Nature and underlying causes of joblessness in remote communities

Introduction

3.1

In a 2010 paper, McRae-Williams and Gerritsen explained the unique economic

and employment challenges within remote communities:

There are limited employment opportunities with a significant

gap between the size of the labour force and the number of jobs generated in

the local economy as well as inadequate physical infrastructure for many

economic development proposals. Low levels of education, limited opportunities

for training, poor health, transport difficulties, and issues of alcohol and

drug abuse are also factors affecting employment capacity.[1]

3.2

Similarly, a 2014 study by the Australian Institute of Health and

Welfare found that Indigenous Australians generally experience multiple

barriers to economic participation, including lower levels of education, poorer

health and more difficulties with English (especially in remote areas), higher

rates of incarceration, inadequate housing and accommodation and lack of access

to social networks that may help to facilitate employment.[2]

3.3

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has found that, after

adjusting for the combined effect of age, education levels and remoteness, the

gap between unemployment rates decreased by more than half, but Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander people were still twice as likely as non-Indigenous

people to be unemployed (10.8 per cent compared with 5.5 per cent).[3]

3.4

This chapter focuses on a number of the key factors that cause

joblessness in remote communities:

-

Remoteness;

-

Younger age profile;

-

Educational status;

-

Lack of labour market economy (including government procurement);

-

The impact of trauma;

-

Cultural and family obligations; and

-

Reluctance of some businesses to employ Indigenous people or

employ locally.

Remoteness

3.5

As noted earlier in the report, the CDP is designed specifically for

remote Australia.[4]

Remoteness is defined by the ABS as a factor of accessibility and distance from

the nearest urban centre.[5]

3.6

The ABS's 2014 analysis of the gap in labour market outcomes for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people found that:

-

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were twelve times

as likely (22.1 per cent) as non-Indigenous peoples (1.8 per cent) to live in

remote or very remote areas (see Figure 3.1 below); and

-

labour force participation in remote areas varies with age, so

the combination of younger age and remoteness may have a greater effect on

outcomes.[6]

3.7

In 2014 ̶

15:

-

the unemployment rate for Indigenous Australians was 21 per cent,

an increase of 4 percentage points from 2008 and 3.6 times then the

non-Indigenous unemployment rate of 6 per cent; and

-

37 per cent of Indigenous Australians in remote areas were

employed compared with 52 per cent of Indigenous Australians in non-remote

areas (see Table 3.1 and Figure 3.2 below).[7]

Figure 3.1—Population

distribution across Remoteness Areas by Indigenous status[8]

Table 3.1—Labour force status of

Indigenous Australians aged 15̶

64 years, by remoteness, 2014 ̶

15[9]

Figure

3.2—Employment

rate by Indigenous status persons aged 15–64 years, by remoteness, 2014–15[10]

3.8

The committee heard that remoteness can lead to disengagement of

communities from the broader economy of Australia and 'make them much more

reliant on the public purse to help them sustain what they have and to increase

the possibilities for them'.[11]

Assistant Commissioner Paul Taylor of the Queensland Police told the committee that

remoteness and isolation can cause a range of 'hurdles' especially during a

young person's development which can impede a person's capacity to take on a

job.[12]

Practical challenges—such as needing to travel to buy groceries and attend

medical appointments as these services are either too expensive or simply not

available in remote communities—are often not accommodated as part of CDP.

3.9

Ms Vanessa Thomas, Director at the Nurra Kurramunoo Aboriginal

Corporation and resident of the remote community of Mulga Queen (Western

Australia) described having to travel 140 kilometres to purchase affordable groceries

in the nearest town of Laverton or over 500 kilometres to reach Kalgoorlie (the

closest regional town) for a medical appointment and being breached by the

local CDP provider.[13]

The need to travel such distances for everyday services is not compatible with

the five hours per day required of CDP participants. Ms Thomas noted the

breaches that CDP participants incurred as a result of this necessary travel.[14]

Younger age profile

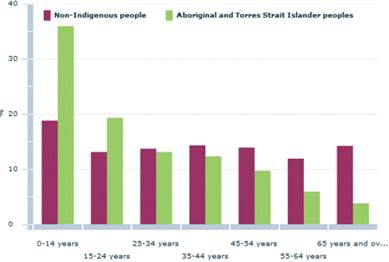

3.10

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have a younger age profile

than non-Indigenous people, as shown in Figure 3.3 below.

