|

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page

CHAPTER 6

The assessment process

Introduction

6.1

Determining the outcome of claims for refugee status entails two

separate but related assessment processes. The first, conducted by the Department

of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC), determines whether claimants are genuine

refugees in need of protection. The second process is a security assessment

conducted by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO).

6.2

This second process begins only if and once a person is assessed as

being a refugee in need of protection. Those found not to be refugees are

subject to deportation, and are not assessed further unless they appeal the

initial negative assessment. These people are referred to as being on 'negative

pathways'. On 29 June 2011, there were over 2500 people on negative pathways in

detention.[489]

6.3

Once refugees are security assessed, they are either released into the

community, or, if they receive adverse ASIO assessments, they are kept in

detention, indefinitely.

6.4

At present, the majority of asylum seekers remain in detention for the

duration of these processes. The average time spent in detention is 297 days.[490]

Most people who seek asylum in Australia are ultimately found to be refugees

and issued protection visas.[491]

6.5

The first part of this chapter will outline the two assessment processes

asylum seekers undergo. In the second part the Committee will focus on the

length and consequences of this process.

Legal framework

6.6

The United Nations 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees

(the Refugee Convention) defines who is a refugee, their rights and the

obligations—both legal and moral—of states. Until the 1967 Protocol, the

Refugee Convention applied only to post-World War II European refugee

situations. These limitations were removed by the 1967 Protocol to allow

the Refugee Convention to apply to refugees in any country. Together, the 1967

Protocol and Refugee Convention form the cornerstones of refugee protection

worldwide.[492]

6.7

People from anywhere in the world, whether Irregular Maritime Arrivals

(IMAs) or not, have a legal right to make claims for asylum in countries which

have signed up to the abovementioned treaties, irrespective of their method of

arrival. As a signatory to the abovementioned treaties, Australia has a legal

obligation to assess all claims for asylum against criteria defined at Article

1A of the Refugee Convention.[493]

6.8

The visa process for determining who comes into Australia is regulated

under the Migration Act 1958 (the Act). The Act was amended by the Migration

Amendment (Excision from Migration Zone) Act 2001, which barred

non-citizens who first entered Australia at an excised offshore place without a

valid visa from applying for such a visa during their stay in the country.

Assessing protection claims

6.9

Depending on people's mode of arrival, there are currently two different

avenues of assessment of protection claims, dependent on asylum seekers' place

of arrival. Those who enter Australia's migration zone who are not

offshore entry persons (OEPs) can immediately apply for a protection visa

(Class XA)(Subclass 866).[494]

6.10

However, OEPs arriving at an excised offshore place cannot lodge

applications for a protection visa. Under the Protection Obligation

Determination (POD) process, which applies to OEPs, the Migration Act prevents

a person who arrives at an excised offshore place and is not in possession of a

valid visa making an application for a visa. Any protection claims made since

the introduction of the POD process are subject to the process.[495]

6.11

OEPs are sent to Christmas Island, where they begin their separate

assessment process.[496]

Protection visa assessments for

non-OEPs

6.12

Since 2005, DIAC has been required to reach protection visa decisions

within 90 days of receipt of an application. Approximately 60 per cent of such

decisions were made within the required timeframe in 2010-11. Where this 90-day

requirement is not satisfied DIAC reports this to the Minister and these

reports are tabled in Parliament.[497]

6.13

The application process begins when a person applies for a protection

visa. As soon as they provide personal identifiers, their application is

accepted and their eligibility for a bridging visa assessed:

Asylum seekers who have arrived in Australia’s migration zone

and who subsequently lodged a Protection visa application may receive a

bridging visa. In most cases, the bridging visa allows applicants to remain lawfully

in Australia while their Protection visa application is being finalised.

Consequently, most Protection visa applicants are not detained for long

periods, and they often live in the community while their application for

protection is being assessed or reviewed.[498]

6.14

At this point applicants undergo health, identity and character checks.

A DIAC officer assesses the case and determines whether further information is

required from the applicant. The applicant is then invited to an interview with

their allocated decision-maker. If more information is required from the applicant,

it may be requested during the interview or at any other point of the

assessment process.

6.15

On the basis of the information provided, the relevant DIAC officer

makes a decision to grant or refuse a protection visa. The applicant is then

informed of this decision and their right to review in the case of a refusal.

6.16

Asylum seekers who are found to be refugees are offered permanent

protection in Australia, subject to appropriate health screening, meeting the

character requirement and passing security checks.[499]

6.17

Applicants not granted a protection visa may seek a review with the

Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) with the power to review protection visa

applications. This power is subject to the Minister's decision that a review or

change in decision would be contrary to the national interest.

6.18

This review process is explained later in this chapter.

Protection determination process

for OEPs

6.19

OEPs are prevented by the Migration Act from making a valid application

for a protection visa. If they raise a protection claim, it is subject to the

POD process.

6.20

The POD process represents a recent change in the department's

assessment processes. It was introduced on 1 March 2011, replacing the previous

Refugee Status Determination (RSD) process after a High Court decision on 11 November

2010 which found that Irregular Maritime Arrivals (IMAs) should be afforded

natural justice and provided access to judicial review.

6.21

Irrespective of their date of arrival, IMAs who received a primary

assessment interview after 1 March 2011 are now processed under the POD

process.[500]

Claims for protection subject to the POD process are assessed on an individual

basis against the criteria at Article 1A of the Refugee Convention, and in

accordance with Australian legislation, case law and up-to-date information on

conditions in the applicant's country of origin.

6.22

Applicants must put their claims in writing. All applicants are invited

to an interview to discuss their claims and provide more information if

required. Procedural fairness applies to all applicants in responding to

information that may affect the outcome of their assessment.[501]

6.23

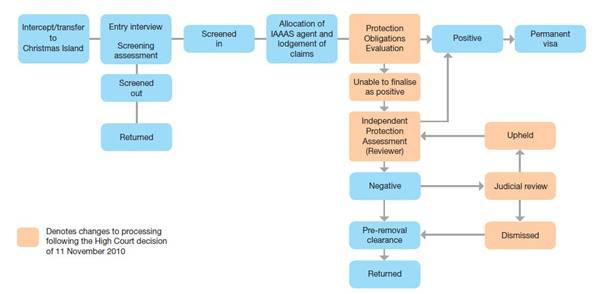

The following diagram provided by DIAC outlines the POD process:

Source: DIAC

6.24

The POD process is non-statutory and has two parts: a Protection

Obligations Evaluation (POE) stage and, in the event of a negative decision at

this stage, an Independent Protection Assessment.

