29

May 2020

PDF version [346KB]

Cathy

Madden, Deirdre McKeown, Politics and Public

Administration Section

Penny Vandenbroek, Statistics and Mapping Section

Contents

Introduction

Constitutional and legislative basis

for payment

Remuneration Tribunal

Parliamentary base salary—a brief

history

1901–1973

Remuneration Tribunal

Reference salary—under the PEO

Classification

2009–2016

2016–

Percentage increases in the base

salary from 1996

Increases in the parliamentary base

salary compared with average wages from 1968

Introduction

Senators and members receive an annual allowance by way of

basic salary—$211,250 from 1 July 2019.[1] This research

paper explains the legislative basis, fixing and linking mechanisms for the

allowance. Adjustments to the base salary since 2000 and 1983 are provided in

Table 1 and Graph 1 respectively.

Constitutional

and legislative basis for payment

Section 48 of the Constitution

provides for the payment of Members of Parliament:

Until the Parliament otherwise provides, each senator and

each member of the House of Representatives shall receive an allowance of four

hundred pounds a year, to be reckoned from the day on which he takes his seat.

Since 1901, the Parliament has enacted legislation to define

the parliamentary base salary for the purposes of Section 48 of the Constitution.

Subsection 14(2) of the Parliamentary

Business Resources Act 2017 (PBR Act) provides that remuneration

must include a determination of an annual allowance payable for the purposes of

section 48 of the Constitution known as base salary.[2] Section 59

provides that salaries and allowances are to be paid out of the Consolidated

Revenue Fund.

Section 61 of the PBR Act allows the Governor-General

to make regulations necessary to give effect to the Act. The Parliamentary Business

Resources Regulations are now in force.

Remuneration Tribunal

The Remuneration

Tribunal is an independent statutory body established by the Remuneration

Tribunal Act 1973. The PBR Act allows

the Tribunal to inquire into and determine remuneration and allowances paid out

of consolidated revenue to senators and members.[3] In 1974 Parliament

disapproved the Tribunal’s determination increasing the base salary to $20,000

per annum. Since that time the Parliament has also modified determinations,

postponed increases and enacted reduced allowances previously determined by the

Tribunal as an example of wage restraint.[4]

The commencement of the Remuneration and Other

Legislation Amendment Act 2011 restored the power of the Remuneration

Tribunal to determine parliamentary remuneration. The legislation also removed

the power of the Parliament to disallow parliamentary remuneration

determinations made by the Tribunal.

Parliamentary

base salary—a brief history

1901–1973

At the Constitutional Convention at Sydney in 1891, Sir

Samuel Griffith said:

One of the first things to be done by the parliament of the

commonwealth in its first session would be to settle the salaries of ministers,

and a great number of other matters of that kind. We have, therefore, given

them power to deal with this subject. We did not think it necessary to make

this in any sense a payment of members bill. We lay down, however, the principle that they, are to receive

an annual allowance for their services, and we thought that it should start in

the first instance at £500.[5]

At the Adelaide Convention, however, the draft constitution

bill debated specified an amount of £400 and this was the annual allowance

subsequently enacted in the Constitution.[6]

In 1907 parliamentarians made themselves liable to the

payment of State income taxes.[7] Tax concessions

for electorate expenses were allowed from 1925.[8] In 1907 the

Parliament also enacted the Parliamentary Allowances Act 1907, raising

the base salary from £400 to £600.

Between 1901 and the establishment of the Remuneration

Tribunal in 1973, Parliament adjusted allowances following decisions of

executive government or as the result of recommendations from committees of

inquiry.[9] In 1971 Justice Kerr

noted that during this time there was ‘no fixed pattern of approach’ to the

timing and method of reviewing base salaries—a process that invariably

attracted criticism.[10] The Kerr Inquiry

suggested the establishment of a ‘Salaries Tribunal ... authorised by legislation

to review salaries and report at regular stated intervals.’