Figure 3.3—Age structure by

Indigenous status[15]

3.11

Unemployment rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were

higher than those for non-Indigenous people, in all age groups. However, the difference

was largest for young people aged 15–24 years (31.8 per cent for Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander people, compared with 16.7 per cent for non-Indigenous

people).[16]

3.12

The younger age profile of a remote community combined with the higher

prevalence of unemployment in the younger age cohorts results in higher levels

of unemployment in those communities compared to their non-remote counterparts.

Educational attainment

3.13

There have been a range of studies that underscore the key reasons for

lack of success in the mainstream labour market for Indigenous Australians.

These highlight the critical importance of educational attainment in employment

disparities.[17]

According to the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR) at the

Australian National University, the difference in employment outcomes in remote

and non-remote locations is likely to involve the differential access to

educational institutions for such areas.[18]

3.14

Research by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, supported by

ABS analysis, found that the difference in educational attainment between

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous people was a critical

factor in the difference in employment rates:

Our findings...underscore the critical importance of

educational achievement to economic participation.[19]

3.15

The lack of educational opportunities has long been recognised as according

to the 1996 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, as many as 10 000

to 12 000 Indigenous students aged between 12 and 15 years living in remote

communities did not attend education facilities because of a lack of

post-primary schooling facilities within a reasonable distance of their home. In

a 1996 submission, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission argued

that a key reason preventing Indigenous students from leaving their home

communities was inadequate supports in regional and metropolitan cities:

The reluctance of Indigenous students to leave their home

town was due to a lack of financial and emotional support in the cities.[20]

3.16

Ms Victoria Baird of Save the Children noted that one of the key

difficulties for CDP participants maintaining employment is that 'they lack

education or skills'.[21]

Lack of education was described as an intergenerational issue, with some

witnesses noting that previous generations had very limited education, with

many historically not allowed to continue their education beyond primary school.[22]

3.17

Ms Tina Carmody, the Working Together Co-ordinator at Kalgoorlie Boulder

Chamber of Commerce and Industry noted that educational outcomes in remote

indigenous communities are very different to those in non-Indigenous Australia.

Ms Carmody acknowledged that, in some instances, CDP has helped to provide

some basic literacy and numeracy programs. Notwithstanding these minor gains,

significant challenges remain:

When you go out there in country, where English is the

second, third or fourth language, that level of education presents a problem for

finding employment. So that is another barrier. Our level of education is

totally different from white man's definition of 'level of education', and I do

not believe that is considered.[23]

3.18

This view was supported by others who noted that there are many in

remote communities who do not speak English as their first language:

Most of the people that we work with in Kununurra would be

speaking Kimberley Kriol as their first language not Australian standard

English. Obviously, in the further outlying communities you have people who

have Aboriginal languages as their first language.[24]

3.19

Ms Ada Hanson of the Kalgoorlie Boulder Aboriginal Residents Group

(KBARG) expressed the view that educational disadvantage is perpetuated because

remote Indigenous communities 'are receiving substandard education, and it's

not delivered in the language of their people'.[25]

Ms Hanson elaborated:

It stems all the way down to the education that they're given

as children. It's not within their language, so it's their understanding of what

is being taught. As a child under five you can be who you are: you speak your

language, whether it's English or Chinese or whatever it is. Then you go to

school, and in Australia that's in English, so you are completely changing the

way you have grown up. When you are growing [up] you're getting all the tools

and resources necessary to be able to contribute to society. Then it stops when

you get to school, because you can't understand what's happening. It starts

from there, basically, and then just continues. When they get into their late

teens or early adulthood they're just not ready with the tools. Then the

training, of course, isn't provided within the context of their lives, I

suppose.[26]

