Chapter 3 - Structure and membership of APEC

Introduction

3.1

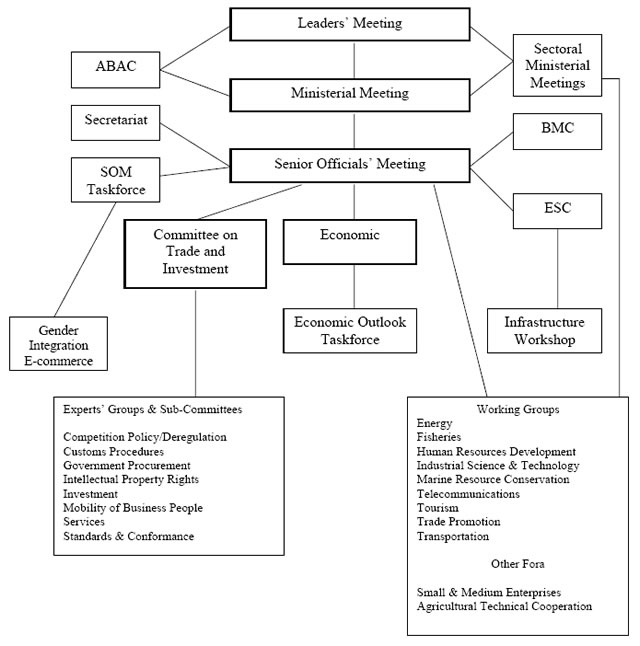

APEC is a fairly informal organisation with a

small secretariat based in Singapore. It operates at several levels: Leaders, Ministers, Senior

Officials, committees and working groups. The chairmanship of APEC rotates

annually among members with an ASEAN member of APEC chairing APEC in alternate

years. The member economy chairing the organisation hosts the Ministerial and

Leaders' meetings. An organisational chart of APEC is shown in Figure 3.1.

Leaders'

meetings

3.2

At the apex of the organisation is the Leaders’

meeting, which has been held annually since 1993, when President

Clinton hosted the inaugural

meeting at Blake Island, near Seattle, USA. At these

meetings, the Leaders focus on APEC’s goals, strategies for achieving them and

other key economic issues affecting the Asia Pacific region.

3.3

With the annual rotation of Chairs, each Chair

has striven to put his or her imprint on the direction taken by APEC at the

Leaders’ meeting. This has not only given considerable impetus to maintaining

momentum for APEC’s reform agenda but also has enabled the consideration of new

ideas and approaches. It has, however, as detailed elsewhere in this report,

resulted in some initiatives being downgraded or discarded once the Chair moves

on to the next incumbent.

3.4

The importance of the Leaders’ meetings cannot

be overstated as without the Leaders’ input in the development of the

organisation, much less would have been achieved. Their personal approval of

APEC’s direction and program has given credibility to the ambitious goals

embraced by APEC over a series of annual meetings. As APEC members have agreed

voluntarily to APEC’s long-term goals, implementation of measures to achieve

them depends on the goodwill of member economies in fulfilling their

responsibilities to APEC. The presentation annually of updated Individual

Action Plans is keeping the focus on the progress being made by all members

towards APEC’s long-term goals. Although peer pressure among the Leaders may

not always succeed in keeping all economies on the track of trade and

investment reform, it should do much to assist the process. For these reasons,

the personal involvement of the Leaders through attendance at the annual

Leaders’ meeting is an important element in keeping momentum for reform going

within APEC.

APEC

ABAC= APEC Business Advisory

Council

BMC = Budget and Management

Committee

ESC = Ecotech Sub–committee

SOM = Senior Officials

Meeting

3.5

The more informal nature of Leaders’ meetings

enables Leaders to discuss sensitive issues in a more relaxed atmosphere

without the expectation of specific outcomes often associated with bilateral

summits. This allows individual Leaders greater flexibility in their

negotiating positions than would be possible in bilateral meetings or in

multilateral negotiations towards legally-binding outcomes. APEC Leaders would

be more likely to achieve consensus on issues on which organisations like the

WTO would have great difficulty in reaching agreement.