Protection Obligations Evaluation

(POE)

6.25

The POE determines whether an IMA is owed protection under the Refugee

Convention. To determine this, claims are assessed against criteria set out by

the Refugee Convention and considered in accordance with case law. Assessors

draw on currently available country information. For reasons of procedural

fairness, IMAs have the opportunity to comment on the information being

considered if they believe it could be adverse to their case, and can update

country information if there is a change in conditions in their country of

origin.[502]

6.26

To make a POE decision, the Department draws on a range of sources,

including:

-

the Department's Country Research Service, which collects

information from a variety of sources, such as international human rights

groups, Australian posts overseas, foreign governments, academics,

international media and other organisations;

-

departmental guidelines and advice on refugee law, protection

policy and procedures; and

-

client statements, which may include supporting material and

additional comments. These are provided in writing or during an interview, with

the help of an interpreter if necessary.[503]

6.27

If the POE finds that an IMA is owed protection, the appropriate

recommendation is made to the Minister, who then exercises their power to lift

the bar, allowing the IMA to apply for a protection visa.

6.28

It is important to note that people who arrived as IMAs and received

their primary assessment before the POD process came into being on 1 March 2011

continue to be processed under the old Refugee Status Assessment (RSA) and the

Independent Merits Review (IMR) processes.

6.29

Those processed under the new POD process do not themselves have to lodge

applications for decisions to be reviewed. Instead, if DIAC is not satisfied

that a person is a refugee, their case is automatically referred for an

independent protection assessment.[504]

Opportunity for review

6.30

Australia's immigration detention population currently consists mostly

of those who have received a negative protection visa decision and are involved

in process of review.[505]

Several avenues exist to enable these asylum seekers and/or DIAC to review

negative decisions.

Refugee Review Tribunal

6.31

Non-OEPs whose applications for protection visas are refused are able to

apply to the RRT for an IMR in relation to their case. Alternatively, they may

apply to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal if their application was rejected

for character reasons.[506]

6.32

The RRT is an independent statutory body which '...provides a

non-adversarial setting in which to hear evidence'. It has the power to review

protection visa application decisions – unless the Minister is of the view that

such a review would be against the national interest. Applicants' claims are

examined by the tribunal against the provisions of the Refugee Convention.[507]

The RRT may:

-

uphold the primary decision—agreeing that the applicant is not entitled

to a Protection visa

-

vary the primary decision

-

refer the matter to the department for reconsideration—the

department then makes a fresh assessment of the application, considering the

RRT’s directions and recommendations

-

set aside the department’s decision and substitute a new decision—if

the RRT finds the applicant is entitled to a Protection visa.[508]

6.33

When undertaking its reviews, the RRT considers the merits of each

protection visa application anew, taking into account any relevant new

information, such as information supplied by the applicant or changes in

country information.[509]

Independent Protection Assessment

6.34

When a person who arrived offshore receives a negative decision at the

POE stage, their case moves into the second part of the POD process, the

Independent Protection Assessment phase. At this stage an independent assessor

considers the case and its supporting information. The assessor may also

interview the refugee claimant before making a recommendation about whether or

not they should be found to be a refugee. The number of assessors was increased

to 124 in June/July 2011, and a Principal Reviewer and 3 Senior Reviewers

appointed to strengthen professional supervision.[510]

6.35

In November 2010 the High Court found that people processed under

arrangements applying to OEPs were being denied procedural fairness in the

review of their claim. Following this decision, IMAs who are the subject of a

negative Independent Protection Assessment are able to seek judicial review of

their assessment. The review considers whether legal errors were made

over the course of the decision-making process, but does not reconsider IMA

claims. When judicial reviews find that legal errors have been made, the

original Independent Protection Assessment decision is set aside and a new

assessment made.[511]

6.36

Liberty Victoria acknowledged this important outcome for asylum seekers

arriving by sea, but drew the Committee's attention to the potential for this

to increase time spent in detention:

It is inevitable that applications for judicial review, and

the time taken to finalise these, will add to the time spent in detention by

unsuccessful applicants for asylum (DIAC estimates it will add ‘many months’ to

time spent in detention).[512]

6.37

Non-OEPs whose applications for a protection visa have been refused

already had the right to appeal to a court for review.

6.38

Seeking judicial review concurrently triggers an International Treaties

Obligations Assessment.

International Treaties Obligations

Assessment

6.39

A person who is not found to engage protection obligations may under the

provisions of the Migration Act be subject to removal from Australia.

The removal process:

...takes into account Australia’s non-refoulement (non-return)

obligations under other international human rights instruments, other than the Refugee

Convention, such as the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or

Degrading Treatment or Punishment, the International Covenant on Civil and

Political Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The removal

process also takes into account other unique or exceptional circumstances that

may warrant referral of a person’s case to the minister under section 195A of

the Migration Act.[513]

6.40

For this reason, judicial reviews of negative protection decisions also

trigger an International Treaties Obligations Assessment, which takes into

consideration Australia's non-refoulement obligations in cases where a

person is facing removal from the country. If appropriate, the assessment

results in protection being extended to people who are not found to be refugees

but who may not be returned to their country of origin due to a risk of

torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, punishment or violation of

their right to life, as well as in other exceptional circumstances.[514]

Criticisms of the assessment process and its length

Processing times

6.41

At the outset of this inquiry the Committee sought to establish why so

many people were spending significant periods of time in detention, prolonged

detention being the underlying cause of so much distress, mental illness and

community concern. Despite fluctuations, the Committee is concerned that

overall processing times remain too long, and because the longstanding

government policy has been to detain people for the duration of their

processing, longer processing times translate directly to longer periods in

detention.[515]

On this point, Liberty Victoria submitted that:

The primary reason for such lengthy periods of detention is

the time taken to process the protection claims (and subsequent appeals and

reviews) of people arriving by sea. Such people are dealt with according to the

‘non-statutory’ refugee assessment process. Under the refugee status assessment

and independent merits review process, applicants can expect to wait 12 months

from arrival to finalisation of merits review. Most people are detained

throughout the processing of their application for asylum and subsequent

appeals and reviews.[516]

6.42

The Committee understands that DIAC, together with ASIO, has implemented

a number of strategies aimed at improving the process, which should result in

shorter processing times and better mental health outcomes for detainees. In

its submission the department points to this refined process and cites improved

processing times in 2011:

The department has significantly reviewed its determination

process as a result of the November 2010 High Court decision. This included

introducing the POD process in March 2011, which resulted in a faster initial assessment

of claims and a more efficient referral process for negatively assessed

clients.

Early provision of the latest country information to

migration agents, along with client entry interviews, has assisted agents to

prepare more comprehensive statements of claims at the primary stage.

A significant number of IMA cases were resolved in the

2010-11 program year. In total, 2816 people were released from immigration

detention. Of these, 2738 people were granted Protection visas and 78 were voluntarily

removed from Australia.

The department also has a process known as a Pre-Review

Examination, which was implemented from 22 August 2011 and involves checking if

original decisions on refugee status of IMAs waiting for independent merits

review are still valid and current.[517]

6.43

The department also noted that streamlined security checking was helping

to speed up processing times:

In January 2011 the Australian Security Intelligence

Organisation (ASIO) developed an intelligence-led and risk-managed security

assessment framework for IMAs who meet Article 1A of the Refugee Convention. Since

December 2010 only IMAs found to meet Article 1A of the Refugee Convention are

referred to ASIO for security assessment.[518]

6.44

This new framework was implemented in March 2011 and enabled ASIO to

prioritise long-standing cases. Around 3000 IMAs found to be refugees were

security assessed under the new framework between mid-March 2011 and 8 August

2011.[519]

This ASIO security assessment process is discussed later in this chapter.

