The role of law enforcement and serious and organised crime

4.1

This chapter discusses current law enforcement measures to combat the

supply, distribution and consumption of crystal methamphetamine (and other

illicit drugs) in Australia. It first provides an overview of a number of

current Commonwealth law enforcement activities and key collaboration aimed at

targeting criminal groups' illicit activities. This is followed by

consideration of data on detections of methamphetamine at Australia's border,

existing border control measures and known embarkation points of crystal

methamphetamine being trafficked to Australia. Finally, this chapter considers

the role of outlaw motorcycle gangs (OMCGs) and other organised criminal groups

in the manufacture, importation and sale of crystal methamphetamine in

Australia.

4.2

The next chapter, chapter 5, considers Australia's law enforcement

approach to tackling crystal methamphetamine in the context of the National Ice

Taskforce (NIT) and the National Ice Action Strategy (NIAS).

Commonwealth's law enforcement activities

4.3

The principal agencies responsible for the Commonwealth's law

enforcement measures to combat illicit drugs are:

-

the Australian Border Force (ABF):

-

the Australian Crime and Intelligence Commission (ACIC);

-

the Australian Federal Police (AFP);

-

Attorney-General's Department (AGD);

-

the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC);

-

the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC);

and

-

the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP).

4.4

The Commonwealth is primarily responsible for controlling illicit

substances at Australia's borders. The state and territory governments have

responsibility for criminal laws and regulatory controls, such as laws for

possession, trafficking or manufacturing of illicit drugs. Regulation of the sale

of precursor chemicals, including recordkeeping and reporting, is also the

responsibility of the states and territories.[1]

4.5

Collaboration between Commonwealth agencies and the state and territory

law enforcement bodies is common, and has significantly improved over time.

Victoria Police highlighted the importance of collaboration:

From a law enforcement perspective, a collaborative response

or approach between the Commonwealth law enforcement agencies and the state and

territory police is absolutely critical. My experience working in Victoria

Police on organised crime is that, in terms of a collaborative approach, the

better and more involved we get in working together, the better chance we have

of targeting this issue from a law enforcement perspective.[2]

4.6

Collaboration between agencies is demonstrated by a number of national

initiatives and committees that provide a holistic and inter-agency approach to

dealing with illicit drugs, such as:

-

the Serious Organised Crime Coordination Committee (SOCCC);

-

the Australian Gangs Intelligence Coordination Centre (AGICC) and

the National Anti‑Gangs Squad (NAGS);

-

the National Criminal Target List (NCTL); and

-

Taskforces Eligo and Vestigo.

Serious Organised Crime

Coordination Committee

4.7

The SOCCC is a national committee that prioritises, endorses and

coordinates operational strategies to deal with serious and organised crime

investigations. Representatives of all Australian police jurisdictions (as well

as New Zealand) participate in the SOCCC, together with the ACIC, DIBP, AUSTRAC

and the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).[3]

The SOCCC considers and endorses key law enforcement strategies, such as the

National Organised Crime Response Plan 2015–18 (Crime Response Plan),[4]

which outlines law enforcement activities.[5]

4.8

The SOCCC also supports the work of State and Territory Joint Management

Groups (JMGs). The management and prioritisation of serious and organised crime

activities are managed through JMGs, as well as the implementation of

multi-agency strategies. JMGs are also supported by Joint Analysist Groups that

'identify, coordinate and prioritise intelligence about targets and threats,

and provide JMGs with information to support local decision making and

de-confliction of cross jurisdictional targeting'.[6]

4.9

Western Australia Police (WA Police) acknowledged the vital role that

collaborative efforts, such as the SOCCC, play:

What I will say about our cooperation with our Commonwealth

partners—having been involved in drug investigations as a detective and now

running state crime in the operational area—is that our partnerships have never

been better. We are no longer acting with a silo mentality. With the creation

of the [Joint Organised Crime Task Force] and working out the Serious and

Organised Crime Coordination Committee, down to our joint management groups and

to our strategy groups, and then the local efforts here in Western Australia

and across Australia, the information sharing and the cooperation have never

been better.[7]