3.6

The Leaders’ meeting also gives Leaders of all

APEC countries, irrespective of size or economic development, an opportunity to

meet and discuss regional economic matters with key economic Leaders. This

opportunity is not available in any other multilateral economic forum.

Consequently, this facility is attractive to non-members within the region, and

has been the inspiration for some membership aspirations on the part of

non-members.

3.7

Apart from the ‘formal’ business of Leaders’

meetings, the presence of so many Leaders in one place enables informal

business to be conducted in the margins of the meeting. For example,

negotiations towards the establishment of a United Nations force to restore

peace in East Timor after the ravages of pro-Indonesian militias were

facilitated by the presence of regional Leaders.

3.8

In recent years, however, APEC’s importance as a

regional institution has declined. Since the failure of the EVSL reforms in

1998, it is difficult to see any programs which APEC has embarked upon that

warrant holding an annual Leaders’ meeting. If APEC does not regain the

significant role it played in the early to mid 1990s, it is conceivable that

its annual leaders’ meetings will cease.

Ministerial

meetings

3.9

Ministerial meetings of APEC members, which are

generally attended by foreign and trade Ministers, have been held annually

since the first meeting in Canberra in 1989. This annual meeting ‘approves

APEC’s work program and budget, makes decisions on policy questions such as

APEC’s institutional structure and membership, and sets out directions for the

year ahead’.[1]

The meeting is held shortly before the Leaders’ meeting each year.

3.10

Meetings of other portfolio Ministers have also

been held, including Ministers responsible for education, energy, environment

and sustainable development, finance, human resources development, regional

science and technology cooperation, small and medium-sized enterprises,

telecommunications and information industry, trade, and transportation.

Senior

Officials' meetings

3.11

As APEC does not have permanent missions

assigned to a headquarters site, meetings of Senior Officials of APEC members,

generally at head or deputy-head of government department level, are held

regularly ‘to implement ministerial decisions and prepare recommendations for

future meetings. The Senior Officials also provide guidance to subsidiary

committees/groups’.[2]

A Deputy Secretary in DFAT holds the appointment of Ambassador to APEC, who is

the Australian Senior Official.

Committees

3.12

The work programs approved by Ministers at their

annual meeting are carried out by three committees, sub-committees, an ad hoc

policy-level group, ten working groups and other APEC fora.

Committee on Trade and Investment

3.13

The Committee is guided by a framework

agreement, which was endorsed at the 1993 Ministerial Meeting. The Committee:

aims to create an APEC perspective on trade and investment

issues and to pursue liberalization and facilitation initiatives. The committee

is responsible to senior officials for coordinating and implementing the

liberalization and facilitation components of the Osaka Action Agenda,

including work on Tariffs, Non-tariff Measures, Services, Deregulation, Dispute

Mediation, Uruguay Round implementation, Investment, Customs Procedures,

Standards and Conformance, Mobility of Business People, Intellectual Property

Rights, Competition Policy, Government Procurement and Rules of Origin.[3]

3.14

The Committee was also responsible for

development of EVSL initiatives and for a ‘strengthening markets’ work program

in 2000.

3.15

Responsible to the Committee are various

sub-committees and expert groups, namely:

- Standards and Conformance Sub-Committee;

- Sub-Committee on Customs Procedures;

- Investment Experts Group;

- Government Procurement Experts Group;

- Intellectual Property Experts Group; and

- Group on Services.