6.45

Liberty Victoria was not of the view that DIAC's new POD process

represented a significant improvement:

The Department of Immigration and Citizenship...was required

to overhaul its non-statutory process following the High Court’s decision in

M61 v Commonwealth. It has now announced the new ‘protection obligation

evaluation’ process, which commenced in March 2011. It is beyond the scope of

this submission to comment at length on the nature of this process, its

fairness and its similarities with the ‘refugee status assessment’. However,

Liberty notes that the only substantial difference between the new and old procedures

appears to be that, now, unfavourable assessments will be automatically

referred to independent review. It seems likely this will result in only a modest

improvement to the speed of the process.[520]

Processing suspension

6.46

On 9 April 2010 the Minister for Immigration, Minister for Foreign

Affairs and Minister for Home Affairs announced that the government would not

be processing new asylum claims by Sri Lankan nationals for three months or

those from Afghan nationals for six months.[521]

The policy intention was to ensure that decision-making was based on

up-to-date, accurate realistic information about the country circumstances in

those two places.[522]

6.47

The suspensions were not extended. The government lifted the suspension

for Sri Lankan asylum seekers on 6 July 2010 and for Afghan asylum seekers on

30 September 2010.[523]

6.48

However, over the course of the suspension the number of asylum seekers,

specifically those from Afghanistan, increased significantly. The processing

freeze also resulted in longer periods of detention for existing detainees.[524]

Identifying asylum seekers

6.49

In cases where IMAs are found to be owed protection, those who arrive

with inadequate identification documents may experience added delays due to

concerns about the integrity of their claims. Lack of documentation can also

impede the issuing of travel documents for those subject to deportation, which

in turn increases the time they spend in detention.[525]

6.50

When the Committee pursued the issue of inadequate documentation, it was

reassured that the majority of asylum seekers are in a position to provide

adequate identification within two to four weeks of arrival.[526]

Quality of information used in

assessment

6.51

Country Guidance Notes (CGNs) were introduced by DIAC in 2010 as part of

a range of measures designed to help case officers assess asylum seeker claims:

The CGNs are designed to support robust, transparent and

defensible decision making, regardless of the outcome. The CGNs draw on many

sources including reports by government and non-government organisations, media

outlets and academics. Before they are released, the CGNs are circulated for

comment to key stakeholders including other government agencies such as the

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Attorney-General’s Department,

as well as nongovernment organisations specialising in asylum and protection

issues.[527]

6.52

CGNs assist refugee case officers to:

-

locate and synthesise country of origin information relevant to

assessing claims presented by asylum seekers to Australia

-

identify relevant issues for consideration

-

conduct robust and transparent analysis of claims.[528]

6.53

Guidance notes currently exist for Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq and Sri

Lanka. All CGNs are updated as required and are available on the DIAC website.[529]

6.54

As well as CGNs, refugee case officers routinely use DIAC's country

information database (CISNET) when making their assessments. The database

includes but is not limited to information that is already in the public

domain. Specific documents available on CISNET can be assessed by external

stakeholders under Freedom of Information legislation.[530]

6.55

The quality of RSA and IMR decision-making processes has attracted

considerable criticism from a number of quarters. For example:

RSA and IMR decisions are often sloppy and riddled with

errors, such as text from one decision being copied and pasted into another

decision without changing relevant details such as names, dates and places.

It is imperative that a system of quality control be

implemented to oversee the RSA and IMR decision-making processes. At present,

the process is inconsistent and arbitrary, and unduly subject to the personal

whims and fancies of the individual reviewer. This should not be so.[531]

6.56

Furthermore, the Committee is aware that detainees have questioned the

accuracy of country information used to inform decision-making, asserting that the

information could be prolonging and even skewing the process as a result.[532]

6.57

In a recent ruling, the Federal Magistrates Court of Australia found

that a particular DIAC reviewer appeared to be biased, taking an 'inflexible

and mechanical' approach when reviewing refugee claims by Afghan ethnic Hazara

minorities. The court found that the reviewer did not afford procedural

fairness, in particular:

-

The reviewer used a repeated formula or template for his

recommendation;

-

The formula or template was applied inflexibly by the reviewer

in relation to this review of the applicant's claims and the claims of several

other IMR applicants;

-

The IMR reviewer had used the same formula or template as a

precedent for recommendations in relation to other IMR applications prior to

the applicant's IMR's advisor's submissions.[533]

Committee view

6.58

The Committee notes the differences in assessment processes for onshore

and offshore arrivals seeking asylum, and draws attention to the view of the

UNHCR:

UNHCR is of the view that the offshore procedures for

assessing refugee status should be as closely aligned as possible with onshore

procedures and subject to appropriate legal frameworks and accountability, and

due process. The current policy creates a bifurcated system whereby those

arriving by air receive greater procedural safeguards than those arriving by

sea. It is arguable that this is a discriminatory policy that is also at

variance with Australia’s obligations under Article 31(1) of the 1951

Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, which provides that:

The Contracting States shall not impose penalties, on

account of their illegal entry or presence on refugees who, coming directly

from a territory where their life or freedom was threatened in the sense of

article I, enter or are present in their territory without authorization, provided

they present themselves without delay to the authorities and show good cause

for their illegal entry or presence.

6.59

The Committee believes that Australia's assessment processes should be

consistent with our obligations under the convention. To this end, the Committee

notes recent changes allowing DIAC to use existing powers more flexibly in

assessing IMA asylum seekers, notably by approving them for bridging visas.[534]

6.60

Furthermore, the Committee notes concerns raised by organisations such

as Liberty Victoria about the pre-POD assessment process, the RSA, and the

associated IMR. The Committee is concerned that a significant number of people

in detention are still subject to old processes, simply because they arrived

prior to the new, improved POD process being implemented. The Committee is

troubled by allegations of inconsistency in assessment, and is of the view that

an enhanced quality control system would have the dual benefit of ensuring

probity and easing stakeholder concerns.

Recommendation 25

6.61

The Committee recommends that the Department of Immigration and

Citizenship consider revising and enhancing its system of quality control to

oversee those Refugee Status Assessment and Internal Merits Review processes

still underway.

