Chapter 4

Food security—agriculture and fisheries

4.1

In Pacific island countries most people live and work in rural areas and

depend heavily on produce from the land and sea for their livelihood.[1]

Thus, agriculture, fisheries and forestry form the basis of the economies of

the Pacific island countries and are likely to continue to do so for the

foreseeable future.[2]

Allowing for variation between the countries, approximately 80 per cent of

employment is generated by these three key activities.[3]

The committee starts its analysis of how Pacific island countries are meeting

their economic challenges with a general discussion on food security and

sustainable development. In this chapter, the committee focuses on agriculture and

fisheries as key economic sectors.

Food security

4.2

Although subsistence production dominates the economic life of people in

Pacific island countries, they have become 'increasingly reliant on imported

staples such as rice, flour and noodles'.[4]

The rise of food prices during 2008 heightened concerns about food security in the

region. In this regard, a paper prepared by the Secretariat of the Pacific

Community (SPC) observed that generally Pacific island countries and

territories had managed to achieve food availability except during major

natural disasters. It noted, however, that the situation was changing, with

several island countries becoming net importers of food. The Secretariat

attributed this trend in part 'to the stagnation of agricultural productivity

and coastal fisheries production as a result of declining investment of these

sectors'.[5]

In its assessment, agricultural productivity and coastal fisheries production

were not keeping pace with rapid population growth.[6] Based on a study of nine Pacific island

countries, the Secretariat found:

...if the value of food imports grows in line with expected

population growth, these countries will collectively be spending an additional

US$120 million on food imports by 2030. Financing such expenditure will, for

example, require a 79% increase in agriculture, forestry and fisheries export

earnings in Vanuatu, and a 10% increase in remittances in Samoa.[7]

4.3

At the 2008 UN-sponsored World Food Summit, the Secretariat highlighted

the need for Pacific island governments and donors 'to reverse the declining

investment in the agricultural sector and recognise the role it plays in

safeguarding food security in the face of volatile global food prices'. It noted,

however, that the current crisis also presents the region with an opportunity:

Many Pacific Islands are blessed with a rich diversity of

traditional staples such as taro, cassava, sweet potatoes, breadfruit and yams

which are not as important in global trade as some of the imported commodities

on which we’ve come to rely. Increased production of these local foods could

help to limit the impact of rising prices.[8]

4.4

According to AusAID's 2009 Pacific economic survey, however, agricultural productivity in Pacific

island countries has 'stagnated for the last 45 years'.[9]

It should be noted that, at the moment, while poor nutrition and malnutrition

are problems in some Pacific island countries, starvation is not. For example,

AusAID informed the committee that there are some very poor communities in PNG where child malnutrition occurs but that protein malnutrition was not such a concern for

Pacific islands communities with ready access to fish.[10]

The Prime Minister of PNG also noted that no-one is starving in the traditional

villages of PNG where people help each other. He noted though that there might

be one or two in Port Moresby—'kids who come to look for opportunities for

education and health, when they miss out, then they of course roam the

streets'.[11]

4.5

Some island countries are responding to the threat of food insecurity in

the region 'by calling on people to grow more local foods'.[12]

The Government of Tonga has stated that, given its natural resources, its main

challenge is to be 'more self-reliant and self-sufficient'. It is looking to

boost agricultural production and 'has prioritized the development of the

agricultural sector to maintain adequate rural living standards, provide food

security, generate export earnings, and reduce dependence on food imports'.[13]

President Manny Mori of the Federated States of Micronesia was quoted at the

2008 World Food Summit:

...for too long our children have been fed on rice as staple

food because of the convenience of preparation and storage. We have neglected

our responsibility and even contributed to their lower health standards by

failing to teach them to appreciate the natural food and bounty of our islands.[14]

4.6

He noted that Fiji had 'just launched a "Plant Five a Day"

campaign in an effort to encourage more people to plant in their gardens'.[15]

Other Pacific island countries are also introducing various incentives to

encourage greater local production. Nauru has included agriculture in its

school curriculum to promote farming and food production skills among the

younger people, and Vanuatu has an agricultural school, partly funded with

donor assistance, aimed to attract school leavers to farming.