4.10

One activity outlined under the Crime Response Plan is the National

Law Enforcement Methylamphetamine Strategy, established to respond to

organised crime groups' activities. This strategy outlines agencies' roles and

aligns 'responsibilities for...enforcement, intelligence collection, public

engagement and awareness'.[8]

The overall goal of the strategy is to improve cross-border coordination and

reduce the supply of methamphetamine.[9]

Australian Gangs Intelligence

Coordination Centre and the National Anti-Gangs Squad

4.11

The AGICC is housed within the ACIC, and coordinates an intelligence led

response to OMCGs and other gangs operating across jurisdictions. The AGICC includes

representatives from the AFP, ATO, ABF, DIBP and the Department of Human

Services. Intelligence gained through the AGICC informs the activities of the

AFP's NAGS and 'aims to:

-

develop and maintain the national and transnational picture of

criminal gangs impacting on Australia;

-

strengthen the coordination and sharing of gang intelligence by

complementing existing Commonwealth and [s]tate and [t]erritory efforts;

-

provide high quality tactical, operational and strategic

intelligence advice to the NAGS and its members;

-

drive the proactive discovery and development of new criminal

gang intelligence insight; [and]

-

identify new targeting opportunities to complement existing

Commonwealth and State and Territory investigative efforts'.[10]

National Criminal Target List

4.12

The NCTL is a national listing of known organised crime groups operating

in Australia based on input from Commonwealth, state and territory agencies.

The Commonwealth government informed the committee that more than 60 per cent

of the high risk criminal targets on this list are known to be involved in the

methamphetamine market.[11]

Eligo 2 National Taskforce

4.13

In December 2012, the Eligo National Taskforce was authorised to

coordinate activities to tackle high risks in the alternative remittance sector

and operators of the informal value transfer systems.

4.14

After the Eligo National Taskforce ended, Eligo 2 was established to

target high priority international and domestic money laundering operations.

This taskforce comprised members from the ACIC, AFP, AUSTRAC and other state,

territory and international partners. The ACIC reported that Eligo 2 resulted

in:

...the disruption of very significant global money laundering

operations and drug networks, resulting in the seizure of over $80 million in

cash, the restraint of more than $59 million worth of assets and in excess of

$1.6 billion in street value of drugs which have been taken from the streets.

The work of the task force does include long-term prevention strategies. There

are significant arrests that have been made by our international partners.

Those have severely disrupted a number of networks.[12]

4.15

Eligo 2 ceased operation on 31 December 2016.[13]

Vestigo Taskforce

4.16

The Vestigo Taskforce began in November 2016 to target transnational

serious organised crime activities that impact on Australia and international

partners. It coordinates efforts by Commonwealth, state and territory partners,

as well as international partners including those from the Five Eyes Law

Enforcement Group.[14] [15]According

to the ACIC, the Vestigo Taskforce:

...provides a framework for the ACIC to enhance our

international engagement and collaboration in response to the threat posed by

high risk serious and organised crime entities based overseas or with direct

links to criminal entities based overseas impacting adversely on Australia.[16]

4.17

Building upon the work of Eligo 2 and Taskforce Morpheus, Vestigo has

identified and is addressing a range of criminal issues, including the

importation of methamphetamine into Australia, cyber-crime, money laundering

and serious financial crime.[17]

...identified and are addressing a range of serious and

organised crime activities which continue to pose a significant threat to the

Australian community and its national interests, including but not limited to

the importation methylamphetamine into the Australian market, evolving threats

posed by serious organised crime groups within the national security

environment, the criminal exploitation of cyber technologies, money laundering

and serious financial crime.