Security assessments

6.62

Responsibility for determining entry of non-citizens to Australia rests

with DIAC,[535]

and DIAC decides whether and when to refer a person applying for a visa to ASIO

for security assessment. The timing of ASIO security assessments of IMAs and of

onshore arrivals seeking protection visas is not mandated by legislation; it is

a matter of government policy.[536]

6.63

ASIO informed the Committee that its function in this regard is to 'support

the department of immigration [DIAC] in its management of irregular maritime

arrivals.'[537]

ASIO's role and responsibilities are mandated by the Australian Security

Intelligence Organisation Act 1979 (the ASIO Act):

The ASIO Act specifies ASIO's remit as 'security', which it

defines as the protection: of Australia and Australians from espionage,

sabotage, politically motivated violence, promotion of communal violence,

attacks on Australia's defence systems, and foreign interference; and of

Australia's territorial and border integrity from serious threats.[538]

6.64

Individuals are assessed against security threats set out in Section 4

of the ASIO Act:

That includes espionage, sabotage, threats to our defence

systems, promotion of communal violence, and protection of border integrity is

the last one. Here, the particularly relevant one is an issue of politically

motivated violence, which, of course, contains within it the whole question of

terrorism.[539]

6.65

Following a security assessment, ASIO may provide one of three findings:

(a)

non-prejudicial finding, which means there are no security concerns that

ASIO wishes to advise;

(b)

a qualified assessment, which means that ASIO has identified information

relevant to security, but is not making a recommendation in relation to the

prescribed administrative action; or

(c)

an adverse assessment in which ASIO recommends that a prescribed

administrative action be taken (cancellation of a passport, for example), or

not taken (not issuing access to a security controlled area, for example).[540]

6.66

Security assessments are made without regard to social or family

circumstances of the individual being assessed so as to retain objectivity and

ensure that people are assessed exclusively in terms of the potential security

threat they pose. Similarly, character tests are not applied at the time of

assessment:

Security assessments are not character checks and character

factors such as criminal history, dishonesty or deceit are only relevant if

they have a bearing on security considerations. Character is not itself

sufficient grounds for ASIO to make an adverse security finding. Assessments of

character not relevant to security are required to be made by DIAC.[541]

6.67

ASIO only conducts security assessments of asylum seekers able to apply

for protection visas. In the three years 2008-09, 2009-10, 2010-11, ASIO did

not issue a single adverse assessment for onshore arrivals seeking

protection visas. From January 2010 to November 2011, 54 adverse assessments

were issued for offshore arrivals.[542]

Streamlining the assessment process

6.68

Prior to December 2010, it was government policy that every IMA would be

subject to a full security assessment upon arrival. This meant that IMAs were

subject to 'parallel processing', that is, both protection determination and

security assessments conducted upon arrival:

Under this policy, ASIO's resources were expended providing

assessments for a large number of individuals who did not require security

assessment because they were not ultimately assessed to be genuine refugees.[543]

6.69

That is no longer the case. Following an internal review by ASIO of its

assessment processes in 2010, ASIO implemented changes to '...ensure an

intelligence-led and risk-managed approach to security assessments and security

assessment referral.' To this end, in December 2010 the government decided to abandon

parallel processing:

As part of these changes, the Government agreed in December

2010 that only those IMAs who were assessed to be genuine refuges (known as '1A

met' [having met the definition of a refugee under Section 1A of the Refugee

Convention]) would be referred to ASIO for security assessment.[544]

6.70

More about the genesis of the new framework was explained by ASIO

Director-General David Irvine in this way:

This referral process has been developed in consultation with

DIAC. What it has done, particularly recently, is enable us to streamline

security checking for what I will call non-complex cases and that it is

commensurate with the level of risk that they present. What it does is allow us

to focus our most intensive security investigation effort into the groups or

individuals of most security concern. The result is, I believe, particularly in

recent times, that our security checking has become more thorough and more

effective. In fact, this is evidenced in the number of adverse security

assessments, which have increased as a result of our ability to focus on these

complex cases.[545]

6.71

Separately, ASIO reported improvements as a result of the new framework:

The impact of these measures has been a significant reduction

in the number of IMAs in detention solely awaiting security assessment.[546]

How the triaging process works

6.72

When asylum seekers arrive, they are processed by DIAC. Once DIAC

determines that a person qualifies for refugee status, they are measured

against the triaging process. The triaging process is designed to establish,

implement and apply security criteria in order to identify which refugees DIAC

should refer to ASIO for security assessment.

6.73

The Committee was told by Mr Irvine that the 80 to 85 per cent of

refugees who are measured against the triaging process then go through required

immigration processes and to a recommendation to the Minister. The 15 to 20 per

cent of refugees that DIAC refers to ASIO go through a more rigorous security

assessment, and, '...if they are found to be non-prejudicial they go back

through the ordinary way.'[547]

6.74

Mr Irvine gave an example of this process in operation:

Let us suppose that 116 people arrive. Immigration collects

information about those people relative to their claims, their names, their

personal details and so forth. That is then measured against what we would

regard as indicators for concern, and about 80 per cent to 90 per cent of

people would not trigger those indicators of concern. Then they would then go

on and be processed in the normal way to a decision by the minister that they

be given protected visas. Those people who do trigger concerns—and they might

be, say, 15 per cent or whatever of that 116—are then subject to a more

thoroughgoing ASIO investigation in which we have access to all of the

information that they have provided during the immigration process relative to

their claims, and details about them, and that then forms the basis for our

investigation. Out of that comes one of three results. The first is a

non-prejudicial finding whereby we simply advise the department of immigration

that we have no concerns about that person. The second is that we could issue

what I will call qualified security assessments—and we have issued a number of

these—where we identify that there are some security issues but we do not think

they represents such a risk to security that a visa should not be issued. The

third is where we have identified security issues and assess that person for

whatever security reason to represent a threat to security such that a visa

should not be issued.[548]

Process for in-depth security

assessments

6.75

ASIO only conducts in-depth security assessments when refugees are

referred for such assessments by DIAC, 'unless something comes to light where

we discover that, for whatever reason, we need to look at something.'[549]

6.76

However, although DIAC refers individuals to ASIO for such assessments,

the criteria for referral are set by ASIO. Asked whether DIAC determines what

goes to ASIO for assessment, DIAC Secretary Andrew Metcalfe told the Committee,

'ASIO determines what goes to ASIO.'[550]

6.77

In August 2011 Mr Metcalfe gave evidence regarding the application of

ASIO guidelines for referral:

...ASIO has advised us on what it requires to be done and

that is what is being done...We [DIAC officers] are trained and briefed, and we

apply their guidelines as we do around the world on this issue.[551]

6.78

The Committee understood from this evidence that DIAC officers are

involved in measuring people against criteria, determined by ASIO, to assess

which cases need to move to a more in-depth security check.

6.79

ASIO was also asked about this process, and informed the Committee that

ASIO and DIAC had agreed in May 2011 that all security triaging would be

performed solely by ASIO:

Prior to and following the commencement of the Framework in

April 2011, ASIO provided Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC)

officers with training on the implementation of the security indicators. ASIO

also established appropriate administrative procedures to enable DIAC to

undertake this function as directed by Government in December 2010.

Since June 2011, all triaging pursuant to the framework is

undertaken by ASIO; this includes establishing the security criteria as well as

implementing and applying the criteria for security assessment referral.

