Chapter 2

Prevalence of mental ill-health

Introduction

2.1

This chapter considers the extent and significance of mental ill-health

in Australian Defence Force (ADF) members, veterans, and the families of ADF

members and veterans.

Healthy soldier effect

2.2

When considering any occupational health study (and especially studies

of military populations) it is important to note the 'healthy worker effect', in

which people who are employed exhibit a lower mortality rate than the general

population. This effect is often primarily attributed to a selection bias

whereby people who are employed are, on average, healthier than the general

population, which includes people who are severely ill or disabled and

therefore unable to work. Military populations are, on average, far healthier

than other employed populations, which are in turn healthier than the general

population. The 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and Wellbeing Study (MHPW

study) noted that:

The 'healthy worker effect' comes from the fact that, during

recruitment, the ADF takes steps not to enlist individuals with pre-existing

disorders. It then provides quality and accessible health services to all of

its members. In addition, there is an occupational health service in the ADF

that provides quality care at no cost to ADF members and, following deployment,

ADF members are extensively screened to ensure they receive treatment if they

need it. The ADF workforce should, therefore, be healthier than the general

community.[1]

2.3

Some occupational health studies of military cohorts refer to this as

the 'healthy solider effect'.[2]

A number of submissions highlighted the importance of acknowledging the

'healthy solider effect' when considering the prevalence of mental disorders

for current and former ADF personnel.[3]

The Australian Families of the Military Research and Support Foundation (AFOM)

asserted that 'research done in this area, which does not provide for the

Healthy Soldier Effect (HSE) does not reflect the true extent and significance

of the issues' and called for all future research to take the effect into

account.[4]

Prevalence of mental ill-health in the Australian Defence Force

2.4

The MHPW study was the first comprehensive investigation of the mental

health of an ADF serving population. The study examined the prevalence rates of

the most common mental disorders, the optimal cut-offs for relevant mental

health measures, and the impact of occupational stress factors. Nearly 49 per

cent of ADF members serving during the time of the study (April 2010 to January

2011) participated.[5]

2.5

The MHPW study obtained normative mental health data from the Australian

Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in order to interpret and fully understand the rates

of mental disorders reported in the ADF. The ABS data, derived from the 2007

ABS National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, was adjusted to match the

demographic characteristics of the current ADF serving population (for age,

sex, and employment status).[6]

2.6

The study found that more than half of the ADF population had

experienced a mental disorder in their lifetime, a significantly higher rate

than experienced by the general Australian population. The study noted that

'this level of mental illness in the ADF suggests that, despite the fact that

the ADF is a selected and trained population that generally has better access

to health care (the 'healthy worker effect'), this population is affected by a

range of stress factors caused by the nature of their work'.[7]

Prevalence of mental disorders

2.7

The MHPW study found that 22 per cent of the ADF population (11,016) had

experienced a mental disorder in the previous 12 months and that approximately

6.8 per cent (760) of those who had experienced a mental disorder had

experienced more than one mental disorder at a time. The MHPW study noted that

while the prevalence of mental health disorders in the previous 12 months was

similar to the general Australian population sample, the profiles of specific

disorders in the ADF varied.[8]

Table 2.1 provides the estimated prevalence of lifetime and 12-month mental

disorders in the ADF and compares this to the ABS sample matched by age, sex,

and employment status.

Table 2.1–Estimated prevalence of

lifetime and 12-month disorders

|

|

Lifetime prevalence

|

12-month prevalence

|

|

|

ABS %

|

ADF %

|

ABS %

|

ADF %

|

|

Any affective disorder

|

14.0

|

20.8*

|

5.9

|

9.5*

|

|

Any anxiety disorder

|

23.1

|

27.0

|

12.6

|

14.8

|

|

Any alcohol disorder

|

32.9

|

35.7

|

8.3

|

5.2*

|

|

Any mental disorder

|

49.3

|

54.1*

|

20.7

|

22.0

|

* Significantly different

from the ABS study.

Department of Defence, Mental

Health in the Australian Defence Force: 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and

Wellbeing Study Report, p. xv.

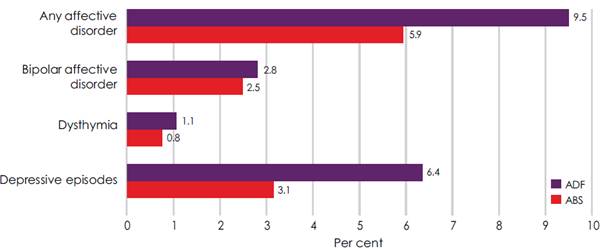

2.8

The MHPW study found that the most significant difference between the

ADF population and the general Australia population sample was the prevalence

of affective disorders (also known as mood disorders) (See Figure 2.1). It

found that depressive episodes in both male (6.0 per cent) and female (8.7 per

cent) ADF members were significantly higher than the general community rates

(2.9 per cent and 4.4 percent respectively). There were no significant

differences, however, between ADF males and ADF females in the prevalence of

affective disorders.[9]

Figure 2.1–Estimated prevalence of

12-month affective disorders, ADF and ABS data

Department of Defence, Mental

Health in the Australian Defence Force: 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and

Wellbeing Study Report, p. xix.

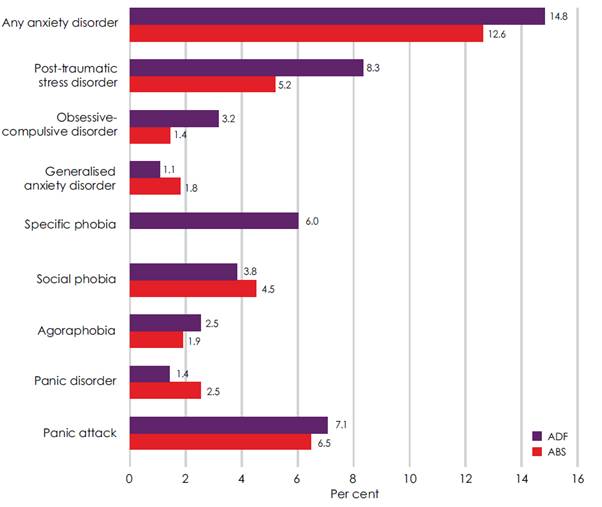

2.9

The MHPW study found that the most common mental disorders in the ADF

were anxiety disorders, with the most prevalent anxiety disorder being

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (see Figure 2.2). The overall prevalence

of anxiety disorders was not found to be significantly higher than in the general

Australian population. The primary difference between the ADF and the general

Australian population was the significantly higher rates of PTSD in ADF males

(8.1 per cent compared to 4.6 per cent) and the significantly lower rates of

panic disorder in the ADF (1.2 per cent compared with 2.5 per cent). The study

noted that, as is the case in the general Australian population, female ADF

personnel rated higher than male ADF members on anxiety disorders and were

significantly more likely to have panic attacks or panic disorder.[10]

Figure 2.2–Estimated prevalence of

12-month anxiety disorders, ADF and ABS data

Department of Defence, Mental

Health in the Australian Defence Force: 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and

Wellbeing Study Report, p. xix.

