Chapter 7

Permanent models of care

7.1

The committee also examined alternative long-term placement options

available for children and young people in out-of-home care, including:

-

permanent care orders;

-

other orders that transfer guardianship of the child to the

child's carers; and

-

adoption.

7.2

As discussed in Chapter 4, long-term stability is a significant factor

in determining positive outcomes for children and young people in out-of-home

care. The committee heard widespread support for measures to increase stability

for children and young people in out-of-home care.

7.3

Particular support was expressed for 'permanency' in out-of-home care

placements, particularly for those children unable to return to their families.

The committee found multiple definitions of 'permanency', and a range of views

on how this could be achieved, including forms of legal permanency.

7.4

This chapter examines the role of permanent care and adoption

arrangements within the statutory child protection system. Culturally

appropriate permanent care arrangements for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander children will be examined in Chapter 8.

Permanent care options

7.5

Although all jurisdictions acknowledged the importance of providing

stable out-of-home care placements, the committee heard that approaches to 'permanency'

are largely inconsistent. The National Children's Commissioner, Ms Megan

Mitchell highlighted that permanency planning models are in the process of

development:

I think our care and protection systems

have historically been somewhat remiss in looking at the long-term stability

and safety of the child. They generally respond to incidents, or they did in

the past. I do think the states and territories are trying to amend that and

enhance legislation and practice so that there is a focus on a permanent

pathway from the beginning. However, that is not as common as it should be.[1]

7.6

The concept of 'permanency' in child placements is often conflated with

legally permanent arrangements such as guardianship orders or adoption. Recent

reforms in NSW, Victoria and the Northern Territory have focussed on improving

'permanency' for children in care through introducing new pathways to legal

permanency:

-

NSW – introduced provisions to remove barriers to adoption by

carers and the introduction of a new long-term guardianship order;[2]

-

Victoria – introduced timelines to achieve reunification with

birth families, after which permanent alternative care options will be sought;[3]

and

-

Northern Territory – introduced a permanent care order that

transfers guardianship of children in care to the carer.[4]

7.7

However, a number of witnesses noted that 'permanency' can be achieved

through multiple types of care and does not exclusively refer to the removal of

children for placement in legally permanent arrangements.[5]

Ms Mitchell explained that:

Generally permanency can be achieved by supporting the birth

family to care for the child and provide stability for that child. It can mean

a guardianship order. It can mean the supervision of a family in the community

for a period of time or it can mean adoption. But basically all the research is

very clear that stability and proper attachment to carers in the early years is

critically important for a child's positive development.[6]

7.8

Similarly, Ms Noelle Hudson from the CREATE Foundation told the

committee that stability and permanency can be achieved in the existing types

of out-of-home care:

[S]tability can be achieved by having a minimisation of

placements, and it can be achieved by looking at better matching and involving

young people in that decision making up-front rather than placing someone very

quickly and then discovering afterwards that it is not working out and quickly

repeating that cycle over and over again.[7]

Permanency planning

7.9

According to a 2006 study by Professor Clare Tilbury from Griffith

University, permanency planning is 'the process of making long-term care

arrangements for children with families that offer lifetime relationships and a

sense of belonging' and has been a guiding principle in child protection since

the mid-1970s. A permanent placement is 'more than a long-term placement; it is

a placement that meets a child's social, emotional and physical needs'.[8]

7.10

Planning for a permanent placement may include family reunion and long‑term

care arrangements. Data collected by the committee from states and territories

indicates all jurisdictions attempt reunification of children with their

parents as a permanent option. However, this data indicates there is no

national consistency in the models used across jurisdictions for permanency

planning.[9]

7.11

For example, there is no nationally consistent legislation requiring

permanency planning to be considered as soon as a child enters the out-of-home

care system. The National Children's Commissioner, Ms Mitchell, advised that

legislative changes in the United States which focussed on permanency had

contributed to a 30 per cent decline in the number of children in care

between 1998 and 2012. Ms Mitchell suggested the focus on permanency creates a

'paradigm shift' in the perception of out-of-home care services:

I think what is interesting about the US experience is they

have put in legislation that foster care is a temporary experience and should

not happen for more than, say, two years. That does not mean that there are not

kids in foster care but they have significantly changed the paradigm such that

foster care be seen as a temporary solution while you take the child and put

them in a safe situation for a period of time and you work out what is going to

be the long-term solution for that child, whether that be going back to their family—and

you put the family [on] strict notice that that is what will be happening but

you support them to get through whatever it is they are struggling with—or it

might be going to another permanent solution either through a guardianship or a

kinship arrangement or an adoption arrangement.[10]

7.12

Witnesses identified a lack of research into permanency planning in

Australia and the effectiveness of individual models.[11]

A 2013 review of evidence for out‑of‑home care by the Parenting

Research Centre of the University of Melbourne noted that there is 'little or

no substantial research' on permanency planning in Australia.[12]

AIHW submitted that early scoping work has been undertaken to investigate the

feasibility of reporting on approaches to permanency across jurisdictions, but

that further development is required.[13]

7.13

The committee heard from a number of organisations about different

models of permanency planning currently implemented across jurisdictions. For

example, concurrent planning is a process of planning for alternative permanent

care options practiced by Mackillop Family Services and UnitingCare in Victoria

and was suggested as a model that could implemented across jurisdictions (see

Box 7.1).

Box 7.1 – Best practice – Concurrent planning

Concurrent permanency planning is a process of working towards a primary permanent plan, such as

family reunification, while developing at least one alternative permanency plan at the same time,

such as long-term foster care.

Concurrent planning was first developed as a placement option in North America in the 1970s and is

now used as a third stream of out-of-home care (with foster care and kinship care) in several

countries worldwide, including the UK.

A 2012 review of the UK Coram Concurrent Planning Program (established in 1999) found despite

children carrying multiple serious risks into placements, none of the 28 cases studied had broken

down.

Connections Uniting Care and MacKillop Family Services have developed a concurrent care

program of integrated carer recruitment, training and support called 'Breaking down the silos'. The

program is delivered in Victoria and aims to enhance and expand the existing continuum of care for

infants and toddlers under three years old residing in out of home care.

The process combines intensive parental support towards a primary goal of reunification, while also

planning for the possibility of the foster placement becoming a permanent care outcome, with the

carer being dually trained and accredited for both potential outcomes. The program is aimed at

children under 3 years of age who are unlikely to remain in the care of their birth parents and have

no suitable relative/kinship placement options.

Source: Connections

UnitingCare, Submission 10, pp 8 – 16.

7.14

Some witnesses expressed concern that family reunification attempts may

be undermined if not adequately resourced in concurrent planning models. The

Women's Legal Service of New South Wales suggested that 'serious consideration'

be given to:

...identifying strategies to avoid the risk that concurrent

planning may undermine attempts at reunification, particularly if services 'are

not adequately resourced to provide comprehensive or intensive services to

families'.[14]

7.15

Similarly, the Aboriginal Child, Family and Community Care State

Secretariat NSW (AbSec) expressed concern that:

...restoration measures that apply concurrent planning are

properly resourced, to help set up a child’s return safely home, as well as

ensuring an equitable placement system.[15]

7.16

Rather than concurrent planning, Barnardos Australia (Barnardos)

recommended that foster care be split into two streams: one for restoration

care that undertakes crisis work to reunite children with families through

short-term care, and one for long-term care where reunification with families

is unlikely. Barnardos delivers two differentiated models of permanency

planning aimed at stopping the 'drift of children' through the out-of-home care

system. These include:

-

Temporary Family Care program, which works intensively with younger

children (mainly under 12 years of age) during a crisis to help reunite the

child with their parents; and

-

Find-a-Family program, which offers permanent family care and

adoption to children aged up to 12 years old, and long-term carers for

adolescents.[16]

Permanent care orders / transfer of

guardianship arrangements

7.17

Most jurisdictions have mechanisms to allow long-term carers to assume

legal guardianship for children on long-term care and protection orders. These

arrangements are generally considered where children are subject to care and

protection orders until they are 18 years old, or for those children who have

no prospect of reuniting with their families. These arrangements may be called

'permanent care orders' or other guardianship orders. Unlike adoption orders,

permanent care orders do not change the legal status of the child, and they

expire when the child turns 18 or marries. An application may also be made to

revoke or amend these orders.[17]