However, DIAC may provide feedback on the security indicators within the Framework

as required.[552]

6.80

The Committee noted from the evidence above that DIAC provides feedback

on security assessments, but it was not entirely clear when and if DIAC

officers make referral assessments without involvement from ASIO. The Committee

was informed by DIAC that the two organisations work closely together in this

regard, and that 'there is a symbiotic interdependency' between them.[553]

6.81

The criteria for referral were not disclosed by ASIO for security

reasons.

Committee view

6.82

The Committee notes evidence that the new intelligence-led assessment

framework established by ASIO in March 2011 has, according to evidence from

DIAC Secretary Andrew Metcalfe, 'vastly reduced the number of people in

long-term detention.'[554]

The Committee considers this a very positive initiative and commends both ASIO

and DIAC for their work in implementing the new framework.

Process for asylum seekers going

into community detention

6.83

The Committee heard that ASIO conducts a particular security assessment for

anyone DIAC decides to release into the community. This assessment, however, is

a much shorter, simpler process than that undertaken in order to issue a

permanent visa. This shorter process is

able to be completed in around 24 hours, and gives ASIO the opportunity to

inform DIAC of any concerns regarding a particular individual before that

individual is placed in community detention.[555]

6.84

Furthermore, this shorter assessment is already routinely performed for every

refugee referred to ASIO by DIAC, whether in community detention or a detention

facility, prior to the more in-depth assessment taking place.[556]

6.85

The Committee notes that ASIO is not prevented or inhibited in any way

whatsoever from performing in-depth security assessments once people are in

community detention:

At the moment Immigration is referring to us anyone it wishes

to release into community detention. That does not prejudice in any way our

ability subsequently, once they have been declared 1A met, to conduct a much

different assessment process.[557]

Concerns around security assessments

6.86

The Committee took a great deal of evidence on the issue of security

assessments. These can broadly divided into three themes:

1. The length of time taken to

complete security assessments.

2. The need to detain people for

the duration of the assessments.

3. Adverse assessments and the

lack of opportunity for review.

6.87

Given the undeniable impact of prolonged detention on mental health and

the serious consequences of an adverse security assessment, the Committee spent

considerable time examining the security assessment process and evaluating the

criticisms levelled at it.

Length of the process

6.88

As previously stated, the indeterminate duration of the security

assessment process has been identified as a major contributing factor to

distress among detainees.

6.89

The Committee heard that round 80 per cent of ASIO assessments are

completed in less than a week. It can take many months to complete security

assessments for the other 20 per cent of cases which are more complex and

time-consuming.[558]

6.90

ASIO contended that its security assessments were not the primary factor

in lengthy processing times:

At 12 August 2011, there were around 5,232 irregular maritime

arrivals in immigration detention, of which 448 had been found to be refugees and

were awaiting security assessment – this represented eight per cent of those in

detention at that time.[559]

6.91

ASIO also stated:

Processing priorities for security assessments and the order

in which they were progressed were also directed by DIAC. For example, prior to

May 2010 DIAC directed complex, long-term IMA detention cases be afforded lower

priority for security assessment, in order to clear less-complex cases to

address serious accommodation limitations on Christmas Island.

In early 2010, ASIO undertook a review of its internal

assessment process, with a view to streamlining and improving through-put. As a

result, processing times were sped up and additional resources assigned to the

security assessments function. These measures were, however, overtaken by the

rapid increase in IMA arrivals throughout the year.[560]

6.92

Evidence provided by the Director-General of ASIO indicated that a small

proportion of cases take significant time to resolve. Mr Irvine spoke of the

number of people in detention awaiting security clearances:

At the moment, we reckon that about 80 per cent of our

assessments are completed in less than a week. The 20 per cent or less of

remaining cases are what we call complex cases, which do require a much longer

time if you are going to do a thorough assessment, basically with cause. At the

moment, out of however many people are currently in detention, in community

detention or are awaiting the conclusion of the process, there are 463 people

awaiting a security assessment from ASIO.[561]

6.93

Mr Irvine also confirmed for the Committee that ASIO would be able to

conduct its in-depth security assessments while asylum seekers were in

community detention or on bridging visas while their applications for

protection were being processed.[562]

Committee view

6.94

From the evidence provided by ASIO, the Committee understands that

placing people in community detention following an initial, routine security

check does not prejudice any subsequent, in-depth security assessment ASIO may

provide prior to a permanent visa being issued and a refugee being released

into the community. From this it follows that refugees whose initial security

checks do not produce red flags could be placed in community detention while

their in-depth assessment is underway. The Committee is of the view that asylum

seekers found to be refugees should therefore be taken out of detention

facilities and placed in community detention, unless initial ASIO checks

produce cause for concern.

6.95

The Committee recognises that refugees in detention awaiting ASIO

security assessments comprise a relatively small portion of the detention

population. The Committee also recognises that people in this category have not

yet passed the in-depth security assessment required for a permanent visa, but

notes that they have cleared initial security checks, and that placement in

community detention does not prejudice ASIO's ability to conduct in-depth

assessments. The Committee is therefore of the view that refugees who pass

initial security assessments are of sufficiently low risk to national security

to be transferred from detention facilities to community detention while

in-depth security assessments are completed. This would significantly reduce

the amount of time refugees who are not deemed to be a risk to national

security spend confined in detention facilities.

Recommendation 26

6.96

The Committee recommends that the Australian Government move to place

all asylum seekers who are found to be refugees, and who do not trigger any

concerns with the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation following

initial security checks, and subject to an assessment of non-compliance and

risk factors, into community detention while any necessary in-depth security

assessments are conducted.

Adverse assessments and the lack of

opportunity for review

6.97

Ultimately, security assessments can determine the outcome of a person's

bid for asylum in Australia. When a person is found to be a refugee but

receives an adverse security assessment, the nature of that assessment (which

is not known to them) in most cases results in the refugee not being able to

gain entry into the Australian community, irrespective of any genuine need for

protection. There are a considerable number of people currently detained in

Australia's immigration detention facilities that have been assessed as genuine

refugees but have nonetheless received adverse security assessments.

6.98

Being a signatory to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of

Refugees (the Refugee Convention) and its 1967 Protocol Relating to the

Status of Refugees (the Protocol), Australia does not refoule (return) 'people

to countries where they have a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of

race, nationality, political opinion or membership of a particular social

group.'[563]

A consequence of this policy is that refugees who receive adverse security

assessments can be left, effectively, in indefinite detention. Many have been

kept in detention for significant periods of time, with no resolution to their

individual cases in sight. Some have children who were born, or are growing up,

in detention facilities. Adverse security assessments mean people cannot be

released into the community or sent to third countries, but their refugee

status means they cannot be repatriated.