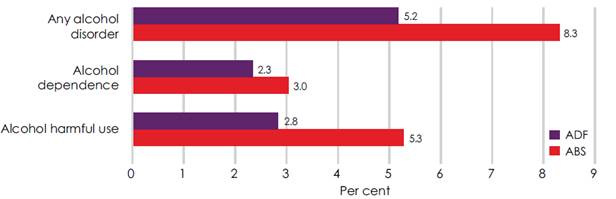

2.10

The MHPW study also found that both male (3.1 per cent) and female (1.3

per cent) ADF members had significantly lower rates of alcohol harmful use

disorder compared to the general Australian population (5.5 per cent and 3.7

per cent respectively) (See Figure 2.3). ADF females were significantly less

likely to have an alcohol disorder than ADF males.[11]

Figure 2.3–Estimated prevalence of

12-month alcohol disorders, ADF and ABS data

Department of Defence, Mental

Health in the Australian Defence Force: 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and

Wellbeing Study Report, p. xx.

Future research

2.11

The Departments of Defence and Veterans' Affairs are currently funding

the largest and most comprehensive study undertaken in Australia to examine the

impact of military service on the mental, physical and social health of serving

and ex-serving ADF personnel and their families. The Transition and Wellbeing

Research Programme, led by the Centre for Traumatic Stress Studies (CTSS) at

the University of Adelaide, consists of three studies: the Mental Health and

Wellbeing Transition Study, the Impact of Combat Study, and the Family

Wellbeing Study.[12]

2.12

The Mental Health and Wellbeing Transition Study will:

-

determine the prevalence of mental disorders amongst personnel

who have transitioned from full-time service between 2010 and 2014;

-

examine the physical health status of serving and ex-serving

personnel;

-

investigate pathways to care for serving and ex-serving

personnel, with a priority on those with a diagnosed mental disorder;

-

examine factors that contribute to the current wellbeing of

serving and ex-serving personnel;

-

investigate how mental health issues change over time, especially

once an individual transitions from full time service;

-

investigate technology and its utility for health and mental

health programs, including implications for future health service delivery; and

-

investigate the mental health and wellbeing of current serving

reservists.[13]

2.13

The research program will survey a cohort of approximately 24,000

transitioned service personnel, together with current serving personnel and

reservists (drawing from the Military and Veteran Research Study Roll)[14]

for the Mental Health and Wellbeing Transition Study and the Impact of Combat

Study. The Family Wellbeing Study is being conducted by the Australian Institute

of Family Studies and will survey family members nominated by the participants

of the other two studies.[15]

2.14

The research program is also actively following up with all participants

of the 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and Wellbeing Study Report as well

as participants of the Middle East Areas of Operations (MEAO) Census Health

Study. This will allow the research program to conduct both a prevalence

study and a longitudinal follow up.[16]

2.15

Prior to its closing in December 2014, the Centre for Australian

Military and Veterans' Health conducted epidemiological studies that provide a

comprehensive picture of the health of serving members, veterans, and their

families following specific deployments including:

-

Rwanda Deployment Health Study (2014);

-

Middle East Area of Operations (MEAO) Health Study – Mortality

and Cancer Incidence Study (2013);

-

Middle East Area of Operations (MEAO) Health Study – Census Study

(2012);

-

Middle East Area of Operations (MEAO) Health Study – Prospective

Study (2012);

-

Timor-Leste Family Study (2012);

-

Bougainville Health Study (2009);

-

East Timor Health Study (2009); and

-

Solomon Islands Health Study (2009).[17]

Linking research to policy

2.16

Dr Annabel McGuire noted that whilst research studies have added to the

fundamental scientific understanding of the impact of military service on ADF

personnel and their families, 'the biggest flaw in this work was that the

Departments and the research teams failed to work together to translate the

findings into actionable policy and programs' and that the research was

generally not well received by the broader Defence community:

In general terms, the research has not been well received by

the broader Defence community, in part because scientific reports do not tell

people's story: reading that eight percent of the Defence Force has screened

positive for PTSD in the past year does not feel right when you look around and

can see four guys in your section are struggling. The answer to this problem is

not to commission new and bigger research projects aiming to be the panacea for

the failings of previous research. The disenfranchised ex-service community

does not respond well to another survey from which they see no outcome.

Research must be explicitly and overtly linked to changes in policy and/or practice.[18]

Heightened risk factors of service

2.17

The Chief of the Defence Force, Air Chief Marshal Mark Binskin AC, told

the committee that Defence 'acknowledge[s] that military service creates unique

stresses'[19].

DVA explained that the 'day to day stressors of military service can include

significant periods away from home, family and friends while on posting and

reduced access to social and family supports, including the impact on spouses

and children'.[20]

Impact of deployment on mental

health

2.18

As at January 2011, approximately half of all ADF personnel have been

deployed multiple times. In the MHPW study, 43 per cent of ADF personnel

participating reported being deployed multiple times, 19 per cent reporting

being deployed once and 39 per cent never having been deployed.[21]

Every year, approximately 12,000 ADF personnel are in the 'operational

deployment cycle', meaning that they are preparing, deploying or transitioning

home.[22]

2.19

Between July 2013 and June 2014, 896 ADF personnel were referred to the

ADF Rehabilitation Program with a primary diagnosis of a mental health

disorder. Of these, 33.6 per cent were identified as being 'deployment

related'. In this period, 206 of the 896 personnel were referred with a

specific diagnosis of PTSD, of which 84 per cent were identified as being

'deployment related'. Since 2000, 108 ADF personnel are suspected or confirmed

to have died as a result of suicide, of which 47 had previously deployed.[23]

2.20

The findings of the MHPW study indicated that there was no significant

link between deployment and an increased risk of developing PTSD, anxiety,

depression or substance abuse disorders, stating that 'deployed personnel did

not report greater rates of mental disorder than those who had not been

deployed'.[24]

However, the Chief of the Defence Force acknowledged that the risk of

experiencing a traumatic event increases during deployment and that exposure to

trauma increases the risk of poor mental health outcomes:

Our research clearly shows that exposure to trauma increases

a person's risk of developing a mental health condition or problem, as you

would expect. Some people will be exposed to trauma while on operations. Others

may experience traumatic events outside a deployment or military service.

