Chapter 1 - Introduction

Terms of reference

1.1

On 10 February

2005 the Senate, on the motion of Senator the Hon

Peter Cook,

referred the following matters to the Committee for inquiry and report by 23 June 2005:

- the delivery of services and options for treatment for

persons diagnosed with cancer, with particular reference to:

- the efficacy of a multi-disciplinary approach to cancer

treatment,

- the role and desirability of a case manager/case

co-ordinator to assist patients and/or their primary care givers,

- differing

models and best practice for addressing psycho/social factors in patient care,

- differing

models and best practice in delivering services and treatment options to

regional Australia and Indigenous Australians, and

- current barriers to the implementation of best practice

in the above fields; and

- how less conventional and complementary cancer

treatments can be assessed and judged, with particular reference to:

- the extent to which less conventional and complementary

treatments are researched, or are supported by research,

- the efficacy of common but less conventional approaches

either as primary treatments or as adjuvant/complementary therapies, and

- the

legitimate role of the government in the field of less conventional cancer

treatment.

Conduct of the Inquiry

1.2

The inquiry was advertised in The Australian and through the Internet. The Committee wrote to

interested individuals and groups inviting submissions. The Committee received 105

public submissions and 8 confidential submissions from a range of organisations,

individuals and Commonwealth and State departments. Many of the submissions

were from individuals describing their personal cancer journey of being

diagnosed with cancer and the impact it has had on their lives and that of

their families. A list of individuals and organisations who made a public

submission or provided other information that was authorised for publication by

the Committee is at Appendix 1.

1.3

The Committee held public hearings in Perth,

Melbourne, Sydney

and Canberra. In organising its

hearing program, the Committee endeavoured to hear from the major organisations

which made submissions to the inquiry, including all the groups who represent

or support individuals with cancer. A number of these individuals also gave

personal testimonies about living with cancer. The Committee also spoke via

teleconference with individuals from acknowledged best practice hospitals and organisations

in the USA and UK.

A list of witnesses who gave evidence at the public hearings is at Appendix 2.

1.4

Some important issues and questions arose from the

submissions and evidence received by the Committee. Professor

D'Arcy Holman,

Head, School of Population

Health at the University

of Western Australia, was

commissioned to provide a response to these issues. The advice and Briefing

Paper provided by Professor Holman

(Holman report) proved a valuable contribution to the Committee's inquiry.[1]

Background to Inquiry - Cancer in Australia

What is cancer?

1.5

'Cancer' is a broadly used expression. The Holman

report describes cancer as not a single disease but rather it is a diverse

group of diseases characterised by the proliferation and spread of abnormal

cells, which cannot be regulated by normal cellular mechanisms and thus grow in

an uncontrolled manner. These abnormal cells may then invade and destroy

surrounding tissue and spread (metastasise) to distant parts of the body via

the circulatory or lymphatic system. Cancer can develop from most types of

cells, with each cancer having its own pattern of behaviour and metastasis.[2] This description reflects that of the National Service Improvement Framework for

Cancer which notes that 'Cancer is a chronic and complex set of diseases

with different tumour sites. For some cancers, there is considerable knowledge

about their causes and optimal treatment. This varies for other cancers.'[3] These views are succinctly drawn

together by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) which defines

cancer as:

...a diverse group of diseases in which some of the body's cells

become defective, begin to multiply out of control, can invade and damage the

tissue around them, and may also spread (metastasise) to other parts of the

body to cause further damage.[4]

The good news

1.6

Internationally, Australia

compares well with other developed countries in terms of its cancer survival

rates. The AIHW report Cancer in

Australia 2001, shows that Australia's

cancer mortality rate is low when compared with other developed countries. In

addition, over the past ten years, total cancer death rates declined by an

annual average of 1.9 per year.[5] Further

good news is that five-year survival rates for the most common cancers

affecting men (prostate) and women (breast) are now more than 80 per cent.[6] This indicates that cancer survival in Australia

is relatively very good and suggests our health system is performing

comparatively well in the areas of early detection and treatment of cancer.[7] Whilst this is welcome news it is no

excuse for complacency and one of the motivations of this report is to discover

if we can do better. Based on the international evidence provided, it is clear

that cancer treatment is dynamic and evolving with new aspects of medicine

continuing to provide new opportunities.