Economic Committee

3.16

At the 1994 Ministerial Meeting, the Ad Hoc

Group on Economic Trends and Issues was replaced by the Economic Committee. The

Committee ‘serves as a forum for exchanging economic data and views about economic

developments within the region. It also provides analysis of economic trends

and issues for APEC Ministers, and supports other APEC projects’.[4] The Committee’s work program in

1999 included:

the impact of the 1997 financial crisis on growth, trade and

investment; assessment of trade liberalization and facilitation; economic

outlook; and knowledge-based industries. The 1999 Economic Outlook

reviewed economic developments and prospects in the APEC region in the wake of

the Asian Financial crisis, and discussed some key issues arising from it.[5]

Budget and Administrative Committee

3.17

The Committee advises ‘Senior Officials on

operational and administrative budget issues, financial management, and project

management relating to the APEC Work Program’.[6]

Ecotech Sub-Committee (ESC)

3.18

This sub-committee was established in 1998 to:

assist the SOM in co-ordinating and managing APEC’s ECOTECH

agenda and identifying value-added initiatives for co-operative action. The ESC

advances effective implementation of that objective by consulting with, and

integrating the efforts of, various APEC fora through a results-oriented

approach that benefits all members.[7]

3.19

The sub-committee will ‘oversee the

establishment of an ECOTECH Clearing House that will enhance information flows between

the identification of ECOTECH needs and the capacity to provide appropriate

expertise to meet these needs’. Among other things, it will ‘monitor the

implementation of the Guidance on Strengthening Management of APEC ECOTECH

Activities and the ECOTECH Weightings Matrix by APEC fora to ensure

that ECOTECH projects submitted for funding meet key objectives and have

focussed outcomes.[8]

3.20

In 1999, Ministers decided to reconstitute the

Infrastructure Workshop as an ad hoc forum under the ESC.

Policy Level Group on Small and

Medium Enterprises

3.21

This Group was established in 1995 and oversees

activities for SMEs across all APEC fora, as there is a consensus in APEC that

free trade and economic globalisation have implications, challenges and

opportunities for SMEs.

Working

groups

3.22

Ten working groups have been established to

carry out a ‘range of practical cooperation activities (preparation of

guidebooks, information networks, training courses, technology transfer,

implementation of electronic data interchange, information exchange and policy

discussions)’.[9]

The working groups report to the Senior Officials’ Meetings and Ministerial

Meetings.

Energy Working Group

3.23

This Group:

works to promote cooperation on energy issues in the APEC region

... [It] aims to maximise the energy sector's contribution to economic growth

and energy security in the region. It is broadening its work program to

encompass more fully regional energy and environmental policy issues, and to

achieve greater involvement of the region's business sector in its activities.

The group’s work is organised under four “theme”: supply and demand; energy and

the environment; energy efficiency and conservation; research, development,

technology transfer.[10]

Fisheries Working Group

3.24

The aims of this Group are to ‘develop

region-wide approaches towards fisheries conservation, development and

marketing’. It is doing this by determining the optimum use of, and ‘trade, in

fisheries resources based on sustainable fisheries management practices’. It is

also promoting awareness of the significance of the Pacific Ocean’s fisheries

resources.[11]

Human Resources Development Working Group

3.25

This Group ‘works on the development of a

skilled, flexible workforce in an effort to enhance the economic growth of APEC

members’. It manages HRD projects ‘under broad programs covering industrial

technology, business management, economic development management, and

education’.[12]

Industrial Science and Technology Working Group

3.26

This Group ‘works to increase understanding of

factors affecting the development of industrial science and technology

(IS&T) and technology transfer, and to develop appropriate recommendations

for ministers’.[13]

Marine Resource Conservation

Working Group

3.27

This Group:

deals with the marine environment and conservation of economically

and ecologically important marine resources which affect industries including

urban development, fisheries and tourism ... [It] is identifying problems and

control strategies (coastal pollution, harmful algal blooms, hazardous

substances, tainting of fish and other products, deterioration of beaches,

reefs, mangroves, seagrass beds) and opportunities in the region for integrated

coastal zone management and planning associated with settlement and population

growth along the coastlines and adjacent watersheds.[14]

