Budget Resources

David Watt, Nic Brangwin and Karen Elphick

Introduction

After the 2024 National

Defence Strategy (NDS) and revised Integrated

Investment Program (IIP) the Defence budget was predictable, but not

business-as-usual.

The 2023 Defence strategic review (DSR) recommended

far-reaching changes to the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) strategic

posture and capability in response to what it termed ‘radically different’

strategic circumstances (pp. 17 and 23). The DSR explained that intense China-US competition is the defining feature of

our region and our time, and Australia now faces the prospect of major

conflict directly threatening its national interest.

The 2024 NDS described further strategic deterioration and the

IIP identified necessary force structure changes (see below); parts of the

budget papers read quite differently as a result.

Large increases in defence funding,

but not yet

In 2024–25 Defence (including the Australian Signals Directorate

and the Australian Submarine Agency) will get $55.7 billion, which the Minister

for Defence’s Budget

media release states should rise to approximately $100 billion by 2033–34. The

resourcing section of the NDS stated that this funding line involved an

additional $5.7 billion across the forward estimates and $50.3 billion over the

decade to 2033–34. As Table 1 shows, despite a worsening strategic outlook, budget

planning has not changed much between the 2020 Defence strategic update

and the 2024 NDS.

Table 1 Defence funding

|

$b

|

2024–25

|

2025–26

|

2026–27

|

2027–28

|

|

Defence strategic update

|

55.5

|

58.1

|

61.2

|

64.6

|

|

NDS

|

55.5

|

58.4

|

61.2

|

67.9

|

|

Defence budget 2024–25

|

55.6

|

58.4

|

61.0

|

67.46

|

Sources:

Australian Government, Portfolio Budget Statements 2024–25: Budget

Related Paper No. 1.3A: Defence Portfolio, 2024, Table 4a, 16; Australian Government, National Defence Strategy, Department of Defence, 2024, 67;

Australian Government, 2020 Defence Strategic Update, Department of Defence, 2020, 54.

It is apparent from the table that the largest portion of

the $5.7 billion increase comes in the final year of the forward estimates.

This has troubled some commentators because Defence’s buying power does not

increase much until 2027–28 and it has to some extent been undermined by the

inflation spikes of the past few years (for which the Defence Budget has not

been adjusted). As Strategic Analysis Australia’s Marcus

Hellyer has written:

It’s an increase of $2,356 million (4.4%) in nominal terms

over the 2023-24 budget, but only $889 million (1.6%) in real terms. That means

this year Defence is only just keeping its nose ahead of inflation.

Hellyer goes on to say:

Many commentators have noted the vast bulk of this funding

sat outside the forward estimates in the last six years of the decade. From the

PBS we can see that it’s even worse than that: $3.8 billion of the $5.7 billion

sits in 2027-28, the final year of the forward estimates – at least one and

maybe two elections away. That means there’s only $1.9 billion of new money in

the next three years. It’s one of the glaring discrepancies between the

Government’s stated assessment of the need for urgency in light of our rapidly

declining strategic environment and its funding model—it’s only increasing the

funding line it inherited from the previous government by around 1% over the

next three years.

Are the submarines distorting the

defence budget?

Another issue attracting comment has been the dominance of

the AUKUS nuclear-powered submarines and the general-purpose frigate program in

the $50 billion of increased funding across the decade. Marcus Hellyer breaks

down the $50 billion as follows:

-

$38.2 billion of the released contingency reserve (the initial

$30.5 billion plus the first year of the on-going $7.7 billion—this covers the

SSN funding gap

-

$11.1 billion previously announced by the Government to cover the

general purpose frigates

-

the $1 billion listed above to accelerate delivery.

The question will be whether the $1 billion noted above plus

the as-yet-unknown funding being found as a result of the reprioritised IIP

will be sufficient to meet the ADF’s other needs.

Where are the savings?