Kerr also wrote:

Nothing ... should prevent the Parliament or the Government

from rejecting recommendations or from taking action not in accordance with

what is recommended.[11]

Remuneration Tribunal

From its establishment in 1973, the Remuneration Tribunal,

using a range of evidence and indicators, determined the base salary with

reference to second division officers of the Commonwealth Public Service.[12] Adjustments were

then made by applying National Wage Case decisions. In 1979 the Government

legislated to remove the Tribunal’s determination that these adjustments be

automatic.[13]

In 1987 the Tribunal convened a conference for interested

parties to examine parliamentarians’ base salary.[14] An independent

review was consequently conducted for the Tribunal in 1988. The resulting

report recommended increases based on work value and community pay standards.

The review strongly recommended that there be no linkage between the base

salary and Australian Public Service (APS) salaries.[15] Increases

determined by the Tribunal at that time were

deferred.

With the Remuneration and

Allowances Act 1990,

the Government removed the Tribunal’s power to determine base salaries and

allowed a phased increase to the allowance over three years. The legislation

also provided a link with Senior Executive Service (SES) Band 1 salaries in the

APS—in contrast to the recommendation in the 1988 review. Adjustments to the

base salary were made by means of national wage case decisions and, from 1992,

agreements between the Government and public sector unions.

Legislation enacted in 1994 ensured that the base salary was

equivalent to the minimum APS SES Band 2 salary level. The then Workplace

Relations Act 1996 enabled SES salaries to be set through individual

Australian Workplace Agreements (AWAs), thereby removing the standard against

which the base salary was determined.

With the expiry of the final APS Enterprise Agreement at the

end of 1996, the mechanism by which adjustments were made to the base salary

ceased.

Legislative changes to the APS in 1999, among other matters,

amended the Remuneration and Allowances Act 1990 and the Remuneration

Tribunal Act 1973.

Reference

salary—under the PEO Classification

In Report 1999/01 the Tribunal recommended that the base

salary be linked to a reference salary under the Principal Executive Office

(PEO) Classification Structure.[16] The Government

accepted this recommendation and introduced the Remuneration

and Allowances Regulations 2005 to create the link. The Regulations provided

for the reference salary to be 100 per cent of the rate determined by the

Remuneration Tribunal for Band A of the PEO Classification.

The Remuneration Tribunal’s amending Determination

2008/10 increased Reference Salary A in the PEO Classification by 4.3 per

cent to $132,530 from 1 July 2008. Consequently, for the purposes of the base

salary in 2008–09, the Remuneration and Allowances Regulations reduced

Reference Salary A by 4.3 per cent.

On 26 May 2008, the Rudd Government introduced the Remuneration

and Allowances Amendment Regulations 2008

(No. 1) amending the Remuneration

and Allowances Regulations 2005 to freeze the base salary at $127,060 per

annum. Rather than 100 per cent of Reference Salary A, Regulation 5 described

the percentage as:

Regulation 5 Remuneration and allowances of Senators and

Members of the House of Representatives

(2) For the financial year commencing on 1 July 2008, and for each subsequent financial year:

(a) the percentage is the percentage of the reference salary

which, when applied to the reference salary, reduces the reference salary by

the amount (in whole dollars) by which the reference salary was increased by

the Remuneration Tribunal for the financial year commencing on 1 July 2008

For the purpose of calculating the base salary, Regulation 5

had the effect of reducing Reference Salary A in the PEO Classification by the

percentage necessary to arrive at the rate payable at 30 June 2008, that is,

$127,060.

On 20 June 2011 the Remuneration Tribunal released Determination 2011/11

Principal Executive Office (PEO) Classification Structure and Terms and

Conditions which set Reference Salary A at $146,380. On the basis described

above, that is Reference Salary A less $5,470, the parliamentary base salary

increased to $140,910 with effect from 1 July 2011.