Tourism Working Group

3.28

This Group ‘works to foster economic development

in the APEC region through sustainable tourism growth’. It identifies and seeks

to ‘remove impediments to regional tourism trade’; explores ‘linkages between

tourism and the economic development of the region’; explores ‘successful

management strategies for the sustainable development of tourism in

environmentally sensitive areas’; develops ‘ways of promoting human resource

development’; and facilitates 'information exchange among members’.[15]

Telecommunications Working Group

3.29

This Group ‘aims to expand telecommunications

services and encourage the adoption of new and compatible telecommunications

technologies in the region, including through further telecommunications trade

liberalisation and facilitation’. Work is organised under five ‘themes’: ‘data

compilation, electronic commerce, human resource development and

infrastructure’, as well as ‘standards’, which was a later addition. It is

developing ‘a model mutual recognition agreement on certification of

telecommunications terminal equipment, a regional framework for electromagnetic

compatibility, and regional competency standards for telecommunications

industry vocational training’. It is also assisting ‘small and medium enterprises

in the implementation of electronic commerce’.[16]

Trade Promotion Working Group

3.30

This Group is aiming to expand regional trade

through co-operation among trade promotion agencies and consultation with

business. It is helping business to gain access to APEC information and

encouraging business to participate in APEC policy making. The Group ‘has

established the “Asia Pacific Business Network” ... an informal business

grouping with a particular interest in networking among the region’s small and

medium sized enterprises, and conveying their views to APEC’.[17]

Trade and Investment Data Working Group

3.31

This Group ‘aims to increase the utility and

reliability of regional trade and investment data’. It is doing this by:

establishing a database of these statistics covering all APEC

economies and is encouraging member economies to collect statistics using

standard concepts and definitions developed by international organisations, to

harmonise data collection methods and practices, and to ensure that

construction of databases does not duplicate work in other international

organisations.[18]

3.32

The Group is also preparing ‘inventories and

data matricies by APEC partners on bilateral international trade in services

and direct investment statistics. Data availability by partners is seen as the

main limiting factor in developing comprehensive bilateral data matrices in

these fields of statistics’.[19]

Transportation Working Group

3.33

This Group aims to promote an ‘efficient and

integrated region-wide transportation system that will enhance regional growth

and economic inter-relationships for the common good of APEC economies’.[20]

APEC

Secretariat

3.34

The Secretariat, which is based in Singapore, is

headed by an Executive Director from the country chairing APEC. He or she

serves for one year. The Secretariat has 23 seconded professional staff from

member economies and a similar number of locally recruited support staff.

3.35

The Secretariat’s operational plan comprises six

outputs and four services based on a Statement of Business, approved by member

economies. The Statement of Business comprises the following:

- The Secretariat is the core support mechanism for the APEC

process.

- The Secretariat provides advisory, operational and

logistic/technical services to member economies and APEC fora to coordinate and

facilitate conduct of the business of the organization.

- On behalf of member economies, it provides preparatory advice on

formulation of APEC projects, manages project funding and evaluates projects

funded from the APEC Operational and TILF accounts.

- The Secretariat produces a range of publications, liaises with

the media and maintains a website to provide information and public affairs

support on APEC’s role and activities, including specific outreach efforts to

business. It acts on behalf of APEC members as and when directed.

- The Secretariat maintains a capacity to support research and

analysis in collaboration with APEC Study Centres and PECC as required by APEC

fora.

- The Executive Director is responsible to APEC Senior Officials

through the SOM Chair and manages the Secretariat in line with priorities set

by SOM on behalf of Ministers.[21]

APEC

Business Advisory Council

3.36

At the inaugural Leaders Meeting in November

1993, it was agreed to set up a Pacific Business Forum to strengthen links

between APEC and the business community. The Forum provided the Leaders with

advice and recommendations on trade and investment liberalisation and on

business facilitation. In 1995, the Leaders replaced the Forum with the APEC

Business Advisory Council (ABAC), a permanent business advisory body.