Despite reports to the contrary, we fully accept that the risk of experiencing

a traumatic event increases during a deployment whether it be to a conflict

zone, during a humanitarian or disaster relief mission or in border protection

operations.[25]

2.21

Defence advised that for the majority of ADF members who have been

deployed on a warlike operation (81.7 per cent), their cumulative time on a

warlike operation equates to one year or less (see Table 2.2).

Table 2.2–Cumulative time on a

warlike operation

|

Time

|

1 year or less

|

Between 1 and 2 years

|

Between 2 and 3 years

|

More than 3 years

|

|

ADF members

|

40,959

(81.7 per cent)

|

8,367

(16.7 per cent)

|

737

(1.5 per cent)

|

56

(0.1 per cent)

|

Department of Defence, answer

to question on notice, 2 June 2015 (received 15 July 2015.

Exposure to traumatic events

2.22

The Australian Psychological Society noted that 'it is well known that

the unique occupational risks of ADF service include significant exposure to

potentially traumatic events'.[26]

The MHPW study agreed, noting that:

...members of the ADF are at risk of developing mental

disorders, as they are exposed to a range of occupational stressors – for

example, exposure to traumatic events and extended periods of time away from

their primary social support networks.[27]

2.23

Defence reported that the most common potentially traumatic event

reported by deployed personnel in the Return to Australia Psychological

Screening in Annual Mental Health Surveillance Reports has consistently been

'in danger of being injured', followed by 'in danger of being killed'. Defence

noted that this was different for Navy personnel deployed on Operation Resolute,

who reported in the Mental Health and Wellbeing Questionnaire that the most

common exposure was 'witnessed human degradation/misery on a large scale'

followed by 'in danger of being injured'.[28]

2.24

In addition to considering the number of traumatic experiences, the MEAO

report also considered the types of traumatic combat-related experiences

associated with PTSD symptoms. The MEAO study found that participants who

reported experiencing five or more types of traumatic exposure were

statistically significantly more likely to have adverse psychological health

outcomes.[29]

The MEAO study found that exposures such as 'threatening situation and unable

to respond', 'handling/seeing dead bodies', and 'being witness to human

degradation and misery' were strongly and statistically associated with PTSD

symptoms.[30]

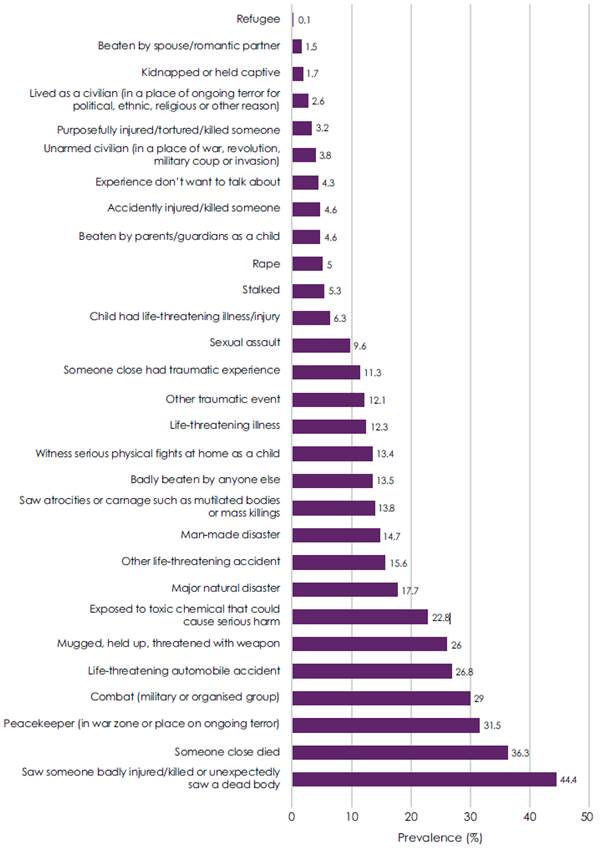

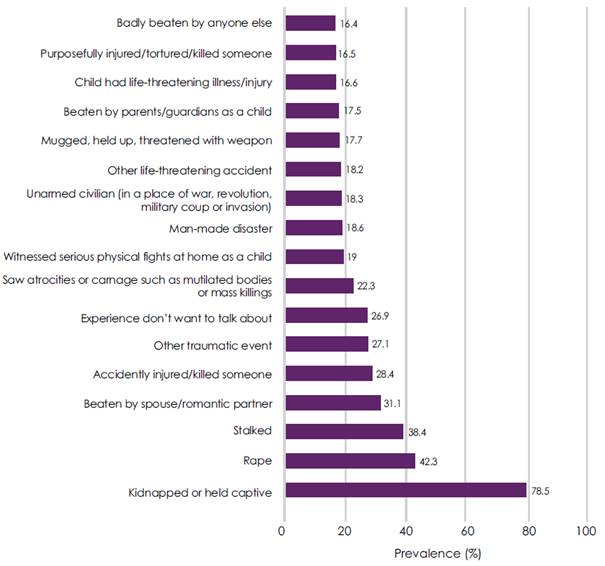

2.25

The MHWP study also considered the proportion of those personnel exposed

to traumatic events that go on to develop PTSD (see Figure 2.5). The event associated

with the highest rates of PTSD was 'being kidnapped or held hostage', with 78.5

per cent of those who had experienced this event having PTSD. Other events that

were associated with very high rates of PTSD were rape (42.3 per cent), being

stalked (38.4 per cent), and domestic violence (31.1 per cent). The rate of

PTSD for serving as a peacekeeper (9.2 per cent) and combat experience alone

(10.4 per cent) were comparatively quite low. The

MHWP study commented that:

In summary, these results provide an insight into the fact

that certain aspects of military service such as combat or peacekeeping do not

per se present major risks to post-traumatic stress disorder. Rather, it is

likely that there are certain experiences within military service, such as seeing

atrocities or accidently injuring or killing another individual, which may be

particularly damaging to an individual's psychological health.[31]