Substantial new spending in some acquisition projects is

revealed in the 2024–25

portfolio budget statement (PBS), including $2,591 million for the nuclear

submarine project (DEF 1). However, the overall expenditure for approved military

equipment acquisition projects has increased by only $679 million for 2024–25,

and overall new spending for Defence is just $400 million. There must, therefore,

be nearly $2 billion in reductions, but they are hard to find.

Much of the spending in this Budget appears to have been

achieved by ‘reprioritisation’. That is, the government has juggled project

schedules, bringing some capability acquisition forward while slowing or

reducing spending on other projects. The Defence Minister previously identified

‘an

initial $7.8 billion reprioritisation’; however, the government has not

provided a list of the affected projects.

Future defence annual spending is planned over a 10 to 20-year

timeframe. Money is notionally allocated to various projects and schedules

adjusted to smooth Defence spending. Adding a large project, like the nuclear

submarines or the general-purpose frigates, means other planned, but not yet

funded, projects must be cancelled or delayed to avoid a big jump in annual

spending. Several acquisition programs which appeared in the 2020 Force

Structure Plan or had been announced, are now absent from the IIP. Chief

among those is the cancelled Attack class submarine program. Other reductions

include:

-

the delay or cancellation of programs to acquire:

- a

fourth squadron of F-35 JSF combat aircraft

- a

second regiment of AS9 Huntsmen self-propelled howitzers (LAND 8116)

- medium-range

missile defence systems (AIR 6502)

- 2

sea lift and replenishment ships.

-

reducing the planned 450 Redback infantry fighting vehicles to

129 (LAND 400 Phase 3)

-

early retirement of 2 Anzac class frigates, which reduces planned

sustainment and upgrade costs

-

a more limited Anzac class frigate upgrade.

Strategy of denial – prioritising long-range

strike and ADF resilience

The NDS states that a strategy of denial will become the

‘cornerstone’ of defence planning (p. 7). To counter emerging threats, the ADF

must be able to deny

an adversary freedom of action by demonstrating the capability and resolve

to respond to attacks on Australian territory and further offshore along critical

sea lines of communication (NDS, pp. 21–25). Necessary changes identified by

the IIP include:

-

increasing long-range strike capability and littoral

manoeuvrability

-

improving ADF operating resilience through increased

interoperability with allies, deepening munitions stockpiles and hardening

northern bases to survive attack

-

accelerating local production of munitions, guided weapons and

other systems to reduce vulnerability in long supply chains for Australia and

allies.

The key long-range strike capability, and the one that

dominates the Defence budget, is the nuclear-powered submarine program.

Nuclear-powered submarine program

Australia’s acquisition of nuclear-powered, conventionally

armed submarines is a key part of the AUKUS

Partnership announced on 16

September 2021. On 14

March 2023 the pathway for this acquisition was revealed. The

main elements involve:

-

developing Australia’s industrial capacity to support

nuclear-powered submarines (NPS) through increased UK and US submarine visits

to HMAS Stirling, WA. This will evolve into the Submarine

Rotational Force – West from 2027

-

acquiring at least 3 (potentially 5) Virginia

class submarines from the US in the early 2030s

-

constructing a new class of submarine, SSN-AUKUS,

with the UK constructing the first of class in the late 2030s and Australia

building its first, in Australia, in the early 2040s.

The Defence

Minister stated that the cost of the NPS program would roughly amount to

0.15% of GDP for the life of the program, which Prime

Minister Albanese estimated could be ‘between $268 billion and $368 billion’.

Last year, the

Parliamentary Budget Office estimated the amount to be $367.6 billion in

out-turned dollars, which included a $122.9 billion contingency.

The 2024

IIP provided $53 to $63 billion of planned investment from 2024–25 to

2033–34, of which $13 billion was approved and $40 to $50 billion

unapproved (IIP, pp. 15, 24 and 29).

Given this undertaking, it is unsurprising the NPS program

is the most prominent feature of the 2024–25

Defence budget and will be for decades to come.