6.99

As previously noted, ASIO does not decide what action to take once it

makes an adverse security assessment. ASIO simply provides advice to DIAC,

which acts on an assessment:

The consequences of an ASIO security assessment depend on the

purpose for which it is made, and the relevant legislation, regulation or

policy. In most visa categories, a visa may not be issued (or be cancelled)

where ASIO determines the applicant to be directly or indirectly a risk to

security. The enabling legislation in this instance is the Migration Act

1958, especially the Migration Regulations 1994 and public interest

criterion 4002. ASIO itself is not permitted by the ASIO Act to take any

administrative action.[564]

6.100

The Committee notes ASIO's assurance that adverse assessments are not

made easily, or often:

I think it is important to put on the record that ASIO is, in

fact, highly discriminating in the use of such assessments. We issue them only

when we have strong grounds to believe that a person represents a security

threat. That is reflected in the relatively small number of adverse security

assessments issued. Of the nearly 7,000 security assessments that we have

undertaken since January 2010, in relation to IMAs, we have issued only 54

adverse assessments and 19 qualified security assessments. That represents

about one per cent of IMA security assessment cases. We therefore do not take a

decision to issue an adverse security assessment lightly and nor are we

contemptuous of or blase about the human rights of the individuals

involved. We take very seriously our responsibility to behave ethically and

professionally and, obviously, with the utmost probity.[565]

6.101

However, refugees with adverse security assessments do not have legal

recourse to a review of this assessment. The impossible situation these people

are in is perhaps one of the greatest challenges currently facing the

immigration detention system. The next section addresses this point.

What to do with the hard cases

6.102

Even though the overall detention population decreased during 2011, the

number of asylum seekers held in detention for longer than 12 months saw a

significant increase since September 2010.[566]

The Department informed the Committee that this was in large part due to an

increase in the number of detainees on negative pathways; that is, those who

received negative initial decisions which were subsequently under review.

Negative pathway cases present significant detainee management challenges, and

their growth has contributed significantly to the burden of the detention and

asylum processing systems.[567]

6.103

The Department also cited the following exacerbating factors:

-

the significant and rapid increase in the number of arrivals in

2010

-

increasing complexity of claims

-

new cohorts of IMAs with different claims

-

changes to country of origin information resulting in greater

complexity of assessments for clients seeking asylum

- changing country information also resulted in the temporary

suspension of processing of new asylum claims from people from Sri Lanka and

Afghanistan for periods of three and six months respectively

-

difficulties in determining clients’ identity and, in some

instances, their country of residence

-

infrastructure pressures and detention incidents limiting access

to some IDFs

-

completing third country checks

-

processing times for completion of security assessments

-

the need to reconsider a number of client decisions at the

Independent Merits Review stage resulting from the November 2010 High Court

decision.[568]

6.104

There are currently, broadly speaking, two groups of people in

prolonged detention: confirmed refugees who failed the security test and

therefore cannot be released or returned to their country of origin, and people

who have failed to gain refugee status but still cannot be deported or

repatriated. Although their bids for protection failed before any

security assessment even occurred, these people also effectively find

themselves in indefinite detention.

Non-refugees who cannot be

repatriated

6.105

A growing number of cases have become subject to protracted delays due

to delays in obtaining the documentation necessary for repatriation. The Department

advised the Committee that difficulties in securing travel documents for these

people is likely to become an increasing problem for some cohorts,

'particularly where governments of other countries are reluctant to facilitate

involuntary return of their nationals.'[569]

Similarly protracted delays have been identified in securing return options for

stateless asylum seekers who are not found to be refugees.[570]

Refugees in indefinite detention

6.106

In other instances, some refugees are being held in what amounts to indefinite

detention. They have no prospect of release or deportation, and no legal right

to a merit review of their adverse security assessment.[571]

Significant concerns about the ethical and moral implications of issuing a security

assessment which indefinitely removes liberty without disclosing evidence of

the justification for such an assessment were expressed.[572]

6.107

The Committee also received comprehensive evidence from legal experts on

the matter. The evidence before the Committee outlines why these legal experts

specialising in security, human rights and refugee law have concluded that

Australia is in breach of its obligations under international law.[573]

Professor Jane McAdam from the Gilbert and Tobin Centre of Public Law,

University of New South Wales (UNSW), unequivocally stated:

Australia’s policy of mandatory detention undeniably violates

this country’s obligations under international law. Countless international and

domestic reports have explained why this is so, including those by the UN Human

Rights Committee, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, the UN Committee

on the Rights of the Child, the UN Committee Against Torture, the UN Committee

on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right

of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and

Mental Health; the Australian Human Rights Commission, and many reputable

international and national human rights NGOs.[574]

6.108

The Committee was informed that under Australian law only some

individuals have recourse to a review of adverse security assessments:

Qualified or adverse ASIO security assessments may be

appealed to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) if the applicant is an

Australian citizen or permanent resident, or holds a special visa or special

purpose visa. Non-Australian citizens who are applying for a visa are entitled

to file an application in the Federal Court or High Court and seek judicial

review in respect of an adverse security assessment. Such a review involves a

court's determining the legality of administrative decisions and does not

extend to the merits.[575]

6.109

Professor Ben Saul from the Sydney Centre for International Law explained:

[Refugees] are unable to effectively challenge the adverse

security assessments issued by ASIO, upon which the decisions to refuse them

refugee protection visas and to detain them are based. In particular:

(i) The reasons and evidence for

their adverse security assessments have not been disclosed to them, because

ASIO has decided to refuse any disclosure to them (including even a redacted

summary);

(ii) They enjoy no statutory

rights to judicially challenge their assessments under the Australian Security

Intelligence Organisation Act 1979 (Cth) (‘ASIO Act’), or to review the merits

of the assessments before any administrative tribunal;

(iii) Australian courts are not

empowered to review the substantive ‘merits’ of adverse security assessments,

but are confined to limited judicial review of them for errors of law

(‘jurisdictional error’);

(iv) Such judicial review at

common law is practically unavailable, because Australia has not

disclosed to them any reasons for, or evidence substantiating, their adverse

security assessments, and they are therefore unable to identify any prima facie

errors of law which would permit them to legitimately commence proceedings,

without risking abuse of the courts’ process and incurring costs orders;

(v) They are unable to compel

disclosure of the reasons for, or evidence substantiating, their adverse

security assessments, both because the courts have accepted that procedural

fairness at common law is reduced to ‘nothingness’ in their circumstances (as

long as the ASIO Director-General has given genuine consideration to whether

disclosure would not prejudice national security), and/or public interest

immunity would preclude disclosure to them anyway; and

(vi) There is no other special judicial

procedure enabling their adverse security assessments, and thus their

detention, to be tested to the standard demanded by article 9(4).[576]

6.110

Examples were cited, including:

The ASIO adverse security assessments are a real problem. As

you know, there is no appeal process available. I met a man in Scherger who has

evidence that he showed me. ASIO had issued him with an adverse security

assessment because of his activities in Sri Lanka during a given period of

time. He showed me his documents saying he was not there; he was in a refugee

camp in India. What opportunity he has he got to appeal? We have written to

ASIO and we have written to the IGIS. What opportunity does he have to make a

case? None. Currently there is a 17-year-old boy. He left his country as a

teenager. He is stateless. He is illiterate; he is not even literate. He has

never been to school. He has been assessed as a security risk. We have grave

concerns about the indefinite nature of the detention of people.[577]

