Background

The illegal wildlife trade

2.1

The trade in elephant ivory and rhino horn is part of the global illegal

wildlife trade, worth an estimated US$7 to US$23 billion per year.[1]

This trade is facilitated by the activities of organised crime groups, along

with rebel militia and terrorist organisations that operate through established

criminal networks.[2]

2.2

The linkages between the illegal wildlife trade and other crime types

are well established. Environmental investigator, Mr Luke Bond, commented that

almost all operational activities in which he has been involved have had links

to other crime types.[3]

IFAW reported organised crime groups direct wildlife crime profits towards

other illicit activities such as human trafficking, drug manufacturing and

money laundering.[4]

The illegal wildlife trade is also complex: the Jane Goodall Association,

referencing research by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC),

explained that the market is nuanced, with each commodity having its own market

demand, network and actors involved.[5]

2.3

Despite efforts to address wildlife crime globally, the UNODC submitted

that wildlife crime has grown over the last decade into a 'significant and

specialised area of transnational organised crime', driven by high consumer

demand and 'facilitated by generally inadequate law enforcement response, low

prioritisation as a serious crime, weak legislation, and non-commensurate

penalties'.[6]

Further, the illegal trade exists alongside the legal supply chain, enabled by

corrupt officials, fraud and inadequate regulation.[7]

2.4

The illegal wildlife trade is a global problem, and a significant threat

to many plant and animal species. Elephant ivory and rhino horn are just two examples

of wildlife that is traded illegally. The global seizure database 'World Wise' reveals

that between 1999 and 2015 there were over 164 000 seizures of wildlife from

120 countries. Of those seizures, there were almost 7000 species seized,

including mammals, reptiles, corals, birds and fish.[8]

In Australia, there are approximately 7000 wildlife items detected by customs

officials each year, along with ongoing reports of wildlife trafficking cases

that implicate Australian nationals.[9]

The illegal trade in elephant ivory and rhino horn

Elephant ivory

2.5

Elephants are hunted primarily for their ivory tusks. Once removed, the

ivory is used in furniture, musical instruments and for ornamental purposes. Some

regard ivory as a highly valued item. In both western and eastern cultures, it

has been seen as a status symbol for wealth and power, particularly in China

where the 'nouveau riche' view ivory as 'white gold'.[10]

Although increasingly becoming a taboo object in western society, it remains

highly sought after in Asia.

2.6

The price of raw ivory is variable, depending on demand in the

international market. This demand is largely driven by the Asian market, in

particular, China. In 2011, there were over 11 000 ivory pieces sold in the

Chinese auction market, worth a total of US$94 million, a 170 per cent increase

from 2010.[11]

Since China announced its plan to implement a domestic ban in 2012, the price

of ivory has declined across Asia and resulted in the Chinese people no longer

viewing ivory (and rhino horn) as an inflation-proof investment.[12]

The UNODC reported that the price at one stage reached $1000 per kilo, whereas

latest figures have shown the price has dropped to approximately $600 to $700

per kilo.[13]

Evidence suggests that ivory traffickers are stockpiling ivory for price

speculation purposes.[14]

2.7

The Department of the Environment and Energy (DoEE) informed the

committee that raw ivory is primarily trafficked from Africa to Asia (predominantly

destined for South East Asia and China) in large sea cargo shipments (between

500 and 800 kilograms)[15]

by transnational organised crime groups. Approximately 10 per cent of

poached ivory is seized, which according to the DoEE provides 'a good

indication of not only the effectiveness of the enforcement regime around the

world but also where the main routes are'.[16]

2.8

The UNODC's 2016 World Wildlife Crime Report demonstrated the

main flows of raw ivory between 2007 and 2014, based on raw ivory seizures. It

identified source, transit and destination of shipments. Australia was recognised

as a jurisdiction with less than 1000 kilograms of seized ivory, whereas China

seized over 41 900 kilograms in total.[17]

Figure 1 shows the international flows of raw ivory from the 2016 UNODC report.

Figure 1: Main flows of raw ivory seizures (kilogram), 2007

to 2014:[18]

2.9

According to the UNODC, based on available data, Australia is not a

major transit or destination country, which is a view shared by the DoEE.[19]

2.10

There are two species of elephants: the African elephants found across

sub-Sahara Africa; and the Asian elephant found in 13 Asian countries. Both

species have experienced significant population declines since the early 20th

century, primarily due to poaching and habitat decline and degradation.