The newly established Australian

Submarine Agency (ASA) is a new line item in the ‘Funding from Government’

table in the 2024–25 PBS (Table 4a, p. 16) and a new section is dedicated to

the ASA near the end of the PBS (pp. 183–202). ASA’s actual estimated funding

for the current financial year is $243.4 million, with regular annual

increases peaking at $527.4 million in 2026–27, then reducing to $378.1 million

in 2027–28. Funding over the forward estimates totals $1,719 million (p. 16).

The NPS program is funded in the 2024–25

Defence Budget under the IIP, with its budget and expenditure shown in

Defence Program 2.16 (2024–25 PBS, p. 184). This is separate

from ASA funding, although ASA is responsible for the expenditure of

Program 2.16. The 2024–25

Defence Budget allocates more than $11.8 billion over the forward estimates

to Program 2.16 (this figure excludes the estimated actual figure of $475.2

million for 2023–24) (2024–25 PBS, p. 92).

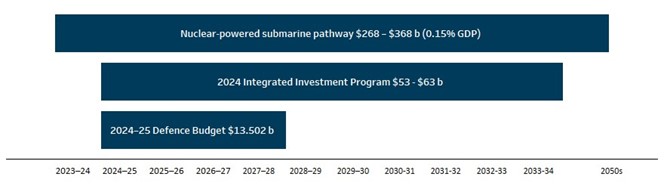

Figure 1 below illustrates the long-term funding statements

in line with current budget allocations. The 2024–25 Defence Budget figure is a

consolidated ASA and Program 2.16 figure.

Figure 1 NPS program expenditure over the life of the program

Source: Richard Marles (Deputy

Prime Minister and Minister for Defence), ‘AUKUS’,

transcript, 14 March 2023; Anthony Albanese, Questions Without Notice: AUKUS, House of Representatives, Debates, 27 March

2023; Australian Government, Portfolio Budget Statements 2024–25: Budget Related

Paper No. 1.4A: Defence Portfolio, 16; 92.

For the first time, the NPS program is listed in the Top 30

military equipment acquisition program table and identified as DEF 1 (PBS,

Table 54, p. 127). It shows an approved total project expenditure of $13.6 billion

over the forward estimates (this figure includes acquisition costs totalling

$11.8 billion and other project inputs totalling $1.8 billion), which shows

around $2.6 billion is to be expended in 2024–25.

Where these funds are being directed is not clear. The

project description notes the ‘project includes a fair and proportionate

contribution to our AUKUS partners’ submarine industrial bases …’ (p. 127).

ASA’s February

2024 Additional Estimates briefing notes state the proportion of investment

towards the US submarine industrial base is estimated at US$3 billion. The 22 March 2024 announcement on the

Australia-UK Submarine Strategic Partnership stated Australia would contribute £2.4 billion over 10 years to ‘expand the Rolls-Royce facility in Derby in the UK’. While media reports converted these amounts to Australian dollars

(an estimated A$4.7 billion for the US and A$4.6 billion for the UK), the actual

costs at the time of transfer will be subject to currency fluctuations.

Additionally, there are 2 major infrastructure projects

related to DEF 1:

The 2024–25

Defence budget also includes NPS sustainment costs (p. 17). While the

figures are relatively low, totalling $322.8 million from 2023–24 to 2027–28,

this product (along with Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordinance sustainment)

has been reclassified from Other Minor Sustainment to separate line items in

the PBS.

Reprioritisation – notable funding

changes in military equipment acquisition and sustainment

Library analysis suggests that many of the Top 30 acquisition

and sustainment projects underspent in 2023–24 have also had spending reduced for

2024–25. However, any changes among the hundreds of projects that do not appear

in the Top 30 tables are not visible in the Budget.

The tables below show notable increases and reductions in Top

30 programs. Where an increase appears due to a program underspend being

carried forward, no change to spending is noted. If the full underspend is not

brought forward, it is treated as a reduction.

