58 Business of the Senate

The following business shall be placed on the Notice Paper as business of the Senate, and shall take precedence of government and general business for the day on which it is set down for consideration:

-

A motion for leave of absence to a senator.

-

A motion concerning the qualification of a senator.

-

A motion to disallow, disapprove, or declare void and of no effect any instrument made under the authority of any Act of Parliament which provides for the instrument to be subject to disallowance or disapproval by either House of the Parliament, or subject to a resolution of either House of the Parliament declaring the instrument to be void and of no effect.

-

An order of the day for the presentation of a report from a committee.

-

A motion to refer a matter to a standing committee.

Amendment history

Adopted: 5 October 1922, J.107, as SO 66A. An earlier form giving precedence to disallowance motions was adopted on 24 November 1910, J.228, as SO 115A and continued to operate concurrently

Amended:

- 1 August 1934, J.459–61 (to take effect 1 October 1934) (to add disapproval of awards made under an Act and subject to disallowance by either House to the catalogue of items to be dealt with as business of the Senate)

- 16 August 1978, J.303–04 (to clarify the intended scope of paragraph (c) to apply to motions to disallow all instruments subject to disallowance or disapproval)

1989 revision: Old SOs 66A and 119 combined and renumbered as SO 58; language simplified; paragraph (e) duplicated from SO 25 in relation to references to legislative and general purpose standing committees and broadened to apply to references to all standing committees

Commentary

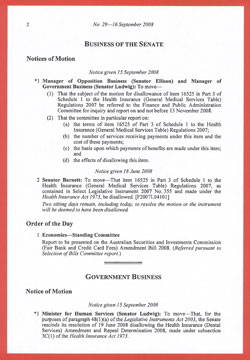

Senator Anthony St Ledger (Anti-Socialist, Qld) whose motion to disapprove certain Census questions led to the concept of business of th Senate (Source: National Library of Australia)

Business of the Senate items are listed ahead of Government Business in the Notice Paper

Standing order 58 creates a category of business known as business of the Senate which takes precedence over government and general business. Unlike government or general business, business of the Senate is determined by the subject matter of the motion or order of the day, not by the status of the mover. Five matters, as listed in paragraphs (a) to (e), are now designated as business of the Senate, but the Senate may also decide to treat other matters as business of the Senate from time to time to afford those matters the special precedence available under this standing order.[1]

The concept that there are types of business which are so important to the Senate as a whole that they warrant special precedence above the business of the executive government is of great significance to the evolution of the Senate as an independent parliamentary institution. The need for a standing order to reflect this concept was revealed during debate on a motion to disapprove parts of the Census Regulations in 1910. Certain proposed questions in the upcoming census, relating to a person’s wages or salary, hours of work, cash in hand on census night and whether they were a “total abstainer from alcoholic beverages” were disapproved by the Senate on the motion of Senator St. Ledger (Anti-Soc, Qld), a backbencher. His private (later general) business motion was moved on 4 November 1910 and debate had not concluded before the Senate adjourned for the week.[2] When debate resumed a week later, there had clearly been some consternation about the fate of this private business order of the day, as expressed by the first speaker in the resumed debate, the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, Senator Millen (Anti-Soc, NSW):

Since Friday last it has been made manifest to honourable senators, at any rate it has been brought home to myself, that the standing order under which we proceed to discuss statutory regulations is so faulty that it might as well be out of the code. The Standing Orders leave a motion of this description to the mere chance as to whether or not the Government is prepared to afford an opportunity for its consideration. We can discuss this matter quite free from any party feeling, or even personal feeling, because in this case the Minister has done the right thing and agreed to furnish us with an opportunity to express out views. But I submit there can be no sense or force in a provision that the regulations made under a law shall have force and effect, provided that either House of the Parliament does not dissent therefrom within a certain period, unless our inherent right is respected. Pressure of circumstances may crowd out the opportunity which it is clearly intended by law that we should enjoy. I think that the Standing Orders Committee should be asked to revise the standing order, so as to insure that a motion of this kind shall by right become the business of the Senate, and that an opportunity for discussing it shall be provided by the forms of the Senate. … It ought to be the business of the Senate, and not the business of the Government.[3]

The following week, Senator St. Ledger’s colleague, Senator Chataway (Anti-Soc, Qld), moved a motion instructing the Standing Orders Committee “to consider the desirability of submitting a Standing Order, for the approval of the Senate, providing that any motion disapproving of a regulation shall be regarded as business of the Senate and shall take precedence of Government Business or Private Business”.[4] President Givens presented the Standing Orders Committee’s report on 24 November 1910 recommending the adoption of such a standing order. A motion to adopt the report was moved immediately by the Government, by leave, and agreed to without debate. Standing order 115A – “A motion disallowing a regulation shall take precedence of Government and Private Business” – thus came into being as the precursor to SO 58, but without mentioning the term “business of the Senate” which had been used both by Senator Millen in calling for such a category, and by Senator Chataway in his notice of motion.