3.37

Each member economy may appoint three

representatives to ABAC, one of whom must be from a small to medium-sized

enterprise. Australia’s current representatives on ABAC at the time of the

Committee’s hearings were Mr Michael Crouch AM, Chairman and Managing Director

of Zip Industries Australia; Mrs Imelda Roche AO, Co-Chairman of Nutri-Metics

International; and Mr Malcolm Kinnaird, Executive Chairman of Kinhill Engineers

Pty Ltd. Since then, Mrs Roche was replaced by Mr David Murray, Managing

Director of the Commonwealth Bank.

3.38

ABAC's main objectives are to:

- help APEC strengthen its links to the regional business

community;

- allow the business community to advise APEC on its priorities in

relation to the implementation of the Action Agenda;

- respond directly to requests from APEC for advice on business

reviews on specific issues.[22]

3.39

ABAC provides a report to the Ministerial and

Leaders’ meetings each year with advice on integrating and facilitating

business within the region. In 1996, in its capacity as APEC Chair, the

Philippines emphasised business activities:

President Ramos initiated the practice of ABAC representatives

meeting with APEC Leaders prior to the Leaders meeting itself and also

initiated a much larger APEC Business Forum in association with the

Ministerial/Leaders’ meetings, continuing the trend towards closer integration

of private sector networking in the region.[23]

Eminent

Persons Group

3.40

At the September 1992 Ministerial meeting in

Bangkok, it was agreed that an Eminent Persons Group be established ‘to

enunciate a vision for trade in the Asia-Pacific region to the year 2000,

identify constraints and issues which should be considered by APEC, and report

initially to the next Ministerial Meeting in the United States in 1993’.[24]

3.41

The Group made reports to the Ministerial and

Leaders’ meetings until it was wound up at the November 1995 meetings when ABAC

was established.

Membership

of APEC

Membership history

3.42

Twelve member economies attended the first APEC

Ministerial Meeting in Canberra in November 1989—Australia, Brunei Darussalam,

Canada, Indonesia, Japan, Republic of Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, the

Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and the United States. It was clear, however,

even at this early stage in APEC’s development, that its membership would be

expanded.

3.43

In the Chairman’s Summary Statement, which was

issued at the end of the meeting:

Ministers have noted the importance of the People’s Republic of

China and the economies of Hong Kong and Taiwan to future prosperity of the Asia

pacific region. Taking into account the general principles of cooperation

identified above, and recognising that APEC is a non-formal forum for

consultations among high-level representatives of significant economies in the

Asia Pacific region, it has been agreed that it would be desirable to consider

the involvement of these three economies in the process of Asia Pacific

Economic Cooperation.

3.44

At the 1991 Ministerial Meeting, APEC became the

first international organisation to include the ‘three Chinas’—Peoples’

Republic of China, Taiwan and Hong Kong. According to DFAT:

The task of drawing them into the process was a difficult one,

requiring agreement both on the nomenclature of Chinese Taipei and Hong Kong

after its handover, and on arrangements for Chinese Taipei’s representation at

Ministerial meetings.[25]

3.45

At the 1991 Ministerial Meeting, the Ministers

also declared that:

Participation in APEC will be open, in principle, to those

economies in the Asia-Pacific region which:

- have strong economic linkages in the Asia-Pacific

region; and

- accept the

objectives and principles of APEC as embodied in this Declaration.