6.111

Notwithstanding the impact indefinite detention is having on mental

health, there is a genuine national security concern that must be addressed

within the framework of any solution to this seemingly intractable problem. The

Committee noted that those seeking a right of appeal for refugees in indefinite

detention accepted that some people may pose a risk to national security which

must be addressed:

There obviously is always justification for detaining certain

people who may be a national security risk, but in every circumstance like that

the Law Council has always argued that the reaction needs to be proportionate

to the particular threat that that person poses. So that question needs to be

examined in each individual case and there needs to be provision for review of

that if different circumstances come to light, or different information comes

to light. At the moment, there is no opportunity for review of that assessment.[578]

6.112

Mr Richard Towle, the Australian representative of the United Nations

Commissioner for Human Rights, spoke of the need, and ways, to balance national

security with fairness:

We have proposed in our submission a practice that is used in

several countries around the world—Canada; New Zealand, my home country; and

the United Kingdom—where a bridge can be built between the security assessment

and the confidentiality surrounding that and the right for someone to know at

least the basic elements of the case against him or her. That is an appropriate

way of finding a balance between often two competing sets of interests.[579]

6.113

The Committee pursued the matter with Mr David Irvine, Director-General

of ASIO, who explained that even the criteria—let alone specific reasons in

individual cases—for issuing adverse assessments were not able to be released:

Once the criteria for making assessments are known, then you

will find very quickly that all the applicants will have methods of evading or

avoiding demonstrating those characteristics.[580]

6.114

A submission from Professor Saul, from the University of Sydney, contended

that not providing evidence upon which the assessment is based is a violation

of article 9(4) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR):

Where detention is purportedly justified by a State on

security grounds, the requirement of substantive judicial review of the grounds

of detention under article 9(4) necessarily requires a judicial inquiry into

the information or evidence upon which a security assessment is based. Without

access to such evidence, a court is not in a position to effectively review the

substantive grounds of detention.[581]

6.115

Currently, however, Professor Saul explained that refugees merely

receive letters 'cast in near-identical terms', which state:

'ASIO assesses [author name] to be directly (or indirectly) a

risk to security, within the meaning of section 4 of the Australian Security

Intelligence Organisation Act 1979.'[582]

6.116

The Director-General of ASIO reiterated to the Committee that it was not

ASIO's decision to deny opportunity for review, but that the law as it stands

would only permit Australian citizens and a few select categories of people to

appeal against ASIO assessments. He drew the Committee's attention to the words

of Justice Robert Hope in 1977:

At that time he considered the whole question of appeals

against the ASIO assessment process. He recommended that Australian citizens,

and a few other categories of people, should be allowed to appeal but he

recommended against appeal rights for noncitizens. What he wrote was this:

The claim of noncitizens who are not permanent residents but

who are in Australia to be entitled to such an appeal is difficult to justify,

particularly as they have no general appeal, and I shall recommend that they

shall have no such right.

That was actually taken up in section 36 of the [ASIO] act.

That is the legal basis on which we are operating.[583]

Refugees with adverse assessments

already living in the community

6.117

The Committee sought evidence from ASIO concerning precedents for people

with adverse security assessments being released into the community. The Committee

noted one case in which a family had received an adverse assessment in 2002,

but had since been released. The Committee pointed out that in this particular

instance, the asylum seekers in question applied for protection visas onshore

having arrived by plane—that is, they were not IMAs—and sought clarification on

whether refugees deemed to be a potential threat to national security were

being treated differently depending on their means of arrival.

6.118

The Committee was informed by the Director-General of ASIO that such

people were subject to a high degree of resource-intensive monitoring:

I am comfortable—that is probably not the word I would

use—with a very small number, but I simply would not have the resources to

provide the level of monitoring and so on that would be required over a long

period of time for anyone with an adverse assessment to be in the community...

...I do not want to go into it too deeply, but the question

then reflects on the levels of quality of monitoring and the quality assurance

that I can give the government in terms of national security considerations. It

is a concern.[584]

6.119

The Committee notes that the Council for Immigration Services and Status

Resolution (CISSR)[585]

had earlier discussed options for undertaking risk analysis of refugees with

negative security assessments:

The Chair raised the idea of using the National Security

Monitor to undertake risk analysis of negative security assessments. He saw as

appropriate the use of an independent person to look at the application of

security assessment of people in detention and the risk they pose.[586]

6.120

Minutes from the CISSR meeting in question, however, do not indicate

that a workable way forward was identified:

...[T]he National Security Monitor is a relatively new role

set up under legislation to deal primarily with counter-terrorism issues. It

was not intended to be used in the way suggested by the Council and she would

prefer to speak with Duncan Lewis at Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C)

about pursuing this avenue before preparing a proposal for the Minister.[587]

Committee view

6.121

The Committee reiterates its concern regarding the indefinite detention

of refugees with adverse security assessments. While the Committee understands

and appreciates that these questions are necessarily viewed through the prism

of national security, the Committee remains deeply troubled by the fact that those

with adverse assessments cannot obtain evidence-based justifications for their

status, and is mindful that assessments effectively determine people's freedom

and, in many cases, that of their children.

6.122

The Committee notes ASIO's view that disclosing reasons behind a

negative assessment to the individuals in question could impact on ASIO's

ability to gather reliable background information. However, the Committee is

not convinced that disclosing relevant information to a security-cleared third

party, or a security-cleared legal representative of the individual, would be

so detrimental as to justify detention without charge for the term of the

individual's natural life.

6.123

Furthermore, being aware that a number of refugees have received

permanent visas and are living in the community despite adverse security

assessments, the Committee believes that ASIO is able to discern varying levels

of risk posed by individuals with adverse security assessments.

6.124

The Committee is of the view that the government should take immediate

steps to resolve how best to afford refugees an opportunity to appeal the

grounds for their indefinite detention without compromising national security,

and it is this matter to which the chapter now turns.

Establishing a right of review

6.125

The Committee explored various ways in which a right of review of

security assessments could be established. In particular, the Committee notes

Professor Ben Saul's reference to Article 9 of the International Covenant

on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), whereby decisions to prolong detention

require periodic reviews so that the grounds for detention can be assessed:

Thus, even if detention may be initially justified on

security grounds, article 9 requires periodic review of such grounds and

precludes indefinite detention flowing automatically from the fact of original

grounds justifying detention.[588]

6.126

The Committee heard from ASIO that it would work within any legal

framework that was established:

Whether IMAs or any other applicants for visas who are

rejected on security grounds should be afforded merits review is essentially a

matter for the government. Should the government introduce a merits review

process for IMAs who are subject to adverse or qualified assessments, we will

then work within that legal framework.[589]

6.127

The Committee asked Mr Irvine whether he could foresee negative implications

arising from that right being established:

I think that is advice I would have to give the government.