The situation was rectified in 1922 when the Senate adopted SO 66A which defined the new category of business of the Senate, including disallowance motions already covered in SO 115A. For such a significant new standing order, the lack of discussion on the public record is unfortunate. There were no obvious “trigger” debates as there had been for SO 115A. There is no record of discussion in the minutes or report of the Standing Orders Committee and no debate of substance on the report before it was adopted.[5] We cannot be certain what prompted the Senate to revisit the concept of business of the Senate or why it selected those particular matters covered by paragraphs (a), (b) and (d) for inclusion, but we may speculate that diligent clerks, led by G.H. Monahan, combed the standing orders and volumes of Presidents’ rulings to collect matters that were either afforded precedence or had warranted priority treatment in the past and might therefore be candidates for the new category of business. As well as noting that SO 47 provided for a motion for leave of absence for a senator to have priority over other motions, they may have put forward the following rulings, some more tentatively than others:

President Baker – A motion for leave of absence to a Senator may be dealt with prior to the adoption of the Address-in-Reply. (9 March 1904, SD, p.288; 10 March 1904, SD, p.353)

President Gould – The consideration of a report from the [Standing Orders] Committee is not “Government Business”; but it has been the invariable custom for the Government to take charge of the Order of the Day. (6 August 1909, SD, p.2147)

President Gould – A decision to take a motion which concerns the business of the Senate overrules a sessional order giving precedence to certain business. (21 October 1909, SD, p.4818)

President Gould – A motion relative to an inquiry being conducted by a Select Committee concerns the business of the Senate, and therefore should take precedence of other matters on the notice-paper. (25 November 1909, SD, pp.6314–15)

President Givens – A motion touching the qualification of a Senator comes within the category of business of the Senate, which has always been accorded priority. (14 March 1917, SD, p.11318)

Apart from the ruling on motions for committee inquiries,[6] there is a clear link between rulings such as these and the components of old SO 66A, as proposed and adopted in 1922. The question of motions for the reference of matters to committees would be dealt with in the context of the legislative and general purpose standing committees in 1970.

Subsequent amendments to the standing order in 1934 and 1978 focused on defining the scope of the motions to be treated as disallowance motions to ensure consistency of treatment.[7]

The 1989 revision resolved an issue that had arisen in the formulation of the sessional orders establishing the legislative and general purpose standing committees in 1970, now provided for in SO 25. As noted by Edwards in the 1938 MS, business of the Senate which is adjourned from day to day retains its right of precedence. This seems an unexceptionable rule: certain business, whether in the form of a motion or an order of the day, has precedence till finalised. There was a built-in safeguard against such business dominating the agenda because under old SO 127, orders of the day were required to be called on two hours after the time fixed for the meeting of the Senate. Any unfinished debate on motions was automatically interrupted and the Senate could then decide whether it wished to postpone orders of the day and continue with the interrupted motion, or deal with the orders of the day and come back to motions later. Edwards notes that the usual practice was to postpone orders of the day until the disallowance motion had been disposed of, but there were also precedents for the Senate proceeding to orders of the day when a disallowance motion had been interrupted.[8]

The issue in 1970 was the mechanism for referring matters to the legislative and general purpose standing committees, dealt with in a supplementary resolution moved by the Leader of the Government in the Senate, Senator Anderson (Lib, NSW), on 19 August 1970.[9] The existing procedure for referring bills by motion without notice immediately after the second reading was considered satisfactory, but there was some concern that the reference of other matters could be sprung on the Senate by way of amendment of a relevant motion. References made by amendments to motions would not be permitted.[10] The chosen method was by motion after notice and such notices were to be treated as business of the Senate. As Senator Anderson informed the Senate, the proposed resolution provided protection:

… in that, notice having been given, the matter must come on and have priority on the next day of sitting, so that it can never be said that the Government or some group in the Senate is seeking to kill a notice of motion simply by not bringing it on.

There is 1 other point that I feel bound to make clear. Paragraph (11) [of the proposed resolution] gives precedence to notices for references to committees. However, if such a motion was not disposed of 2 hours after the time fixed for the meeting of the Senate, the debate would be interrupted under standing order 127. Then the resumption of the debate would not have precedence subsequently; it would be an order of the day in the usual way. I know that tends to weaken what I have said about putting in a safety valve. I have discovered that because of standing order 127 the safety valve perhaps is not as strong as it should be. … But I am perfectly willing to find some form of words that will knock that difficulty out of the way so that the position can be quite clear and positive.[11] (emphasis added)

In other words, a notice of motion to refer a matter to a committee had precedence, but if the motion was not resolved at the time of moving and debate was interrupted, the order of the day for the resumption of the debate, on the same matter, did not have precedence. This was not an unintended interpretation, as Senator Anderson’s rather apologetic explanation of it confirms, and it was duly written up in the 4th and 5th editions of Australian Senate Practice with the explanation that precedence as business of the Senate applied only to the day when the motion was moved.[12] It was, however, an unnecessarily restrictive and cautious interpretation that was able to be addressed by the 1989 revision by including in SO 58 the final paragraph, “a motion to refer a matter to a standing committee.” By not confining precedence to the notice of motion, the unusual and inconsistent interpretation prevailing before the revision was able to be discarded. Moreover, one source of previous difficulties, old SO 127, was deleted as it had become obsolete, partly because of the large amount of business now on the Notice Paper but also because of the adoption of a more detailed routine of business that provided specific opportunities for dealing with a variety of business. The 1989 revision also had the effect of allowing motions to refer matters to all standing committees to be dealt with as business of the Senate, not just references to legislative and general purpose standing committees.