Detections of illicit substances at Australia's border

4.18

In its Illicit Drug Data Report 2015–16 the ACIC reported on

illicit drug detections at Australia's border. Since 2008–09, there has been an

increase in the number of detection of amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) at

Australia's border, with a drastic increase since 2011–12. However, the number

of border detections for 2015–16 decreased by 13.3 per cent,[18]

a significant change from 2014–15, when there was a 47 per cent increase.[19]

4.19

There were 3017 border detections of ATS in 2015–16, weighing a total of

2620.6 kilograms. In 2014–15, there were 3478 detections, weighing

3422.8 kilograms, the highest number on record. By weight, methamphetamine

was the predominant drug detected at the border: 64.2 per cent of all ATS

detections were crystal methamphetamine.[20]

4.20

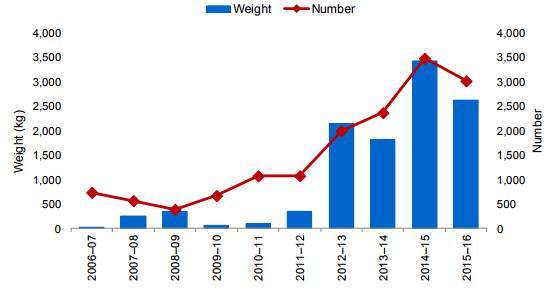

Figure 9 shows the number and weight of ATS detections (excluding MDMA)[21]

at Australia's border from 2006–07 to 2015–16.[22]

Figure 9: number and weigh of ATS

detections between 2006–07 and 2015–16

4.21

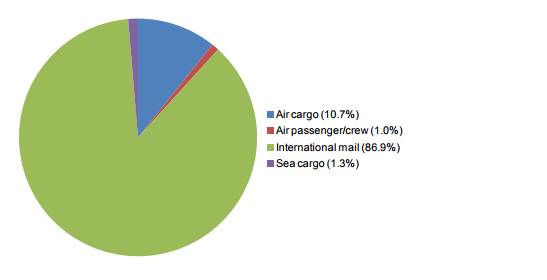

ATS are imported into Australia via four pathways: air cargo; air

passengers and crew; international mail; and sea cargo. Of the four pathways, the

majority of detections were made in international mail (86.9 per cent),

followed by air cargo (10.7 per cent), sea cargo (1.3 per cent) and air

passenger and crew (1.0 per cent).[23]

4.22

By weight, international mail detections are often smaller amounts of

ATS. A technique known as 'scatter imports' is used by criminals, which involves

sending large volumes of postal items each containing a small amount of drugs

to multiple addresses or post box numbers.[24]

4.23

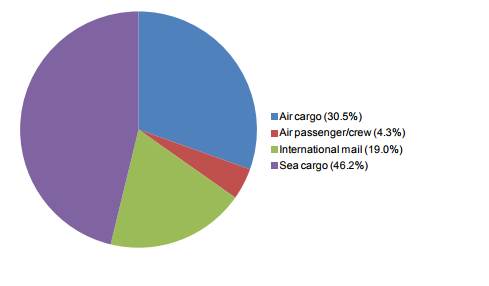

While international mail represents the bulk of detections by number, most

ATS by weight is trafficked to Australia in sea cargo. In 2015–16, sea cargo

accounted for 46.2 per cent of total weight, followed by air cargo (30.5 per

cent), international mail (19.0 per cent) and air passenger/crew (4.3 per

cent).[25]

4.24

Figure 10 shows the number of ATS detections (excluding MDMA) at

Australia's border, as a proportion of the total detections and by the method

of importation in 2015–16.[26]

Figure 10: ATS detections by number

in 2015–16

4.25

Figure 11 shows the number of ATS detection by weight (excluding MDMA)

at Australia's borders as a proportion of total weight and method of

importation in 2015–16.[27]

Figure 11: ATS detections by weight

in 2015–16

Major seizures in 2016–17

4.26

The AFP and ABF regularly release details of methamphetamine seizures. Major

seizures since August 2016 have included:

-

17 June 2017: 200 kilograms of crystal methamphetamine were

detected in the air cargo of a flight from Taiwan to Sydney.