It is important to be aware that variations in annual

spending are normal; expenditure is not even across each year of a big

acquisition project. Annual spending is typically low during the design phase,

rises to a peak through acquisition (which is longer for long-term build

projects) and slowly declines through the sustainment phase. It is only

possible to know with certainty that a particular project has been decelerated

or accelerated by comparing tables of planned annual spending – which are not

visible in the Budget.

Air domain

Table 2 identifies air domain spending that has increased

and Table 3 outlines reductions in spending. The IIP requires that the Royal Australian

Air Force deepen stocks of air-launched

missiles. While AIR 6004, the project to acquire the JASSM

ER missile, appears to have been substantially boosted, the increase is

largely due to its merging with AIR 3023, the project to acquire Long-Range Anti-Ship

Missiles. While there is still a significant boost in overall approved

expenditure, annual spending for the 2 projects combined has slowed.

Spending for the EA-18G Growler (AIR 5349) at first glance also

seems to have jumped, but again it appears that the previously separately

funded Phase 3 (airborne electronic attack capability upgrade) and Phase

6 (next generation of major EA-18G upgrades) have been integrated and annual

spending has slowed. By contrast, both the P-8A Poseidon maritime surveillance aircraft

acquisition and capability upgrade and sustainment programs have been given increased

funding. Hardening of northern bases is an area prioritised by the IIP, however,

airfield capital works for Curtin, Tindal and Townsville had a significant

underspend last year and reduced funding this year.

Table 2 Air domain new and increased spending

($m)

| Project |

Approved expenditure at 2023–24

PAES |

Approved expenditure 2024–25 |

Revised budget estimate at 2023–24

PAES |

Estimated expenditure 2023–24

(a) |

Budget estimate 2024–25 |

Air-launched multi domain strike

(AIR 6004)

now includes AIR 3023 |

576 |

2,508 |

180 |

486 |

412 |

P-8A Poseidon

(AIR 7000) |

6,624 |

8,448 |

145 |

352 |

274 |

| P-8A Poseidon sustainment (CAF35) |

- |

- |

187 |

- |

247 |

| MC-55A Long-Range ISREW Aircraft

sustainment (CAF40) |

- |

- |

88 |

- |

130 |

(a) Calculated

by subtracting Cumulative

Expenditure to 30 June 2023 in Table 64 of 2023–24 portfolio additional estimates

statements (PAES) from Estimated Cumulative Expenditure to 30 June 2024 in Table 54 of the

2024–25 PBS.

Source:

Parliamentary Library calculations

Table 3 Air domain spending reduced ($m)

| Project |

Approved expenditure at 2023–24

PAES |

Approved expenditure 2024–25 |

Revised budget estimate at 2023–24

PAES |

Estimated expenditure 2023–24

(a) |

Budget estimate 2024–25 |

MQ-28A Ghost Bat (AIR 6014)

previously DEF 6014 Phase 1 |

858.0 |

858.0 |

364.0 |

283.0 |

212.0 |

EA-18G – Growler

(AIR 5349)

AIR 5349 Phase 6 and Phase 3 integrated |

7,564.0 |

7,563.0 |

378.0 |

402.0 |

302.0 |

| Airfield capital works P0006

(Curtin, Tindal and Townsville) |

95.3 |

95.3 |

12.4 |

2.0 |

9.4 |

| Short-Range Ground Based Air Defence (LAND 19) |

1,529.0 |

1,527.0 |

311.0 |

312.0 |

201.0 |

(a) See

note at Table 1.

Source:

Parliamentary Library calculations

Land domain

Army is required to restructure 3 combat brigades to

emphasise amphibious capability, with a new dedicated fires brigade and

littoral manoeuvre group. If required, these brigades can deploy forward to positions

along Australia’s sea lanes and provide long-range strike against adversary ships

and aircraft. Spending increases listed in Table 4 show the beginning of

prioritisation of new littoral manoeuvre capabilities. Accelerated projects include

the acquisition of HIMARS

long-range rocket artillery and the Redback infantry fighting vehicle. Delivery

of Army’s planned 18 landing craft medium and 8 landing

craft heavy (LAND 8710 Phases 1-2) has also been brought forward 7 years, but the

planned cost of

$7–10 billion over the decade does not yet appear in the Budget. Table 5

demonstrates some of the reductions in other land domain projects.

