74 Questions on notice

- Notice of a question shall be given by a senator signing and delivering it to the Clerk, fairly written, printed, or typed. Notice may be given by one senator on behalf of another.

- The Clerk shall place notices of questions on the Notice Paper in the order in which they are received.

- The reply to a question on notice shall be given by delivering it to the Clerk, a copy shall be supplied to the senator who asked the question, and the publication of the reply is then authorised.

- A senator who has received a copy of a reply pursuant to this standing order may, by leave, immediately after questions without notice, ask the question and have the reply read in the Senate.

- If a minister does not answer a question on notice asked by a senator within 30 days of the asking of that question, or if a question taken on notice during a hearing of a legislative and general purpose standing committee considering estimates remains unanswered 30 days after the day set for answering the question, and a minister does not, within that period, provide to the senator who asked the question an explanation satisfactory to that senator of why an answer has not yet been provided:

- at the conclusion of question time on any day after that period, the senator may ask the relevant minister for such an explanation; and

- the senator may, at the conclusion of the explanation, move without notice – That the Senate take note of the explanation; or

- in the event that the minister does not provide an explanation, the senator may, without notice, move a motion with regard to the minister’s failure to provide either an answer or an explanation.

Amendment history

Adopted: 19 August 1903 as SOs 96 and 97 (corresponding to paragraphs (1) and (2) to (3), respectively)

Amended:

- 11 June 1914, J.79 (clarified the form in which questions on notice could be submitted and allowed for notice to be given by a senator on behalf of another senator)

- [20 August 1975, J.860; re-adopted 18 February 1976, J.24 (sessional order providing for incorporation of questions and answers in Hansard, reading subject to leave)]

- 23 March 1977, J.45 (incorporation of questions and answers in Hansard, reading subject to leave; adopted after trial by sessional order)

- [28 September 1988, J.952 (order of continuing effect allowing remedial action to be taken after a question had remained unanswered for 30 days or longer)]

- 13 February 1997, J.1447 (to take effect 24 February 1997) (incorporation of order of continuing effect allowing remedial action to be taken after a question had remained unanswered for 30 days or longer)

- 8 September 2003, J.2287 (authorisation of the publication of answers on receipt)

- 9 November 2005, J.1380–81 (extending the “30-day rule” to apply to questions on notice at estimates hearings)

- 14 August 2006, J.2474 (to take effect 11 September 2006) (minor wording amendment, consequential on the restructuring of the committee system)

- 27 June 2012, J.2668 (to take effect from first sitting day in 2013) (removing the requirement to print answers in Hansard)

1989 revision: Old SOs 101, 102 and 103 combined into one, restructured as four paragraphs and renumbered as SO 74; language simplified

Commentary

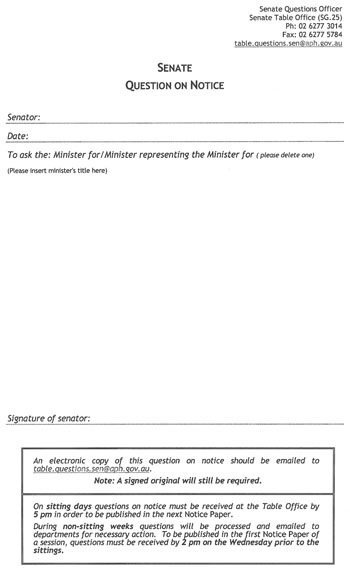

Questions on notice may be lodged using a pro forma. Questions are required to conform with certain rules

Although the purpose of asking questions on notice has remained the same since the adoption of standing orders, the practice of asking questions on notice has changed markedly. It has changed from being an entirely oral practice to being largely a written practice with a remnant capacity for questions and answers to be read aloud, by leave.