The increasing burden of cancer in

Australia

1.7

Given these achievements in decreased mortality and

increased survival, why was an inquiry into the delivery of services and

treatment options for persons diagnosed with cancer in Australia

needed? Firstly, cancer currently places a huge burden on the community and

this is set to rise in the coming years. Despite advances, cancer remains a

leading cause of death in Australia

accounting for 28 per cent of all deaths in 2003.[8] Cancer currently accounts for 31 per

cent of male deaths and 26 per cent of female deaths. In 2005 we can expect

that there will be around 36 000 deaths in Australia

due to cancer. Cancer also accounts for an estimated 257 458 potential

years of life lost to the community each year as a result of people dying of

cancer before the age of 75.[9]

1.8

In addition to the existing burden, the cancer

incidence rate has been increasing over the past 10 years. Recent trends in

cancer data produced by the AIHW indicate that the annual number of new cancer

cases diagnosed rose by 36 per cent between 1991 and 2001, compared with

population growth of 12.3 per cent. The AIHW noted that there is likely to be

an increase of similar magnitude over the next 10 years. Currently, one in

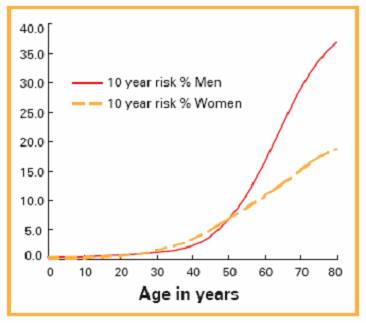

three men and one in four women will be diagnosed with cancer before the age of

75 years (see Figure 1.1).[10] In fact, the

sentiment that 'every Australian is likely to be affected by cancer, either

through personal experience or the diagnosis of a loved one'[11] was typical of that expressed in many

submissions.

Figure 1.1: Risk of being diagnosed with cancer in the

next 10 years

Source:

Cancer in Australia: An update for GPs, Australian Family Physician, v.34, January/February 2005, p.43.

1.9

The increase in the incidence of cancer is partly

explained by Australia's

ageing population as cancer incidence is lowest in late childhood and increases

with age. The most rapidly increasing age group in the population is aged 65

and over and the average age of first diagnosis for cancer is 66 years for

males and 64 years in females.[12]

1.10

Along with increased incidence of cancer we can also

expect detection, treatment and survival rates for cancer to continue to

improve, meaning that there will be more people living with cancer for longer

in the future but with relatively fewer taxpayers to support them. The

Australian Bureau of Statistics notes that 'currently more than 267 000

Australians are living with cancer, many with persistent and incurable forms'.[13] Professor

Holman noted that cancer patients living

longer 'is the single most important reason why so many of us are now in

contact with a relative or friend who is living with cancer'. He provided data

from the WA Data Linkage System which shows that 'in WA the prevalence of

active cancer (ie, people 'living with cancer' that requires ongoing clinical

management) increased from 5.1/1 000 to 7.4/1 000'.[14]

1.11

The growing number of people being diagnosed with

cancer and living with cancer for longer will inevitably increase the demand

for cancer resources and services. AIHW data shows that:

- there was a 31 per cent increase in

inflation-adjusted cancer expenditure from 1993-94 to 2000-01;[15]

- Average cancer expenditure per person was $146

for males and $135 for females in 2000-01. This was much higher in the older

age groups. In the 65-74 year age group, average cancer expenditure per person

was $641 for males and $389 for females while in the 75 years and over age

groups, the averages were $984 for males and $480 for females[16]; and

- New cases diagnosed in 2001 showed an increase

of 22 000 on 1991 figures.[17]

1.12

These trends will place added pressure on the national

health budget and will pose ongoing challenges to the delivery of optimal

cancer care in Australia.