Under the Remuneration

Tribunal Act 1973,

the Tribunal had wide scope to consider factors when reviewing the PEO

Classification. The Tribunal indicated that these factors included: key

economic indicators; other specific indicators such as the Wage Price Index;

salary outcomes in the public (and to a lesser degree) private sector; the

principles of wage determination and decisions of the Australian Industrial

Relations Commission.[17]

2009–2016

In 2009 an Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) report,

Administration of parliamentarians’ entitlements by the Department of

Finance and Deregulation, highlighted shortcomings in the management of

Members of Parliaments’ (MPs) entitlements.[18] In September 2009,

in response to the ANAO report, the Government set up a committee to review

parliamentary entitlements, chaired by former senior public servant, Barbara

Belcher.

In 2011 the Government accepted the recommendation of the Report

of the committee for the review of parliamentary

entitlements to restore the power of the Remuneration Tribunal to

determine parliamentary base salary.[19] The legislation,

the Remuneration and other Legislation Amendment Bill 2011, also removed the

power of the Parliament to disallow parliamentary remuneration determinations

made by the Tribunal. The Bill passed both Houses on 23 June 2011 and received

assent on 25 July 2011, commencing on 8 August 2011.

On 15 December 2011 the

Remuneration Tribunal issued its initial report on the work value assessment of

parliamentary remuneration.[20] The Tribunal also

issued a Statement outlining its recommendations and next steps.[21] The main

recommendations included:

on the basis of a work assessment of parliamentarians, that

parliamentary base salary should be set at $185,000

On 13 March 2012 the Tribunal issued a Determination setting

the base salary of $185,000 for MPs to take effect from 15 March 2012.[22]

On 19 June 2012 the Tribunal issued Determination 2012/15:

Members of Parliament – Base salary, entitlements and related matters which

increased MPs’ base salary by three per cent to $190,550 from 1 July 2012.[23]

On 18 June 2013, the Tribunal issued Determination 2013/13:

Members of Parliament – Base salary, additional salary for Parliamentary office

holders and related matters which increased the base salary by 2.4 per cent to $195,130

from 1 July 2013.[24]

In its 2014 Annual

review of Remuneration for Holders of Public Office, the Remuneration

Tribunal determined that there would be no annual adjustment to remuneration

for offices in its jurisdiction from 1 July 2014 for one year. This included

parliamentarians and office holders as well as other principal executive

offices.[25] Determination

2014/10 Members of Parliament–base salary, additional salary for

parliamentary office holders, and related matters gave effect to

this decision.[26]

In May 2015 the Tribunal deferred the determining of an

annual adjustment until later in the year.[27] On 9 December the

Tribunal determined that all offices in its jurisdiction would receive a two

per cent increase, effective 1 January 2016.[28]

2016–

Following the 2016 review

of an independent parliamentary entitlements system the Government

commenced a major overhaul of the remuneration and entitlements framework.

The Independent

Parliamentary Expenses Authority Act 2017 established the Independent

Parliamentary Expenses Authority

(IPEA) with effect from 1 July 2017. IPEA has the role of advising, monitoring,

reporting, auditing and processing functions relating to the work expenses,

travel expenses and travel allowances of members of parliament, certain travel

expenses of former members of parliament and the travel expenses and travel

allowances of staff employed under the Members of

Parliament (Staff) Act 1984.

The Parliamentary

Business Resources Act 2017 (PBR Act) and the Parliamentary

Business Resources (Consequential and

Transitional Provisions) Act 2017 (PBR (CTP) Act) received Royal

Assent on 19 May 2017 and commenced 1 January 2018. The PBR Act establishes

the new parliamentary work expenses framework. It is a principles-based

framework to cover parliamentarians' work expenses, requiring that the dominant

purpose be parliamentary business for any expense claimed and an overriding

principle of value-for-money for the Commonwealth.

The PBR Act and the PBR (CTP) Act replaced the

Parliamentary Entitlements Act 1990 and related legislation.

On 22 June 2017 the Remuneration Tribunal announced its

decision to increase remuneration by two per cent for public offices in its

jurisdiction, with effect from 1 July 2017. This included the base salary of

MPs. In its June 2017 Statement, 2017

Review of remuneration for holders of public office, the Remuneration Tribunal stated that this

‘represents an increase of 1.6 per cent per annum over the 18 months since the

last general increase decided by the Tribunal, effective from 1 January 2016’.[29]

Remuneration Tribunal Determination 2017/12 stated

that the base salary of an MP would increase from $199,040 to $203,030 per

annum from 1 July 2017.