-

4 January 2017: 195 kilograms of methamphetamine were detected

via sea cargo from Hong Kong to Sydney.[28]

-

Two Malaysian nationals were arrested and charged with possessing

over 100 kilograms of methamphetamine on 23 December 2016. This seizure

was worth an estimated street value of $128 million.[29]

-

21 December 2016: four men were charged with attempted possession

of approximately 10 kilograms of methamphetamine disguised as 'aircraft cylinders'.[30]

-

18 August 2016: a man was arrested and charged with importing

210 kilograms of methamphetamine hidden in 12 boxes of women's clothing.

The estimated street value was $210 million.[31]

-

4 August 2016: two people were arrested after anomalies were

found in timber logs imported from Africa via sea cargo. 154 kilograms of

methamphetamine were found, with an estimated street value of $115 million.[32]

Border control measures

4.27

Australia's border control measures continue to be improved, through

additional screening of incoming sea and air cargo, and through the

establishment of the National Forensic Rapid Lab and Forensic Drug Intelligence

Capability (Rapid Lab).

4.28

As discussed in paragraphs 4.23–4.24, sea cargo and air cargo detections

accounted for 76.7 per cent of all illicit drug detections in 2015–16. The NIT's

final report stated that the sharp increase in detections over recent years was

due to a rise in both high and low volume smuggling into Australia. Another

contributing factor to the increase in detections, especially during the

2014–15 reporting period, was additional screening of incoming cargo occurring

from July 2014.[33]

4.29

In addition to screening of air and sea cargo, law enforcement agencies

have sought to enhance the detection of illicit drugs through the international

mail system. This enhancement has been achieved through the creation of the

Rapid Lab.

4.30

The committee was informed that any illicit drugs detected in the

international mail system is:

...put through the rapid lab process where it then goes through

a series of filters. So it will go through an intelligence filter, a DNA filter

and a fingerprint filter trying to do an analysis of those items to determine

who is actually bringing the import in. So, instead of chasing after every

single mail item trying to work out who is doing it, which is next to

impossible from a resource point of view, we are now taking a really

sophisticated approach. It is an intelligence-driven process. All mail items

with narcotics are taken to one place and put through this process. Then we can

determine who the organisers are, and they are who we are going after.[34]

4.31

AUSTRAC advised the committee that it uses the information obtained through

the Rapid Lab to develop financial profiles of those sending illicit drugs,

which are shared with DIBP and then linked with parcel post importations.[35]

4.32

The Rapid Lab resides within Sydney's Clyde mail exchange, and it is at

this location that seizures are made. The AFP anticipates that by the end of

2017, all international mail will be received and processed through the Clyde

mail exchange. Once processed, ABF will utilise its own international networks

to find out more about the source of the illicit material, information which

will also go into a single database. This database will then be used to target

future incoming mail.[36]

Embarkation points

4.33

In 2015–16, the DIBP identified 49 countries as embarkation points for

ATS. In order of the total number of detections, these were:

-

the Netherlands (457 detections);

-

China and Hong Kong (408 detections);

-

the United Kingdom (UK) (398 detections);

-

Singapore (272 detections);

-

Germany (201 detections);

-

India (188 detections);

-

Thailand (169 detections);

-

Malaysia (143 detections);

-

Canada (142 detections); and

-

the United States of America (136 detections).[37]

4.34

The three main embarkation points, by weight, were:

-

China and Hong Kong (1458.7 kilograms);

-

Taiwan (289.2 kilograms); and

-

Nigeria (222 kilograms).[38]

Role of outlaw motorcycle gangs and other organised criminal groups

4.35

Law enforcement agencies frequently refer to the role of OMCGs and other

organised criminal groups as facilitators of the illicit drug market in

Australia. The role of OMCGs and other organised criminal groups is explored in

the following sections.