7.18

In most cases, children under 'permanent care orders' or other

guardianship orders are no longer supervised by the relevant department. In

some cases, carers may still have access to financial and practical supports,

subject to their individual circumstances. Table 7.1 outlines the key

differences between permanent care orders/transfer of guardianship orders

across Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and the Northern Territory.[18]

Table 7.1 – Permanent care arrangements across selected jurisdictions

|

Jurisdiction

|

Type of order

|

Legal requirements

|

Available supports

|

Statistics

|

|

New South Wales

|

Permanent care order

|

Report on steps taken to support reunification

Consultation with child (where over 12 years)

Compliance with Aboriginal Child Placement Principle

|

Ongoing financial supports available (carer payment)

|

Orders for 2 000 children granted since introduction in October 2014

|

|

Victoria

|

Permanent care order

|

Stability and cultural plan prepared

Report on steps taken to support reunification

Compliance with Aboriginal Child Placement Principle

Recommendation from Aboriginal agency

|

Ongoing financial supports available (where recommended)

|

2013-14: 302 orders granted

Since 1992: 3 686 orders granted

|

|

Queensland

|

Long-term guardianship order

|

Significant work undertaken to support reunification

Meets child's emotional security and stability needs

|

No ongoing financial supports (carer payments cease)

|

2013-14: 1 380 children on long-term guardianship order

|

|

Tasmania

|

Long-term guardianship order

|

Recommendation from department

|

Ongoing financial supports available (carer payments)

|

Over 200 guardianship transfers

|

|

Northern Territory

|

Permanent care order

|

Order considered the best means of safeguarding the wellbeing of the

child

|

One-off $5000 payment (carer payments cease)

|

No data available.

|

|

Western Australia

|

Special guardianship order

|

Carer demonstrated suitability

Compliance with Aboriginal Child Placement Principle and Culturally

and Linguistically Diverse Placement Guidelines

|

Ongoing financial supports available (where recommended)

|

2013-14: 69 orders

|

|

South Australia

|

Other person guardianship

|

Carer demonstrated suitability

Compliance with Aboriginal Child Placement Principle

|

Ongoing financially supports available (where recommended)

|

2013-14: 111 orders

|

Source: State and territory governments, answers to questions on notice,

30 April 2015 (received May–June 2015).

National consistency of permanent

care arrangements

7.19

The requirements for legal permanent care arrangements and supports

available to carers vary across jurisdictions, particularly with regard to

ongoing financial supports.

7.20

A number of submitters expressed concern that reforms aimed at

permanency would disproportionately affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander families. Ms Laura Vines from the Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention

Legal Service (FVPLS) in Victoria, told the committee recent changes to time

limits for family reunification in Victoria:

...will disproportionately impact Aboriginal children and

families, who are statistically more likely to experience complex trauma, such

as family violence, that cannot be quickly resolved according to an abbreviated

time line. In addition, we are concerned that these legislative changes will

damage the care, cultural connection and wellbeing of Aboriginal children by

significantly reducing departmental accountability towards Aboriginal children

in care.[19]

7.21

The NSW peak body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities,

AbSec, expressed concern about the lack of supports and services available for

children placed in legally permanent arrangements:

The more services and supports that are withdrawn, such as

assistance with maintaining contact, cultural support, recreational activities

or other supports that help keep children and young people on track and

connected, the more risk of placement breakdown, mainly due to pressures on

children, their families and on carers.[20]

7.22

In particular, the committee heard concerns about the impact of the new

permanent care orders in the Northern Territory on Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander communities. Unlike the NSW and Victorian orders, the NT does not

require compliance with the Aboriginal Child Placement Principle

or consultation with Aboriginal child care agencies, and carers are not able to

access ongoing financial support.[21]

7.23

The North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency (NAAJA) and Northern

Territory Legal Aid Commission (NTLAC) provided the committee with their joint

submission to the Northern Territory Government on its permanent care

legislation. The submission contained concerns that the legislation did not

have sufficient safeguards to ensure that permanent care orders are made only

as a last resort and Aboriginal children are able to maintain their connection

with family and culture.[22]