Sustainable development

4.7

At a time when Pacific Islanders are being encouraged to increase their

agricultural productivity, concerns are mounting about sustainable development.

This issue cuts across all sectors involving land and water use.

4.8

For many years, a considerable number of studies, conferences and

workshops have pointed to a range of environmental, demographic,

socio-cultural, and land practices that are putting additional strain on the

already existing vulnerability of these island states and the rich biodiversity

of the region.[16]

They have noted that the fragile terrestrial, coastal and marine environments

upon which most island people rely were increasingly under threat from

unsustainable harvesting and land use practices, increasing populations,

resource exploitation, pollution and climate change.[17]

4.9

CSIRO informed the committee that over exploitation of natural

resources, such as fishing, groundwater and forestry, was undermining the

economic viability of many Pacific island countries to operate as nation

states.[18]

It stated that in PNG:

At the local level, environmental degradation and

biodiversity loss have the largest impact on the poorest members of the

community who may rely on these natural assets for subsistence harvesting

(food, firewood), storm protection, etc.[19]

4.10

These risks to a long-term sustainable and productive agricultural sector

require Pacific island countries to rethink and adapt to the challenges that

have emerged over recent years. Thus, research and development is critical to

finding solutions to the problems created by rising food prices, growing

populations, land use practices and changes to climate. For example, at the 2008

meeting of the Heads of Agriculture and Forestry Services, Fiji reported that strengthening breadfruit production depended on 'increased access and

availability to more varieties to enable year-round supply'. Also at this

meeting, Kiribati noted the importance of adaptation measures, including the

need for climate resilient planting materials and livestock breeds; Niue

highlighted the need to 'lift conservation and management efforts'; and Tuvalu noted

the promotion of crop varieties more tolerant to salt and drought.[20]

Several Pacific island countries mentioned the need for improved education

facilities at both school and tertiary level. For example, Niue stated that

there was an urgent need for training under the Paravet programme'.[21]

Fiji argued that agricultural sciences 'should be incorporated into school

curricula at the primary and secondary level'.[22]

Some countries also suggested that technical assistance was required to help

the community 'accept and adjust to the need for more local food production'.[23]

Research and development for

increased productivity and food security

4.11

A number of countries at this 2008 meeting noted that efforts should be

made to develop better ways of getting information to farmers. PNG stated that 'improved extension, education and awareness programmes to promote local food

production were essential'.[24]

Fiji's Minister for Primary Industry and Sugar told graduates from the Fiji

College of Agriculture that:

In order to ensure that the benefits of these technologies

are felt across the farming communities, efforts must be made to increase the familiarity

with these technologies that even the smallest farms can use them. Agricultural

training has potential to improve traditional agriculture methods as well.[25]

4.12

The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR)

also recognised that research is urgently needed into more effective ways to achieve

a broader adoption of the results of research and development (R&D). Dr Simon

Hearn, ACIAR, argued that the challenge was to get better technology to

smallholders where there is 'tremendous latent potential to increase yields'.

He was of the view, however, that extension services in some of the countries

'have become rather the second cousins of the system'.[26]

For example, few of the participants in the 2008 Solomon Islands people's

survey reported visits by agricultural extension officers.[27]

Cook Islands, Niue and Kiribati have publicly acknowledged the value of the

community-based approach used by the SPC's Development of Sustainable

Agriculture in the Pacific.[28]

Kiribati noted that one of its strengths was 'the direct involvement of

farmers, women and youth'.[29]

Committee view

4.13

Clearly, while research and education in sustainable development is a

high priority for Pacific island countries, this alone is not sufficient to

boost the agricultural production in the region. The knowledge and know-how

gained in the classroom or laboratory must be conveyed to, and adopted by,

farmers on the ground. The linkages between research, education and extension

are vital to ensuring that Pacific island countries build the capacity in

individuals and communities to better care for their land, manage sustainable

production and increase their productivity. Any research project designed to

assist Pacific island countries improve their agricultural productivity and

sustainable development should contain a clear path from research and

development to producers working smaller farms.