African elephants

2.11

Elephant numbers in African have rapidly declined over the past century,

with their population once estimated to be five million.[20]

The Great Elephant Census (the Census)[21]

estimated that in 2016 there were 352 271 elephants living across the 18 countries

surveyed. It found African elephant populations have declined by 30 per cent

between 2007 and 2014 (equal to 144 000 elephants), with an estimated decline

of eight per cent each year, chiefly due to poaching.[22]

Approximately 20 000 African elephants are killed each year across the

continent.[23]

2.12

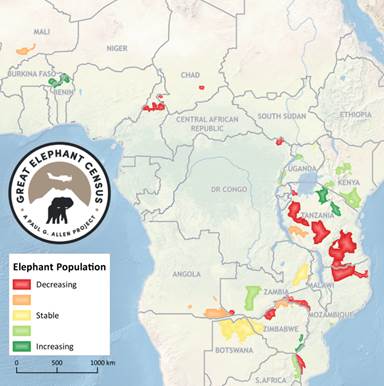

Figure 2 details surveyed countries and the status of their elephant

populations between 2007 and 2014. It shows that stability of elephant

populations, even in different regions of the same country, vary drastically.

For example, most of Tanzania is witnessing a decline in elephant populations,

whereas the northeast area of the country has seen population increase.[24]

Figure 2: Elephant population trends across Africa over the

past ten years based on Great Elephant Census data and comparable previous

survey:[25]

2.13

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies

the African elephant as a vulnerable species. This assessment is due to

population numbers varying across the region. In 2007, the IUCN reported that

elephant populations in eastern and southern Africa were increasing by an

average rate of 4 per cent per annum.[26]

2.14

Current trends indicate that if poaching is not adequately addressed,

then it is likely that elephant populations will disappear from some countries in

Africa. For example, Tanzania, which once had the second-largest elephant

population, went from 100 000 elephants to 40 000 elephants in a five year

period.[27]

Asian elephant

2.15

The Asian elephant (also known as the Indian elephant) is listed as

endangered by the IUCN. In 2008, the IUCN reported that its population size had

decreased by 50 per cent over the past 20 to 25 years. In 2016, CITES estimated

that the current population was between 30 000 and 50 000,[28]

with at least 25 per cent of the population now living in captivity.[29]

2.16

The Asian elephant has become extinct in West Asia, Java, and a large

proportion of China. Populations remain in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal,

Sri Lanka, Cambodia, China, Indonesia (Kalimantan and Sumatra), Laos,

Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand and Viet Nam.[30]

2.17

Unlike African elephants, which are hunted primarily for their ivory,

Asian elephants are mostly hunted for their meat and leather.[31]

However, the UNODC reported in recent years there has been a sharp increase in

the killing of Asian elephants with both their skin and ivory removed.[32]

Rhinoceros horn

2.18

Rhinoceros horn was traditionally used to adorn weaponry, but today it

is primarily sought for its supposedly medicinal properties in traditional

Chinese medicine, and ornamental appeal. Although its medicinal value has been

disproven, and is not endorsed by Chinese medicine advocates,[33]

its value as both a medicine and ornament (as a status symbol) remains.[34]

In 2011, Chinese auction houses sold 2750 pieces of rhino horn carvings worth a

total US$179 million, a 111 per cent increase from 2010. According to IFAW, the

average price for a rhino horn piece during that time was US$177 000.[35]

2.19

Although the sale of rhino horn is less common in Australia, records

collated by IFAW revealed rhino horn items being sold for up to AU$207 400 in

2011,[36]

and between 2007 and 2017 the average price of 70 listed rhino items sold at

auction was AU$51 736.[37]

2.20

There are five species of rhino, two of which are found in Africa and

the remaining three are found in Asia. There are two species of African

rhinoceros, the black rhino and the white rhino. The black rhino is found

throughout the southern and eastern parts of Africa, whilst the white rhino,

which is separated into two subspecies, is located in both the north and south

of Africa.