The need to ensure the best use of

cancer resources

1.13

Witnesses from the Australian and State governments informed

the Committee about the cancer initiatives being undertaken to improve

treatment and services. The Committee was concerned about the potential for

uncoordinated systems to emerge and how sharing information on the development

of initiatives between jurisdictions would occur. The Committee considers that

Cancer Australia should have a role to ensure the development of well coordinated

cancer initiatives in the various jurisdictions and provide a forum for

jurisdictions to report progress on their respective initiatives to facilitate

the sharing of information.

1.14

During the course of the inquiry the Committee was

advised that there were more than 100 government and non-government organisations

that contribute to cancer policy or are involved in cancer treatment or support

around Australia

(see Appendix 3). The Committee recognises the valuable role played by these

services, however, given the increasing burden that cancer will place on the

community in the coming years the Committee believes that there is a need to

ensure that cancer resources are well organised, used efficiently and

effectively and that any potential for duplication and overlap is addressed.

1.15

The large number of organisations involved in cancer

policy or support was also raised by some witnesses. Professor

Coates described the functions of various

bodies to the Committee but added:

I do have a PowerPoint presentation which I call 'the alphabet

soup', which goes through some of these myriad acronyms. It contains a diagram,

which looks rather like one that was put up to an ALP conference, of the

spaghetti connections between various bodies in the cancer universe.[18]

1.16

The Committee also noted the large numbers of tumour

specific support groups which, although filling a void for information and

support, may benefit from the promulgation of best practice models. Dr

Hassed spoke to the Committee about evidence

that not all cancer support groups seem to be as effective as every other. He

noted that effective cancer support programs significantly improve the mental,

emotional and social health of participants and are associated with

significantly longer survival.[19]

1.17

The potential for improved organisation of support

services was acknowledged by Mr Davies,

Department of Health and Ageing, who told the Committee that the Department has

commissioned The Cancer Council Australia to undertake a review of the cancer

support networks and also to examine overseas experience. The objective would

be to identify best practice models and promulgate these to be shared among the

organisations.[20]

1.18

The necessity for cost-efficient delivery of cancer

care services was reinforced by Professor

Holman:

...the increasing prevalence of active cancer has profound

implications for the planning, provisions and financing of health services. An

increasing proportion of health care resources will inevitably need to be

allocated to cancer care, and more cost-efficient ways of delivering that care

will become imperative.[21]

Increasing patient focus and empowerment

1.19

People being diagnosed with cancer are demanding more

information about their cancer, their treatment options and the role they can

perform. As Dr Gawler

noted: 'There is huge public interest in how much an individual can affect the

outcome of their illness'.[22] Cancer

patients are becoming more active participants in their treatment and there are

growing demands for:

- Patient-focussed, coordinated multidisciplinary

care to address the current cancer care lottery and provide best practice care

along the care continuum;

- Support throughout the cancer journey;

- Access to evidence-based quality care, including

clinical trials, and a willingness by medical practitioners to discuss

treatment options, including complementary therapies;

- Greater and easier access to understandable and

authoritative information, including complementary therapies, to assist

patients with making informed treatment decisions and to enable dialogue with

health professionals; and

- Equitable access to care for rural and

Indigenous Australians.

Patient-focussed,

coordinated multidisciplinary care to address the current cancer care lottery

and provide best practice care along the care continuum

1.20

This issue has been precisely described by Lance

Armstrong, one of the world's most

recognised athletes who challenged his cancer head-on:

From that moment on, my treatment became a medical

collaboration. Previously, I thought of medicine as something practiced by

individual doctors on individual patients. The doctor was all-knowing and

all-powerful, the patient was helpless. But it was beginning to dawn on me that

there was nothing wrong with seeking a cure from a combination of people and

sources, and that the patient was as important as the doctor.[23]

1.21

Cancer patients spoke to the Committee about the

'cancer lottery' starting at the point of diagnosis where they found the referral

process ad hoc, with many finding specialists through serendipitous connections

and word of mouth. Patients wanted more information to be able to choose a

specialist they felt comfortable with.