Fisheries

4.14

Evidence presented to the committee also highlighted the central

importance of the fishing industry to food security in the Pacific and of

threats to its sustainability. Because of their location and small land mass, Pacific

island countries are effectively coastal entities. With their population and

economic activities concentrated in the coastal zone, Pacific island countries

depend largely on coastal and marine resources for sustainable development. A

study by the Secretariat of the Pacific Community found that fish accounts for

70–90 per cent of total animal protein intake in Pacific island countries. Most

of this fish comes from subsistence fishing. It noted further that the use of

fish for food security is critical because the 'total population of the Pacific

will increase by almost 50% by 2030'. The study concluded:

The challenge for national planners is to ensure that growing

populations continue to have physical, social and economic access to the fish

they need. In rural areas, access to fish needs to be made available in ways

that enable households to catch or produce it for themselves. In urban centres,

it needs to be supplied at affordable prices.[30]

4.15

For many years, however, international bodies have recognised the

difficulties facing Pacific island countries in managing their fisheries sector

and in achieving ecologically and economically sustainable use of coastal and

marine resources.

Coastal fisheries

4.16

Pacific island countries gain significant economic and nutritional

benefit from subsistence coastal fishery resources. According to estimates,

over 80 per cent of all coastal catch is consumed in the subsistence sector,

particularly in rural areas, of some Pacific small island developing states.[31]

But the health of these marine habitats is at risk from pollution,

over-exploitation, conflicts between competing resource users and the effects

of natural hazards and extreme weather events.[32]

Recently, the UN's Commission on Sustainable Development noted that exports of

marine products from coastal areas had increased and that:

The sustainable management of fisheries has thus become

increasingly urgent, as the demand for both subsistence and commercial fishery

products have raised the incidence of overfishing.[33]

4.17

DFAT raised similar concerns about the heavy dependence on coastal

fishing resources for subsistence food and the diminishing stocks in many areas

due to human population growth and unsustainable fishing practices. It also

highlighted the increasing importance of the sustainable management of

traditional fisheries resources 'given the global rise in food prices and

increased cost of imported non-traditional foods'.[34]

A 2007 ACIAR project recognised that 'managing the pressures on coastal reef

fisheries was a challenge for local communities, who have relatively few tools

and traditions to reconcile the limited resources with the increasing demand

for them'.[35]

Mr Barney Smith, ACIAR, said that despite the importance of these fisheries, 'the

governance services in terms of understanding and managing fisheries on coastal

inshore resources is relatively weak'.[36]

4.18

With regard to aquaculture, ACIAR was of the view that the Pacific

island countries with their large, clean and sheltered areas of seawater and

high biodiversity were 'ideally suited to a range of aquaculture activities'.

It stated, however, that aquaculture in the Pacific had been 'dogged by low

production levels and few success stories'.[37]

4.19

Although critical to the informal economy of many Pacific island

countries, coastal fishing did not figure prominently in evidence presented to

the committee. Most of the evidence centred on large-scale commercial fishing.

The committee is of the view, however, that the attention given to ocean

fishing should not overshadow the importance of the smaller commercial and

subsistence fishing activities in the coastal areas of the region. Pacific

island countries would benefit from assistance in both research and development

and in raising awareness of how better to manage these resources.

Commercial fisheries

4.20

Ocean fishing is also an important food source for Pacific island

countries. But the opportunities to meet the food security needs for many Pacific

island countries depends on the long-term sustainable management of ocean fisheries

resources in the region.[38]

DAFF underscored this point. It stated that 'Support for the sustainable

development of fisheries resources and preventing the overfishing of stocks in

the western and central Pacific Ocean is crucial for the viability of Pacific

island countries as sovereign states'.[39]

A number of international organisations, however, have expressed concern about

the failure to protect marine stocks to sustainable levels and the poor management

of fisheries which threaten the viability of the industry.[40]

ACIAR noted that 'ineffective policy implementation is seen as a significant

impediment to development and progress'.[41]

Over exploitation

4.21

DFAT informed the committee of evidence indicating that 'serious

over-fishing of the two major commercial tuna stocks (bigeye and yellowfin) may

place these at a serious risk of collapse within 3–5 years if corrective action

is not taken'.[42]

Mr John Kalish, DAFF, emphasised the seriousness of this assessment:

Essentially, if the rate of overfishing continues at this

current rate then the stock will move to a state where it may actually move

into a declining phase.[43]

Such assessments are based on a solid body of research.[44]

4.22

The migratory nature of the fish stocks, the immense area covered by fishing

activity, the number of countries engaged in the industry and the growing

demand for fish from the region complicate the management of Pacific fish

stocks.