White rhinoceros

2.21

The white rhino is the most prevalent species of rhino in the world,

with an estimated 19 682 to 21 077 individuals. However, the white rhino is

split into two subspecies: the northern white rhino and the southern white

rhino. The northern white rhino is critically endangered and was declared

extinct in the wild in 2008.[38]

There remain only two female northern white rhinos in captivity after the last

male, named Sudan, died in March 2018.[39]

2.22

The southern white rhino is classed as near threatened by the IUCN due

to the ongoing and increasing threat of poaching. The vulnerability status of

individual populations varies depending on protection granted under each

jurisdiction, and the IUCN warns that in the absence of conservation, the

southern white rhino will become a vulnerable species within five years.[40]

According to IFAW, in 2017 there were 1028 rhinos killed for their horns in

South Africa, equating to three per day.[41]

Black rhinoceros

2.23

The black rhino population, once regarded one of the most numerous rhino

species in Africa (several hundred thousand across the continent), started to

experience significant population decline in the 19th century. By

1970, the black rhino population had reduced to 65 000 animals. In 1992, its

population further declined by 96 per cent, to approximately 2400 rhinos.[42]

Today, the IUCN classifies the black rhino as critically endangered,[43]

with a population of between 5040 and 5458 rhinos.[44]

Greater one-horned rhinoceros

2.24

The greater one-horned rhino or the Indian rhino is found in India and

Nepal and is primarily threatened by human harassment and encroachment on its

habitat. Its population reached a low of 200 in the last century, but through conservation

efforts has increased to 3500 today.[45]

2.25

The IUCN lists the greater one-horned rhino as vulnerable due to the

strict protection granted by the Indian government. Populations in Nepal and

north-eastern India are decreasing due to habitat decline.[46]

Sumatran rhinoceros

2.26

The Sumatran rhino is found in parts of Southeast Asia, primarily in

Sumatra, Indonesia. According to research, the Sumatran rhino has experienced

ongoing population decline for the last 9000 years and was believed to number

only 800 in 1986. Today it is estimated that there only remains between 30 and 100

surviving in the wild.[47]

2.27

The IUCN lists the Sumatran rhino as critically endangered. It

anticipates that its population will continue to decline due to a lack of a

subpopulation exceeding 50 animals needed to sustain population growth.[48]

Javan rhinoceros

2.28

The Javan rhino is found on the island of Java, Indonesia. It is

incredibly rare, and with a population of less than 67, it is unable to sustain

long-term survival. Poaching and habitat loss, along with inbreeding, are

primary causes of its population decline. Conservation efforts are focused on

re-establishment programs, to rejuvenate threatened populations.[49]

2.29

The IUCN classifies the Javan rhino as a critically endangered species,

and similar to the Sumatran rhino, its population is below the required threshold

to facilitate population growth.[50]

International trade regulatory framework

2.30

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wildlife

Fauna and Flora (CITES) was agreed on 3 March 1973 and entered into force on

1 July 1975.[51]

Its purpose is to 'ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals

and plants does not threaten their survival',[52]

and protects over 35 000 species of animals and plants.[53]

2.31

CITES parties are required to establish a CITES management authority,[54]

which is responsible for the application of CITES in each jurisdiction. A CITES

management authority is empowered to: issue import, export or re-export permits

and certificates of origin that enable a listed specimen to enter or leave the

country;[55]

communicate information to CITES parties and the CITES secretariat; and report

on compliance matters and contribute to CITES annual reports.[56]

2.32

CITES parties determine levels of protection granted to each species,

and are allocated to one of three appendices (Articles III, IV, V of CITES)

according to the degree of protection required.[57]

These appendices are outlined in the following sections.

Appendix I

2.33

Appendix I includes species that are threatened with extinction, and for

that reason, international trade of these species is only permitted in

exceptional circumstances.[58]

A CITES management authority will only issue import/export permits if:

-

the Appendix I specimen is not used for commercial purposes;

-

the movement of the species does not have a detrimental effect on

the survival of the species or movement does not pose a 'risk of injury, damage

to health or cruel treatment';

-

evidence is provided to show the specimen was legally obtained;

and if necessary; and

-

proof of pre-existing import/export permit from a CITES

management authority.[59]

Appendix II

2.34

Appendix II includes species that are not immediately threatened with

extinction, but their trade is controlled to avoid use that may threaten their

survival.[60]

Similar to Appendix I species, certificates from a management authority are

required for the exportation and re-exportation of Appendix II species. The

importer of an Appendix II specimen is required to present either an export

permit or a re-export permit certificate.[61]

