment. The empirical evidence as to whether low paid workers are priced

out of the labour market due to higher minimum wages is equivocal. An OECD

study concluded that higher minimum wages are not a major cost on jobs, at

least in the case of adults but they do seem to have more of an impact on youth

employment. Other studies have reported that there is no clear evidence either

way that higher minimum wages affect employment levels.[70]

Recommendation 6

4.90 That the

Australian Industrial Relations Commission establish a new minimum wage

benchmark based on a wage level that enables a single full-time worker to

achieve an adequate standard of living relative to contemporary community

standards.

4.91 The Committee

believes that the establishment of a new minimum wage benchmark is the

foundation of a strong award system. It is essential that a new benchmark be

established on top of which relativities/margins are calculated.

4.92 The LHMU also

argued that once a fair benchmark for minimum wages is established, the wages

of the lowest paid workers should be linked with wages growth in the rest of

the labour market. In addition, the LHMU argued that there should be a new

commitment to restrain the excessive wages of the highest paid executives and

managers – 'it is unjust that only the wages of the lowest-paid workers are

subject to community scrutiny and wage restraint'.[71]

Tax credits

4.93 Some submissions

argued for the introduction of tax credits to address the issue of low wage

work. Catholic Welfare Australia pointed to the UK Working Families Tax Credit

Scheme (WFTC) and the US Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) Scheme as possible

models that could be adapted to Australian conditions. The EITC and WFTC

provide tax refunds to low income families that derive their income primarily

from wages, rather than welfare. As household income increases from employment,

the tax credit is reduced. Catholic Welfare Australia argued that tax credit

schemes would reduce the effect of high effective marginal tax rates on low

income households.[72]

4.94 The BSL noted

that while tax credit schemes have some merit, they have significant

limitations. The BSL submitted that:

An EITC would effectively mean that government replaced

regulation with business welfare as a means of protecting low-paid workers. It

would also provide a subsidy regardless of employers' capacity to pay better

wages, and possibly result in a longer term effect on employer expectations,

with government seen to have primary responsibility for the adequacy of

workers' incomes.[73]

4.95 The LHMU was

opposed to the use of targeted tax credits to raise the incomes of low-paid

workers, arguing that 'such measures respond to the failure of the industrial

system to produce adequate incomes by shifting the responsibility for pay from

firms to the government'.[74]

The union argued that tax credits contribute to the expansion and entrenchment

of the low-wage labour market – 'the answer is not to ask the social security

system to accommodate the failure of the industrial framework to deliver fair

pay, but rather to reimagine how we can provide decent work with fair wages and

adequate, secure employment'.[75]

The LHMU argued that a system of tax credits entrenches low-paid work by

artificially suppressing wages – employers no longer have to provide a liveable

wage to attract potential employees, because the government makes up the

difference in the pay rates.

4.96 The Committee

does not favour the introduction of tax credits to address the issue of low

paid employment. Such measures provide a subsidy to low-wage employers and are

likely to expand the pool of low-wage jobs. It is essential that low paid

workers not become entrenched in a low-wage labour market. The Committee

considers that it is the role of the industrial relations system to ensure an

adequate wage for employees and not shift the responsibility to government. As

noted above, the Committee favours an approach that will raise minimum wages.

Pay rates are, however, only one of the dynamics driving low pay. Issues

surrounding the precariousness of work that many low-paid employees face also

need to be addressed.

Precariousness of work

4.97 The LHMU and

other unions argued that mechanisms need to be developed to address the

precariousness of work for those in low paid occupations to ensure adequate,

secure employment conditions. Concerns raised included:

- the increase in short hour jobs;

-

increased casualisation;

- wages and conditions in the personal services sector; and

- the problems of contract labour.

4.98 The LHMU argued

that action needed to be taken to address the problem of the proliferation of

short hour jobs. The union stated that thousands of its members and other

low-paid service employees work short hours due to the organisational structure

of particular industries. The LHMU stated that:

At present, employers can offer workers short and variable hours

without redress. They can choose to employ any proportion of their staff as

casuals and without any job security, without certainty of hours and therefore

pay, and without leave entitlements.[76]

4.99 The LHMU told

the Committee that it is addressing the issue of short hour jobs by seeking to

increase minimum starts. The union added that:

One of the ways we can do that in the area of award regulation

is minimum starts. At the moment in the cleaning industry, for example, most of

the awards provide for a two-hour minimum start; that is to say the shortest

period that you can actually work is two hours. In our view that is

inadequate...So we are campaigning around increasing those minimum starts.[77]

4.100 The LHMU argued

that working conditions in these industries must include a workable floor on

the minimum hours which workers are offered by employers.