3.20

Mr Martin Sibosado, Chairperson of Aarnja, observed that educating and

empowering a person with an education and skills to successfully enter the job

market is not a short term project. Many community organisations have educated

and trained local Indigenous tradespeople in remote locations, but it takes

time and a co-ordinated approach:

I can tell you it took 20 years to actually establish

Aboriginal plumbers, Aboriginal builders. That's how long it takes to take

someone through education right through to actually getting a trade certificate

and into business. It can be done, but it could be done a whole lot quicker if

we had more coordination of our programs.[27]

Lack of labour market economy

3.21

As noted earlier, educational attainment through skills and experience

is an important precursor to job-readiness. Equally as important though is the

existence of a functioning economy—that is, the pathways and opportunities to

apply these skills and experiences. Mr Hans Bokelund, CEO of the Goldfields

Land and Sea Council made the following observation:

I understand the government's position on education, trying

to get our Aboriginal children through to year 12, but I think one of the

issues I have is if there are no pathways afterwards, infrastructure, job

market in the remote communities, we're going to have more despair, more suicides.[28]

3.22

The ABS has found that work opportunities in regional and remote areas

of Australia differ from those in major cities because of the nature of their

labour markets, with differing types and availability of work.[29]

Mr Peter Strachan also observed in his submission that 'remote areas generally

have an underdeveloped labour market where people often do not actively look

for work and therefore are not classified as unemployed, even though they are

not working and might indeed prefer to work if the labour market were

different'.[30]

3.23

Dr Inge Kral of the Australian National University offered her view of

the employment challenges in remote communities:

Ultimately, despite all these policy initiatives in the

employment domain in remote regions, the structural conundrum remains the same.

Remoteness and distance combined with unique ecological and historical

circumstances mean that there is essentially still no labour market economy in

most remote communities. Coupled with this is the reality that social and

cultural ties to traditional land compel many remote groups to stay living on

the land of their ancestors. Therefore remote Aboriginal people are less likely

to move to other locations seeking employment.[31]

3.24

This view was echoed by Mr Cameron Miller, CEO of the Ngurratjuta Pmara

Ntjarra Aboriginal Corporation:

The labour market in the remote areas is diminishing. It's

never been there, but it's getting a lot harder. You've got your core services,

which have employment opportunities available, but they're never consistent.

We've been able to place people into employment, but it's generally short term.

We struggle in the remote communities because we [don't] have

access to facilities—that is the biggest thing—and access to industry. So to

create an industry in one of our hub communities or main communities, it's a

multi-million dollar task. It's not just a matter of setting up a small shop

and creating competition for the other shop that's already there, struggling,

it's long term. We haven't come across an industry to create, other than

tourism, and that's where we're basically focusing our efforts as a whole, not

specifically for CDP, but we see that there'll be merit coming out of that in

the next three to five years.[32]

3.25

Professor Altman summarised key policy challenges in addressing

joblessness in remote communities:

-

the disparity between jobs and the Indigenous population in

remote and very remote regions is massive (the employment to population ratio

for Indigenous persons was 37 per cent and 83.4 per cent for non-Indigenous

people);

-

the extremely high non-Indigenous employment rate in rural and

remote regions reflects non-Indigenous migration to take up employment, largely

to administer government programs for Indigenous improvement; and

-

Indigenous labour mobility as a policy solution fails to

recognise people's attachment to country and communities, and a lack of

evidence that those who do move improve their employment prospects.[33]

Government procurement

3.26

Many witnesses were asked about the role of government procurement in

providing employment opportunities in remote locations. Some acknowledged that

most government contracts are centred around the metropolitan centres

reflecting where most government business is undertaken.[34]

Notwithstanding this, the committee received evidence which showed that where

government contracts are being undertaken in remote locations, remote

communities are missing out on the opportunity to be involved:

On the Dampier Peninsula, just north of Broome, where our

communities live, the Commonwealth has provided $53 million to the Northern

Australia Roads Program and the state's provided $12 million. The road contract

is starting. No Aboriginal people have got a job. [Kullarri Regional

Communities Indigenous Corporation] trained 10 people in preparation 12 months

ago for that contract, and not a single person has gotten a job at this stage.