But what I would say is: there are a number of factors that you would need to

take into account...What form of merits review would you have? Where would it

go? What protections for other national security considerations would you have,

including as far as I am concerned elements of national interest but also

sources and methods for ASIO? What is the scope of that process? Would merits

review apply to someone who we knocked back as a suspected spy for a foreign

power, someone we gave an adverse assessment to on the basis that we thought

that person might be coming to Australia to pursue the acquisition of parts of

weapons of mass destruction or something like that or to conduct sabotage? How

would the merits review process in those circumstances protect us from a

foreign government probing our sources and methods and so on? You would need to

be very careful about how you applied such a process. Subsequently, there would

be all sorts of resource and other implications, but that would be something

for the government to decide.[590]

6.128

The Committee also spoke to Dr Vivienne Thom, Inspector-General of

Intelligence and Security. Dr Thom informed the Committee that of 1111

complaints concerning ASIO's handling of security assessments for visa reasons

in 2010-11, only 27 per cent related to refugee visa applications. The others

were mostly made by offshore visa applicants. The number of complaints issued

by refugees in detention totalled 209, with this figure being comparable to

previous years.[591]

Dr Thom stressed that her reviews of ASIO processes did not currently extend to

merit reviews of its decisions:

We can look at the process that ASIO has followed, to ensure

that it is lawful and proper. For example, we look to see whether the correct

legal tests and thresholds were satisfied and whether the relevant ASIO officer

was authorised to take action.[592]

6.129

Dr Thom discussed the possibility of review rights being extended to

noncitizens:

I note that one of my predecessors, Mr Bill Blick, in his

1998-99 annual report recommended to the then Attorney-General that the

government introduce legislation to provide a determinative review process for

refugee applicants where they have valid asylum claims. It is worth noting that

at the time he said it would apply to no more than a handful of cases in any

one year. It should also be remembered that Mr Blick's comments were made 12

years ago, prior to 9-11 and in a different environment. In the 2006-07 annual

report, while not endorsing Mr Blick's recommendation, Mr Ian Carnell said that

he thought it would be worthwhile revisiting this proposal. Mr Carnell also

noted at the time that the number would be very small and hence cost would not

be a barrier. I would comment that I do not disagree with Mr Carnell's

suggestion that perhaps it is appropriate to re-examine this issue. It is a

matter that is attracting major public attention, but it is a complex matter

that will require careful consideration of national security issues and the

rights of individuals, because these decisions do have serious impacts on

individuals.[593]

6.130

The Committee sought many views in looking for a way to balance the

situation of refugees in indefinite detention with national security

considerations. The Law Council of Australia stated:

There are a number of options that are on the table. One is

that the committee could look at removing the current restriction for people to

apply for merits review of their security assessment in the Administrative

Appeals Tribunal. That restriction does not apply to Australian citizens but it

does apply to noncitizens. One recommendation which has been made both by the

Human Rights Commission and the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security

is that that restriction be removed, so that people can actually test the

merits of that decision.[594]

6.131

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights pointed to

appropriate means of finding a balance between the competing interests of

national security and fairness:

We have made some suggestions around that—the possible use of

a special advocate system, the use of redacted evidence that can be looked at,

and the possible lifting of the restriction for refugee or asylum-seeker

claimants to access an appeal mechanism, such as the Administrative Appeals

Tribunal. Those are all areas where we think an appropriate accommodation or

balance can be found between these two difficult sets of issues. I can, of

course, answer more questions about that, if you wish.[595]

6.132

The Committee acknowledges widespread support for the establishment of a

merits review process for adverse security assessments. The following sections

outline review mechanisms the Committee has considered. Some of the mechanisms

may be complementary and able to be implemented simultaneously.

Internal ASIO reviews

6.133

The Committee considered the potential benefits of requiring ASIO to

conduct periodic reviews of all adverse assessments. The Law Council posited

that a negative assessment was, at present, seemingly permanent:

At the moment, our understanding is that, once you have an

adverse ASIO assessment, you have that virtually for life. There may be

information that can come to light later in the process which would justify a

review of that assessment.[596]

6.134

Although ASIO is 'always prepared if a person is referred or additional

information comes to light to revise our judgement,' there is currently no

requirement for to conduct periodic reviews. [597]

6.135

As matters stand reviews are possible but not routine. A case has to be

referred to ASIO by DIAC, or the former has to reach the decision to conduct a

review on the basis of new information that has come to light.[598]

Such reviews have not produced new outcomes in the past. Mr Metcalfe informed

the Committee that he could recall only one case where a revised ASIO

assessment resulted in a different outcome for someone:

The only case that I can recall of a reconsideration which

resulted in a person being treated differently was one of the last [people]

detained on Nauru and who was brought to Australia because of severe mental

illness. In that case, ASIO subsequently revised their opinion and indicated

that the person was not a security concern. Of the current case load, there is

no appeal mechanism against an adverse security assessment of a person who is

not a visa holder, and that of course is a policy matter for the

Attorney-General.[599]

Expanding the powers of the Federal

Court

6.136

Another option considered by the Committee was that of a panel of

security-cleared Federal Court judges reviewing evidence, with refugees subject

to adverse ASIO assessments being represented by security cleared lawyers, otherwise

known as special advocates. Professor Ben Saul explained special advocate

procedure in place in Britain, Europe and Canada:

The function of a special advocate is twofold. Firstly, they

have a role in testing the government’s argument that the evidence or

information cannot be safely disclosed, and then if they win that argument and

the evidence can be safely disclosed to the person, the person has a shot at

testing its merits before the procedure. If it is not admitted, the special

advocate then performs a second function, which is making submissions on behalf

of the client, without instructions from the client, about the reliability of

the evidence on the merits. So at least somebody then is testing the merits of

the evidence.[600]

6.137

Were a similar system to be adopted here, one of the key changes be a

broadening of what judges could examine or test. At present, judges may on

occasion look at evidence or lawyers may receive security clearance on an ad

hoc basis. However, judges are currently empowered to look only at errors

of law, not the merits of a case.[601]

6.138

The Committee sought views on how well such a system would function in

place of a tribunal, were the law to be changed so that a judge could have

broader powers of testing the merits of a particular security assessment,

whilst satisfying ASIO's concerns about revealing sensitive information.

Professor Saul was of the view that expanding the powers of the Federal Court

in such a way would be possible, and explained different versions of the

concept:[602]

You could do it where the person gets to see the information

and test it before that procedure, or you could do it in the more limited

compromised fashion, which is through the special advocate process, which is

what happens in the Special Immigration Appeals Commission in the UK and in a

different manner in Canada. I think the broader point is that it would

certainly enhance public confidence in justice if you had a federal judge

involved in some kind of process like that and it would go a long way towards

meeting Australia’s international human rights obligations to provide a fair

hearing in these cases.[603]

6.139

The Gilbert and Tobin Centre of Public Law within the University of New

South Wales Faculty of Law (Gilbert and Tobin) had reservations about such a

proposal:

In our opinion, the constitutional impediments to reposing in

a Chapter III court the powers to review both for errors of fact and of law

would prevent the Federal Court from exercising a true merits review function

over security assessments made by ASIO. This is an executive function which

cannot be exercised by a court constituted under Chapter III of the