4.101 Submissions also

argued that there needs to be greater employment security through reduced

casualisation. The LHMU noted that at present employers can transform secure,

permanent employment into casual work with almost no redress. Some 30 per cent

of working Australians are casuals and in some industries, such as the

hospitality sector, the proportion is double this figure – 'limiting

casualisation must be a priority within any effort to provide decent work in

this country'.[78]

This issue is discussed later in the chapter.

4.102 In addition, the

LHMU argued that it was important to ensure that employers who receive

Government funding to deliver personal services, such as in the aged care

sector, pay adequate wages in order to reduce staff turnover and provide for

continuity of care. The union argued that at present, both public and

non-profit providers can use Government funds to employ care workers in

sub-standard conditions. The union suggested that there was a need to attach

wage and condition standards to public funds used for care and support work.[79]

Conclusion

4.103 The evidence

received during the inquiry has raised a number of important and complex issues

relating to low paid employment. The Committee believes that the issues raised

warrant an inquiry by the Commonwealth Government to fully address the concerns

raised. The Committee notes that the LHMU argued that there was a need for an

inquiry into the question of low pay – 'and that is something that we intend to

address over the next couple of months in the lead up to the ACTU congress and

the next [national wage] case'.[80]

Catholic Welfare Australia also called for an inquiry into low-paid employment.[81]

Recommendation 7

4.104 That the

Commonwealth Government conduct an inquiry into low-paid employment and that

this inquiry examine:

- the nature and extent of low-paid employment in Australia;

- the introduction of a workable floor in relation to the minimum

hours of work offered by employers;

- the problem of casualisation and employment security;

- the feasibility of attaching standards in relation to wages and

conditions to Government funding of services; and

- the wages and conditions pertaining to contract labour.

Casualisation

4.105 Evidence to the

inquiry, as noted previously, commented on the trend towards increasing 'casualisation'

of the workforce and the use of 'labour-hire' employees and the adverse

implications these developments are having on the pay and working conditions of

workers.[82]

4.106 There has been a

marked increase in casual employment, especially over the last decade. Between

August 1988 and 2002 total employment of casual workers in Australia increased

by 87.4 per cent (141.6 per cent for men and 56.8 per cent for women). By

August 2002 casual workers comprised 27.3 per cent of all employees, an

increase of 7 percentage points since August 1991.[83]

4.107 This form of

employment has been most often associated with teenage and female labour

markets, however, the increase in casual employment during the 1990s was due to

the rapid growth in this form of employment among all types of workers,

especially among males and young adults. While levels of casualisation

increased for all age groups they have been most pronounced for younger workers

aged 15 to 24 years.[84]

4.108 There is no

standard number of working hours that defines a casual worker. Consequently,

casual workers can be employed on either a full-time or part-time basis. Casual

employment is most prevalent in the part-time labour market, accounting for

73.6 per cent of all male part-time jobs and 55.3 per cent of all female

part-time jobs. By August 2002, casual part-time employment as a proportion of

total employment was equal to 18 per cent. Permanent full-time employment

accounted for 61 per cent of total employment – 6.9 percentage points lower

than the corresponding share in 1994.[85]

4.109 The main

difference, at common law, between a permanent and a casual worker is that a

permanent employee has an ongoing contract of employment of unspecified

duration while a casual employee does not. The main characteristics of casual

employment that flow from this are:

-

limited entitlements to benefits generally associated with

continuity of employment such as annual leave and sick leave; and

- no entitlement to prior notification of retrenchment (no security

of employment) and only a limited case for compensation or reinstatement.[86]

4.110 Most casual

workers are concentrated in a few occupations, and these tend to be relatively

low skilled – the retail trade, hospitality, property and business services,

and health and community services. Other industries, such as manufacturing,

construction and education also have sizeable concentrations of casual workers.

4.111 Casual employees

do not necessarily have only a short term employment relationship with their

employer – many remain with their employer for a considerable length of time.

ABS data for 2001 indicate that 54.4 per cent of casual employees had been in

their jobs for a year or more.[87]

4.112 Evidence

commented on the insecure and irregular nature of this type of employment and

its lack of 'job quality'. Submissions and other evidence indicated that, in

comparison with permanent workers, casual workers:

- have less job security;

- are less likely to have set hours on a weekly, fortnightly or

monthly basis;

- have less say in start and finishing times;

- work less hours per week;

- are more likely to be on-call or stand-by;

- are less likely to be covered by workers compensation insurance;

- have very low rates of union membership;

- are less likely to receive training, particularly formal

training;

- are more likely to be paid by a labour hire firm;

- earn considerably less than permanent employees;

- contain a large proportion of workers wanting more hours or set

hours;

- are likely to have no guarantee for the number of hours they work;

and

-

are more likely to have variable earnings.[88]

4.113 Evidence

highlighted the 'poverty dimension' of casual employment, noting that these