Regional overview |

| 2.1 |

The countries of North Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia) share similar climatic and geographical characteristics, but they differ in terms of their economic progress and social and political development. The Algerian and Libyan economies are dominated by the oil and gas sectors, others rely on tourism, agriculture and light industry.1

|

| 2.2 |

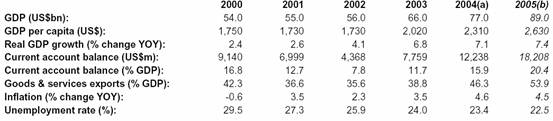

Economic development in some countries has been affected by political instability, including civil war in Algeria during the 1990s. During the same period Libya was subject to international sanctions. The conflict between Morocco and Algeria over Western Sahara has also had a negative impact on the economies of both countries.2 Table 2.1 summarises significant economic indicators, and each country is considered individually under Economies of North Africa below.

|

| 2.3 |

The combined population of Algeria , Egypt , Libya , Morocco and Tunisia is over 155 million—a significant market that offers opportunities for Australian exporters and investors in a range of

sectors. A high birth rate is common to all countries of the region, which presents social and economic challenges such as job creation and the need for improved economic growth. 3

|

Algeria (a) |

Egypt (a) |

Libya (a) |

Morocco (a) |

Tunisia (b) |

Population (million)5 |

33.4 |

73.3 |

5.7 |

31.1 |

9.9 |

GDP (US$ bn) |

54.1 |

82.6 |

14.2 |

38.4(b) |

21.1 |

GDP per head (US$) |

1,677 |

1,168 |

2,552 |

1,297 |

2,160(a) |

GDP per head (US$ at PPP) |

4,655 |

3,628 |

10,933 |

4,044 |

6,503(a) |

Consumer price inflation (av;%) |

2.3(b) |

2.7 |

1.1 |

2.8 (b) |

2.8 |

Current-account balance (US$ bn) |

6.9 |

0.5(b) |

6.9 |

0.6 |

-0.7 |

Current-account balance (% of GDP) |

12.8 |

0.7 |

48.4 |

1.6 |

-3.5 |

Exports of goods fob (US$ bn) |

19.8 |

7.0(b) |

11.7 |

7.7(b) |

6.9 |

Imports of goods fob (US$ bn) |

-10.6 |

-14.7 (b) |

-3.6 |

-10.8(b) |

-9.0 |

External debt (US$ bn) |

21.7 |

29.1 |

4.4 |

16.8 |

12.6(a) |

Debt-service ratio, paid (%) |

15.0 |

10.1 |

6.1 |

18.5 |

14.4(a) |

Source Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Data. |

|

|

North African trade links |

Global |

| 2.4 |

Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia are all members of the World Trade Organisation. Algeria expects to join the organisation shortly, subject to settlement on several outstanding issues and Libya is in the early stages of its accession process.6

|

| 2.5 |

Some North African countries have also signed, or are exploring, free trade agreements with countries that are Australia’s competitors in some sectors:

- Morocco concluded a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the USA in 2004 and, the committee was told during its visit, envisages integration with the EU within ten years.

- Egypt has been seeking to negotiate an FTA with the USA in recent years. The USA wants to see Egypt make more progress on the reform and modernisation of its political and economic systems before negotiations can begin;7 and

- Tunisia has a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement with the USA.8

|

Mediterranean |

| 2.6 |

The Arab Maghreb Union was established in 1989 and is intended to help its member countries ( Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia) harmonise their economies and promote trade. Conflict between Algeria and Morocco over the latter’s claim of sovereignty over Western Sahara has stopped Union meetings since the early 1990s, but it does provide a framework within which to pursue regional trade. 9 Egypt is currently in the process of joining the Union.10

|

| 2.7 |

Tunisia, Egypt, Morocco, and Libya are part of the Arab Free Trade Zone, with Algeria in the process of becoming a member. The zone, inaugurated in January 2005, eliminates taxes on inter-regionally traded agricultural products and ends the need for certificates of origin.11

|

| 2.8 |

In February 2004 Tunisia, Egypt, and Morocco, together with Jordan, entered into theAgadir Agreement for the establishment of a free trade zone due to come into operation in early 2006.12

|

European |

| 2.9 |

In addition to regional trade opportunities, the countries of North Africa are keen to take advantage of their proximity to Europe , but

without over-reliance on commercial ties. Thus they are seeking to expand their trade and investment activity where appropriate.