Appendix III

2.35

Appendix III includes species that any country has identified 'as being

subject to regulation within its jurisdiction for the purpose of preventing or

restricting exploitation, and as needing the co-operation of other Parties in

the control of trade'.[62]

2.36

All species of elephants and rhinoceros are CITES listed. Both the

African elephant and the Asian elephant are included in Appendix I, except for

African elephant populations[63]

in Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe (Appendix II).[64]All

species of rhinoceros are included in Appendix I, except for the southern white

rhino populations in South Africa and Swaziland, which are included in Appendix

II for purposes of live trade and hunting trophies.[65]

Permits and certificates

2.37

Article VI of CITES details the requirements for the import, export and

re-export permits and certificates issued by the CITES management authority.

These include:

-

time restrictions on the validity of a permit (for example, a

period of six months from the date a permit was granted);

-

measures to prevent the duplication of permits;

-

a requirement for a separate permit or certificate to be issued

for each consignment of specimens;

-

obligations on management authorities to retain records of export

and import permits and certificates; and, if appropriate,

-

an authorisation for management authorities to affix a mark upon

any specimen to assist with its identification.[66]

Exemptions and other special trade

provisions

2.38

There are a number of exemptions under CITES, including:

-

The provisions in Articles III, IV and V of CITES (the

appendices) do 'not apply to the transit or transhipment of specimens through

or in the territory of a Party while the specimen remains in Customs control'.[67]

-

CITES provisions do not apply to a specimen if it was proven to

be acquired prior to that species being listed on CITES (pre-CITES). A CITES

management authority is permitted to issue a pre-CITES certificate that enables

the owner to export or re-export such item.[68]

-

The CITES appendices to not apply to specimens that are

considered personal or household effects in a limited number of circumstances.[69]

-

Appendix I species that were bred in captivity for commercial

purposes (including artificially propagated plant species) are deemed to be

species listed as Appendix II.[70]

-

The export provisions of CITES appendices do not apply if a

management authority is satisfied that an animal specimen was bred in

captivity, is an artificially propagated plant, or part of an animal or plant

bred for commercial use. In these circumstances, a CITES management authority

may provide a certificate 'in lieu of any of the permits or certificates

required under the [CITES] provisions of Article III, IV, or V'.[71]

-

Provisions of CITES appendices do not apply in the following

circumstances:

-

a non-commercial loan;

-

donation or exchange between scientists/scientific institutions

that are registered with a management authority;

-

herbarium specimens (preserved, dried or embedded museum pieces);

and

-

live plant material that has a label issued or approved by a

management authority.[72]

-

A management authority may waive the requirements found under the

appendices to permit the movement of specimens travelling for a zoo, circus,

menagerie, plant exhibition or other travelling exhibition.[73]

The application of CITES in Australia

2.39

CITES is enforceable under the Environment Protection and

Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), which regulates the import

and export of elephant ivory[74]

and rhino horn to and from Australia.[75]

The DoEE is the assigned management and scientific authority of CITES.[76]

2.40

Appendix I specimens can only be imported to or exported from Australia

in exceptional circumstances, or if the specimen has a pre-CITES certificate.

With regard to the importation of pre-CITES specimens into Australia, the DoEE website

states:

...there is no legal requirement to apply for a permit before

importing a specimen that has a pre-CITES certificate from the country of

export. However, [importers] are required to declare the importation, and it is

recommended that you provide a copy of the overseas pre-CITES certificate to

the department. This will ensure that the import is recorded and that the

department has evidence of legal import of your pre-CITES specimen(s) into

Australia. This may be important if you wish to re-export the specimen(s) at a

later stage.[77]

2.41

The DoEE issues pre-CITES certificates in Australia and will do so when

a CITES-listed specimen is exported or re-exported out of Australia. The

exporter must satisfy the DoEE that the specimen is pre-CITES, and can do so by

obtaining provenance documentation, such as:

-

evidence of proof of acquisition and/or origin of a specimen; or

-

a valuation certificate provided by an expert in the field or an

antique dealer, which verifies the age of the item.[78]

2.42

Australia has implemented stricter measures than those found in CITES.[79]

Specifically, stricter domestic measures exist for African lions, cetaceans,

elephants and rhinoceros.[80]

African elephant populations, which are categorised under Appendix II of CITES,

are included in Appendix I under subsection 303CA(1) of the EPBC Act.[81]