One of the critical issues in terms of the health system in Australia

is that it is absolutely fragmented – the left hand does not know what the

right hand is doing.[24]

1.22

Witnesses also reported their care had been fragmented

and disorganised and individual support needs had not been met. The National

Breast Cancer Centre noted:

In Australia,

screening, diagnosis, treatment and supportive care for patients with cancer

are typically provided by different services, often with little coordination,

leading to fragmented care, sub-optimal management and high health care costs.[25]

1.23

Cancer patients wanted greater coordination of care

along the care continuum through a multidisciplinary approach and combined with

better support mechanisms. Cancer patients told the Committee how they

experienced feeling 'lost' in the current cancer treatment system which led to

additional personal distress and many reported stumbling over information which

should have been provided to them or readily available in a range of formats.

Support throughout the

cancer journey

1.24

The impact of being diagnosed with and living with

cancer was graphically described by many witnesses:

Cancer affects every aspect of a person's being if they are

touched by it. It affects the patient, friends and health professionals in

their physical life, their emotional life, their mental life and their

spiritual life.[26]

You are in a constant spin. There is

not one thing in your life that remains the same. It is a complete up-ending. I

had to deal with psychological problems, practical problems.[27]

1.25

The Committee heard that people diagnosed with cancer

want recognition that cancer is not just a physical disease but has an

emotional and practical impact on them, their family and carers and that referral

to support services should be standard practice from the beginning of their

cancer journey. This impact on life was vividly described by one cancer

patient:

A diagnosis of cancer brings with it so many other practical

problems and issues. Life on the home front had to go on. My marriage imploded,

my children struggled to cope with the diagnosis. Coping with this whilst

undergoing chemotherapy was a nightmare, but regular psychotherapy helped me to

keep my head above water. Then there were the medical bills, we have top cover

health insurance with Medibank but the gaps that I had to pay left, right and

centre (especially for the psychotherapy as I soon used up my annual allowance)

meant I could not pay my other bills.[28]

1.26

However, cancer patients told the Committee that access

to support in many cases was not automatic, most stumbled across support groups

and government assistance and most did not obtain the support they needed. One

notable exception was in the case of breast cancer where the amount of

information and support services was recognised and praised. Patients also

wanted assistance to navigate their way through the health and hospital systems

as for some it was their first time dealing with these areas. This aspect was

described by the following witness:

One day John was fit – he was

riding his bicycle and running – and the next day he was in hospital with a

brain tumour. I had never been in a hospital. If someone had given me a

brochure saying what a registrar is and what an intern is, I would have known.

I would have had a much better idea of how the hospital system worked. It would

have been brilliant. I just needed a map of the hospital on the very first day.[29]

Access to

evidence-based quality care, including clinical trials, and a willingness by

medical practitioners to discuss treatment options, including complementary

therapies

1.27

Witnesses were unanimous in their call for treatment to

be patient instead of disease focussed. Evidence indicated that cancer patients

were voting with their feet to find practitioners who were willing to take the

time to discuss treatment options, including the use of complementary therapies,

so that they could make informed treatment choices. The following illustrates

this view:

Our experiences with the 'system' were characterised by...a

complete unwillingness to discuss any potential action other than the medical

treatment being provided by the specialists...[and] a failure to provide any

advice that alternative sources of information existed – beyond the very

limited, and medically oriented handouts from the hospital – and that this

information might not only enhance the treatment, but make it more palatable.[30]

Parents of a cancer

patient described their experience:

We were not given options in respect of treatments. Medical

conventions knew best. We were patronised at every point. No choices. We

accepted that the radiotherapy and chemotherapy as presented was the only way

to go. Our daughter was very keen to do something for herself, although told

there was nothing that she could do.[31]

1.28

The Committee was advised that in comparison to

overseas cancer centres such as Memorial Sloan-Kettering in New

York, the number of cancer patients enrolled in clinical

trials in Australia

is very low and clinical audits are rare.[32]

These issues are discussed further in chapter 5.