2.26

DVA advised the committee that in addition to the risk of exposure to

potentially traumatic experiences during deployment, ADF members may also be

exposed to potentially traumatic experiences during peacetime service

activities, for example during disaster assistance or as a result of serious

training accidents:

Any military service involves risk of exposure to traumatic

experiences, such as trauma arising from disaster assistance or serious

training accidents. For instance, in 1996 two Black Hawk helicopters collided

and crashed at the High Range Training Area near Townsville, resulting in the

deaths of 18 personnel and injuries to a further 12 personnel. In 2005, a Sea

King helicopter crashed on Nias Island in Indonesia while on a humanitarian

support mission, with the deaths of 9 ADF personnel.[32]

2.27

The MHWP study commented on the difficulty of clearly differentiating

between traumas experienced during ADF service and traumas experienced in ADF

members' private lives, noting that for clear conclusions to be drawn regarding

the impact of ADF service 'traumas experienced during military service and in

the private lives of ADF members need to be separated'.[33]

Figure 2.4–Estimated prevalence of

lifetime trauma exposure in the ADF

Department of Defence, Mental

Health in the Australian Defence Force: 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and

Wellbeing Study Report, p. 49.

Figure 2.5–Estimated prevalence of

post-traumatic stress disorder from specific event types

Department of

Defence, Mental Health in the Australian Defence Force: 2010 ADF Mental

Health Prevalence and Wellbeing Study Report, p. 50.

2.28

The committee received powerful evidence from veterans who described

the traumatic experiences that they were exposed to during their service and

the impact that it has had on their mental health. Slater & Gordon gave

numerous examples of clients' traumatic experiences on deployment. A veteran

solider and combat first-aider who was deployed to Afghanistan and suffers from

chronic PTSD stated:

I was a scout in my section and we were doing a cordon and

research mission. I was providing security when the IED went off...I first came

across Private [name omitted] who had his leg blown off, he had a tourniquet on

and was being treated; I was stunned for a split second. People were screaming

and shouting. I then realised my friend [name omitted] had been killed. There

were bits of his body, his body armour and kit strewn across the field. There

was a child that had his toes blown off from the blast that had begun running

away from us at that point. There were three Afghan civilians lying on the

ground who had major blast injuries and who I commenced treating. After the

first helicopter took the Private away and the second helicopter took the

civilians, the last helicopter came to get the last casualty and my friend's

body. As I loaded the last casualty onto the helicopter it hit me when I saw

his name written across his body bag, my heart sank as the realisation of what

happened set in. The helicopter took off and my sergeant asked me to help him

pick up some body parts that had been forgotten in the chaos.[34]

2.29

The following was conveyed by Slater & Gordon Lawyers from a

returned servicemen of the East Timor Peacekeeping Mission suffering PTSD and

depressive symptoms and who attempted suicide during deployment:

During my deployment there we were also stopped by distressed

locals during one of our patrols. The Timorese led our patrol section to a

burnt out building...towards the back of the building in one of the rooms, there

was a local woman. The woman was deceased and surrounding her was an evident

smell of fuel. I drew my own conclusion that she appeared to have been doused

with petrol, set alight and shot in the head. We carried her outside and once

in the open, I could see the poor woman was a mother.

Fused to her was the baby that she must have been holding at

the time of her execution...I see this woman and her child whilst sleeping and

often for no reason start to think of her during my day to day goings on. I

feel ashamed that I was not there fast enough to stop what happened. I feel

angry that a helpless woman and her baby were killed in such an inhumane

manner. I cannot seem to shake what happened to her and feel immense anger at

how an innocent child was burnt (most possibly whilst it was still alive). I am

haunted by this and often find myself getting teary. It just doesn't go away.[35]

2.30

Mr Matthew McKeever told the committee of his repeated exposure to

highly traumatic situations across five deployments during his 16 years of

service:

I killed my first person on 30 August 2010—retrieved the

body; you are required to fingerprint it and required to iris scan. I was

offered no mental support after that. I then had dealings with other dead

Taliban who were killed by other people where I was required to physically examine

them for bullet holes. On occasion when I would lift their arms up my fingers

would go through their wrists from the bullet holes. Because of that, I have no

sexual function. I have to inject myself with a needle; I can show you it. If I try to have sexual intercourse with my partner, I get

flashbacks from my fingers going into dead people. So I have to inject my penis

with a needle of the size I am showing you—it is quite large—which is not nice.

So I have no sexual life, and I have not slept with my wife for over 12 months

due to severe nightmares.

My second deployment to Afghanistan was totally different. My

first one was high activity with numerous contacts, numerous IED explosions and

handling numerous dead bodies. My second one was quite different. I knew I had

a problem, but then I was exposed to the handling of dead children. In one

instance with one child, I had to pick the little boy up by his ankles and

shake him to prove to his parents that he was deceased. Then when I returned

from Afghanistan I tried to commit suicide because I saw my child and that

brought back a lot of memories.[36]

2.31

Mr McKeever acknowledged that the risk of exposure to traumatic

experiences is inherent to deployment as an infantry solider but asserted that

the risk is poorly managed. Mr McKeever pointed to policies that increased

exposure to potentially traumatic experiences for soldiers who must 'process'

(iris and finger print scan) the human remains of those they have killed. Mr

McKeever called for specialised teams of medical officers to process human

remains to minimise this risk:

I know what an infantry soldier does. But there should be

people in specialised areas, as they had in East Timor and other places, so

that when you kill somebody and they have to be dragged out and processed,

there is a specialist team that comes out and does that—medical officers. I

told my soldiers, 'If you do not have to see the dead body, don't see it.'[37]

2.32

Defence advised the committee that the collection of biometric

information, as referred to by Mr McKeever, is authorised by and must comply

with Defence Instructions (General) Operations 13-16 which states, 'biometric

samples, including collection by invasive techniques, may be taken from human

remains but only if this can be done without mutilating or otherwise

maltreating the remains. The utmost respect is to be shown to human remains at

all times'. Defence noted that the approach and manner in which ADF members'

process human remains is shaped by the requirements of the operation as well as

the operational environment and tactical situation.[38]

Defence's policies regarding operational mental health and psychology support

in the pre-deployment, deployment, and post-deployment phases are discussed in

Chapter 3 of this report.