Outlaw motorcycle gangs

4.36

OMCGs are known to supply of methamphetamine in Australia. The

Commonwealth government reports that approximately 45 per cent of high

risk criminal targets in the methamphetamine market are OMCGs.[39]

These gangs have strong links with both domestic and international criminal

groups, have access to precursor chemicals and have established drug

distribution networks. OMCGs use violence, have access to weaponry and are specialised

in money laundering.[40]

Often, OMCGs' illicit activities are merged with legitimate business interests,

such as the 'transport industry, tattoo parlours, gyms and nightclubs that

allow for the distribution of methamphetamine to a wider drug market'.[41]

4.37

According to NSW Police, OMCGs are heavily involved in the drug market,

but:

The percentage of their productivity out in the field is

almost impossible to guess because we do not have visibility on the entire

market. But certainly there is more than enough anecdotal evidence to satisfy

me and the drug squad that pretty much all the outlaw motorcycle groups are

heavily involved in methamphetamines.[42]

4.38

The National Drug Law Enforcement Research Fund's report titled Sydney

methamphetamine market: Patterns of supply, use, personal harms and social

consequences notes that OMCGs 'play a dominant role in the clandestine

production of methamphetamine in Australia'[43]

but, within the Sydney market, they are influential in the domestic production

and distribution of base methamphetamine, rather than crystal.[44]

These groups are also heavily involved in the distribution of precursors,

reagents and the glassware required to smoke crystal methamphetamine.[45]

4.39

Other state and territory law enforcement agencies also spoke of OMCGs'

involvement in the methamphetamine market. The Northern Territory (NT) police

reported that OMCGs (and other organised crime groups) have had a significant

influence on the supply of amphetamines to the territory. The NT police has

seen a correlation between the increase in the supply of amphetamines in the

territory and the increase in the number of members of NT-based OMCGs.[46]

4.40

In Tasmania, the police force's focus is on aggressively targeting motor

cycle gangs and preventing the establishment of clubrooms in the state:

We impact on them as much as we possibly can, whether that is

through major operations or using Treasury to close down their clubhouses and

take their licences off them. Certainly one motorcycle gang from the mainland

have tried to set up a group here, and we have targeted those quite

aggressively with a view to making it uncomfortable. We are letting them know

that we do not want them to set up in Tasmania. They are not welcome. They are

part of an organised crime group. They are not welcome in Tasmania.[47]

4.41

WA Police told the committee that its force has no doubt that OMCGs are

involved in a range of criminal activities, 'including where a payment has

possibly been made for a consignment and people are threatened or extorted'.[48]

4.42

The Victoria Police informed the committee that motorcycle gangs are a

particular concern, especially in rural communities. In some instances, there

have been turf wars between motorcycle gangs and:

...outlaw motorcycle gangs have probably got really good

distribution networks throughout the country; they have particularly expanded

in Victoria. They have set up a lot of clubs in rural communities, and we have

seen violence play out in those communities between different clubs. One

example would be Mildura, where we had the Rebels outlaw motorcycle gang

initially set up its operations there and then the Comancheros took over and it

was a very violent takeover within that particular community. They terrified

the individuals there until we actually managed to arrest the main players for

the violence and the drug trafficking that was going on.[49]

4.43

Submitters and witnesses informed the committee that there are a number

of challenges in combating OMCGs. Mr Mick Palmer said one challenge facing

police is that the higher up the drug supply chain an investigations gets:

...the more sophisticated the people and the more likely that

they will call a lawyer within two minutes. They will not answer any questions

unless you find them with the drugs in their possession. They will deny involvement

in whatever it is you are alleging they are involved in.

It becomes difficult. And it must be considered that the

reality in this country, particularly with ice but also with regard to most

illicit drugs, is that the marketplace is essentially owned by the outlaw

motorcycle gangs. They talk to nobody, they answer no questions and they are

very difficult to infiltrate. Police officers who go undercover take a very big

risk and can quite easily be killed, as has happened in the United States. It

is a very difficult proposition, which is only very rarely considered.[50]

4.44

Another issue, raised by Victoria Police, is the lack of nationally

consistent OMCG legislation which 'results in displacement to states such as

Victoria which is perceived by opportunists as an arena where OMCGs, gangs

and/or organised crime groups can move their drug operations'.[51]