On 23 June 2018 the Tribunal announced an increase of two

per cent for public offices in its jurisdiction, with effect from 1 July 2018.

The base salary of an MP increased to $207,100.[30]

On 23 June 2019 the Tribunal announced an increase of two

per cent for public offices in its jurisdiction, with effect from 1 July 2019.

The base salary of an MP increased to $211,250.[31]

In April 2020, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the

Government indicated it had made a submission to the Remuneration Tribunal

requesting no increase to the base salary for MPs in its annual review.[32]

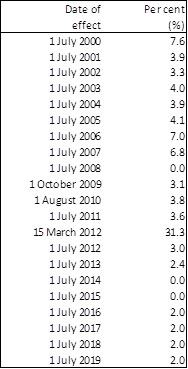

Table

1: Percentage increases in MP’s base salary, 2000–2019(a)

(a) Percentage

increases based on actual dollars.

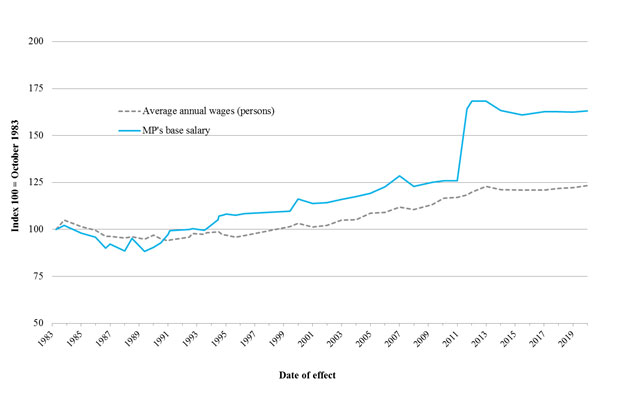

Increases to the parliamentary base

salary compared with average wages from the 1980s onwards

During the 1980s, the MPs’ base salary sat below inflation,

resulting in a decline in value in real terms. Wages at this time, however,

kept ahead of inflation and grew in real terms. By 1991, the base salary was

approximately twice that of average wages, leading to a series of catch up

increases throughout the 1990s.

Note the salary and wage series prior to 1983 is no longer

provided here due to inconsistencies in the way the earlier data series was

measured. The early series was reliant on full-time male wage earners and did

not entirely reflect women’s earnings. Base salary of MPs for these earlier

periods can however be found in the previous

version of this paper. The change to the selected series has also resulted

in updates to the base salary to average wages ratio (see far right column,

Table 2) with a notable widening of the gap.

In March 2012 MPs received a significant increase to their

base salary of 31.3 per cent, resulting in an allowance to average wage ratio

of 3.4. A subsequent increase in July of that year led to the ratio hitting its

highest level in over 35 years, at 3.5 (this timeframe covers the data series

for average earnings of all workers).

A freeze on MPs’ base salary during 2014 and 2015 had

minimal impact on the gap with average weekly earnings, reducing it by 0.1 of a

percentage point. Since 2014, the ratio has been stable at 3.3, with a slight

reduction expected due to the freeze in MP’s base pay requested by the

Government in April 2020.[33]

Table 2: MP’s

base salary compared with average wages, 1983–2020(a)

Annual

allowance

($ per

annum) |

Total

average wages (persons)(b)