Abuse

2.33

The ADF has had a long history of incidents of reported abuse and

harassment (including sexual abuse) within its ranks. The Senate Foreign

Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee has previously conducted

inquiries which have addressed, or touched upon, abuse and sexual harassment in

Defence. These inquiries have included:

-

Processes to support victims of abuse in Defence (October 2014);

-

Report of the review of allegations of sexual and other abuse in

Defence, conducted by DLA Piper, and the response of the government to the

report (June 2013);

-

Inquiry into an equity and diversity health check in the Royal

Australian Navy – HMAS Success (September 2011);

-

The Effectiveness of Australia's military justice system (June

2005); and

-

Sexual Harassment in the Australian Defence Force (August 1994).[39]

2.34

A number of submissions commented negatively on 'ADF culture' and detailed

members' and veterans' personal accounts of abuse in the ADF and its effect on

mental health.[40]

Mr Ciaran Hemmings told the committee of his experience of abuse following a

physical injury and its impact on his mental health:

I have done six years in Defence. I did not deploy. I

sustained my injury whilst on rifle combat at Butterworth over in Malaysia on a

training exercise. I crushed my right arm whilst over there. Mental health

within Defence is—like [Mr McKeever] said, they do not care at the end of the

day. The names you get called—I have got a body suit because I have got severe

nerve pain. I also suffer from adjustment disorder with anxiety and depression.

And in the pack mentality of Defence that does not sit well, as [Mr McKeever]

said, and probably the others. As soon as you are injured, you are like a

dog—you are kicked out of the pack and there is no way of getting back into

that pack. I was injured in 2013. I tried my hardest to get better, but the

ridicule within Defence was phenomenal. Every time I tried to do something it

would be like, 'Don't do that—you might hurt your other hand' or 'Come on,

Michael Jackson, give us a moonwalk'. It is shocking. It just makes the

mentality worse. You can speak to hierarchy about it and you get ridiculed

also, like officers and so forth. You get to the point where you fear to even

speak up...It just came to the point where I had to go to the doctor on base

myself and ask for help because I was the same: I was at the point where I

would sit at home at night and think about suicide. It got really hard, to the

point where—I have got three children—it come down to being there for my kids.

I could not do this without help and seeing [Dr Niall McLaren, psychiatrist].

The way work treated you—I hated going to work. I would sit at the back gate

and struggle for half an hour to even drive into that place knowing that as

soon as you did you would just get ridiculed and picked on for your condition.

It is massive in Defence and it is not

looked at at all. I spoke up to mates, and stuff like that, and they would just

say, 'Harden up, princess. It's not that bad.' But once you have got an injury

and you are kicked out of the pack, and because you have got your brethren and

your mates and stuff, the next minute you are pushed off to the side,

literally. They will grab you and they will sit you in another building away

from all the non-injured personnel. That is where you sit until you are kicked

out.[41]

2.35

Although not the subject of this inquiry, it is important to acknowledge

the enormous impact that harassment, bullying, and abuse (sexual and otherwise)

may have on the mental health of both the subject of harassment, bullying, and

abuse as well as witnesses. Chapter 5 of this report will consider the stigma

associated with mental ill-health and its impact in greater detail.

Prevalence of mental health disorders in veterans

2.36

The Department of Veterans' Affairs (DVA) informed the committee that as

at March 2015, it was supporting 147,318 veterans with one or more disabilities

accepted by DVA and of these, 49,668 veterans had one or more accepted mental

health disabilities (See Table 2.3). DVA advised the committee that there are

two pathways by which veterans may apply to DVA:

-

the liability pathway: if they have mental health conditions

related to service in the ADF, in order to receive compensation and treatment;

and

-

the non-liability pathway: if they have certain mental health

conditions whatever the cause, in order to receive treatment only.

Table 2.3–Veterans with mental

health conditions accepted by DVA, March 2015*

|

Number of veterans with

|

Related to service

(liability)

|

For any cause

(non-liability)

|

Net total

|

|

One or more accepted

disabilities

|

143,652

|

34,451

|

147,318

|

|

One or more accepted

mental health disabilities

|

45,953

|

15,526

|

49,668

|

|

PTSD and other stress

disorders

|

28,875

|

11,705

|

31,501

|

|

Depression or dysthymia

|

11,649

|

4,102

|

13,976

|

|

Alcohol and other

substance use disorders

|

13,273

|

322

|

13,532

|

|

Anxiety

|

10,406

|

2,214

|

11,932

|

|

Adjustment disorder

|

1,911

|

N/A

|

1,911

|

* Note: This table is a count

of claims. Some individuals are counted multiple times.

Department of Veterans'

Affairs, Submission 35, p. 12.

2.37

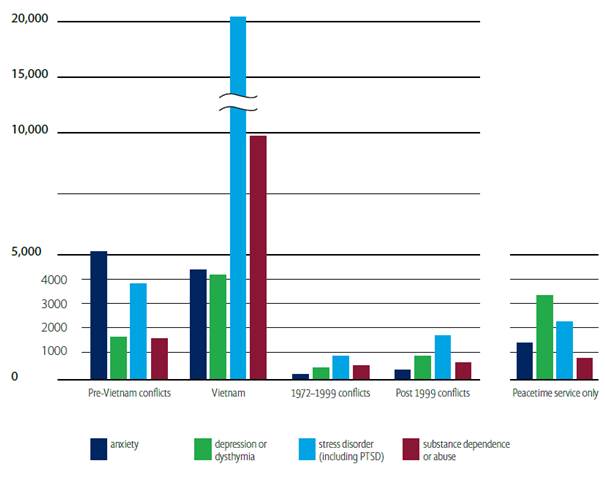

Figure 2.6 sets out the top mental health conditions, as at March 2013,

grouped into conflict cohorts.

Figure 2.6–Top mental health

conditions as at March 2013, includes VEA, MRCA &SRCA

Department of Veterans'

Affairs, Veteran Mental Health Strategy: A Ten Year Framework 2013-2023,

p. 28.

2.38

Table 2.4 shows the number mental health claims accepted by DVA each

year over the past decade; a rate of between 3,100 and 5,350 claims per year.

Table 2.4–Flow of accepted mental

health claims accepted by DVA, January 2015

|

|

2004

|

2005

|

2006

|

2007

|

2008

|

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

|

Related to service (liability)

|

4,185

|

3,764

|

3,160

|

3,197

|

2,928

|

2,779

|

2,458

|

2,332

|

2,748

|

3,412

|

3,579

|

|

For any cause (non-liability)

|

1,158

|

1,228

|

1,146

|

819

|

841

|

880

|

786

|

758

|

956

|

1,149

|

1,680

|

|

Net total

|

5,343

|

4,992

|

4,306

|

4,016

|

3,769

|

3,659

|

3,244

|

3,090

|

3,704

|

4,561

|

5,259

|

* Note: some veterans are

counted multiple times if they have more than one condition.