Australia has also introduced measures that restrict the trade of rhino

specimens including:

-

the discontinuation of permits being issued to importing rhino

hunting trophies of southern white rhino (Appendix II listed);

-

the ban of rhino hunting trophies being imported as personal and

household effects; and

-

a requirement that radiocarbon dating is compulsory to prove the

age of vintage rhino horn for export.[82]

2.43

For the export or re-export of rhinoceros horn (or products derived from

rhinoceros horn), the exporter must prove the item was obtained before 1975. The

DoEE specifies that satisfaction of this requirement is only met when a

radiocarbon dating result shows the carbon date is pre-1957.[83]

If the result indicates the item was obtained post-1957, the 'margin of error

associated with that result means that there is not a high degree of certainty

that the item was obtained prior to 1975'.[84]

2.44

The importation and exportation of newer elephant ivory and rhino horn

is only permitted in a limited number of non-commercial purposes, such as for

research or a museum exhibition.[85]

2.45

Tables 1 and 2 show the number of imports of ivory[86]

to Australia by number of items and weight, between 2010 and 2015. Table 1 shows

the total number of ivory items imported into Australia over a five year period

was 6455.5. Of this total, the majority (4077 items) were personal items (3769

were imported with pre-CITES certification), and 2101.5 items were imported for

commercial purposes.

2.46

For the same period, the total weight was 78.805 kilograms, split

between personal (32.905 kilograms) and commercial (45.9 kilograms).

Table 1: Imports of ivory (number of items) to Australia,

2010–2015:[87]

Table 2: Imports of ivory (by weight, kilograms) to

Australia, 2010–2015:[88]

2.47

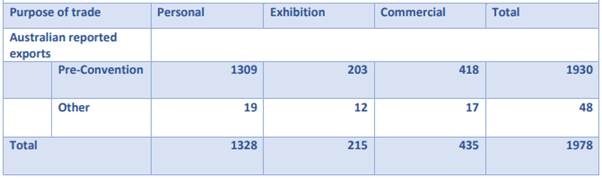

Table 3 and 4 show the total number of ivory items (by number of items

and weight) exported from Australia between 2010 and 2015. Table 3 shows that

there were 1978 items exported from Australia over this period, the majority

(1328) were for personal reasons, followed by commercial (435) and exhibition

(215). Forty-eight of these items were not supported by pre-CITES

certification.

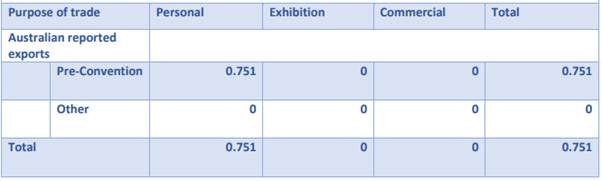

2.48

Table 4 shows ivory exports by weight. The total was 0.751 grams and is

listed entirely as personal items supported by per-CITES certification. Nothing

is listed for exhibition or commercial despite Table 3 indicating that items

were exported.

Table 3: Exports of ivory (number of items) from Australia,

2010–2015:[89]

Table 4: Exports of ivory (be weight, kilograms) from

Australia, 2010–2015:[90]

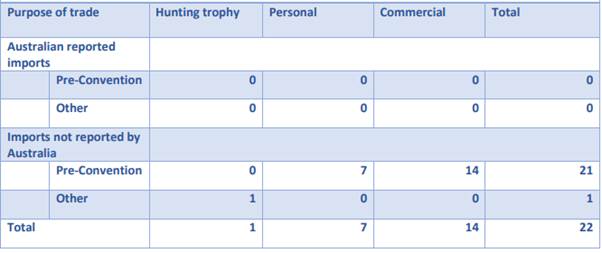

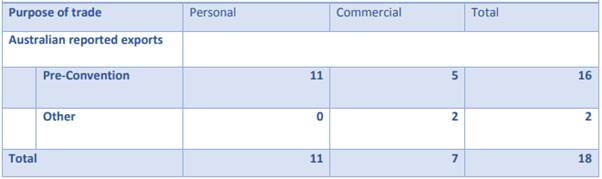

2.49

Table 5 shows the number of rhino horn items imported into Australia

between 2010 and 2015. There were 22 items in total, 14 of which were for

commercial purposes, seven for personal use, and one item was a hunting trophy,

which was not imported with a pre-CITES certificate. Table 6 shows the number

of rhino items exported from Australia between 2010 and 2015. Eleven items were

for personal use, and seven were commercial (total 18). Two commercial items

did not come with pre-CITES certification. No data was provided for the weight

of those items.[91]