They promise us, 'Next year you'll have a job.' Secondly, they say, 'Your

people aren't skilled,' but we say, 'They've been through VET cert III.' That's

just an example when you're talking about procurement.[35]

3.27

In Alice Springs, the committee heard that Indigenous employment targets

are a compulsory requirement in some government procurement contracts. Mr

Michael Klerck, Manager of Social Policy and Research at Tangentyere Council

described how these targets are being used as part of the tendering process,

but not being monitored as contracts are executed:

With respect to a lot of Northern Territory government

procurement processes, generally they're weighted on the basis of different

selection criteria, and local employment is one of those selection criteria,

but unfortunately at times, particularly under the previous [Territory] government,

we found that price seemed to take priority in terms of the way contracts were

awarded. And then once awarded, there may be particular key performance

indicators. For example, for remote tenancy management, there was a key

performance indicator of 50 per cent Aboriginal employment, but, after

significantly reviewing project performance information reports from some non-Indigenous

for-profit providers, it would seem with those that 50 per cent Aboriginal

employment target was not being met. We're talking about an achievement of

maybe 19 per cent of the Aboriginal employment target in some cases, and less

than half of that is local Aboriginal employment in the remote communities. On

one level it seems to be a priority in selection criteria and key performance

indicators, but in other respects it doesn't seem to actually turn out that way

a lot of the time.[36]

3.28

This view was echoed in Queensland by Ms Katie Owens, Manager at Rainbow

Gateway who noted that non-compliance against the Indigenous employment

requirement is:

...compounded by the fact that the government procurement processes—for

example, the requirement to employ local people through local contractors—are

often unmonitored and unreported against.[37]

3.29

Ms Owens elaborated:

In my experience with the procurement

that has happened in the past throughout our communities, a lot of times when

anything involves a contractor—say we're doing building repairs and maintenance on the houses—all of a sudden a contractor turns up into community

and they have cursory conversations with us about the suitability of our

participants. There needs to be an early identification and discussion amongst

a lot of people in community, including the key stakeholders, as well as the

participants and any government departments that are actually involved in that,

so that we can start a process of having our jobseekers or participants trained

to be able to go in to actually get that job...[38]

3.30

There appears to be an inconsistent approach to the use of Indigenous

employment targets both at a state and federal level. The Department of the

Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) noted that the Australian Government proposes

to have requirements for Indigenous employment targets for road projects in

northern Australia. However, these requirements would not be universal with PM&C

acknowledging that such requirements would only apply to projects in northern

Australia—as part of the Government's broader policy to develop northern

Australia—and would not include projects in parts of southern Australia

including the Goldfields region of Western Australia.[39]

3.31

The use of a headcount for Indigenous targets rather than a calculation

of the number of hours worked by Indigenous employees is another approach which

reduces the Indigenous component of a workforce working on a specific project

or contract. Mr Matthew Ellem, General Manager at Tangentyere Employment

explained:

I think there is an issue that there is not a consistent

reporting. In some contracts it will be the number of people out of the

workforce but not necessarily the number of hours. So what we see happening

with some projects is that they will employ half a dozen labourers from us as

casuals, but they're getting casual hours and fewer hours than their normal

workforce. It doesn't seem that government actually ends up asking what

proportion of wages went to Indigenous workforce. It is just a headcount, with

no qualitative evaluation of how much work or how much in wages the Indigenous

workforce got compared to the non-Indigenous workforce.[40]

3.32

Another witness noted that in other cases contractors who do not meet Indigenous

employment targets often forego a bonus; however, the bonus is insufficient to

incentivise meeting the employment targets.[41]

A lack of coordination on government contracting work was also flagged as a

reason why locals were missing out when governments were spending money, in

particular on roads and housing in remote locations. Quick delivery of projects

is often undertaken at the expense of using local labour.[42]

3.33

This lack of coordination extends not only to mainstream companies, but

also to Indigenous-owned enterprises. Mr Sibosado noted that there is room for

improvement:

There was another thing that struck me when I was talking to

some of the successful and award-winning Indigenous businesses. I got to

saying, 'How far do you go?' They said, 'We've actually got contracts in your

country.' I said: 'How's that? How come you're not talking to local people,

CDPs, around creating employment?' They said, 'We don't know who to talk to.'