In its earliest form, the standing order provided for notice to be given of a senator’s intention to ask a particular question on a sitting day. Such questions would be printed on the Notice Paper in order to give ministers adequate time to consider a full answer.[1] This reflected the practice of various parliaments, including the British House of Commons. In 1931, the House of Representatives adopted standing orders that required questions and answers to be printed in Hansard. This authorised the publication of written answers in Hansard but it also removed the ability of members to ask questions placed on notice and receive the answers orally in the chamber. When adoption of these practices was considered by senators in 1942, the then Clerk of the Senate (John Edwards) observed that “it has always been a tradition in the Senate that business is transacted more deliberately than in the House of Representatives, and for this reason the present practice may be preferred”.[2] Edwards also considered that, due to the numbers of ministers in the House of Representatives as opposed to the Senate, there was more general interest amongst senators in hearing responses. If replies were merely to be printed in Hansard, the situation may arise where members of the press may see replies before senators, a most undesirable outcome. For replies to be printed in Hansard, however, an amendment of standing orders would be necessary to authorise it.

Over time, however, in an effort to use the Senate’s time more efficiently, a practice developed that, on non-broadcast days, senators would rise and read out the number of the question on notice. Only on broadcast days would questions be read in full. In a similar attempt to expedite proceedings, answers to questions were often incorporated, by leave, into Hansard, with answers being read in full only if leave was denied.[3] In August 1968, the Standing Orders Committee began a general examination of the practice of asking and replying to questions on notice, with a particular focus on using time efficiently. During the course of this examination, a senator sought to read a question on notice in full on a non-broadcast day. President McMullin ruled that in light of the established practice senators should ask leave of the Senate to read questions on non-broadcast days.[4] In a 1969 report, the Standing Orders Committee supported the President’s ruling, but noted that should leave be denied for a senator to read a question, a senator could move a suspension of standing orders to address the impediment.[5] On 20 May 1969, the President announced a new practice, whereby senators could indicate which questions they sought to have dealt with orally, and all others would be incorporated into Hansard.[6]

The practice of requiring senators to seek leave to read questions on notice on non-broadcast days was abandoned on the recommendation of the Standing Orders Committee in 1972.[7] The committee noted that leave was never refused and the requirement to seek it was time consuming. The committee maintained support for other current practices and reemphasised that questions and replies ought mostly to be incorporated in Hansard, unless it was considered especially desirable to read them.

On 3 September 1970, Senator Anderson (Lib, NSW) moved the following motion during general business:

That the Senate agrees in principle that the reply to a Question on Notice shall be given by delivering the same to the Clerk. A copy thereof shall be supplied to the Senator who has asked the question and such question and reply shall be printed in Hansard.

Senator Murphy (ALP, NSW) proposed an amendment to require instead that answers be circulated to all senators in the chamber but that they be printed in Hansard nonetheless and not read out. Both the amendment and the original motion were negatived.[8]

It was not long, however, before a further attempt was made towards achieving this goal. In its Third Report for the Fifty–Sixth Session, tabled on 4 December 1974, the Standing Orders Committee recommended that all answers to questions on notice be incorporated into Hansard rather than read in the chamber. Opinion on the recommendation was divided, with a group of senators questioning the impact of the reform on the rights of senators and its overall utility. In particular it was noted that as few senators required answers to be read (estimated by Senator Milliner (ALP, Qld) at one in every 25 answers), minimal time would be saved, and it was therefore an unacceptable infringement upon the rights of senators.[9] Eventually, it was agreed to adopt the changes as sessional orders for a trial period of 6 months.[10] On review of the sessional orders in August 1975, the same concerns being again raised, a compromise was reached allowing senators, by leave, to have answers read. The procedures were adopted as sessional orders at that time, and again at the beginning of the next Parliament until their incorporation into the standing orders on 23 March 1977.[11] By this change, blanket authority was given for the printing of answers in Hansard, a process previously dependent on leave being granted in individual cases or on the answer being read into the record. These are the procedures currently in use, although the reading of answers is now virtually unknown.