Distant Water Fishing Nations

4.23

Despite mounting concerns about the over exploitation of some species of

fish in the region, the number of distant water fishing nations (DWFNs)

operating in the Southwest Pacific is increasing. Mr Kalish reported that in

recent years, new players had entered the industry and members of the European Community

had increased their activity in the area. He explained that in the past their

predominant fishing grounds had been the Atlantic and the Indian oceans, but

that their attention was shifting to the Pacific.[45]

According to Mr Kalish, record catches were reached in 2008—2.4 million tonnes—which

was about 200,000 tonnes over the catch in the previous year.[46]

Furthermore, the demand for fish from the region was rising. Mr Kalish noted

that 'given the increased competition for fish, particularly high valued fish

such as tunas used for sashimi, there is a shortage of supply'. He explained:

Countries like China, which are becoming more affluent, have

greater demand for this product, and as a result the north Asian countries, in

particular, are not interested in seeing their access to this product reduced...[47]

4.24

Mr Kalish also informed the committee that there are countries interested

in tuna for canning, with the region providing about 60 per cent of the world's

supply.

4.25

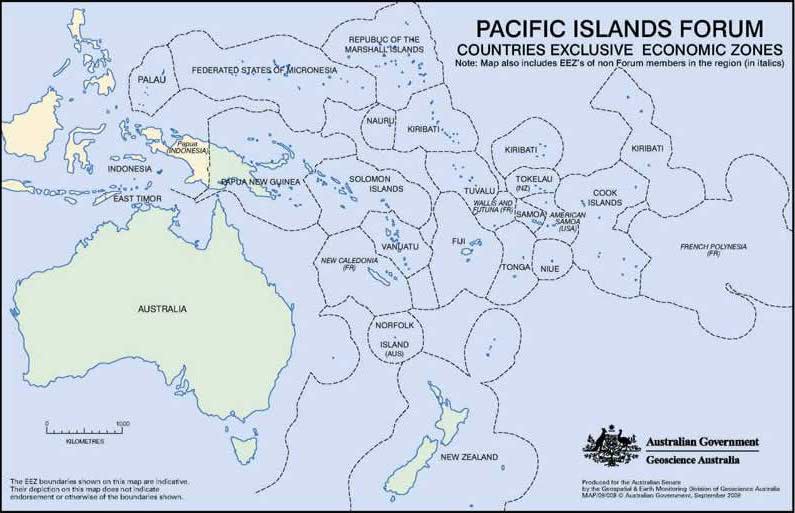

The activities of DWFNs in the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of the Pacific

island countries are regulated by the relevant sovereign state and the Forum

Fisheries Agency (FFA).[48]

They must be licensed to fish within those waters and be registered with the FFA. DWFNs must also observe certain monitoring, control and surveillance measures that allow the

FFA and the member countries to keep track of their activities, for example,

through vessel monitoring systems.

4.26

Mr Kalish drew attention to the tension between the aspirations of the Pacific

island countries, which need to be protected, and those of countries seeking

access to fish in the region.[49]

He informed the committee that there had been 'very heated debate and

intercessional workshops that have sought to identify compromise positions that

would be amenable to the different sectors that fish in the western South

Pacific'.[50]

Illegal activities

4.27

Pacific island countries are scattered over a large geographic area and

encompass a vast maritime EEZ. Thus, the fishing industry in particular

presents enormous difficulties for Pacific island countries struggling to

monitor unauthorised activities in their broad expanses of water. An OECD Policy

Brief noted that in spite of efforts to combat illegal, unreported and

unregulated fishing, such activities remain widespread.[51]