Obviously they are Koori people from Sydney. So I said: 'Here's a card. Give us

a ring and we'll connect you up with everybody.' There may be a few jobs to

grab.[43]

3.34

The committee were also told that it is difficult for remote community

organisations to compete for contracts against more experienced businesses and

organisations who are better able to demonstrate their capacity to complete a

contract. Mr Mark Jackman, General Manager of the Regional Anangu Services

Aboriginal Corporation, described the need for local groups to be given a

chance to win some work, employ some locals and demonstrate their capabilities:

For us, it is about procurement and creating the

opportunities. If we don't get opportunities we can't engage. There are major

roadworks on the APY Lands and we're largely shut out of that cycle. It's just

about creating those opportunities. When housing contracts come along, we put

in a big tender and we might just miss the post. My conversations with

governments are: 'You don't have to give us a big contract but give us maybe

two houses so that we can prove our worth.' You need to start somewhere, but it

is about our organisation getting that start. There are lots of other

organisations; I will only speak for ours. For us, we can create many

opportunities but we need to be given that chance.[44]

3.35

Perhaps the most serious challenge of all is the perception of gaming of

government contracts rather than companies seriously engaging with how to

genuinely satisfy local Aboriginal employment requirements. Mr David Ross,

Director of the Central Land Council, recounted a story his son told him about

a contractor who proposed forming a 'part-Aboriginal-owned company' to improve

access to work in Aboriginal communities. However, the proposal to form the

company would not have resulted in any real employment opportunities for local

Aboriginal people.[45]

3.36

The government has acknowledged that the money it spends in providing

services to remote communities has the potential to drive employment outcomes

for members of those communities. This potential can only be realised if the

spend is well deployed—by many accounts it is not. The common thread across the

testimony received by the committee was the lack of a structured connection

between government expenditure, and the aims and processes of CDP.

Trauma

3.37

Many witnesses expressed concern about the impact of trauma on an

individual's capacity to be job-ready. Ms Baird described the role that trauma

plays in disempowering individuals and communities from seeking and maintaining

ongoing employment:

The[re] are many underlying causes of joblessness in

Kununurra and the outlying communities. The significance of trauma and family

issues and relational problems cannot be underestimated. For many people, it's

difficult to maintain employment not just because they lack education or skills

but also because they find it difficult to regulate their emotions and

behaviour. Minor issues can often escalate to periods of exclusive behaviour

which limits their employability. The abuse of alcohol and other drugs to help

individuals cope with strong emotions also clearly impacts on their ability to

maintain employment. Greater emphasis needs to be placed on healing underlying

trauma not just on education and training.[46]

3.38

The committee heard about the powerful nature of not just past

experiences of trauma, but the lived experience of people dealing with ongoing

traumatic experiences:

Even just getting out of the door in the morning if you have

experienced family violence the night before can be a huge challenge. There are

so many issues that affect them even getting there in the first place and then

they have to deal with any triggers that might come up during the day.[47]

3.39

The long term effects of trauma are felt by the whole community with

children often experiencing it as a consequence of the trauma experienced by

their own parents:

The trauma that I see is like the kids getting sworn at by

their parents, not being fed and parents having no money to feed them. I get

phone calls from some of my clients asking me to lend them some money because

they've spent all their money on other things. They ring me and ask, 'Can you

lend me $20 till pay day so I can go and buy some sausages and bread and

whatever.' Kids are starving, so that's part of the trauma. They don't go to

school because they don't have clean clothes, they don't have uniforms and they

don't have what it takes to fit in to the schools. It can also affect them

psychologically too; they too can become victims. At our mental health service

we also have a unit there called the children and adolescent unit. We also work

alongside kids affected by trauma and that sort of stuff. It's very traumatic

for most of them.[48]