|

| 2.10 |

The trading links between Europe and North Africa have been formalised to a degree in arrangements such as the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership and the European Neighbourhood Policy (see box below)13

The Euro-Mediterranean Partnership and the countries of North Africa14

The Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (also known as theBarcelona Process) was launched by a meeting of Foreign Ministers of the European Union and countries of the southern Mediterranean at a conference in Barcelona in November 1995.

The Partnership comprises the 25 EU member states and 10 Mediterranean partners ( Algeria , Egypt , Israel , Jordan , Lebanon , Morocco , the Palestinian Authority , Syria , Tunisia and Turkey ). Libya has observer status.

The objectives of the partnership include the definition of a common area of peace and stability through the reinforcement of political and security dialogue, construction of a shared zone of prosperity through an economic and financial partnership and the gradual establishment of a free trade area, and rapprochement between peoples through a social, cultural and human partnership.

The partnership involves a bilateral and a regional dimension. Bilaterally, the EU negotiates association agreements with individual Mediterranean partners. The regional dimension encourages regional cooperation in support of the objectives of the Partnership.

According to recent statements efforts are continuing towards the establishment of a Euro-Mediterranean Free Trade Area by 2010.

The more recent European Neighbourhood Policy of the EU aims to build on, and complement, the Barcelona Process and create enhanced relationships with Europe ’s neighbours based on shared values and common interests.

|

|

| 2.11 |

Overall, opportunities for increase Australian interaction with the North African countries, but exist, but are currently less extensive than those with the neighbouring Arab Gulf States.15

|

|

|

Economies of North Africa |

Algeria |

| |

Source: DFAT Country Factsheets, http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/fs/algr.pdf

|

| 2.12 |

Algeria's economy is dominated by its oil and gas sector. The sector accounts for around 95% of Algeria's export earnings. Algeria has approximately 2.6% of total world natural gas reserves and holds 35% of Africa's proved reserves. It is the world's second largest LNG producer (after Indonesia) and the fourth largest exporter of natural gas.17

|

| 2.13 |

The sector accounts for approximately 52% of budget revenue, 25% of GDP and over 95% of export earnings.18 High world oil prices have boosted Algeria’s overall economic performance. Algeria’s oil production in 2004 was 1.4 million barrels per day (mbd). In 2005 production is expected to reach 1.5 mbd. Natural gas production rose in 2004 by 5% to 144.3 billion cubic metres.19

|

| 2.14 |

Despite the internal unrest of the 1990s, Algeria’s economy has performed well in recent years. In 2004 it recorded a growth rate of 5.4%, modest inflation, and a small decline in chronic unemployment levels. The OECD expects the Algerian economy to grow by 4.5% in 2005. |

| 2.15 |

This economic performance is largely due to the contribution of its oil and gas sector, but the government has implemented some important

policies designed to reduce reliance on hydrocarbon exports, and bring greater diversity to Algeria ’s economy.20 |

| 2.16 |

Algeria still faces some difficult social and economic problems. Unemployment remains very high, affecting both urban and rural areas in roughly equal measure. The average official unemployment level is 22.5%, but in the 20 to 24 year old age group unemployment is assessed to be 43.9%.21

|

| 2.17 |

The oil and gas sector employs only 3% of the work force. Although dwarfed by the size of the hydrocarbon industry, the construction, agriculture and services sectors are important contributors to the economy.22

|

| 2.18 |

The Algerian government has won the praise of the IMF and OECD for its efforts to modernise its economy and to manage effectively Algeria’s oil and gas revenues. In August 2004 the Algerian government established a US$40 billion economic growth support plan comprising major infrastructure projects focusing in particular on roads, railway construction, airports and sea ports. This should help further to alleviate unemployment and boost Algeria’s import requirements, while building communications and transport networks that can support efforts to diversify Algeria’s economy.23