Decisions regarding future participation

in APEC will be made on the basis of a consensus of all existing participants.[26]

3.46

At the September 1992 Ministerial Meeting in

Bangkok, the APEC Ministers reiterated the membership declaration made at the

previous meeting and ‘expressed the view that APEC was entering a phase when

consolidation and effectiveness should be the primary considerations, and that

decisions on further participation required careful consideration in regard to

the mutual benefits to both APEC and prospective participants’. The Ministers

noted, however, ‘the emerging reality of an integrated North American economy

and the growing linkages between that North American economy and the rest of

the Asia-Pacific region’ and asked officials to examine the case for Mexico’s

membership. Mexico and Papua New Guinea were both admitted in 1993, and Chile’s

participation was agreed at the 1993 Ministerial Meeting, to take effect at the

1994 Ministerial Meeting. At the same meeting, the Ministers decided to defer

any further applications for membership for three years while officials

considered membership issues.

Russia’s participation in APEC

3.47

At the Ministerial Meeting in November 1997, it

was decided that three further economies—Peru, Russia and Vietnam—would take

their places in APEC in November 1998. It was also agreed to institute a

ten-year moratorium on any further increase in membership.

3.48

The decision in November 1997 to extend

membership to Russia to take effect in November 1998 was unexpected. Although

Russia has a Pacific Ocean seaboard, that region is underdeveloped compared

with many other parts of the nation. In most respects, Russia is firmly

oriented towards Europe rather than Asia Pacific. Although its Pacific

territory offers development prospects, it has languished, and there is no

evidence to suggest early rejuvenation of this area. It is difficult,

therefore, to understand the logic of the decision in the light of the APEC

membership criterion that an economy ‘have strong economic linkages in the

Asia-Pacific region’. Although Russia may accept the objectives and principles

of APEC’, the ability of Russia to meet APEC objectives and obligations is

highly questionable. At this stage, it is facing huge economic and political

problems in transforming its old communist-structured economy into a modern

market economy. The decision has all the hallmarks of one that was made for

global strategic reasons rather than for Asia Pacific regional economic

co-operation. The Federal Opposition disagreed with APEC’s decision to include

Russia in APEC.

3.49

Professor Drysdale told the Committee that there

are both costs and benefits in Russia’s admittance. Russia’s close association

with the major players in the region will have the potential benefit of

providing the region with greater political security and stability in the

longer term.[27]

Inevitably, over time, the APEC economies will have to deal with Russia in a

political sense. By being part of APEC, relations between Russia and the other

APEC economies might be managed in a more beneficial way. The main question

mark in the near future is the role Russia might play in pursuit of the APEC

economic agenda and the management of economic crises, such as the current East

Asian financial crisis.

3.50

It is unlikely that Russia’s admittance will

improve the cohesiveness of APEC. Dr Elek drew attention to the fact that

Russia’s trade with Europe is larger than that with APEC economies and the

potential difficulties for APEC as Russia becomes more integrated into the

European economy:

we are going to need to think through some kind of guiding

principles so that Russia does not by default, or without really thinking it

through, enter into more relationships with Europe which actually discriminate

against the rest of its APEC partners, which is the way Europe usually enters

into trading arrangements.[28]

3.51

The decision has, of course, already been made.

The important thing now is to ensure that potential problems associated with

Russia’s membership are managed in such a way as to enhance the APEC concept

and its trade liberalisation goals. Ms Fayle told the Committee in March 1998

that:

There was a consensus in the leaders meeting to admit three new

members. Australia has signed on to that consensus and we are enthusiastic

about working with the new members, including Russia, to ensure that they make

the transition into APEC in as effective and efficient way as possible. We are,

for example, sending an expert on IAPs and sectoral liberalisation to Russia to

assist them at the technical level with some of that work. We are making a

conscious effort to ensure that the new membership does not involve too much

greater time consuming effort on the part of APEC and that it does not hold up

making progress in some of these areas that are important to us.[29]

3.52

The Committee believes that APEC should

encourage Russia not only to play a constructive role in APEC but also to

develop economic links within the Asia Pacific region through the development

of the economy of its Pacific territories.

Future membership policy

3.53

Membership has been a sensitive issue for APEC

as a number of economies on both sides of the Pacific have sought to become members,

including some, such as India, which are not Pacific-littoral economies.