3.40

Trauma is compounded in remote communities due to the lack of mental

health services. For a while, outreach of mental health services were provided,

but according to Ms Vanessa Thomas of the Mulga Queen community, this has now been

discontinued:

At first we did, but now they don't come anymore. I don't

know why. They tell us that we have to go into Laverton, but, like I said, the

transport. Because AMS [Aboriginal Medical Service]—Bega Garnbirringu—used to

come out there and do stuff but they don't do it any more. They have a mobile

clinic, but they only go as far as Laverton. They said that we have to go into

Laverton but we've got no transport.[49]

3.41

Furthermore, Mr Matthew Ellem, General Manager of Tangentyere Employment,

noted that for many people currently participating in the CDP, the provision of

basic health and other social services is far more pressing than the need for an

employment service.[50]

Cultural and family obligations

3.42

Many witnesses highlighted the fundamental importance of culture and

family responsibilities to Indigenous culture. Ms Ada Hanson of the KBARG summarised

this view:

We want our values, beliefs, culture, language, knowledge and

systems to continue, as these provide meaning for us. They are our identity,

but we want to successfully participate in the cultural interface with regard

to employment opportunities and engagements.[51]

3.43

A struggle exists between the cultural and family responsibilities of Indigenous

people and their obligations under the CDP. One participant described the 'two

different laws' that need to be considered and that both laws are not always

able to be accommodated:

We are living in two worlds. Two different laws. There are

too many rules, we can't keep up. The two different laws, they conflict.

We have other responsibilities at home. We can't do them

because we have to do activities.[52]

3.44

Ms Thomas suggested that the CDP is not as accommodating as the former

CDEP was:

CDEP was good! They worked with us about culture. But this

other one, the CDP, does not work! It penalises the people and there is

poverty.[53]

3.45

Mr Sibosado also stated his view that CDP is not dynamic enough to take

account of people's cultural obligations:

That's the disconnect in all of this program delivery. We

hear about people being breached if they have to attend a funeral. I've been in

that situation, where I've told the employer, 'Well, it's not negotiable. I'm

sorry if you have to sack me, sack me, but I have a cultural obligation to

attend that funeral. If you don't understand that, that's your problem.'[54]

3.46

According to Mr Klerck, the Forrest Review advocated that 'certain

cultural activities happen outside of business hours or during holiday periods under

a section that talks about distractions'.[55]

3.47

In her submission, Dr Kirrily Jordan noted that cultural obligations and

caring responsibilities 'mean that full-time work is not a realistic option'

for many people in remote communities.[56]

Furthermore, even when absences from CDP are approved for cultural reasons,

many people feel that the CDP provider is imposing a personal value judgement

on these cultural activities. This personal judgement is one of the reasons why

some people have disengaged from CDP and become subject to penalties as a

consequence.[57]

3.48

Research from both Canada and Australia has suggested that flexible

employment arrangements that enable Indigenous workers to be involved in

traditional and cultural activities (including seasonal fishing and hunting, funerals

and other cultural obligations) can help improve the engagement and retention

of Indigenous workers, especially in regional and remote locations.[58]

3.49

Ms Carmody spoke about the need to recognise differences between

Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultural expectations:

We have cultural obligations we need to attend to and we have

family obligations. All our obligations are different and they don't sit in the

stereotypes of white people. So we have white people making these policies that

don't take into consideration our obligations in the community. When they

fulfil these obligations, they get penalised, and they get penalised for eight

weeks.[59]

3.50

A 2009 evaluation of CDEP by the Department of Finance also noted the

presence of 'family obligations that flow from collectivist culture' and family

pressures in the communities in which CDEP operates. This cultural pressure to

share income may prevent work benefits accruing to the individual and weaken

the incentives to work.[60]

The evaluation concluded that CDEP was not as well suited to address community

development or economic development issues as these were not the same as labour

market preparation and should be pursued separately.[61]