($ per annum) |

Ratio -

allowance to

average

wages |

| Year |

Date of effect |

Current

prices |

Real prices

(Dec 2019)

dollars)(c) |

Current

prices |

Real prices

(Dec 2019)

dollars)(c) |

| 1983 |

6.10.1983 |

40,156 |

131,071 |

16,231 |

52,979 |

2.5 |

| 1984 |

1.5.1984 |

41,802 |

133,812 |

17,383 |

55,646 |

2.4 |

| 1985 |

1.7.1985 |

42,889 |

128,446 |

17,941 |

53,732 |

2.4 |

| 1986 |

1.7.1986 |

45,543 |

125,703 |

19,109 |

52,744 |

2.4 |

| 1987 |

10.3.1987 |

46,065 |

118,162 |

19,881 |

50,997 |

2.3 |

| 1987 |

1.7.1987 |

47,815 |

120,785 |

20,194 |

51,011 |

2.4 |

| 1988 |

1.7.1988 |

49,180 |

115,917 |

21,476 |

50,620 |

2.3 |

| 1989 |

1.1.1989 |

55,000 |

124,824 |

22,425 |

50,895 |

2.5 |

| 1989 |

16.11.1989 |

55,000 |

115,779 |

23,838 |

50,182 |

2.3 |

| 1990 |

1.7.1990 |

58,300 |

118,642 |

25,251 |

51,387 |

2.3 |

| 1991 |

1.1.1991 |

61,798 |

121,711 |

25,580 |

50,379 |

2.4 |

| 1991 |

1.7.1991 |

64,768 |

127,560 |

25,251 |

49,732 |

2.6 |

| 1991 |

15.8.1991 |

66,387 |

130,087 |

25,512 |

49,992 |

2.6 |

| 1992 |

17.12.1992 |

67,715 |

130,923 |

26,284 |

50,818 |

2.6 |

| 1993 |

11.3.1993 |

68,663 |

131,661 |

27,024 |

51,819 |

2.5 |

| 1994 |

1.1.1994 |

68,663 |

130,370 |

27,191 |

51,627 |

2.5 |

| 1994 |

10.3.1994 |

69,693 |

131,680 |

27,582 |

52,114 |

2.5 |

| 1994 |

15.12.1994 |

74,460 |

137,775 |

28,281 |

52,328 |

2.6 |

| 1995 |

12.1.1995 |

75,949 |

140,530 |

28,281 |

52,328 |

2.7 |

| 1995 |

6.4.1995 |

77,438 |

141,039 |

28,281 |

51,508 |

2.7 |

| 1995 |

13.7.1995 |

78,987 |

141,859 |

28,620 |

51,400 |

2.8 |

| 1996 |

7.3.1996 |

80,251 |

140,864 |

28,959 |

50,831 |

2.8 |

| 1996 |

17.10.1996 |

81,856 |

142,177 |

29,485 |

51,213 |

2.8 |

| 1999 |

7.12.1999 |

85,500 |

143,779 |

31,962 |

53,748 |

2.7 |

Table 2 (cont)

| Annual allowance ($ per

annum) |

Total

average wages (persons)(b)