Another substantial change occurred in 1988 when, on the motion of Senator Macklin (AD, Qld), a resolution was passed which established what is now known as the “30-day rule” for unanswered questions on notice.[12] The resolution provided for a senator to ask a minister for an explanation if an answer to a question on notice had not been provided after 30 days. It also provided for the senator to then move, without notice, to take note of the minister’s explanation or failure to provide either an answer or an explanation. Debate on such a motion was unrestricted. The resolution was incorporated into standing orders in 1997.[13] From 2 November 1988, a notation was added to the Notice Paper indicating which questions remained unanswered for 30 or more days.

The 30-day rule had other practical implications for the processing of questions on notice. Before its adoption, questions on notice were published in the next Notice Paper after their receipt, becoming known to ministers and departments only through that means. When the rule came into effect, questions received on non-sitting days were forwarded directly to departments to facilitate compliance with the rule. Although such questions continued to be published in the next available Notice Paper, the 30 days were calculated from the day the question was provided to departments.

In the Procedure Committee’s First Report of 2002 the possibility of extending the rule to 60 days was discussed. The rationale behind the suggestion was that many questions on notice require more than 30 days for an adequate response to be prepared and, in any case, senators rarely chose to invoke the remedies available until a period of 60 days had passed. Reservations were expressed about the suggestion, particularly amongst members of the cross bench,[14] while opposition senators requested further consideration of the proposal.[15] The proposal was returned to the Procedure Committee for further consideration but did not resurface.[16] The appropriateness of the rule was confirmed by its extension in 2005 to estimates questions on notice and orders for the production of documents, with the 30 days applying from the date set by committees for the provision of answers and the deadline in the order, respectively.[17]

Apart from the changes to chamber procedure in relation to written questions and answers, there have been changes to the way they are published. Originally, upon receipt, answers to questions on notice were printed in the Journals. In 1917, on a recommendation of the Printing Committee, and apparently in an effort to reflect House of Representatives practice, the printing of answers in the Journals was discontinued.[18] At the same time, the current practice was adopted, by which one copy of an answer is provided to the senator asking the question and another is provided to Hansard. Missing from Senate procedures until 1975, however, was blanket authority for the publication of answers in Hansard. As noted above, publication of individual answers was dependent on their being read into the record or leave being granted for their incorporation.

In the mid–1970s concerns were raised over the increased size of the Notice Paper due to the expanding number of unanswered questions on notice. In its Second Report for the Fifty–Seventh Session, the Standing Orders Committee noted that on the final sitting day in 1976, the Notice Paper comprised 59 pages, of which 35 pages were taken up with questions on notice which had appeared in previous issues and 5 pages with questions appearing for the first time.[19] It recommended that the practice of printing all unanswered questions on notice each day be discontinued and that, instead, on the first sitting day of the week a full Notice Paper be published containing all outstanding questions, but that on subsequent sitting days only new questions be included. The committee’s recommendation was adopted on 16 March 1977.[20] In order for senators to keep track of unanswered questions, a list of questions remaining unanswered is printed in lieu of the questions. Currently, a full Notice Paper, containing the text of all unanswered questions is printed only twice a year, for the first day of the autumn and spring sittings.

In its Second Report of 2003, the Procedure Committee considered a possible gap in the protection given by parliamentary privilege to the process of asking and answering questions on notice. The committee observed that any publication of questions or answers before their appearance in the Notice Paper and Hansard, respectively, would not be protected by privilege.[21] This included publication to the press, for example, before an answer was published in Hansard, a process which could take considerable time depending on the sitting pattern. To ensure protection for the publication of answers it was recommended that the standing orders be amended to authorise the publication of answers as soon as they are received. The amendment was adopted on 8 September 2003.[22]

A minor change to standing order 74(3) removing the requirement to print answers in Hansard was recommended in the Procedure Committee’s First Report of 2012. Historically, answers to questions on notice were printed in Hansard. This practice was mandated by standing order 74 in its earlier form (although answers were authorised for publication when received by the Clerk). This resulted in delays to publication of answers to the general public if the answer was provided in a non-sitting period. If answers awaiting publication were lengthy or numerous, it was necessary for Hansard to stagger publication over several days. Answers are now published in an electronic database linked to the Notice Paper.