3.54

Two questions in particular have exercised the

minds of APEC economies in relation to membership: the size and the actual

composition of APEC.

3.55

It is always difficult to decide on the optimum

size of an organisation, particularly when there is pressure from potential

members to allow their membership aspirations to be realised. In any

organisation, it becomes more difficult to achieve consensus as membership

increases, even when there is a general homogeneity among members. The great

diversity of political systems, population sizes, stages in economic

development and cultures among APEC economies makes decision-making more

difficult. This has been offset by adopting a policy of lack of prescription,

which has made it easier for members to agree on long-term goals and work

programs. But, as membership and therefore the diversity of interests increase,

unanimity will be more difficult to achieve. This, in turn, may slow the pace

of reform.

3.56

Fred Bergsten, the former Chairman of the APEC

EPG drew attention to the tension between deepening and broadening any

international institution:

It is clearly more difficult for any international institution

to deepen its substantive links if it has more members and it must divert part

of its time to the process of expansion. Europe has always resolved the dilemma

by completing its next stage of integration (deepening) before accepting new

members (broadening).[30]

He went on to advocate APEC following a similar course on

membership to the one taken by the European Union. He warned that the

participation of any large country, which had not yet got far down the track of

liberalisation, might complicate APEC’s ability to achieve progress.

3.57

In October 1997 (before the most recent increase

in membership), the Australian Ambassador to APEC, Mr Grey, told the Committee

that there was an upper limit on membership from a practical point of view. He

went on to say that ‘we have not reached that now, and it may well be that a

couple of new additions would not change that dramatically but it should, in

our view, be kept as small as possible–in some respects, the smaller the

better’.[31]

3.58

At DFAT’s second public hearing on 30 March

1998, Ms Fayle, First Assistant Secretary, Market Development Division, said

that:

Australia has always opposed excessive expansion of APEC

membership. We had a well-known position that we did not think that APEC should

expand too quickly simply because that did make things unwieldy and difficult.

We felt there was already a large enough agenda and a large enough membership

to bite off the sorts of things we had on our plate ... It was simply that we

were keen to ensure that the pace of membership expansion was an appropriate

one.[32]

3.59

In view of the nature of its membership, APEC

has made remarkable progress in agreeing to long-term goals and a framework for

achieving them. These goals include sensitive areas that have so far defied all

other attempts at resolution. There is still much to be done, not only in APEC

but also in other related fora, such as the WTO, before these goals are reached

within APEC’s 2010 and 2020 deadlines. Keeping APEC to a manageable size will

facilitate trade and investment liberalisation and facilitation objectives. The

ten-year moratorium is evidence of APEC’s realisation that a larger

organisation might jeopardise achievement of these objectives. The Committee

believes that a membership of more than 21 economies would not be helpful in

attaining APEC’s goals.

3.60

It is inevitable that other economies will seek

to join APEC before the expiry of the moratorium. The Committee believes that

pressure to break the moratorium should be resisted, unless significant changes

in circumstances dictate a change in membership policy. For instance, before

the end of the ten-year period, and however unlikely that might seem at the

moment, APEC and WTO might achieve important breakthroughs in sensitive areas,

bringing the Bogor goals well within APEC’s grasp. A further small enlargement

of APEC’s membership at that time might not be considered to hinder completion

of APEC’s work program.

3.61

Unlike preferential free trade blocs,

non-members are not discriminated against in their trade and investment links

with APEC members. The adoption of open regionalism extends liberalisation and

facilitation benefits on a most favoured nation basis to all non-members. APEC

processes are also open to scrutiny outside the organisation; outcomes of

meetings are published, as are details of Individual Action Plans.

3.62

There is no reason for an aspiring member not to

undertake the objectives and obligations of APEC members. This would include

the voluntary submission of an Individual Action Plan, updated annually, as is

the requirement for members. In the view of the Committee, unless an Asia

Pacific economy were to do this, it should not be considered for membership.