Table 4 Land domain new and increased spending

($m)

| Project |

Approved expenditure at 2023–24

PAES |

Approved expenditure 2024–25 |

Revised budget estimate at 2023–24

PAES |

Estimated expenditure 2023–24

(a) |

Budget estimate 2024–25 |

| UH-60M Black Hawk Utility Helicopter (LAND 4507) |

3,872 |

3,871 |

396 |

365 |

645 |

Redback Infantry Fighting Vehicle

(LAND 400 Phase 3) |

- |

7,246 |

- |

318 (b) |

626 |

| Explosive Ordnance – Army

Munitions Branch sustainment (CA59) |

- |

- |

242 |

- |

395 |

AH-64E Apache Attack Helicopter

(LAND 4503) |

5,146 |

5,144 |

126 |

170 |

284 |

First Long-Range Fires Regiment

(LAND 8113 Phase 1) |

- |

2,337 |

- |

104 (b) |

199 |

Individual Combat Equipment

(LAND 300)

includes LAND 159 |

538 |

1412 |

154 |

876 |

145 |

(a) See note at Table 1.

(b) New

project in 2023–24 so there was no cumulative spending to 30 June 2023.

Source:

Parliamentary Library calculations

Table 5 Land domain spending reduced ($m)

|

Project

|

Approved expenditure at 2023–24

PAES

|

Approved expenditure 2024–25

|

Revised budget estimate at 2023–24

PAES

|

Estimated expenditure 2023–24

(a)

|

Budget estimate 2024–25

|

|

Boxer Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles

(LAND 400 Phase 2)

|

5,918

|

5,903

|

625

|

504

|

656

|

|

Armoured Combat

(LAND 907)

|

2,395

|

2,428

|

634

|

591

|

624

|

|

AS9 Huntsmen Self-Propelled

Howitzers (LAND 8116)

|

1376

|

1371

|

262

|

253

|

246

|

(a) See

note at Table 1.

Source:

Parliamentary Library calculations

Maritime domain

Table 6 shows the scale of new and accelerated spending in

the maritime domain. The most important of the Collins class life of type

extension programs (SEA 1450) appears to have accelerated, and initial annual funding

of $2,591 million for the future nuclear-powered submarine program is now

visible. Naval long-range strike weapons are another priority area and Hobart

class destroyers will be upgraded to an Aegis baseline 9 combat system to allow

better targeting and the addition of longer range strike missiles. Additional

Seahawk helicopters, which have a role in submarine detection, are also being

acquired. Projects to acquire new capabilities in maritime mining and maritime

electromagnetic manoeuvre warfare (electronic warfare) appear in the Top 30

for the first time. The IIP planned spend of

$7–10 billion over the decade for the first batch of general purpose

frigates also does not yet appear in the Top 30 table.

Table 7 shows some reduced spending. Despite the need for

deeper stocks of strike weapons, the SEA 1300 guided weapons budget has

reduced by 7.2% this year. The medium-term reduction in the number of surface

combatants (including early retirement of 2 Anzac class frigates) will likely move

demand for additional missiles towards the end of the 10-year plan.

The Hunter class frigate also appears to have a reduced

spend this year. However, only spending for the Phase 1 design and

construction budget appears in the Budget. The main construction phase is

planned to begin early in 2024–25. That is likely to result in an increase of

approved expenditure of around $20 billion for construction of the first 3

ships. The annual increase in spending will depend on the build schedule.