Greater and easier

access to understandable and authoritative information, including complementary

therapies, to assist patients with making informed treatment decisions and to

enable dialogue with health professionals

1.29

Australians are becoming better informed about health

issues thanks to greater access to medical and health information on the

Internet and national preventative health campaigns. There is a growing trend for

people wanting to take responsibility for their health and well-being. As a

result, when a disease like cancer is diagnosed, many patients wish to be

active participants in their treatment plans to feel a greater degree of

influence and control. Cancer support organisations in Australia

and overseas support and promote the view that knowledge is power for cancer

patients, as exemplified by the comments of Mr

Ulman from the Lance Armstrong Foundation:

We believe that in your battle with cancer knowledge and

attitude is everything. We really strive to not only inspire but also empower

those people with cancer so that they have the tools and information they need

to live with a very high quality of life.[33]

1.30

Cancer patients are requesting more information in

order to better understand treatment options and to be an active participant in

decision making. Patients wish to engage in a dialogue with their medical

practitioners and are seeking the information to do so. Witnesses told the

Committee that they struggled to find authoritative information and more often

than not just stumbled across information on the Internet and through talking

to people.

I had to constantly ask for information, and I still found out

so much by accident and from other people making a comment.[34]

1.31

This call for greater information has resulted in

publications such as the Directory of

Breast Cancer Treatment and Services for NSW Women produced by the Breast

Cancer Action Group NSW in association with the NSW Breast Cancer Institute.[35] However, the call for more information

from cancer patients is relevant for all stages of the cancer journey.

Equitable access to

care for rural and Indigenous Australians

1.32

The Committee heard evidence of inequalities in the

health system for rural and Indigenous Australians. Mr

Gregory from the National Rural Health

Alliance referred to data that people in country areas who are diagnosed with

cancer are 35 per cent more likely to die within five years than cancer

sufferers in the city. Mr Gregory also provided alarming statistics for

Indigenous Australians where evidence from the Northern Territory and South

Australia shows that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders with cancer are

twice as likely to die from the disease as non-Indigenous people with the

disease.[36]

The Call

for Reform of Cancer Care in Australia

Cancer services in Australia

are in what are probably the early stages of a major paradigm shift. I think

this shift in the approach to treating cancer has been fuelled primarily by the

interest of the public and by their interest in the better outcomes that have been

achieved in recent years. It is supported by a great deal of research...it is

also being driven by progressive universities providing more graduate training

and postgraduate training...and it is starting to show up in progressive

hospitals.[37]

1.33

The consumer needs outlined above have been recognised

and a number of recent reviews and publications by consumers, practitioners and

cancer care providers have recommended the reform of cancer care in Australia.

They acknowledge that some improvements are occurring but suggest that cancer

care is now at a crossroads and that the next step to improve cancer treatment

and services in Australia is the development of a national, evidence-driven

approach, involving greater coordination of the cancer patient's journey and

recognising the need for a consumer-focussed approach to cancer care.

1.34

These publications include: Optimising Cancer Care in Australia,

produced by the Clinical Oncological Society of Australia, The Cancer Council

Australia and the National Cancer Control Initiative. The key issue highlighted

in the report is the failure of the health system to provide integrated cancer

care.[38] Other reports, Priorities for Action in Cancer Control

2001-2003 and the National Cancer

Prevention Policy 2004-06, have identified priorities for new developments

in cancer control and made recommendations on how Australia

can enhance its achievements in cancer prevention. National Breast Cancer

Centre publications, the Report of the

Radiation Oncology Inquiry, A Vision for Radiotherapy 2002 (the Baume Inquiry)

as well as Cancer Council Reports and consumer forums have also called for

reforms to the funding, operation and integration of cancer services.