Department of Veterans'

Affairs, Submission 35, p. 12.

2.39

The Returned & Services League of Australia (RSL) questioned the

numbers provided by DVA, asserting that the potential number of veterans with

service-related mental health problems could be significantly higher, noting

that it is estimated that only one in five veterans have DVA client numbers:

Senator Michael Ronaldson, Minister for Veterans' Affairs,

reports that DVA clients number approximately one in five of all Australians

who have service in the ADF. Using DVA's approximate current client numbers of

330,000, this means that the potential number of veterans suffering

service-related mental ill-health could be significantly higher than those who

have lodged claims.

As ex-serving members are not compelled to register with DVA

unless they want to claim for a service-related injury or illness, the extent

of mental ill-health among ex-serving men and women is unknown. Given the

typical presentation some eight to 10 years after discharge and the experience

following the Vietnam War of delayed onset of symptoms, it is highly likely

that there are significant numbers of veterans with service related mental

ill-health who are as yet unknown to DVA.[42]

2.40

Phoenix Australia noted that 'many mental health problems may not be

obvious while the person is still serving and may not become apparent until

months or years after serving'.[43]

The RSL commented that 'the lack of information in this area is concerning but

the sheer numbers of veterans seeking RSL support alone is enough to indicate

that this is a severe problem'.[44]

Soldier On also expressed concerns with DVA data, noting that 'once a person

discharges from the military there are no records kept of their on-going or

developing physical or mental health concerns, hospitalisation or deaths unless

the treatment is provided through DVA'.[45]

2.41

The record-keeping policies and processes for both Defence and DVA will

be considered in greater detail in Chapter 5 of this report.

Suicide

2.42

Suicide is a leading cause of death in Australia. In 2013, deaths due to

suicide occurred at a rate of 10.9 per 100,000 people. The median age at death

for suicide was 44.5 years for males, 44.4 years for females, and 44.5 years

overall. In comparison, the median age for deaths from all causes in 2013 was

78.4 years for males and 84.6 years for females.[46]

Of deaths due to suicide, 75 per cent are male, making it the tenth leading

cause of death for males in Australia.

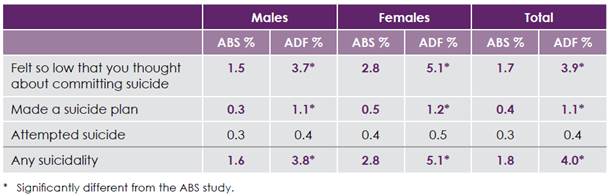

Suicidality in ADF population

2.43

Defence advised the committee that since 2000, 108 ADF members are

suspected or have been confirmed to have died as a result of suicide.[47]

The MHPW study found that the rate of suicidality (thinking of suicide and

making a suicide plan) in the ADF was more than double that in the general

community; however the number of suicide attempts was not significantly greater

than in the general community and the number of reported deaths by suicide in

the ADF were lower than in the general population when matched for age and sex.

The study noted that there is a gradation of severity of suicidality in the

ADF, ranging from those with suicidal ideation (3.9 per cent) through to those

making a plan (1.1 per cent) and those actually attempting suicide (0.4 per

cent) (see Table 2.5).

Table 2.5–Estimated prevalence of

12-month suicidality, by sex, ADF and ABS data

Department of Defence, Mental

Health in the Australian Defence Force: 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and

Wellbeing Study Report, p. xxi.

2.44

The MHPW study commented that although ADF members are more symptomatic

and more likely to express suicidal ideation than people in the general

community, they are only equally likely to attempt suicide and less likely to

complete the act, and that this suggests that 'the comprehensive initiatives on

literacy and suicide prevention currently being implemented in Defence may, in

fact, be having a positive impact'.[48]

Suicidality in ex-service

population

2.45

DVA informed the committee that it has determined 85 claims relating to

death by suicide over the last ten years (to 31 December 2014). Of the 85

claims, 57 were accepted as service related; and of the 57 claims, 22 veterans

were aged 55 years or under at death. DVA advised that it is only made aware of

a death by suicide when a dependant lodges a compensation claim:

Generally, DVA only becomes officially aware of a death by

suicide of a veteran through the dependant's compensation claim process. This

occurs when a claim for compensation is lodged by a dependant in respect of the

death of that veteran and a cause of death must be investigated to establish a

link to service.[49]

2.46

A number of submissions highlighted the difficulty of accurately

estimating suicidality of veterans and expressed concern about the lack of data

regarding veteran suicide.[50]

Some submitters called for the government to monitor and maintain a public

record of suicide, suspicious death, single vehicle accidents and other deaths

by misadventure.[51]

The RSL also noted that suicide data is further complicated by deaths that are

not definitively confirmed to be suicides:

When death occurs as a result of self-harm in association

with existing mental health difficulties, unless it is very clear, e.g.

self-inflicted injury or overdoses, then the cause of death is very often left

open by the coroner. This action produces inaccurately low figures with regard

to suicide figures particularly when substance abuse, motor vehicle accidents

and cliff falls are involved. In addition there may be no mention of a mental

health history on the death certificate at all.[52]

2.47

Soldier On stressed the importance of accurate and transparent data

regarding veteran suicide noting that without accurate data it is impossible

for both government and non-government support providers to properly address

the issue:

...very little is known about how many veterans are taking

their own lives. Community groups are gathering anecdotal data, but without any

reliable sources collecting the information, it is impossible for any support

provider (government or non-government) to truly understand the extent of the

issue...it is our recommendation that data around the ongoing health implications

among serving and ex-serving members over the past five to 10 years is collated

as a priority by the Department of Veterans' Affairs. It is also important this

information is gathered regularly and made available to the public in a

de-identifiable format, in order for the issues to be quantified and a reasoned

response and solution be prioritised.[53]

2.48

DVA advised the committee that in November 2014 it commissioned the

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare to carry out a data matching

exercise between deceased military superannuants from ComSuper and the National

Death Index for reported incidents of suicide from 2001 onwards. DVA advised

that it expects to receive the findings from this work in late 2016.[54]

DVA has also commissioned the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and