|

|

|

Egypt |

| |

Source: DFAT Country Factsheets, http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/fs/egyp.pdf

|

| 2.19 |

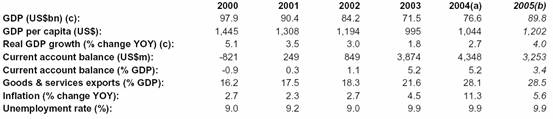

Egypt is the most populous country in the Arab world and has the second highest population (estimated at 76 million in 2004) in Africa after Nigeria. About 90% of the population lives along the Nile.25

|

| 2.20 |

It has the second largest economy in the Arab world after Saudi Arabia, with GDP estimated at US$85 billion in 2004. Egypt's principal sources of foreign exchange are Suez Canal tolls, tourism26 , expatriate remittances and petroleum exports. Services make by far the biggest contribution to value added (more than half of GDP). Agriculture has declined in recent decades and now contributes less than 20% of GDP. Manufacturing industry accounts for the remainder.27

|

| 2.21 |

In the early 1990s, Egypt embarked on a program of structural reforms, including further reduction of the budget deficit and inflation, privatisation of public enterprises, further trade liberalisation and business deregulation. The new government appointed in July 2004 has moved to revive the economic reform program. Key measures have included lowering customs duties, simplifying customs procedures, 28 tax reforms and accelerating the privatization program.29

|

| 2.22 |

Real GDP was forecast to rise by 4.0% in 2005, up from an estimated 2.7% in 2004. The unemployment rate was expected to fall to 10% in 2005, from 10.9 % in 2004.30

|

|

|

Libya |

| |

Source: DFAT Country Factsheet, http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/fs/lbya.pdf

|

| 2.23 |

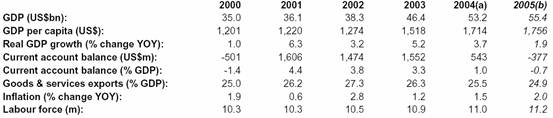

In recent years international competition for business in the Libyan market has grown rapidly. United Nations’ sanctions against Libya were lifted in September 2003. This was followed a year later by the lifting of sanctions that had been imposed by the United States. Following Libya’s international rehabilitation (based on its renunciation of terrorism and of its programs for the development of weapons of mass destruction) the Libyan government has made clear its intention to re-integrate into the global economy. The reform process it has embarked upon has been, in some respects, hesitant and piecemeal and largely non-transparent. While the government has committed itself to enhancing the role of the private sector, Libya’s economy remains under firm central control.32

|

| 2.24 |

Libya’s current economic performance is favourable, and its external position, thanks to continuing strong world oil prices, remains robust. The IMF estimates that in 2003 Libya’s GDP grew by 9%. Non-oil activities contributed only 2.2% cent to the overall growth figure. In 2004 real GDP growth was estimated to be around 4.5%, the decline reflecting a drop in the growth of oil production.33

|

| 2.25 |

In evidence to the committee, Woodside’s assessment of the oil sector was that it had advantages over other producers in its high quality, low sulphur 'sweet' crude oil, proven reserves (more than 3% of the world's total oil reserves), production costs which are among the lowest in the world, and its proximity to the markets of Western Europe compared to Middle East exporters.34

|

| 2.26 |

Libya’s pattern of trade points to a strong relationship with the main economies of the EU - that is Italy, Germany, France and Britain. But the lifting of UN and US sanctions has opened the door to US companies which have been precluded from doing business with Libya for over a decade. In the coming years, competition for Libya’s business will intensify, but overall opportunities will continue to grow also.35

|

| 2.27 |

Looking at future prospects, economic growth will remain strong, underpinned by high international oil prices. The Libyan government’s commitment to economic reform has been clearly stated and there is no sign that it will revise the broad direction it is now heading in. Practical difficulties in implementing the reforms are substantial. Delays and disappointments are likely to be encountered in the short to medium term.36

|

|

|

Morocco |

| |

Source: DFAT Country Factsheet, http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/fs/moro.pdf