($

per annum) |

Ratio -

allowance to

average

wages |

| Year |

Date of

effect |

Current

prices |

Real prices

(Dec 2019 dollars)(c) |

Current

prices |

Real prices

(Dec 2019 dollars)(c) |

| 2000 |

1.7.2000 |

92,000 |

152,285 |

33,046 |

54,701 |

2.8 |

| 2001 |

1.7.2001 |

95,600 |

149,110 |

34,428 |

53,699 |

2.8 |

| 2002 |

1.7.2002 |

98,800 |

149,877 |

35,653 |

54,085 |

2.8 |

| 2003 |

1.7.2003 |

102,760 |

151,917 |

37,614 |

55,607 |

2.7 |

| 2004 |

1.7.2004 |

106,770 |

153,929 |

38,657 |

55,731 |

2.8 |

| 2005 |

1.7.2005 |

111,150 |

156,364 |

40,888 |

57,521 |

2.7 |

| 2006 |

1.7.2006 |

118,950 |

160,908 |

42,739 |

57,815 |

2.8 |

| 2007 |

1.7.2007 |

127,060 |

168,351 |

44,762 |

59,309 |

2.8 |

| 2008 |

1.7.2008 |

127,060 |

161,183 |

46,144 |

58,536 |

2.8 |

| 2009 |

1.10.2009 |

131,040 |

163,906 |

47,896 |

59,908 |

2.7 |

| 2010 |

1.8.2010 |

136,040 |

165,009 |

50,946 |

61,795 |

2.7 |

| 2011 |

1.7.2011 |

140,910 |

165,058 |

52,933 |

62,004 |

2.7 |

| 2012 |

15.3.2012 |

185,000 |

215,185 |

53,897 |

62,691 |

3.4 |

| 2012 |

1.7.2012 |

190,550 |

220,537 |

54,914 |

63,556 |

3.5 |

| 2013 |

1.7.2013 |

195,130 |

220,565 |

57,615 |

65,125 |

3.4 |

| 2014 |

1.7.2014 |

195,130 |

214,109 |

58,553 |

64,248 |

3.3 |

| 2015 |

n/a |

195,130 |

210,922 |

59,278 |

64,075 |

3.3 |

| 2016 |

1.1.2016 |

199,040 |

213,362 |

59,737 |

64,035 |

3.3 |

| 2017 |

1.7.2017 |

203,030 |

213,117 |

61,473 |

64,527 |

3.3 |

| 2018 |

1.7.2018 |

207,100 |

212,965 |

62,954 |

64,737 |

3.3 |

| 2019 |

1.7.2019 |

211,250 |

213,826 |

64,544 |

65,331 |

3.3 |

| 2020d |

n/a |

211,250 |

211,250 |

65,540 |

65,540 |

3.2 |

(a) Wages growth to

Nov 2019 and published MPs’ base allowances to July 2019.

(b) Average

weekly wages annualised (then

adjusted to real prices).

(c) Current

prices adjusted for inflation using Consumer Price Index (CPI) to Dec 2019 prices (Parliamentary Library calculations).

(d) Anticipated

freeze of base salary at 2019 level.

Sources:

Graph 1: Base salary for members of

parliament and average weekly wages index—real terms

Notes

- Graph 1 provides data until April 2020, but the axis labels are

set to show every two years from Oct 1983.

- The previous graph published in this paper provided a longer time

series for MP’s base salary compared to average weekly wages (real terms), but

was predominantly based on full-time male wage earners. The data shown here has

been updated to reflect total persons average weekly earnings. This change has

resulted in a different starting point for the graph, which the index has been

updated to reflect.

Tables 1 and 2, Graph 1

and commentary on the MPs’ base salary and real wages provided by the Statistics and Mapping Section.

[1]. The choice of phrase to describe the allowance payable

under Section 48 of the Constitution is a difficult one. ‘Basic salary’

is commonly used in an informal sense and serves to distinguish it from

salaries paid to ministers and office-holders. The authors have chosen to use

‘parliamentary base salary’. Federal parliamentarians are also entitled to

other benefits and allowances described in legislation. For the previous

entitlements framework see C Madden and D McKeown, Parliamentary remuneration and entitlements: 2016

update, Research paper series 2015–16,

Parliamentary Library, 2016. For the current framework see C Madden and D

McKeown, 2019 Parliamentary remuneration and business

resources: a quick guide, Research paper series 2019–20, Parliamentary Library,

2020. All hyperlinks correct as at 4 May 2020.

[2]. Parliamentary Business Resources Act 2017.

[3]. Parliamentary Business Resources Act 2017, section 45.

[4]. Remuneration Tribunal, 1982

Review, The Tribunal, Canberra, 1982, pp. 18–21 and Report 1999/01, The Tribunal, 1999, pp. 1–5.

[5]. S Griffith, Official Report of the National Australasian Convention Debates, Sydney,

2 April 1891, p. 654.

[6]. Official Report of the National

Australasian Convention Debates,

First Session, Adelaide, 22nd March to 23rd April 1897, pp. 1032–34.

[7]. Commonwealth Salaries Act 1907, Act no 7 of 1907.

[8]. E Page, House of Representatives, Debates,

4 June 1947, p. 3355. An Electorate Expense Allowance, not subject to income

taxation, was paid from 1952.