1.35

Key aspects of the recommendations in these reports are

that cancer care should focus on the patient not just the disease and that

emotional and practical support should be included as standard components of

care. They highlight the differences in the public and private systems and also

identify inequalities in the system where cancer outcomes and services for

regional and rural patients and particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islanders are far from optimal and must be improved.

Conclusion

1.36

Australia

can feel justifiably proud of its internationally recognised achievements in

the areas of decreased mortality and increased survival for people with cancer.

However, the increasing numbers of people being diagnosed with cancer and

living longer with cancer will present further challenges to the delivery of

optimal cancer care services in Australia. The increasing number of people

being diagnosed with cancer will mean that there will be a need to ensure that

resources for cancer treatment and support are organised efficiently and are

directed to areas of most need to improve outcomes.

1.37

These future consumer needs are being recognised by

cancer organisations, practitioners and care providers. Recent reports have

called for reform of cancer care in Australia

to develop a national, evidence-driven approach, involving greater coordination

of the cancer patient's journey and recognising the need for a

consumer-focussed approach to cancer care.

1.38

Based on the submissions and evidence presented during

the inquiry the Committee was pleased to note that the areas of consumer need

have been recognised by the Federal and most State and Territory Governments.

Early steps are being taken to address the calls for reform with a focus on

building national service frameworks at the Commonwealth level and

implementation strategies at the State and Territory level, though some

jurisdictions are more advanced than others. The different role and responsibilities

of the Commonwealth and the States and Territories and the strategic framework

that has been developed for the delivery of cancer treatment and services are

discussed in chapter 2.

1.39

However, despite some achievements and advances in

treatment, there remain inequalities and serious gaps in the system and not all

Australians have access to best practice cancer care. This is true even in some

outer metropolitan areas but particularly for rural and Indigenous Australians.

Achieving improved equality in cancer treatment and services for rural and

Indigenous Australians is a key challenge for the health system and is

discussed in chapter 3.

1.40

The gaps in the system include lack of data relating to

the incidence and treatment of Indigenous Australians; a poor record of

clinical audit, especially in the private sector, including poorly organised

hospital based cancer registries (in both public and private settings); poor

access to psychosocial support and systemic rejection by conventional health

professionals of complementary therapies or integrative medicine.

1.41

People diagnosed with cancer are becoming more active

participants in their cancer treatment and are demanding greater coordination

of care through multidisciplinary teams, access to authoritative information to

assist them in making treatment decisions, assistance to navigate their way

through the health care system and more emotional and practical support for

them and their families and carers. These issues are discussed in more detail in

chapter 3.

1.42

The Committee also heard evidence from hospitals,

organisations and support groups who are challenging themselves to meet the

needs of cancer patients using more innovative models of care, sometimes

despite the health system surrounding them. These successful models, as well as

the barriers to their further implementation, are also discussed in chapter 3.

1.43

The trend towards taking more responsibility for one's

health is also evident in the increased use of complementary medicines and

therapies. Chapter 4 discusses the issues of efficacy and safety and moving

towards integrating the best of mainstream treatments with evidence-based

complementary therapies. Integrative medicine and the use of complementary

therapies as practiced overseas at leading cancer institutions and in Australia

are also discussed in chapter 4.

1.44

The Committee acknowledges that improving cancer

outcomes is a multifactorial field that extends far beyond the scope of this

inquiry. While the Committee's investigations were necessarily focussed by the

terms of reference, other specific issues relating to cancer treatment and care

including early detection through screening, the special needs of adolescents, research

and clinical trials, data collection and palliative care were also raised

during the inquiry. These issues are considered in chapter 5.

1.45

The important aspects of cancer prevention or risk

reduction, including ongoing public health programs addressing issues such as

tobacco control, skin cancer and diet, were not part of this Inquiry but recognised

by the Committee as highly relevant to Australia's

health system.