4.45

The view that OMCGs are key players in the illicit drug market was

questioned by Dr Terry Goldsworthy from the Criminology Department at

Bond University. Dr Goldsworthy questioned the role of OMCGs in the

Queensland illicit drug market, arguing that they are not central to the

illicit trade, contrary to previous thinking. In his analysis of data on OMCG

member arrests in Queensland, Dr Goldsworthy found that over a six year

period the supply of illicit drugs only accounted for 0.2 per cent of arrests;

the production of illicit drugs accounted for 0.3 per cent; and drug

trafficking accounted for 0.9 per cent. Dr Goldsworthy's analysis concluded that

although OMCGs are players in the illicit drug market, they are not major

players.[52]

Dr Goldsworthy felt that this misconception is due to OMCGs being an easy

target:

They are very visible—they were very visible up here but they

are not anymore—and we do get a lot of media exposure on arrests involving

bikies, because they are great media ammunition...I just do not think that we are

seeing the number of arrests to justify saying they are the major players.

Where do they fit into the organised crime chain? If you look at drug activity

and the functional level of that, are they manufacturers and wholesalers? Again

I have not seen the evidence for that. We have had claims from the police that

they were heavily involved in clandestine amphetamine labs, but we never saw

any data to back that claim up, and I would have thought it would be quite easy

to say, 'We located 380 labs. Of those labs, this many resulted in the arrest

of an OMCG member attached to it. We have never seen that come out to back up

the claim that they were heavily behind the labs. Certainly they do play a role

in distribution and retailing. I think you can see that coming out in some of

the arrests. We know that in Queensland the criminality within the gangs

averages about 40 per cent; so 60 per cent do not have criminal histories and

40 per cent do.[53]

4.46

The NIT's final report discussed the issue of OMCG involvement in

crystal methamphetamine distribution and made recommendations to tackle the

issue. It found that OMCGs play a significant role in the distribution of

crystal methamphetamine and other illicit drugs in rural and remote

communities, providing a 'competitive advantage over other organised crime

groups in this context because of their geographic diversity'.[54]

Subsequently, the NIT recommended the Commonwealth government work with the

states and territories through the AFP's NAGS to:

...tackle the significant outlaw motorcycle gangs' involvement

in ice production, importation and distribution, and through the [AFP's] Rapid

lab capacity to disrupt regional ice distribution through the mail and parcel

post.[55]

4.47

The NIAS makes minimal reference to OMCGs, however, it did note that law

enforcement agencies would '[w]ork through existing structures to disrupt the

production and supply of ice in regional and remote areas' as part of the NIAS.[56]

Organised criminal groups and the

international supply chain

4.48

Pursuant to the Australian Crime Commission Act 2002, serious

and organised crime is an offence:

- that involves 2 or more offenders and substantial

planning and organisation; and

- that involves, or is of a kind that ordinarily

involves, the use of sophisticated methods and techniques; and

- that is committed, or is of a kind that is

ordinarily committed, in conjunction with other offences of a like kind.[57]

4.49

Serious offences include crimes such as theft, fraud, tax evasion, money

laundering, illegal drug dealings, illegal gambling and cybercrime.[58]

4.50

Internationally, organised crime groups are defined, under Article 2 of

the United Nation's Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, as:

...a structured group of three or more persons, existing for a

period of time, acting on concert with the aim of committing serious crime

offences in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or material

benefit.[59]

4.51

Links between organised criminal groups[60]

and drug trafficking are well documented, and drug trafficking is considered

the leading source of funds and activity for serious and organised crime.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), drug

trafficking is responsible for 20 to 85 per cent of proceeds from organised

crime, followed by counterfeiting and human trafficking.[61]

4.52

According to the ACIC, organised criminal groups are responsible for

much of Australia's serious crime. Primarily driven by money, their activities

include:

-

transnational connections;

-

activities across multiple criminal markets;

-

financial crime (such as money laundering);

-

intermingling of legitimate and criminal enterprises;

-

use of a range of new technologies to facilitate crime;

-

use of specialist advice and professional facilitators; and

-

ability to withstand law enforcement initiatives.[62]

4.53

The ACIC estimates that approximately 70 per cent of Australia's serious

and organised crime threats are based in offshore locations, or have links to offshore

criminal groups.[63]