Representatives from NAAJA and NTLAC told the committee these concerns and

recommendations were not considered in the final legislation.[23]

7.24

It was put to the committee that permanent care orders can be granted

without consultation with the child's family or community. Mr Paddy Gibson from

the Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning told the committee that:

there is no obligation on the department to actually serve

papers on the family. All they will need to do is send papers to the last known

address of the parents that are there. So people's children could be being

completely severed from them legally and they do not even know the matter is on

in court, let alone have representation.[24]

7.25

At the committee's Darwin hearing, the NT Department of Children and

Families (DCF) confirmed there was no requirement for non-Aboriginal carers to

ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in their care maintain

contact with their family:

When a permanent care order is evoked, formalised and

completed, the holder of the permanent care order is the parent—I need to say

that very clearly—so they will make the determinations about whether there is

contact. They are the parent; they get to make those decisions.[25]

Adoption

7.26

One of the most contentious permanent care options examined by the

committee was adoption. The committee heard both support and opposition to

encouraging adoption as an option for children in out-of-home care.

7.27

AIHW defines adoption as:

[A] legal process where rights and responsibilities are

transferred from a child’s parent(s) to their adoptive parent(s). When an

adoption order is granted, the legal relationship between the child and their

parent(s) is severed. The legal rights of the adopted child become the same as

they would be if the child had been born to the adoptive parent(s).[26]

7.28

The committee recognises the complex history of adoption in Australia,

particularly past practices of forced removal of children for adoption

highlighted in the committee's 2012 report on the Commonwealth Contribution

to Former Forced Adoption Policies and Practices. The committee

acknowledges the trauma and pain that past forced adoption policies and

practices caused to thousands of Australians.[27]

7.29

The committee particularly recognises the impact of adoption on the

Stolen Generations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The

committee acknowledges the conclusions of the 1997 Bringing Them Home report

that: 'adoption is contrary to Aboriginal custom and inter-racial adoption is

known to be contrary to the best interests of Aboriginal children in the great

majority of cases'.[28]

7.30

A number of submitters noted the devastating effect that adoption and

forced removals have had on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.[29]

The Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care (SNAICC) noted

in its submission:

...for reasons detailed by the Bringing them home

report, adoption is not an appropriate consideration for our children. In line

with the intent and processes set out by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Child Placement Principle, placements and permanency options must

support the maintenance of safe connections to family, community and culture

for our children, and should only be considered with careful consultation with

appropriate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community representatives.[30]

7.31

Barnardos, one of the strongest advocates for adoption of children from

care, told the committee that it did not support the formal adoption of

Aboriginal children:

We have had experience in that area, and we are persuaded by

our Aboriginal colleagues about the devastation that many people experienced in

[sic] by being alienated from their culture. At the present time that is

certainly our opinion. We subscribe to this. This is what our colleagues want.[31]

7.32

More culturally appropriate forms of permanent care for Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander children and young people are discussed in Chapter 8.

Definition of adoption

7.33

The key difference between adoption and guardianship is the severing of

legal rights between the child and parents. Ms Louise Voight from Barnardos

told the committee that adoption is more than just a care arrangement:

[A]doption alters identity for life. It is not a way of

caring for children during childhood. One of our judges here said it very well

when the argument was whether the carers who were in front of him should actually

have a guardianship order rather than an adoption order. He said, 'We are who

society thinks we are,' and it is important later when you apply for your

driving licence, when you get married. It is not a gesture in childhood, and I

think that really needs to be thought about.[32]

7.34

Unlike past practices, all jurisdictions now facilitate 'open adoptions'

whereby children may maintain contact with parents; however, the degree to

which this occurs varies across the jurisdictions.[33]

According to AIHW, since 1998 the proportion of local adoptions where birth

families and adoptive families have agreed to allow some form of contact or

information exchange has generally been above 80 per cent.[34]

Key statistics

7.35

In 2013–14, out of a total of 317 adoptions (including intercountry

adoptions), 89 adoptions were by known carers, such as foster carers. The

number of known carer adoptions has fluctuated since 1999 and has steadily

increased over the past decade. In 2013-14, the number of known carer adoptions

was the highest on record.[35]