Acknowledgments

1.46

The Committee is grateful for the many submissions

received from institutions, professional associations, government and

non-government organisations, support groups and particularly individuals. The

patients, families and carers provided the Inquiry with extremely valuable

information in submissions and at the hearings which enabled the Committee to

better understand a patient's cancer journey and where improvements could be

made.

1.47

The Committee recognised that cancer treatment and care

is an area where there is enormous goodwill, outstanding dedication and where

everyone involved is working towards the same goal to improve the cancer

journey, eliminate the cancer lottery and achieve the best possible outcomes

for cancer patients.

1.48

The Committee acknowledges the work already undertaken

in the government and non-government sectors to develop strategic direction and

a national framework for cancer care in Australia.

The significant work and consultation undertaken to produce documents such as Optimising Cancer Care and the National Service Improvement Framework for

Cancer has meant that the existing cancer care system has been the subject

of recent review and that many areas for improvement have been identified and

remedial action recommended. It is timely that these reports and plans for

action be built upon by the Committee's report.

1.49

The timeframe for the Committee to inquire and report upon

this very important subject was especially tight and the Committee acknowledges

the assistance received from many individuals and organisations, but

particularly from Mr Clive

Deverall. The Committee

also expresses its thanks to Professor D'Arcy

Holman and Rachael

Moorin, School

of Population Health at the University

of Western Australia, for their

detailed response to issues and Briefing Paper that provided a valuable

contribution to the Committee's deliberations.

Barb's story -

Informing choice in her cancer journey

In the last days of December 1988, at the age

of 30, I was taken to hospital with a very painful and bloated stomach and a

fever that my GP could not get under control. The day after some exploratory

surgery I was told by a young intern doing his ward rounds that I would need

further treatment - chemotherapy or radiotherapy. That was the first

information I was given post surgery. The doctor delivered the news, pulled the

curtain back around my bed and disappeared on his rounds again. I was in shock.

At no stage during my stay at the hospital or, indeed, afterwards was I offered

any kind of counselling or given any acknowledgment that I might be upset or

need help. I was diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the peritoneal cavity...My

surgeon and, subsequently, the initial oncologist I consulted told me that I

had better do everything I wanted to do before next Christmas and that there

was no treatment to be had that would help me. Wanting another opinion, I

consulted another oncologist a few weeks later. This one told me that probably

nothing would work but, if I liked, he could try some extremely aggressive

chemotherapy that would make me very sick and that anything else I tried to do

for myself - in particular, any changes I made to my diet - would be useless

and a waste of time...

I had found a copy of Ian Gawler’s book, You Can Conquer Cancer, and had read most of it. Everything he

said in there made sense to me and, besides, I obviously had nothing to lose by

taking on an approach in which I took an active and positive role in the

recovery I hoped to make. I did not dismiss what the doctors had to say; I used

it as a starting point and did heaps of research on my cancer and the exact

types of chemotherapy drug treatments that had been tried in the past. I found

yet another oncologist who was prepared to try the slightly unorthodox chemo

that I had uncovered in my research... My doctor was sceptical but, with no other

real options, he decided there was nothing to lose and he got on with it...I also

enrolled in the Gawler Foundation’s 10-day course at the Yarra Valley Living

Centre. What I learned and how deeply I changed during those 10 days changed

not only the length of my life - I am totally convinced of that - but also the

quality of my life. In particular, I realised that there were things that I

could do that could change not only the course of the disease but the quality

of the journey along the way...

After the course, I had tonnes of information

- and I knew how to go about finding tonnes more - about how to maximise my

chances of healing through eating well. Although one of the first doctors I saw

told me that fresh juices were a waste of time and that all that would happen

was that my skin would turn orange from the carrots, which it did a bit, it

just made total sense to me that every nutrient or toxin I put into my body

would have some influence on my immune system and my outcome. I also grew to

love and value my time out while meditating. Again, I am absolutely certain

that it influenced my outcome.

Committee

Hansard 18.4.05, pp.55-6 (Ms

Barb Glaser).

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page