In its submission, DFAT contended that the landed value of fish taken from the

region is vastly under-reported, with poaching estimated at 40 per cent.[52]

Mr Kalish said:

The exact magnitude of the problem would be difficult to

quantify. One of the problems that we have is determining whether a vessel is

reporting accurately as to whether its fishing activity is taking place in an exclusive

economic zone or on the high seas...to a large extent many of the problems are

due to inadequate management of the current catch levels.[53]

4.28

For example, he explained that there were instances where vessels that

have not applied for access, 'have gone into exclusive economic zones and

vessels that have access have extended their stay'.[54]

The requirement to monitor and police their EEZ is a key economic challenge for

Pacific island countries. Brigadier Andrew Nikolić, Department of Defence,

informed the committee that Pacific island countries:

...lack the capacity to effectively protect their EEZ resources

from illegal fishing and to monitor their maritime boundaries against threats

like smuggling without substantial help from outside.[55]

4.29

DFAT also referred to the difficulties Pacific island countries face in

policing and prosecuting the illegal and under-reported fishing occurring in

their EEZs.[56]

Conservation and management

4.30

A major concern for countries in the region is that fishing activities

carried out in breach of agreed arrangements may undermine the sustainability

of the industry in the Pacific. Because of the migratory nature of fish and the

large areas they traverse, Pacific island countries recognise the value in

collaborating to protect their interests effectively. Two major regional

organisations figure prominently in overseeing fishing activities in the

region. The FFA and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission

(WCPFC) work cooperatively to ensure sustainable fishing in the region. FFA members make up 17 (including Australia and New Zealand) of the 32 participating members

and territories in the WCPFC.

4.31

Mr Smith, ACIAR, explained that the WCPFC is a body that can 'begin to

address some of the more difficult issues, such as overfishing, by keeping a

cap on the total catch and, more importantly, keeping the effort at a level

that the stocks can sustain'.[57]

Mr Kalish explained that although there had been some breaches of the cap, the

problem was with the cap itself. The agreed limit was established when the

fishing capacity and the fishing effort was already too high, so the cap is

near the maximum take that has occurred for bigeye tuna.[58]

Thus, although the limits imposed on the size of the catch are generally observed,

some fish stocks continue to decline. According to Mr Kalish:

As a body made up of member states it is contingent upon the

member states [of WCPFC] to agree to take action to conserve the stocks. Based

on the recommendation of the scientific community, over the past three years

they have recommended a 25 per cent reduction in fishing mortality for bigeye.

This year the scientific committee met in August [2008] and recommended a 30

per cent reduction in fishing mortality.[59]

4.32

Until recently, Pacific island countries as members of the FFA were critical of the lack of progress in achieving concrete results in the conservation and

management of fish stocks in the region. In his opening statement to the 2007 December

meeting of the WCPFC, the then chair of the Forum Fisheries Committee told the

gathering that FFA members felt that 'some members of the Commission have not

engaged in the Commission's work to date in the most constructive manner'.[60]

In their view, this behaviour had resulted in delay in advancing towards an

effective and robust management and conservation framework, particularly with

regard to bigeye and yellowfin tuna.[61]

Overall, however, the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat was of the view that much

progress had been made in the last year or two on improving the management of

fish stocks in the region though a lot of work remained to be done.[62]

4.33

At its 2008 December meeting, the WCPFC made notable gains with the

adoption of a number of proposals supported by the Pacific islands. They

included actions to reduce overfishing of bigeye and yellowfin tuna.[63]

Tonga also enlisted the support of the WCPFC to have a Taiwanese vessel deemed

as an illegal, unreported and unregulated vessel. This move was abandoned after

Taiwan agreed to pay the fine imposed by Tonga for the breach.[64]

4.34

Despite these positive moves to exert tighter control over the

exploitation of fish in the region, the then Chair of the Forum Fisheries

Committee recognised that while 'absolute commitment' to management and

conservation was required this must be matched by a commitment to implement

them.[65]

A study by the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security observed

similarly that:

...regardless of whether the WCPFC is the world’s most advanced

regional fisheries management organisation (RFMO), it all comes to nought if

members do not ‘own’ its outcomes and are not engaged in its deliberations.[66]

4.35

Thus, to protect their fishing interests, it is important for Pacific

island countries to have a decisive voice in the WCPFC and to secure the

support of all its members.