[9]. Including: Report of the Committee of Enquiry into the

Salaries and Allowances of Members of the National Parliament (Nicholas

Report), 1952; Report of the Committee of Enquiry into the Salaries and

Allowances of Members of the Commonwealth Parliament (Richardson Report), 1955;

Report of the Committee of Enquiry into the Salaries and Allowances of Members

of the Commonwealth Parliament (Richardson Report), 1959; Salaries and

Allowances of Members of the Parliament of the Commonwealth: A Report of

Inquiry by Mr Justice Kerr, (Kerr Report), 1971.

[10]. Mr Justice Kerr, ibid., p. 12.

[11]. Ibid., p. 16.

[12]. With the enactment of the Public Service Reform Act 1984, the Second Division of the Commonwealth Public Service

was replaced by the SES. See Public Service

Reform Bill 1984,

Bills Digest, 72, 1984, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, p. 2.

[13]. Remuneration and Allowances Act 1979.

[14]. Remuneration Tribunal, 1987 Review, pp. 5–12.

[15]. Cullen Egan Dell, Report on the pay and

allowances for members

of parliament: prepared

for the Remuneration Tribunal, 1988, pp. 18–19.

[16]. The PEO classification structure provides a framework for the negotiation of the terms

and conditions of PEO employment.

[17]. Remuneration Tribunal, Explanatory Memorandum: Determination 2004/15 –

Principal Executive Office (PEO) Classification Structure Terms and Conditions.

WPI is a product of the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The Tribunal’s Report

1999/01 highlights some of the factors given consideration by the Tribunal

during earlier deliberations.

[18]. Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), Administration of parliamentarians’ entitlements by the

Department of Finance and Deregulation,

ANAO, 2009.

[19]. Report of the Committee

for the Review of Parliamentary Entitlements (the Belcher review),

April 2010, p. 12.

[20]. Remuneration Tribunal, Review of the Remuneration of Members of Parliament: Initial

report, 15 December 2011.

[21]. Remuneration Tribunal, Reports, Members of Parliament, Secretaries of

Departments, Specified Statutory Offices, Statement, 15 December 2011.

[22]. Remuneration Tribunal, Determination 2012/02: Members of Parliament—Base salary and related

matters, 12 March 2012.

[23]. Remuneration Tribunal, Determination 2012/15: Members of Parliament—Base salary, entitlements and related matters, 19 June 2012.

[24]. Remuneration Tribunal, Determination 2013/13: Members

of Parliament – Base salary, additional salary for Parliamentary office holders

and related matters, 18 June 2013, accessed 13 August 2018; Remuneration Tribunal,

Determination 2013/13 Members of Parliament – Salary statement of reasons,

June 2013.

[25]. Remuneration Tribunal, 2014 Review

of Remuneration for Holders of Public Office,

Statement, 12 May 2014.

[26]. Remuneration Tribunal, Determination 2014/10: Members of Parliament—Base salary, additional salary

for parliamentary office holders, and related matters, 14 May 2014.

[27]. Remuneration Tribunal, 2015 Review of Remuneration for

Holders of Public Office, Statement,

31 March 2015; Remuneration Tribunal, Determination 2015/06 Members of

Parliament – Base Salary, Additional Salary for Parliamentary Office Holders,

and Related Matters, Reasons for Determination, The Tribunal, 11 May

2015.

[28]. Remuneration Tribunal, Determination 2015/22, Members of Parliament–Base salary, additional salary of parliamentary

office holders and related matters, The Tribunal,

9 December 2015.

[29]. Remuneration Tribunal, 2017 Review

of remuneration for the holders

of public office,

Statement, The Tribunal, 22 June 2017.

[30]. Remuneration Tribunal, Determination 2017/23 Members of Parliament, as at 1 July 2018, incorporating amending Determination 2018/06 Members of Parliament, 25 June 2018.

[31]. Remuneration Tribunal, Remuneration Tribunal (Members of Parliament)

Determination 2019, The Tribunal, 21

June 2019.

[32]. M Cormann (Minister for Finance), Transcript of interview with Peter

Stefanovic: Sky News First Edition: 3 April 2020: coronavirus economic response, media release, 3 April 2020.

[33]

D McCulloch, ‘Mathias Cormann resisting pay cut for MPs’, aap, 9 April 2020.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.