Figure 7.1 outlines the rising number of known carer adoptions in

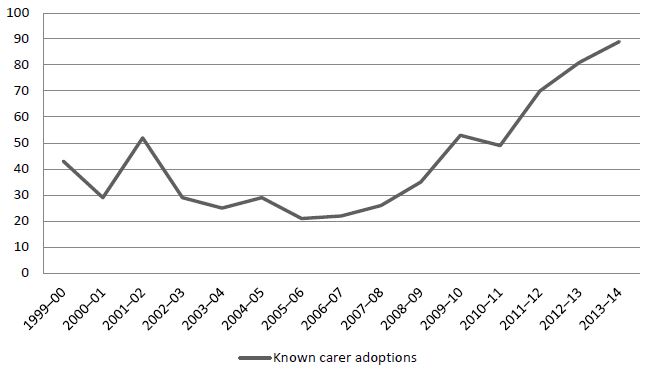

Australia since 1999.

Figure 7.1 – Number of known carer adoptions across jurisdictions 1999‑2000

to 2013-14

Source: AIHW, Adoptions

Australia 2013/14, Table A22.

7.36

According to AIHW, children adopted by known carers are generally older

than five years, with a large proportion aged more than 10 years. In 2013–14,

47.2 per cent of known carer adoptions were of children aged between five

and nine years old, and 41.6 per cent of children older than 10 years.[36]

7.37

AIHW reports that the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

children adopted each year is small. There have been 49 adoptions of Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander children in Australia since 2003–04. In 2013–14, seven

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander children were adopted. All these adoptions

were known child adoptions by adoptive parents who were either non-Indigenous

or whose Indigenous status was unknown.[37]

National consistency

7.38

In 2013-14, almost all known carer adoptions (84 of 89) were finalised

in NSW. This follows legislative changes as part of the Safe Home for Life

reforms that considers adoption as an option for children in out-of-home care

when they enter care.[38]

7.39

The NSW Government's A Safe Home for Life consultation paper

found widespread support for greater stability for children, but that there was

significant debate about the place of adoption. The report noted that:

Young people interviewed as part of the consultation process

(who had had experience of OOHC [out-of-home care] but not adoption) indicated

that they preferred the option of adoption over long-term foster care. However,

many private individuals and community members opposed adoption in any form

given the destructive consequences of the Stolen Generation and past forced

adoption policies and practices.[39]

7.40

Ms Maree Walk from the NSW Department of Families and Communities told

the committee that many of these concerns were based on the views of adults,

rather than a consideration of the needs of children:

[S]ome of our professional workers tend to be more focused on

the adults around the issue of adoption than possibly focused on the children.

And that is understandable given our history in Australia around adoption. It

will take some time. Particularly for very young children—children under five

or under three—it is about their long-term needs.[40]

7.41

Most jurisdictions emphasise keeping children with families where

possible and do not prioritise adoption; however, the committee heard several

jurisdictions were considering reviewing their approach to adoption. Mr Tony

Harrison, Chief Executive Officer of the South Australian Department of

Education told the committee that adoption is 'very topical in our state at the

moment'. South Australia has commenced a review of its Adoption Act (expected

to report in the second half of 2015) and the current state-based royal

commission is also investigating adoption as an option for children in

out-of-home care.[41]

7.42

The place of adoption in South Australia was also raised by the SA

Coroner's April 2015 report into the death of Chloe Valentine, a four-year-old

child who died as a result of injuries caused by being forced by her parents to

repeatedly ride a motorbike in 2012. The Coroner, Mr Mark Johns, recommended significant

changes to the child protection system in South Australia to protect children

from abuse and neglect, including removing barriers to adoption for children in

care.[42]

The SA Coroner's recommendation drew on a report by Dr Jeremy Sammut from the

Centre for Independent Studies (CIS) that argues for early statutory

intervention and permanent removal by means of adoption by suitable families.[43]

7.43

In Queensland, Mr Matthew Lupi, Executive Director of the Department of

Communities, Child Safety and Disability Services told the committee:

[W]e have the mechanisms to consider adoption and pathways to

consider adoption, and we are implementing practice improvements to try to

overcome any practice or ideological barriers that might be in place to routinely

considering it as a permanency option.[44]