|

| 2.28 |

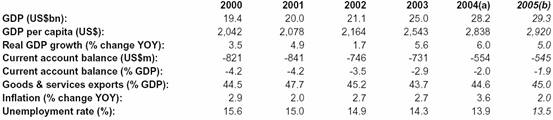

Morocco has come to be regarded as something of an exemplar among the countries of North Africa for its commitment to political, economic and social reforms that have transformed the country into one of the most open and progressive in the Arab world. Morocco’s economy performed well in 2003 and 2004, underpinned by policies that have created improved conditions for business and for investment.38

|

| 2.29 |

Morocco’s real GDP rate of growth in 2004 was 3.5% compared to 5.6% growth the previous year, reflecting Morocco’s continuing reliance on its agriculture sector and the vagaries of climate. The primary sector employs 45% of the total active population and 60% of the total female active population.39

|

| 2.30 |

Prospects for further economic advances in Morocco remain good. Under King Mohamed VI the authorities are committed to the further modernisation of both society and the economy. Democratic institutions continue to be strengthened, and open, competitive economic and business conditions continue to be encouraged. The government remains firmly committed to a reform program designed to promote human development and economic growth, reduce the vulnerability of agriculture to drought and improve public governance. Continued economic growth and sound macroeconomic policy underpin the growth of a more sizeable middle class in Morocco . This community, bolstered by large numbers of European

tourists which visit the country annually, is creating new market opportunities.40 |

|

|

Tunisia |

| |

Source DFAT Country Factsheet, http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/fs/tuni.pdf

|

| 2.31 |

Tunisia, with a population of 9.9 million, has a diverse economy, the most important sectors of which are agriculture, mining, energy, tourism and manufacturing.42 The Tunisian economic performance is one of the best in the Middle East and North Africa region.43

|

| 2.32 |

Tunisia was the first country in North Africa to sign as an associate member with the EU44 and its trade profile is heavily oriented towards the EU, which accounted for 81% of Tunisia’s exports and 71% of its imports in 2004.45 Tunisia has free trade agreements with Turkey, Egypt, Jordan and Morocco, and a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement with the United States.46

|

| 2.33 |

The government is keen to modernise the farming with the application of modern technology systems. Agriculture and fisheries experienced real growth in 2004 of 9% and contributed 14% of GDP.47

|

| 2.34 |

Manufacturing sectors that performed well in 2004 were food processing, chemicals and mechanical and electrical manufacturing. Tourist numbers grew by 17% to 6 million, mainly from Europe.48

|

| 2.35 |

Tunisia’s textile, clothing and footwear industry has, until recently, comprised one third of its manufacturing industry, 42.4% of its exports and 6%. Tunisia has also implemented some structural reforms within the sector to shore up its competitiveness. However, following the conclusion of a ten-year transitional program of the WTO Agreement on Textiles and Clothing in January 2005, this industry now faces difficulties and substantial job losses.49

|

| 2.36 |

Unemployment, running at 14% nationally in 2004, continues as a major priority for the government. High levels of youth and graduate unemployment are a continuing problem.50

|

| 2.37 |

The government has been reducing spending, modernising the taxation system and, since 1987, pursuing a privatisation program.51

|

| 2.38 |

Some attempts have been made to improve business conditions, reform trade policies and practices and to attract more private and foreign investment. To encourage that investment the government has developed industrial zones and improved the road, distribution and data transmission networks.52 |

| 2.39 |

According to DFAT, Tunisia’s longer term economic prospects appear positive. Although some sectors of the economy such as textiles, clothing and footware are likely to continue to be problem areas for the authorities Tunisia’s diverse economy and the long term strategies the government is implementing for structural and macroeconomic reforms should continue to ensure good economic performance.53

|

Summary |

| 2.40 |

In recent years the governments in the North African countries have made commitments to wide-ranging macroeconomic and structural reforms to modernise their economies. These reforms include a shift to market-based economies and should bring higher standards of public and corporate governance. This will open the region to trade and investment opportunities for other countries, including Australia.54