Capacity to engage in regional

organisations and implement policy

4.36

Clearly, Pacific island countries value their membership of the WCPFC

but unlike the developed countries, they have difficulty marshalling the

resources necessary to be active participants. Addressing a meeting of the

WCPFC, a representative from Tokelau referred to the major commitment of

resources needed, among other things, 'to work through the documents and get to

meetings'.[67]

The demands on the resources of Pacific island countries, however, go beyond

attendance at international meetings. The committee has already referred to the

lack of capacity in Pacific island countries to protect their EEZs from illegal

or unreported fishing activities.

4.37

A recent study published by the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources

and Security noted that 'while companies and nationals from DWFN reap the lion's

share of the benefits', Pacific island governments bear the overwhelming share

of the management costs.[68]

It stated clearly:

Increasing demands upon national governments to implement

necessary management and conservation measures is placing further pressure on

Pacific island governments and regional institutions. This combination of

events is exposing governance and institutional gaps at both the national and

regional level that undermine the ability of Pacific island countries to meet

these challenges and sustainably manage and develop their fisheries resources.[69]

4.38

According to the study, Pacific island countries will require a strong

institutional and governance capability to implement many critical elements

including fisheries conservation and management, vessel registration, licensing

and permits, gathering data, reporting and analysis, monitoring and enforcement,

administration, stakeholder participation and consultation, regional

cooperation, negotiation and advocacy.[70]

Indeed, Pacific island countries have an enormous task in effectively managing

their fish stocks and ensuring that the industry remains sustainable. Even PNG was prompted to note in 2007 that:

Our in-zone has now become so congested with management

measures to such as extent that we are now feeling the burden of management and

conservation measures which affects our legitimate development aspirations and

our sovereignty.[71]

4.39

Considering the size of Pacific island countries and the vast areas of

ocean over which they have jurisdiction, the task of managing, monitoring and

enforcing compliance is daunting.

Committee view

4.40

The fisheries sector is critical to the economic life of Pacific island

countries and makes a vital contribution to nutrition and food security in the

region.[72]

The committee notes the number of major problems Pacific island countries face

in ensuring the sustainable development of their fishery industry—the risk of

over-exploitation and the growing demand on their limited physical and human

resources to effectively oversee, manage and administer all aspects of the

industry. An island country on its own cannot hope to address the problem of

over exploitation, sustainable development, and illegal activity in the

fisheries sector. They need to obtain commitments and practical support from

DWFNs for the conservation of fish stocks and the sustainable development of

the fisheries industry. To do so, they require proficient advocates and

negotiators to represent their individual and collective interests and the

wherewithal to be effective members of regional organisations such as the

WCPFC.

Conclusion

4.41

Sound management of the agricultural and fisheries sectors is central to

the economic development of Pacific island countries. Furthermore, it is

critical that the use of these resources does not compromise the social,

environmental or economic well-being of future generations. Clearly, Pacific island

countries would benefit from assistance to become more self-reliant and

self-sufficient in their food supply by donor countries, such as Australia:

-

helping to raise awareness of the importance of sustainable

development;

-

continuing research and development in the area of food security

and resource management so that sustainable development of the land and sea is

based on the best scientific evidence and analysis available;

-

ensuring that the results of research are promoted as widely as

possible throughout the region through improved extension services;

-

building capacity in resource management;

-

providing funds and practical support to help Pacific island

countries monitor activities within their borders including their EEZ, enforce

agreements and prevent illegal exploitation of their resources; and

-

strengthening their capacity and that of the key regional

organisations to undertake activities in coastal and marine areas consistent

with their commitments to resource management and conservation.

4.42

In the following chapter, the committee turns its attention to

sustainable development in the forestry and mining industries before

considering environmental concerns arising from natural disasters and climate

change.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page