7.44

Mr Tony Kemp, Deputy Secretary for the Department of Health and Human

Services in Tasmania, highlighted the need for approaches to adoption to be

discussed at the national level:

[T]he issue is about whether adoption becomes a part of the

child protection response. We [Department of Health and Human Service] do have

an adoption department here and we recently adopted a child from care, but that

does not happen very often...We are certainly keen to have a much larger

conversation at both the Commonwealth level and the state level about the role

of adoption in the child protection system.[45]

Adoption and out-of-home care

7.45

While most submitters agreed that adoption should have a place in the

continuum of care, the committee heard a range of views on what emphasis should

be placed on adoption and whether it should be prioritised over other forms of

care, including early intervention.[46]

The National Children's Commissioner, Ms Mitchell, suggested open adoption

practices could encourage a more positive assessment of the role of adoption:

[A]doption has had a chequered history and press in the

Australian context. We have in the past closed adoption. I think the advent of

open adoptions—where people know who their parents [are] and still have

connection if they want to with their family—actually provides another

opportunity to think about adoption in a more positive way. It really is case

by case.[47]

7.46

Ms Mitchell suggested in circumstances where the best interests of the

child would be served, adoptions should be made 'easier'.[48]

7.47

Barnardos, one of the largest care providers in NSW, recommended that the

adoption legislation in NSW should be implemented throughout Australia, with open

adoptions considered for all children committed to care until 18 years of age.

Barnardos argued 'children's wellbeing is not served well by staying in

long-term foster care because of the inherent instability of the system'.[49]

7.48

Barnardos told the committee that it has organised around 250 adoptions

in NSW and supports the stability adoption gives to children.[50]

Ms Louise Voight from Barnardos told the committee that although adoption may

not be suitable for all children, it should be considered as an option.[51]

7.49

However, most submitters and witnesses gave more cautious support to

adoption where it was in the child's best interest and considered as part of a

suite of options.[52]

Mr Tony Kemp, Deputy Secretary from the Tasmanian Department of Health and

Human Services, told the committee:

...adoption has a role to play in the suite of opportunities

and options we have. But we need to make sure that we do not fall into the same

traps that our predecessors have done, which is that it is all-in or nothing.

It has to be seen as part of a continuum and not seen as a standalone facility

for a cohort of care givers who have other issues that they need to resolve.[53]

7.50

The CREATE Foundation submitted that it was important to consider the

views of children and young people themselves in any decision about adoption,

noting that permanency can be achieved through existing types of care:

[P]ermanency and

living in a family environment will contribute to children and young people

being happy and maximising their life outcomes. This type of stability is

possible within the current kinship and foster care systems and it is not

essential for states and territories to prioritise adoption over foster care.

The circumstances of all children and young people in care are different and

decisions about placement should aim for stability but must be made on a

case-by-case basis, taking into account the views of children and young people

themselves and having regard to best practice principles to support all of the

people involved in the adoption.[54]

7.51

Ms Noelle Hudson from the CREATE Foundation also argued that children

and young people should be involved in the decision making process about

adoption and other permanent care arrangements:

[W]e need to allow that flexibility to meet the wishes and

desires of children and young people in care. So, if someone is very willing

and has a family arrangement and a care arrangement that is working out really

well, then, yes, that should happen. But it should always involve the young

person's decision.[55]

7.52

The committee heard concerns about adoption being singled out as a cost‑effective

means to reducing the numbers of children in care. Ms Mary McKinnon from Life

Without Barriers told the committee that:

[W]e have to keep engaging with the complexity of the

situation from the drivers in the community through poverty and all of that and

look for a breadth of response across the continuum from community development

in impoverished communities, placement prevention, improving the system and

better adoption. I think they all have to be on the table. I think the danger

is to select one.[56]

7.53

Mr Michael Geaney, from the Alliance for Children at Risk in Western

Australia, echoed concerns that adoption may be preferred as the 'cheaper'

option for governments:

The big fear...is that, because there are fiscal challenges in

the system, the adoption process is an easy way. 'Yep! 12 months and we're out

of this'—flick. It is off the books. The risk in that is that it is hidden and

then the cost goes somewhere else and so do all of the issues that are not

going to be resolved. There is plenty of evidence that adoption is not always a

successful strategy. I agree that there needs to be caution around this

approach. It is certainly not 'no' but rather to explore it and to make sure

that it is there for the right reasons—that is, in the child's best interests.[57]

7.54

A number of witnesses raised concerns about adoption being considered as

an alternative to other forms of existing care. Ms Judith Wilkinson, Chair of

the Children's Youth and Families Agency Association and State Manager for Key

Assets in WA, told the committee that they:

...we agree that there

has to be permanency planning and that we have to do it a lot better in this

state. There has to be certainty for children. There has to be the stopping of

drifting in care. The solution to that is not to jump straight into adoption.

The solution starts way back with preventing children coming into care in the

first place and then properly assessing their needs when they do come in and

putting them in the right place.[58]

7.55

The committee heard particular concerns about the conflation of the

concept of permanency with legal adoption. Life Without Barriers advised that

there is little evidence to suggest that the legal permanence created by

adoption was a significant factor in achieving actual permanence and stability

for the vast majority of children in out-of-home care.[59]

Life Without Barriers argued that:

we should focus on the needs of individual children and young

people in care and whether or not adoption, from a suite of alternatives, should

be considered. We consider that adoption is only likely to be suitable for a

small number of children relative to the overall numbers of children in out of

home care in Australia.[60]

7.56

Similarly, Ms Jessica Cocks of Family Inclusion Strategies Hunter (FISH)

told the committee that permanency depends on non-legal factors such as 'the

age of the child at adoption, the number of siblings in the family and the

needs of the child' more so than legal arrangements:

[W]e need to be really careful to distinguish between legal

permanence and actual permanence...adoptions do not necessarily equate to

permanence and that the factors that do lead to permanence are those that are

not necessarily legal.[61]

7.57

As noted earlier, the committee heard concerns that families who adopt

children from care would no longer have access to ongoing financial supports.[62]

Research from the US and UK provided to the committee by the Tasmanian

Department of Health and Human Services highlighted that permanence and

stability in adoption arrangements depend on the ongoing supports provided to

carers. A 2009 UK study of 130 children recommended for adoption found that 38

per cent of children failed to achieve a stable adoption. The study concluded that

support services for adoptive families to address the 'complex legacy of

deprivation and abuse' must be acknowledged and adequately resourced.[63]

Similarly, a 2015 study into outcomes for children adopted in the US

highlighted the need to 'tailor post-adoption services to specific types of

adoptive families which are at high risk for re-involvement in the child

welfare system' to improve outcomes for adopted children.[64]

Committee view

7.58

As discussed in Chapter 4, the committee recognises the importance of

permanency and stability in facilitating good outcomes for children and young

people in out-of-home care. The committee notes that there is a lack of

national data on permanency planning and permanent care placements for children

in out-of-home care.

7.59

The committee acknowledges the importance of a nationally consistent

approach to permanency planning across jurisdictions, including consideration

of different models that aim to improve stability for children and young people

in out-of-home care. However, the committee is concerned that the National

Standards do not include a measure to indicate how permanency planning is

applied across jurisdictions.

7.60

The committee recognises that 'permanency' can be achieved through a

range of different placement options, including stable relative/kinship or

foster care. In some cases, the committee acknowledges that legally permanent

placement options, including guardianship orders and adoption, may be appropriate

placement options for children and young people in long-term out-of-home care

placements. However, the committee notes that there is little evidence to

suggest legally permanent forms of care are effective in reducing the number of

children and young people in out-of-home care, and that the focus for child

protection authorities should remain on supporting families.

7.61

The committee is concerned that in some jurisdictions, children and

carers in adoption and guardianship order arrangements do not receive the same

level of financial and practical support as those in foster care and

relative/kinship care placements. If these placement options are to be utilised

more often, more resources need to be made available to ensure children and

carers continue to be supported.

7.62

The committee is also concerned about the lack of national consistency

on how and when permanent care orders may be made, particularly for Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander children maintaining contact with family. The

committee notes there is a wide discrepancy in the factors that must be taken

into account when making these orders across jurisdictions.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page