|

| 1 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 7. Back

|

| 2 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 7. Back |

| 3 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 7. Back |

| 4 |

(a) Economist Intelligence Unit estimates. (b) Actual. Back |

| 5 |

DFAT, Country, economy and regional information for each country, http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/#E Back |

| 6 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 5. Back |

| 7 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 7. Back |

| 8 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 17. Back |

| 9 |

DFAT, Submission No 9, p. 6. Back |

| 10 |

HE M Tawfik, Ambassador for Egypt, Evidence, 1/8/0/5, p. 15. Back |

| 11 |

ANIMA 18/1/05 Launching of the big Arab free trade , http://www.animaweb.org/news_en.php?id_news=236 Back |

| 12 |

Agadir Agreemen t, 25/2/04 , bilaterals.org, http://www.bilaterals.org/article.php3?id_article=2513 Back |

| 13 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 5. Back |

| 14 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 6. Back |

| 15 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 5. See Expanding Australia’s Trade and Investment Relations with the Gulf States, 2005. Back |

| 16 |

(a) all recent data subject to revision; (b) EIU forecast. Back |

| 17 |

Woodside Energy Ltd, Submission No 12, p. 9. Back |

| 18 |

Austrade, Submission No. 5, p. 9. Back |

| 19 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 9. Back |

| 20 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 9. Back |

| 21 |

In Algeria the Minister for Privatisation told the committee during its visit that unemployment was 30% but is now 17%. Back |

| 22 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 9. Back |

| 23 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 9. Back |

| 24 |

(a) all recent data subject to revision; (b) EIU forecast. Back |

| 25 |

DFAT, Egypt Country Brief, http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/egypt/egypt_brief.html Back |

| 26 |

Tourism in 2004/5 was worth $6 billion. Embassy of the Arab Republic of Egypt , Submission No. 3, p. 5. Back |

| 27 |

DFAT, Egypt Country Brief, http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/egypt/egypt_brief.html Back |

| 28 |

DFAT, Egypt Country Brief, http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/egypt/egypt_brief.html Back |

| 29 |

Embassy of the Arab Republic of Egypt, Submission No 3, p. 3. Back |

| 30 |

Table 2.3; DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 11; HE M Tawfik, Ambassador, Embassy of Egypt, Evidence, 1/8/05, p. 15. Back |

| 31 |

(a) all recent data subject to revision; (b) EIU forecast. Back |

| 32 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, pp. 12-13. Back |

| 33 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 13. Back |

| 34 |

Woodside Energy Ltd, Submission No. 12, p. 9. Back |

| 35 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 13. Back |

| 36 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 13. Back |

| 37 |

(a) all recent data subject to revision; (b) EIU forecast. Back |

| 38 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 14. Back |

| 39 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 15. Back |

| 40 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 16. Back |

| 41 |

(a) all recent data subject to revision; (b) EIU forecast. Back |

| 42 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 16. Back |

| 43 |

Austrade, Submission No. 5, p.7. Back |

| 44 |

Mr A Amari, Consul General, Consulate of Tunisia, Evidence, 4/11/05, p. 30. Back |

| 45 |

Major trading partners are: France , Italy and Germany . Mr A Amari , Consul General, Consulate of Tunisia , Evidence, 4/11/05 , p. 37. Mr P Foley, Assistant Secretary, Middle East and Africa , DFAT, Evidence, 1/8/05 , p. 49. Back |

| 46 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 17. Back |

| 47 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, pp. 16-17. Back |

| 48 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 17. Mr A Amari , Consul General, Consulate of Tunisia , Evidence, 4/11/05 , p. 32. Back |

| 49 |

In 2003 17 textile/clothing/footwear factories were closed, costing 8,000 jobs although the industry still employs around 280,000 workers. DFAT, Submission No 9, p. 16. Back |

| 50 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 16. Back |

| 51 |

180 government-owned companies have been sold off or liquidated. Austrade, Submission No. 5, p. 7. Back |

| 52 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, pp. 16-18. Back |

| 53 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 18. Back |

| 54 |

DFAT, Submission No. 9, p. 5. Back |