Prevention (Griffith University), to conduct a literature review to examine

suicide amongst veterans in Australia and internationally, and how this

compares to the general population.[55]

2.49

Recent research into suicidality in Australian Vietnam veterans and

their partners found that suicidality was higher in veterans than in the

Australian community. The study assessed the lifetime suicidality of a cohort

of 448 Australian Vietnam veterans during in-person structured psychiatric

interviews that permitted direct comparison with age-sex matched Australian

population statistics finding that:

Relative risks for suicidal ideation, planning and attempts

were 7.9, 9.7 and 13.8 times higher for veterans compared with the Australian

population ...PTSD, depression, alcohol disorders, phobia and agoraphobia were

prominent predictors of ideation, attempts and suicidal severity among

veterans.[56]

2.50

Similarly, the 2005 Australian National Service Vietnam Veterans:

Mortality and Cancer Incidence report found that there was a significant

increase in the relative rate for suicide for veterans:

There was a significant increase in the relative rate for

suicide, based on 129 deaths observed amongst the National Service veterans and

115 deaths observed amongst non-veterans. This gave a relative rate of

1.43...this relative rate was higher than that noted in the previous study of

this cohort.[57]

2.51

Dr Kieran Tranter pointed to the Veterans Line statistics as a possible means

of providing insight into veteran suicidality, noting with concern the

increasing number of clients identified as at significant risk of suicide or

self-harm:

The Veterans Line also provides a call-back service for

clients who may present as being at significant risk of suicide or self-harm.

In 2012-13 the service identified and made 52 call-backs to veterans who

presented such risks compared to only 21 call-backs in 2011-12. The number of

call-backs made in 2013-14 rose significantly again to 122 clients being

identified as requiring the call back service...these figures are alarming, as

the numbers of clients who have been identified as at significant risk of

suicide or self-harm have doubled each year since 2011-2012.[58]

Prevalence of mental ill-health in families of ADF members and veterans

2.52

A number of submissions highlighted the impact ADF members and veterans

struggling with mental ill-health can have on their families.[59]

The War Widows' Guild of Australia told the committee that 'veterans with

PTSD/mental ill-health issues have impacts on the entire family', explaining

that the mental health of the families of ADF members and veterans are impacted

as a result of the ADF member or veterans' service:

There is anecdotal evidence that many War Widows have

suffered forms of abuse, be it physical, emotional or psychological as a result

of their spouse/partner/significant others service in an area of conflict.

These women have been reluctant to discuss their issues for fear of social

rejection, isolation, embarrassment, feeling that this violence is 'their

fault' rather than as a symptom of their spouses/partners mental ill-health.[60]

2.53

The committee received evidence from ADF members' and veterans'

partners, describing their experiences living with and supporting partners

struggling with mental ill health.[61]

Miss Alanna Power detailed her experiences supporting her partner Mr Ryan

Geddes, during an incident in which he was engaging in dangerous self-harm:

Ryan [her partner] was deployed to Afghanistan as a combat

engineer in 2010 on MTF1 and again in 2011 in a non-combat role...As a combat

engineer, Ryan experienced many traumatic events, some of which I know he will

probably never tell me about. In 2014 he was diagnosed with PTSD, anxiety and

depression, although his first symptoms appeared in early 2012...Some of the

symptoms that Ryan experiences include major anxiety about being in public or

meeting new people, hypervigilance, night terrors, self harming, serious

depressive episodes, anger control issues, lack of empathy and the inability to

sleep without medication.

In October 2014 I came home from work to find Ryan with a

large hunting knife engaging in a serious self harming incident. I was on my

own and could not get the knife off him and so the police and paramedics were

called to diffuse the situation. The knife was only handed over once the police

pepper sprayed Ryan in the face...I was informed by the hospital that Ryan was in

a dissociative state when he was self harming. This episode was triggered by

the air conditioning blowing up in Ryan's car while he was driving. Essentially

he was transported back to a traumatic event which occurred in Afghanistan.[62]

2.54

Mr Geddes told the committee of his struggle identifying his mental

illness due to the pressure and stigma associated with mental ill-health as

well as the impact that this had on Miss Powers:

I knew that there was something wrong. I did not know what it

was. I was angry. I was drinking a lot, and I was taking a lot of it out on

Alanna. Yes, I did know that there was something there, but I did not want to

admit to it...It was a weakness, and up until early this year I still thought of

it as a weakness. Until all my friends told me, my partner told me, my parents

told me, and I just told them to get you know, that I was fine. I did not want

to process; I did not want to go through that way because I wanted to still be

able to work. I thought if I do say anything about this, then that is me, I am

never going to be able to get a job doing what I want to do again.[63]

2.55

Mrs Catherine Lawler told the committee about her experience supporting

her husband, Mr John Lawler, describing herself as 'worn out and worn down' and

'angry too'. Mrs Lawler explained that she disengaged emotionally from her

husband to cope with the situation and even contemplated suicide to 'stop

[herself] from sharing his pain':

John has withdrawn from involvement in the day to day tasks

of our domestic lives, and I undertake all household chores, inside and outside

the house, and financial dealings. I generally liaise with doctors, government

departments, his RSL advocate, etc. on John's behalf. We will often go for long

periods where I also do all of the driving. All of this has had an impact on my

physical health, and I am constantly fatigued. I have gradually withdrawn from

the workforce to be John's fulltime carer.

The anger and rage that engulfed John increased the tension

between us to unbearable levels. I tried to be supportive, I tried to

understand, but I was struggling. I was worn out and worn down. There were many

times when I was angry too. I know I could not be his wife and his psychiatrist

too.

I found myself in a position where the best thing to do was

disengage from John, go about my daily business and pretend I did not care. But

I did care, and his pain was my pain. I eventually found myself thinking that

if I killed myself I could stop myself from sharing his pain. But I couldn't

kill myself because I knew my family would never forgive him. Then I realised

that if I was to drive my car into a tree no-one would know it was deliberate...[64]

2.56

The Vietnam Veterans' Federation of Australia asserted that the children

of Vietnam veterans 'have had a 300 per cent higher suicide rate than their

equivalents in the general community, a statistic resulting from veterans'

families becoming dysfunctional because of veteran fathers' war caused

psychological illnesses'.[65]

2.57

Recent research into suicidality in Australian Vietnam veterans and

their partners found that relative risks for suicidal ideation, planning, and

attempts were 6.2, 3.5 and 6.0 times higher for partners of Australian Vietnam veterans

compared with the Australian population.[66]

Significance and impact of mental ill-health

2.58

The committee received considerable evidence from individuals sharing

their experiences with mental ill-health and the enormous impact that it has

had on their career, families, and overall quality of life.[67]

Phoenix Australia outlined the enormity of the impact on the individual's

quality of life and on society more broadly:

A large body of data attests to the substantial functional

impairment and reduced quality of life associated with mental health diagnosis.