Mr Chris Dawson, Chief Executive Officer of the ACIC, advised the committee

that the 70 per cent are diverse and international, for example:

Chinese triad or Australians that have located themselves in

other countries, they are organising a lot of the harm in the form of drug

trafficking, money laundering, weapons and all of those sorts of criminal

threats. They are either domiciled offshore or they have very strong

connections with Australian criminals. But our estimation is that 70 per cent

of these have that international or transnational connection. Hence, they are

not just domestically focused.[64]

4.54

Serious and organised criminal groups use professional facilitators,

such as public servants, accountants, lawyers and members of the police, to

assist with their criminal activities. These professionals may be willing

participants or paid helpers, or are coerced through blackmail and

intimidation. Often these professionals have access to specialist knowledge of

and expertise in legal or regulatory systems. This information assists criminal

groups with finding opportunities or to retain and legitimise their proceeds of

crime.[65]

4.55

Within Australia, organised criminal groups are known producers and

distributers of illicit drugs, including crystal methamphetamine. According to

the Commonwealth government, organised criminal groups are drawn to

methamphetamine because of its high profitability and ease of manufacture:

60 per cent of high risk criminal targets on the NCTL are known by

the Commonwealth government to be involved in the methamphetamine market. These

criminal groups were once predominantly focused on heroin or cocaine markets,

but are now focusing predominantly or in part on methamphetamine.[66]

4.56

Organised criminal groups supply Australia's methamphetamine market

primarily from China and Hong Kong. Approximately 70 per cent of all

methamphetamine detected (by weight) in Australia originates from China.[67]

The AFP described the situation in China and South East Asia, as well as

Australia's proximity to these countries:

China, like a lot of countries in Asia, has a serious

domestic drug problem. We are not immune from that sitting here in Australia. I

think if you look at most South-East Asian countries, they do have a serious

ice problem which is growing. We have a situation in our country where we are

paying a lot for drugs. So we are creating the problem. Organised crime is just

obtaining the drug and bringing it to Australia. At the moment, we have an

unprecedented amount of drugs coming onto our shores.[68]

4.57

Mexican and West African organised crime groups are also major suppliers

of methamphetamine to Australia. Other countries known to be linked to the

global supply chain for methamphetamine include Iran, Canada, Indonesia,

Nigeria, Kenya, Thailand, Singapore, Brazil, Congo, South Africa and India.[69]

4.58

The UNODC also identified the growing threat from the methamphetamine

market in Pacific Island Countries (PICs). Criminal groups are using PICs to

trans‑ship precursors and finished methamphetamine products. Fiji, French

Polynesia, Guam, Samoa and Tonga have all reported methamphetamine seizures

over recent years. The UNODC noted that these countries lack the resources to

manage the problem.[70]

Counter to the UNODC's view, the AFP said that it has not seen an increase in

the number of methamphetamine detections coming from the Pacific, although it

has seen an increase in the number of cocaine detections.[71]

The AFP has in place a liaison network through the Pacific to monitor the

illicit drug market and identify vulnerabilities.[72]

4.59

The UNODC considers East Asia, South East Asia and Oceania (Australia

and New Zealand) to be the world's largest market for ATS (with methamphetamine

comprising of the majority of ATS), as well as having the largest number of users

in the world (almost 9.5 million). ATS seizures in the region have

substantially increased, from 12 tonnes in 2008 to approximately 48 tonnes

in 2013; methamphetamine seizures have increased from 11 tonnes in 2008 to 42

tonnes in 2013, accounting for more than 85 per cent of all ATS seizures.[73][74]

4.60

The magnitude of the problem in the region, and the accessibility of the

Australian methamphetamine market, means law enforcement agencies have seen an

increasing amount of crystal methamphetamine coming across Australia's border.

South Australia Police made it clear to the committee that the organised

criminal groups responsible for the importation of illicit drugs:

...are savvy business people. They do not make these things in

the hope that they will find a market; they tap into the market, they exploit

the market. They are very in tune with the market forces and where that market

is. [75]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page