Reluctance of some businesses to employ Indigenous people or employ locally

3.51

The committee heard that one of the key barriers to employment is the

attitude of some businesses to employing Indigenous people. Ms Carmody noted

that there is usually some type of barrier and that it is usually 'from the

business side of things'. Ms Carmody explained further:

There are simple barriers such as businesses not having the

money for insurance to take on a new employee. Some other feedback that I have

been given—I will not name any businesses; otherwise, I will get into

trouble—is that they do not take underqualified people in their businesses. We

have a great program here—and this is specifically for Kalgoorlie-Boulder—but

the barrier is with the businesses and finding employment at the end of it.

That is what I believe needs to be addressed.[62]

3.52

Ms Carmody also described the 'stigma' that is attached to CDP

participants:

You know what—there is a stigma to CDP. I've seen it happen.

I've had it happen to me before as well. I have not been on CDP before.

However, the reality is that, in a business, say you have two people—a black

person and a white person—and they have exactly the same qualifications and

they have gone through Work for the Dole, which is similar, and then the Wangai

person has gone through CDP. They have done exactly the same programs in

exactly the same amount of time, and training et cetera. I can guarantee you

that that business will employ the white person first. I've seen it. I've had

years of experience in HR and I've seen it.[63]

3.53

Some witnesses told the committee that some of the CDP providers are not

based in communities and will instead send non-local staff to visit remote

communities. Experienced local elders who have previously worked for employment

providers as part of CDEP and RJCP have not been engaged by new providers under

CDP. Ms Thomas commented on the experience in her community:

I used to be a placement consultant for [the provider]. I

used to do three days. They've taken that position away, so they have people

who travel out there. But these are people who we don't understand. They are

Pommy people, or Irish people or whatever. It's hard for them to work with the

Aboriginal people, to understand...the culture.[64]

3.54

A number of witnesses also emphasised the extent to which racism still

permeates many of the institutions and services that provide services to

Indigenous Australians.[65]

For example, the committee were told that many companies in the Kalgoorlie

region do not have Reconciliation Action Plans or cultural awareness training.[66]

The committee also heard that the most recent welcome to country at the annual

Diggers and Dealers conference was apparently met with contempt by some

delegates.[67]

Mr Bokelund expressed his view that this attitude to Indigneous customs is

symbolic of a broader racism in the community when describing the welcome to

country:

Yes, and where they're making their wealth from is Aboriginal

land. Yet the opportunity for someone—and I think just the dignity of [the

individual], who did the welcome: he could have gone on and said, 'I didn't do

it for half an hour.' Everyone says he does it for half an hour, but he's never

done it for half an hour—again, the furphies that were

coming out of it. But again, it's just symbolic of something that is a problem

in our society. I thought, it's the 21st century, and we have racism—the

marginalisation of First Australians. We're still dealing with these issues,

today?[68]

3.55

The committee also heard that it is difficult for Indigenous people to

start new businesses as they do not have ready access to capital themselves or

through family or friends. Mrs Christine Boase, Treasurer of the Laverton

Leonora Cross Cultural Association Inc. observed:

One of the issues that I think is a problem is that most

Aboriginal families don't come from a situation where their family has an asset

base. They don't own a house, they don't have money in the bank and most people

don't have superannuation, so they don't have a situation to be able to set up

a business. They don't have the funds, and getting a loan is really difficult.[69]

Committee view

3.56

This chapter has provided a discussion of the more significant barriers that

establish and perpetuate joblessness in remote communities. Many of these

barriers are long standing and have challenged governments of all political

persuasions for many decades. They include no proper links to accredited

training, no link to government investment and procurement, and inadequate

links to other services—in particular health and education. The committee recognises

that CDP has not created these barriers; however, CDP has not assisted in breaking

them down. It is the committee view that any reforms to CDP must take into

consideration all of these factors if future programs are to succeed. Chapter 6

and 7 of the report will explore in more detail how the factors that contribute

to joblessness in remote communities could be better considered and integrated

as part of a new remote employment program.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page