Table 6 Maritime domain new and increased

spending ($m)

| Project |

Approved expenditure at 2023–24

PAES |

Approved expenditure 2024–25 |

Revised budget estimate at 2023–24

PAES |

Estimated expenditure 2023–24

(a) |

Budget estimate 2024–25 |

Nuclear-powered submarines

(DEF 1) |

- |

13,588 |

- |

456 (b) |

2,591 |

Collins Life of Type Extension

(SEA 1450) previously sustainment CN62 |

- |

1045 |

160 |

318 |

240 |

Aegis Baseline

(SEA 4000 Phase 6) |

2,360 |

2,477 |

506 |

|

582 |

MH-60R Seahawk Helicopter

(SEA 9100) |

- |

5,149 |

- |

- |

523 |

Maritime Electromagnetic

Manoeuvre Warfare

(SEA 5011) |

- |

726 |

- |

- |

141 |

Maritime Mining

(SEA 2000) |

- |

932 |

- |

- |

136 |

(a) See

note at Table 1.

(b)

New project in 2023–24 so there was no cumulative spending to 30 June 2023.

Source:

Parliamentary Library calculations

Table 7 Maritime domain

underspending and reduced spending ($m)

| Project |

Approved expenditure at 2023–24

PAES |

Approved expenditure 2024–25 |

Revised budget estimate at 2023–24

PAES |

Estimated expenditure 2023–24

(a) |

Budget estimate 2024–25 |

Maritime Guided Weapons and Munitions

(SEA 1300) |

8,953 |

8,937 |

763 |

733 |

708 |

Hunter Class Frigate

(SEA 5000) |

7,263 |

7,254 |

1,250 |

1,203 |

813 |

(a) See

note at Table 1.

Source:

Parliamentary Library calculations

Space and cyber domain and joint

capability

Table 8 shows spending has increases on some priority

logistic and enabling projects. Command, control, communication and targeting will

be hardened against disruption and sped up by improving interoperability

between the 3 services and Australia’s allies. There is also a new project to

improve fuel security.

Local explosive ordnance manufacturing capacity will be

increased. Spending to support that expanded capacity has been increased by 45%

since the 2023–24 Budget when it was $100 million.

Table 9 shows that a program which would be expected to be a

priority after the IIP – to increase and harden guided weapons and explosive

ordnance (GWEO) storage – commenced after the last Budget and was first

captured in the 2023–24 PAES, but there was, a large underspend in 2023–24 and

a significantly reduced estimate for 2024–25.

Table 8 Joint capability new and increased

spending ($m)

| Project |

Approved expenditure at 2023–24

PAES |

Approved expenditure 2024–25 |

Revised budget estimate at 2023–24

PAES |

Estimated expenditure 2023–24

(a) |

Budget estimate 2024–25 |

Integrated Air and Missile Defence Command and

Control

(AIR 6500) |

- |

1,209.0 |

- |

389.0 |

238.0 |

| Explosive Ordnance Manufacturing

Facilities (CJC01) |

- |

- |

134.0 |

- |

145.0 |

| Defence Fuel Transformation

Program – Tranche 2 Facilities Project |

- |

286.9 |

- |

9.7 |

82.0 |

| Facilities to Support JP 8190

Phase 1 Deployable Bulk Fuel Distribution |

15.0 |

15.0 |

2.6 |

0.1 |

10.6 |

(a) See

note at Table 1.

Source:

Parliamentary Library calculations

Table 9 Joint capability

reduced spending ($m)

| Project |

Approved expenditure at 2023–24

PAES |

Approved expenditure 2024–25 |

Revised budget estimate at 2023–24

PAES |

Estimated expenditure 2023–24

(a) |

Budget estimate 2024–25 |

| GWEO storage (c) |

161.9 |

161.9 |

72.4 |

43.1 |

45.6 |

(a) See

note at Table 1.

(c) Cumulative figures from 3 projects in Table 66 in the 2023–24 PAES and Table 56 in the PBS.

Source:

Parliamentary Library calculations

All online articles accessed May 2024

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.