That is, these disorders substantially impair the person's ability to function

in social relationships, including with partners, children, friends, and other

loved ones. Rates of separation and divorce are high. Mental health disorders impair

the person's ability to function in their normal role (e.g., in employment,

study, or parenting).

...veterans with mental health problems showed higher rates of

unemployment, social dysfunction, martial separation, reduced engagement with

productive activity and poorer quality of life...The number of disability and

incapacity claims associated with mental health problems that are accepted by

DVA is further testament to the impairment associated with these conditions.

The human cost in terms of distress, poor quality of life,

family breakdown, and suicide, as well as the financial costs in terms of lost

productivity, health care, and benefits, are enormous.[68]

2.59

The significance of mental health on ADF members and veterans was also

highlighted by KCI Lawyers, which specialise in assisting veterans seeking

compensation, which noted that:

The significance of psychological conditions is substantial

given the effects on the Veterans' capacity to not only remain in the ADF, but

to function at a reasonable level within the Defence community and to coexist

harmoniously with their family, with their peers and friends. Their ability to

find and maintain civilian employment is also a major issue for those suffering

from PTSD.

Unlike a 'physical' injury that, at least can be explained

and the impact self-evident, PTSD is devastating to the individual with respect

to their self-esteem, motivation and outlook on life. A Veteran cannot simply

'explain' why they are unable to work, or spend large amounts of time in

relative isolation and medicated to treat and intangible condition. Their sense

of self-worth is degraded, their relationship with their spouses or partners

suffers, often irreparably, their confidence to deal with their families,

friends, peers and strangers gradually erodes.[69]

2.60

One submitter told the committee of their experience with PTSD and Depression

and its impact on their life following medical discharge for mental ill-health.

The individual told the committee of the profound impact that mental ill-health

has had on their relationships with family and friends and explained its impact

on their ability to live and function in society, highlighting the compounding

nature of the impacts of mental ill-health and their feelings of hopelessness

and despair:

You see when you suffer from mental illness you become like a

deer in headlights. Anxiety and stress sinks in and seemingly simple tasks

become complex and distressing.

At this time my relationship with my parents began to break

down. My behaviour was erratic and I also become involved in alcohol related

incidents in town. This is not good in a small country town and before things

got out of hand, I moved to my grandmother's house on the South Coast...unfortunately

my behaviour in civvy street had not improved...my time at my Grandmother’s had

deteriorated along the same lines as they had with my parents.

Poor behaviour and confrontations with friends and family

made my time there untenable. This was particularly distressing for me; as for

my entire life I’d had an extremely close relationship with my grandmother.

There was only one option and that was for me to leave. I had nowhere else to

go. I was burning bridges wherever I went leaving a trail of anger and

resentment. I had to be away from everyone for their sake and my own.

I was in a very dark place. I had very little money, I’d

ostracized myself from all my family and friends, I had no one to turn to. I’d

hit rock bottom. I literally went bush and went through the worst period of my

life. I hated everyone and I hated myself and I was just on my own having

nightmarish conversations with myself. I was broke, any claim outcome was at

least 3 more months away but it didn’t matter. I wasn’t going to make it.[70]

Committee view

2.61

The committee expresses its deep respect for those Australians who serve

and protect our country, putting their life, as well as their physical and mental

health, on the line. The committee commends Defence and DVA's ongoing

commitment to improve the understanding of the prevalence of mental ill-health

and the impact that ADF service can have on the mental health of its members

and veterans. The committee acknowledges the unique stressors of ADF service.

During their service, ADF members must manage various day-to-day stressors

including significant periods of time away from home, family, and friends in

addition to the increased risk of exposure to potentially traumatic experiences.

2.62

The committee notes the difficulty of clearly differentiating between

traumas experienced during ADF service and traumas experienced in ADF members'

private lives, and that for clear conclusions to be drawn regarding the impact

of ADF service 'traumas experienced during military service and in the private

lives of ADF members need to be separated'.[71]

To this end, the committee supports the Transition and Wellbeing Research

Programme and looks forward to the publication of its findings.

2.63

The committee also appreciates that mental ill-health in veterans will

often go unrecognised and undiagnosed many years after leaving the ADF. This

creates real challenges for policy makers and mental health practitioners who

are focusing on strategies for the early detection and treatment of mental

ill-health.

2.64

The committee understands that DVA is limited in its ability to measure

the prevalence of mental ill-health in veterans to those veterans who have

sought assistance or made a claim with DVA. The committee notes that the number

of veterans who have made claims may represent only a small proportion of those

veterans who have or are struggling with mental ill-health. The Transition and

Wellbeing Research Programme will provide invaluable data regarding the

prevalence of mental health in veterans as well as highlighting which areas

still need to be investigated.

Suicide

2.65

Since 2000, more than 100 ADF members are suspected or have been confirmed

to have died as a result of suicide. It is a terrible tragedy whenever any ADF

member loses their life during their service; however, when a member dies as a

result of suicide it is particularly devastating for the family, friends, and

colleagues of the deceased member.

2.66

A number of submissions called for the introduction of a government maintained

public record of ADF members and veterans who have died as a result of suicide.

The committee agrees that accurate data regarding the rate of suicide among ADF

members and veterans is an important element of addressing suicidality and

formulating policy to address it. The committee has carefully weighed the

arguments in favour of a public record of ADF members and veterans who have

died as a result of suicide against the risk to ADF members', veterans', and

their families' right to privacy. On balance, the committee is not in favour of

recommending the creation of a public record of ADF members and veterans who

have died as a result of suicide.

2.67

The committee is satisfied that current pathways for scrutinising the

deaths of ADF members, and (through civilian pathways) veterans, are adequate. Defence

currently records the death of members during their service, including those

suspected or confirmed to have died as a result of suicide. It is much more

difficult, however, to determine the number of veterans who have died as a

result of suicide. The committee notes that DVA has commissioned studies from

the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and the Australian Institute for

Suicide Research and Prevention to investigate the prevalence of suicide among

veterans. The committee looks forward to the publication of its findings.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page