3.63

In view of the added difficulties involved in an

enlarged membership, economies that have demonstrated over time their

commitment to APEC goals should be in a much stronger position to have their

applications for membership approved than those which only give lip service to

those goals.

3.64

The interests of APEC economies will be served

if non-APEC economies could be encouraged to embrace APEC’s goals. Ultimate

membership of APEC is one incentive to do this. However, other ways of

accommodating the needs and aspirations of other Asia Pacific economies should

also be found without compromising the membership moratorium. One option is an

extension of observer status to non-member Asia Pacific economies that embrace

the APEC mission and all its obligations. APEC would need to satisfy itself

that a non-member is meeting its obligations and will continue to do so once

observer status is granted. This measure would be regarded as a preliminary

step towards membership.

3.65

A second option is greater representation of

non-member economies, which embrace APEC obligations, in the APEC work program.

There has been limited representation of non-APEC economies on APEC working

groups and project teams. The inclusion of additional relevant people from

these economies would help to give them a sense of inclusion in the APEC

process and reinforce their commitment to APEC goals.

Membership for Indian Ocean

littoral economies

3.66

The other membership question raised in the

inquiry was whether membership should include Indian Ocean littoral economies,

particularly India, which has sought membership of APEC. Professor Garnaut told

the Committee:

I would have thought that India’s claims were stronger than

Russia’s claims. I have thought that for some time. While holding that thought,

I did not think that it was crucial for India to be a member, so long as APEC

members, and APEC itself, were cognisant of the huge importance of the success

of the reforms in India that got under way in the 1990s.

Because trade liberalisation within APEC is within the framework

of open regionalism it does not cut India out. India could do with a lot of

liberalisation within that framework itself. I think it might be helpful to the

political economy of reform in India if particular APEC countries–and why not

Australia–engaged in rather active discussion with India of the advantages of

parallel liberalisation and, at the same time, deliberately built business

links to take advantage of the new opportunities that would emerge from that

process.

Open regionalism in South Asia alongside liberalisation within

an open regional context in APEC would be a very productive basis for regional

trade expansion in India, at the same time as opportunities were expanded for

links with the Asia-Pacific region. I would like to see us active in

discussions with India in those ways rather than talking of further dilution of

APEC.[33]

3.67

India is not being disadvantaged by not being a

member of APEC. The adoption by APEC of open regionalism as the basis for trade

liberalisation means that South Asian economies are not subject to

discrimination in trade with and investment in APEC economies. The Committee

believes that India and other South Asian economies, which have an interest in

joining APEC, have an opportunity during the moratorium to demonstrate their

credentials by fulfilling voluntarily the requirements of membership.

3.68

In the same way as Australia is helping Russia

with its Individual Action Plan, similar assistance should be extended to India

and other non-member Asia Pacific economies embarking on trade liberalisation,

should they wish to avail themselves of it. As Professor Garnaut intimated,

there may also be commercial spin-offs available to both sides from such

cooperation.

Conclusion

3.69

The moratorium gives APEC a breathing space to

concentrate on its three pillar agenda. With 21 disparate economies already

participating in its ambitious program, it will take all the ingenuity and

cooperation of members to reach those distant Bogor goals along a path strewn

with obstacles. The addition of new participants would only serve to make the

task more difficult to complete. However, in the longer term, it may be both

feasible and desirable that APEC membership be expanded to include the

participation of other Asia Pacific economies that meet the membership

criteria.

Recommendation

The Committee recommends that the

Australian Government work to have APEC adopt a position of:

- accepting new members only after they

have demonstrated their support for APEC policies and goals by voluntarily

complying with APEC obligations (including submission and annual updating of

Individual Action Plans) for two years;

- granting observer status to potential new

members which meet their APEC obligations;

- allowing greater participation in APEC’s

work program by potential new members; and

- providing assistance to potential new

members to adopt APEC policies, goals and obligations.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page