Table 5: Imports of rhino horn (by number of items) into

Australia, 2010–2015:[92]

Table 6: Exports of rhino horn (by number of items) into

Australia, 2010–2015:[93]

Enforcement and detection of

elephant ivory and rhino horn at Australia's border

2.50

The enforcement of Australia's CITES obligations is the responsibility

of the DoEE and the Australian Border Force (ABF) and, if necessary, the

Australian Federal Police (AFP).[94]

The maximum penalty for a wildlife trade offence under the EPBC Act is 10

years imprisonment and a $210 000 fine for individuals and $1 050 000

fine for corporations. Wildlife items may be seized post-border if authorities

suspect an item has illegally entered Australia.[95]

17th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties

2.51

South Africa hosted the 17th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties

(CoP17) of the CITES between 24 September and 5 October 2016. During the two

week negotiations, 152 governments agreed to a resolution that:

...recommends that all Parties and non-Parties in whose

jurisdiction where there is a legal domestic market for ivory that is

contributing to poaching or illegal trade, take all necessary legislative,

regulatory and enforcement measures to close their domestic markets for

commercial trade in raw and worked ivory as a matter of priority.[96]

2.52

Under the resolution, CITES parties are required to report to the CITES

Secretariat the 'status of the legality of their domestic ivory markets', which

results in that information being reported to the CITES Standing Committee

meetings and at future CoPs.[97]

Although the resolution is not legally binding, it does elevate the issue, 'and

increase pressure on countries that have not closed their [domestic] markets'.[98]

2.53

This resolution led to a number of countries announcing and/or

implementing a ban on the domestic trade in elephant ivory. Recent

announcements include: the United States (June 2016);[99]

China (January 2018); Hong Kong (by 2021);[100]

Taiwan (by 2020);[101]

and the United Kingdom (UK).[102]

In late 2017, the European Union embarked on a consultation process about

restrictive measures against the ivory trade. The outcome of this consultation

is yet to be released.[103]

France has had a near-total ban for post-1947 ivory items since 2016, whilst

Canada banned the domestic ivory trade in 1992.[104]

2.54

Global support for the implementation of the CoP17 resolution was

further advanced in 2017, with the United Nations General Assembly resolution

(item 27) on Tackling illicit trafficking in wildlife, that called upon:

...Member States to ensure that legal domestic markets for

wildlife products are not used to mask the trade in illegal wildlife products,

and in this regard urges parties to implement the decision adopted at the 17th

meeting of the Conference of Parties to the Convention on International Trade

in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora recommending that all

Governments close legal domestic ivory markets, as a matter of urgency, if

these markets contribute to poaching or illegal trade.[105]

Australia's domestic trade regulations

2.55

The Commonwealth government does not regulate the domestic trade of

wildlife (including ivory and rhino horn); however, it is an offence under

section 303GN of the EPBC Act to be in possession of a wildlife specimen that

has been illegally imported into Australia.[106]

The internal movement of wildlife species is governed by the laws found within

each state and territory.[107]

There is no specific state and territory regulation of the domestic trade in

non-live elephant and rhino specimens.[108]

2.56

Further, there is no legal requirement for domestic sellers or

facilitators of ivory and rhino horn to provide evidence at the point of sale

(for example at an auction house) that demonstrates the item is a legal import,

or proves the provenance or age of a specimen. The DoEE may request an owner of

a wildlife specimen to produce evidence of its legal source.[109]

2.57

Despite the absence of domestic regulation, the DoEE stated that the

CITES Elephant Trade Information System's 2016 assessment of Australia's

domestic ivory market as 'small and/or well-regulated' and noted 'most seizures

of ivory in Australia is of small, worked items being traded as personal

effects'.[110]

The DoEE stated that the trading of these items within Australia is legal and

that it is 'legal elsewhere in the world';[111]

because the domestic trade is legal, no Commonwealth, state or territory agency

is responsible for, or required to monitor the elephant and rhino horn trade

within Australia.[112]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page